4.1. Dataset

In 2008, for a group of 26 countries worldwide—including Spain—and using 2006 as the reference year, surveys were initiated following guidelines set by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, and Eurostat (the Statistical Office of the European Union). The objective was to gather more detailed information on individuals holding a PhD (doctorate) degree. Most of the pioneering countries were members of the European Union, although other OECD members such as the United States and Australia also participated.

In Spain, the National Institute of Statistics (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, INE) led the effort to carry out this new statistical operation, with the aim of ensuring continuity in the availability of information in this field. As a result, the so-called “Survey on Human Resources in Science and Technology” was established as part of the broader statistical program on science and technology coordinated by Eurostat. The importance of this type of data collection is reflected in European Regulation 753/2004 on Science and Technology, which mandates the production of statistics on human resources in science and technology.

The CDH (Careers of Doctorate Holders) surveys aim to measure specific demographic and employment-related aspects of the doctoral population, such as research involvement, professional activity, job satisfaction, international mobility, and income levels. In Spain, the study focused on all doctorate holders residing in the country who were under 70 years of age and obtained their degree between 1990 and 2006 from a Spanish university (public or private). The sampling frame was a directory of doctorate holders provided by the University Council to INE. This register included all individuals who had defended a doctoral thesis at a Spanish university, based on electronic databases, comprising approximately 80,000 individuals.

According to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED-97), doctorate holders correspond to level 6, which includes tertiary programs that lead to advanced research qualifications. These programs are devoted to original research and advanced study and are not based solely on coursework.

Regarding the sampling design, a representative sample was selected for each region at the NUTS-2 level. The NUTS (Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics) classification is a hierarchical system used to divide the economic territory of the European Union (see Eurostat

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/nuts (accessed on 1 December 2024)). Sampling was performed independently within each region using equal-probability systematic sampling with a random start. A total of 17,000 doctorate holders were selected. Half of the sample was distributed uniformly across regions, and the remaining 50% was allocated proportionally to the number of doctorate holders residing in each region.

INE used a questionnaire harmonized at the European level, structured in several modules. The questionnaire can be accessed on the INE website (INE

https://www.ine.es/metodologia/t14/t1430225_cues.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024)). The overall national response rate was 72% of the initially selected sample. Data collection took place in 2006.

