Achieving Quality Forest and Landscape Restoration in the Tropics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Introduction to the Case Studies

3. Forest and Landscape Restoration Case Studies

3.1. A Range of Potential Starting Points for Forest and Landscape Restoration

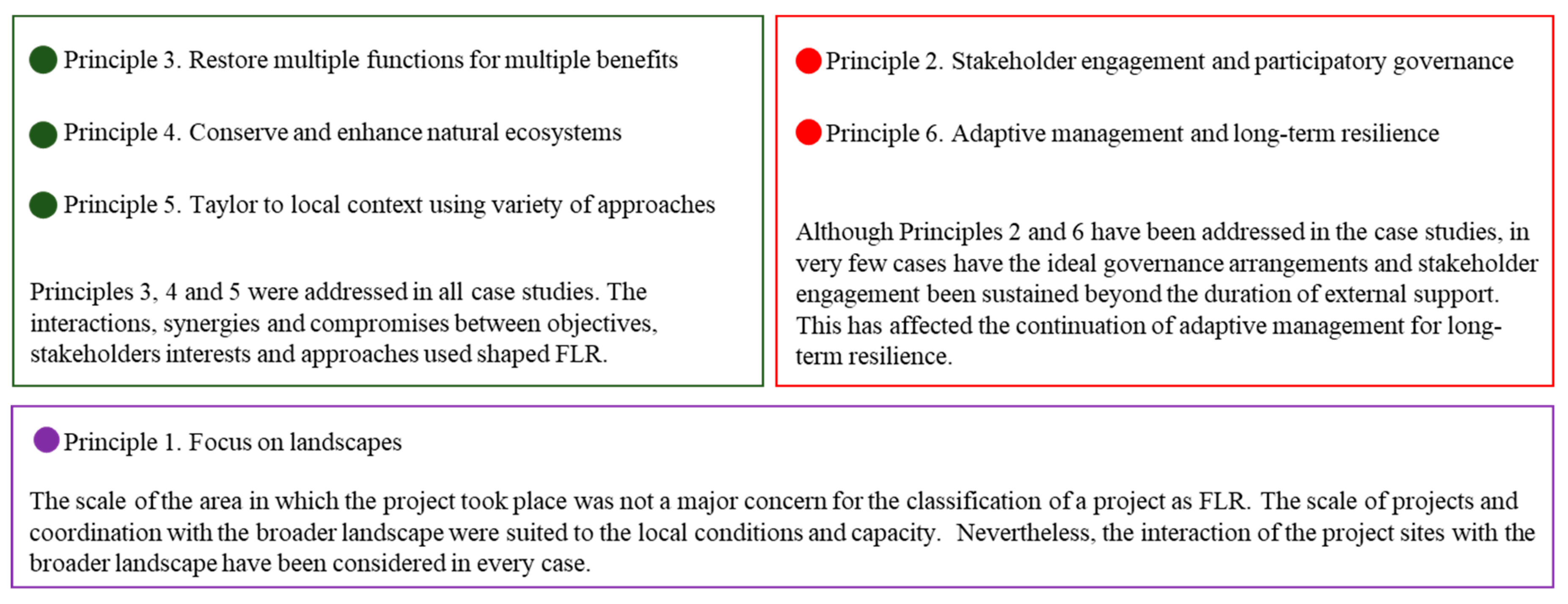

3.2. How Are the Principles of Forest and Landscape Restoration Incorporated into Practice?

3.3. The Benefits of Forest and Landscape Restoration

4. Main Challenges Encountered in Forest and Landscape Restoration

4.1. Limited Persistence of Gains

4.2. Limited Scaling up of Successful Initiatives

4.3. Limited Scope of FLR Project Monitoring, Reporting, and Learning

4.4. Need for Improved Governance in the Process

4.5. Technical Challenges

5. Prospects for Forest and Landscape Restoration

5.1. Innovative Business Models

5.2. FLR Implementation through Community Forestry

5.3. Linking to Other Synergetic Efforts

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brondizio, E.; Settele, J.; Díaz, S.; Ngo, H. Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; de Vries, W.; de Wit, C.A.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S.; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastin, J.-F.; Finegold, Y.; Garcia, C.; Mollicone, D.; Rezende, M.; Routh, D.; Zohner, C.M.; Crowther, T.W. The global tree restoration potential. Science 2019, 365, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griscom, B.W.; Adams, J.; Ellis, P.W.; Houghton, R.A.; Lomax, G.; Miteva, D.A.; Schlesinger, W.H.; Shoch, D.; Siikamaki, J.V.; Smith, P.; et al. Natural climate solutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 11645–11650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazdon, R.; Brancalion, P. Restoring forests as a means to many ends. Science 2019, 365, 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Shacham, E.; Walters, G.; Janzen, C.; Maginnis, S. Nature-Based Solutions to Address Global Societal Challenges; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 97. [Google Scholar]

- Chazdon, R.L. Second Growth: The Promise of Tropical Forest Regeneration in An Age of Deforestation; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stanturf, J.A.; Kleine, M.; Mansourian, S.; Parrotta, J.; Madsen, P.; Kant, P.; Burns, J.; Bolte, A. Implementing forest landscape restoration under the Bonn Challenge: A systematic approach. Ann. For. Sci. 2019, 76, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansourian, S.; Parrotta, J.; Balaji, P.; Bellwood-Howard, I.; Bhasme, S.; Bixler, R.P.; Boedhihartono, A.K.; Carmenta, R.; Jedd, T.; de Jong, W. Putting the pieces together: Integration for forest landscape restoration implementation. Land Degrad. Dev. 2020, 31, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremen, C.; Merenlender, A.M. Landscapes that work for biodiversity and people. Science 2018, 362, 6412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazdon, R.L.; Guariguata, M.R. Natural regeneration as a tool for large-scale forest restoration in the tropics: Prospects and challenges. Biotropica 2016, 48, 716–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukul, S.A.; Herbohn, J.; Firn, J. Co-benefits of biodiversity and carbon sequestration from regenerating secondary forests in the Philippine uplands: Implications for forest landscape restoration. Biotropica 2016, 48, 882–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWF; IUCN. Forests reborn: A workshop on forest restoration. In Proceedings of the WWF/IUCN International Workshop on Forest Restoration, Segovia, Spain, 3–5 July 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Laestadius, L.; Buckingham, K.; Maginnis, S.; Saint-Laurent, C. Before Bonn and beyond: The history and future of forest landscape restoration. Unasylva 2015, 66, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Besseau, P.; Graham, S.; Christophersen, T. Restoring Forests and Landscapes: The Key to A Sustainable Future; Global Partnership on Forest and Landscape Restoration: Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brancalion, P.H.S.; Chazdon, R.L. Beyond hectares: Four principles to guide reforestation in the context of tropical forest and landscape restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2017, 25, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maginnis, S.; Jackson, W. What is FLR and how does it differ from current approaches? In The Forest Landscape Restoration Handbook; Reitbergen-McCracken, J., Maginnis, S., Sarre, A., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2012; pp. 