1. Introduction

One of the most important legacies in numerical analysis in the 20th century is the resolution of nonlinear equations by using high-order iterative methods, since we often encounter nonlinear mathematical models for which there are no analytical methods that allow us to find a solution of the nonlinear equation

. This topic has attracted researchers from different areas, such as Traub in [

1], who initiated the analysis of these methods.

Recently, Petković et al. (in [

2]) and Amat et al. (in [

3]) collected and updated the state of the art of multipoint methods. The advantage of this type of method is that it does not use higher-order derivatives, and it is of great practical importance because it overcomes the theoretical limitations of one-point methods. The latter are not good alternatives for increasing the order of convergence and the computational efficiency rate.

When the order of an iterative method increases, so does the number of functional evaluations per step. Ostrowski’s efficiency index (see [

4]) gives a measure of the balance between these quantities, according to the formula

, where

p is the order of convergence of the method and

d is the number of functional evaluations per iteration. According to the Kung–Traub conjecture [

5], the order of convergence of any multipoint method without memory cannot exceed the limit

, which is called the optimal order. Therefore, the optimal order of a method with three functional evaluations per step is 4. King’s family of methods [

6], of which Ostrowski’s method [

4] is a particular case, as is Jarratt’s method [

7] and some of the families of multistep methods studied extensively in Traub’s book [

8], are optimal fourth-order methods, since they perform only three functional evaluations per step. In recent years, as the extensive literature shows, there has been a renewed interest in the search for multistep methods in order to achieve optimal order convergence and, thus, better efficiency.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 is devoted to the presentation of a family of iterative methods that will be subjected to a dynamical analysis in

Section 3. The stability of fixed points is studied, and the stable and unstable elements of the family are selected by means of the generation of the parameter plane. Some numerical tests are performed in

Section 4, showing the performance of selected stable and unstable methods in comparison with other known ones. Finally, some conclusions are shown in

Section 5.

3. The Scaling Theorem

If the conjugation classes and the scaling theorem are verified for the method under study, it is possible to generalize a dynamical study on the polynomial of the second degree on which this study is performed. In this case, by applying this to a generic polynomial, such as

, we can assume that the result obtained will be equivalent to the result that we will obtain with any quadratic polynomial, since there will always be an affine transformation that takes us from this generic polynomial to any quadratic polynomial (see, for example, [

11]). We emphasize that this result is only fulfilled in methods that contain derivatives, which is the justification of this study.

Let

be the Riemann sphere. Let

be the fixed-point operator of iterative scheme (

11) on a function

f, that is,

where

In order to generalize the dynamical analysis of family (

11), we prove the following result.

Theorem 2 (Scaling Theorem)

. Let , be an affine mapping. In addition, let be a holomorphic function and with ; then, the fixed-point operator is an affine conjugate to by A, i.e., Proof. We will prove the following identity:

By developing the left side,

Furthermore, we know that the fixed-point operator related to function

h, for

, is:

Considering that

,

From the results obtained in (

14) and (

15),

Therefore, the method in (

11) satisfies the scaling theorem. □

Now, we analyze the dynamical behavior of this class in terms of parameter in order to determine the methods with good stability properties and avoid the members of the family whose behavior is unstable.

4. Dynamical Analysis

In this part, we use several tools of complex dynamics. Thus, we need the function f to be defined on the Riemann sphere .

In the following, we recall some concepts of complex dynamics. Let us suppose a fixed-point function on an arbitrary polynomial ; this gives a rational function, .

Indeed, if given a rational function

, where

represents the Riemann sphere, the orbit at a point

can be defined as

It is necessary to study the phase plane of by classifying the fixed points according to the asymptotic behavior related to their orbits. A is said to be a fixed point if . A periodic point , of period , is a point where and , where . A preperiodic point is a point that is not periodic, but there exists a such that is periodic. A point is a critical point of the rational function if . If a critical point is different from any of those related to the roots of polynomial , it is called a free critical point. In a similar way, the fixed points that are different from the roots of are called strange fixed points.

Moreover, a fixed point

is called an attractor if

, a superattractor if

, repulsive if

, and parabolic if

. Fixed points other than those associated with the roots of the polynomial

are called strange fixed points. The basin of attraction of an attractor

is defined as:

For the rational function

, the Fatou set of

, which is denoted by

, is the set of points

whose orbits tend to one attractor (a fixed point or periodic orbit). Its complement in

is the Julia set,

. That is, the basin of attraction from every fixed or periodic point belongs to the Fatou set, while the boundaries of these basins of attraction are in the Julia set (for more explanation, see [

12,

13,

14]).

