1. Introduction

Given the persistent occurrence of traffic accidents, traffic surveillance systems are a fundamental component of improving traffic flow management and ensuring road safety. Most of these accidents stem from drivers’ failure to observe speed limits or traffic rules, which invariably ends in disaster. Aside from directly harming victims, these events are also socially disruptive, as the traffic they create disrupts other road users’ movements and upsets their daily routines. These challenges necessitate an effective traffic monitoring system to enhance road safety by preventing accidents and traffic jams [

1,

2].

The remaining traffic violations continue to occur due to a lack of driver discipline and usually threaten public safety. Likewise, conventional surveillance systems have drawbacks in real-time detection and violation tracking [

3]. The major challenge facing conventional systems is their limited ability to detect and classify different vehicle classes in crowded, complex traffic scenes. This necessitates the development of more advanced, technology-driven solutions capable of operating in real time.

There are many opportunities to overcome such constraints with computer vision and AI (more precisely, deep learning-based object detection algorithms) [

4]. Deep learning techniques (Fast R-CNN [

5], YOLOv3 [

6], YOLOv4 [

7]) have been successfully used for traffic monitoring, as they automatically extract features to detect objects. Despite significant advances in this field, there are still performance limitations in detecting objects (including small ones) or cars in complex traffic scenarios, which are crucial for improving system performance. Solving these issues is essential to reducing accidents, improving traffic efficiency, and enabling vehicle manhunts, all of which will contribute to a safer and more vibrant transportation ecosystem [

8,

9].

We propose a novel adaptation and enhancement of the YOLOv3 algorithm, which we call YOLO-LIO (Light-Traffic Intercept and Observation), to address the above challenges. First, it filters out background-image noise, leaving the area captured by the video source clean. Then, the YOLO-LIO model is applied to identify the item’s location and class accurately. In addition, YOLO-LIO can estimate vehicle velocity and the number of detected vehicles. The system assists in accurately detecting vehicles and establishing effective traffic monitoring protocols using YOLO-LIO, which are essential for reducing traffic congestion and enabling efficient traffic management.

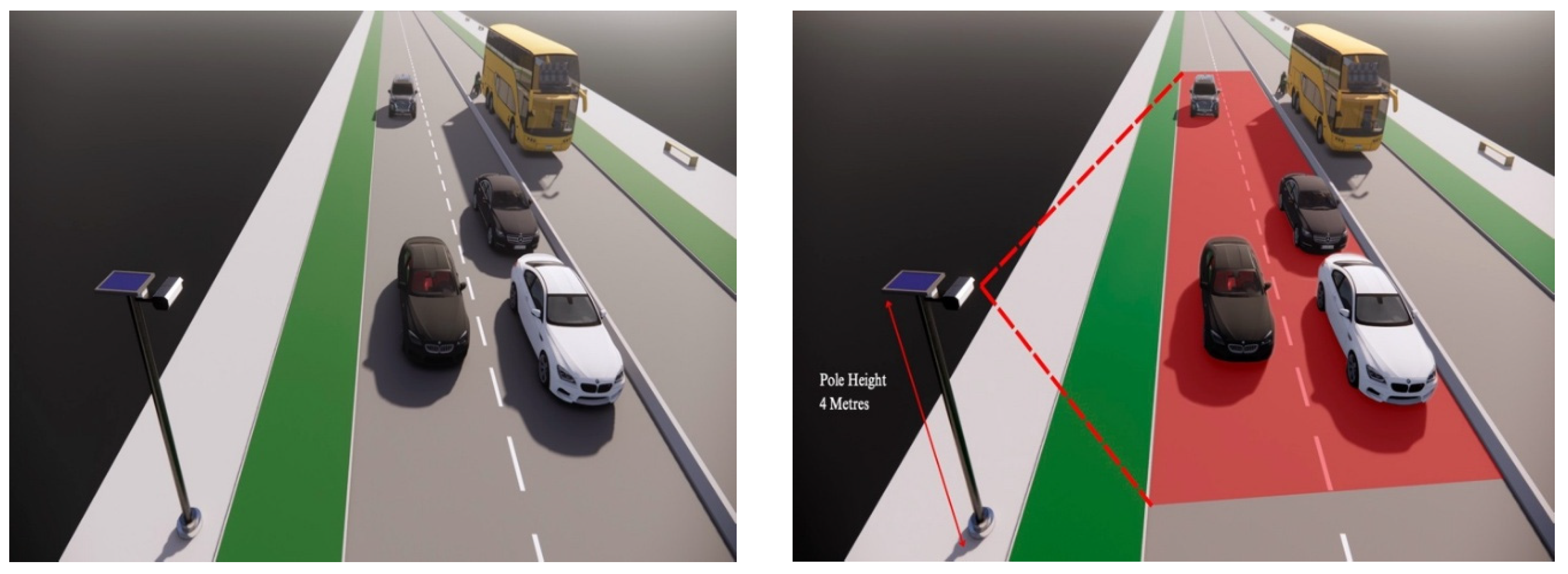

In this context,

Figure 1 depicts the location and design of a 3D model with the camera at a perfect height of 4 m. The Virtual Zone is configured to focus detection exclusively on vehicles traveling on the roadway, with the camera strategically positioned to ensure detection is confined within the designated Virtual Zone [

10]. This method dramatically increases system efficiency by reducing computational overhead and power consumption. This offers a highly efficient and low-overhead detection process.

This algorithm is significant in addressing the deficiencies of the current traffic detection approach and in establishing a consistent, easy-to-implement scheme for addressing complex traffic conditions in a practical time. This inherently makes real-time computing and car detection accuracy challenging, making YOLO-LIO a sophisticated, performance-proven traffic observer.

The main contributions of this work include:

Small-Object Detection Capability: Improved detection of small objects (distant vehicles) for better reliability.

Enhanced Multi-Scale Detailing: Complex architecture that accommodates object detection in vast ranges and variations, paving the way for this system to work fine in complicated settings.

Integration of Residual Blocks: Incorporating residual blocks aids feature extraction and helps prevent vanishing gradients during training, thereby improving overall detection accuracy.

Real-time Application Optimization: Achieves high processing speed, making it suitable for time-critical applications such as intelligent transportation and traffic management.

2. Related Work

Several recent studies have focused on improving the efficiency and robustness of object detection models, particularly for small and multi-scale objects that frequently appear in complex traffic environments. Cheng Xianbao et al. [

11] proposed a YOLOv3-based framework that replaces the conventional two-step down-sampling convolution with bilinear up-sampling and a dual-segmentation network, thereby preserving richer spatial features for both small and large objects. By incorporating a size-recognition module and residual connections into the fire module, their system successfully addressed the vanishing-gradient problem. It significantly improved small-object recognition accuracy by up to 20%, with notable gains in detection accuracy (from 82.4% to 88.5%), recall (from 84.6% to 91.3%), and average precision (from 95.5% to 97.3%). Similarly, Lingzhi Shen et al. [

12] presented enhancements designed for intelligent vehicle systems, introducing a K-means–GIoU anchor strategy, a dedicated branch for small-object detection, and a feature-map cropping module that reduces background interference. Their method improved mAP on the KITTI dataset by 2.86% over standard YOLOv3, achieving stronger performance on small-scale road targets while maintaining real-time processing.

More recent research has expanded these ideas by focusing on model efficiency and edge-oriented optimization, with lightweight YOLO variants designed for deployment on constrained hardware platforms such as the Jetson Nano, Raspberry Pi, and embedded ARM SoCs [

13,

14]. These works highlight the importance of architectural simplification, tensor compression, and multi-scale fusion to balance accuracy with real-time edge performance, an approach aligned with YOLO-LIO’s design philosophy. In parallel, modern Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) literature emphasizes system scalability and interoperability, particularly the integration of detection models into Big Data, cloud–edge pipelines, and I2X/V2X communication ecosystems [

15,

16,

17]. These studies show how detection models like YOLO-LIO can contribute to larger infrastructure systems that involve real-time data aggregation, traffic analytics, and cooperative vehicle–infrastructure communication. Incorporating these insights into YOLO-LIO further validates its relevance not only as a high-accuracy detection model but also as a scalable component suitable for emerging ITS and smart-city deployments.

