Low-Field NMR for Carbon-Modified Cements: Dispersion and Hydration Studies

Highlights

- Improved colloidal stability of carbon black into water is revealed in the presence of an acrylic-based superplasticizer at SP/CB weight ratios between 0.1 and 2.

- During the in situ NMR mixing of carbon ink with cement, the peak ascribed to the carbon ink decreases with water content and paste mixing time.

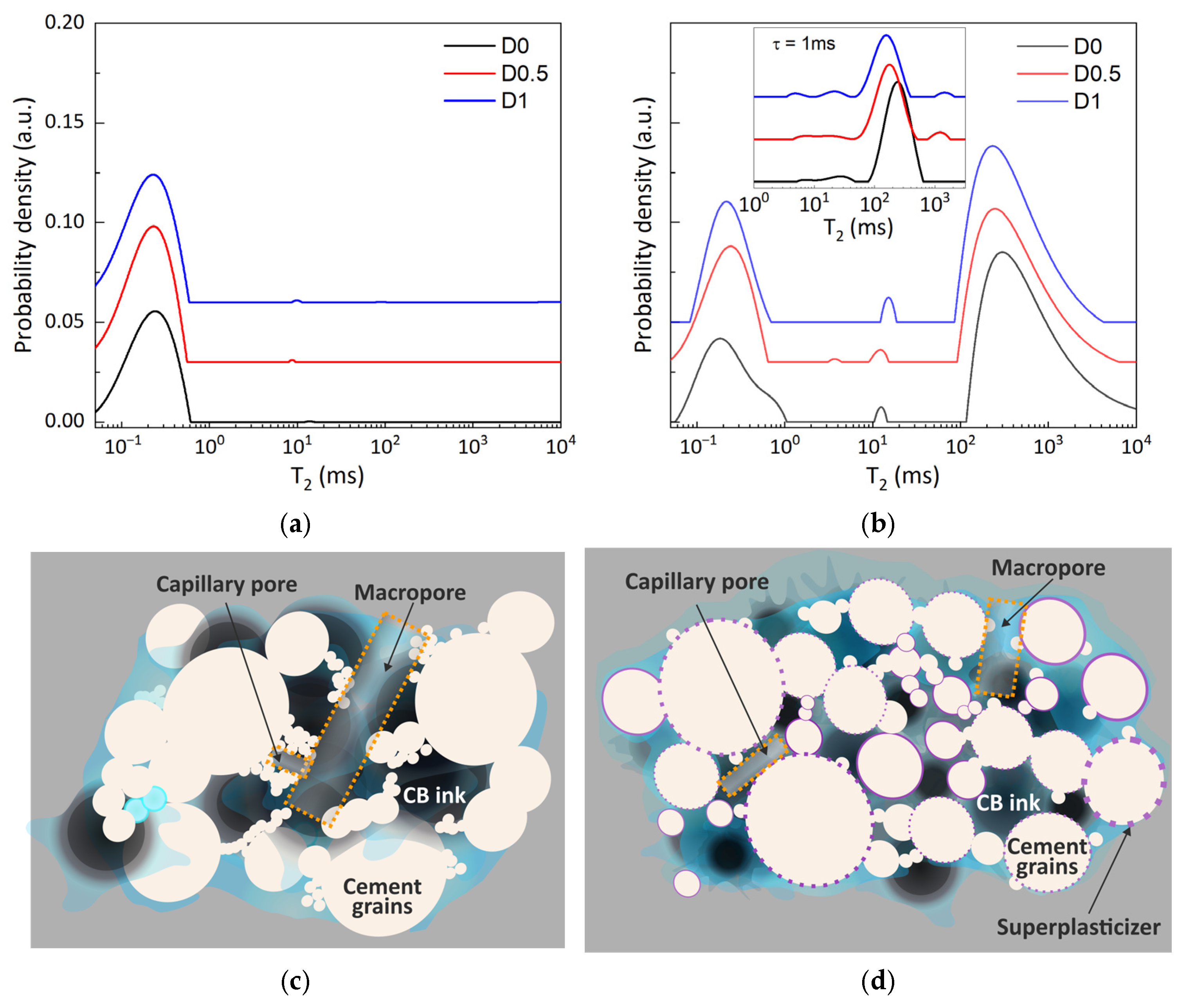

- In fresh cement pastes, an increase in superplasticizer dosage induced smaller initial transverse relaxation times and slower evolutions in the relaxation rate, indicating improved dispersion of cement particles and slower structural build-up.

