1. Introduction

The proliferation of data-driven educational technologies has transformed how institutions collect, analyze, and act upon student information. Predictive models in Educational Data Mining (EDM) and Learning Analytics (LA) can identify students at risk of failure, recommend personalized interventions, and inform policy decisions. However, such innovations are often constrained by data limitations: real educational datasets are scarce, incomplete, or tightly regulated by ethical and legal frameworks such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [

1,

2].

Synthetic data generation has emerged as a transformative response to these challenges. By simulating the statistical and structural characteristics of real data, it enables research and model development without direct exposure of sensitive records. Synthetic datasets preserve the utility of original data while offering substantial gains in privacy, accessibility, and scalability. In domains such as healthcare [

3] and finance [

4], synthetic data has already been shown to improve data availability and reproducibility. However, in education, systematic benchmarking of generative models remains limited, and the trade-offs among utility and privacy are still poorly understood.

Recent studies highlight the increasing interest in synthetic data generation for educational applications. Emerging approaches demonstrate that it is possible to create realistic student data while addressing critical concerns such as privacy and predictive utility. This body of work reflects a broader shift from methods focusing solely on replicating data distributions toward multi-objective generative frameworks that aim to balance data fidelity, ethical considerations, and privacy preservation. These developments underscore the potential of synthetic data to support responsible, large-scale experimentation in education while mitigating risks associated with the use of real student records.

Despite these developments, three challenges persist. First, there is a lack of reproducible, standardized pipelines comparing statistical and deep generative synthesizers on authentic educational data. Second, quantitative privacy assessment is often omitted, limiting the interpretability of synthetic data’s ethical implications. Third, cross-course or multi-context benchmarking remains rare, preventing robust generalization across different educational environments.

This study addresses these gaps by evaluating four representative generative models, namely Gaussian Copula, Conditional Tabular Generative Adversarial Networks (CTGAN), CopulaGAN, and Tabular Variational Auto Encoders (TVAE), on six undergraduate courses at a European university. We assess whether models trained on synthetic data can replicate the predictive performance of real data in student performance modeling and to what extent statistical and deep learning synthesizers differ in their capacity to preserve realism and reduce privacy risks. In doing so, our research contributes to the emerging agenda of responsible synthetic data generation in education, offering a replicable methodology and empirical foundation for privacy-preserving LA. In summary, this work contributes: (i) a replicable SDV-based benchmarking pipeline tailored to educational tabular data; (ii) an empirical comparison of statistical and deep generative models across six course datasets and (iii) an evidence-based discussion of open challenges for privacy-aware and reproducible EDM/LA. Therefore, we consider this study an initial but foundational step toward the systematic evaluation and validation of artificially generated educational datasets. By demonstrating the potential of synthetic data to support large-scale experimentation without exposing sensitive or personally identifiable student information, our study contributes to emerging efforts that seek to balance data utility, ethical responsibility, and privacy preservation in the educational field.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of prior research on synthetic data generation within the fields of EDM and LA.

Section 3 describes the dataset employed in this study, the data synthesis techniques utilized, and the experimental design, alongside the proposed methodology.

Section 4 presents the results of the experiments, while

Section 5 offers a detailed discussion of the findings and their theoretical and practical implications. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the study by highlighting its limitations and suggesting directions for future research.

2. Synthetic Data in Education

In recent years, the use of synthetic data in the educational domain has gained significant momentum, driven by the need to enable reproducible research, privacy preservation, and large-scale experimentation in the fields of EDM and LA. Early foundational work, such as that by Berg et al. [

5], conceptualized synthetic data generation not merely as a mechanism for privacy protection, but as a core infrastructure component for advancing educational research. They highlighted that the scarcity of openly accessible and ethically shareable educational datasets limits reproducibility and benchmarking. To address this, they proposed a reference synthetic data generator capable of producing statistically representative yet privacy-safe datasets, laying the conceptual groundwork for later empirical studies that operationalized synthetic data generation through modern generative models.

Building on this foundation, Zhan et al. [

6] conducted one of the first systematic evaluations of generative models for privacy-preserving data synthesis in education. Their study assessed multiple student-data synthesizers, including those built with the Synthetic Data Vault (SDV) framework, across statistical fidelity, predictive utility, and privacy risk. While SDV-based approaches achieved strong distributional similarity and competitive performance, no single method consistently balanced utility and privacy across diverse datasets, highlighting the need for task-aware synthesis and standardized evaluation protocols.

Further empirical evidence for the benefits of synthetic data was provided by Farhood et al. [

7], who demonstrated that GAN-generated synthetic student data, including CTGANs and CopulaGANs, can meaningfully improve predictive models in educational settings. By comparing purely synthetic, mirrored, and hybrid datasets, they showed that augmenting real data with high-quality synthetic records enhances the predictive accuracy of various ML models while maintaining data fidelity, validated through density analysis, correlation metrics, and principal component analysis.

A rigorous evaluation framework for synthetic tabular data was introduced by Liu et al. [

8], assessing three generative methods (Gaussian Multivariate, Gaussian Copula and CTGAN) across resemblance, utility, and privacy dimensions. Their results confirmed that synthetic data can preserve predictive performance comparable to real data while significantly enhancing privacy protection, providing scenario-specific guidance for method selection. Similarly, Iloh et al. [

9] compared traditional statistical approaches with deep generative models (CTGAN and Gaussian Copula) using the Open University Learning Analytics Dataset (OULAD). Their study highlighted that deep generative models, particularly CTGAN, replicate real educational patterns with high predictive performance while reducing re-identification risks, although trade-offs between utility and privacy remain inevitable.

Advancing methodological rigor, Liu et al. [

10] introduced a comprehensive framework to evaluate trade-offs among analytical utility, fairness, and privacy in educational data synthesis. By integrating quantitative metrics for each dimension, they demonstrated that optimizing one objective can negatively impact others, emphasizing the importance of multi-objective balance in responsible synthetic data generation. Similarly, the interplay between privacy and fairness was examined in [

11], showing that strategies minimizing privacy risks may compromise fairness, and vice versa, underscoring the need for context-aware approaches in education.

Recent innovations have explored hybrid and diffusion-based methods to further enhance synthetic data quality and ethical compliance. Khalil et al. [

12] combined transformer-based Large Language Models (LLMs) with CTGAN to generate richly structured synthetic student profiles, achieving high statistical fidelity, predictive performance, and low membership inference risk. Their findings show that this combined approach not only closely mimics real student data distributions but also enhances the flexibility and interpretability of synthetic profiles, contributing to a novel framework for realistic and privacy-conscious data generation in LA. Likewise, Kesgin [

13] proposed FairSYN-Edu, a diffusion-based framework that simultaneously optimizes data utility, fairness, and privacy. Unlike traditional GAN or VAE architectures, FairSYN-Edu integrates multi-objective optimization to jointly preserve data utility, fairness, and privacy. By leveraging denoising diffusion probabilistic models, it incrementally reconstructs realistic educational records while minimizing bias propagation and potential data leakage. The framework introduces fairness-aware loss functions to constrain demographic disparity and applies differential-privacy-inspired noise mechanisms to further reduce re-identification risk. Experimental results on real student datasets demonstrate that FairSYN-Edu achieves competitive predictive performance compared with CTGAN and TVAE while substantially narrowing fairness gaps across sensitive attributes.