The following result justifies the interest in the parameter planes that we will introduce later. The connected component of the basin of attraction, which contains the point or periodic orbit of attraction, is called the immediate basin of attraction.

Theorem 3 (Fatou–Julia). Let be a rational function. An immediate basin of attraction of any attractor has at least one critical point.

To any rational operator that satisfies the scaling theorem, we can apply a Möbius transformation, which is stated as follows. If

, then

depends on parameters

a and

b. To eliminate this dependency, we apply a Möbius transformation

h as follows:

where

which satisfies

,

.

Operators and have the same qualitative properties of stability.

With Theorem 2, we may find all of the stable behaviors of a rational function by analyzing its performance on the set of critical points, as we see below.

Using polynomial

, the iterative scheme (

11) on this polynomial provides the following rational operator:

where

. By applying the Möbius transformation on

, we obtain the rational operator to work, which is an operator free of parameters

a and

b.

and its inverse function is

To get the fixed-point operator,

So, becomes a conjugate using the Möbius transformation for in order to simplify the dynamical analysis. Note that the rational operator is not reliant upon the roots of , a, and b.

4.1. Stability of the Fixed Points

In this section, we analyze the stability of fixed points. We give some important results on the stability of strange fixed points, and we analyze the behavior of the rational operator on free critical points. The strange fixed points are

, and the roots of the polynomial are

which is denoted by

,

.

The stability of the strange fixed points is analyzed in the following result.

Theorem 4. The fixed points and , which are associated with the roots a and b, are superattractors regardless of the value of β. is a strange fixed point when , and its stability is determined as follows:

- (a)

If , then the fixed point is an attractor,

- (b)

If , then the fixed point is repulsive,

- (c)

If , then the fixed point is neutral.

Proof. By evaluating the rational operator , as well as its derivative at , we conclude that is a superattractor fixed point. For the punto , we derive the inverse of the operator , i.e., , and we evaluate it in . We can affirm that is a superattractor fixed point.

Now, we evaluate on the fixed point in order to determine its stability.

- (a)

, which implies that , and therefore if and only if and

- (b)

, which implies that , and, therefore, if and only if and .

- (c)

Finally, , which implies that , and, therefore, if and only if and .