2.1. YOLOv3 Architecture

YOLOv3 is a single-stage object detection algorithm that handles detection as a regression task, predicting class probabilities and bounding box coordinates for multiple objects directly without requiring a region proposal network like that used in R-CNN. This approach significantly enhances detection efficiency while maintaining high accuracy, even for diverse object types. YOLOv3’s feature extraction is driven by Dark-Net-53, which utilizes five residual blocks inspired by residual networks to address the vanishing gradient problem in deeper networks. These residual connections contribute to efficient feature learning, allowing the model to operate effectively in deep architectures [

18,

19,

20].

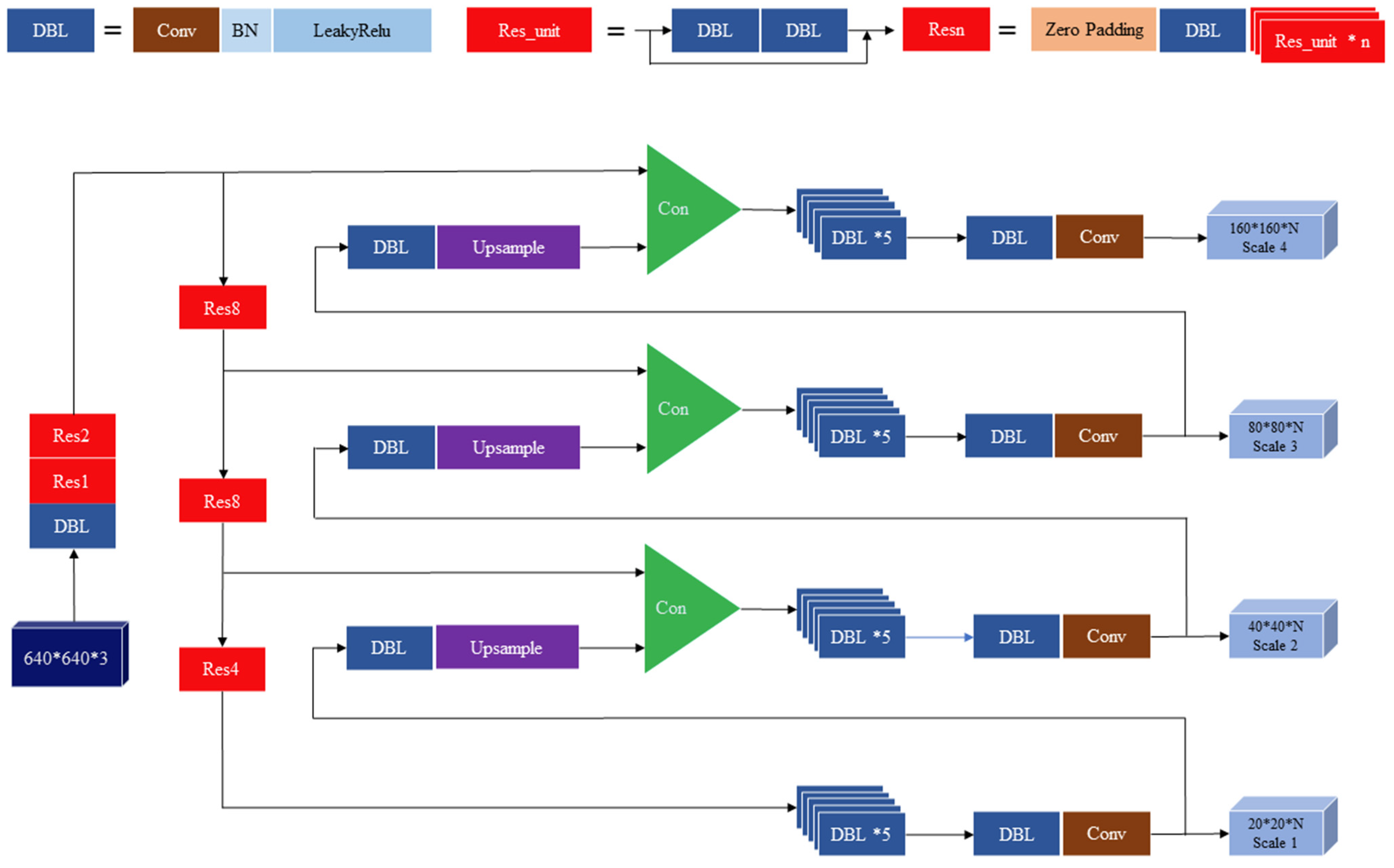

In YOLOv3, the input images are resized to 416 × 416, and deeper layers downsample the feature maps by 32×, while shallow layers preserve finer details. The proposed model incorporates a feature pyramid network (FPN) that allows down-sampling feature maps at different scales (8×, 16×, 32×) to increase its capacity to recognize small, medium, and large objects.

Figure 2 demonstrates how these components work together to achieve a balance of speed and accuracy in YOLOv3, including the DarkNet-53 backbone and multi-scale detection heads.

Figure 2 demonstrates how the network balances speed and accuracy by using a robust deep feature-extraction backbone (DarkNet-53) and multi-scale detection. The DBL block, which includes Conv, BN, and Leaky ReLU, is the basic building block for faster feature extraction and lower computational cost.

2.1.1. Feature Extraction

In YOLOv3, feature extraction is performed by the DarkNet-53 backbone, which begins by sending the input image

x through a DBL block, thus beginning the detection process as specified [

21]:

where

is the Leaky ReLU activation function. After this initial DBL block, the network uses Residual Blocks to learn deeper feature representations. A residual block is made of two DBL layers and has a residual connection that adds the input back to the output:

This kind of residual connection guarantees the efficient passage of gradients through several layers, hence solving the vanishing gradient problem faced by others in deeper networks. The feature extraction backbone of YOLOv3 employs three different deep residual blocks:

2.1.2. Multi-Scale Detection in YOLOv3

YOLOv3 utilizes multi-scale detection to detect objects of varying sizes. The network outputs object bounding boxes at up to three abstraction levels [

22]. It upsamples feature maps from deeper layers and concatenates them with shallower feature maps.

Scale 1 (Small Objects): The most miniature objects are detected with the most profound feature map:

The three different detection heads allow YOLOv3 to detect objects at different resolutions, helping it identify both small and large objects in the same image.

Each scale from YOLOv3 predicts the following three outputs:

The network is trained to return bounding box coordinates and class probabilities at each of these three scales, using anchor boxes to accommodate objects of different sizes and aspect ratios.

3. Method

3.1. Multi-Threaded Processing Framework

A multi-threading approach was adopted to run preprocessing tasks in parallel, thereby distributing the workload and improving system responsiveness under real-time conditions [

23]. To address common multi-threading drawbacks, such as complexity, debugging difficulty, shared-memory risks, and potential thread conflicts, the workflow was designed so that each thread operates on isolated data without accessing global variables or shared memory regions. This avoids race conditions and ensures thread stability, even on constrained edge hardware such as the Jetson Nano. The tasks were divided into independent, non-interacting units:

Thread 1 handles frame capture and Virtual Zone initialization.

Thread 2 performs preprocessing operations such as grayscale conversion, Laplacian variance analysis, and optional median filtering.

Threads 3 and 4 execute inference using YOLO-LIO on preprocessed frames.

Because each thread processes its own copy of the data and no inter-thread communication is required, the design remains lightweight, stable, and well-suited for embedded real-time deployment. This structured separation of tasks mitigates the typical disadvantages of multi-threading while still providing the intended performance benefits.

3.2. Virtual Zone—Based Region of Interest (ROI)

We define four lines to introduce a Virtual Zone limit detection of a camera in a quadrilateral area. This Virtual Zone also functions as a Region of Interest (ROI), which is a predefined area within the image where detection is intentionally focused. Using an ROI helps the system ignore irrelevant background regions and reduces computational workload, thereby improving YOLO-LIO’s overall performance and suitability for the objectives of this research.

