1. Introduction

With a rapid increase in population worldwide, demand for energy, mostly from combustion of fossil fuels, is raised dramatically. Consequently, the atmospheric concentrations of several greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrous oxide (N2O), and methane (CH4) have increased by around 40% since the large-scale industrialization began in the early 19th century, leading to global warming and severe climate change. In addition, soot and fine particulate matters associated with the combustion of fossil fuels have been released into the atmosphere every year and have thus threatened the lives of many humans. Furthermore, the ecological balance on earth will also be destroyed if such problems are not resolved as early as possible. Therefore, the research and development of sustainable energy have been extensively carried out worldwide.

Hydrogen energy plays quite an important role in terms of sustainable energy. For example, the hydrogen gases can react with oxygen to generate electric power in fuel cells. Alternatively, the fuel cell can directly convert chemical energy into electricity, accompanied with the generation of water and heat. Among various types of fuel cells, the proton-exchange-membrane fuel cell (PEMFC) possesses some attractive advantages, for instance, lower operating temperature, more compact, lower weight, sustained operation at a higher current density, longer stack life, quicker start-up, suitability to discontinuous operation, and potential for a lower operation cost and volume [

1]. However, for the longer operation duration of PEMFC, a stable supply of ultrapure hydrogen is necessary. Therefore, the development of an applicable hydrogen storage and supply technology attracts enormous attention.

No viable hydrogen storage method has been commercialized so far owing to many limitations such as the size, weight and cost. To overcome the barriers mentioned above, the hydrogen supplied to the PEMFC would be preferentially produced on site and on demand. In addition to the hydrogen production techniques, other topics such as an efficient distribution and storage of the hydrogen should be taken into account as well in order to realize the hydrogen economy. For example, the hydrogen storage and supply is a critical issue in the automobile on-board system, on which a higher volumetric and gravimetric energy density but the smaller size and the less weight of the container for the hydrogen storage are desired.

Among various H

2 storage methods, chemical hydride fuel systems, composed of lighter elements than metal hydrides, exhibit the higher gravimetric hydrogen density. Release of hydrogen from chemical hydrides can be mostly divided into two ways, inclusive of pyrolysis reaction and hydrolysis method. The representative reactions of the hydrolysis reaction are shown in the Equations (1) and (2).

where

M is a metal and

y is the valence of metal [

2].

where

M is an alkali metal (Group IA), and

X for a trivalent element from Group IIIA [

2].

Chemical hydrides such as LiBH

4, NaBH

4, KBH

4, LiH, NaH, and MgH

2 can react with water at an ambient condition with/without the presence of suitable catalysts, leading to the generation of hydrogen of high purity with no CO evolved, which can be directly fed into the fuel cell system without any prior purification required. In contrast, the hydrogen gas produced from the steam reforming methods contains inevitably a significant level of CO and has to undergo the purification measure before being consumed in the PEMFCs. Notably, the metal borohydrides are considered the better candidates for the hydrogen storage system because of their high storage capacity [

3]. Moreover, among different metal borohydrides, NaBH

4 is regarded as one having a higher potential to meet the goals declared by the US DOE because of its higher hydrogen content (

i.e., 10.8 wt%) through the hydrolysis reaction as follows [

4]:

Nevertheless, with relentless effort numerous works have been conducted in developing suitable catalysts to promote the H

2 generation from aqueous NaBH

4 systems. Still, existence of the intrinsic defects in the aqueous NaBH

4 systems, such as poor aqueous solubility of spent borohydride—metaborate—restricts their progress in practical applications. For example, instead of the ideal condition presented in Equation (3), the poorer aqueous solubility of the sodium metaborate, produced along with the evolution of the hydrogen gas from the hydrolysis of the NaBH

4 shown in Equation (3), often results in solid precipitates on catalysts, blocking the active catalytic sites for the subsequent hydrolysis reaction of NaBH

4 to produce hydrogen. Furthermore, not all hydrogen atoms in water molecules involved in the hydrolysis of NaBH

4 are transformed into the produced hydrogen gas. Instead, many of them are rather taken up by the metaborate molecules to form various types of hydrates, as shown in Equation (4) [

5], and, hence, the gravimetric storage density of the hydrogen in such a chemical hydride fuel system is decreased.

