Variational Autoencoders-Based Algorithm for Multi-Criteria Recommendation Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We propose a novel VAE-based model tailored for multi-criteria recommendation systems (VAE-MCRS), which incorporates both latent representation vectors and user–item interactions.

- We demonstrate that incorporating multiple item aspects (i.e., multi-criteria ratings) enables the proposed VAE-MCRS model to utilize its generative capabilities effectively within the multi-criteria recommendation framework. The proposed model is capable of capturing rather complex dependencies among the various criteria as well as the overall user preferences, thus enhancing recommendation accuracy.

- We conduct an extensive set of experiments on a real-world multi-criteria dataset (Yahoo! Movies), comparing the VAE-MCRS model with various stare-of-the-art recommendation models. The experimental results validate the effectiveness of the proposed model, highlighting its advantage over other baseline recommendation models in terms of recommendation accuracy.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Deep Learning Models in Recommender Systems

- Capturing non-linear relationships: deep learning models effectively allow for the extraction of non-linear relationships between users and items, which are often overlooked by traditional methods. This is crucial for understanding nuanced preferences and providing more accurate recommendations [12,13].

- Handling high-dimensional data: deep learning models remain capable of handling extremely high-dimensional data, emerging as a challenge in recommender systems. Such models have the capacity to extract low-dimensional representations, thereby simplifying the complexity of problems while still preserving all informative contents, with a data sample size large enough to make conventional statistical methods ineffective [12,13].

- Addressing data sparsity: deep learning models can effectively deal with the problem of sparsity of data, which can occur when information about user preferences or item attributes is limited. They can learn from incomplete data and hence make accurate predictions even when user interactions are limited [12,13].