In

Figure 3, the blue lines indicate the Virtual Zone, the region where vehicle detection is expected. Limiting the search space in this way ensures that detection is performed only within the relevant portion of the frame [

24,

25], making the process more efficient. The edges of the quadrilateral that define the Virtual Zone are represented as a set of four coordinate points:

A vehicle must be inside this blue area to be detected. This approach reduces irrelevant detections and enhances YOLO-LIO’s performance by enabling more accurate vehicle tracking and speed estimation within the designated operational zone.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the Virtual Zone (blue quadrilateral) defining the region of interest (ROI) for vehicle detection, within which YOLO-LIO performs localization, tracking, and speed estimation while excluding irrelevant background areas.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the Virtual Zone (blue quadrilateral) defining the region of interest (ROI) for vehicle detection, within which YOLO-LIO performs localization, tracking, and speed estimation while excluding irrelevant background areas.

3.3. Image Preprocessing Pipeline

The grayscale conversion formula used in the manuscript is based on the luminance model defined by the NTSC (National Television System Committee) and later adopted in the ITU-R BT.601 standard [

26]. These coefficients, 0.299 for red, 0.587 for green, and 0.114 for blue, are not arbitrary; they were empirically derived from studies of human visual perception. Specifically, the human eye is significantly more sensitive to green light, moderately sensitive to red light, and least sensitive to blue light [

27]. As a result, green contributes the highest weight in perceived brightness, followed by red and blue. The weighted sum formula:

Therefore reflects the proper physiological response of human photoreceptors and produces grayscale images that preserve visual brightness in a perceptually accurate way.

The Laplacian Variance Method quantifies the degree of intensity change within an image by measuring the statistical variance of its Laplacian response, which reflects the presence of edges and fine details [

28,

29]. A high variance indicates strong pixel-intensity fluctuations, corresponding to sharp, well-focused images, whereas a low variance suggests smooth transitions and potential blurriness. The Laplacian variance

is defined as:

where:

represents the variance of the Laplacian values.

are the Laplacian values at pixel .

is the mean of the Laplacian values across the image.

is the total number of pixels in the image.

It is crucial to distinguish Laplacian variance from the Mean Squared Error (MSE). Variance measures the spread of Laplacian responses around their mean, thereby indicating image sharpness, whereas MSE measures the squared difference between predicted and target values in regression tasks. In this study, Laplacian variance is used exclusively as an image-quality assessment metric during preprocessing and is not related to the MSE formulations commonly used in neural-network training. This clarification ensures consistent terminology and avoids conceptual overlap with unrelated loss-function definitions in prior literature.

The Median Filter Method is a non-linear digital filtering technique that removes noise from images or signals [

30]. It works by moving a window (or kernel) across the image, replacing the center pixel with the median of all the pixels within the window. The window size is typically a square of an odd number of pixels. The equation for the median filter can be expressed as follows:

where:

is the output (filtered) image at position .

are the pixel values in the neighborhood of the pixel at .

denotes the median value of the set of pixel values in the window centered at .

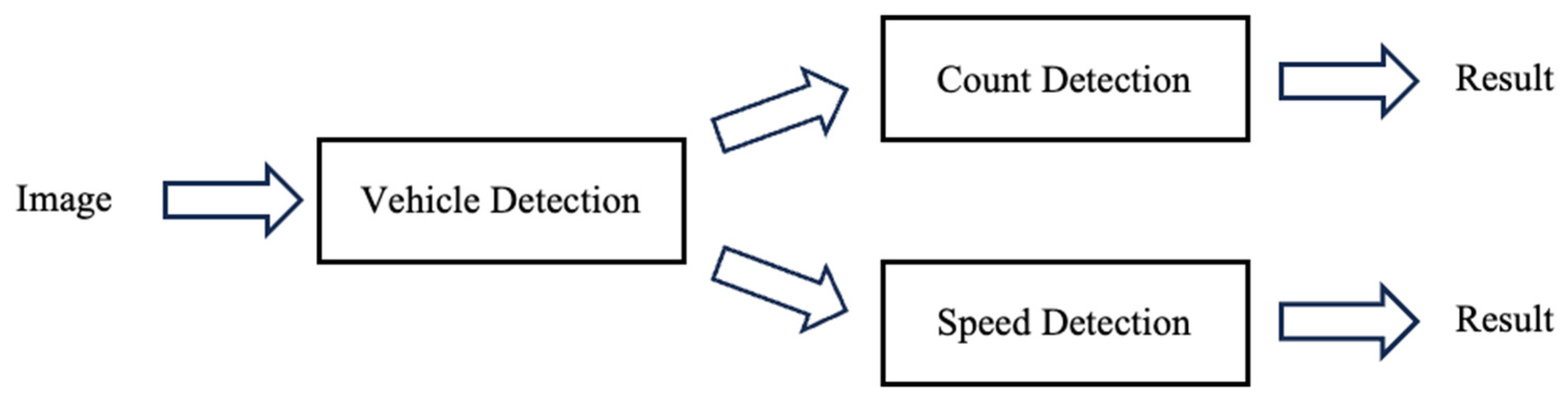

3.4. Vehicle Detection Framework

Vehicle detection involves identifying and locating vehicles within images or video frames. In computer vision and artificial intelligence, this task typically relies on algorithms and machine learning models to analyze visual data and determine the presence and position of vehicles, as well as additional information when needed [

31]. Real-time vehicle detection enables traffic authorities to monitor traffic flow, identify congestion patterns, and optimize traffic control systems. The overall system framework is illustrated in

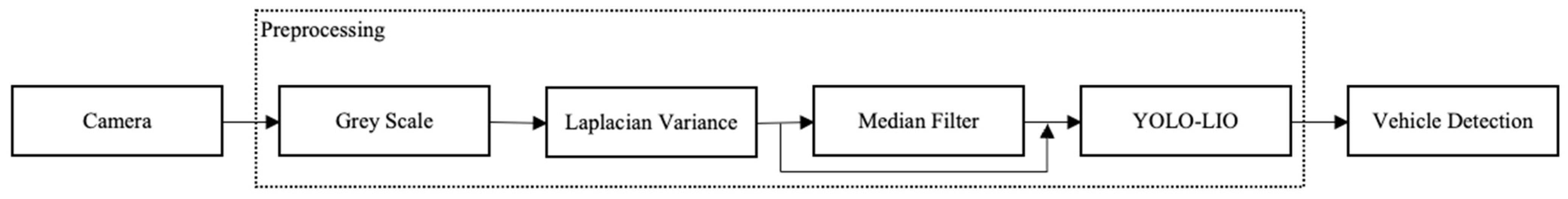

Figure 4.

Before applying the framework shown in

Figure 4, a multi-threading strategy assigns specific tasks to individual CPU cores, ensuring effective utilization of hardware resources.

Preprocessing begins by converting the input image to greyscale to reduce data complexity and accelerate subsequent detection stages. Next, the Laplacian Variance method is applied to evaluate image sharpness. When the image is low-quality, a median filter is applied to reduce noise and improve visual clarity; otherwise, this stage is skipped to avoid unnecessary computation. This selective preprocessing step improves detection accuracy while maintaining processing efficiency.

Following preprocessing, the YOLO-LIO detection framework is used to detect and classify objects into four predefined classes: motorcycle, car, bus, and truck. YOLO-LIO outputs bounding boxes for each identified object, and the final detection pipeline balances accuracy and computational speed, making it suitable for real-time deployment.

The camera in our setup is mounted at a height of 4 m. This perspective makes vehicles appear relatively small within the frame, which aligns with the design of YOLO-LIO’s multi-scale detection architecture and contributes to more efficient and stable detection performance.

