Cross-Impact Analysis with Crowdsourcing for Constructing Consistent Scenarios

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

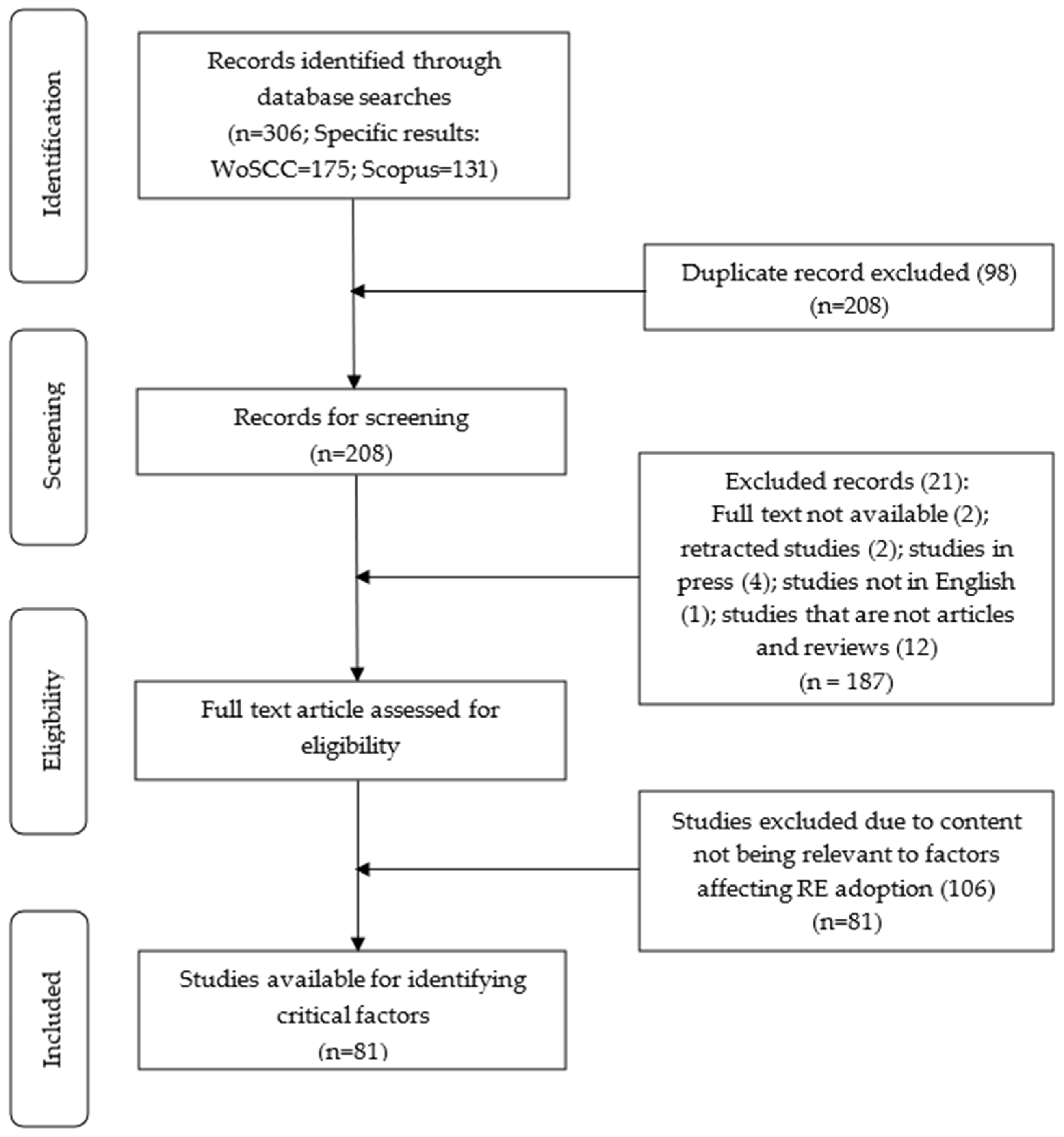

2.1. Materials Used

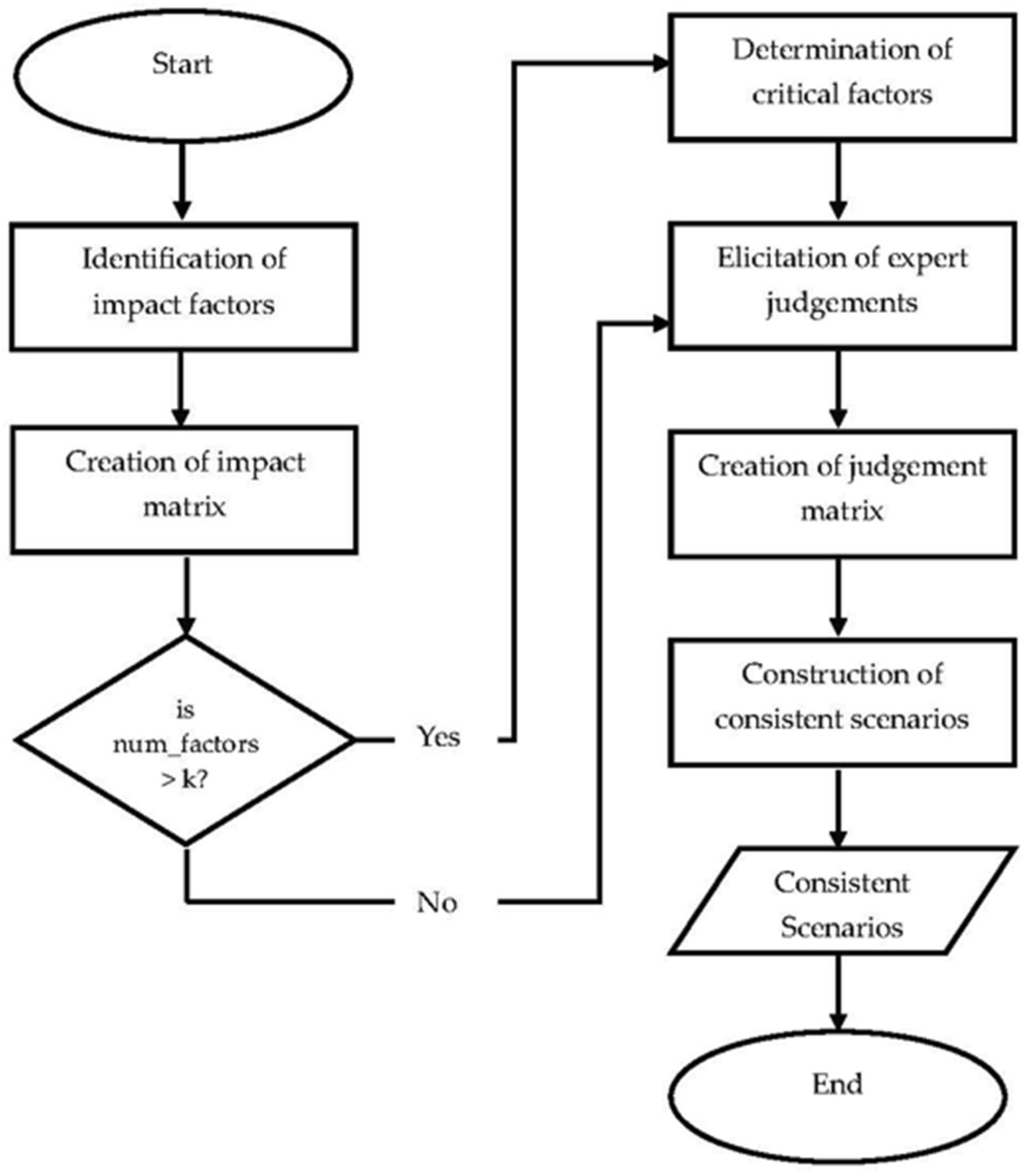

2.2. The Proposed CIACROWDS Method

2.2.1. Identification of Impact Factors

2.2.2. Creation of the Impact Matrix

2.2.3. Determination of Critical Factors

2.2.4. Elicitation of Expert Judgments

2.2.5. Creation of Judgment Matrix

2.2.6. Construction of Consistent Scenarios

3. Results

4. Conclusions

4.1. Discussion of Results

4.2. Limitations and Future Work

4.3. Ethical Considerations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADVIAN® | Advanced Impact Analysis |

| CIB | Cross-impact Balance |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