As a result, the hydrogen storage capacity in an aqueous NaBH

4 system would generally decrease from theoretically predicted 10.8 wt% to 7.5 wt%, when the aqueous solubility of NaBH

4,

i.e., 55 g NaBH

4 per 100 g H

2O or equivalently 35.48 wt% at 25 °C, is considered. Furthermore, if taking the aqueous solubility of NaBO

2,

i.e., 28 g NaBO

2 per 100 g H

2O at 25 °C, into account, NaBO

2 becomes a limiting reagent in the hydrolysis reaction of NaBH

4 for hydrogen generation. Consequently, the initial NaBH

4 concentration in the hydrogen generation system should not exceed 16 g NaBH

4 per 100 g H

2O at 25 °C in order to maintain a liquid state during the whole course of hydrogen production. Otherwise, the excess NaBO

2 produced would precipitate out on the catalyst surface and, hence, could seriously reduce the performance of hydrogen generation by deactivating the active sites of catalysts [

5]. Accordingly, the hydrogen storage capacity in an aqueous NaBH

4 system would further be decreased down to 2.9 wt% or even lower if any hydrated NaBO

2 is present. This is also one of the major reasons that the no-go decision of using NaBH

4 aqueous system for the onboard hydrogen storage was made by the US DOE in 2007, according to the test reports from Millennium Cell, ANL and TIAX laboratory [

6]. The other reason attributable to the No-Go decision is the high-energy penalty and cost of regenerating sodium metaborate (NaBO

2) back to NaBH

4 fuel [

6]. That is, the hydrogen cost and energy efficiency are of significant concern and need to be overcome to witness the realization of the chemical hydride fuel system.

In order to reduce the cost of the hydrogen evolved from the NaBH

4 fuel systems, a concept of utilizing water, instead of borohydrides, as a limiting agent in hydrogen production was recently proposed [

7,

8]. In brief, the presence of excess water has increased the total mass of the system and, thus, has reduced the total gravimetric and volumetric capacities of the hydrogen stored in such NaBH

4 fuel systems. That is, the hydrogen production from such a NaBH

4 hydrogen storage system mainly takes place in the solid phase or in the liquid phase in close proximity to the solid-liquid boundary. Therefore, the gravimetric storage capacity of hydrogen in the NaBH

4/H

2O system could be effectively enhanced. Liu

et al. [

7] and Gislon

et al. [

8] both pointed out that the effective H

2 storage capacities as high as 6.7 wt% and 6.5 wt%, respectively, could be achieved in such a solid NaBH

4 hydrogen storage system. Moreover, the gravimetric hydrogen storage capacity was further improved to

ca. 7.3 wt% from the solid-state NaBH

4/Ru-based catalyst composites prepared from a high-energy ball-milling process [

9]. This also implies that a superior H

2 storage capacity from the solid NaBH

4 hydrogen storage systems could possibly reach the set 2010 target of US DOE at 6 wt% for on-board system.

In addition to the on-board applications, NaBH

4 has been attempted to be applied to portable devices or the maintenance-free stationary systems, for instance, to be used in a cell phone charger, and to feed the fuel cells in the off-grid remote warning system because of its long shelf life. As aforementioned, besides the issue of the hydrogen storage capacity, the cost of NaBH

4 and the difficulty in recycling the spent-NaBH

4,

i.e., NaBO

2, back to the borohydride fuel are the main causes leading to the No-Go recommendation to the NaBH

4-based hydrogen storage system for the vehicle on-board applications [

6]. That is, the production cost of NaBH

4 is still posting a hurdle to its practical applications. In the subsequent sections of this report, the life cycle of the NaBH

4 is discussed in order to shed light on the strategy in alleviation of the production cost and recycling of the NaBH

4.