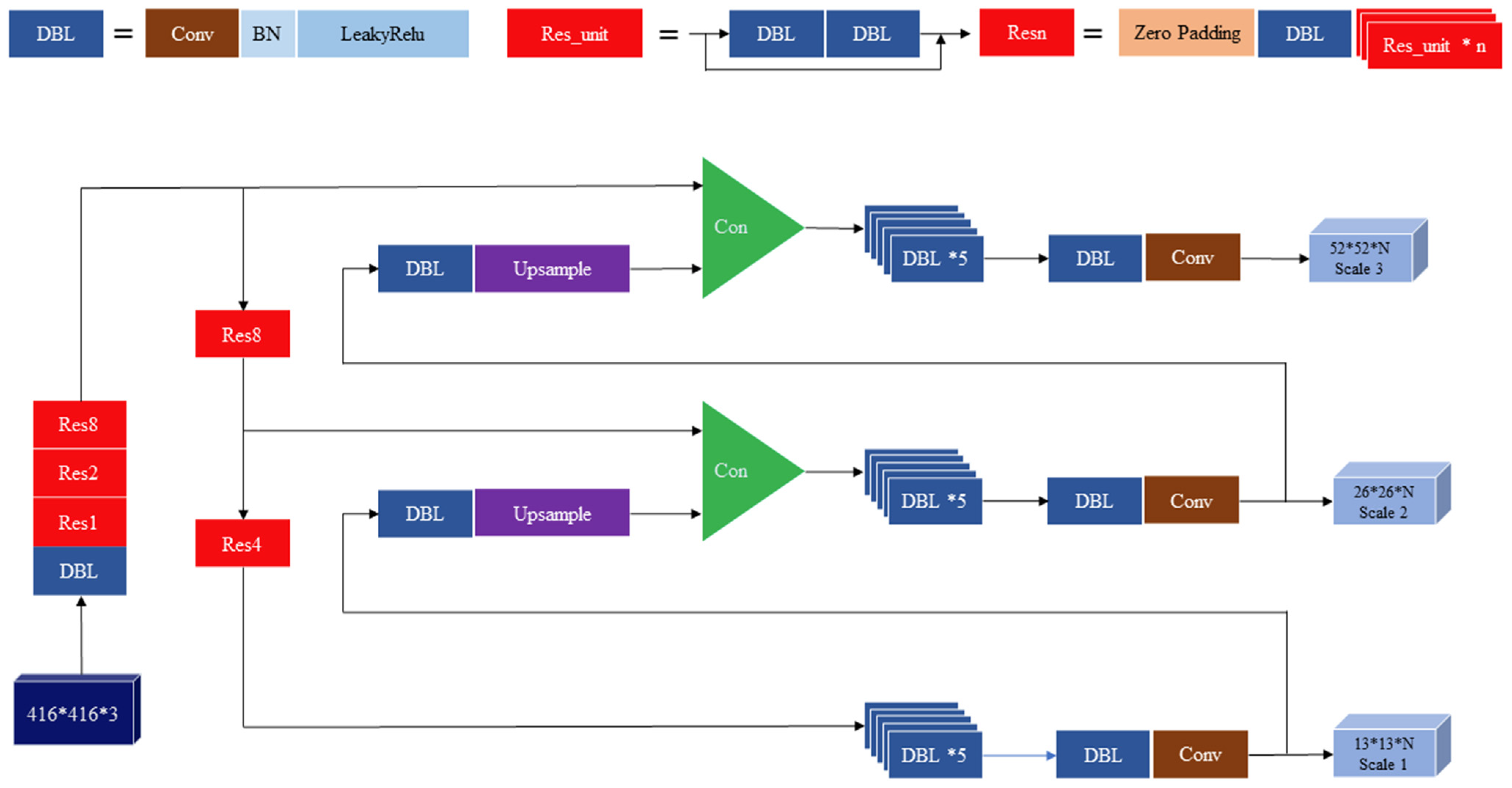

We introduce the YOLO-LIO algorithm to address the challenge of detecting objects across multiple scales, such as tiny vehicles viewed from an elevated camera.

Figure 5 presents the YOLO-LIO architecture, highlighting several key improvements over YOLOv3.

Higher input resolution (640 × 640)

YOLO-LIO increases the input size from YOLOv3’s 416 × 416 to 640 × 640 to preserve finer spatial details. The motivation is to improve small-object detection, especially motorcycles and distant vehicles, by providing the model with more high-resolution information.

Additional detection scale (fourth scale).

YOLOv3 uses three detection scales, but YOLO-LIO adds a fourth scale specifically designed for the smallest objects in the frame. This decision is motivated by the traffic-camera scenario, in which far-field vehicles often occupy only a few pixels. The added scale expands coverage of the receptive field and improves detection robustness across extreme size variations.

Enhanced feature fusion for small-object detection.

Feature maps downsampled by 8× are upsampled and fused with 4× features, enriching the shallow layers with deeper semantic information. This targeted fusion is introduced to strengthen the detection of small vehicles without incurring high computational costs.

Additional residual blocks (Res4).

YOLO-LIO incorporates two additional residual units at the finer scale (scale 4). This modification increases representational depth where detailed features are extracted, improving the network’s ability to capture subtle vehicle patterns. The design choice balances accuracy and computational efficiency, ensuring suitability for deployment on the Jetson Nano.

These improvements collectively produce a more capable multi-scale detector, enabling YOLO-LIO to identify vehicles of varying sizes with higher accuracy and stability compared to YOLOv3.

Figure 5.

Structural overview of the YOLO-LIO architecture with enhanced multi-scale detection and additional residual blocks at the fine-scale level.

Figure 5.

Structural overview of the YOLO-LIO architecture with enhanced multi-scale detection and additional residual blocks at the fine-scale level.

3.4.1. YOLO-LIO Feature Extraction with Extended Residual Blocks

The feature extraction process follows the general structure of YOLOv3 but is modified to support deeper, more context-aware features in selected layers. YOLO-LIO employs four distinct residual blocks, Res2, Res8, Res8, and Res4, chosen intentionally to create a balanced feature hierarchy:

This structured distribution of residual units is intentionally designed rather than arbitrary to balance depth, feature diversity, and computational constraints.

3.4.2. Four-Scale Multi-Scale Detection in YOLO-LIO

Multi-scale detection to detect different sizes of objects is achieved using YOLO-LIO. This is done by generating outputs on four different scales. We start by upsampling deeper feature maps and fusing them with shallower feature maps within a multi-level deep feature structure. The production of each scale is thus geared towards identifying objects within a specific size range, allowing the network to be adept at seeing small, medium, large, and most significant objects.

YOLO-LIO ultimately outputs four multi-scale predictions, which accounts for different levels of feature abstraction at the multi-scaled area for detection. The network generates these outputs by applying a set of convolutional layers to the combined feature maps from the various layers.

Having multi-scale context allows YOLO-LIO to detect objects even across more variegated scales have more time to ensure that the YOLO-LIO is accurate.

3.5. Vehicle Counting Using Dual-Line Virtual Zones

The authors use a Virtual Zone to ensure that vehicle detection is targeted to specific areas, enhancing vehicle recognition accuracy and computational efficiency [

32]. This Virtual Zone uses two horizontal virtual lines: one at the top for “check-in” detection and a second at the bottom for “check-out” detection. It can accurately count vehicles and determine their movement in the region using a dual-line system that tracks both entry and exit into the Virtual Zone.

The YOLO-LIO detection framework is employed to detect and label objects in the video feed. The top line is the entrance; as a vehicle passes it, the system checks it in and monitors its movement. When the car passes the bottom line, the vehicle is “checked out,” and the tracking process is complete. This ensures that different vehicles passing through only the top line or the bottom line will not be counted, thus reducing the false positives and anything that might be irrelevant.

The system effectively tracks, classifies, and counts each vehicle as it travels through the Virtual Zone, utilizing the top line (check-in) and the bottom line (check-out). This method guarantees excellent vehicle detection and tracking accuracy, which makes it well-suited for traffic and vehicle flow monitoring and intelligent transportation systems applications.

3.6. Displacement-Based Speed Estimation and Validation

Vehicle speed estimation in this study is performed by measuring the displacement of a detected vehicle between two positions in consecutive video frames using a standard Euclidean distance model [

33]. Let

and

denote the initial and final pixel coordinates of a tracked vehicle in the image plane. The pixel displacement

D is computed as:

To ensure temporal stability, the system tracks the vehicle displacement over 15 consecutive frames, which corresponds to a fixed time interval of

s, based on the known frame rate of the video stream. The frame rate information is obtained directly from the camera metadata, ensuring precise temporal alignment between measurements.