A recent contribution closely aligned with our study investigates the use of TVAE-generated synthetic data to improve learning performance in educational contexts [

14]. The authors demonstrate that incorporating synthetic samples into semi-supervised pipelines can mitigate the limitations of scarce labeled data, leading to enhanced predictive accuracy and more stable model behavior. Their findings highlight the capacity of TVAE to preserve complex relationships in student-related features, thereby supporting downstream classification tasks. This work underscores the growing relevance of generative models in EDM and provides empirical evidence that synthetic data can serve not only as a privacy-preserving substitute for real data but also as an effective augmentation strategy; insights that complement and reinforce the motivations of the present study.

As shown in

Table 1, prior work has progressively shifted from conceptual privacy-preserving generators to GAN, diffusion, and fairness-aware synthetic data models.

3. Experimental Setup

The primary objective of this study is to investigate contemporary approaches to synthetic data generation within the educational field. Specifically, we examine the effectiveness of state-of-the-art generative models in producing high-fidelity synthetic datasets under authentic educational conditions. To this end, we collected detailed log data from multiple blended-learning courses delivered through the Moodle Learning Management System (LMS). Our aim is to determine whether synthetic data models trained on these real student interaction traces can generate data that closely replicates the statistical properties, behavioral patterns, and structural characteristics of the original datasets. In addition, we assess the extent to which the generated synthetic data can be reliably used in downstream Machine Learning (ML) tasks, such as student performance prediction.

3.1. Data Collection and Structure

The dataset used in this study comprises 1367 undergraduate students enrolled in six compulsory and laboratory courses delivered through face-to-face instruction at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (AUTH), Greece, during the academic years 2017–2018 and 2018–2019.

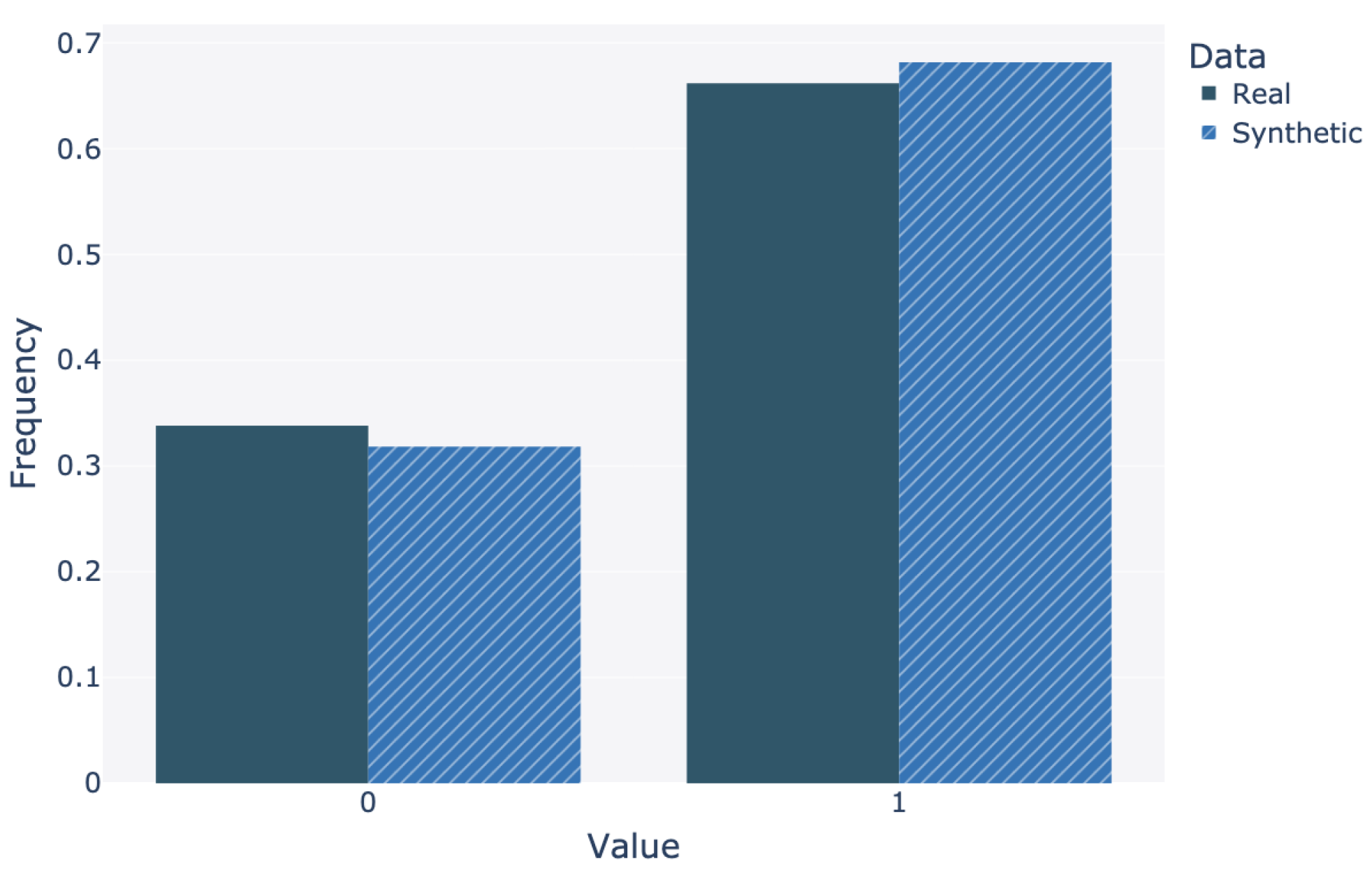

Figure 1 reports the output attribute distribution (pass/fail) for the students included in the analysis.

The university’s LMS provides a comprehensive collection of student and course-related data, encompassing demographic, academic, and engagement features. These features include demographic variables (e.g., gender, admission pathway), academic performance indicators (e.g., average grade from previous academic years, cumulative course average, number of courses passed or failed), and course-specific descriptors such as course type and instructional format. Academic performance is represented through multiple quantitative metrics, allowing for a detailed analysis of each student’s learning trajectory and prior achievement.