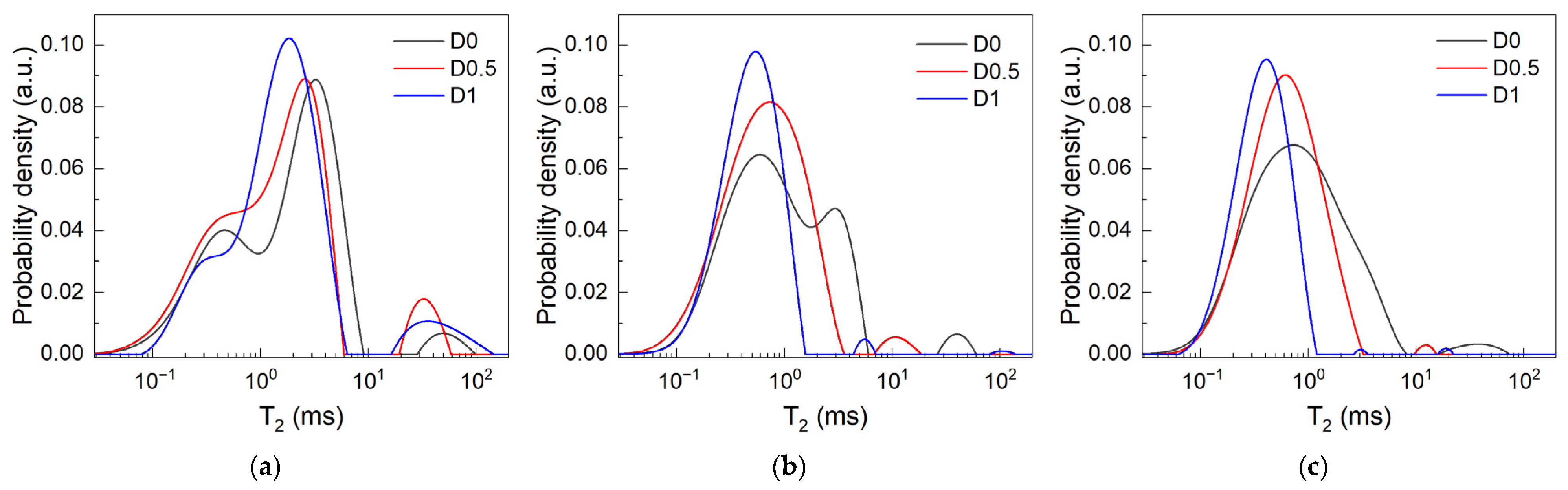

- In hardened cements, the increase in superplasticizer dosage induced more narrow relaxation time distributions and shorter relaxation times, indicators of a more refined pore network.

- They open new approaches in the characterization of carbon-containing cementitious composites that are non-contact and compatible with hydrated and hardened paste samples and allow a lower consumption of carbon materials during research stages.

- They further clarify the impact of the carbon black-dispersant role over cement hydration and microstructure.

- They contribute to the developing research interface between fundamental studies on cement, multifunctional carbon-integrated composites, and fields including smart buildings and additive manufacturing.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. Characterization Techniques

2.3.1. Dispersion, Stability, and DLS ζ-Potential Tests

2.3.2. NMR Relaxometry Experiments

2.3.3. Optic Microscopy

2.3.4. Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity (UPV) Tests

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Dispersion and Stability

3.2. Low-Field NMR Measurements at Different Hydration Stages

3.2.1. In Situ NMR Tests on the Effect of w/c Ratio

3.2.2. NMR and the Effects Introduced by SP Dosage During Early Hydration

3.2.3. NMR During the Hardening Stage

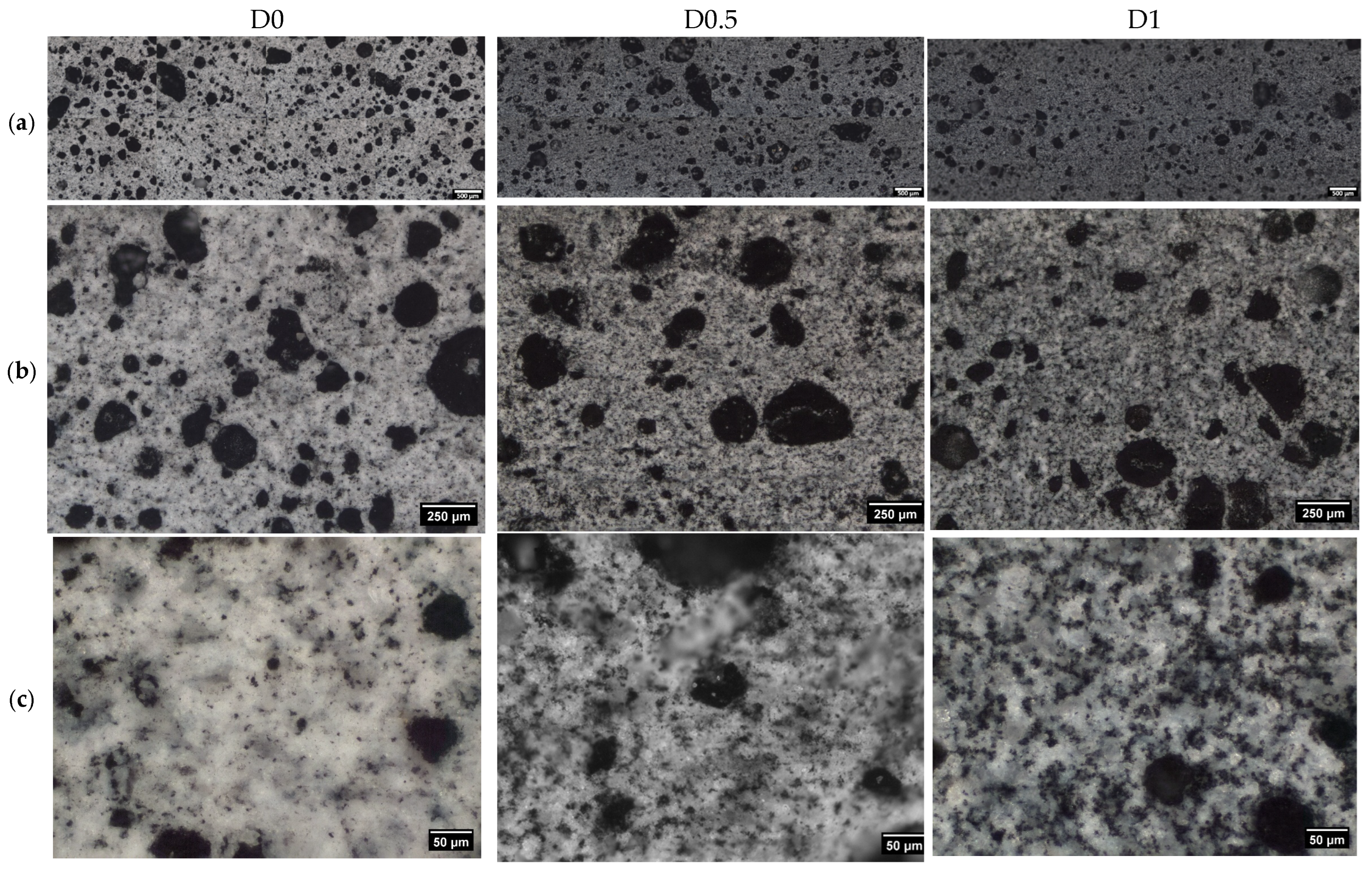

3.3. OM and UPV Tests

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| CB | Carbon Black |

| SP | Superplasticizer |

| WPC | White Portland Cement |

| DLS | Dynamic Light Scattering |

| OM | Optical Microscopy |

| UPV | Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity |

| CPMG | Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill |

| CSH | Calcium Silicate Hydrate |

| PDI | Polydispersity Index |

References

- Scrivener, K.; Ouzia, A.; Juilland, P.; Kunhi Mohamed, A. Advances in Understanding Cement Hydration Mechanisms. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 124, 105823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Leng, Z.; Lu, G.; Wang, D.; Huo, Y. A Critical Review of Carbon Materials Engineered Electrically Conductive Cement Concrete and Its Potential Applications. Int. J. Smart Nano Mater. 2023, 14, 189–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudente, I.N.R.; dos Santos, H.C.; Fonseca, J.L.; de Almeida, Y.A.; Gimenez, I.d.F.; Barreto, L.S. Graphene Family (GFMs), Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) and Carbon Black (CB) on Smart Materials for Civil Construction: Self-Cleaning, Self-Sensing and Self-Heating. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 95, 110175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinesh, A.; Indhumathi, S.; Pichumani, M. Self-Sensing Cement Composites for Structural Health Monitoring: From Know-How to Do-How. Autom. Constr. 2024, 160, 105304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Li, W.; Wang, K.; Shah, S.P.; Sheng, D. Multifunctional Cementitious Composites with Integrated Self-Sensing and Self-Healing Capacities Using Carbon Black and Slaked Lime. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 19851–19863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwon, S.; Kim, H.; Shin, M. Self-Heating Characteristics of Electrically Conductive Cement Composites with Carbon Black and Carbon Fiber. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 137, 104942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Aslani, F.; Mukherjee, A. Development of 3D Printable Self-Sensing Cementitious Composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 337, 127601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Lau, D.; Chang, J. Advancements in Energy Harvesting through Building Materials: A Critical Review. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanut, N.; Stefaniuk, D.; Weaver, J.C.; Zhu, Y.; Shao-Horn, Y.; Masic, A.; Ulm, F.-J. Carbon–Cement Supercapacitors as a Scalable Bulk Energy Storage Solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2304318120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Gao, P.; Li, G.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Xu, X. Fabrication and Electrical Properties of Carbon Fiber, Graphite and Nano Carbon Black Conductive Cement-Based Composites. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 60, 104834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.D.; Gwon, S.; Choi, Y.C.; Shin, M. Self-Heating Performance of Cement Composites Devised with Carbon Black and Carbon Fiber: Roles of Superplasticizer and Silica Fume. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 108054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, N.; Ioannidou, K.; Divoux, T.; Backov, R.; Omran, M.; Nîrca, T.; Pellenq, R.J.-M. Nano-Carbon Black (NCB)-Dispersed Cement Composites: A Macro-to-Nano Investigation Revealing Trade-Offs between Electrical Conductivity and Mechanical Strength. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 489, 142246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Lv, T.; Qi, Y.; Hou, D.; Zhao, Q.; Dong, B. Enhancement of Nano Carbon Black-Filled Cement Paste with Different Dispersants: Hydration Mechanism and Electrothermal Performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 490, 142542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, A.; Rallini, M.; Ubertini, F.; Materazzi, A.L.; Kenny, J.M. Investigations on Scalable Fabrication Procedures for Self-Sensing Carbon Nanotube Cement-Matrix Composites for SHM Ap-plications. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 65, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalon, G.H.; Ribeiro, J.C.L.; de Araújo, E.N.D.; Pedroti, L.G.; de Carvalho, J.M.F.; Santos, R.F.; Aparecido-Ferreira, A. Effects of Different Kinds of Carbon Black Nanoparticles on the Piezoresistive and Mechanical Properties of Cement-Based Composites. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bligh, M.W.; d’Eurydice, M.N.; Lloyd, R.R.; Arns, C.H.; Waite, T.D. Investigation of Early Hydration Dynamics and Microstructural Development in Ordinary Portland Cement Using 1H NMR Relaxometry and Isothermal Calorimetry. Cem. Concr. Res. 2016, 83, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Sun, Z.; Yang, J.; Ji, Y. A Novel Method for Semi-Quantitative Analysis of Hydration Degree of Cement by 1H Low-Field NMR. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 141, 106329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, R.; Maruyama, I. Surface Area Development of Portland Cement Paste during Hydration: Direct Comparison with 1H NMR Relaxometry and Water Vapor/Nitrogen Sorption. Cem. Concr. Res. 2022, 157, 106805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardelean, I. The Effect of an Accelerator on Cement Paste Capillary Pores: NMR Relaxometry Investigations. Molecules 2021, 26, 5328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, V.; Janovics, R.; Péter Kertész, T.; Nemes, Z.; Fodor, T.; Bányai, I.; Kéri, M. State and Role of Water Confined in Cement and Composites Modified with Metakaolin and Additives. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 388, 122716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, A.; Bede, A.; Dudescu, M.C.; Popa, F.; Ardelean, I. Monitoring the Influence of Aminosilane on Cement Hydration Via Low-Field NMR Relaxometry. Appl. Magn. Reson. 2016, 47, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, M.M.; Faux, D.; Ardelean, I. Monitoring the Effect of Calcium Nitrate on the Induction Period of Cement Hydration via Low-Field NMR Relaxometry. Molecules 2023, 28, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnertová, E.; Slovák, V.; Zelenka, T.; Vaulot, C.; Delmotte, L. Carbonaceous Materials Porosity Investigation in a Wet State by Low-Field NMR Relaxometry. Materials 2022, 15, 9021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyul, D.; Kéri, M.; Novák, L.; Szabó, H.; Csík, A.; Bányai, I. NMR Characterization of Graphene Oxide-Doped Carbon Aerogel in a Liquid Environment. Gels 2025, 11, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kéri, M.; Nyul, D.; László, K.; Novák, L.; Bányai, I. Interaction of Resorcinol-Formaldehyde Carbon Aerogels with Water: A Comprehensive NMR Study. Carbon 2022, 189, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadar, C.; Ardelean, I. Surface Influence on the Rotational and Translational Dynamics of Molecules Confined inside a Mesoporous Carbon Xerogel. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2019, 57, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadar, C.; Cotet, C.; Baia, L.; Ardelean, I. Probing the Connectivity and Wettability of Carbon Aerogels and Xerogels via Low-Field NMR. Conf. Proc. 2017, 1917, 040006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hong, S.; Li, W.; Guo, S. Assessing the Dispersion Quality of Carbon Nanotubes Suspensions by Low Field Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 611, 012029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairhurst, D.; Cosgrove, T.; Prescott, S.W. Relaxation NMR as a Tool to Study the Dispersion and Formulation Behavior of Nanostructured Carbon Materials. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2016, 54, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porrelli, D.; Cok, M.; Abrami, M.; Bosi, S.; Prato, M.; Grassi, M.; Paoletti, S.; Donati, I. Evaluation of Concentration and Dispersion of Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes in Aqueous Media by Means of Low Field Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Carbon 2017, 113, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, G.E.S.; Nalon, G.H.; Santos, R.F.; Ribeiro, J.C.L.; de Carvalho, J.M.F.; Pedroti, L.G.; de Araújo, E.N.D. Microstructural Investigation of the Effects of Carbon Black Nanoparticles on Hydration Mechanisms, Mechanical and Piezoresistive Properties of Cement Mortars. Mater. Res. 2021, 24, e20200539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN197-1:2011; Cement—Part 1: Composition, Specifications and Conformity Criteria for Common Cements. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- Rusu, M.M.; Vilau, C.; Dudescu, C.; Pascuta, P.; Popa, F.; Ardelean, I. Characterization of the Influence of an Accelerator upon the Porosity and Strength of Cement Paste by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Relaxometry. Anal. Lett. 2023, 56, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.; Van Dam, T.; Sutter, L.; Fick, G. Integrated Materials and Construction Practices for Concrete Pavement; National Concrete Pavement Technology Center, Ed.; Part of In TransProject No 13-482; National Concrete Pavement Technology Center, Iowa State University: Ames, IA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Meiboom, S.; Gill, D. Modified Spin-Echo Method for Measuring Nuclear Relaxation Times. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1958, 29, 688–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataramanan, L.; Song, Y.Q.; Hurlimann, M.D. Solving Fredholm Integrals of the First Kind with Tensor Product Structure in 2 and 2.5 Dimensions. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2002, 50, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, M.M.; Ardelean, I. Relations Between the Printability Descriptors of Mortar and NMR Relaxometry Data. Materials 2025, 18, 3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, B.; Van De Ville, D.; Berent, J.; Sage, D.; Unser, M. Extended Depth-of-Focus for Multi-Channel Microscopy Images: A Complex Wavelet Approach. In Proceedings of the 2004 2nd IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging: Macro to Nano (IEEE Cat No. 04EX821), Arlington, VA, USA, 15–18 April 2004; pp. 660–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, E.; Hall, M.; Holmes, G.; Kirkby, R.; Pfahringer, B.; Witten, I.H.; Trigg, L. Weka-A Machine Learning Workbench for Data Mining. In Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery Handbook; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 1269–1277. [Google Scholar]

- Marchon, D.; Kawashima, S.; Bessaies-Bey, H.; Mantellato, S.; Ng, S. Hydration and Rheology Control of Concrete for Digital Fabrication: Potential Admixtures and Cement Chemistry. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 112, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, A.; Ardelean, I. Monitoring the Size Evolution of Capillary Pores in Cement Paste during the Early Hydration via Diffusion in Internal Gradients. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 77, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepišnik, J.; Ardelean, I. Usage of Internal Magnetic Fields to Study the Early Hydration Process of Cement Paste by MGSE Method. J. Magn. Reson. 2016, 272, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bede, A.; Scurtu, A.; Ardelean, I. NMR Relaxation of Molecules Confined inside the Cement Paste Pores under Partially Saturated Conditions. Cem. Concr. Res. 2016, 89, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simina, M.; Nechifor, R.; Ardelean, I. Saturation-dependent Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Relaxation of Fluids Confined inside Porous Media with Micrometer-sized Pores. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2011, 49, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bede, A.; Ardelean, I. Revealing the Influence of Water-Cement Ratio on the Pore Size Distribution in Hydrated Cement Paste by Using Cyclohexane. AIP Conf. Proc. 2017, 1917, 040002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadar, C.; Cotet, C.; Baia, L.; Barbu-Tudoran, L.; Ardelean, I. Probing into the Mesoporous Structure of Carbon Xerogels via the Low-Field NMR Relaxometry of Water and Cyclohexane Molecules. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2017, 251, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, M.M.; Vulpoi, A.; Vilau, C.; Dudescu, C.M.; Păşcuţă, P.; Ardelean, I. Analyzing the Effects of Calcium Nitrate over White Portland Cement: A Multi-Scale Approach. Materials 2022, 16, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaiskos, G.; Deraemaeker, A.; Aggelis, D.G.; Hemelrijck, D. Van Monitoring of Concrete Structures Using the Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity Method. Smart Mater. Struct. 2015, 24, 113001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rusu, M.M.; Mostis, K.; Costinas, C.; Ardelean, I. Low-Field NMR for Carbon-Modified Cements: Dispersion and Hydration Studies. Materials 2026, 19, 528. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030528

Rusu MM, Mostis K, Costinas C, Ardelean I. Low-Field NMR for Carbon-Modified Cements: Dispersion and Hydration Studies. Materials. 2026; 19(3):528. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030528

Chicago/Turabian StyleRusu, Mihai M., Karoly Mostis, Codrut Costinas, and Ioan Ardelean. 2026. "Low-Field NMR for Carbon-Modified Cements: Dispersion and Hydration Studies" Materials 19, no. 3: 528. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030528

APA StyleRusu, M. M., Mostis, K., Costinas, C., & Ardelean, I. (2026). Low-Field NMR for Carbon-Modified Cements: Dispersion and Hydration Studies. Materials, 19(3), 528. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030528