The vehicle speed

is then calculated as:

where

represents the measured pixel displacement,

denotes the elapsed time interval, and

is a pixel-to-real-world conversion factor used to transform pixel displacement into physical distance (meters). This conversion factor is derived through camera calibration and depends on the camera installation parameters, including mounting height, viewing angle, focal length, and intrinsic calibration parameters.

To validate the accuracy of the proposed speed estimation approach, an Intel RealSense D455 depth camera was employed as an external measurement device. The RealSense D455 provides synchronized RGB and depth data, enabling reliable estimation of real-world object displacement based on depth information. The depth measurements obtained from the D455 were used as ground-truth speed references to validate the estimated speeds produced by the proposed YOLO-LIO-based system. During the experiments, the RealSense D455 was rigidly mounted alongside the RGB camera and calibrated to ensure spatial alignment between the detection and depth measurement regions. The speed values estimated by the YOLO-LIO framework were compared with depth-based displacement measurements from the RealSense D455 over the same temporal intervals. The resulting speed deviations were analyzed to quantify estimation accuracy and validate the effectiveness of the proposed approach under real-world traffic conditions.

3.7. Algorithmic Comparison and System Integration

The YOLOv3 Algorithm 1. uses three detection scales to recognize small, medium, and large objects, thereby focusing on real-time object detection [

34]. It leverages three residual blocks of varying depths, enabling more effective feature extraction and delivering three detection results across the network at different scales, thereby accurately identifying objects across scales.

| Algorithm 1: YOLOv3 |

| 1 | function YOLOv3 (input): # 416 × 416 |

| 2 | # Feature Extraction |

| 3 | × = DBL(input) |

| 4 | ×1 = Resn(×, 1) # Res1 |

| 5 | ×2 = Resn(×1, 2) # Res2 |

| 6 | ×3 = Resn(×2, 8) # Res8 (Stage 1) |

| 7 | ×4 = Resn(×3, 8) # Res8 (Stage 2) |

| 8 | ×5 = Resn(×4, 4) # Res4 |

| 9 | |

| 10 | # Multi Scale |

| 11 | scale1 = Conv(DBL(×5)) # 13 × 13 (Larger objects) |

| 12 | scale2 = Conv(DBL(Upsample(scale1) + ×4)) # 26 × 26 (Medium objects) |

| 13 | scale3 = Conv(DBL(Upsample(scale2) + ×3)) # 52 × 52 (Small objects) |

| 14 | return [scale1, scale2, scale3] # Three output scales |

YOLO-LIO Algorithm 2. YOLO-LIO is a modified YOLOv3 that improves the detection effect by adding a fourth detection scale. YOLO-LIO can detect smaller objects, and incorporating an additional residual block (Res4) allows it to capture more details than YOLOv3. With four output scales, YOLO-LIO improves detection for larger objects while also refining detection for smaller objects, maximizing control over the optimization of YOLOv3’s real-time processing capabilities [

35,

36].

| Algorithm 2: YOLO-LIO |

| 1 | function YOLO_LIO (input): #640 × 640 |

| 2 | # Feature Extraction |

| 3 | × = DBL(input) |

| 4 | ×1 = Resn(×, 1) # Res1 |

| 5 | ×2 = Resn(×1, 2) # Res2 (Stage 1) |

| 6 | ×3 = Resn(×2, 8) # Res8 (Stage 2) |

| 7 | ×4 = Resn(×3, 8) # Res8 (Stage 3) |

| 8 | ×5 = Resn(×4, 4) # Res4 |

| 9 | |

| 12 | # Multi Scale |

| 13 | scale1 = Conv(DBL(×5)) # 20 × 20 (Largest objects) |

| 14 | scale2 = Conv(DBL(Upsample(scale1) + ×4)) # 40 × 40 (Larger objects) |

| 15 | scale3 = Conv(DBL(Upsample(scale2) + ×3)) # 80 × 80 (Medium objects) |

| 16 | Scale4 = Conv(DBL(Upsample(scale3) + ×2)) # 160 × 160 (Smallest objects) |

| 17 | return [scale1, scale2, scale3, scale4] # Four output scales |

The proposed method is a Traffic System that aims to improve vehicle detection and make the detection processes more efficient within the system.

Figure 6 gives a concrete example of the Traffic System framework.

The camera is positioned at an elevation of 4 m, considered the optimal height for accurate and precise vehicle detection.

YOLO-LIO serves as the primary vehicle-detection network and has been fine-tuned to improve detection accuracy.

Vehicle counting is performed by establishing a horizontal reference line across the video frame, with vehicles counted as they cross it. To ensure counting accuracy, the system classifies detections based on YOLO-LIO object categories.

In addition to object detection and counting, the system integrates a displacement-based speed estimation module that analyzes each vehicle’s motion across sequential video frames. YOLO-LIO provides consistent object tracking and positional updates, enabling the system to compute vehicle speeds as an essential component of its overall traffic-monitoring capability.

Figure 6.

Traffic system framework.

Figure 6.

Traffic system framework.

4. Result and Analysis

In this work, multiple datasets and object detection algorithms are utilized to benchmark the proposed YOLO-LIO system. The initial results indicate that the proposed system performs effectively and demonstrates strong potential for real-world deployment. All experiments were fully recorded using video acquisition equipment, and each experimental setting was repeated twenty times to ensure the reliability and consistency of the reported results.

System performance is evaluated using two complementary categories of metrics. First, confusion matrix-based metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 Score, are employed to assess classification and detection performance at the instance level [

37]. These metrics provide a comprehensive view of the system’s ability to identify vehicles while minimizing false detections and ensuring correct detections. Second, detection performance is further evaluated using Mean Average Precision (mAP), an Intersection over Union (IoU)-based metric rather than a confusion-matrix-derived measure. In this study, mAP is computed using an IoU threshold of 0.5 (mAP@0.5), where a detection is considered correct when the overlap between the predicted bounding box and the ground-truth annotation exceeds the specified threshold. This combined evaluation strategy enables a more accurate and detailed assessment of the proposed system’s detection capability. The results demonstrate the effectiveness and robustness of YOLO-LIO, highlighting its suitability for real-time traffic supervision and control applications under diverse operational conditions.

4.1. Datasets and Training Configuration

The dataset used in this study comprises four vehicle categories, Motorcycle, Car, Bus, and Truck, as summarized in

Table 1. These classes were selected to represent the most common vehicle types encountered in urban traffic environments. In addition to the custom dataset collected by the authors, several publicly available benchmark datasets, namely GRAM Road-Traffic Monitoring, UA-DETRAC, KITTI, and MAVD-Traffic, were incorporated to evaluate the generalization capability of the proposed framework. Each dataset was trained and evaluated independently to ensure a fair comparison and to generate the performance metrics reported in the

Section 4.

For the custom dataset, traffic videos were recorded in Beijing, China, using an overhead camera mounted at approximately 4 m above an elevated roadway. From these recordings, 3000 representative image frames were manually extracted and annotated using a standard labeling tool following the YOLO bounding-box format. The dataset captures diverse real-world conditions, including variations in illumination, weather, vehicle distance, and occlusion, to closely reflect practical deployment scenarios. This dataset was primarily used for real-world implementation and validation, as it matches the camera viewpoint, road geometry, and environmental characteristics of the deployment site. The custom dataset was divided into 70% training (2100 images), 15% validation (450 images), and 15% testing (450 images). To enhance model robustness and reduce overfitting, data augmentation techniques, including exposure adjustment, saturation modification, hue shifting, random rotation, and horizontal flipping, were applied to the training subset only, resulting in an augmented training set of 8400 images.

To ensure consistency across all datasets, every image, both from the custom dataset and public benchmarks, was resized to 640 × 640 pixels to meet Darknet input requirements. All annotations were converted into YOLO-compatible text format, and dataset splits were arranged individually for each dataset. Model training was conducted on an NVIDIA RTX 3090 Ti GPU (ASUS ROG Strix) for 10,000 iterations, using an adaptive learning-rate schedule to ensure stable convergence and weight regularization to mitigate overfitting. After training, the model was deployed and evaluated on an NVIDIA Jetson Nano platform to verify its real-time performance and suitability for low-power embedded traffic-monitoring systems.