Instruction across the included courses is supported by the Moodle LMS, which integrates a wide range of digital learning resources and activities, including forums, pages, files, folders, URLs, and assignments. The dataset further includes detailed logs of students’ online learning behavior, capturing usage frequencies, interaction patterns, and engagement indicators for the various Moodle activities.

Table 2 presents a comprehensive overview of the dataset attributes employed in this study. The features span demographic, academic, and online engagement dimensions and serve as inputs for synthetic data generation as well as subsequent machine learning prediction tasks. The target variable, performance, denotes the student’s outcome in the final course examination, encoded as a binary pass–fail indicator.

3.2. Privacy Analysis

To evaluate the privacy properties of the dataset, we conducted a comprehensive analysis using established statistical disclosure control metrics, namely

k-anonymity [

15],

ℓ-diversity [

16],

t-closeness [

17], and uniqueness scores. The analysis focuses on the sensitive output attribute, as it directly reflects student academic performance, while the quasi-identifiers were selected to reflect realistic re-identification scenarios in the university context. The attributes used as quasi-identifiers are gender, condition, admission_mode, exam_period, reg_semester, as they are either demographic or administrative and could plausibly be known to an adversary.

The dataset satisfies k-anonymity with , meaning that at least one equivalence class contains a single individual when grouped by the selected quasi-identifiers. This result indicates that some student records are unique with respect to the quasi-identifier set and are therefore fully identifiable under a worst-case adversarial model. From a privacy standpoint, represents the weakest possible anonymity guarantee, implying that the dataset does not provide protection against identity disclosure without additional anonymization or generalization.

The dataset exhibits ℓ-diversity with , which implies that within at least one equivalence class, only a single grade value (pass or fail) is present, leading to complete attribute disclosure for individuals in that class. Consequently, once an individual is re-identified, their academic outcome can be inferred with certainty. This result highlights a lack of protection against attribute inference attacks.

The maximum t-closeness value across equivalence classes was found to be t = 0.662, indicating a substantial divergence between the distribution of grades within certain equivalence classes and the overall grade distribution in the dataset. In practical terms, this suggests that membership in some quasi-identifier groups strongly correlates with academic success or failure, thereby increasing the risk of probabilistic inference about the sensitive attribute even without exact re-identification.

Finally, approximately of records are unique with respect to the chosen quasi-identifiers. While the majority of students belong to larger equivalence classes, the presence of unique records significantly weakens the overall privacy guarantees and drives the high prosecutor risk observed above.

Taken together, the privacy metrics reveal that the dataset provides limited protection against both identity and attribute disclosure. Although the proportion of unique records is relatively small, the combination of , , and high t-closeness values indicates that certain students are highly vulnerable to re-identification and sensitive attribute inference. These findings suggest that the dataset, in its current form, is not suitable for public release without the application of privacy-preserving transformations such as generalization, suppression, or differential privacy mechanisms.

3.3. Fairness Evaluation

To assess algorithmic fairness with respect to the sensitive attribute gender (with categories male and female), we computed two widely used group fairness metrics: Demographic Parity Difference (DPD) [

18] and Equalized Odds Difference (EOD) [

19].

The DPD was found to be 0.0183, indicating a very small disparity in the overall rate of favorable outcomes between male and female groups. Demographic parity measures whether the probability of receiving a positive prediction is independent of group membership. A value close to zero suggests that the model produces nearly equal positive outcome rates across the two gender groups, regardless of the true labels. In practical terms, this value implies that the absolute difference in positive prediction rates between males and females is approximately 1.83%, which is generally considered negligible in many applied fairness contexts. This result suggests that the model does not exhibit substantial selection bias with respect to gender at the level of marginal predictions.

In contrast, the EOD was measured as 0.141, indicating a more pronounced disparity when conditioning on the true outcome. Equalized odds evaluates whether a model’s error rates, true positive rates and false positive rates, are similar across protected groups. This value suggests that there is a non-trivial imbalance in predictive performance between male and female individuals. In particular, the model may be systematically more accurate for one gender than the other, either by exhibiting higher sensitivity (true positive rate) or lower false alarm rates (false positive rate) for one group. This form of disparity is especially important in decision-critical applications, as it implies unequal treatment in terms of prediction reliability rather than merely outcome frequency.

Overall, these results indicate that while the model achieves near parity in overall outcome allocation across genders, it fails to fully satisfy conditional fairness constraints captured by equalized odds. This discrepancy highlights a well-known trade-off in algorithmic fairness: achieving demographic parity does not necessarily guarantee equalized performance across groups.

3.4. Generative Algorithms

Synthetic data research has evolved substantially over the past decade, progressing from classical statistical approaches to advanced deep generative architectures. In a seminal contribution, Patki et al. [

20] introduced Synthetic Data Vault (SDV), one of the first general-purpose frameworks for generating high-fidelity synthetic tabular data. The SDV leverages probabilistic modeling and copula-based techniques to learn joint distributions from real datasets and to generate statistically consistent synthetic samples. Its modular architecture enables the synthesis of relational, sequential, and time-series data, making it highly adaptable across diverse domains such as finance, healthcare, and education. Beyond its technical contribution, the SDV established an open-source ecosystem for benchmarking data synthesizers and evaluating data fidelity, privacy, and machine learning utility. This framework has since become a cornerstone for research on synthetic data generation, providing both methodological rigor and practical accessibility for reproducible data science.

With the advent of deep generative models, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [

21] and Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) [

22,

23] brought transformative improvements in capturing complex data manifolds. Conditional variants such as CTGAN [

24] and TVAE [

25] enabled realistic synthesis of mixed-type tabular data. More recent developments, including PATE-GAN [

26] and diffusion-based frameworks [

13], incorporate explicit privacy mechanisms, adversarial fairness regularization, and enhanced sampling stability. While these advances have led to widespread adoption in fields such as healthcare and finance, systematic comparisons across different synthesizer types under educational data constraints remain scarce.

In this study, we employed the open-source SDV library to generate synthetic data. The SDV framework offers a suite of synthesizers, each designed to accommodate distinct data types and statistical characteristics. Below we provide a concise overview of the algorithms utilized.

3.4.1. Gaussian Copula

Gaussian Copula-based synthetic data generation relies on statistical dependence modeling through copula theory, where multivariate relationships are decoupled from marginal distributions and reconstructed using a Gaussian latent correlation structure [

27]. This approach enables the synthesis of tabular datasets with mixed data types by first transforming features into a continuous latent space, estimating a correlation matrix under the assumption of a multivariate normal copula, and subsequently sampling new synthetic observations that preserve pairwise dependencies while allowing flexible marginal distributions [

8]. In practical large-scale applications, the Gaussian Copula model has been integrated into the SDV framework, where it has demonstrated strong performance in maintaining correlation fidelity and statistical resemblance across real-world datasets while avoiding issues such as mode collapse that may arise in deep generative models [

20]. Empirical benchmarking studies further show that Gaussian Copula-based synthesis can achieve competitive utility for downstream predictive tasks in comparison to neural generative models, particularly in structured tabular domains where linear and monotonic dependencies dominate [

25].

