Facile Synthesis of CeO2-LaFeO3 Perovskite Composite and Its Application for 4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-Pyridyl)-1-Butanone (NNK) Degradation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

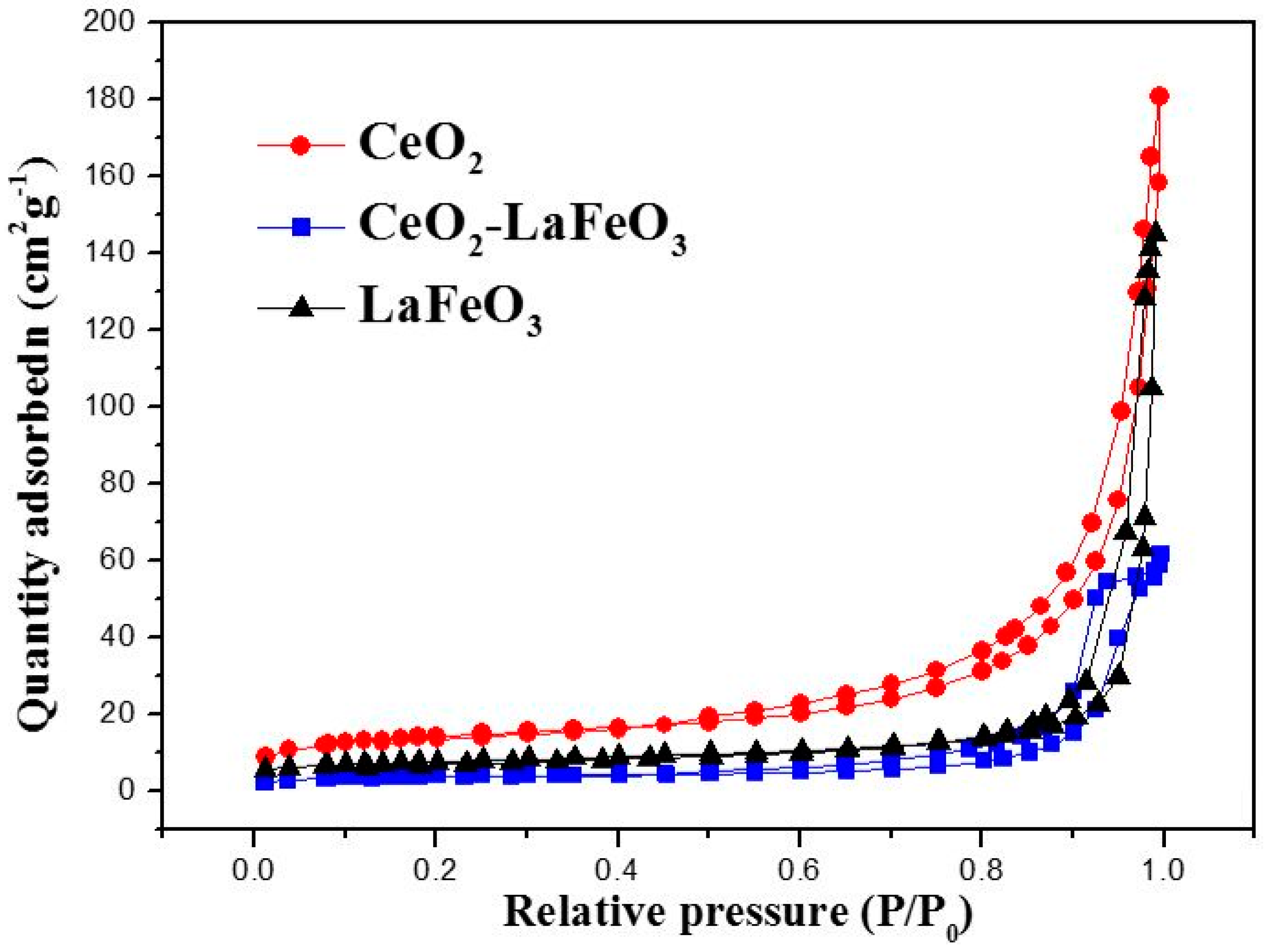

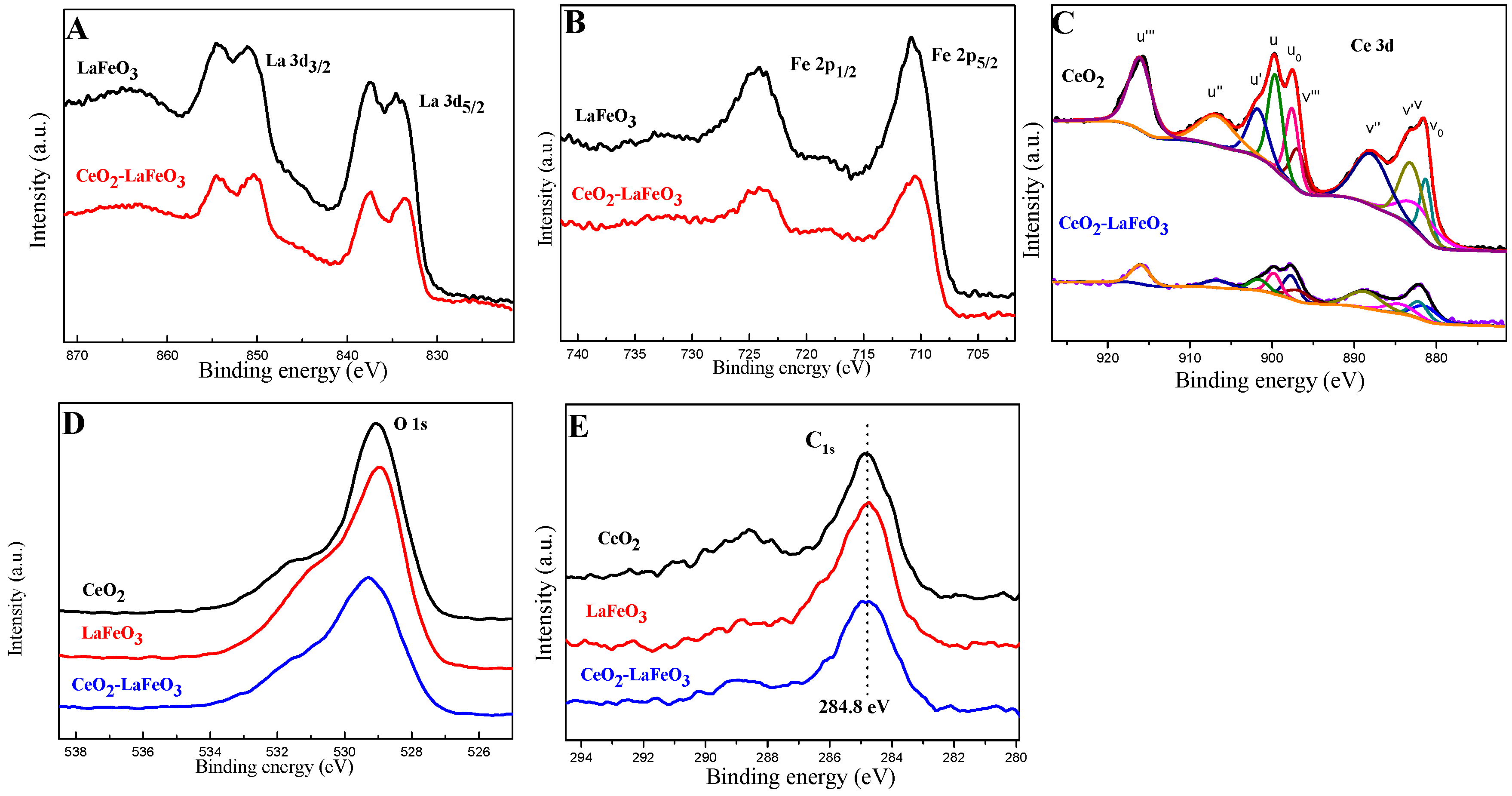

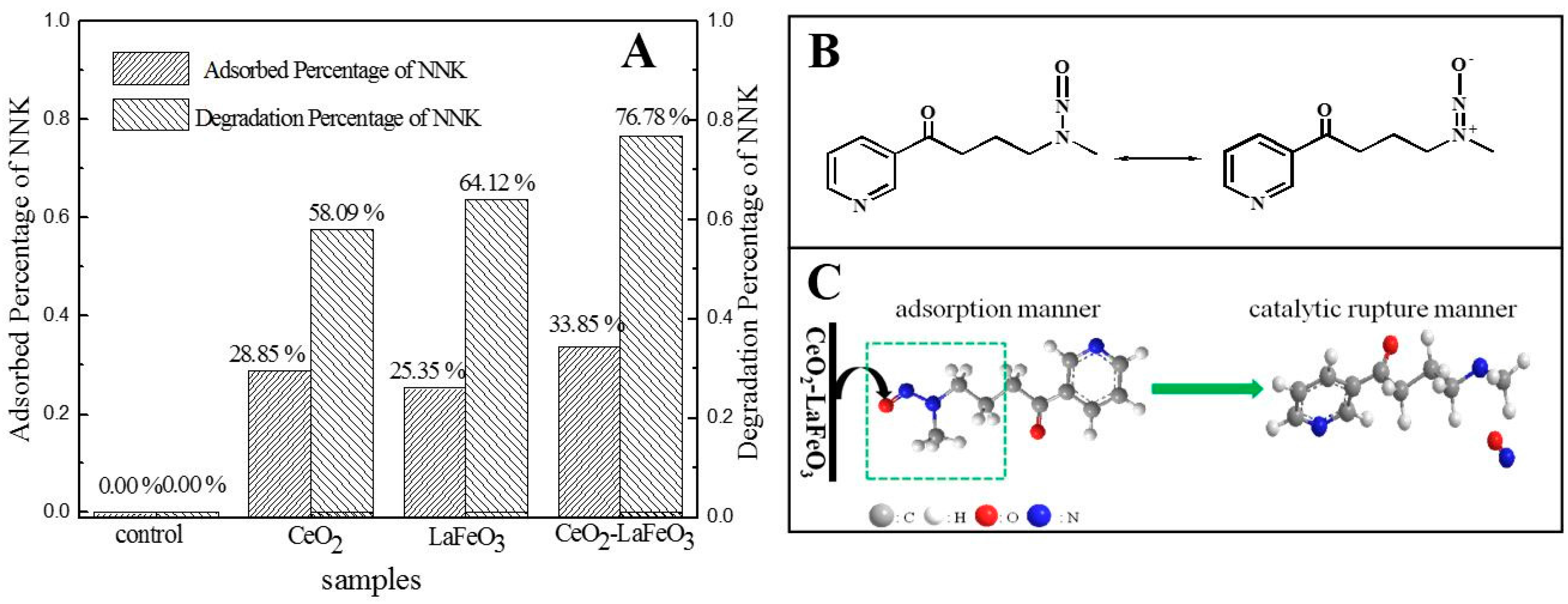

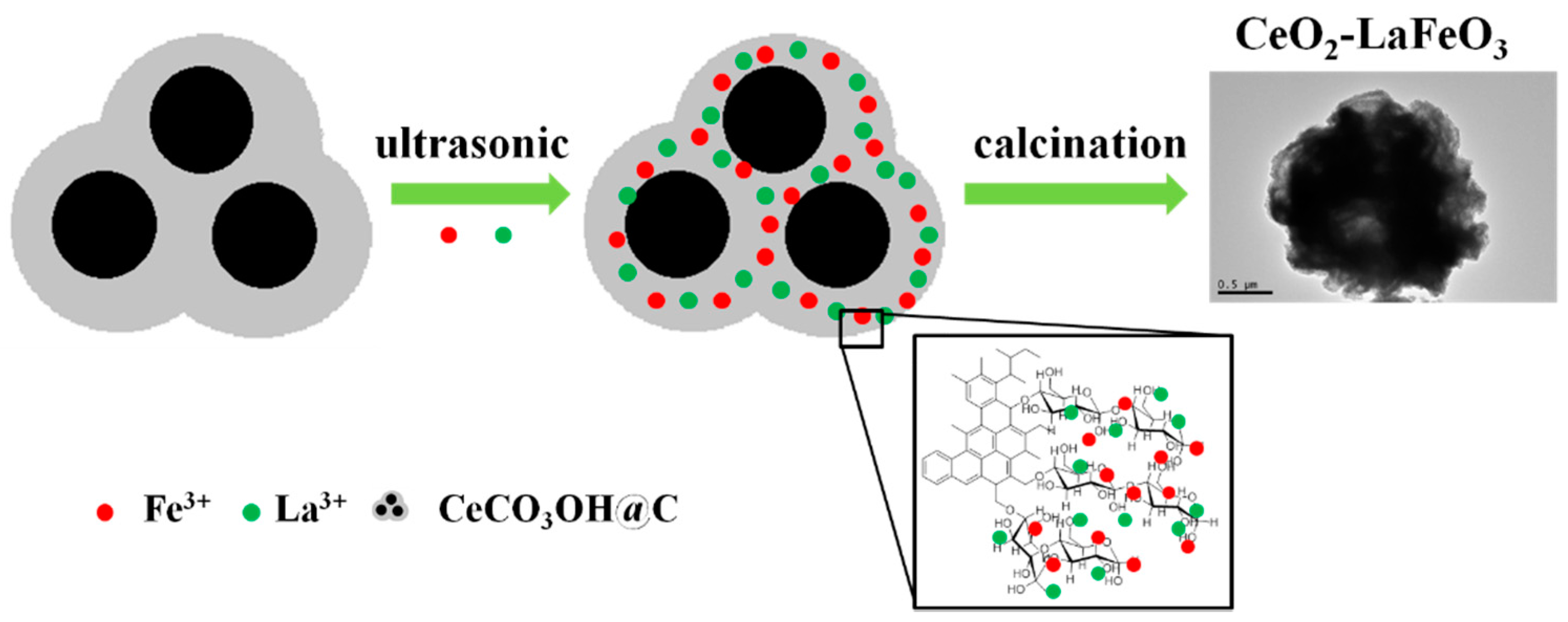

2. Results and Discussion

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Materials

3.2. Synthesis

3.3. Degradation of 4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-Pyridyl)-1-Butanone (NNK) by CeO2-LaFeO3

3.4. Characterization

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Royer, S.; Duprez, D.; Can, F.; Courtois, X.; Batiot-Dupeyrat, C.; Laassiri, S.; Alamdari, H. Perovskites as Substitutes of Noble Metals for Heterogeneous Catalysis: Dream or Reality. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 10292–10368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.J.; Li, H.L.; Zhong, L.Y.; Xiao, P.; Xu, X.L.; Yang, X.G.; Zhao, Z.; Li, J.L. Perovskite Oxides: Preparation, Characterizations, and Applications in Heterogeneous Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 2917–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimakawa, Y.; Azuma, M.; Ichikawa, N. Multiferroic Compounds with Double-Perovskite Structures. Materials 2011, 4, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mefford, J.T.; Hardin, W.G.; Dai, S.; Johnston, K.P.; Stevenson, K.J. Anion charge storage through oxygen intercalation in LaMnO3 perovskite pseudocapacitor electrodes. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.J.; Xu, D.; Wang, Z.L.; Wang, H.G.; Zhang, L.L.; Zhang, X.B. Synthesis of Perovskite-Based Porous La0.75Sr0.25MnO3 Nanotubes as a Highly Efficient Electrocatalyst for Rechargeable Lithium Oxygen Batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 3887–3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artem, M.; Marina, R.; Alexander, B.; Alexander, G. Nanocrystalline BaSnO3 as an Alternative Gas Sensor Material: Surface Reactivity and High Sensitivity to SO2. Materials 2015, 8, 6437–6454. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Zhang, R.D.; Chen, B.H.; Bion, N.; Duprez, D.; Hou, L.W.; Zhang, H.; Royer, S. Design of nanocrystalline mixed oxides with improved oxygen mobility: A simple non-aqueous route to nano-LaFeO3 and the consequences on the catalytic oxidation performances. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 4923–4925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.J.; Wang, Z.L.; Xu, D.; Meng, F.Z.; Zhang, X.B. 3D ordered macroporous LaFeO3 as efficient electrocatalyst for Li-O2 batteries with enhanced rate capability and cyclic performance. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 2213–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.L.; Li, M.J.; Overbury, S.H. On the structure dependence of CO oxidation over CeO2 nanocrystals with well-defined surface planes. J. Catal. 2012, 285, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.L.; Huang, B.C.; Wang, W.H.; Wei, Z.L.; Ye, D.Q. Low-temperature SCR of NO with NH3 over CeO2 supported on modified activated carbon fibers. Catal. Commun. 2011, 12, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.J.; Chen, D.H.; Chen, L. Synthesis of monodisperse CeO2 hollow spheres with enhanced photocatalytic activity. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 11570–11575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.P.; Zhao, L.H.; Teng, B.T.; Lang, J.J.; Hu, X.; Li, T.; Fang, Y.A.; Luo, M.F.; Lin, J.J. Catalytic combustion of methane on La1−xCexFeO3 oxides. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 276, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stathopoulos, V.N.; Belessi, V.C.; Bakas, T.V.; Neophytides, S.G.; Costa, C.N.; Pomonis, P.J.; Efstathiou, A.M. Comparative study of La-Sr-Fe-O perovskite-type oxides prepared by ceramic and surfactant methods over the CH4 and H2 lean-deNOx. Appl. Catal. B 2009, 93, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, T.H.; Ida, S.; Ishihara, T. Doped CeO2-LaFeO3 Composite Oxide as an Active Anode for Direct Hydrocarbon-Type Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 19399–19407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shikha, P.; Kang, T.S.; Randhawa, B.S. Effect of different synthetic routes on the structural, morphological and magnetic properties of Ce doped LaFeO3 nanoparticles. J. Alloy. Compd. 