In order to increase the hydrogen storage capacity, NH

3BH

3 (commonly denoted as AB) has become the center of recent relevant studies [

10,

11,

12,

13], especially after the US DOE’s No-Go recommendation to NaBH

4 for on-board automotive hydrogen storage [

5,

6]. NH

3BH

3 (borazane) contains intrinsically 19.6 wt% hydrogen. Notably, the hydrogen storage capacity of NH

3BH

3 is generally accepted to possibly reach more than 9 wt%. More importantly, NH

3BH

3 and its spent products after hydrogen released via the hydrolysis reaction is rarely toxic, stable and easily handled at ambient conditions [

10,

11,

12,

13].

NH

3BH

3 is generally known to possess many advantages: (1) its long-term storage stability, for example, more than 80 days stable in aqueous solution under an argon atmosphere [

14], and (2) the smallest volume occupied for hydrogen supply, e.g., 13.32 mL for NH

3BH

3 in relative to 17.38 mL for NaBH

4 and 51.11 mL for compressed hydrogen at 70 MPa and 288 K to supply one mole of hydrogen. Explicitly, this makes NH

3BH

3 suitable as a hydrogen storage medium for on-board vehicle applications. In addition, hydrogen in great purity can be obtained from the hydrolysis reaction of NH

3BH

3 in presence of particular catalysts, including noble metals [

15,

16], transition metals [

14,

17], even acids and carbon dioxide [

10]. Alternatively, hydrogen can be liberated through the pyrolysis of NH

3BH

3 between 137 and 400 °C as well [

14,

18].