This completes the proof. □

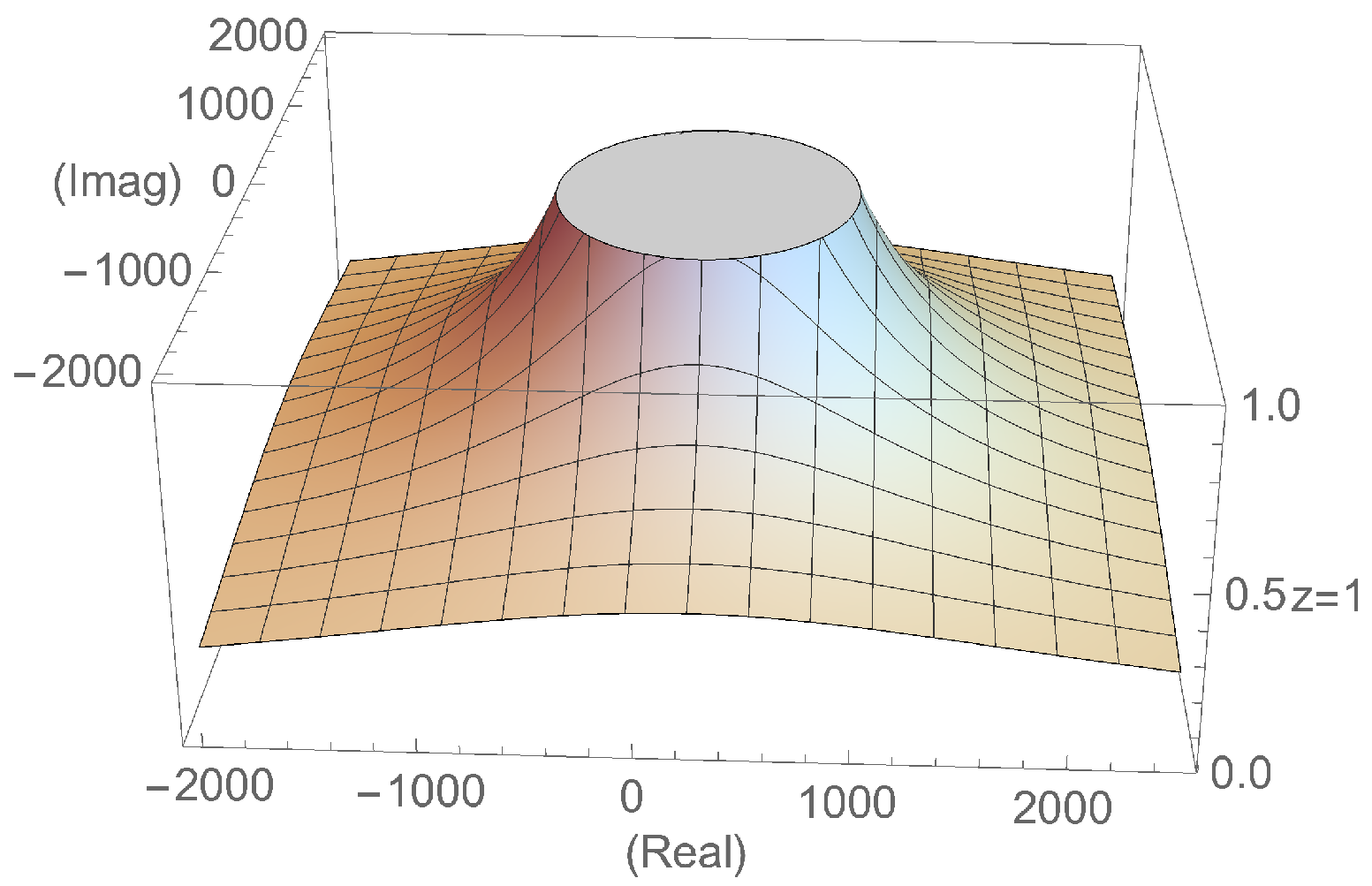

In

Figure 1, the stability of the strange fixed point

is presented.

Theorem 4 shows that we have two fixed points that are superattractors,

and

, and the strange fixed point

, for which we find different regions where this behaves as an attractor, repulsor, and parabolic for

. However, when we solve the equation

, six other solutions appear; these are strange fixed points that are solutions of the polynomial

(

18), which is denoted by

,

. In the following result, we analyze the stability of these strange fixed points.

Theorem 5. The strange fixed points of the rational operator , , , are all repulsors in a complex plane.

On the other hand, the strange fixed points are:

- 1.

attractors in the open interval . In particular, they are superattractors for .

- 2.

parabolics for .

- 3.

repulsors in the rest of the complex plane.

Finally, the strange fixed points are:

- 1.

attractors in and . In particular, they are superattractors for .

- 2.

parabolic at all points on the boundary of the circumference of the cone—in particular, for the complex numbers .

- 3.

repulsors in the rest of the complex plane.