2015, 625, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Hla, S.S.; Duffy, G.J.; Cousins, A.J.; French, D.; Morpeth, L.D.; Edwards, J.H.; Roberts, D.G. Effect of Ce on the structural features and catalytic properties of La(0.9−x)CexFeO3 perovskite-like catalysts for the high temperature water-gas shift reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.M.; Sun, K.N.; Li, X.K.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.B.; Zhang, N.Q.; Zhou, X.L. A novel doped CeO2-LaFeO3 composite oxide as both anode and cathode for solid oxide fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 12574–12579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Bernert, J.T. Stability of the Tobacco-Specific Nitrosamine 4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-Pyridyl)-1-Butanol in Urine Samples Stored at Various Temperatures. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2010, 34, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.G.; Zhou, Y.; Gu, F.N.; Zhou, S.L.; Zhu, J.H. Catalytic degradation of tobacco-specific nitrosamines by ferric zeolite. Appl. Catal. B 2013, 129, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.H.; Gao, F.Q.; Flagg, T.; Deng, X.M. Nicotine induces multi-site phosphorylation of bad in association with suppression of apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 23837–23844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.J.; Yang, T.; Li, X.; Xia, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zou, F.; Jiang, Y.G. 4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-Pyridyl)-1-Butanone Induces Circulating MicroRNA Deregulation in Early Lung Carcinogenesis. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2014, 27, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.Z.; Wang, R.Y.; Bush, L.P.; Zhou, J.; Yang, H.J.; Fannin, N.; Bai, R.S. Changes in TSNA Contents during Tobacco Storage and the Effect of Temperature and Nitrate Level on TSNA Formation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 6, 11588–11594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.Y.; Wan, M.M.; Zhu, J.H. Cleaning carcinogenic nitrosamines with zeolites. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2014, 12, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.X.; Huang, C.Z.; Zhang, J.P.; Xie, W.; Xu, H.C.; Wei, M.D. Selectively reduction of tobacco specific nitrosamines in cigarette smoke by use of nanostructural titanates. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 5519–5523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.M.; Gao, W.L.; Zhang, J. Facile synthesis of monodispersed CeO2 nanostructures. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2011, 72, 1472–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, D.H.; Huang, K.C. Characterizations of Gd(Fe1−xInx)O3 films prepared by chemical solution deposition. Electrochem. Solid State Lett. 2007, 10, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullity, B.D.; Stock, S.R. Elements of X-ray Diffraction; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 385–433. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.M.; Li, Y.D. Colloidal carbon spheres and their core/shell structures with noble-metal nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.Y.; Niu, H.L.; Fu, S.S.; Song, J.M.; Mao, C.J.; Zhang, S.Y.; Zhang, D.W.; Chen, C.L. Core-shell CeO2@C nanospheres as enhanced anode materials for lithium ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 6790–6795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, G.S.; Alzate, N.M.; Arnache, O. A novel LaFeO3−XNX oxynitride. Synthesis and characterization. J. Alloy. Compd. 2013, 549, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noroozifar, M.; Khorasani-Motlagh, M.; Ekrami-Kakhki, M.S.; Khaleghian-Moghadam, R. Enhanced electrocatalytic properties of Pt-chitosan nanocomposite for direct methanol fuel cell by LaFeO3 and carbon nanotube. J. Power Sources 2014, 248, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gong, L.; Li, Y.B.; Wei, Z.X. Combustion synthesis of La0.8Sr0.2MnO3 and its effect on HMX thermal decomposition. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2010, 18, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinaeva, L.G.; Isupova, L.A.; Prosvirin, I.P.; Sadovskaya, E.M.; Danilova, I.G.; Ivanov, D.V.; Gerasimov, E.Y. La-Fe-O/CeO2 Based Composites as the Catalysts for High Temperature N2O Decomposition and CH4 Combustion. Catal. Lett. 2013, 143, 1294–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phokha, S.; Pinitsoontorn, S.; Maensiri, S.; Rujirawat, S. Structure, optical and magnetic properties of LaFeO3 nanoparticles prepared by polymerized complex method. J. Sol Gel Sci. Technol. 2014, 71, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.D.; Jayavel, R. Facile hydrothermal synthesis and characterization of LaFeO3 nanospheres for visible light photocatalytic applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2014, 25, 3953–3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concepcion, P.; Corma, A.; Silvestre-Albero, J.; Franco, V.; Chane-Ching, J.Y. Chemoselective hydrogenation catalysts: Pt on mesostructured CeO2 nanoparticles embedded within ultrathin layers of SiO2 binder. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 5523–5532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.X.; Xu, Y.Q.; Liu, H.Y.; Hu, C.W. Preparation and catalytic activities of LaFeO3 and Fe2O3 for HMX thermal decomposition. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 165, 1056–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Yang, J.Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wei, F.; Lin, W.G.; Zhu, J.H. Hierarchical functionalized MCM-22 zeolite for trapping tobacco specific nitrosamines (TSNAs) in solution. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 179, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.G.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhou, S.L.; Wan, M.M.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.H. Applying heterogeneous catalysis to health care: In situ elimination of tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNAs) in smoke by molecular sieves. Catal. Today 2013, 212, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.S.; Niu, H.L.; Tao, Z.Y.; Song, J.M.; Mao, C.J.; Zhang, S.Y.; Chen, C.L.; Wang, D. Low temperature synthesis and photocatalytic property of perovskite-type LaCoO3 hollow spheres. J. Alloy. Compd. 2013, 576, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Fe | Ce | La | O | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CeO2 | - | 22.14 | - | 52.01 | 25.85 |