2. Life Cycle of Sodium Borohydride (NaBH4) and Ammonia Borane (NH3BH3)

The prevailing production method of NaBH

4 in industrial scale is the Brown-Schlesinger process [

4], which generally consists of seven steps [

19] that are schematically shown in

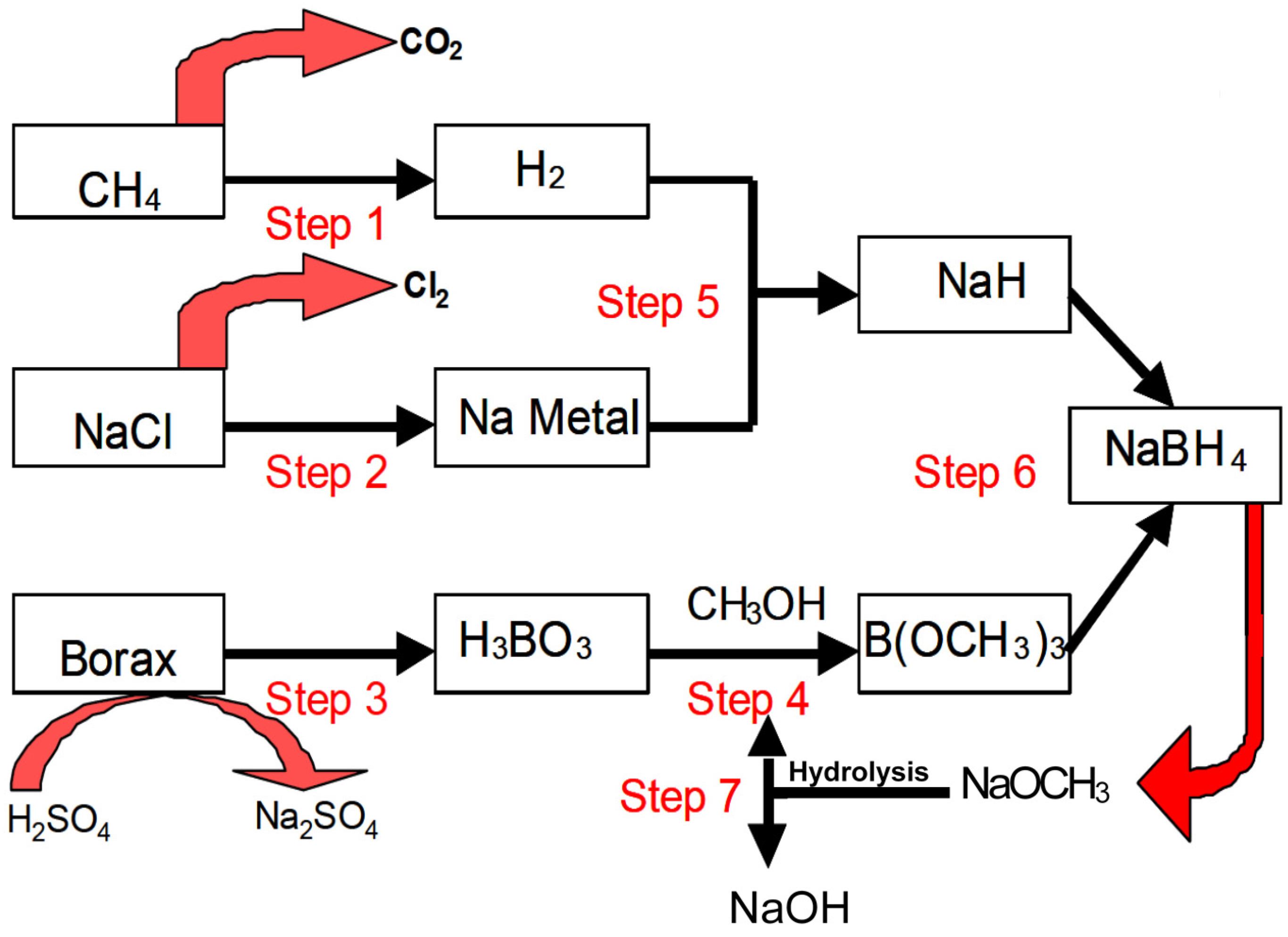

Figure 1 and described briefly as follows:

Step 1. Hydrogen produced from steam reforming of methane.

Step 2. Metallic sodium obtained through the electrolysis of sodium chloride.

Step 3. Boric acid converted from borax.

Step 4. Trimethyl borate synthesized from esterification of boric acid in methanol.

Step 5. Sodium hydride produced from metallic sodium reacting with hydrogen.

Step 6. Synthesis of NaBH4 via the reaction of trimethyl borate with sodium hydride.

Step 7. Methanol recycled from the hydrolysis of sodium methoxide.

Figure 1.

The Brown-Schlesinger process for the synthesis of NaBH

4 [

19].

Figure 1.

The Brown-Schlesinger process for the synthesis of NaBH

4 [

19].

The large-scale synthesis of NH

3BH

3 was first reported by Shore and Böddeker in 1964 [

20]. In brief, NH

3BH

3 was obtained by extraction with ether from the solid mixture resulted from diborane dispersed in tetrahydrofuran (THF) passed with ammonia at −78 °C, close to the melting point of ammonia at −77.73 °C [

20].

Recently, a simplified process close to the ambient condition is devised to synthesize NH

3BH

3 from NaBH

4 and ammonia sulfate in tetrahydrofuran at 40 °C shown as Equation (6), in contrast to −78 °C for the Shore-Böddeker process [

20].

Nonetheless, the NH3BH3 is still too expensive for practical applications. For example, according to the information supplied from Sigma-Aldrich, the current price tag for the NH3BH3 in technical grade with a purity of 90% is US$ 158.50 per 10 g, in contrast to US$ 201 per 500 g for NaBH4 with a purity >96%. Moreover, in view of NH3BH3 as a sustainable supply of hydrogen, it is desirable to regenerate the spent product of NH3BH3 after hydrogen production.