In our experiments, we evaluated multiple candidate marginal distributions for each feature, including Gaussian, Beta, Truncated Gaussian, Uniform, Gamma, and Kernel Density Estimation. To model the joint dependencies among variables, the SDV framework employs a multivariate Gaussian Copula, which first transforms each column into a standard normal space using appropriate probability integral transforms and then estimates the inter-variable covariance structure within this latent domain. Once the copula-based dependence model is learned, synthetic samples are generated by drawing observations from the resulting multivariate distribution, followed by inverse transformation into the original feature domains. This procedure enables the synthesis of multiple realistic rows that preserve the statistical relationships captured in the original data, while maintaining flexibility in representing heterogeneous marginal distributions.

3.4.2. Conditional Tabular GAN (CTGAN)

The Conditional Tabular GAN (CTGAN) [

25] is a state-of-the-art deep generative modeling framework specifically designed to overcome the challenges of synthesizing high-quality tabular data, which typically exhibit heterogeneous feature types, non-Gaussian multimodal distributions, and class imbalance. CTGAN is built upon the Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) paradigm [

21,

28], where a generator network learns to replicate realistic samples by approximating the underlying joint data distribution, while a discriminator attempts to distinguish real samples from synthetic ones; both models are optimized concurrently in a minimax game. Unlike conventional GANs that assume continuous and unimodal distributions, CTGAN introduces mode-specific normalization for continuous features and employs a conditional generator based on training-by-sampling to ensure that imbalanced categorical values are adequately represented during training [

25]. Continuous attributes are encoded through a combination of per-mode one-hot encodings and normalized scalar values, while categorical attributes are sampled in a class-balanced manner so that minority categories are sufficiently modeled. During the inference phase, CTGAN reverses these transformations, restoring the original data space so that generated samples accurately reflect both marginal and joint feature distributions. Empirical studies demonstrate that CTGAN produces high-utility synthetic datasets suitable for downstream machine learning and privacy-preserving analytics, outperforming conventional probabilistic approaches, particularly when dealing with complex non-linear feature dependencies.

3.4.3. CopulaGAN

Copula-based Generative Adversarial Networks (CopulaGAN) constitute a prominent deep generative modeling approach for synthetic tabular data, designed to capture complex multivariate dependencies while effectively handling mixed numerical and categorical attributes. Building on classical copula theory for statistical dependency modeling [

27]. CopulaGAN integrates copula-based sampling into the GAN training pipeline to more accurately preserve joint distributions and nonlinear correlations within high-dimensional tabular datasets [

25]. The model was introduced as part of the SDV framework, where empirical evaluations demonstrated that combining copula-driven transformations with adversarial learning improves fidelity and diversity over baseline tabular synthesis methods, particularly when variables exhibit non-Gaussian distributions or heterogeneous marginal behaviors [

20,

25]. Results further indicate that CopulaGAN achieves competitive predictive utility in downstream machine-learning tasks while reducing overfitting effects commonly observed in purely GAN-based tabular generators [

24], making it a robust candidate for privacy-preserving data augmentation in domains such as education, finance, and healthcare where relational structure and conditional distributions must be accurately retained.

3.4.4. Tabular Variational Auto Encoders (TVAE)

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) [

22] have emerged as a widely adopted deep generative modeling approach for synthetic data generation due to their ability to learn continuous latent representations and produce statistically realistic samples while maintaining computational efficiency and training stability [

23]. Unlike adversarial models, VAEs optimize a tractable variational lower bound, enabling more reliable convergence and controllable generation through latent-space manipulation [

29]. In the context of tabular data, Tabular Variational Autoencoders (TVAEs) [

25] extend the VAE framework by incorporating specialized encoding mechanisms for heterogeneous feature types, conditional sampling, and tailored likelihood functions that better capture discrete, categorical, and mixed data distributions commonly found in the educational domain. Empirical studies have demonstrated that TVAEs can achieve competitive performance in statistical fidelity and predictive utility when compared with GAN-based models, while generally offering lower mode collapse risk and improved stability during training [

25]. These strengths position TVAEs as a robust and practical generative solution for privacy-preserving data synthesis across sensitive, real-world applications.

3.5. Methodology

The present study aims to investigate the effectiveness of synthetic data generation within educational contexts, using real student datasets collected from multiple undergraduate courses. Specifically, we examine whether synthetic datasets can serve as reliable substitutes for real data when training ML models, and to what extent they can preserve predictive performance on real-world evaluation samples. To ensure a fair and systematic validation process, we adopted a three-fold cross-validation procedure in which the original dataset was partitioned into three stratified folds, maintaining the original class distribution.