| LaFeO3 | 17.01 | - | 14.19 | 51.6 | 17.2 |

| CeO2-LaFeO3 | 13.58 | 9.3 | 10.1 | 49.47 | 17.55 |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, K.; Niu, H.; Chen, J.; Song, J.; Mao, C.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, S.; Liu, B.; Chen, C. Facile Synthesis of CeO2-LaFeO3 Perovskite Composite and Its Application for 4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-Pyridyl)-1-Butanone (NNK) Degradation. Materials 2016, 9, 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9050326

Wang K, Niu H, Chen J, Song J, Mao C, Zhang S, Zheng S, Liu B, Chen C. Facile Synthesis of CeO2-LaFeO3 Perovskite Composite and Its Application for 4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-Pyridyl)-1-Butanone (NNK) Degradation. Materials. 2016; 9(5):326. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9050326

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Kaixuan, Helin Niu, Jingshuai Chen, Jiming Song, Changjie Mao, Shengyi Zhang, Saijing Zheng, Baizhan Liu, and Changle Chen. 2016. "Facile Synthesis of CeO2-LaFeO3 Perovskite Composite and Its Application for 4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-Pyridyl)-1-Butanone (NNK) Degradation" Materials 9, no. 5: 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9050326

APA StyleWang, K., Niu, H., Chen, J., Song, J., Mao, C., Zhang, S., Zheng, S., Liu, B., & Chen, C. (2016). Facile Synthesis of CeO2-LaFeO3 Perovskite Composite and Its Application for 4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-Pyridyl)-1-Butanone (NNK) Degradation. Materials, 9(5), 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9050326