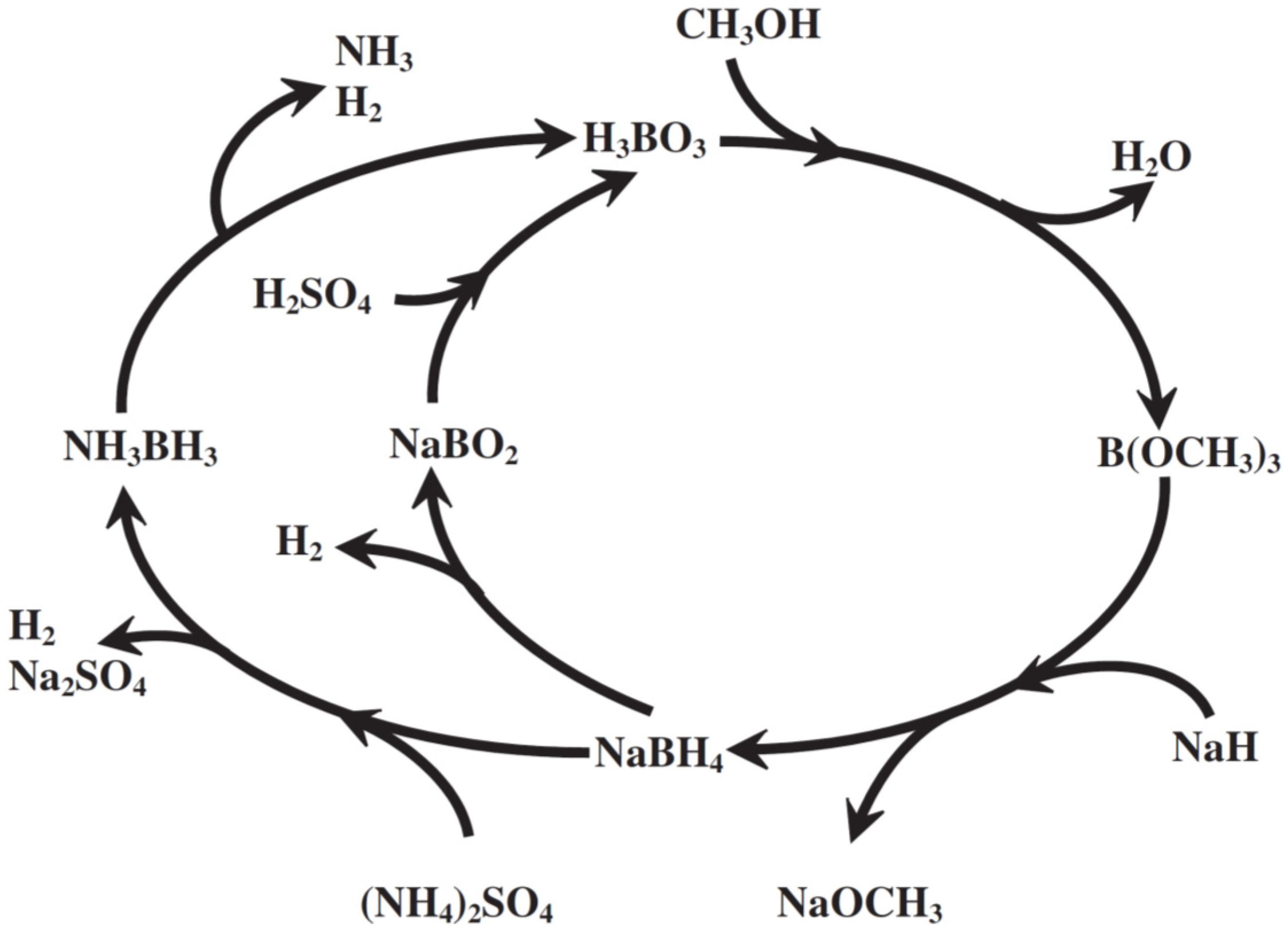

Previously, boric acid (H

3BO

3) was found to be one major product in the hydrolysate of NH

3BH

3 [

21]. Boric acid is likely resulted from the quick acidification of sodium metaborate (NaBO

2) in the presence of H

2SO

4 or in acidic condition [

21]. Notably, boric acid is one of the reactants used in the production of trimethyl borate (B(OCH

3)

3), a precursor of the NaBH

4 through the Brown-Schlesinger process [

22]. Subsequently, NaBH

4 could be fabricated by reacting trimethyl borate with sodium hydride (NaH) at 220–250 °C in oil bath with the Brown-Schlesinger process [

4]. Thus, the total life cycle between NH

3BH

3 (NH

3BH

3) and NaBH

4 for hydrogen generation could be sketched (

Figure 2), which illustrates the possible pathways in hydrogen production from these chemical hydrides. Furthermore, with the information shown in

Figure 2, the possible regeneration scheme of these spent chemical hydrides harvested from those after hydrogen evolution can be explored and investigated to shed a light to the realization of hydrogen economy by reducing the production cost of the NH

3BH

3. That is to say, once the cost of NaBH

4 could be reduced, less expensive NH

3BH

3 could be manufactured.