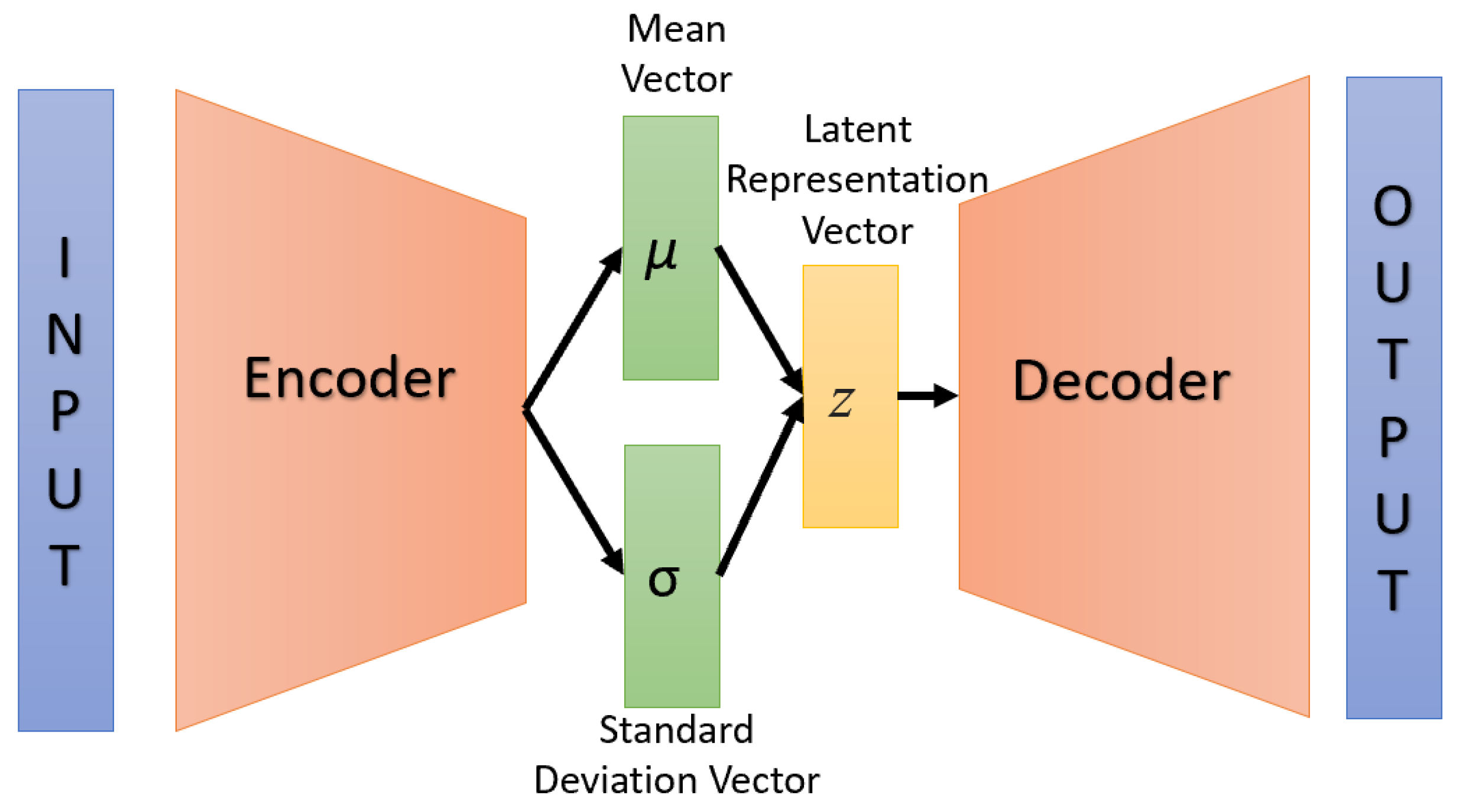

2.2. Variational Autoencoders

2.3. Variational Autoencoder-Based Recommender Systems

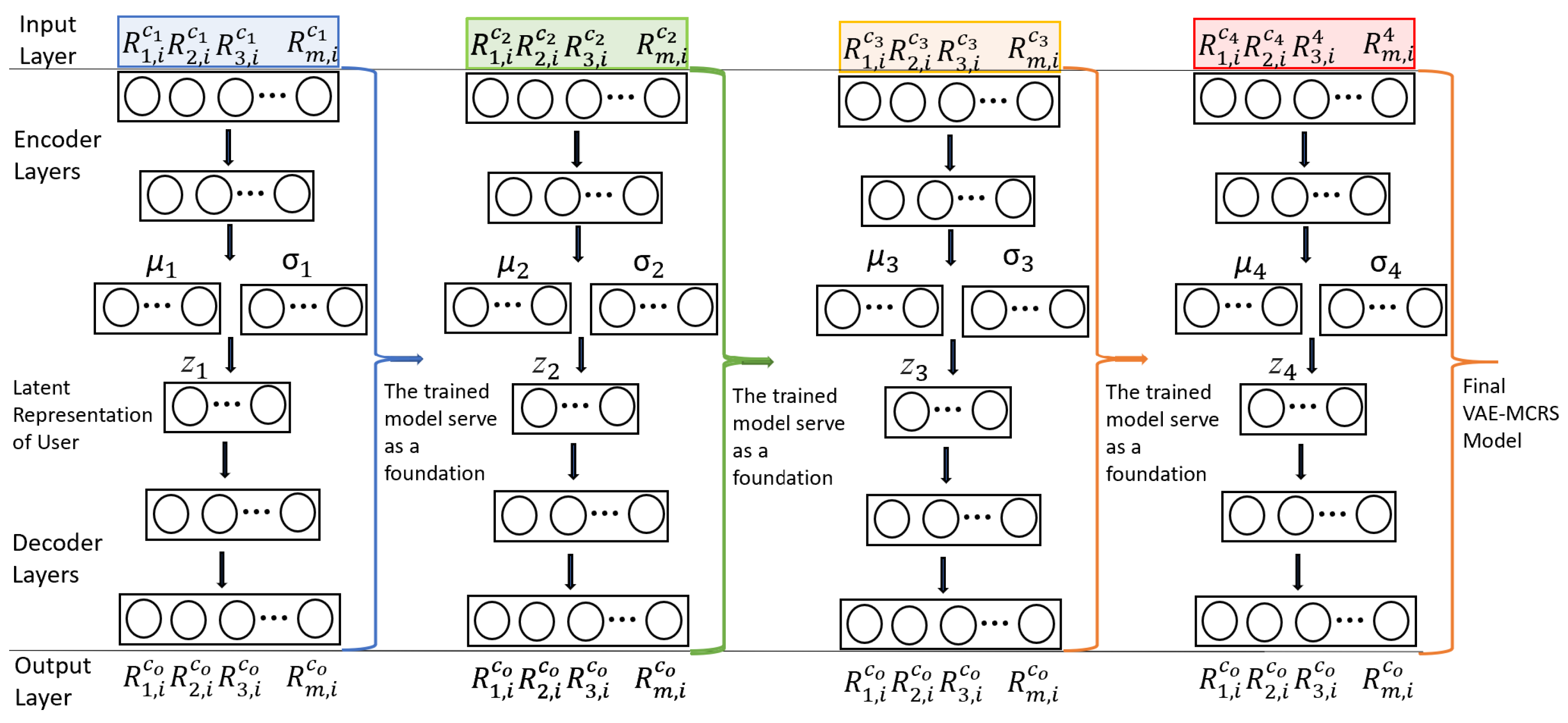

3. Proposed Variational Autoencoder Model

| Algorithm 1 Multi-criteria variational autoencoder for collaborative filtering-based recommender systems VAE-MCRS. |

Input: Multi-criteria dataset. Output: Recommendation prediction. First stage: Dataset and VAE-MCRS model preparation Step 1: Clean missing values, duplication, standardization (rating range [1–5]) ▹ Data preprocessing Step 2: For each criterion, construct a matrix where N rows represent N users and M columns represent M movies. ▹ Construct User–Movie Matrix Step 3: Split dataset on 80% for training and 20% for testing. Step 4: Initialize the hyper-parameters of the VAE-MCRS encoder and decoder networks. ▹ Initialization phase. Second stage: Train VAE-MCRS model Step 5: Maps the user’s ratings to two vectors: mean and standard deviation of the latent space (representing latent features). ▹ Encoding phase. Step 6 The encoder produces two vectors:

▹ Latent representation phase. Step 7: Construct the latent representation vector z using the mean and the standard deviation vectors. ▹ Reparameterization phase. Step 8: Decodes the latent vector z back into predicted ratings for all movies, including those that the user has not rated. ▹ Decoding phase. Step 9: For each new criterion, go back to Step 5 to train the trained VAE-MCRS model with the rating matrix of the new criteria. Step 10: Feed VAE-MCRS with testing data for prediction. |

- When trained sequentially on a multiple criteria ratings dataset (for example, Acting, Story, Direction, and Visuals), the VAE can learn a shared latent space that effectively captures users’ preferences across all the criteria. This process results in a compact latent representation of a user’s overall preferences, considering how preferences for one criterion (e.g., Acting) may relate to others (e.g., Direction). For example, the VAE might learn that users who rate Acting highly also tend to rate Direction highly, or that users with strong Visuals preferences might not care as much about the Story. This shared latent space enables the model to gain a deeper understanding of user behavior across all criteria, ultimately improving its predictive accuracy and recommendation effectiveness.