References

- Cordova-Pozo, K.; Rouwette, A.J.A.E. Types of Scenario Planning and Their Effectiveness: A Review of Reviews. Futures 2023, 149, 103153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiltunen, E. Scenarios: Process and Outcome. J. Futures Stud. 2009, 13, 151–152. [Google Scholar]

- Chermack, T.J.; Lynham, S.A.; Ruona, W.E. A Review of Scenario Planning Literature. Futures Res. Q. 2001, 17, 7–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, H.; Wiener, A.J. The Year 2000: A Framework for Speculation on the Next Thirty-Three Years; Political Science Quarterly; MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 1967; Volume 83. [Google Scholar]

- Schoemaker, P.J.H. When and How to Use Scenario Planning: A Heuristic Approach with Illustration. J. Forecast. 1991, 10, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoemaker, P.J.H. Multiple Scenario Development: Its Conceptual and Behavioral Foundation. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, E.A.; Schweizer, V.J. Objectivity and a Comparison of Methodological Scenario Approaches for Climate Change Research. Synthese 2014, 191, 2049–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimer-Jehle, W. Cross-Impact Balances: A System-Theoretical Approach to Cross-Impact Analysis. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2006, 73, 334–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, S.; Osmo, K.; Salminen, H. How Do We Explore Our Futures?: Methods of Futures Research; Finnish Society for Futures Study: Helsinki, Finland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kaviani, F.; Strengers, Y.; Dahlgren, K.; Korsmeyer, H. Automated and Absent: How People and Households Are Accounted for in Industry Energy Scenarios. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 102, 103191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linss, V.; Fried, A. The Advian® Classification—A New Classification Approach for the Rating of Impact Factors. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2010, 77, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielle, E.R.; Sharon, M.H.; Prochaska, J.J. Reaching Young Adult Smokers through the Internet: Comparison of Three Recruitment Mechanisms. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2010, 12, 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raford, N. Online Foresight Platforms: Evidence for Their Impact on Scenario Planning & Strategic Foresight. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2015, 97, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, G.; Chen, T.; Jentis, G.; Liu, Y.; McCulloh, C.; Harzman, A.; Huang, E.; Kalady, M.; Kim, P. Real-Time near Infrared Artificial Intelligence Using Scalable Non-Expert Crowdsourcing in Colorectal Surgery. NPJ Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankov, I.; Useche, A.F.; Meisel, J.D.; Montes, F.; Morais, L.M.; Friche, A.A.; Langellier, B.A.; Hovmand, P.; Sarmiento, O.L.; Hammond, R.A.; et al. From Causal Loop Diagrams to Future Scenarios: Using the Cross-Impact Balance Method to Augment Understanding of Urban Health in Latin America. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 282, 114157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Ilya, S.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012, 25, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inel, O.; Tommaso, C.; Aroyo, L. Crowdsourcing Salient Information from News and Tweets. In Proceedings of the The Tenth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’16), Portorož, Slovenia, 23–28 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kucherbaev, P.; Florian, D.; Stefano, T.; Marchese, M. Crowdsourcing Processes: A Survey of Approaches and Opportunities. IEEE Internet Comput. 2015, 20, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, M.; Marta, P.; Thomson, J.D. Creating Value through Crowdsourcing: The Antecedent Conditions. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Group Decision and Negotiation, Warsaw, Poland, 22–26 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Seeber, I.; Alexander, M.; Gert-Jan, D.V.; Ronald, M.; Weber, B. Convergence on Self-Generated Vs. Crowdsourced Ideas in Crisis Response: Comparing Social Exchange Processes and Satisfaction with Process. In Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Belfiglio, A.; Page, S.D.; Pettersson, S.; van Rijn, M.; Vellone, E.; Westland, H.; Freedland, K.E.; Lee, C.; Strömberg, A.; Wiebe, D.; et al. Lessons Learned from the Moment Study on How to Recruit and Retain a Target Population Online, across Borders, and with Automated Remote Data Collection. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0257440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Notten, P. Scenario Development: A Typology of Approaches. In Schooling for Tomorrow Think Scenarios, Rethink Education; Organization for Economic: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, R.C.; Oludayo, O.O.; Singh, A. Cimgen Method for Generating Cross Impact Matrix in Impact Factor Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Information Communications Technology and Society (ICTAS), Durban, South Africa, 11–12 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Weimer-Jehle, W. Properties of Cross-Impact Balance Analysis. arXiv 2009, arXiv:0912.5352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linss, V.; Fried, A. Advanced Impact Analysis: The Advian® Method-an Enhanced Approach for the Analysis of Impact Strengths with the Consideration of Indirect Relations. Dep. Innov. Res. Sustain. Resour. Manag. 2009, Preprint. [Google Scholar]