Figure 2.

The proposed total life cycle of borohydrides for hydrogen generation [

22].

Figure 2.

The proposed total life cycle of borohydrides for hydrogen generation [

22].

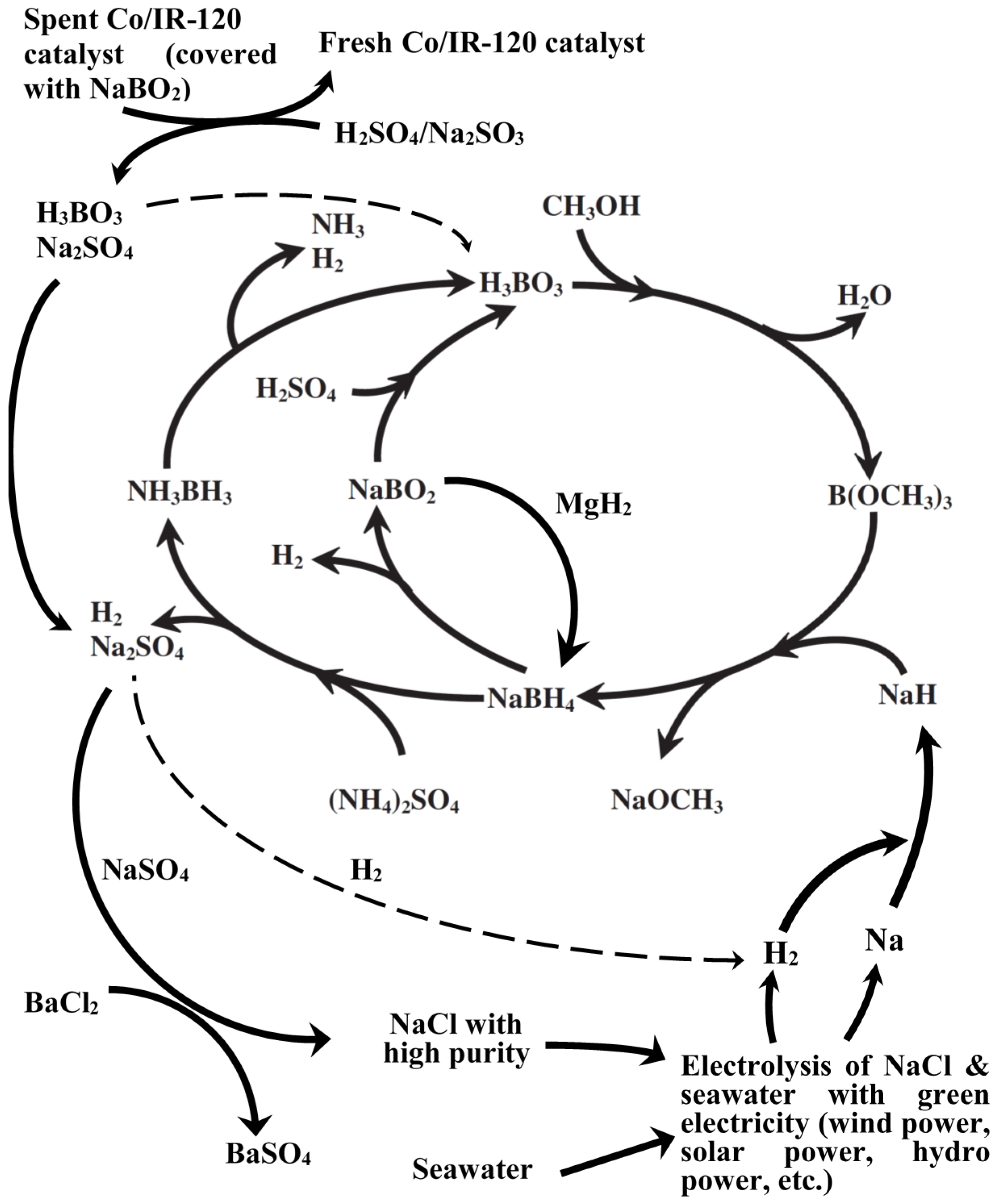

Among various production steps in the Brown-Schlesinger process, the one consuming the most energy is undoubtedly the electrolysis of NaCl to produce metallic sodium. The NaCl come from evaporation of seawater in the saltern, where the offshore wind farm is closely located. Moreover, metallic sodium is so active that occupies high cost during transportation with great care. Therefore, the in-house production of metallic sodium and sodium hydride will benefit the reduction in the production cost of NaBH4 as well as NH3BH3.