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, D.; Stanturf, J.; Madsen, P. What Is Forest Landscape Restoration? In Forest Landscape Restoration: Integrating Natural and Social Sciences; Stanturf, J., Lamb, D., Madsen, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabogal, C.; Besacier, C.; McGuire, D. Forest and landscape restoration: Concepts, approaches and challenges for implementation. Unasylva 2015, 66, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sayer, J.; Sunderland, T.; Ghazoul, J.; Pfund, J.-L.; Sheil, D.; Meijaard, E.; Venter, M.; Boedhihartono, A.K.; Day, M.; Garcia, C.; et al. Ten principles for a landscape approach to reconciling agriculture, conservation, and other competing land uses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 8349–8356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chazdon, R.L.; Laestadius, L. Forest and landscape restoration: Toward a shared vision and vocabulary. Am. J. Bot. 2016, 103, 1869–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN Environment. New UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration Offers Unparalleled Opportunity for Job Creation, Food Security and Addressing Climate Change; United Nations Environmental Program: Nairobi, Kenya, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sayer, J.; Boedhihartono, A.K. Integrated landscape approaches to forest restoration. In Forest Landscape Restoration: Integrated Approaches to Support Effective Implementation; Mansourian, S., Parrotta, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, J.; Van Vianen, J.; Deakin, E.L.; Barlow, J.; Sunderland, T. Integrated landscape approaches to managing social and environmental issues in the tropics: Learning from the past to guide the future. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2016, 22, 2540–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazdon, R.L.; Gutierrez, V.; Brancalion, P.; Laestadius, L.; Guariguata, M.R. Co-creating Conceptual and Working Frameworks for Implementating Forest and Landscape Restoration Based on Core Principles. Forests 2020, 11, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazdon, R.; Herbohn, J.; Mukul, S.; Gregorio, N.; Ota, L.; Harrison, R.; Durst, P.; Chaves, R.; Pasa, A.; Hallett, J.; et al. Manila Declaration on Forest and Landscape Restoration: Making it happen. Forests 2020, 11, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, S.; Chairuangsri, S.; Kuaraksa, C.; Sangkum, S.; Sinhaseni, K.; Shannon, D.; Nippanon, P.; Manohan, B. Collaboration and Conflict—Developing Forest Restoration Techniques for Northern Thailand’s Upper Watersheds Whilst Meeting the Needs of Science and Communities. Forests 2019, 10, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorio, N.; Herbohn, J.; Tripoli, R.; Pasa, A. A Local Initiative to Achieve Global Forest and Landscape Restoration Challenge—Lessons Learned from a Community-Based Forest Restoration Project in Biliran Province, Philippines. Forests 2020, 11, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.C.; Sabogal, C. Restoring Degraded Forest Land with Native Tree Species: The Experience of “Bosques Amazónicos” in Ucayali, Peru. Forests 2019, 10, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viani, R.A.G.; Bracale, H.; Taffarello, D. Lessons Learned from the Water Producer Project in the Atlantic Forest, Brazil. Forests 2019, 10, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldesemaet, Y.T. Economic contribution of communal land restoration to food security in Ethiopia: Can institutionalization help? In Enhancing Food Security through Forest Landscape Restoration: Lessons from Burkina Faso, Brazil, Guatemala, Viet Nam, Ghana, Ethiopia and the Philippines; Kumar, C., Begeladze, S., Calmon, M., Saint-Laurent, C., Eds.; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 144–173. [Google Scholar]