4.2. Vehicle Detection Performance Evaluation

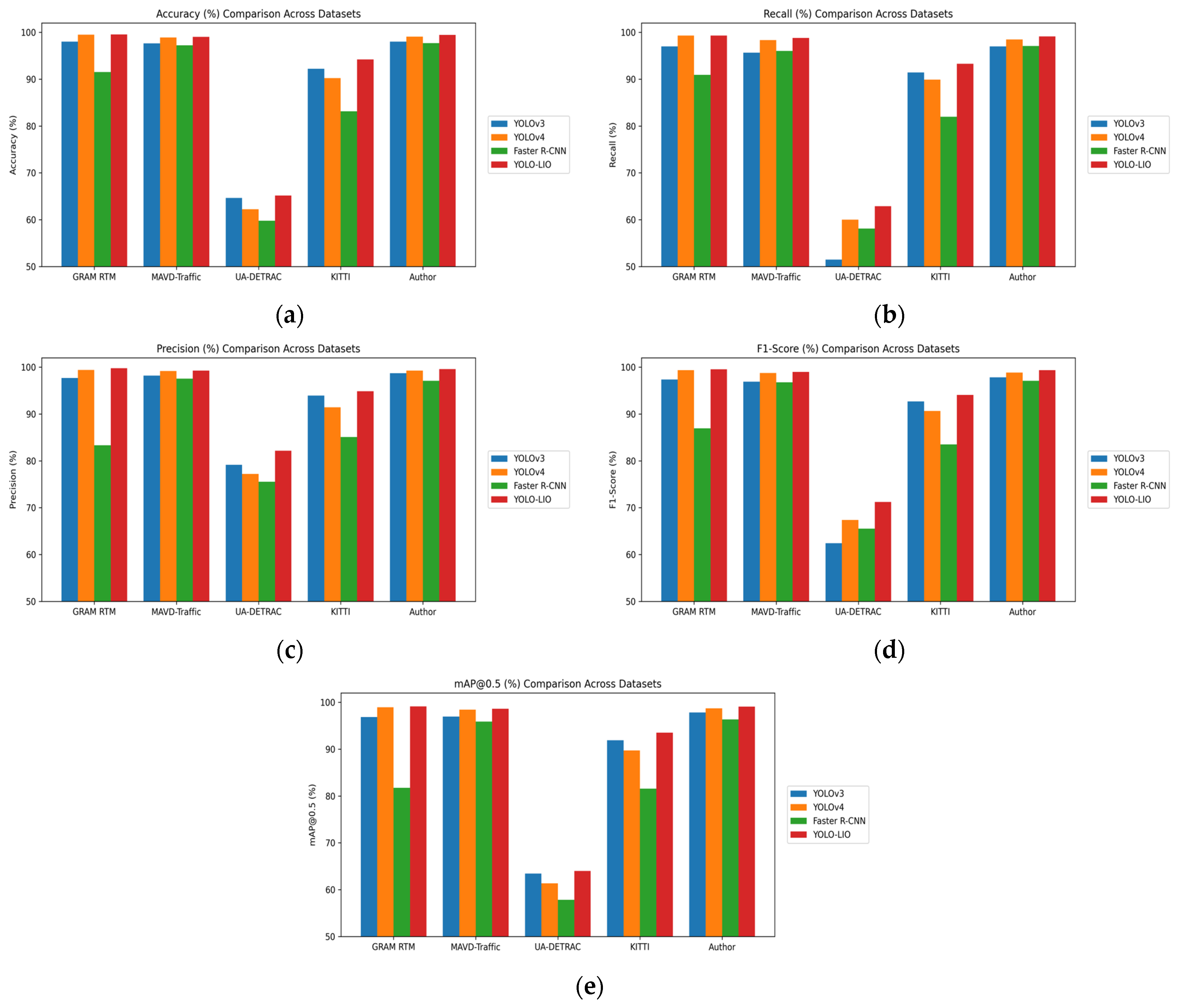

This study presents a comprehensive comparative analysis using five datasets: GRAM Road-Traffic Monitoring, MAVD-Traffic, UA-DETRAC, KITTI, and an additional dataset developed by the authors (referred to as the Author Dataset). These datasets were selected to represent diverse traffic conditions and environments, and dataset naming conventions were standardized to ensure clarity and consistency. To enhance the reliability and robustness of the experimental outcomes, ten independent trials were conducted for each dataset.

The performance evaluation compares four object detection algorithms, YOLOv3, YOLOv4, Faster R-CNN, and the proposed YOLO-LIO, across all five datasets using two complementary categories of evaluation metrics. First, confusion-matrix-based metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 Score, are used to assess detection-level classification performance. Second, detection quality is evaluated using Mean Average Precision (mAP), an Intersection over Union (IoU)-based metric, rather than a metric derived from the confusion matrix. In this study, all mAP results are computed using a fixed IoU threshold of 0.5 (mAP@0.5), which is commonly adopted in YOLO-based object detection benchmarks. A detection is considered correct when the IoU between the predicted bounding box and the ground-truth annotation exceeds 0.5.

The detailed vehicle detection results, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and mAP@0.5, for each algorithm across all datasets are reported in

Table 2. In addition,

Table 3 provides a comparative accuracy analysis between the proposed YOLO-LIO and previously reported results on the GRAM Road-Traffic Monitoring dataset. Visual comparisons of these evaluation metrics are presented in

Figure 7, offering further insight into the relative performance of each detection approach.

The experimental results reveal that YOLO-LIO consistently outperforms the other detection algorithms across all evaluated datasets. Specifically, YOLO-LIO achieved an outstanding accuracy of 99.55% on the GRAM Road-Traffic Monitoring dataset, 99.02% on MAVD-Traffic, 65.14% on UA-DETRAC, 94.21% on KITTI, and 99.45% on the Author Dataset. These results emphasize the exceptional vehicle detection capability and reliability of the YOLO-LIO framework.

Although YOLO-LIO demonstrates strong performance across most datasets, its results on UA-DETRAC are comparatively lower. This outcome is expected, as UA-DETRAC is a substantially more challenging benchmark characterized by heavy occlusions, overlapping vehicles, dense traffic, nighttime scenes, adverse weather conditions (rain and fog), motion blur, and significant variation in object scales and camera viewpoints. These factors introduce considerable visual noise and increase the difficulty of consistent object detection for all evaluated algorithms. Furthermore, differences in class annotations within UA-DETRAC necessitated remapping to the four-class structure adopted in this study, which occasionally led to class inconsistencies and reduced performance.

UA-DETRAC also contains frequent partially occluded and overlapping vehicle conditions under which conventional YOLO-based detectors may merge multiple vehicles into a single bounding box or fail to detect heavily obstructed objects. While YOLO-LIO enhances multi-scale feature extraction compared to its predecessors, it does not incorporate dedicated occlusion-handling mechanisms. Therefore, future improvements may include integrating occlusion-aware detection strategies, temporal consistency modeling, or advanced tracking modules to enhance robustness in dense, complex real-world traffic scenarios.

A further comparative analysis was conducted against five prior studies that utilized the GRAM Road-Traffic Monitoring dataset between 2017 and 2024. As detailed in

Table 3, YOLO-LIO demonstrates superior accuracy compared to these previous methods, thereby reinforcing the proposed model’s advanced detection performance and practical applicability.

In addition,

Figure 8 showcases several qualitative detection results from the traffic monitoring system using YOLO-LIO. The results display the model’s ability to accurately detect and classify various vehicle types in real-world traffic environments. While the majority of detections were accurate, minor detection errors were also observed.

These results confirm the high precision and effectiveness of YOLO-LIO, while also highlighting areas for potential future improvement to address misclassification cases.

4.3. Vehicle Counting Performance

To ensure reliable evaluation, the experiment was conducted using ten video sequences, each containing approximately 50–60 vehicles.

Table 4 presents the vehicle-counting results obtained from these tests. Overall, the proposed method achieved high counting accuracy across the evaluated videos.

However, some challenges arose due to inconsistencies in class labeling during detection. As vehicles crossed the input and output counting lines, changes in the predicted class within the same bounding box occasionally occurred, which led to miscounts and reduced accuracy for specific vehicle categories. While the car class maintained stable, highly consistent results, other classes showed occasional fluctuations that affected counting precision. This limitation has been acknowledged and discussed in the revised manuscript.