- Guertler, B.; Spinler, S. Supply Risk Interrelationships and the Derivation of Key Supply Risk Indicators. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2015, 92, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.C.; Oludayo, O.O.; Singh, A. Deriving Critical Success Factors for Implementation of Enterprise Resource Planning Systems in Higher Education Institution. Afr. J. Inf. Syst. 2018, 10, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kayser, V.; Shala, E. Scenario Development Using Web Mining for Outlining Technology Futures. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 156, 120086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.A.; Grace, S.; David, A.C.; George, D.D.; Forouzandeh, F. Twitter (X) in Medicine: Friend or Foe to the Field of Interventional Cardiology? J. Soc. Cardiovasc. Angiogr. Interv. 2023, 6, 101136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDermott, S.; Manuela, A.; Mary, F.; Gabhann, L.M. Cultivating Engagement in Research Using Social Media Networks to Recruit Participants for Health Related Research. J. Curr. Trends Nurs. Health Care 2020, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Weimer-Jehle, W. ScenarioWizard, Version 4.54; Computer software; Cross-Impact Consulting: Stuttgart, Germany, 2023. Available online: https://www.cross-impact.org/english/CIB_e_ScW.htm (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Kishita, Y.; Takuma, M.; Hidenori, N.; Aoki, K. Computer-Aided Scenario Design Using Participatory Backcasting: A Case Study of Sustainable Vision Creation in a Japanese City. Futures Foresight Sci. 2023, 5, e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishita, Y.; Keishiro, H.; Michinori, U.; Umeda, Y. Research Needs and Challenges Faced in Supporting Scenario Design in Sustainability Science: A Literature Review. Sustain. Sci. 2016, 11, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Joanne, E.M.; Patrick, M.B.; Isabelle, B.; Tammy, C.H.; Cynthia, D.M.; Larissa, S.; Jennifer, M.T.; Moher, D. Updating Guidance for Reporting Systematic Reviews: Development of the Prisma 2020 Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, T.J. Cross-Impact Method; American Council for the United Nations University: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, F.; Chen, J.; Gabriela, S.; Ranjeet, J.; Susie, R.W.; Hogeun, P.; Shao, C. Applications of Structural Equation Modeling (Sem) in Ecological Studies: An Updated Review. Ecol. Process. 2016, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. Mis Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrolhassani, M.H.; Mostafa, M.; Rahimisadegh, R. Key Factors in the Future of Oral and Dental Health in Iran Using Scenario Writing Approach. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurniawan, J.H.; Maria, A.; Laima, E.; Andreas, G.; Lazurko, A.; Nordemann, E.; Esther, S.; Sharma, A.; Siddhantakar, N.; Veit, K. Towards Participatory Cross-Impact Balance Analysis: Leveraging Morphological Analysis for Data Collection in Energy Transition Scenario Workshops. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 93, 102815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millett, S.M. Should Probabilities Be Used with Scenarios? J. Futures Stud. 2009, 13, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Tori, S.; Geert, T.B.; Keseru, I. Building Scenarios for Urban Mobility in 2030: The Combination of Cross-Impact Balance Analysis with Participatory Stakeholder Workshops. Futures 2023, 150, 103160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankov, I.; Andres, F.U.; Jose, D.M.; Felipe, M.; Lidia, M.M.; Amelia, A.F.; Brent, A.L.; Peter, H.; Olga, L.S.; Hammond, R.A. Using Cause-Effect Graphs to Elicit Expert Knowledge for Cross-Impact Balance Analysis. MethodsX 2021, 8, 101492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, R.; Nelson, R.R.; Wynne, W.C.; Land, L. The Delphi Method Research Strategy in Studies of Information Systems. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2015, 37, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmawan, I.; Caitlin, B.; Tabetha, A.B.; Christi, A.P.; Eder, M. The Role of Social Media in Enhancing Clinical Trial Recruitment: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishita, Y.; Yuji, M.; Shinichi, F.; Umeda, Y. Scenario Structuring Methodology for Computer-Aided Scenario Design: An Application to Envisioning Sustainable Futures. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 160, 120207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.; Sibona, C. Crowdsourcing Surveys: Alternative Approaches to Survey Collection. J. Inf. Syst. Appl. Res. 2017, 10, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Anguera, M.T.; Mariona, P.; Salvador, C.-M.; Sanduvete-Chaves, S. Indirect Observation in Everyday Contexts: Concepts and Methodological Guidelines within a Mixed Methods Framework. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdock, H.E.; Gibb, T.D.; Andre, J.L.; Sawin, A.; Brown, L.; Ranalder, U.; Collier, C.; Dent, B.; Epp, C.; Kumar, H.; et al. Renewables 2021-Global Status Report; REN21: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Diesendorf, M. Scenarios for the Rapid Phase-out of Fossil Fuels in Australia in the Absence of Co2 Removal. Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN DESA. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2024; UNDESA: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wijaya, D.I.; Kokchang, P. Factors Influencing Generation Z’s Pro-Environmental Behavior Towards Indonesia’s Energy Transition. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, S.K.; Sidhartha, H.; Prakash, O. Factors Influencing the Adoption of Renewable Energy in India: Supplementing Technology-Driven Drivers and Barriers with Sustainable Development Goals. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2024, 21, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worrell, J.L.; Di Gangi, P.M.; Bush, A.A. Exploring the use of the Delphi method in accounting information systems research. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2013, 14, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami-Naeini, P.; Agarwal, Y.; Cranor, L.F.; Hibshi, H. Ask the experts: What should be on an IoT privacy and security label? In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 18–20 May 2020; IEEE: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020; pp. 447–464. [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren, M.; Bandhold, H. Scenario Planning-Revised and Updated: The Link Between Future and Strategy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, P.N. Steps Towards Scenario Planning. Eng. Manag. J. 1998, 8, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, S.E. Common Region: A New Principle of Perceptual Grouping. Cogn. Psychol. 1992, 24, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chermack, T.J. Scenario Planning in Organizations: How to Create, Use, and Assess Scenarios; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, N. Using Twitter Data in Research: Guidance for Researchers and Ethics Reviewers. Retrieved May 28th. 2020. Available online: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/data-protection/sites/data-protection/files/using-twitter-research-v1.0.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Pozzar, R.; Marilyn, J.H.; Meghan, U.-B.; Alexi, A.W.; James, A.T.; Hong, F.; Daniel, A.G.; Berry, D.L. Threats of Bots and Other Bad Actors to Data Quality Following Research Participant Recruitment through Social Media: Cross-Sectional Questionnaire. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e23021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Inclusion Criteria | ID | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| IC1 | Articles published in the English language. | EC1 | Articles with no full text available. |