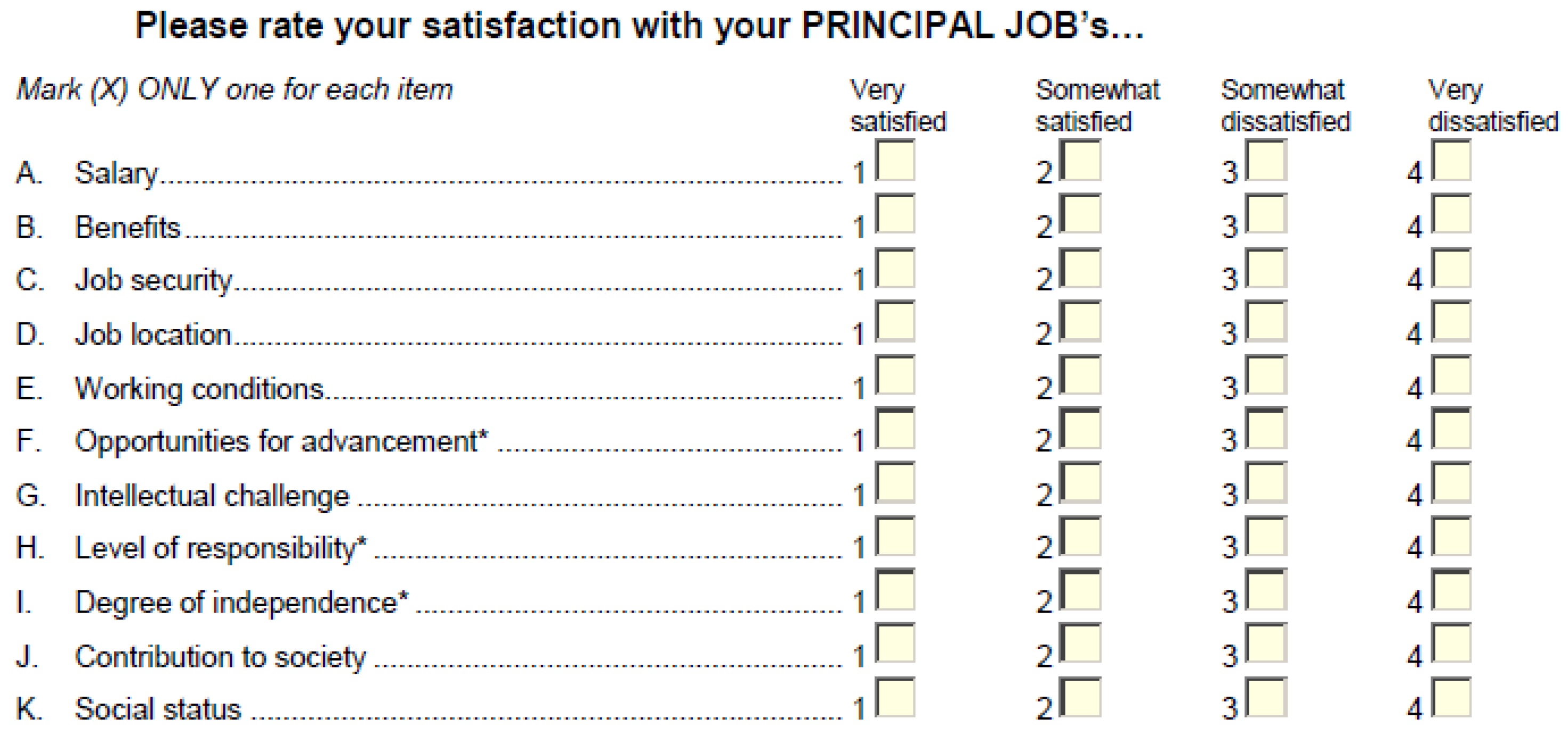

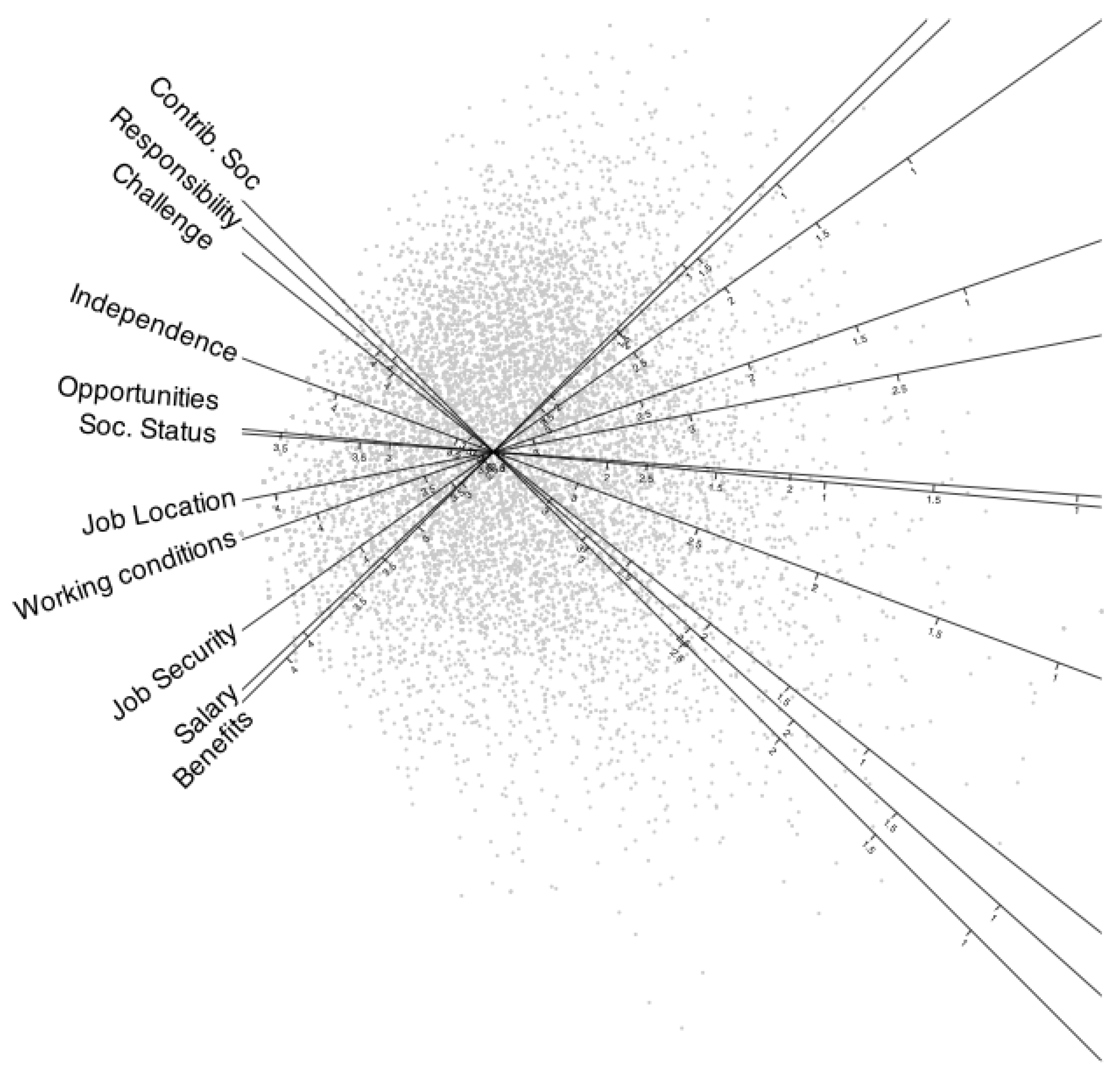

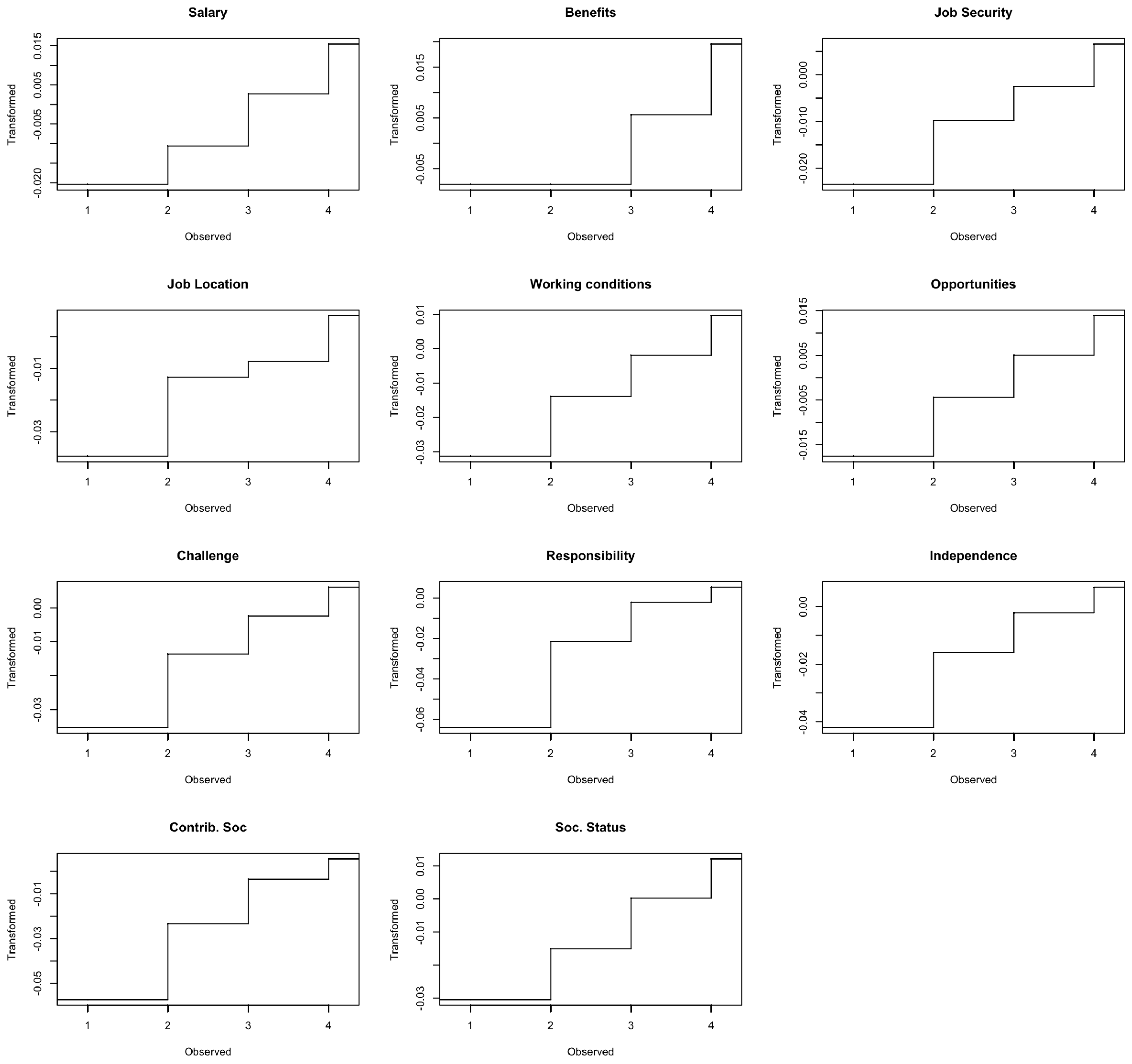

For this study, we use the responses of 12,193 doctorate holders in Spain. Our analysis focuses on Module C (Employment Situation), specifically on subsection C.6.4, which explores the level of satisfaction of doctorate holders with various aspects of their main job. Responses to this question are recorded using a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 4 (see

Figure 7).

Each item is treated as an ordinal variable, resulting in a total of 11 items or variables. For ease of interpretation, the responses to each question have been recoded so that higher values correspond to greater levels of satisfaction. The final coding scheme is as follows:

1—Very dissatisfied;

2—Somewhat dissatisfied;

3—Somewhat satisfied;

4—Very satisfied.

4.2. Results

Using the alternating algorithm to estimate the parameters of the two-dimensional model, we obtained the fit indices shown in

Table 1, the factor loadings and communalities in

Table 2, and the explained variances in

Table 3. To aid interpretation, the solution was rotated using a

varimax rotation.

To prevent potential separation issues during estimation, we employed a penalized version of the model, with a penalty parameter of 0.2, which is the default value in the package used.

All calculations and figures were produced using the MultBiplotR package ([

33]). In some figures, minor overlaps may appear, but these do not interfere with the interpretation. It should be kept in mind that this is an exploratory technique involving the simultaneous analysis of hundreds of objects, which naturally presents some visual complexity.

All variables exhibit an adequate fit to the model, as indicated by the different goodness-of-fit measures. The pseudo- values are generally high across items. For instance, the Nagelkerke pseudo- values range from 0.36 to 0.65, which most authors would consider reasonably strong. Similar values were observed for other pseudo- statistics.

In the context of ordinal logistic regression, pseudo-

statistics quantify the improvement in model fit relative to a null (intercept-only) model, rather than representing the proportion of variance explained, as in linear regression. These indices are derived from likelihood functions and should be interpreted as indicators of how much the inclusion of predictors improves the model’s explanatory power. A more detailed interpretation of the coefficients and fit indices can be found in [

47].

The percentages of correct classification for the cumulative probabilities are relatively high, ranging from 85.40% to 91.65%, with an overall rate of 88.03%. In contrast, the correct classification rates for the original ordinal responses are lower, ranging from 56.06% to 71.53%, with a global rate of 64.95%. This difference is expected, given that the model was optimized for the cumulative distributions rather than for the original ordinal values.

The Kappa coefficients are moderate to low, likely due to the same reason—that the model optimization targets the cumulative probabilities rather than the categorical responses. Nonetheless, all of these fit indices serve primarily as indicators of which variables align more strongly with the latent dimensions, that is, which variables exhibit a better fit to the model.