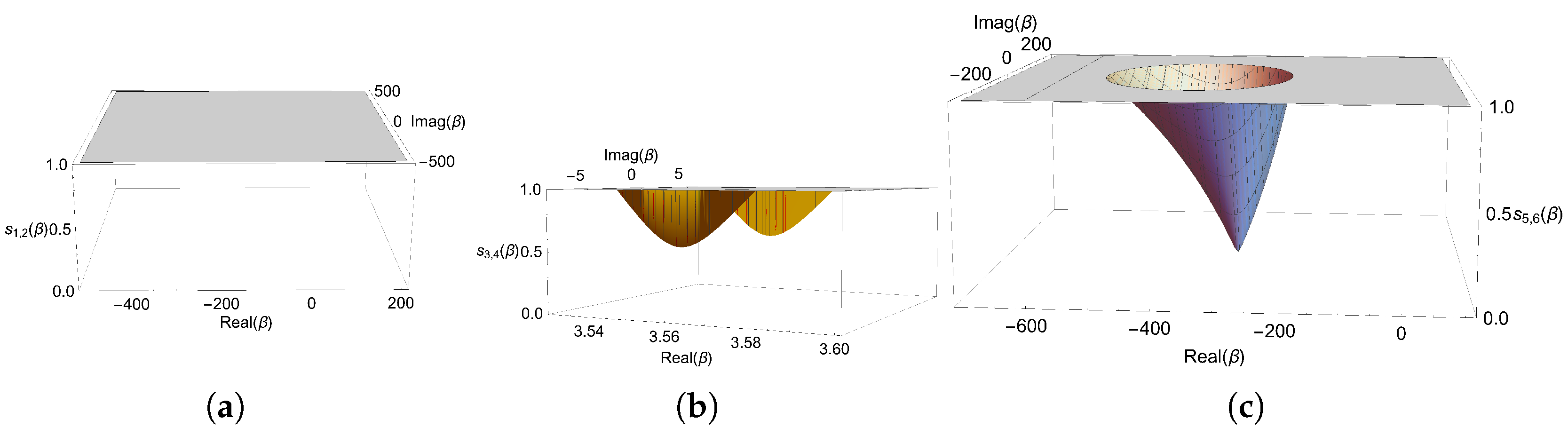

Theorem 5 cannot be analytically proven, since the substitution of these strange fixed points into the stability function results in roots of higher-order polynomials. Still, the stability regions in the complex plane of the strange fixed points

and

can be visualized in

Figure 2a, the stability regions of the fixed points

and

can be visualized in the complex plane in

Figure 2b, and the stability regions of the fixed points

and

can be visualized in the complex plane in

Figure 2c. Note that in the foreground, no stability region is visualized, which justifies the behavior of such strange fixed points; they are repulsors in the whole complex plane, and the strange fixed points

and

are attractors in the small region described in Theorem 5, while the strange fixed points

and

, are parabolic in the boundary of the circumference of the cone and are attracting inside the cone, being superattracting at the vertex of the cone. They are repulsive in the rest of the complex plane.

4.2. Critical Points

The critical points are obtained by solving equation . We obtain the points , , which correspond to the roots of polynomial , and the free critical points described in the following results.

Theorem 6. The free critical points of operator are:

- 1.

- 2.

Let us also remark that the critical points satisfy . So, they are not independent, and they have the same parameter plane.

There are also values of parameter for which the critical points coincide:

- (a)

The critical points match for .

- (b)

The points match if .

The free critical point is a pre-image of the strange fixed point because ; therefore, there is no need to obtain its related parameter plane because the information that would be obtained is contained in the stability function of .

6. Numerical Results

We use the functions proposed in

Table 1 to perform some numerical tests in order to analyze the results obtained with different known methods in comparison with the one proposed in the iterative family (

11).

We call the methods used for the numerical tests M1, M2, and M3. M3 is the method that we worked with in this manuscript, and M1 and M2 are two known fourth-order methods that we use to compare the numerical results; these are the scheme of C. Chun and the BCMT family, which can be found in [

16,

17].

where

where

.

where

.

The following expression can be used to estimate the theoretical order of convergence:

as presented by S. Weerakoon and T.G.I. Fernando in [

18]. However, the principal inconvenience of this

is that it requires knowledge of the precise root

. In order to solve such a problem, in [

19], Cordero and Torregrosa overhauled the definition of

so that it would not need the root to be exactly known at all, as shown in the following:

Calculations were performed by using the Matlab programming software with variable-precision arithmetic, with 200 digits of mantissa and as the error tolerance. For the computer programs, the following stopping criteria were used:

- (i)

or

- (ii)

.

Table 2 displays the best outcomes for each experiment. We can see how the following method is highly efficient compared to schemes such as Chun’s and the BCMT, which we used for comparison.