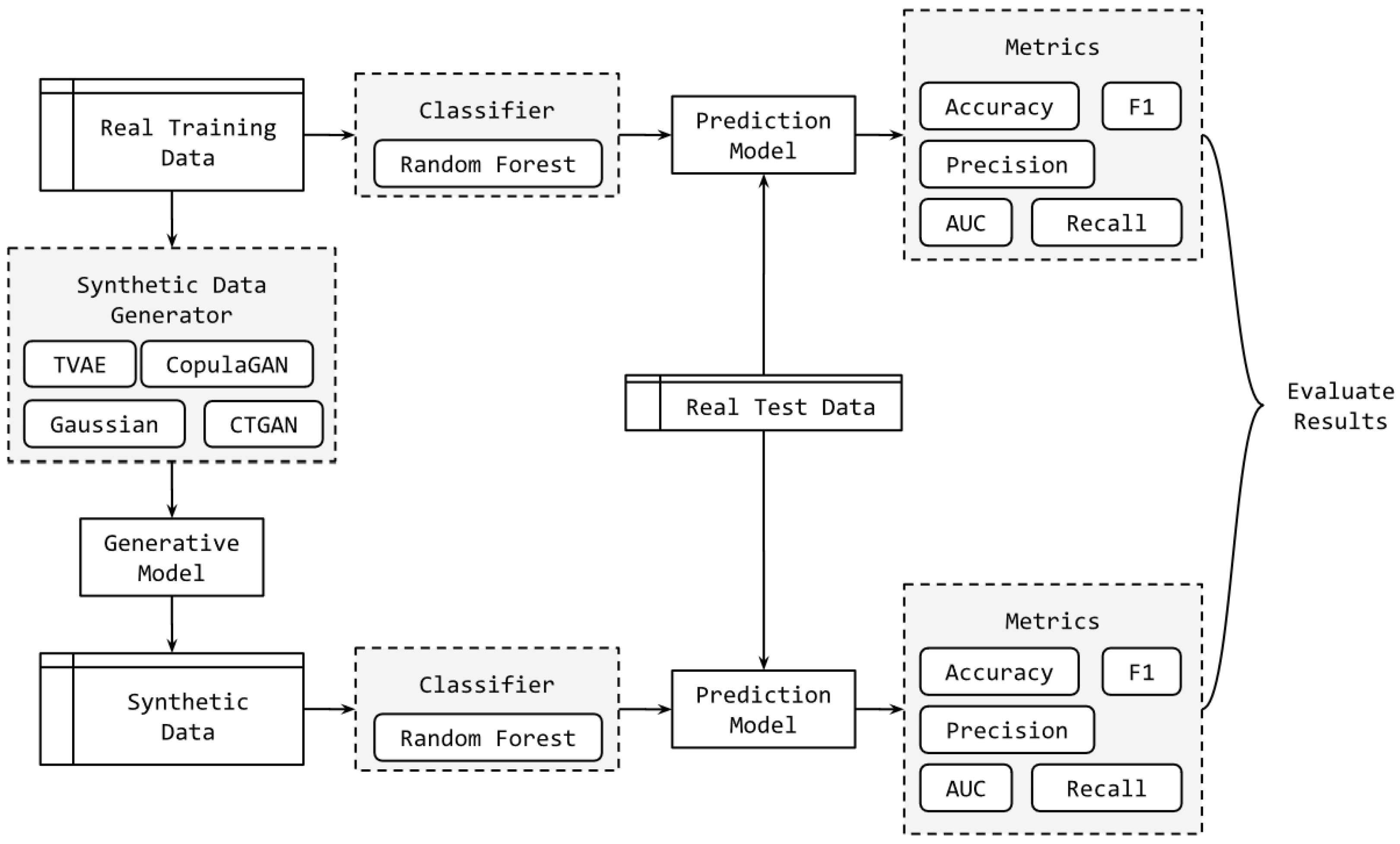

As illustrated in

Figure 2, for each cross-validation iteration, two parallel experimental streams were executed. In the first stream, the real training fold was used to train a Random Forest (RF) classifier, which served as the baseline predictive model. RF was selected due to its robustness, non-parametric nature, and strong performance on heterogeneous educational data. In the second stream, the same real training fold was used to train four distinct synthetic data generators: Gaussian Copula, CopulaGAN, CTGAN, and TVAE, covering both probabilistic modeling and deep generative learning paradigms. After model fitting, each generative model produced a synthetic dataset of equal size and schema to the original training fold. A separate RF classifier was then trained solely on each synthetic dataset, ensuring no leakage of real samples into synthetic-based model training.

Both the baseline model (trained on real data) and the synthetic-based models (trained on generated data) were evaluated exclusively on the held-out real test fold for each split, ensuring a strict assessment of predictive utility and generalization capability. Model performance was quantified using standard classification metrics, namely Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, and Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC), enabling an in-depth comparison across class balance, discrimination ability, and error trade-offs. By directly contrasting the real-trained and synthetic-trained models under identical conditions, the proposed methodology provides a rigorous analytical framework for determining whether synthetic student data can effectively replace real data in predictive EDM and LA tasks. The pseudo-code of the proposed method is presented in

Table 3.

3.6. Environment and Hyperparameters

All experiments were conducted using the SDV library (v1.32.0) in Python [

20]. The four generative models were carefully configured to ensure that the synthetic data remained within the observed ranges of the original datasets, preserving realistic distributions and feature constraints. TVAE and GAN-based models were selected to represent complementary approaches to tabular data synthesis, probabilistic modeling and adversarial learning, respectively. This selection enables a systematic comparison of their ability to balance the key evaluation criteria of this study: predictive utility and privacy preservation.

The values of the hyperparameters reported in

Table 4 were determined by considering commonly adopted configurations from prior studies, combined with limited validation on the actual dataset. For all models, training was conducted for 500 epochs, allowing the generators to capture complex feature dependencies while mitigating the risk of overfitting. The batch size was fixed at 32 as a practical compromise between training stability and computational efficiency. A broader hyperparameter search was not considered, as the primary focus of this work is the comparative evaluation of synthesis methods rather than extensive model optimization. Other relevant hyperparameters and configuration details are summarized in

Table 4.

Overall, this experimental setup enables a comprehensive assessment of each model’s effectiveness in generating high-quality, privacy-aware synthetic educational data that can support reproducible and ethically responsible EDM and LA research.

4. Results

Evaluating generative models remains a non-trivial task, particularly when the goal is to assess the practical utility of the synthetic data they produce. In this study, we adopt an indirect evaluation strategy: instead of measuring similarity metrics alone, we examine whether ML models trained exclusively on synthetic data can accurately predict student performance (pass/fail) on real, held-out observations. This approach provides an application-oriented assessment of data quality, reflecting the extent to which the synthetic samples preserve the predictive structure of the original dataset.

To establish a performance reference point, we first conducted a series of baseline experiments using a Random Forest classifier trained on the real dataset. These baseline scores represent an approximate upper bound on the predictive performance we can reasonably expect when training on synthetic data. The averaged results, reported in

Table 5, demonstrate consistently strong performance across all evaluation metrics. This indicates not only that the Random Forest model is well-suited for the task, but also that the real dataset contains substantial and reliable predictive signal regarding student success.

We subsequently trained Random Forest models on the synthetic datasets produced by each of the four generative synthesizers and evaluated their performance on the same real test folds used in the baseline experiments. The results, summarized in

Table 6, reveal that all models achieve consistently strong performance across the full set of evaluation metrics, with only moderate degradation relative to the models trained on the original data. A more detailed examination of the performance across the five evaluation metrics is presented below providing additional insight into the relative strengths and limitations of each synthesizer.

CTGAN achieves solid overall performance, with accuracy (0.7329) and F1-score (0.7827) that are competitive with the other methods. Its precision (0.8172) is particularly strong, suggesting that the synthetic data generated by CTGAN enable the model to correctly identify successful students with relatively few false positives. However, its recall (0.7893) and especially its AUC (0.7057) are somewhat lower than those of the other synthesizers, indicating that CTGAN may not fully capture the underlying class-separation structure of the real dataset.

Gaussian Copula-based synthesis demonstrates more balanced and consistently high performance across all metrics. It attains the second-highest accuracy (0.7623), the second highest F1-score (0.8212), and competitive precision (0.8174) and recall (0.8290). Its AUC score (0.7303) is also among the strongest. These results suggest that Gaussian Copula models are adept at capturing global dependency patterns and reproducing the statistical relationships that drive predictive performance in the real data.