- Gregorio, N.O.; Herbohn, J.L.; Harrison, S.R.; Pasa, A.; Fernandez, J.; Tripoli, R.; Polinar, B. Evidence-based best practice community-based forest restoration in Biliran: Integrating food security and livelihood improvements into watershed rehabilitation in the Philippines. In Enhancing Food Security through Forest Landscape Restoration: Lessons from Burkina Faso, Brazil, Guatemala, Viet Nam, Ghana, Ethiopia and Philippines; Kumar, C., Begeladze, S., Calmon, M., Saint-Laurent, C., Eds.; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 177–217. [Google Scholar]

- Cuc, N. Mangrove forest restoration in northern Viet Nam. In Enhancing Food Security through Forest Landscape Restoration: Lessons from Burkina Faso, Brazil, Guatemala, Viet Nam, Ghana, Ethiopia and Philippines; Kumar, C., Begeladze, S., Calmon, M., Saint-Laurent, C., Eds.; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 106–121. [Google Scholar]

- Chazdon, R.L.; Wilson, S.J.; Brondizio, E.; Guariguata, M.R.; Herbohn, J. Key challenges for governing forest and landscape restoration across different contexts. Land Use Policy 2020, 104854, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansourian, S. Governance and forest landscape restoration: A framework to support decision-making. J. Nat. Conserv. 2017, 37, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maginnis, S.; Rietbergen-McCracken, J.; Sarre, A. The Forest Landscape Restoration Handbook; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) Toolbox; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ITTO. Guidelines for Forest Landscape Restoration in the Tropics; ITTO Policy Development Series; ITTO: Yokohama, Japan, 2020; Volume 23.