- In a multi-criteria recommendation system, user preferences are not always independent. There may be complex, nonlinear interactions between different criteria. For example, a user might only value strong Direction if the Story is equally compelling. Traditional linear models may struggle to capture these relationships. However, the VAE is designed to handle such nonlinear interactions through the learning of the compressed latent vector. The VAE can learn how different criteria influence each other and combine them into one preference profile that reflects the complex dynamics of user preferences.

- In a real case, users do not provide ratings for all criteria (for example, a user may rate Acting and Visuals, but omit Story and Direction). The VAE model, well regarded for handling missing data, addresses this challenge by inferring missing ratings based on the ratings provided. By learning the distribution of preferences across all users and criteria, the VAE can estimate likely values for unrated criteria. For instance, if a user rates highly on Acting and Direction but leaves Visuals unrated, the VAE can predict the likely Visuals rating based on patterns learned from similar users. This ability is crucial when training the model on multiple criteria datasets sequentially, as it ensures robust performance even when full information is not available for every user or criterion.

- The VAE applies Gaussian distribution to the latent space for regularization. This regularization helps prevent overfitting to specific criteria and encourages the model to generalize across the dataset. As a result, the VAE balances the influence of each criterion and achieves a balanced representation of user preferences across all criteria (i.e., no single criterion dominates).