7. Conclusions

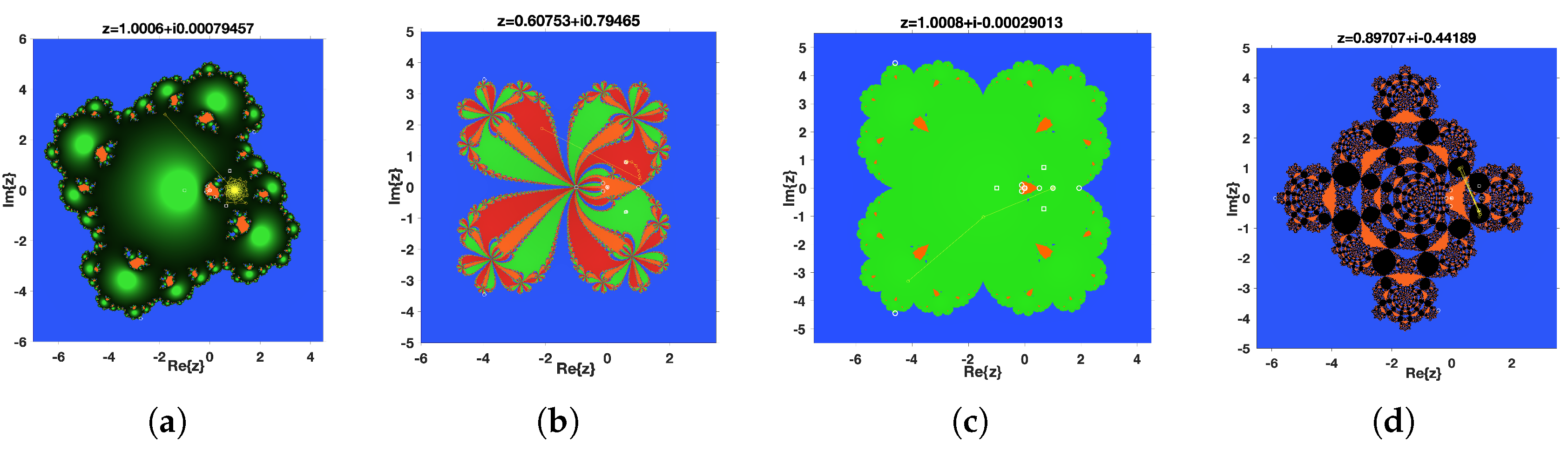

In our manuscript, we found a large, optimal, and general kind of fourth-order scheme that is free of second derivatives. The dynamical analysis that was performed on the proposed class of methods allowed us to choose family members that were particularly stable, discarding the ones with unstable performance, where strange fixed points and some periodical orbits were present. Lastly, we refer to

Table 2 to show that the suggested family is equal to or more competitive than the classical method, the recognized and efficient methods of Ostrowski and Maheshwari, and other recognized and efficient methods found in the literature. The dynamic study shows us that there are values of the parameter

for which we can obtain highly efficient iterative families of methods; some of the values that we can use are

,

,

, and

.