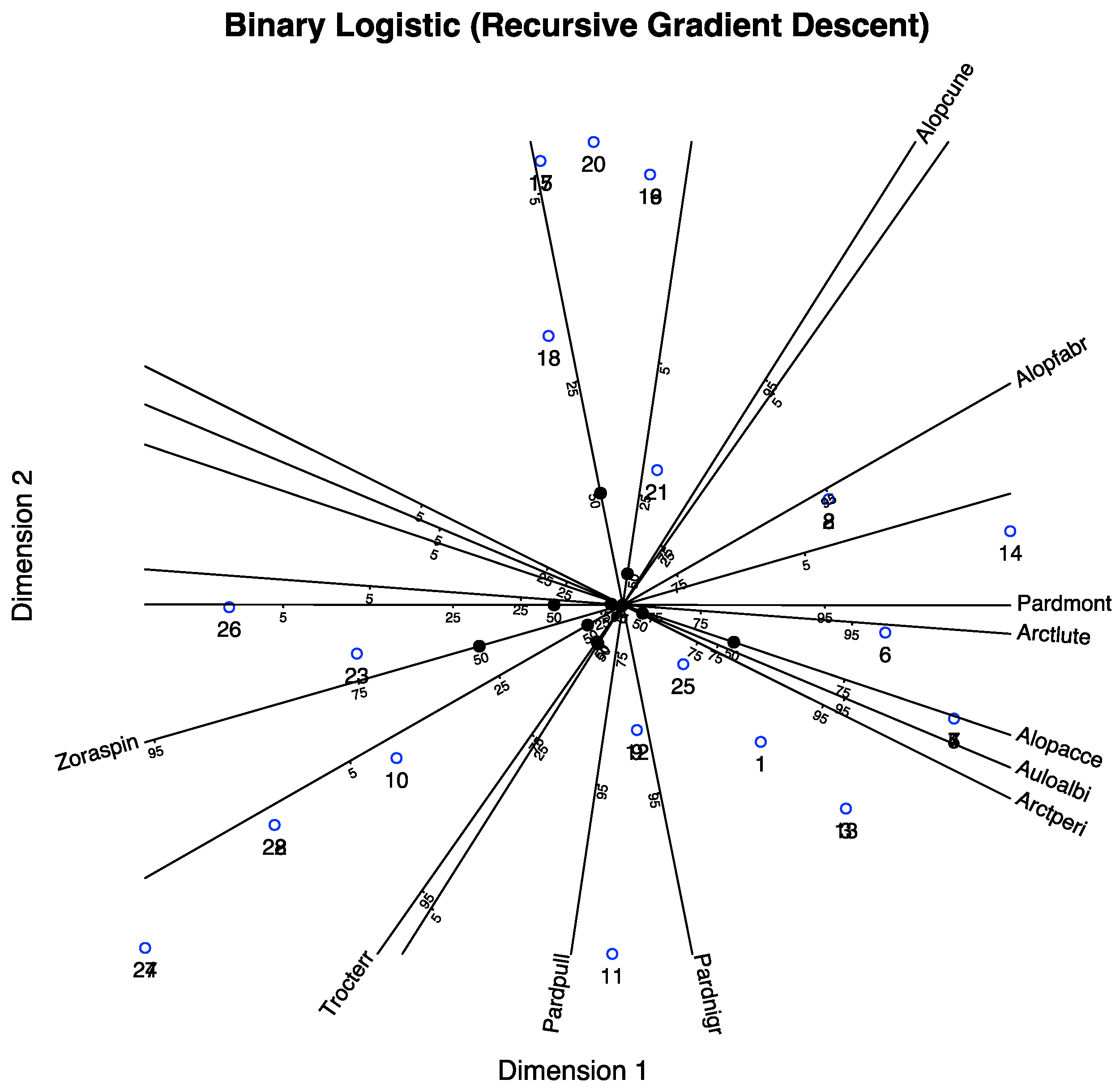

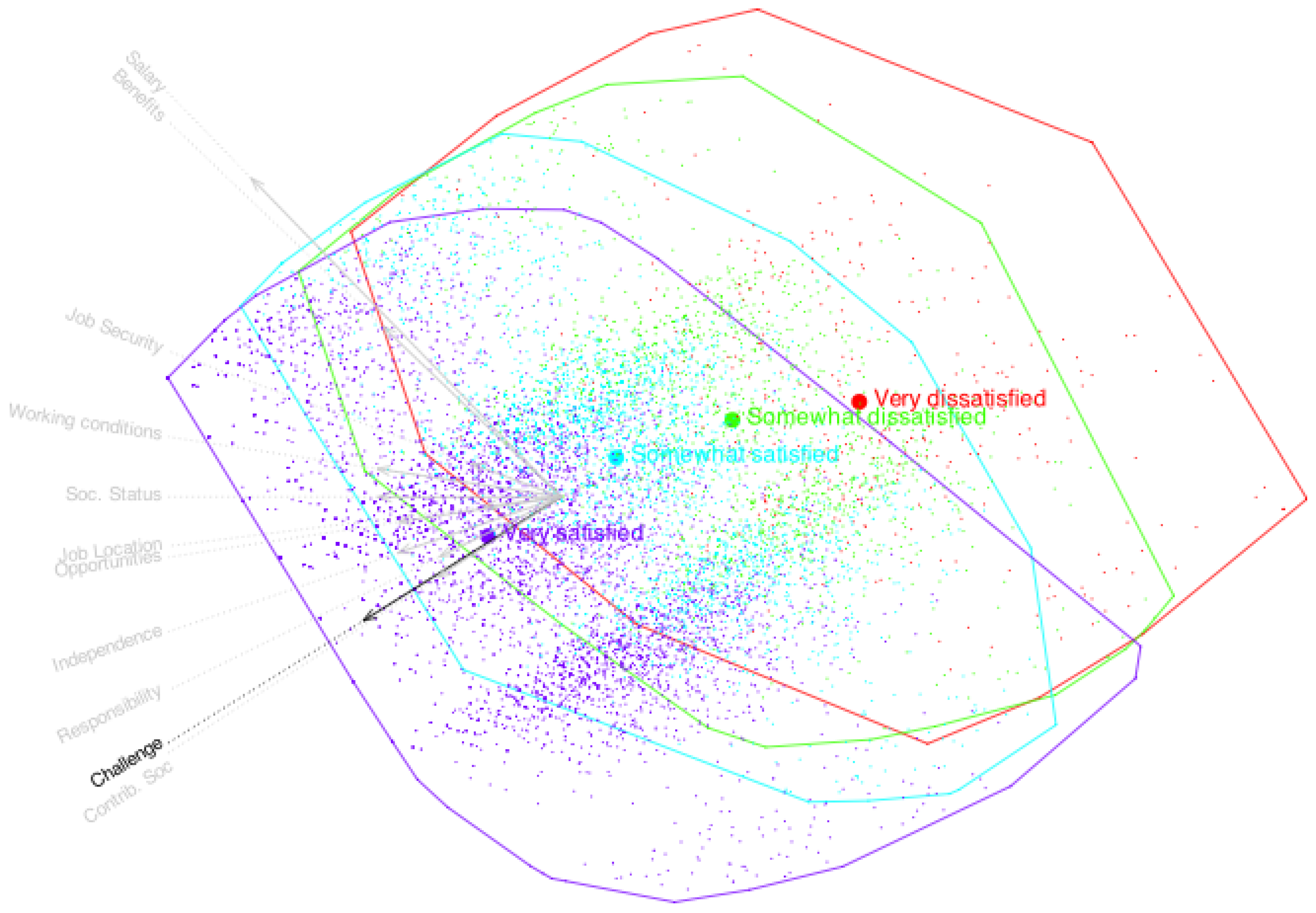

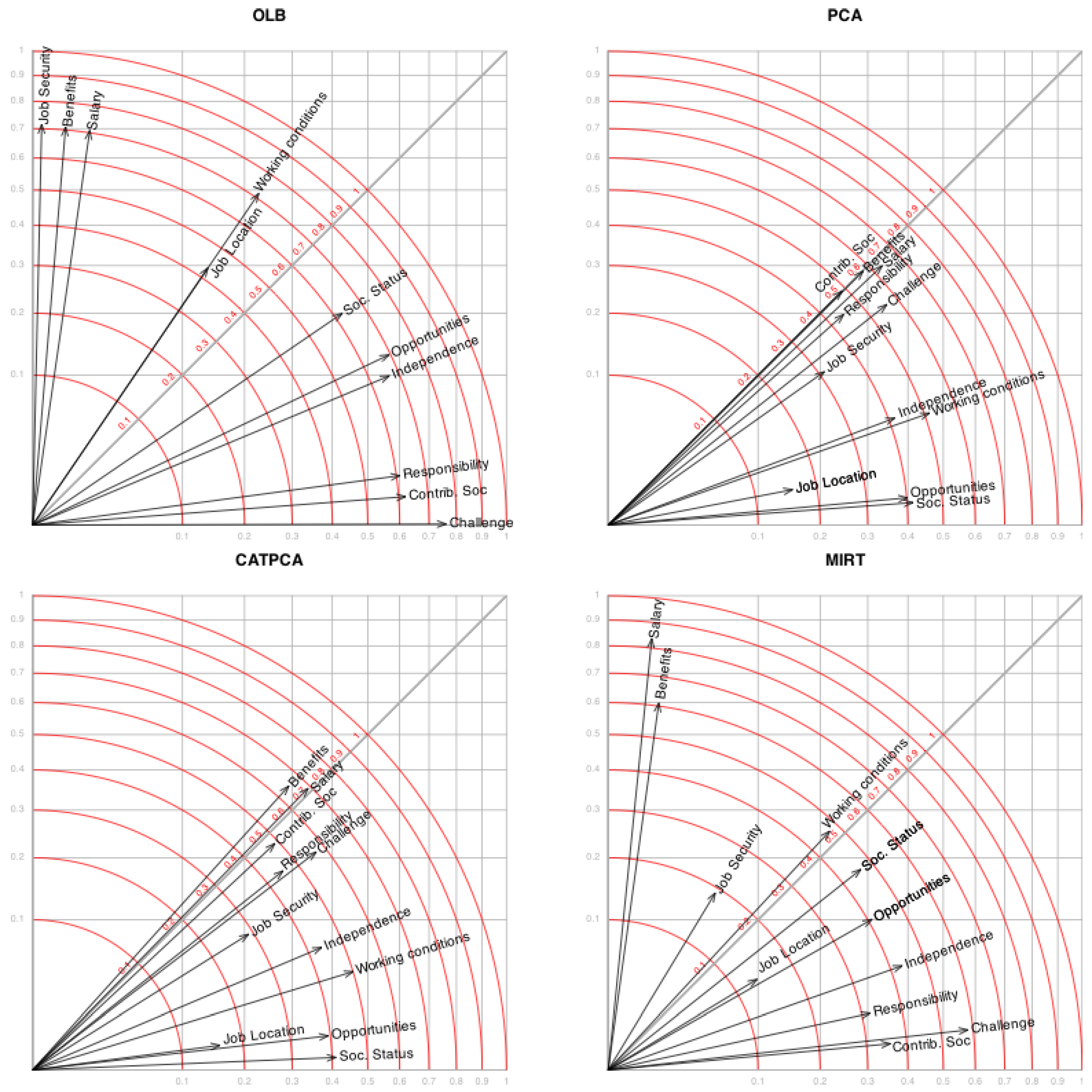

Analyzing the interpretation of the two extracted dimensions using their factor loadings, we observe that the first dimension exhibits higher loadings for the variables opportunities for advancement, degree of independence, intellectual challenge, level of responsibility, and contribution to society—all features typically associated with intellectual satisfaction.

The second dimension shows higher loadings for salary, benefits, job security, and working conditions, which are related to economic and work-related satisfaction. These results suggest the presence of two primary and nearly independent factors: one associated with intellectual aspects of the job, and the other with employment conditions.

The variables

job location and

social status exhibit similar loadings on both factors, indicating that they are associated with both dimensions. The angle between the vectors representing the variables that define each factor is close to

, which implies that satisfaction with income and work conditions is largely uncorrelated with intellectual satisfaction. This pattern has also been observed in other European countries, such as Austria [

48].

The variance explained by two factors is 65.94%, as shown in

Table 3.