- Van Oosten, C. Restoring Landscapes—Governing Place: A Learning Approach to Forest Landscape Restoration. J. Sustain. For. 2013, 32, 659–676. [Google Scholar]

- Farina, A. The cultural landscape as a model for the integration of ecology and economics. BioScience 2000, 50, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, B. Participatory Exclusions, Community Forestry, and Gender: An Analysis for South Asia and a Conceptual Framework. World Dev. 2001, 29, 1623–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baynes, J.; Herbohn, J.; Smith, C.; Fisher, R.; Bray, D. Key factors which influence the success of community forestry in developing countries. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 35, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazdon, R.L.; Wilson, S.J.; Brondizio, E.; Guariguata, M.R.; Herbohn, J. Governance challenges for planning and implementing Forest and Landscape Restoration. Land Use Policy 2020, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Léopold, M.; Beckensteiner, J.; Kaltavara, J.; Raubani, J.; Caillon, S. Community-based management of near-shore fisheries in Vanuatu: What works? Mar. Policy 2013, 42, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damastuti, E.; de Groot, R. Effectiveness of community-based mangrove management for sustainable resource use and livelihood support: A case study of four villages in Central Java, Indonesia. Environ. Manag. 2017, 203, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nel, E.; Binns, T. Rural self-reliance strategies in South Africa: Community initiatives and external support in the former black homelands. J. Rural Stud. 2000, 16, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokorny, B.; Johnson, J. Community Forestry in the Amazon: The Unsolved Challenge of Forests and the Poor; ODI: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thapa, G.B. Changing Approaches to Mountain Watersheds Management in Mainland South and Southeast Asia. J. Environ. Manag. 2001, 27, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.J.; Coomes, O.T. ‘Crisis restoration’in post-frontier tropical environments: Replanting cloud forests in the Ecuadorian Andes. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 67, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Lassoie, J.P.; Wolf, S.A. Ecotourism development in China: Prospects for expanded roles for non-governmental organisations. J. Ecotourism 2011, 10, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, A.S.; Lyons-White, J.; Mills, M.M.; Knight, A.T. Learning from published project failures in conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 238, 108223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, K.; Ray, S.; Granizo, C.G.; Toh, L.; Stolle, F.; Zoveda, F.; Reytar, K.; Zamora, R.; Ndunda, P.; Landsberg, F.; et al. The Road to Restoration: A Guide to Identifying Priorities and Indicators for Monitoring Forest and Landscape Restoration, 1st ed.; WRI: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Morecroft, M.D.; Duffield, S.; Harley, M.; Pearce-Higgins, J.W.; Stevens, N.; Watts, O.; Whitaker, J. Measuring the success of climate change adaptation and mitigation in terrestrial ecosystems. Science 2019, 366, eaaw9256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langston, J.D.; Riggs, R.A.; Kastanya, A.; Sayer, J.; Margules, C.; Boedhihartono, A.K. Science Embedded in Local Forest Landscape Management Improves Benefit Flows to Society. Front. Forests Glob. Chang. 2019, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oosten, C.; Runhaar, H.; Arts, B. Capable to govern landscape restoration? Exploring landscape governance capabilities, based on literature and stakeholder perceptions. Land Use Policy 2019, 104020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraiappah, A.K.; Asah, S.T.; Brondizio, E.S.; Kosoy, N.; O’Farrell, P.J.; Prieur-Richard, A.-H.; Subramanian, S.M.; Takeuchi, K. Managing the mismatches to provide ecosystem services for human well-being: A conceptual framework for understanding the New Commons. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2014, 7, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.P.; Lawry, S.; Paudel, N.S.; McLain, R.; Adhikary, A.; Banjade, M.R. Operationalizing a Framework for Assessing the Enabling Environment for Community Forest Enterprises: A Case Study from Nepal. Small-Scale For. 2020, 19, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S.; Noack, F.; Angelsen, A. Climate, crops, and forests: A pan-tropical analysis of household income generation. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2018, 23, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukul, S.A.; Huq, S.; Herbohn, J.; Nishat, A.; Rahman, A.A.; Amin, R.; Ahmed, F.U. Rohingya refugees and the environment. Science 2019, 364, 138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tallis, H.; Huang, C.; Herbohn, J.L.; Holl, K.; Mukul, S.A.; Morshed, K. Steps Toward Forest Landscape Restoration in the Context of the Rohingya Influx: Creating Opportunities to Advance Environment, Humanitarian and Development Progress in Bangladesh; CGD Policy Paper; Center for Global Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Forest Management Bureau. Forest and Landscape Restoration Approach: Modified National Greening Program; Quezon City, Philippines, 2020; Unpublished.