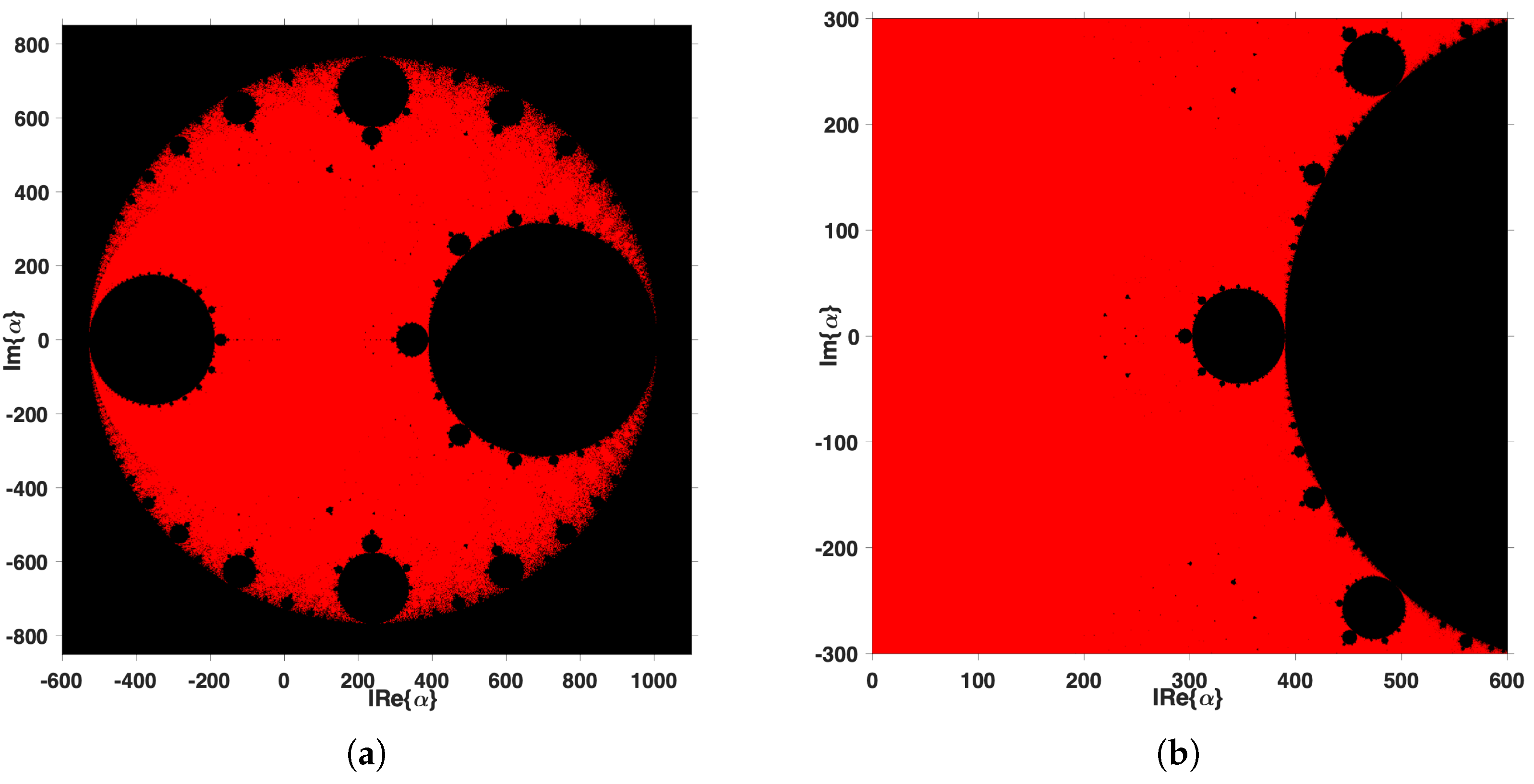

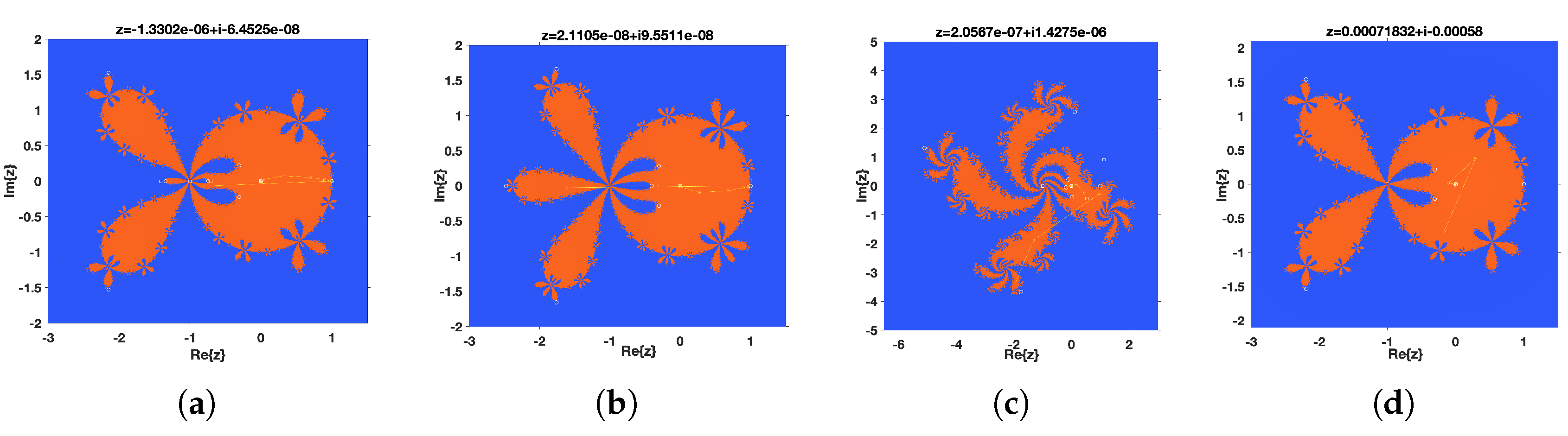

This behavior is justified in the dynamic planes given in

Figure 5a–d, since there is global convergence to the roots of a second-degree polynomial.

In addition, if we use parameter values corresponding to regions of instability, one of the consequences of using these schemes is that these do not converge to the root, and if they do converge, they would do so with a large number of iterations, that is, these members are unreliable. This fact can be confirmed in

Figure 4a–d.

The results shown in

Table 2 and

Table 3 are satisfactory from the point of view of numerical calculations. It can be observed that the number of iterations, computational time, and theoretical convergence order reached by our family, in comparison with the known methods of Chun and the BCMT, are satisfactory, as we expected, since we took one of the values of the

parameter for which it was theoretically shown that we would have efficient iterative methods. In addition, another piece of evidence that shows the degree of accuracy with which our method converges to the root is the computation of the absolute errors

and

, which are shown in

Table 3.