- By training on all criteria datasets sequentially, the VAE can generate personalized recommendations that reflect users’ true preferences across different aspects. Rather than optimizing the model for each criterion independently (which may lead to partial or less coherent recommendations), the VAE enables the model to understand how user ratings for criteria such as Acting, Story, Direction, and Visuals are correlated. For example, if a user rates Visuals ‘very good’ but has moderate preferences for Acting, the VAE will use the learned latent representation to recommend movies that balance these preferences, like movies with strong visuals but average acting. It also enables the model to make a list of recommendations by understanding user preferences across different combinations of criteria.

- When VAE is trained on a multi-criteria dataset, it can suggest items based on different aspects. For example, if a user favors Story and Visuals, the VAE might recommend a movie that excels in these aspects or suggest a movie with strong Direction and Acting, providing diverse relevant options.

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

4.1. Evaluation Metrics

4.2. Dataset

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis

4.4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ko, H.; Lee, S.; Park, Y.; Choi, A. A survey of recommendation systems: Recommendation models, techniques, and application fields. Electronics 2022, 11, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, K.; Satapathy, R.; Wang, S.; Cambria, E. Recent developments in recommender systems: A survey. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 2024, 19, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shambour, Q.Y.; Hussein, A.H.; Kharma, Q.M.; Abualhaj, M.M. Effective Hybrid Content-Based Collaborative Filtering Approach for Requirements Engineering. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 2022, 40, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shambour, Q.Y.; Abu-Alhaj, M.M.; Al-Tahrawi, M.M. A Hybrid Collaborative Filtering Recommendation Algorithm for Requirements Elicitation. Int. J. Comput. Appl. Technol. 2020, 63, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, C.C. Neighborhood-based collaborative filtering. In Recommender Systems: The Textbook; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 29–70. [Google Scholar]

- Adomavicius, G.; Kwon, Y. New recommendation techniques for multicriteria rating systems. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2007, 22, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, D.; Rizzo, G.; Morisio, M. A systematic literature review of multicriteria recommender systems. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2021, 54, 427–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomavicius, G.; Manouselis, N.; Kwon, Y. Multi-criteria recommender systems. In Recommender Systems Handbook; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 769–803. [Google Scholar]

- Nilashi, M.; Dalvi-Esfahani, M.; Roudbaraki, M.Z.; Ramayah, T.; Ibrahim, O. A Multi-Criteria Collaborative Filtering Recommender System Using Clustering and Regression Techniques. J. Soft Comput. Decis. Support Syst. 2016, 3, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Nilashi, M.; Ibrahim, O.B.; Ithnin, N. Hybrid recommendation approaches for multi-criteria collaborative filtering. Expert Syst. Appl. 2014, 41, 3879–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, S.; Basak, S.; Saikia, P.; Paul, S.; Tsalavoutis, V.; Atiah, F.; Ravi, V.; Peters, A. A review of deep learning with special emphasis on architectures, applications and recent trends. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 194, 105596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayemowa, M.O.; Ibrahim, R.; Bena, Y.A. A systematic review of the literature on deep learning approaches for cross-domain recommender systems. Decis. Anal. J. 2024, 13, 100518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debbah, A.; Lagrini, S. Latest advances in deep learning-based recommender systems. Int. J. Reason.-Based Intell. Syst. 2024, 16, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yao, L.; Sun, A.; Tay, Y. Deep learning based recommender system: A survey and new perspectives. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2019, 52, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, B.; Szlichta, J.; Salehi-Abari, A. Variational autoencoders for top-k recommendation with implicit feedback. In Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Virtual Event, Canada, 11–15 July 2021; pp. 2061–2065. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Hou, L.; Liang, S.; Zhu, H.; Yu, J.; Liu, Y.; Yin, J. Revisiting Positive and Negative Samples in Variational Autoencoders for Top-N Recommendation. In International Conference on Database Systems for Advanced Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 563–573. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Uu, R.L.H.; Liang, S.; Zhu, H.; Yu, J.; Liu, Y.; Yin, J. VAE*: A Novel Variational Autoencoder via Revisiting Positive and Negative Samples for Top-N Recommendation. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 2024, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, I.S.; Tewari, A.S.; Tiwari, A.K. An autoencoder-based deep learning model for solving the sparsity issues of Multi-Criteria Recommender System. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 235, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenbin, I.; Alekseev, A.; Tutubalina, E.; Malykh, V.; Nikolenko, S.I. Recvae: A new variational autoencoder for top-n recommendations with implicit feedback. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Houston, TX, USA, 3–7 February 2020; pp. 528–536. [Google Scholar]