- Duguma, L.A.; Nzyoka, J.; Okia, C.A.; Watson, C.A.; Ariani, C. Restocking Woody Biomass to Reduce Social and Environmental Pressures in Refugee-Hosting Landscapes: Perspectives from Northwest. Uganda; World Agroforestry: Nairobi, Kenya, 2019; Volume 298. [Google Scholar]

| Project Title Relevant References | Location Area, Time Frame | Project Objectives Main Interventions | Main Outcomes and Lessons Learnt |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Water Producer Project [31], this issue | Joanopolis and Nazare Paulista, Brazil 489 ha, 2007–2015 | Testing Payment for Environmental Services as a tool for FLR. Implementation of conservation, restoration, and improved agricultural and soil conservation practices. Promotion of biodiversity conservation and water quality improvement | The project was partially successful. Goals were attained to some degree, but the area for conservation and restoration was much below target. Not all the money available for payment for environmental services (PES) was used because the participation of landowners was far below expectations. These factors contributed to limited success: absence of local organisations leading the project, no long-term guarantee of continuity of the project, amount of paperwork for landowners’ participation, inflexible institutions funding the project, and low PES value. |

| Multi-function forest restoration and management of degraded forest areas in Cambodia | Kbal Toeuk and O Soam, Cambodia 50 ha, 2012–2015 | Rehabilitation of degraded forests with timber and non-timber forest products. Establishment of tree nurseries and demonstration plots, and provision of training to community | Some of the goals of the project were achieved, but seedling survival rates of native species were low. Community achieved improved tenurial rights, reducing illegal forest activities. Community support was crucial, women had a very active role in the implementation of several activities. Three years of support may not be enough for the 50 ha of restoration to be sustainable, further technical and financial support are needed. |

| FLR in the Miyun Watershed–livelihoods and landscape strategy and megacity watershed initiative | Miyun Reservoir Watershed, China 30,000 ha, started in 2008 | Watershed protection and livelihood improvement. Promotion of close-to-nature forest management practices, support for fuelwood needs, high-value livelihoods, and management support to increase capacity of farmers and cooperatives | The project had both success and failures. It was successful in restoring some critical areas, setting up demonstration community-based restoration models, and establishing new mechanisms to fund watershed protection. Nevertheless, the attraction of new funding and scaling up of the model remain limited. Adding to that, the sustainability of funding and leadership were an issue. |

| Integrated Food Security Project in Northern Ethiopia [32] | Amhara Region, Ethiopia 1996–2008 | Social mobilization, institutionalisation of beneficiaries and livelihood development as a means to restore degraded land, sustain outputs, and make use of assets from restoration | Restoration project was successful in improving local livelihoods through the increase in income from fodder. The institutionalisation of beneficiaries was crucial to ensure good governance and persistent success. Degraded lands were rehabilitated. Despite the potential for income from carbon credits, the scale of the project is too small and there are no national markets for carbon in Ethiopia. |

| Campo Verde Project by Bosques Amazonicos in Ucayali [30], this issue | Ucayali, Peru 2040 ha, 2008–ongoing | Reforestation and rehabilitation of degraded areas and promotion of biodiversity conservation through planting and assisted natural regeneration and development of capacity of surrounding communities. | The project met its objectives and the restoration model was replicated in the region. Carbon credits were marketed in a few occasions. but discontinued owing to the burden related to the prerequisites of the mechanism. Success was attributed, among other factors, to the use of local valuable species and knowledge, intermediate technology employed, simplicity of operations, and institutional alliances. To scale-up the model, there is the need to provide reliable and suitable financing, technical assistance, and quality seedlings or seeds as a credit to be paid with timber sales. |

| Pilot community-based forest restoration project in Biliran Province [29], this issue, [33] | Caibiran, Biliran, Philippines 26 ha, 2013–ongoing | Restore watersheds, improve livelihoods, and test best practices for restoration. Interventions included social preparation, forest nursery establishment, planting for production forest, protection forest and agroforestry, and provision of livelihoods | The project was successful in terms of tree and crop establishment and growth. Community members were able to benefit from food products in the early years of the project and there is potential for benefits from timber in the future. Human and social capitals improved as a result of capacity training and community organisation promoted by the project. Nevertheless, challenges remain. Seedling nursery was expected to be an additional livelihood opportunity, but the community has not completed the application for accreditation by the responsible agency. The community organisation did not apply the best practices used in the project in a consecutive project they obtained. |