CopulaGAN shows a mixed profile: while its accuracy (0.7330) and precision (0.7759) are modest relative to the other methods, it achieves the highest recall (0.8615) of all synthesizers. This indicates that models trained on CopulaGAN data are particularly effective at identifying at-risk students, albeit at the cost of a larger number of false positives. The comparatively lower AUC score (0.6713) further suggests that CopulaGAN’s synthetic data may exaggerate certain class-conditional patterns, improving sensitivity while reducing overall discriminative balance.

TVAE yields the strongest overall performance among the four synthesizers, with the highest accuracy (0.7697) and F1-score (0.8283), and strong precision (0.8151) and recall (0.85). Its AUC value (0.7312) also places it among the best-performing models. These results highlight TVAE’s ability to capture complex nonlinear relationships within the dataset, providing synthetic samples that align closely with the real distribution and support robust predictive modeling.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that all four synthesizers are capable of generating synthetic educational datasets that preserve essential predictive patterns. While their performance profiles differ, some favoring precision, others recall, and others balanced discrimination, the overall results provide strong evidence that generative modeling can serve as a viable tool for privacy-preserving educational data without severely compromising predictive utility.

To further substantiate the comparative performance patterns observed in

Table 6, we conducted a Friedman Aligned Ranks non-parametric test (

) for each evaluation metric. The results, summarized in

Table 7, corroborate the descriptive findings by statistically validating that the four synthesizers differ significantly across all metrics. In every case, the

p-value falls below the significance threshold, confirming that the observed differences in predictive performance are unlikely to be due to random variation. A closer inspection of the aligned ranks reveals a consistent performance hierarchy that aligns closely with the empirical results previously discussed:

TVAE achieves the best rank for three out of the five metrics (Accuracy, F1-score, and AUC) demonstrating its overall dominance in generating synthetic data that effectively preserve class-discriminative structure. Its second-best position in Recall further strengthens this conclusion, indicating that TVAE produces synthetic datasets with strong generalization capabilities across evaluation criteria.

Gaussian Copula exhibits the second-best overall behavior. It ranks second in Accuracy, F1-score, and AUC, and although it falls to third place in Recall, it attains the best rank in Precision. This performance pattern reinforces the earlier observation that Gaussian Copula synthesizers are particularly effective in capturing global statistical dependencies, yielding synthetic data that support balanced and reliable predictive performance.

CTGAN consistently occupies third place in most metrics (Accuracy, F1-score, and AUC), while achieving second place in Precision. These findings mirror those of

Table 6, where CTGAN displayed strong precision but comparatively weaker recall and AUC. This suggests that CTGAN tends to generate synthetic data that favor conservative decision boundaries, enabling precise identification of positive cases while sacrificing broader sensitivity.

CopulaGAN, although achieving the top rank in Recall, consistent with its high empirical recall in

Table 6, exhibits the lowest rank across the remaining four metrics. This reflects its tendency to overemphasize minority-class detection, leading to higher sensitivity at the expense of overall discriminative balance, as evidenced by its lower AUC and precision.

Taken together, the Friedman test results provide a rigorous statistical validation of the performance landscape mapped out by the descriptive metrics. TVAE emerges as the most robust and consistently high-performing synthesizer, followed by Gaussian Copula; CTGAN demonstrates moderate and specialized strengths, while CopulaGAN emphasizes recall but struggles with overall balance. These complementary quantitative and statistical evaluations strengthen the conclusion that TVAE and Gaussian Copula offer the most reliable synthetic data for downstream educational LA.

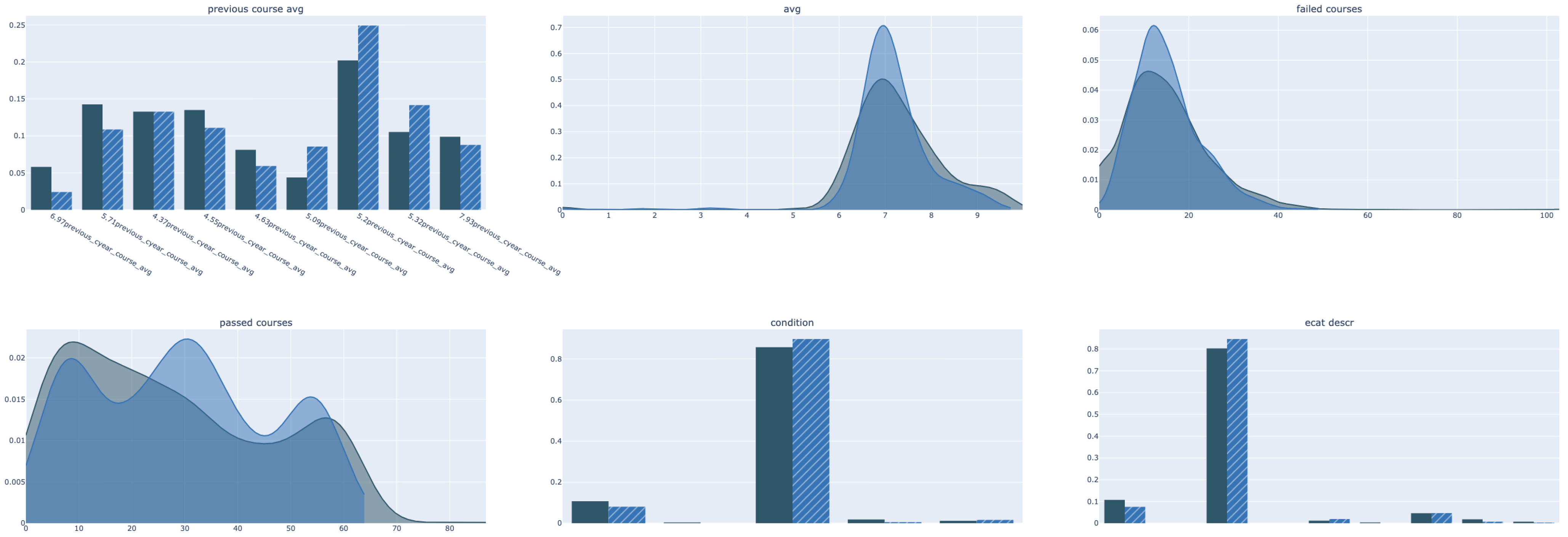

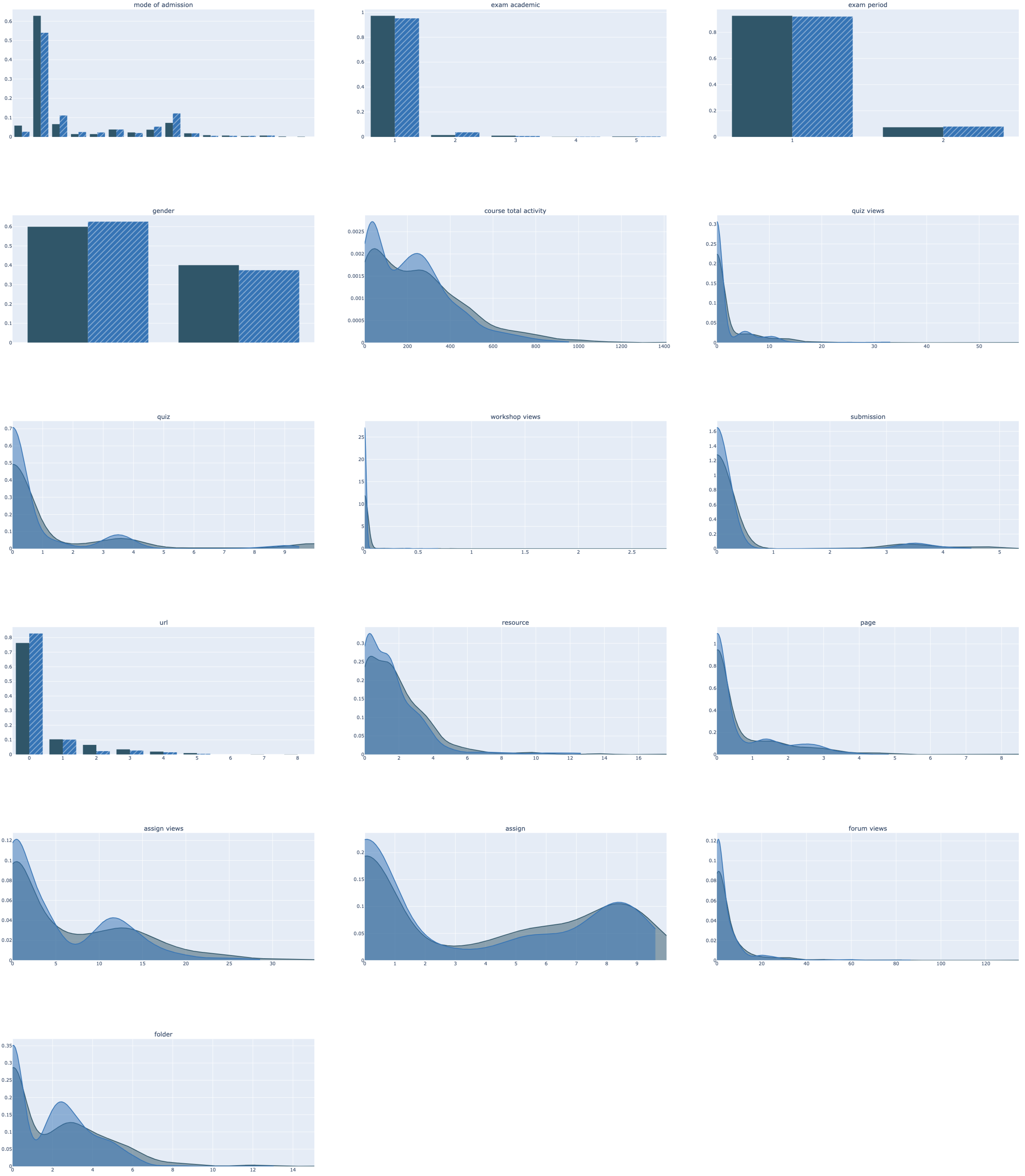

Finally, to complement the quantitative evaluation, we examined the distributional similarity between real and synthetic data through a feature-wise visualization, shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. For this purpose, we randomly selected one synthetic dataset generated by a TVAE model during the iterative training process described in

Table 3. The figure presents the empirical distributions of each feature for both real and synthetic samples. The close alignment observed across features provides additional qualitative evidence that the TVAE synthesizer is capable of capturing key statistical properties of the real educational dataset, thereby reinforcing the validity of the synthetic data for downstream analytical tasks.

5. Discussion

Our findings confirm that high-quality synthetic data can serve as a practical and effective alternative to real educational datasets while maintaining comparable predictive utility. Across the four synthesizers evaluated, models trained on synthetic data retained approximately 96–98% of the predictive accuracy achieved with real data. This result aligns closely with recent empirical evidence demonstrating that machine learning models trained on high-fidelity synthetic educational data can approach the performance of their real-data counterparts [

9,

11,

13]. Among the tested methods, the TVAE synthesizer consistently produced the most realistic samples and best preserved the statistical dependencies between features and learning outcomes. Its capacity to jointly model mixed-type attributes renders it particularly well suited for tabular educational datasets, which typically integrate demographic variables, course engagement indicators, and academic performance metrics.

5.1. Interpretation of Results

The results demonstrate that, within structured educational datasets, deep generative models are capable of capturing latent feature dependencies that are essential for predictive learning analytics. The modest decline in performance (approximately 2–4%) relative to models trained on real data reflects the well-documented trade-off between privacy and data fidelity. This pattern is consistent with observations by Iloh et al. [

9], who found that GAN-based synthesizers such as CTGAN can retain over 90% of the predictive utility of real datasets while substantially mitigating privacy risks. Our results reinforce this trend, indicating that both statistical and deep generative synthesizers can approximate real educational data sufficiently for exploratory analysis and predictive modeling within EDM.

Moreover, the comparative performance across synthesizers suggests that the optimal choice depends on the intended analytical task. Statistical methods such as the Gaussian Copula tend to preserve marginal feature distributions with high fidelity, making them suitable for descriptive analytics or visual inspection. In contrast, deep generative methods such as TVAE and CTGAN more effectively capture complex multivariate dependencies, thereby yielding synthetic samples better suited for downstream predictive modeling.

5.2. Privacy and Ethical Considerations

While synthetic data naturally reduce the risk of exposing sensitive or personally identifiable student information, privacy cannot be presumed by default. As emphasized by Liu et al. [

11], generative models may inadvertently memorize parts of the training data unless explicit privacy safeguards are adopted. Future research should therefore incorporate formal privacy mechanisms, such as differential privacy, or utilize post-generation auditing techniques, including membership-inference tests, to quantify residual privacy risks in educational contexts.

Fairness considerations are equally important. Kesgin’s FairSYN-Edu framework illustrates that integrating fairness constraints and differentially private optimization into synthetic data generation can substantially reduce demographic disparities while maintaining analytical utility. Although fairness was not explicitly evaluated in our study, the demographic attributes present in educational datasets (e.g., gender, admission category) may influence both predictive outcomes and synthesis behavior. Incorporating fairness-aware synthesis, through adversarial debiasing, constraint-based optimization, or diffusion-driven balancing, represents a crucial next step toward equitable and responsible educational LA.