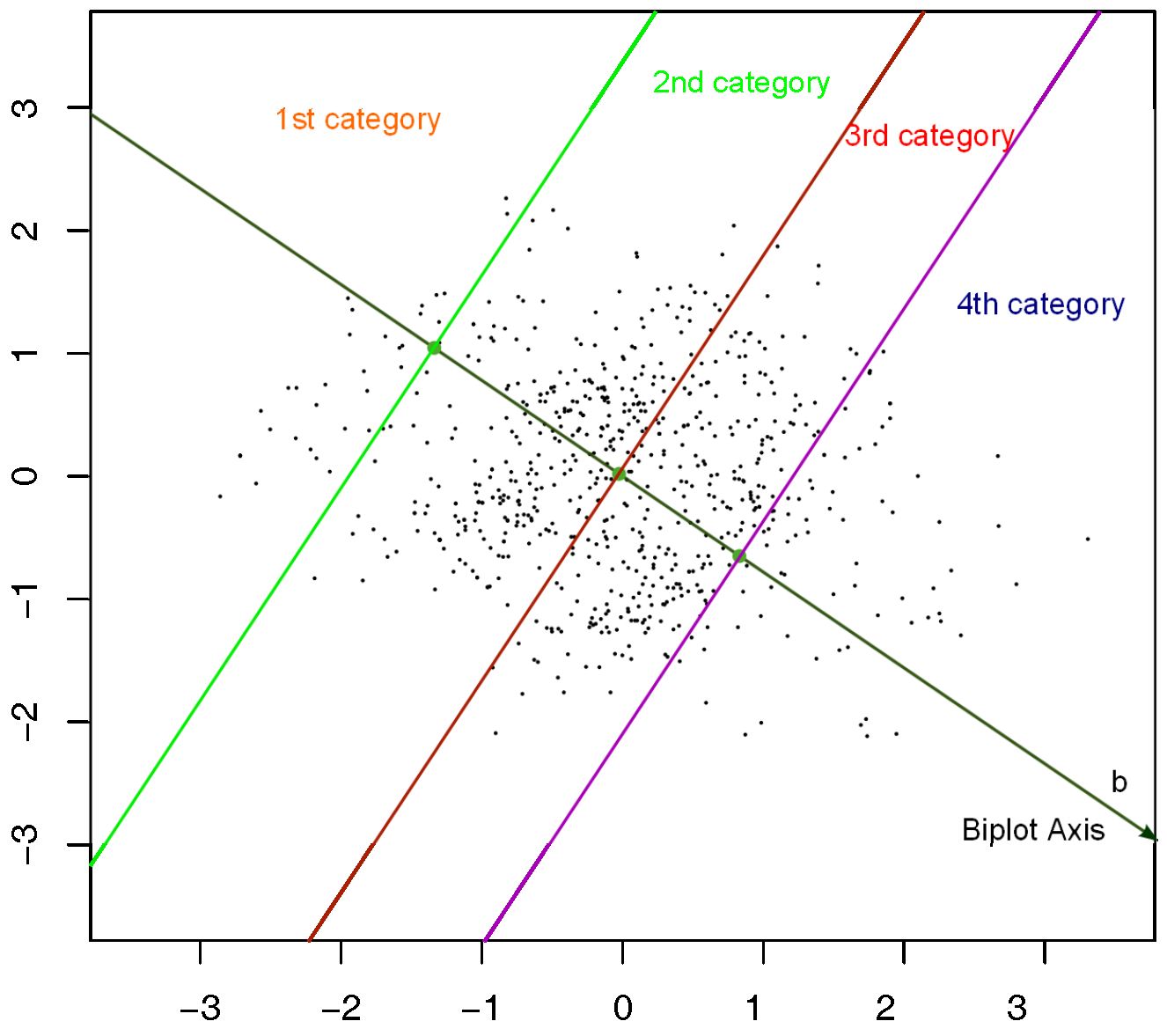

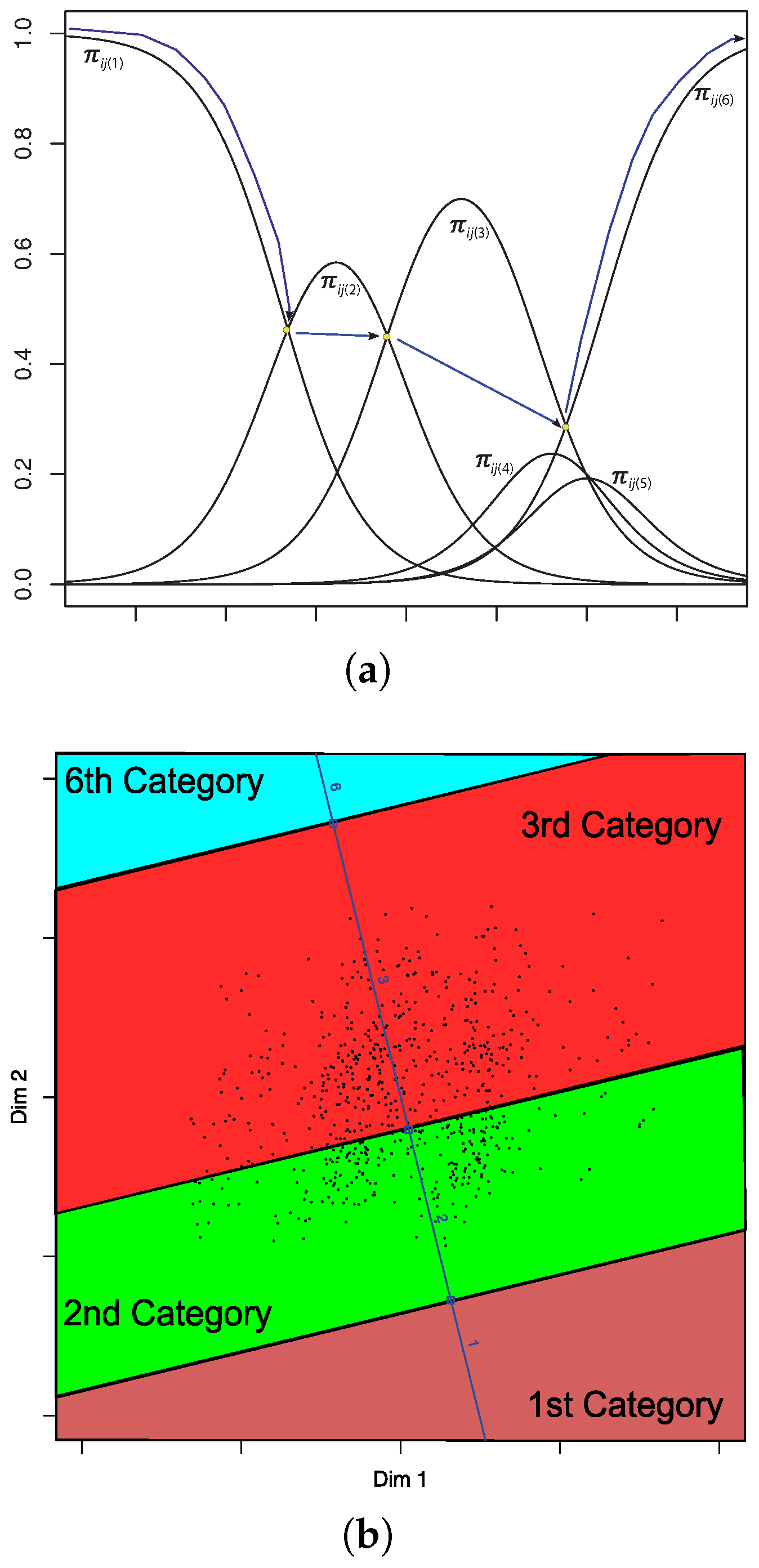

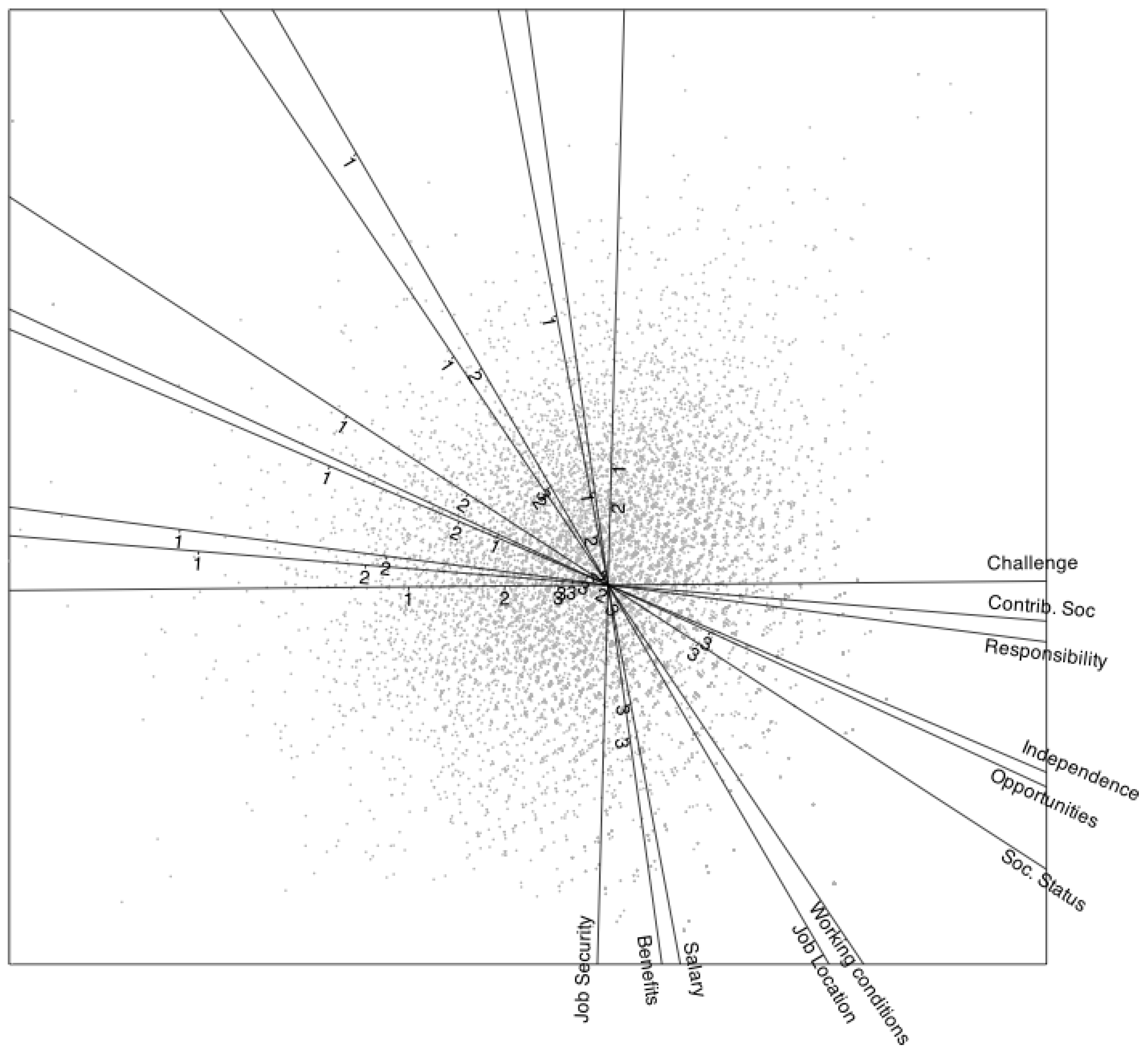

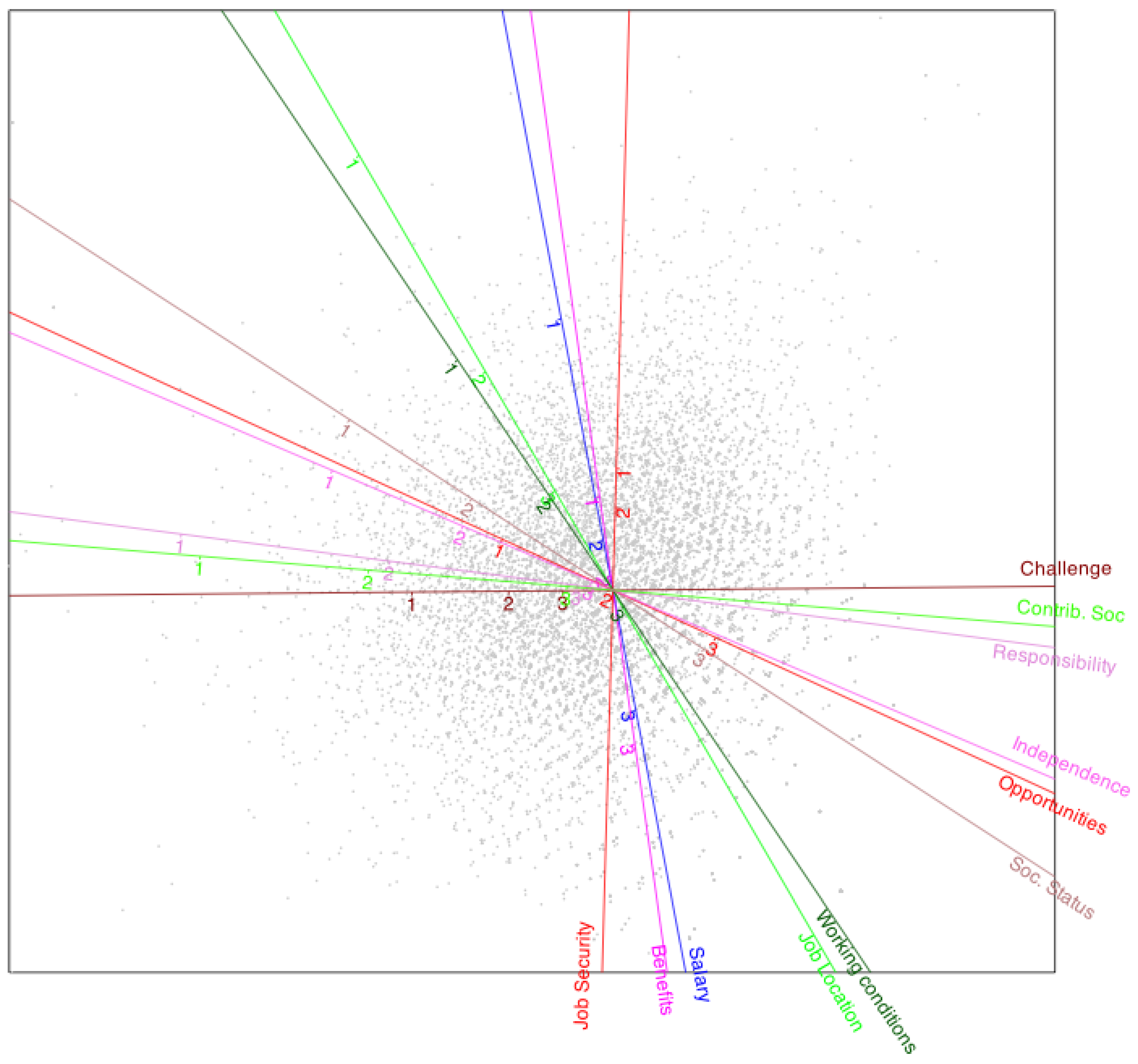

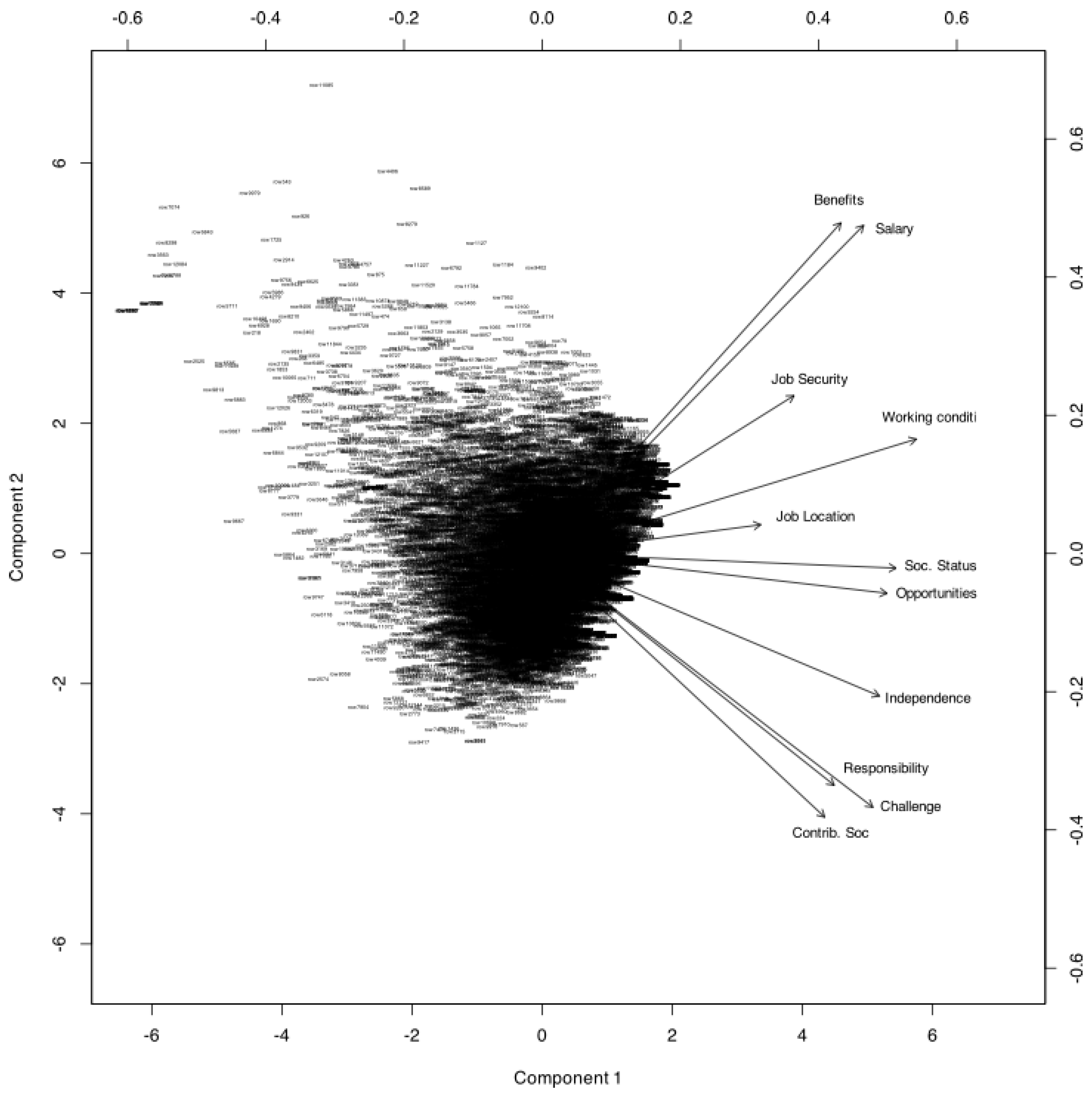

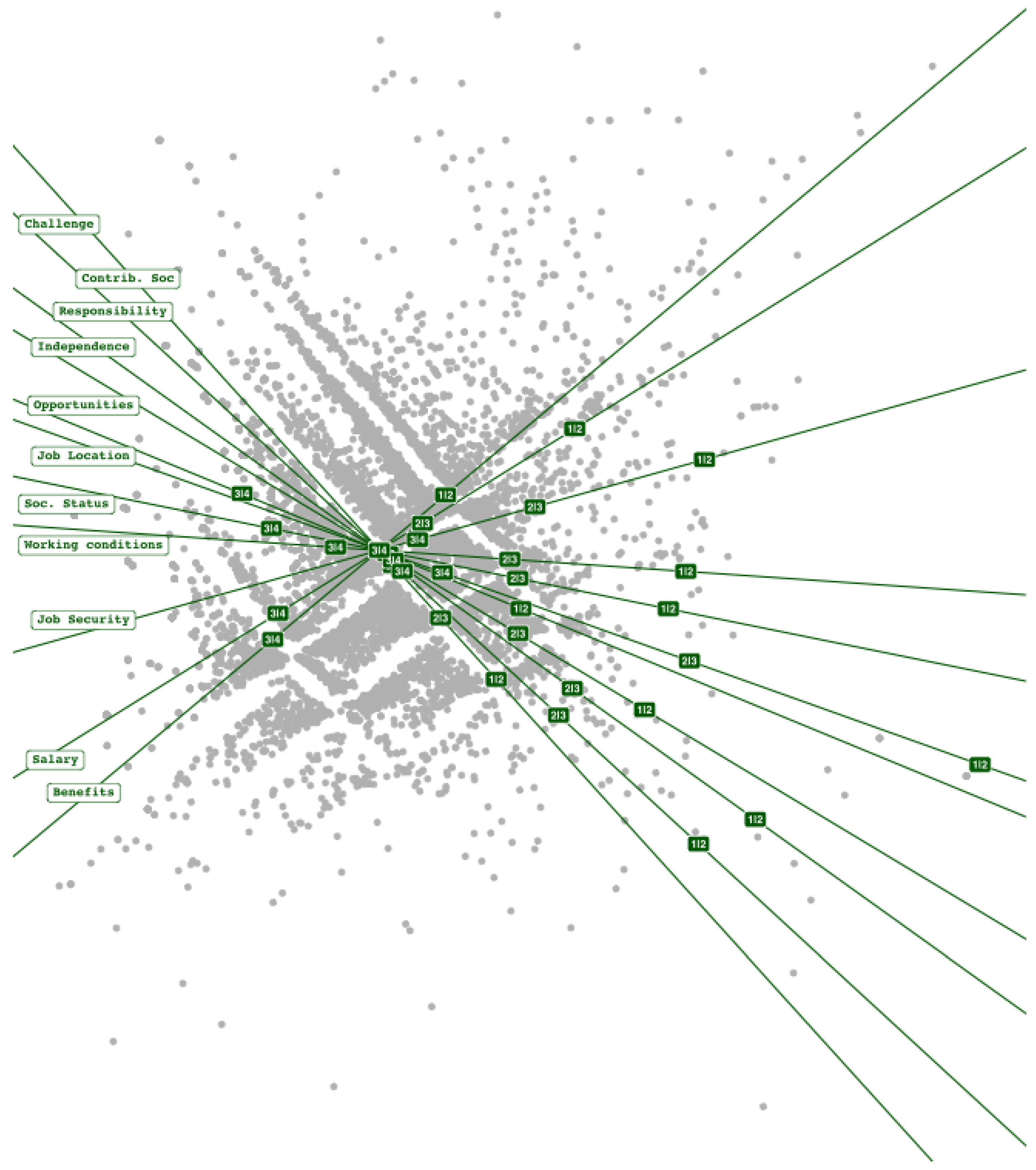

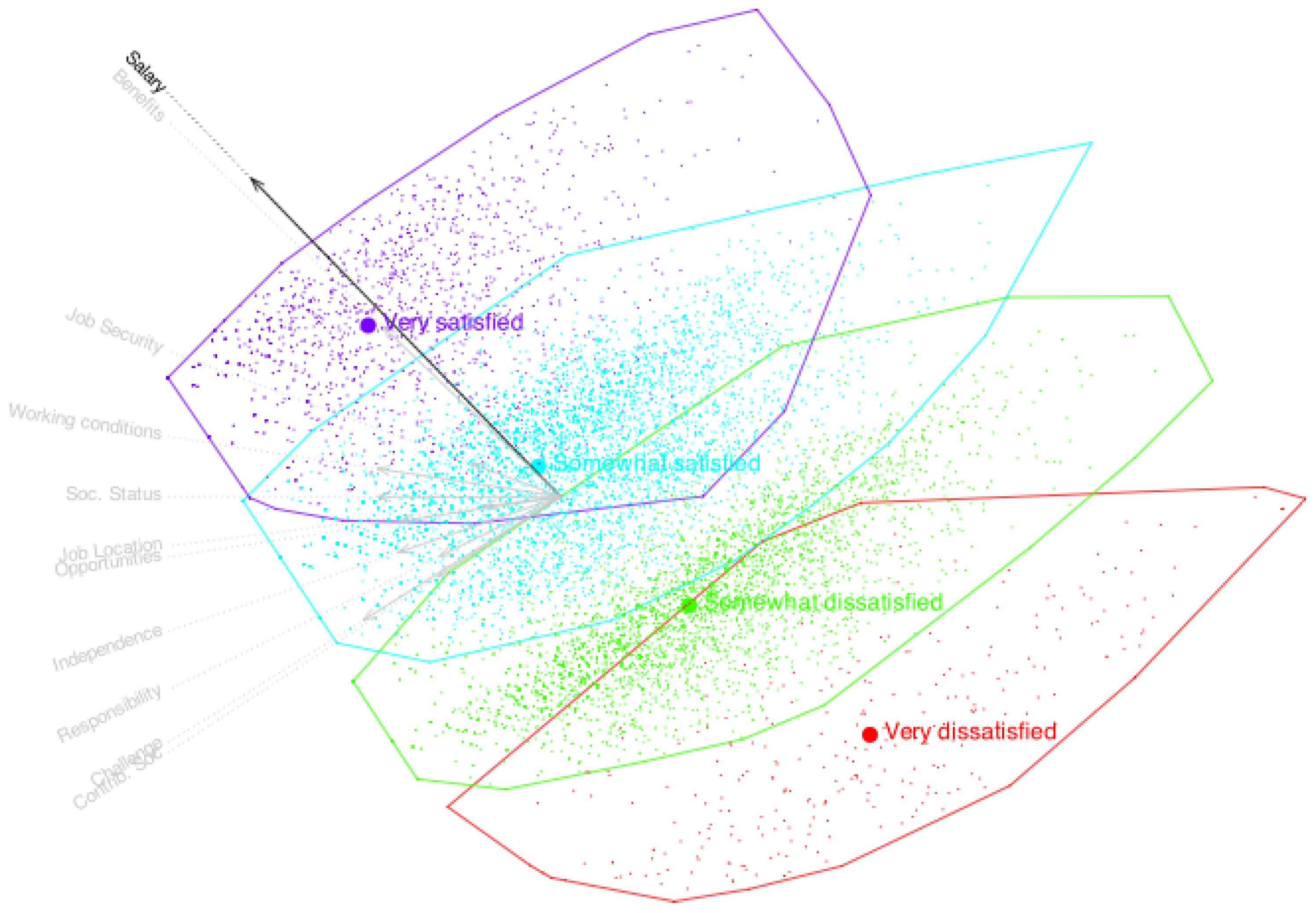

The biplot of the ordinal data is shown in

Figure 8, where points represent individuals and vectors indicate the directions associated with the variables. In addition to the numerical fit measures presented earlier, graphical representations such as biplots are valuable tools for interpreting patterns in the data. Biplots allow for the simultaneous visualization of key characteristics in both individuals and variables, as well as the relationships between them.

Although we did not initially consider our biplots within the traditional frameworks of JK (RMP) or GH (CMP) biplots, the relationship between the coordinates and factor loadings discussed in

Section 3.4 indicates that the proposed biplots correspond to the GH type, in which emphasis is placed on the variables. In this type of biplot, the angles between variable directions represent correlations—specifically, polychoric correlations among ordinal variables in our case. Small acute angles indicate strong positive correlations, angles approaching

suggest strong negative correlations, and right angles indicate a lack of correlation.

Some variables exhibit similar behavior—for instance, level of responsibility, intellectual challenge, and contribution to society—as reflected by the small angles between their corresponding directions. Although some groups of variables have very similar directions, the predicted category boundaries within these groups may still differ significantly. This is observed, for example, with opportunities for advancement and degree of independence.

Individual markers are represented by small dots and, to avoid visual clutter, are not labeled, as the analysis does not focus on any specific individual. In general, the distances between individual points reflect their similarity: the closer two points are, the more similar their response patterns tend to be. This graphical structure often reveals clusters of similar individuals and the variables responsible for those groupings. Clusters may also be identified using external nominal variables to assess whether the extracted dimensions are associated with known groupings.

The projection of an individual onto the direction of a variable allows for category prediction. Threshold points separating adjacent categories are marked along each variable’s direction using numeric labels. For example, a point marked “1” indicates the threshold for switching the prediction from the first to the second category, “2” indicates the threshold between the second and third categories, and so on.

The figure may be further improved by using different colors for each variable, as shown in

Figure 9. This visual aid enhances the readability of the plot and helps distinguish category thresholds for each variable.

All variables display three threshold marks, except for job security, which has only two (1 and 2), indicating that category 3 is never predicted. In other words, the probability of an individual falling into category 3 is never higher than that of other categories; thus, it is considered a hidden or never-predicted category.