- Spoorthy, G.; Sanjeevi, S.G. Multi-criteria recommendations using autoencoder and deep neural networks with weight optimization using firefly algorithm. Int. J. Eng. 2023, 36, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shambour, Q. A deep learning based algorithm for multi-criteria recommender systems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 211, 106545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batmaz, Z.; Kaleli, C. AE-MCCF: An autoencoder-based multi-criteria recommendation algorithm. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2019, 44, 9235–9247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Krishnan, R.G.; Hoffman, M.D.; Jebara, T. Variational autoencoders for collaborative filtering. In Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference, Lyon, France, 23–27 April 2018; pp. 689–698. [Google Scholar]

- Fraihat, S.; Tahon, B.A.; Alhijawi, B.; Awajan, A. Deep encoder–decoder-based shared learning for multi-criteria recommendation systems. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 24347–24356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yücebacs, S.C. MovieANN: A Hybrid Approach to Movie Recommender Systems Using Multi Layer Artificial Neural Networks. Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü Dergisi 2019, 5, 214–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shardanand, U.; Maes, P. Social information filtering: Algorithms for automating “word of mouth”. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, FL, USA, 7–11 May 1995; pp. 210–217. [Google Scholar]

- Alodhaibi, K. Decision-Guided Recommenders with Composite Alternatives. Ph.D. Thesis, George Mason University, Fairfax County, VA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Hyperparameters | Experiments Using |

|---|---|

| Optimizer | Adagrad, SGD, Adam, RMSprop |

| Activation Functions | Softmax, ELU, RELU, Sigmoid |

| Hidden Layers | 7, 5, 3 |

| Hyperparameters | VAE-MCRS |

|---|---|

| Output Layer Activation Function | Sigmoid |

| Hidden Layers Activation Function | ELU |

| Number of Hidden Layers | 3 |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| dropout | 0.5 |

| Learning Rate | 0.01 |

| Epochs with Early Stopping | 100 |

| Batch Size | 32 |

| Hidden Layers | VAE-MCRS | |

|---|---|---|

| MAE | RMSE | |

| 3 Layers | 0.6038 | 0.7085 |

| 5 Layers | 0.6691 | 0.8099 |

| 7 Layers | 0.7016 | 0.8849 |

| Activation Function | VAE-MCRS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hidden Layers | Output Layer | MAE | RMSE |

| ELU | ELU | 0.7231 | 1.054 |

| ELU | Softmax | 0.6709 | 0.7903 |

| ELU | Sigmoid | 0.6038 | 0.7085 |

| RELU | Sigmoid | 0.6102 | 0.7125 |

| Optimizer | VAE-MCRS | |

|---|---|---|

| MAE | RMSE | |

| Adagrad | 0.9236 | 1.2086 |

| Adam | 0.6038 | 0.7085 |

| RMSprop | 0.6795 | 0.8604 |

| SGD | 1.3558 | 1.7642 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fraihat, S.; Shambour, Q.; Al-Betar, M.A.; Makhadmeh, S.N. Variational Autoencoders-Based Algorithm for Multi-Criteria Recommendation Systems. Algorithms 2024, 17, 561. https://doi.org/10.3390/a17120561

Fraihat S, Shambour Q, Al-Betar MA, Makhadmeh SN. Variational Autoencoders-Based Algorithm for Multi-Criteria Recommendation Systems. Algorithms. 2024; 17(12):561. https://doi.org/10.3390/a17120561

Chicago/Turabian StyleFraihat, Salam, Qusai Shambour, Mohammed Azmi Al-Betar, and Sharif Naser Makhadmeh. 2024. "Variational Autoencoders-Based Algorithm for Multi-Criteria Recommendation Systems" Algorithms 17, no. 12: 561. https://doi.org/10.3390/a17120561

APA StyleFraihat, S., Shambour, Q., Al-Betar, M. A., & Makhadmeh, S. N. (2024). Variational Autoencoders-Based Algorithm for Multi-Criteria Recommendation Systems. Algorithms, 17(12), 561. https://doi.org/10.3390/a17120561