4.4. Speed Estimation Accuracy

This section presents the experimental results of the vehicle speed detection analysis. To validate the proposed speed estimation method, the predicted vehicle speeds obtained from the YOLO-LIO framework are compared against ground truth measurements provided by an external speed-measurement device, namely the Intel RealSense D455 depth camera. This comparison assesses the accuracy and reliability of the proposed approach under real-world traffic conditions. The RealSense D455 provides synchronized RGB and depth data, enabling accurate estimation of real-world object displacement from depth measurements. During the experiments, the D455 was mounted alongside the RGB camera and calibrated to ensure spatial alignment between the detection region and the depth sensing area. The depth-based speed measurements obtained from the D455 were treated as ground truth references and compared with the speed predictions generated by the proposed method over identical temporal intervals.

The speed detection results for 20 representative vehicles are summarized in

Table 5, which reports the ground truth speed measured by the RealSense D455, the corresponding speed predicted by the proposed method, the absolute speed difference, and the relative error percentage.

As shown in

Table 5, the proposed method achieves an average relative error of only 1.3%, indicating high accuracy in vehicle speed estimation. Such performance demonstrates that the proposed YOLO-LIO-based speed detection approach provides reliable and precise real-time speed measurements, making it suitable for deployment in practical traffic monitoring systems. Continuous operation and long-term monitoring further confirm the robustness and applicability of the proposed framework in real-world scenarios.

4.5. Real-Time Performance and Computational Analysis

To support the claim of real-time deployment on low-power embedded systems, we evaluated the computational performance of the proposed YOLO-LIO and several baseline detectors on an NVIDIA Jetson Nano platform. The Jetson Nano is equipped with a quad-core ARM Cortex-A57 CPU, a 128-core Maxwell GPU, and 4 GB of LPDDR4 memory, making it a representative embedded device for edge-based intelligent traffic-monitoring applications.

All experiments were conducted under real-world deployment conditions, with the batch size set to 1, to reflect practical online inference scenarios. The reported inference time corresponds to the average end-to-end forward-pass latency per frame, excluding video decoding and visualization overhead.

As shown in

Table 6, Faster R-CNN exhibits significantly higher inference latency, achieving only 10–15 FPS, which makes it unsuitable for real-time processing on low-power embedded hardware. In contrast, YOLOv3 and YOLOv4, as single-stage detectors, demonstrate substantially lower inference times and consistently operate within the real-time range. Despite using a higher input resolution (640 × 640) and introducing an additional detection scale, YOLO-LIO achieves inference speeds comparable to YOLOv3, maintaining a stable frame rate of 25–30 FPS on Jetson Nano. This indicates that the architectural enhancements in YOLO-LIO introduce only marginal computational overhead. Overall, these results confirm that YOLO-LIO maintains real-time performance on resource-constrained embedded platforms, while providing enhanced multi-scale detection capability. This validates the suitability of the proposed framework for real-time intelligent traffic monitoring and edge-based deployment.

5. Conclusions

The YOLO-LIO is an enhanced vehicle detection system capable of identifying motorbikes, cars, buses, and trucks. The authors compare, four algorithms, YOLOv3, YOLOv4, Faster R-CNN, and YOLO-LIO, across five datasets: GRAM Road-Traffic Monitoring, MAVD-Traffic, UA-DETRAC, KITTI, and the Author Dataset. Among these datasets, YOLO-LIO achieved the highest performance, reaching over 99.55% accuracy on the GRAM Road-Traffic Monitoring dataset. These results demonstrate the substantial effectiveness of YOLO-LIO and its suitability for real-world applications.

In this work, an integrated and efficient traffic monitoring system was developed by combining the YOLO-LIO framework with Jetson Nano hardware to streamline the entire detection pipeline. Key optimizations, such as the use of Virtual Zones, were applied to eliminate irrelevant regions, thereby reducing computational load and power consumption. Additional preprocessing steps, including grayscale conversion, Laplacian variance analysis, and median filtering, further improved detection reliability. A multi-threading approach was implemented to accelerate processing and enhance real-time performance.

Furthermore, the system incorporates a displacement-based speed estimation module that utilizes YOLO-LIO continuous detection and tracking outputs to estimate vehicle speeds accurately. This integration ensures the system functions not only as a vehicle detector but also as a complete traffic-monitoring solution. Consequently, the authors conclude that YOLO-LIO is a robust, accurate, and scalable framework for traffic monitoring, vehicle detection, counting, and speed estimation, particularly when deployed on the Jetson Nano for real-time applications.

6. Limitations and Future Work

Although YOLO-LIO demonstrates strong performance in multi-scale vehicle detection, real-time processing, and overall traffic-monitoring reliability, several limitations remain, highlighting opportunities for further improvement. Temporal incoherence may occur because the system operates frame-by-frame without a dedicated tracking module, leading to occasional object ID switches and positional jitter that degrade speed estimation accuracy and reduce visual stability in fast-moving traffic scenes. Classification instability and misclassification errors also arise in challenging conditions such as occlusion, overlapping vehicles, and low-resolution distant targets, particularly affecting motorcycles and small far-field objects with limited pixel representation. Counting inaccuracies may still occur in dense or multi-lane traffic when vehicles overlap or cross the Virtual Zone boundaries simultaneously, leading to undercounting or double-counting events. Additionally, speed estimation remains highly sensitive to camera calibration, with changes in tilt, vibration, or environmental conditions distorting pixel-to-distance scaling and introducing systematic measurement errors. Furthermore, despite the inclusion of a small-object detection scale, vehicles located beyond approximately 40–50 m remain difficult to detect reliably due to low pixel density and atmospheric distortion, reducing performance in wide intersections or long-distance roadway environments.