| The Carood Watershed Project | Carood Watershed, Philippines 2015–2017 | Strengthen and sustain partnerships among stakeholders, improve ecological conditions of watershed, sustain healthy supply of water, create enterprises, increase preparedness and resilience to climate change, and promote good governance and efficient use of resources | Project was highly successful in meeting goals. The watershed has been under the management by the Carood Watershed Model Forest Management Council since 2003 and demonstration and training sites for protection and production exist. The most important method for restoration was assisted natural regeneration, combined with fire prevention, soil and water conservation, and provision of livelihoods. Sustained maintenance and protection are prioritized and comprised the largest portion of the budget. |

| Philippines Penablanca Sustainable Reforestation Project | Penablanca Protected Landscape and Seascape, Philippines 2943 ha, 2007–2013 | Promotion of sustainable forest conservation and of compatibility of multiple uses of forests (i.e., biodiversity protection, watershed management, carbon sequestration, other ecosystem services for local communities) | The project had several achievements regarding sustainable conservation and management for multiple purposes, including the establishment and management of several marketable fruits and a business plan for marketing. Nevertheless, the goals of the project were too ambitious, stakeholders had overly-high expectations and the community was unable to manage reforestation funds, despite long capacity building effort. |

| Developing forest restoration techniques for northern Thailand’s upper watersheds while meeting the needs of science and communities [28], this issue | Doi Suthep–Pui National Park, Thailand 32 ha, 1996–2013 | Each stakeholder group had their own goals. The research organisation wanted to find effective restoration techniques, the local communities aimed at strengthening their rights to remain on the land, and the national park’s goal was to reclaim encroached land and reforest to meet national targets. The interventions carried out were promoting reforestation through tree planting and assisted natural regeneration | Through the project, the framework species approach for restoration was developed and knowledge on local species and adequate management for restoration increased. The project led to the recovery of carbon dynamics and reduced community conflicts, as well as improved biodiversity, relationship among stakeholders, community security to remain on the land they currently occupy, and assistance sourcing by local communities. Despite all the effort and resources dedicated to the project, sustainability of FLR can never be guaranteed and gains can be easily lost when changing political and economic conditions fail to support restoration or prevent fires. |

| Demonstration of capacity building of forest restoration and sustainable forest management in Vietnam [34] | North Vietnam 2010–2012 | Management, restoration, and protection of mangroves and climate change mitigation at the community level. Establishment of forest restoration using best practices, promotion of participatory design for enrichment planting and income generation from non-timber forest product, monitoring activities, enhancing of local institutions and policies, and improving local capacity | Thousands of hectares of mangroves were rehabilitated, but ensuring persistence of the plantings is challenging. The form in which the project operated helped changing society attitude towards mangrove, leading local people to protect and restore mangroves. The program had a very long duration (1996–2016), but the three years of the project support to local communities were not long enough to ensure sustained action. Forest extension workers must be skilled to work with communities and ethnic groups. Social preparation and capacity building take time. Native species should be selected by communities with advice from foresters to ensure species-site matching. Land and forest tenure are critical to ensure protection by households. If community is market driven, there is the opportunity to create community enterprise |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ota, L.; Chazdon, R.L.; Herbohn, J.; Gregorio, N.; Mukul, S.A.; Wilson, S.J. Achieving Quality Forest and Landscape Restoration in the Tropics. Forests 2020, 11, 820. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11080820

Ota L, Chazdon RL, Herbohn J, Gregorio N, Mukul SA, Wilson SJ. Achieving Quality Forest and Landscape Restoration in the Tropics. Forests. 2020; 11(8):820. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11080820

Chicago/Turabian StyleOta, Liz, Robin L. Chazdon, John Herbohn, Nestor Gregorio, Sharif A. Mukul, and Sarah J. Wilson. 2020. "Achieving Quality Forest and Landscape Restoration in the Tropics" Forests 11, no. 8: 820. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11080820

APA StyleOta, L., Chazdon, R. L., Herbohn, J., Gregorio, N., Mukul, S. A., & Wilson, S. J. (2020). Achieving Quality Forest and Landscape Restoration in the Tropics. Forests, 11(8), 820. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11080820