| IC2 | Articles that report certain specific information, such as path coefficients. | EC2 | Retracted articles. |

| IC3 | Articles related to certain specific projects or factors impacting on renewable energy adoption. | EC3 | Articles marked as “in press”. |

| EC4 | Duplicate records. | ||

| EC5 | Articles that are not available in the English language. | ||

| EC6 | Gray articles like reviews, newsletters, or conference proceedings. | ||

| EC7 | Articles that do not report on certain specific information, such as path coefficients. | ||

| EC8 | Articles that do not relate to certain specific projects or factors impacting renewable energy adoption. |

| Factor Code | Factor Name | Factor Code | Factor Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | Perceived performance expectancy | F19 | Perceived risk |

| F2 | Perceived ease of use | F20 | Moral obligations |

| F3 | Perceived self-efficacy | F21 | Access to electricity |

| F4 | Social influence | F22 | Personal innovativeness |

| F5 | Awareness | F23 | Environmental knowledge |

| F6 | Perceived cost value | F24 | Perceived authority support |

| F7 | Attitude | F25 | Government policy and propaganda |

| F8 | Geographic and environmental factors | F26 | Social media influence |

| F9 | Behavioral intention | F27 | Moral norm |

| F10 | Usage behavior | F28 | Reason for adoption |

| F11 | Infrastructure readiness | F29 | Socio-demographic factors |

| F12 | Financial support | F30 | Perceived compatibility |

| F13 | Facilitating conditions | F31 | Personal financial commitments |

| F14 | Hedonic motivation | F32 | Perceived relevance (usefulness) |

| F15 | Perceived environmental awareness | F33 | Trialability |

| F16 | Perceived system quality | F34 | Pro-environmental behavior |

| F17 | Perceived trust | F35 | Perceived community identity |

| F18 | Perceived satisfaction | F36 | Homeownership |

| Factor Code | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | F8 | F9 | F10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 0.000 | 0.698 | 0.820 | 0.620 | 0.640 | 0.900 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.840 | 0.000 |

| F2 | 0.520 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.610 | 0.400 | 0.319 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.700 | 0.000 |

| F3 | 0.310 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.370 | 0.446 | 0.380 | 0.400 | 0.000 | 0.660 | 0.408 |

| F4 | 0.610 | 0.610 | 0.370 | 0.000 | 0.390 | 0.390 | 0.596 | 0.000 | 0.705 | 0.363 |

| F5 | 0.905 | 0.400 | 0.000 | 0.390 | 0.000 | 0.370 | 0.517 | 0.000 | 0.900 | 0.000 |

| F6 | 0.377 | 0.319 | 0.380 | 0.431 | 0.370 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.840 | 0.000 |

| F7 | 0.530 | 0.000 | 0.400 | 0.400 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 |

| F8 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| F9 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.520 |

| F10 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.168 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Measure | Description |

|---|---|

| Relative direct active sum (RDAS) | The direct active sum of a factor is converted to a relative value out of 100. |

| Relative direct passive sum (RDPS) | The direct passive sum of a factor is converted to a relative value out of 100. |

| Relative indirect active sum (RIAS) | The indirect active sum of a factor is converted to a relative value out of 100. |

| Relative indirect active sum (RIPS) | The indirect passive sum of a factor is converted to a relative value out of 100. |

| Criticality (CRI) | The strength of the impact that a factor has on other factors, and the strength of impact that other factors have on the factor. Calculated as the geometric mean of the relative indirect active sum and the relative indirect passive sum. |

| Integration (INT) | A measure of the strength of interrelations that a factor has with other factors. Calculated as the arithmetic mean of the relative indirect active sum and the relative indirect passive sum. |

| Stability (STA) | A measure of the degree to which a factor stabilizes the system of factors. Calculated by subtracting the harmonic mean of the relative indirect active sum and the relative indirect passive sum from 100. |

| Precarious (PRE) | A measure of the degree to which a factor influences the system of factors. Calculated as the harmonic mean of criticality and the relative indirect active sum. |

| Driving (DRI) | A measure of the degree to which a factor can influence other factors without the presence of feedback loops. Calculated as the harmonic mean of 100 minus criticality and the relative indirect active sum. |

| Driven (DRE) | A measure of the degree to which a factor is influenced by the system of factors. Calculated as the harmonic mean of 100 minus criticality and the relative indirect passive sum. |

| RDAS | RDPS | RIAS | RIPS | CRI | INT | STA | PRE | DRI | DRE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 66.74 | 58.58 | 76.97 | 61.18 | 68.62 | 69.07 | 31.83 | 72.68 | 49.15 | 43.81 |