In this report, we will provide several possible solutions for the reduction in the production cost and the hazard and risk in the Brown-Schlesinger process either by the combination of green energy (

i.e., offshore wind power) and the electrolysis from seawater for the localized production of H

2 and NaH. The revised life cycle of NaBH

4-NH

3BH

3 will be presented accordingly in

Figure 3 and discussed in the following section.

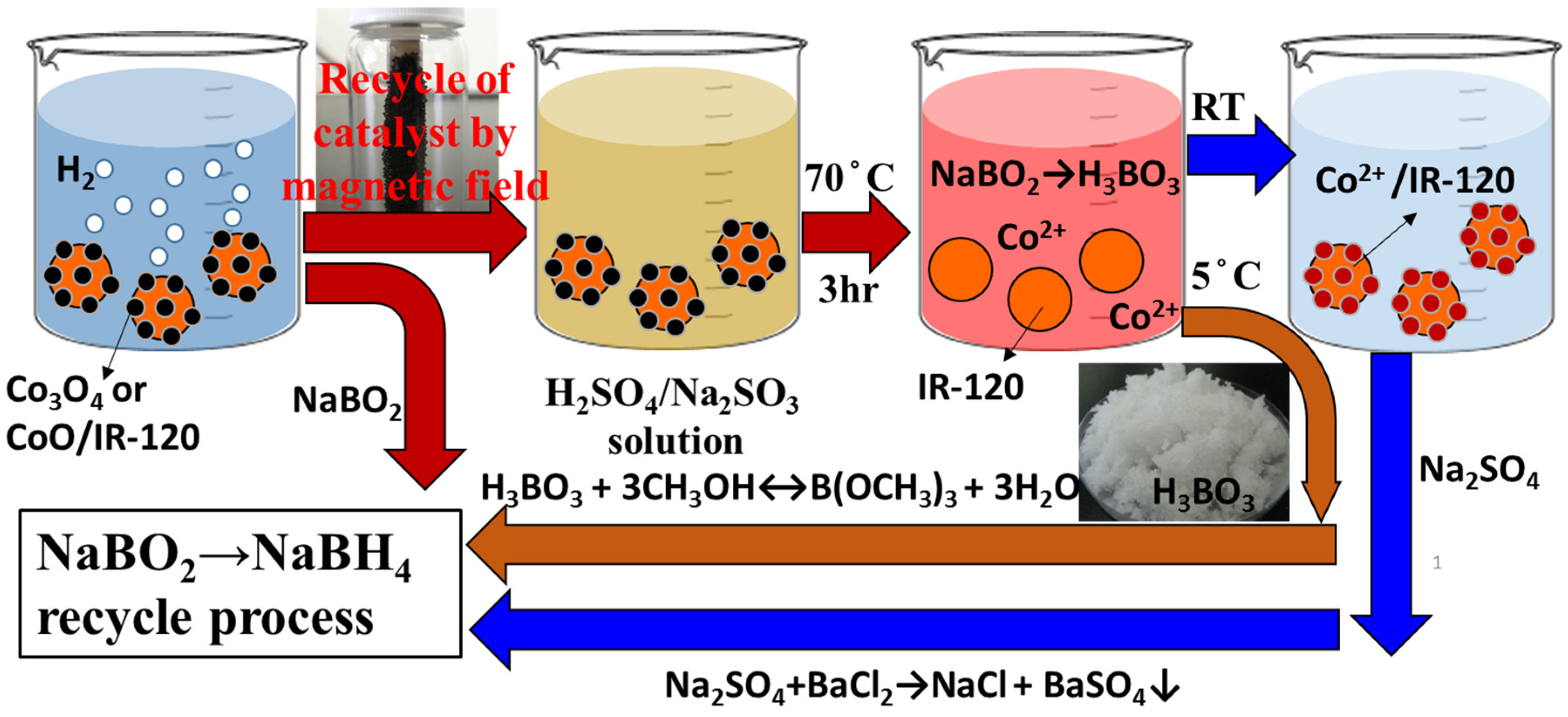

4. Recycle and Regeneration of Used Cobalt Catalysts

The used catalysts are recycled and regenerated not only for the sake of the economics consideration but also the sustainability. Previously, the magnetic cobalt catalysts loaded on the resin beads (Co/IR-120) have been successfully synthesized and applied to catalyze the hydrolysis of NaBH

4 in alkaline solution for hydrogen evolution [

24]. Not only a high production rate of hydrogen, but also the easiness in the recovery of the used Co/IR-120 from reacting system with permanent magnet was achieved [

24]. The surface chemistry of the prepared Co/IR-120 catalysts, made from the reduction of chelated cobalt ions on polymer resin by NaBH

4, was found mainly as cobalt oxides (Co

3O

4 and CoO), but not cobalt borides (Co

2B), according to the XPS analyses [

24]. With this information, a recycling process of the spent Co/IR-120 catalysts was devised for the simultaneous recycling and regeneration process to the spent-NaBH

4 and the used catalysts (

Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The combined concept of the regeneration processes of the spent-NaBH4 and the spent catalyst.

Figure 4.

The combined concept of the regeneration processes of the spent-NaBH4 and the spent catalyst.

In general, NaBO

2 is one major component of the spent-NaBH

4 and has a relatively lower solubility,

i.e., 28 g in 100 mL H

2O at 25 °C, than NaBH

4. Thus, NaBO

2 will precipitate on the surface of catalysts after the long-term hydrolysis reaction of NaBH

4 in concentrated solutions, leading to the deactivation of the catalyst. Notably, CoO could dissolve easily in H

2SO

4 solution (Equation (7)). However, the solubility of Co