5.3. Reproducibility and Benchmarking

A major challenge in synthetic data research remains the lack of standardized and reproducible evaluation practices. Both Iloh et al. [

9] and Kesgin [

13] addressed this concern by releasing open-source pipelines and benchmark datasets, thereby establishing transparent reference points for comparing synthesizers. Our work contributes to this emerging culture of reproducibility by formalizing the entire synthesis and evaluation workflow, including data partitioning, model training, and cross-validation metrics. Establishing shared benchmarks for educational data synthesis would greatly facilitate systematic comparisons across institutions and datasets, accelerating methodological progress in the field.

5.4. Implications for Educational Data Mining

The capacity to generate realistic yet privacy-preserving synthetic educational data carries several important implications for EDM. First, it enables researchers to design, test, and refine predictive models, such as dropout detection systems, early-warning algorithms, or adaptive learning interventions, without accessing identifiable student information. Second, synthetic data support cross-institutional collaboration by allowing models and evaluation pipelines to be shared without violating privacy regulations such as GDPR. Third, synthetic datasets can drive pedagogical and technological innovation, enabling educators, data scientists, and system developers to simulate learning scenarios or stress-test analytics pipelines in risk-free environments.

Collectively, the consistency between our findings and those reported in recent literature suggests that synthetic data generation has evolved from a niche methodological approach into a mature and viable tool for LA. Realizing its full potential, however, will require balancing three interconnected goals: (i) ensuring high fidelity and analytical utility, (ii) maintaining fairness and representational equity, and (iii) enforcing robust, quantifiable privacy guarantees.

5.5. Limitations and Future Directions

Although the results of this study are promising, several limitations warrant consideration.

First, the data used in this analysis comes from the academic period of 2017–2019, which corresponds to the first phase of the GDPR influence, before it was further reinforced. Even though GDPR became active in 2018, its application in higher educational institutions was gradual, leading to stricter policies on the use of student performance data for analysis purposes in later academic years. Thus, data could only be extracted from this period, while access to more recent data was denied, despite being anonymous. This is a reflection of the current situation, as well as pointing to the need for the use of synthetic data in facilitating analysis development, as access to educational data is set to become more restricted.

In addition, the dataset was limited to six undergraduate courses from a single institution, which restricts the generalizability of the findings. Future research should therefore examine larger, multi-institutional datasets that reflect a broader spectrum of learning environments and pedagogical contexts.

Notably, another limitation of the research is that there is no direct evaluation of the fairness of the synthetic datasets produced. While the dataset includes demographics such as gender and admission type, there is no evaluation of whether the generation of synthetic datasets can potentially exacerbate any issues of disparity that may exist in the original dataset.

Furthermore, while our analysis focused on fidelity and predictive utility, it did not include explicit measurements of privacy or fairness. In line with recent advances [

10,

13], future work should incorporate quantitative privacy assessments, such as differential privacy

-bounds and membership inference robustness, as well as fairness evaluations using metrics like demographic parity or equalized odds.

Finally, our experiments focused on tabular data. Extending these methods to multimodal educational data, such as text (e.g., discussion forums), behavioral traces (e.g., clickstream logs), or temporal learning sequences, would enable a more comprehensive evaluation of generative approaches. Hybrid architectures, including diffusion-based and transformer-based synthesizers, hold particular promise for capturing the richer feature structures present in such data.

Future work should extend the present study along several dimensions. Technically, hybrid generative frameworks, such as diffusion-based synthesizers combined with differential privacy, as explored in [

13], should be evaluated on larger and more diverse datasets. Methodologically, integrating explainable AI techniques could help clarify how well synthetic features capture meaningful pedagogical constructs. Finally, establishing standardized evaluation metrics and shared benchmarks, such as SYNTHLA-EDU [

9], will enable longitudinal and cross-institutional comparisons of privacy–utility–fairness trade-offs.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the effectiveness of state-of-the-art synthetic data generation techniques for machine learning tasks in educational settings. Using real data drawn from six undergraduate courses, we evaluated four widely used synthesizers, Gaussian Copula, CTGAN, CopulaGAN, and TVAE, by training Random Forest classifiers on synthetic datasets and assessing their generalization performance on real held-out test data.

Our results show that models trained on synthetic data achieve predictive performance 96–98% of original data accuracy. Among the tested approaches, TVAE demonstrates the most consistent and robust performance across metrics, indicating its strong ability to capture complex feature dependencies relevant to student performance prediction. These findings confirm that high-quality synthetic data can closely approximate the statistical characteristics and predictive utility of real educational datasets.

The results are consistent with prior research emphasizing the potential of synthetic data to balance utility and privacy in educational contexts. In particular, Kesgin’s diffusion-based synthesis [

13] highlights promising directions for fairness-aware and privacy-preserving generative modeling, offering a complementary perspective to our findings.

From a practical standpoint, synthetic data provides an ethically responsible avenue for developing, validating, and deploying predictive models without compromising student privacy or violating regulatory constraints. It further promotes reproducible research and supports fair model evaluation by enabling broader access to representative datasets in EDM.

This study deliberately places the use of synthetic data within the context of being complementary, rather than alternative, to real-world student outcomes. The findings of this study show that, within controlled environments, there appears to be some useful predictive role for synthetic data, while also respecting that any kind of meaningful interpretation of learning or educational outcomes must be based on real-world data. This study hopes to help maintain the appropriate and correct role of synthetic data within the process of educational data mining by avoiding any kind of overextension of the capabilities of that role.

More recent approaches to synthetic data creation have also considered exploring hybrid, diffusion-based, and LLM-enriched solutions, especially within domains where notions of fairness and privacy remain very important. Diffusion-based approaches and fair synthetics (e.g., FairSYN-Edu) represent some promising efforts at modeling complex data distributions while also respecting explicit notions of bias mitigation and attribute-level control. Similarly, LLM-enriched approaches extend the process of synthetic data creation to more complex, semi-structured education domains, but correspondingly also represent a design paradigm where increased model expressiveness is often accompanied by decreased transparency. While these represent important and very actively explored lines of ongoing and future research, they also often tend to present a high computationally demanding barrier, requiring task-specific design choices and extensive tuning. By contrast, this particular paper focuses on established, very popular choices of existing generative models, strictly aiming at a reproducible, highly transparent approach to evaluating utility preservation within education data. A comparison with diffusion-based, possibly hybrid approaches certainly represents a very interesting path for a future, follow-up exploration.

At the same time, the study also has its limitations. The privacy issue is considered a driving force but is not treated as a property that is formally guaranteed. Neither differential privacy measures nor adversarial tests are claimed. The analysis scope can also be considered limited by the choice of the binary pass/fail outcome measure, along with the choice of a single baseline model. But even with its limitations, the current effort can be seen as a transparent analysis within the realities of the current day.