| F2 | 32.29 | 30.23 | 44.36 | 37.02 | 40.52 | 40.69 | 59.64 | 42.40 | 51.37 | 46.92 |

| F3 | 22.82 | 30.48 | 29.27 | 40.64 | 34.49 | 34.95 | 65.97 | 31.77 | 43.79 | 51.60 |

| F4 | 46.44 | 47.45 | 59.13 | 54.95 | 57.00 | 57.04 | 43.04 | 58.05 | 50.42 | 48.61 |

| F5 | 39.19 | 27.44 | 52.17 | 38.20 | 44.65 | 45.19 | 55.89 | 48.26 | 53.74 | 45.99 |

| F6 | 34.44 | 22.30 | 43.91 | 38.08 | 40.89 | 40.99 | 59.22 | 42.37 | 50.94 | 47.44 |

| F7 | 16.45 | 75.59 | 22.77 | 75.01 | 41.33 | 48.89 | 65.06 | 30.68 | 36.55 | 66.34 |

| F8 | 4.41 | 4.41 | 3.01 | 1.78 | 2.32 | 2.40 | 97.76 | 2.64 | 17.16 | 13.18 |

| F9 | 6.41 | 100.00 | 2.39 | 100.00 | 15.45 | 51.19 | 95.34 | 6.07 | 14.20 | 91.95 |

| F10 | 1.02 | 16.40 | 0.89 | 25.20 | 4.74 | 13.05 | 98.28 | 2.06 | 9.22 | 48.99 |

| F11 | 19.12 | 8.71 | 17.69 | 10.44 | 13.59 | 14.07 | 86.87 | 15.51 | 39.10 | 30.03 |

| F12 | 12.00 | 1.57 | 14.73 | 2.32 | 5.84 | 8.53 | 95.99 | 9.28 | 37.25 | 14.77 |

| F13 | 13.00 | 10.76 | 33.87 | 16.99 | 23.98 | 25.43 | 77.38 | 28.50 | 50.74 | 35.93 |

| F14 | 18.52 | 2.30 | 26.17 | 5.43 | 11.91 | 15.80 | 91.01 | 17.66 | 48.01 | 21.86 |

| F15 | 33.71 | 28.89 | 48.80 | 43.84 | 46.26 | 46.32 | 53.81 | 47.51 | 51.21 | 48.54 |

| F16 | 15.74 | 1.51 | 23.08 | 2.22 | 7.16 | 12.65 | 95.95 | 12.86 | 46.29 | 14.36 |

| F17 | 5.64 | 9.11 | 8.68 | 2.90 | 5.02 | 5.79 | 95.66 | 6.60 | 28.72 | 16.59 |

| F18 | 14.83 | 7.56 | 17.78 | 9.14 | 12.74 | 13.46 | 87.93 | 15.05 | 39.38 | 28.24 |

| F19 | 24.68 | 27.95 | 35.15 | 36.32 | 35.73 | 35.74 | 64.27 | 35.44 | 47.53 | 48.32 |

| F20 | 15.88 | 16.08 | 22.39 | 21.86 | 22.12 | 22.12 | 77.88 | 22.25 | 41.76 | 41.26 |

| F21 | 4.24 | 0.00 | 2.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.15 | 95.39 | 0.00 | 15.18 | 0.00 |

| F22 | 20.60 | 15.85 | 33.04 | 27.07 | 29.91 | 30.06 | 70.24 | 31.44 | 48.13 | 43.56 |

| F23 | 21.46 | 15.88 | 29.15 | 26.90 | 28.00 | 28.03 | 72.02 | 28.57 | 45.81 | 44.01 |

| F24 | 7.39 | 0.79 | 6.19 | 0.28 | 1.31 | 3.23 | 99.47 | 2.85 | 24.71 | 5.25 |

| F25 | 18.82 | 4.09 | 21.10 | 2.55 | 7.33 | 11.82 | 95.46 | 12.44 | 44.22 | 15.36 |

| F26 | 6.95 | 0.00 | 4.81 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.40 | 90.39 | 0.00 | 21.92 | 0.00 |

| F27 | 7.55 | 0.00 | 7.85 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.93 | 84.30 | 0.00 | 28.02 | 0.00 |

| F28 | 9.44 | 7.41 | 10.85 | 12.02 | 11.42 | 11.43 | 88.60 | 11.13 | 31.00 | 32.63 |

| F29 | 1.67 | 0.00 | 2.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.02 | 95.93 | 0.00 | 14.26 | 0.00 |

| F30 | 12.07 | 8.83 | 16.75 | 13.69 | 15.14 | 15.22 | 84.93 | 15.93 | 37.70 | 34.08 |

| F31 | 0.97 | 0.00 | 1.24 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.62 | 97.52 | 0.00 | 11.14 | 0.00 |

| F32 | 14.32 | 14.01 | 13.99 | 29.33 | 20.26 | 21.66 | 81.05 | 16.84 | 33.40 | 48.36 |

| F33 | 4.53 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 99.16 | 0.00 | 6.46 | 0.00 |