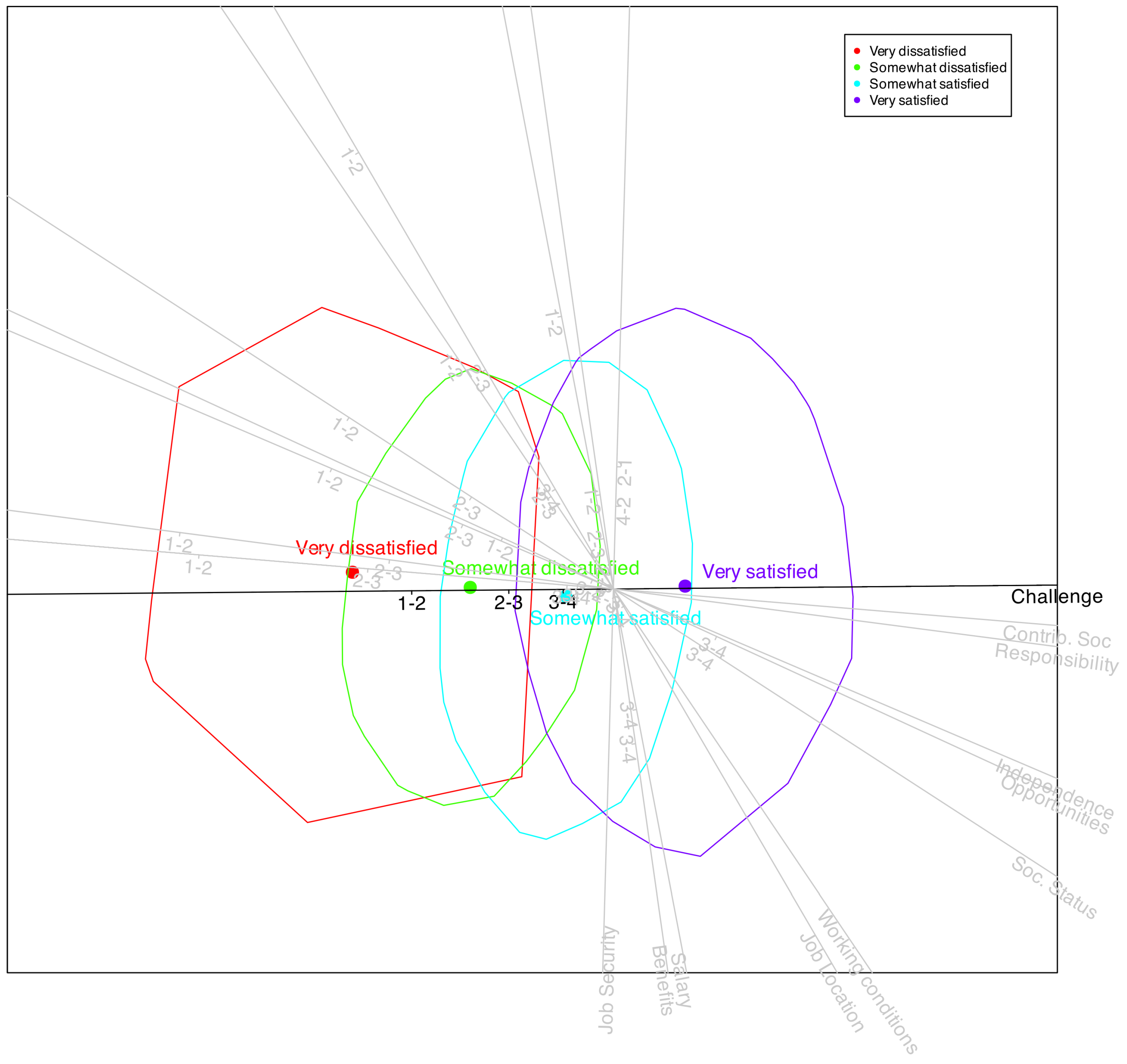

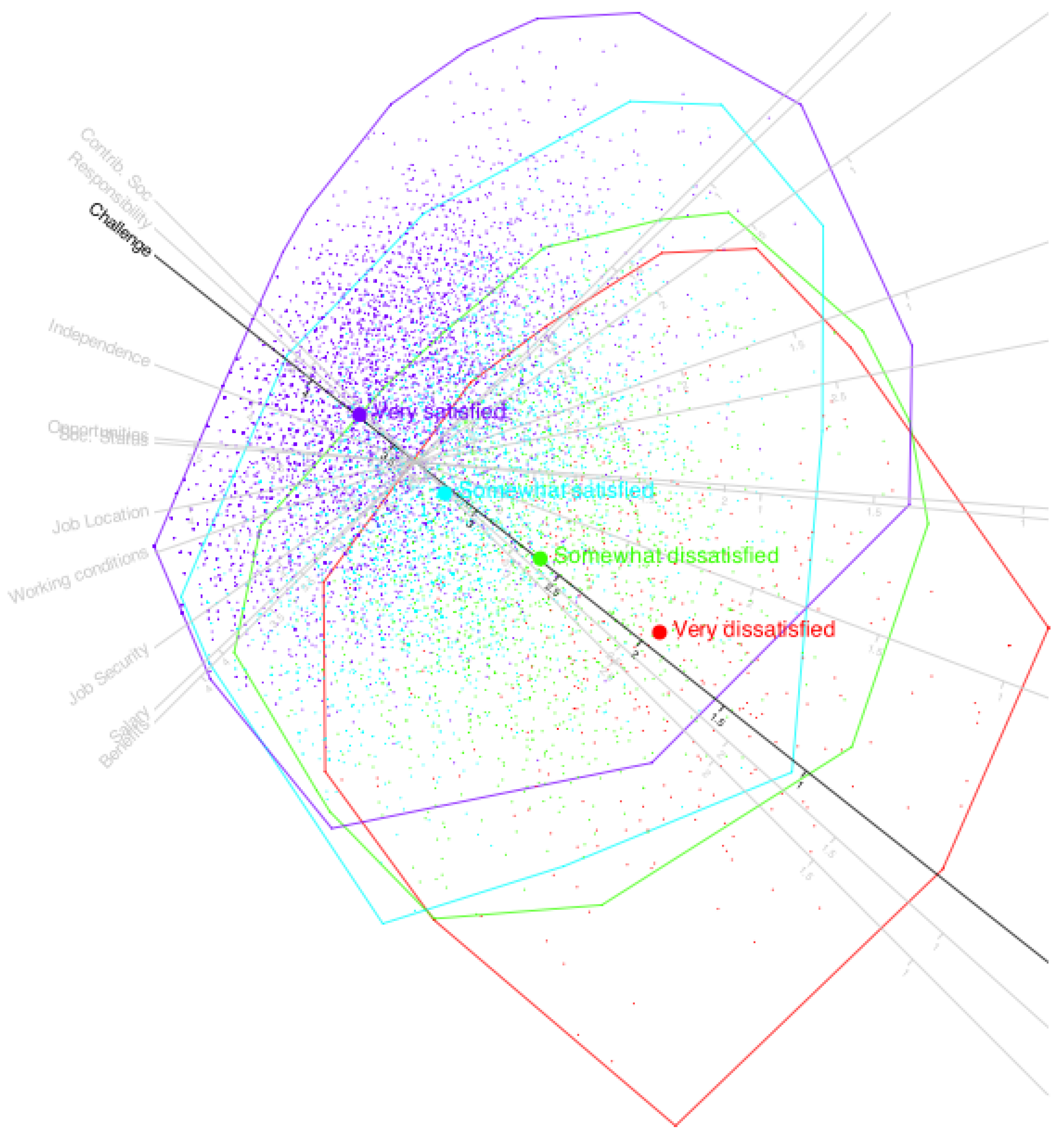

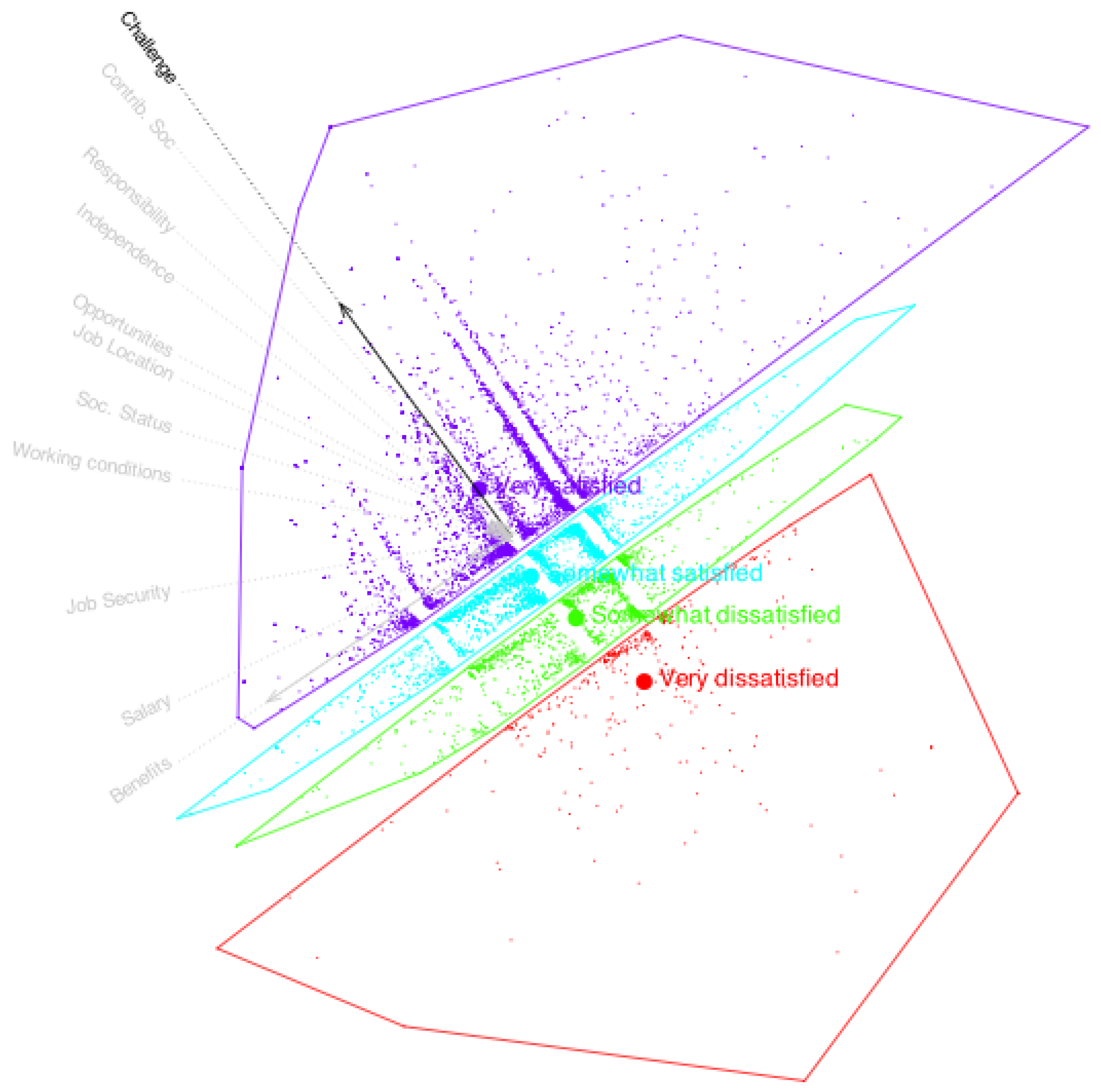

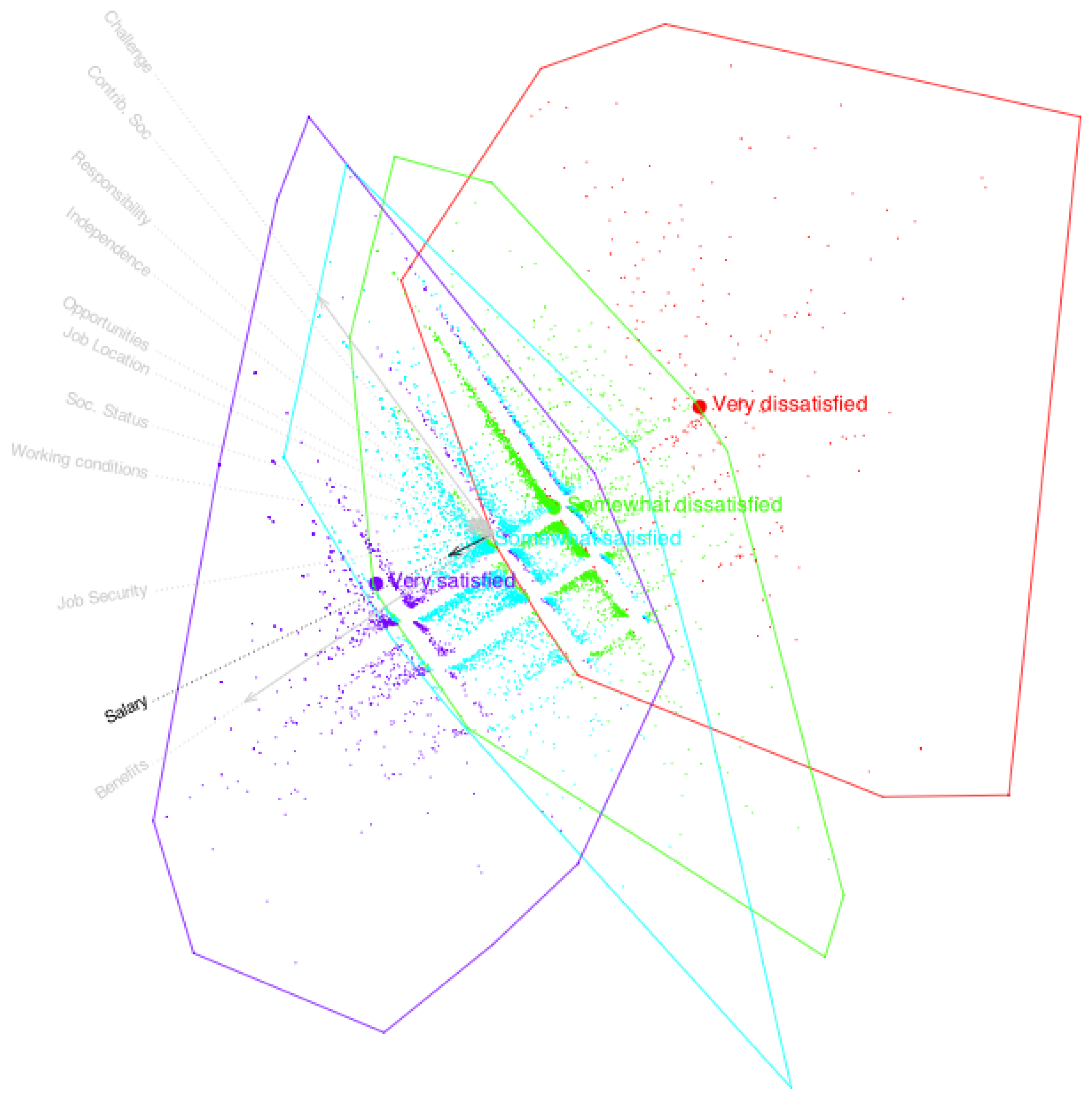

The biplot visually reflects the underlying factor structure of the dataset. To illustrate how the geometry captures the structure of a particular variable, we can enhance the plot by clustering individuals according to their observed response categories.

Figure 10 shows such a representation for the variable

Challenge, where individuals are colored or marked based on their observed categories. This visualization highlights how the model’s prediction boundaries align with actual response patterns.

We observe that the cluster centers are closely arranged along the direction of the variable Challenge, indicating that this axis effectively captures the underlying pattern of that variable. A similar analysis can be performed for the remaining variables, confirming that the biplot reflects the structure of all variables, albeit to different degrees. The fit indices previously discussed provide a quantitative measure of how well each variable is represented in the low-dimensional space.

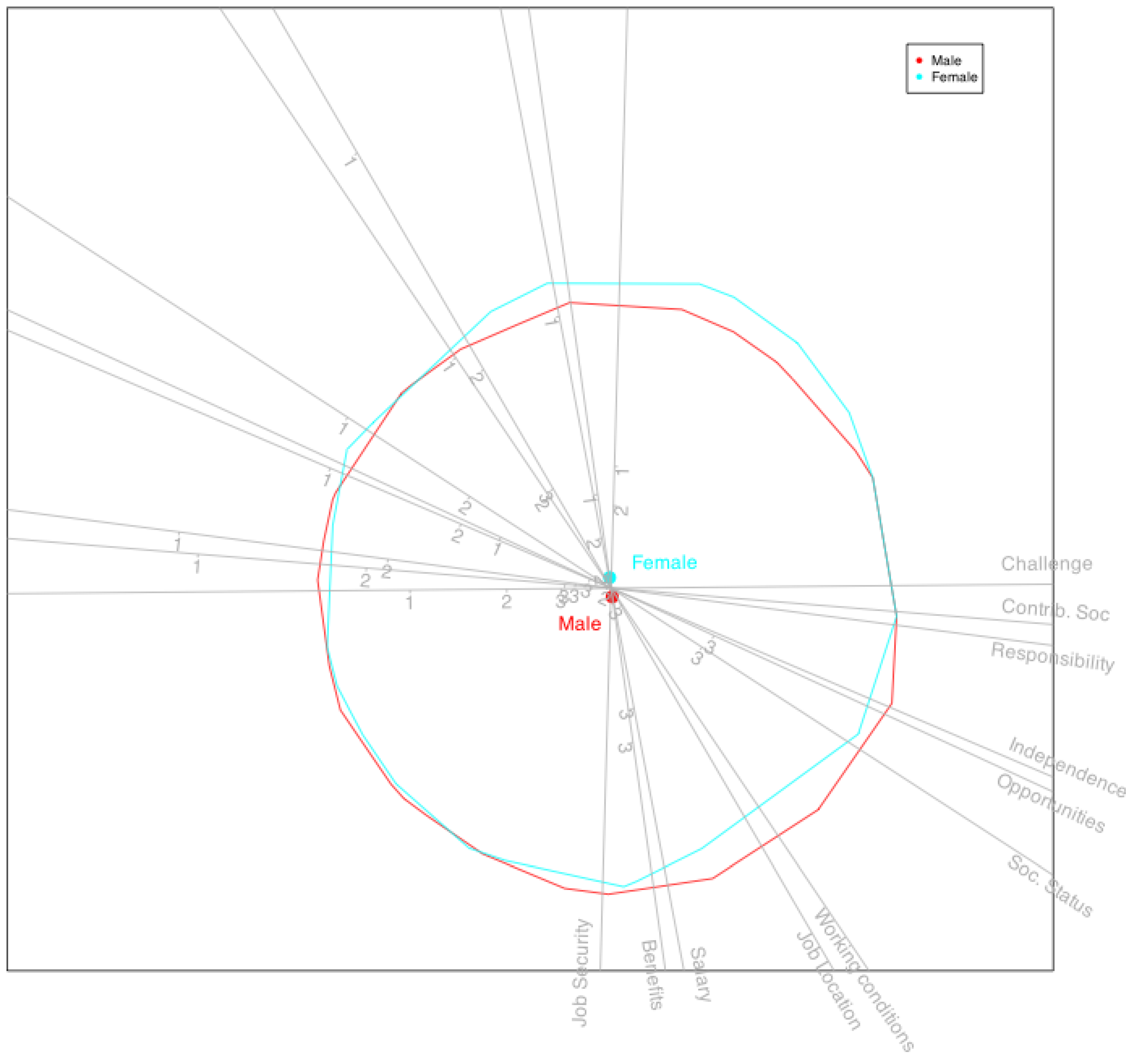

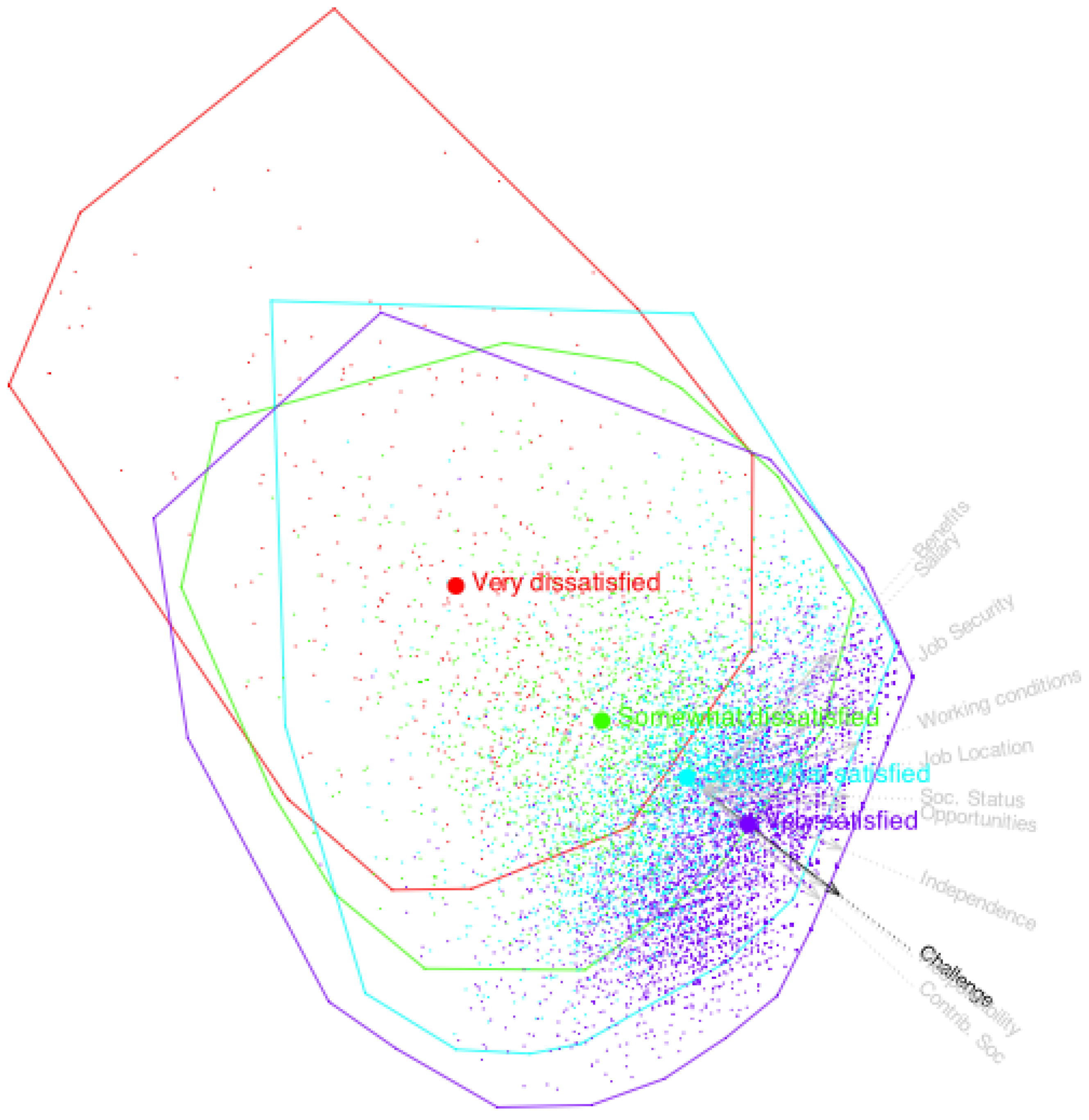

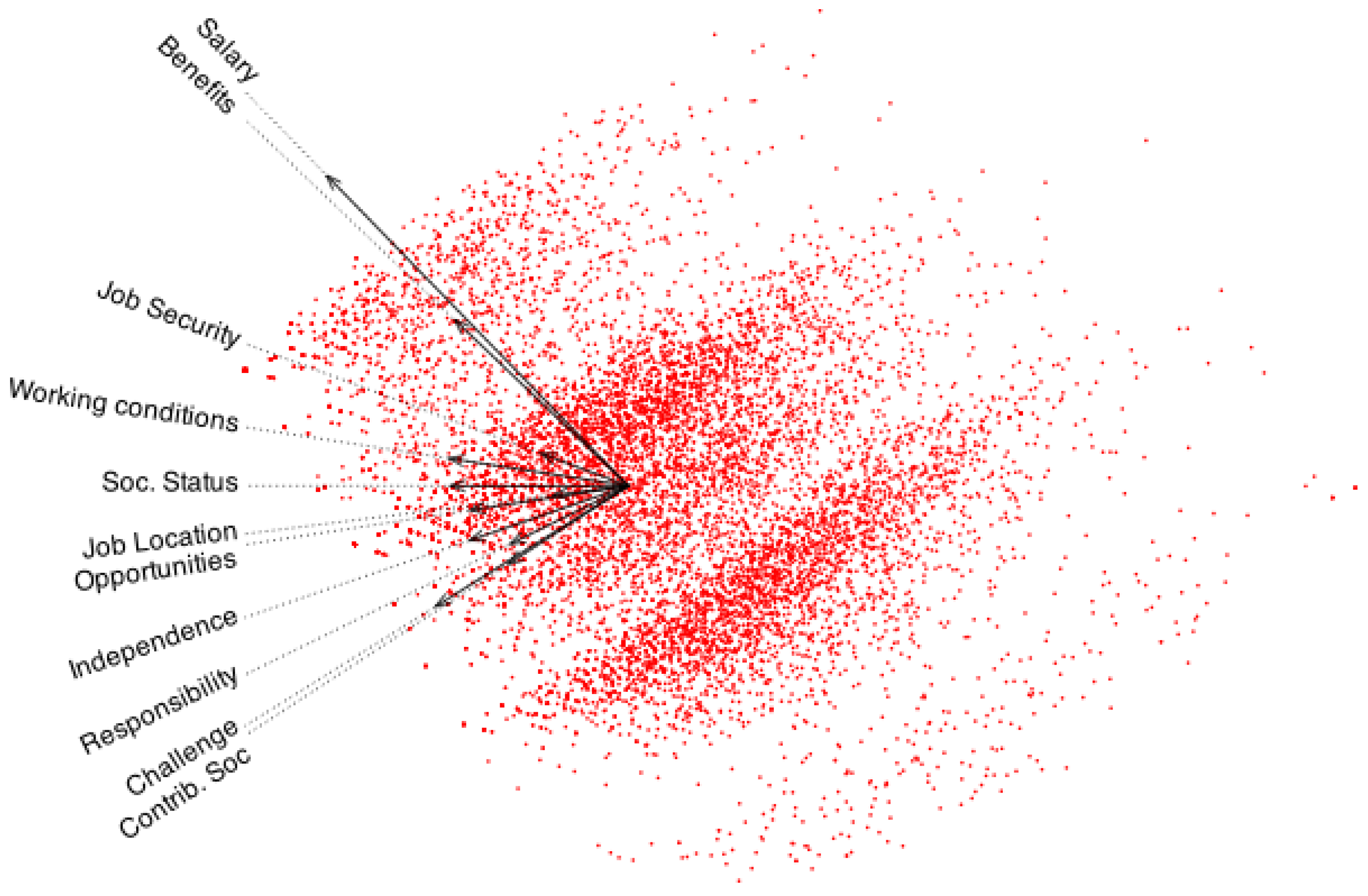

The final biplot can also be used to examine the behavior of different groups of individuals defined by external nominal variables—for example, comparing males and females to explore potential relationships between job satisfaction and gender.

Figure 11 presents such a comparison.

The positions of men and women, represented by the centroids of their coordinates on the biplot, are virtually indistinguishable (

Figure 11). This suggests that there are minimal differences between male and female doctorate holders in how they perceive job satisfaction.