3O

4 was much lower than that of CoO because Co

3O

4 is more stable than CoO [

25]. Fortunately, this problem can be resolved with the assistance of sulfite (SO

32−) that will facilitate the conversion of Co

3+ to Co

2+. The reduction-dissolution of Co

3O

4 can be presented as Equation (8), accordingly.

Consequently, the used Co/IR-120 catalyst after the hydrolysis reaction of NaBH

4 could be recycled conveniently with magnets and, then, immersed in the H

2SO

4/Na

2SO

3 solution at an appropriate concentration and temperature (

i.e., 70 °C for 3 h), shown in

Figure 4. During the immersion procedure, Co

2+ ion will be leached out from the surface of Co/IR-120 catalyst, while H

3BO

3 can be simultaneously obtained from NaBO

2 precipitated on catalyst with acids (Equation (9)).

The boric acid could be easily separated from the reacting mixture by crystallization at a lower temperature. For example, being cooled to 5 °C, needle-like H

3BO

3 crystal appears and precipitates out from the coexisting Na

2SO

4(aq) [

22]. Thus, boric acid could be conveniently collected through filtration. The boric acid will be, subsequently, esterified with excess methanol to yield trimethyl borate [

22], which can be further converted to NaBH

4 with NaH, according to the commercial Brown-Schlesinger process. Besides, the fresh Co

2+ ions can be chelated with the benzenesulfonyl groups on the IR-120 ion exchange resin beads again to generate the fresh Co/IR-120 catalysts to complete the regeneration process of the used catalyst.

The rest left in the solution after filtering-out H

3BO

3 crystals is dominantly the Na

2SO

4. BaCl

2 can be introduced to precipitate out BaSO

4 and to leave NaCl in the solution phase (

Figure 3). Finally, Na metal and hydrogen gas can be obtained from the electrolysis of the NaCl solution with the green electricity, Namely, the introduction of the green electricity to the recycling and regeneration processes of the spent borohydrides and NH

3BH

3 as well as the used catalysts could increase the sustainability of the chemical hydride H

2-fuel system and, therefore, realize the hydrogen economy.