| F34 | 1.11 | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.49 | 98.04 | 0.00 | 9.89 | 0.00 |

| F35 | 0.00 | 1.74 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| F36 | 2.98 | 0.00 | 1.41 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.70 | 97.19 | 0.00 | 11.86 | 0.00 |

| Factor Code | Precarious | Driving | Factor Code | Precarious | Driving |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 72.676 | 49.146 | F19 | 35.439 | 47.529 |

| F2 | 42.398 | 51.366 | F20 | 22.253 | 41.755 |

| F3 | 31.769 | 43.787 | F21 | 0.000 | 15.179 |

| F4 | 58.055 | 50.422 | F22 | 31.435 | 48.125 |

| F5 | 48.263 | 53.741 | F23 | 28.572 | 45.812 |

| F6 | 42.369 | 50.945 | F24 | 2.851 | 24.706 |

| F7 | 30.677 | 36.552 | F25 | 12.437 | 44.223 |

| F8 | 2.642 | 17.160 | F26 | 0.000 | 21.925 |

| F9 | 6.071 | 14.204 | F27 | 0.000 | 28.020 |

| F10 | 2.058 | 9.222 | F28 | 11.128 | 30.997 |

| F11 | 15.508 | 39.102 | F29 | 0.000 | 14.262 |

| F12 | 9.279 | 37.246 | F30 | 15.927 | 37.704 |

| F13 | 28.500 | 50.738 | F31 | 0.000 | 11.142 |

| F14 | 17.657 | 48.010 | F32 | 16.835 | 33.403 |

| F15 | 47.513 | 51.215 | F33 | 0.000 | 6.463 |

| F16 | 12.857 | 46.293 | F34 | 0.000 | 9.888 |

| F17 | 6.599 | 28.717 | F35 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| F18 | 15.051 | 39.383 | F36 | 0.000 | 11.862 |

| Threshold | 37.605 | 49.173 | 37.605 | 49.173 |

| Factor State | F1 | F2 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F13 | F15 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | ||

| F1 | High | 0 | 0 | 1 | −1 | 2 | −2 | 2 | −2 | 2 | −2 | 2 | −2 | 1 | −1 |

| Low | 0 | 0 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | |

| F2 | High | 2 | −2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | −2 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 2 | −2 | 1 | −1 |

| Low | −1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| F4 | High | 1 | −1 | 2 | −2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | −2 | 1 | −1 | 2 | −2 | 2 | −2 |

| Low | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | |

| F5 | High | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 2 | −2 |

| Low | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | |

| F6 | High | 2 | −2 | 1 | −1 | 2 | −2 | 1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | −2 | 1 | −1 |

| Low | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | |

| F13 | High | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 2 | −2 | 1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | −2 |

| Low | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 1 | |

| F15 | High | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 2 | −2 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 0 | 0 |

| Low | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Scenario | Best-Case Scenario | Base-Case Scenario | Worst-Case Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Performance Expectancy | High | Low | Low |

| Perceived Ease of Use | High | Low | Low |

| Social Influence | High | Low | Low |

| Awareness | High | High | Low |

| Perceived Cost Value | High | High | Low |

| Facilitating Conditions | High | Low | Low |

| Perceived Environmental Awareness | High | High | Low |

| Scenario Property | Promote RE Adoption | Moderate RE adoption | Restrict RE Adoption |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Thompson, R.C.; Olugbara, O.O.; Singh, A. Cross-Impact Analysis with Crowdsourcing for Constructing Consistent Scenarios. Algorithms 2026, 19, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/a19010041

Thompson RC, Olugbara OO, Singh A. Cross-Impact Analysis with Crowdsourcing for Constructing Consistent Scenarios. Algorithms. 2026; 19(1):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/a19010041

Chicago/Turabian StyleThompson, Robyn C., Oludayo O. Olugbara, and Alveen Singh. 2026. "Cross-Impact Analysis with Crowdsourcing for Constructing Consistent Scenarios" Algorithms 19, no. 1: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/a19010041

APA StyleThompson, R. C., Olugbara, O. O., & Singh, A. (2026). Cross-Impact Analysis with Crowdsourcing for Constructing Consistent Scenarios. Algorithms, 19(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/a19010041