Future development of the YOLO-LIO framework may therefore focus on several key directions to address these challenges and further enhance system robustness. Integrating a dedicated tracking module, such as DeepSORT, ByteTrack, or OC-SORT, would significantly improve temporal coherence by maintaining consistent object identities and smoothing object trajectories, thereby increasing the reliability of speed estimates and reducing ID switching in crowded scenes. Hybrid feature extraction approaches such as transformer-based backbones, attention-enhanced decoders, or CNN-ViT fusion models could be explored to further reduce misclassification, particularly for small, distant, or partially occluded vehicles. Adaptive and automatic calibration techniques based on vanishing-point estimation, ground-plane analysis, or multi-view geometry could minimize dependence on manual calibration and ensure stable speed measurement over long-term deployment. Additionally, enhanced counting mechanisms, such as multi-line strategies, stereo depth estimation, or 3D virtual zones, may help address inaccuracies in dense multi-lane environments. From a broader perspective, future research should also consider improving scalability by leveraging cloud-edge collaboration and integrating with I2X/V2X communication frameworks, enabling YOLO-LIO to support large-scale intelligent transportation systems through real-time data sharing and city-wide traffic analytics. Finally, performance optimization techniques such as quantization, tensor pruning, and lightweight architectural variants may be applied to increase computational efficiency on edge devices like Jetson Nano and Jetson Orin, ensuring suitability for low-power, real-time innovative mobility applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z. and R.M.; methodology, H.Z., H.G. and R.M.; software, R.M. and M.Y.; validation, H.Z., and H.G.; formal analysis, R.M., G.P.N.H. and A.M.; investigation, R.M. and H.Z.; resources, R.M. and H.Z.; data curation, R.M., M.Y., R.R. and D.R.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M.; writing—review and editing, H.Z. and H.G.; visualization, R.M.; supervision, H.Z. and H.G.; project administration, H.Z. and H.G.; funding acquisition, H.Z. and H.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research work was financially supported by the 2019 China Ministry of Education University-Industry Collaborative Education Program and Datang Mobile Communication Equipment Co., Ltd., Project Number: 201902094001.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Tangshan Research Institue for give the chance for make research this project and sup-ported by the Innovation Research Ceter for New Energy and Electric Drive Systems, Microwave and Terahertz Technologies, and Digital Performance and Simulation Technologies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nigam, N.; Singh, D.P.; Choudhary, J. A Review of Different Components of the Intelligent Traffic Management System (ITMS). Symmetry 2023, 15, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Fan, M. Emergency Routing Protocol for Intelligent Transportation Systems Using IoT and Generative Artificial Intelligence. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muwardi, R.; Qin, H.; Gao, H.; Ghifarsyam, H.U.; Hajar, M.H.I.; Yunita, M. Research and Design of Fast Special Human Face Recognition System. In Proceedings of the 2020 2nd International Conference on Broadband Communications, Wireless Sensors and Powering (BCWSP), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 28–30 September 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuhadar, C.; Tsao, H.N. A Computer Vision Sensor for AI-Accelerated Detection and Tracking of Occluded Objects. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2022, 4, 2100285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. Analysis of Object Detection Performance Based on Faster R-CNN. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1827, 012085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, C. Improved YOLOv3 Model for miniature camera detection. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 142, 107133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, W.; Zhang, H.; Changming, Z.; Zhipeng, L.; Yuanze, W. Improved YOLOv4 for real-time detection algorithm of low-slow-small unmanned aerial vehicles. J. Appl. Opt. 2024, 45, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhan, J.; Duan, C.; Guan, X.; Lu, P.; Yang, K. A Review of Vehicle Detection Techniques for Intelligent Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 3811–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-Z.; Chang, C.-M.; Yu, C.-W.; Chen, Y.-L. A Real-Time Vehicle Detection System under Various Bad Weather Conditions Based on a Deep Learning Model without Retraining. Sensors 2020, 20, 5731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudawi, N.A.; Qureshi, A.M.; Abdelhaq, M.; Alshahrani, A.; Alazeb, A.; Alonazi, M.; Algarni, A. Vehicle Detection and Classification via YOLOv8 and Deep Belief Network over Aerial Image Sequences. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xianbao, C.; Guihua, Q.; Yu, J.; Zhaomin, Z. An improved small object detection method based on Yolo V3. Pattern Anal. Appl. 2021, 24, 1347–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, M.; Luo, J.; Wang, Z.; Luo, H. Adaptive feature fusion with attention mechanism for multi-scale target detection. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 33, 2769–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodmann, P.; Papadimitriou, G.; Gizopoulos, D.; Rech, P. The Impact of SoC Integration and OS Deployment on the Reliability of Arm Processors. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Symposium on Performance Analysis of Systems and Software (ISPASS), Stony Brook, NY, USA, 28–30 March 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Whatmough, P.N.; Donato, M.; Ko, G.G.; Brooks, D.; Wei, G.-Y. SMIV: A 16-nm 25-mm2 SoC for IoT With Arm Cortex-A53, eFPGA, and Coherent Accelerators. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2022, 57, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Zhu, L.; Yu, F.R.; Tang, T. Edge Intelligence in Intelligent Transportation Systems: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 8919–8944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elassy, M.; Al-Hattab, M.; Takruri, M.; Badawi, S. Intelligent transportation systems for sustainable smart cities. Transp. Eng. 2024, 16, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, A.A.; Malami, S.I.; Alanazi, F.; Ounaies, W.; Alshammari, M.; Haruna, S.I. Sustainable Traffic Management for Smart Cities Using Internet-of-Things-Oriented Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS): Challenges and Recommendations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, K.; Strauss, A.; Cao, M. Real-time detection of concrete cracks via enhanced You Only Look Once Network: Algorithm and software. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2024, 195, 103691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Li, S. Object Detection Algorithm Based on Improved YOLOv3. Electronics 2020, 9, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Han, Z.; Xu, H.; Liu, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, K. YOLOv3-Lite: A Lightweight Crack Detection Network for Aircraft Structure Based on Depthwise Separable Convolutions. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.-C.; Sun, H.-M.; Liu, Y.-B.; Jia, R.-S. Mini-YOLOv3: Real-Time Object Detector for Embedded Applications. IEEE Access 2020, 7, 133529–133538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Yang, T.; Tong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, S.; Zhou, R. Multi-Scale Ship Detection From SAR and Optical Imagery Via A More Accurate YOLOv3. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 6083–6101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H. Real-time edge computing on multi-processes and multi-threading architectures for deep learning applications. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2022, 92, 104554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olagoke, A.S.; Ibrahim, H.; Teoh, S.S. Literature Survey on Multi-Camera System and Its Application. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 172892–172922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, K.; Syed, A.B.; Zhu, X.; Pauly, J.M.; Vasanawala, S.V. Automated MRI Field of View Prescription from Region of Interest Prediction by Intra-Stack Attention Neural Network. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žeger, I.; Šetka, I.; Marić, D.; Grgić, S. Exploring Image Decolorization: Methods, Implementations, and Performance Assessment. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, D.; Lu, R.; Hu, B.; Yin, J.; Shen, S.; Xu, T.; Lang, X. YOLO-MIF: Improved YOLOv8 with Multi-Information fusion for object detection in Gray-Scale images. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 62, 102709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wu, Y.; Liu, J.; Sun, Z. Improved YOLOv3 Network for Insulator Detection in Aerial Images with Diverse Background Interference. Electronics 2021, 10, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.S.; Khan, M.; Alharbi, Y. Fast Local Laplacian Filter Based on Modified Laplacian through Bilateral Filter for Coronary Angiography Medical Imaging Enhancement. Algorithms 2023, 16, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; Aguiar, M.; Welfer, D.; Belloni, B. A New Approach for Detecting Fundus Lesions Using Image Processing and Deep Neural Network Architecture Based on YOLO Model. Sensors 2022, 22, 6441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wu, J.; Tian, Y.; Tang, H.; Guo, X. Real-Time Vehicle Detection Based on Improved YOLO v5. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Fang, H.; Wang, N.; Zhang, C.; Dong, J.; Hu, H. Automatic Detection and Counting System for Pavement Cracks Based on PCGAN and YOLO-MF. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 22166–22178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuraimi, M.A.B.; Zaman, F.H.K. Vehicle Detection and Tracking using YOLO and DeepSORT. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 11th IEEE Symposium on Computer Applications & Industrial Electronics (ISCAIE), Penang, Malaysia, 3–4 April 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Fan, J. A lightweight object detection algorithm based on YOLOv3 for vehicle and pedestrian detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Asia-Pacific Conference on Image Processing, Electronics and Computers (IPEC), Dalian, China, 14–16 April 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionnie, R.; Andika, J.; Alaydrus, M. A New Approach to Recognize Faces Amidst Challenges: Fusion Between the Opposite Frequencies of the Multi-Resolution Features. Algorithms 2024, 17, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionnie, R.; Apriono, C.; Gunawan, D. Eyes versus Eyebrows: A Comprehensive Evaluation Using the Multiscale Analysis and Curvature-Based Combination Methods in Partial Face Recognition. Algorithms 2022, 15, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydarian, M.; Doyle, T.E.; Samavi, R. MLCM: Multi-Label Confusion Matrix. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 19083–19095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.-Y.; Hsu, T.-C.; Wu, Y.-F.; Chen, J.-J.; Tseng, Y.-C. Efficient Vehicle Counting Based On Time-Spatial Images By Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 18th International Conference on Mobile Ad Hoc and Smart Systems (MASS), Denver, CO, USA, 4–7 October 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-J.; Jeng, S.-Y.; Lioa, H.-W. A Real-Time Vehicle Counting, Speed Estimation, and Classification System Based on Virtual Detection Zone and YOLO. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 1577614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Liu, M.; Ye, Z. An advanced YOLOv3 method for small-scale road object detection. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 112, 107846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, H.; Lin, S. Quantizing YOLOv5 for Real-Time Vehicle Detection. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 145601–145611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahremannezhad, H.; Shi, H.; Liu, C. Object Detection in Traffic Videos: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 6780–6799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.; Azarmi, M.; Mir, F.M.P. 3D-Net: Monocular 3D object recognition for traffic monitoring. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 227, 120253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Kumar, R.; Gupta, M.; Kumar, M.; Obaid, A.J.; Ved, C. YOLO-Based Vehicle Detection and Counting for Traffic Control on Highway. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Advancement in Computation & Computer Technologies (InCACCT), Gharuan, India, 2–3 May 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |