Effects of Synthetic Fibers and Rubber Powder from ELTs on the Rheology of Mineral Filler–Bitumen Compositions

Highlights

- End-of-life tire (ELT) fibers and rubber powder enhance asphalt mastic rheology.

- Combined use of ELT fiber and rubber increases high-temperature stiffness and elasticity.

- ELT-derived additives improve recovery and reduce creep under load.

- Balanced fiber–rubber ratios maintain mid-temp flexibility of asphalt mastics.

- ELT-derived additives may improve sustainability of pavement materials.

- Improved durability and deformation resistance of asphalt mixtures.

- Possibility for reduction in need for polymer-modified binders and support for circular economy.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Asphalt Mixtures in the Framework of Circular Economy

1.2. New Types of Additives Based on Fibers and Rubber from ELTs

1.3. Scope and Significance of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

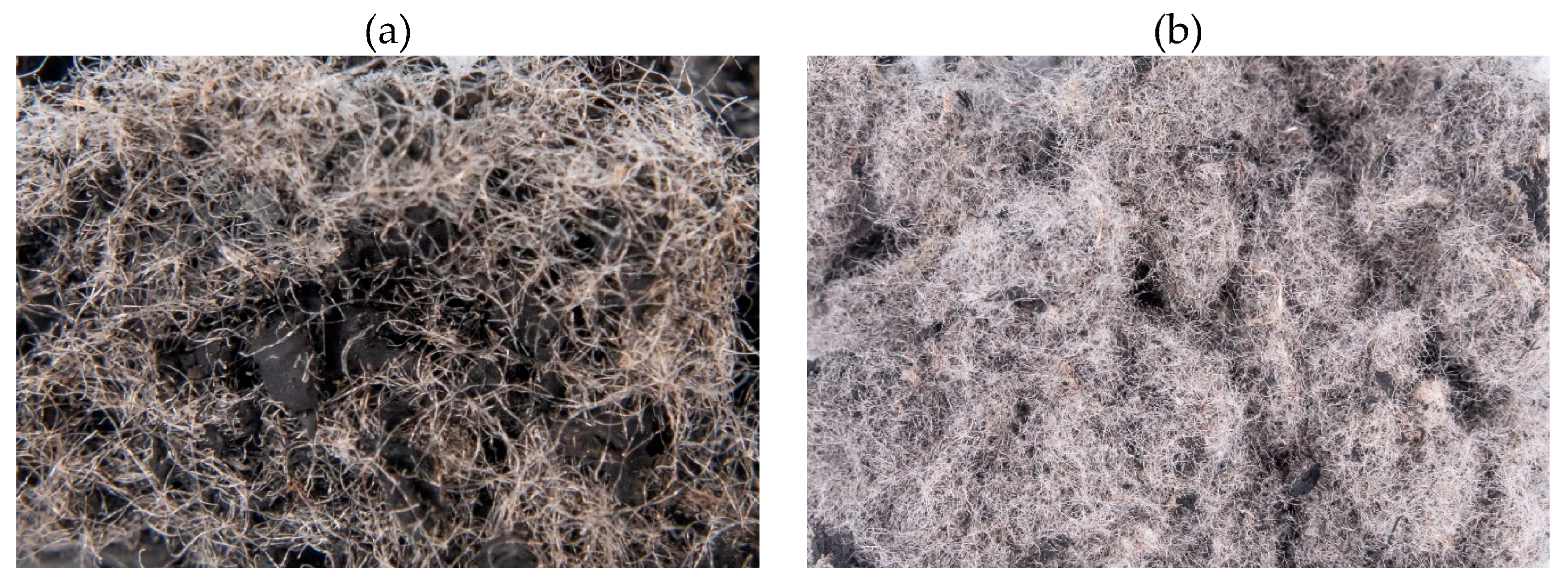

2.1. Materials

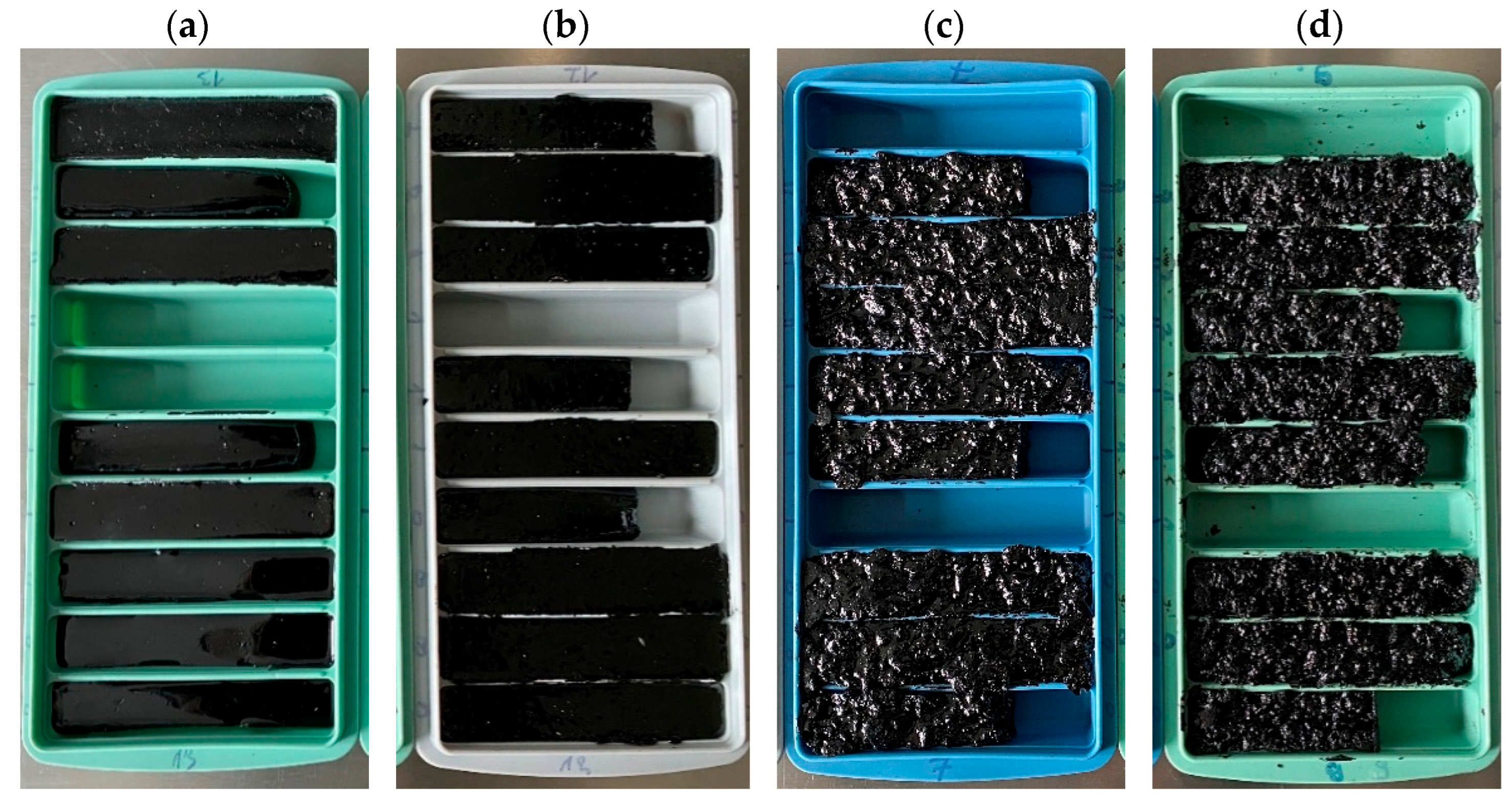

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. Methods

- −

- Dynamic shear modulus (|G*|) and phase angle (δ) determined in accordance with EN 14770 [45], at temperatures from 10 to 90 °C in steps of 10 °C, at frequencies from 0.16 to 16 Hz under controlled strain;

- −

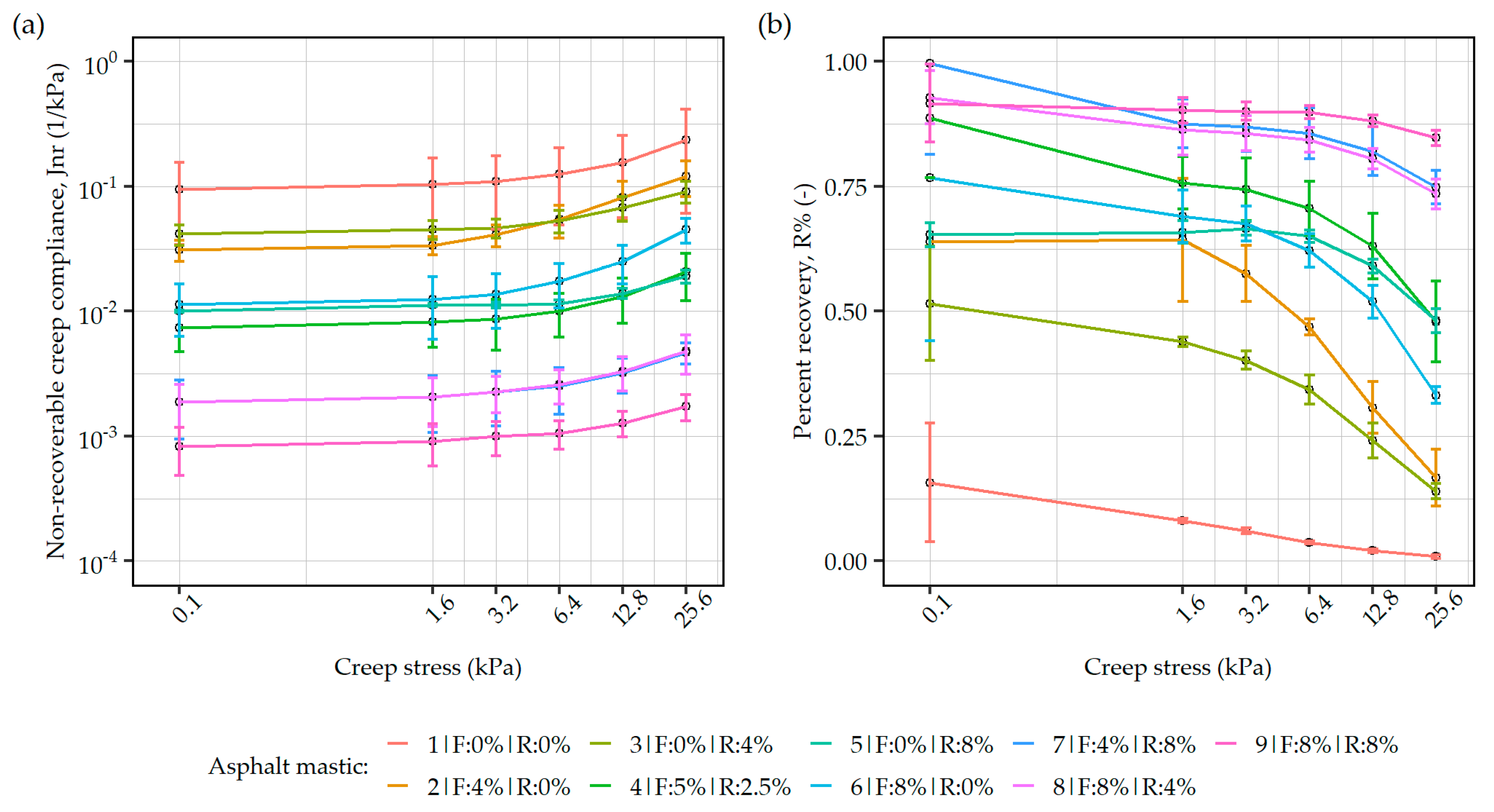

- Multiple stress creep recovery tests carried out in accordance with the EN 16659 [46] at a temperature of 60 °C, in sequences of increasing shear stress values of 0.1, 1.6, 3.2, 6.4, 12.8, and 25.6 kPa.

3. Results

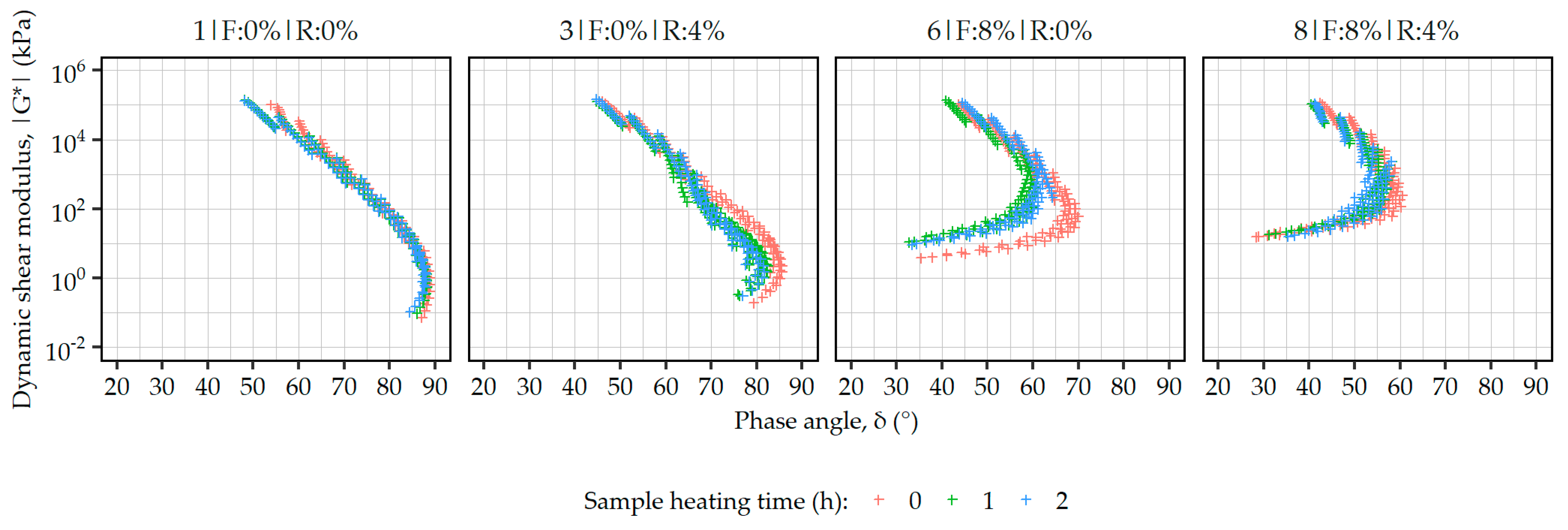

3.1. Temperature Stability of the Asphalt Mastics with ELT-Derived Additives

- −

- 0 h, directly after mixing of the components of the mastics;

- −

- 1 h, corresponding to the transport of asphalt mix;

- −

- 2 h.

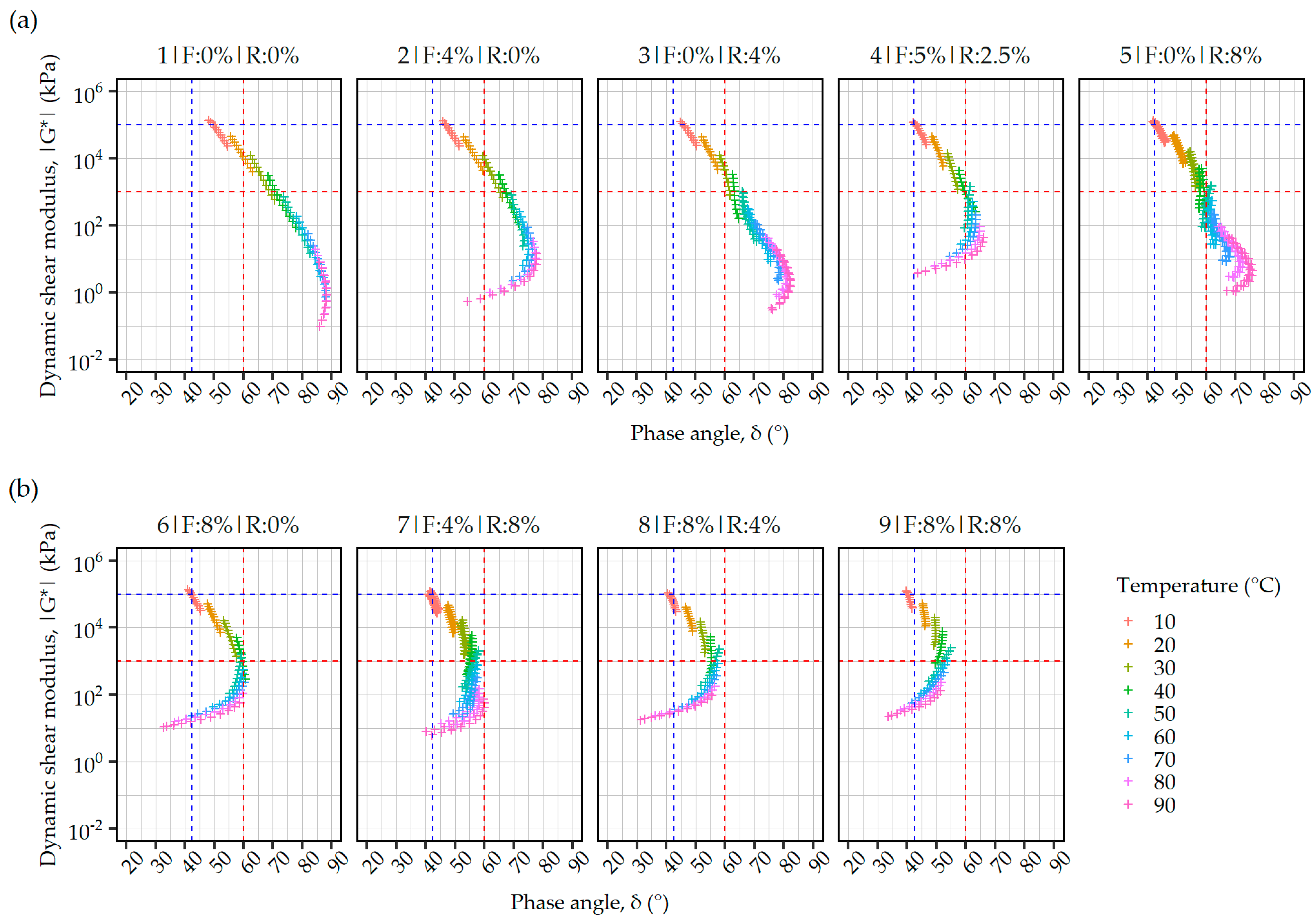

3.2. Effects of the Asphalt Mastics’ Composition with ELT-Derived Additives on Their Rheological Properties

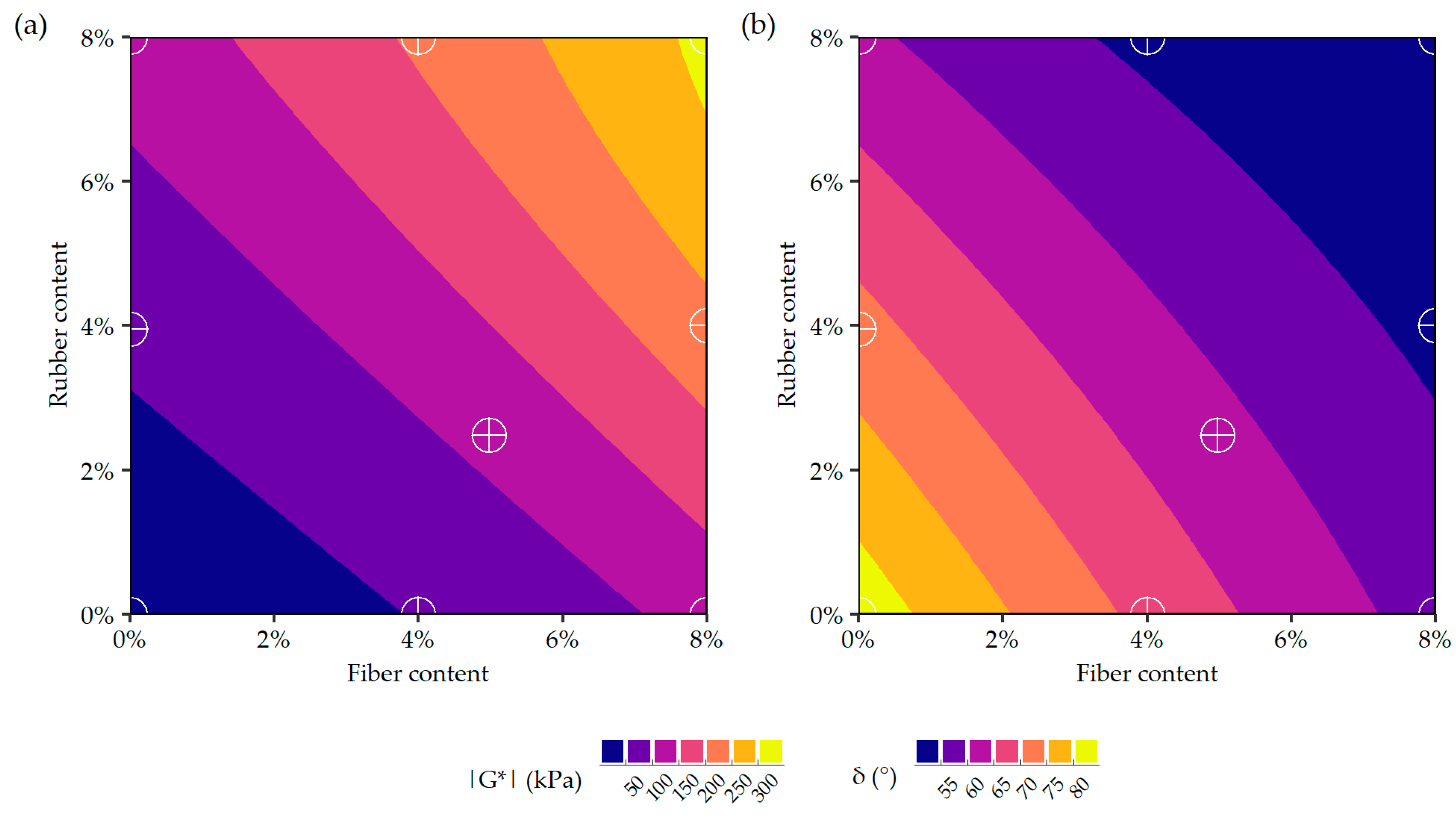

3.2.1. Performance in Oscillatory Tests

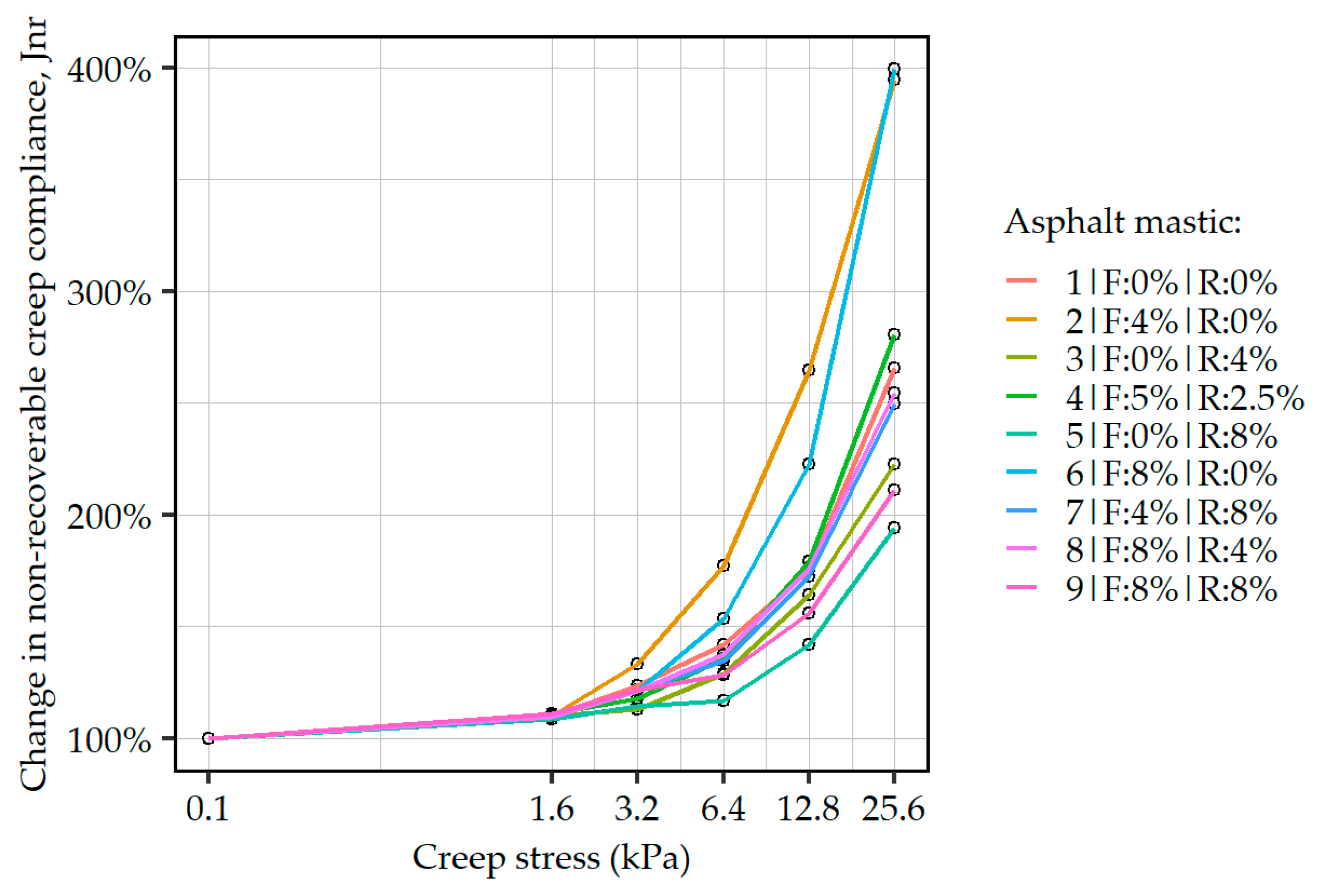

3.2.2. Creep Stress Sensitivity Evaluated in Multiple Stress Creep Recovery Testing

3.2.3. Statistical Modeling of Oscillatory and MSCR Characteristics of Asphalt Mastics with ELT-Derived Additives

4. Discussion

- Introduction of additional solids (fibers), limiting the mobility of the binder;

- Binding of different areas of the asphalt mastic through individual and bundled fibers;

- Adsorption of asphalt binder on the surface of the fibers, reducing the amount of “free” binder;

- Individual fibers may introduce slippage planes under higher stresses.

- The rubber powder acts as an elastic aggregate, also limiting the mobility of the binder and adsorbing some of it;

- Rubber particles, particularly finer ones, may absorb some of the asphalt binder, resulting in swelling and digestion of maltene fractions from the asphalt binder, contributing to the increase in stiffness and elasticity of the asphalt mastic.

5. Conclusions

- The incorporation of synthetic fibers and rubber powder derived from end-of-life tires (ELT) significantly modifies the rheological characteristics of asphalt mastics: improving high-temperature stiffness and elastic recovery while maintaining viable viscoelastic balance in many cases;

- The positive effects on the rheological properties suggest that the use of ELT-derived additives may result in increased resistance to permanent deformation and improved performance (and functional) characteristics;

- While increased additive content enhances elastic response, excessive dosing may reduce low-temperature flexibility and increase brittleness—the DSR testing has shown that a balanced formulation is required to ensure that both high- and intermediate-temperature performance are acceptable; this conclusion can be extrapolated with some caution to low-temperature performance;

- From a sustainability viewpoint, adoption of ELT-derived additives may reduce the need for polymer modifications in bituminous binders, improve durability of asphalt pavements, and support pavement material circularity.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Asphalt Pavement Association. Towards Net Zero—A Decarbonization Roadmap for the Asphalt Industry; European Asphalt Pavement Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shacat, J.; Willis, R.; Ciavola, B. The Carbon Footprint of Asphalt Pavements; National Asphalt Pavement Association (NAPA): Greenbelt, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Constanze, F. The European Green Deal. ESDN Rep. 2020, 9, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Zankavich, V.; Khroustalev, B.; Liu, T.; Veranko, U.; Haritonovs, V.; Busel, A.; Shang, B.; Li, Z. Prospects for Evaluating the Damageability of Asphalt Concrete Pavements during Cold Recycling. Balt. J. Road Bridg. Eng. 2020, 15, 125–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaczewski, M.; Szydłowski, C.; Dołżycki, B. Stiffness of Cold-Recycled Mixtures under Variable Deformation Conditions in the IT-CY Test. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e02066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljković, M.; Poulikakos, L.; Piemontese, F.; Shakoorioskooie, M.; Lura, P. Mechanical Behaviour of Bitumen Emulsion-Cement Composites across the Structural Transition of the Co-Binder System. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 215, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konieczna, K.; Pokorski, P.; Sorociak, W.; Radziszewski, P.; Żymełka, D.; Król, J. Study of the Stiffness of the Bitumen Emulsion Based Cold Recycling Mixes for Road Base Courses. Materials 2020, 13, 5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Yan, X.; Pu, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Fang, K.; Hu, J.; Yang, Y. Quantitative Evaluation on the Energy Saving and Emission Reduction Characteristics of Warm Mix Asphalt Mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 407, 133465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Nguyen, L.N.; Sturlini, E.; Kim, Y.I. Cool Mix Asphalt—Redefining Warm Mix Asphalt with Implementations in Korea, Italy and Vietnam. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, S.; Pacholak, R.; Kołodziej, K.; Woszuk, A. Application of NaP1 Zeolite Modified with Silanes in Bitumen Foaming Process. Materials 2024, 17, 5902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejewski, K.; Chomicz-Kowalska, A.; Remisova, E. Effects of Water-Foaming and Liquid Warm Mix Additive on the Properties and Chemical Composition of Asphalt Binders in Terms of Short Term Ageing Process. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 341, 127756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomicz-Kowalska, A.; Maciejewski, K.; Iwański, M.M. Study of the Simultaneous Utilization of Mechanical Water Foaming and Zeolites and Their Effects on the Properties of Warm Mix Asphalt Concrete. Materials 2020, 13, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaczewski, M.; Szydlowski, C.; Dolzycki, B. Preliminary Study of Linear Viscoelasticity Limits of Cold Recycled Mixtures Determined in Simple Performance Tester (SPT). Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 357, 129432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueche, N.; Probst, S.; Eskandarsefat, S. Warm-Mix Asphalt Containing Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement: A Case Study in Switzerland. Infrastructures 2024, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Fang, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, X. A Comprehensive Review of Bio-Oil, Bio-Binder and Bio-Asphalt Materials: Their Source, Composition, Preparation and Performance. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2022, 9, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwański, M.; Chomicz-Kowalska, A.; Maciejewski, K.; Iwański, M.M.; Radziszewski, P.; Liphardt, A.; Król, J.B.; Sarnowski, M.; Kowalski, K.J.; Pokorski, P. Warm Mix Asphalt Binder Utilizing Water Foaming and Fluxing Using Bio-Derived Agent. Materials 2022, 15, 8873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zborowski, A.; Otkałło, K. Application of Dynamic Complex Stiffness Modulus Master Curves of HMA with Recycled Materials in the Mechanistic-Empirical Design of Road Pavement Structures. Roads Bridg.-Drog. Most. 2023, 22, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pełczyńska, K.; Grajewska, A.; Kopytko, S. Perpetual Pavement Utilizing Crumb Rubber Modified Bitumen: A Case Study of the Trial Section on the S-19 Expressway. Roads Bridg.-Drog. Most. 2023, 22, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Tyre and Rubber Manufacturers’ Association. In Europe 95% of All End of Life Tyres Were Collected and Treated in 2019 (Press Release). Brussels, 11 May 2021. Available online: https://www.etrma.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/20210520_ETRMA_PRESS-RELEASE_ELT-2019.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Radziszewski, P.; Sarnowski, M.; Pokorski, P. Lepiszcza Asfaltowe Modyfikowane Dodatkiem Miału Gumowego Ze Zużytych Opon Samochodowych–Badania i Praktyka. Roads Bridg.-Drog. Most. 2023, 22, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picado-Santos, L.G.; Capitão, S.D.; Dias, J.L.F. Crumb Rubber Asphalt Mixtures by Dry Process: Assessment after Eight Years of Use on a Low/Medium Trafficked Pavement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 215, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, J.; Silva, H.M.R.D.; Hilliou, L.; MacHado, A.V.; Pais, J.; Christopher Williams, R. Mutual Changes in Bitumen and Rubber Related to the Production of Asphalt Rubber Binders. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 36, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zborowski, A.; Ruttmar, I.; Pełczyńska, K.; Grajewska, A.; Kopytko, S. Long-Life Pavement with Rubber-Modified Asphalt Binder: A Case Study of the Test Section on the S-19 Expressway. In Proceedings of the Rubberized Asphalt & Asphalt Rubber 2025 Conference, Lisbon, Portugal, 14–16 October 2025; Sousa, J.B., Way, G., Eds.; LNEC: Lisbon, Portugal, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Pais, J.; Ribeiro, B.; Fagnano, M.; Benedetto, A. How Does Reacted and Activated Rubber Modify the Bitumen and the Mastic. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Maintenance and Rehabilitation of Pavement, Guimarães, Portugal, 24–26 July 2024; Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, 522 LNCE; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedarisetty, S.; Tech, M.; Saha, G.; Sousa, J.B. Performance Characterization of Reacted and Activated Rubber (RAR) Modified Dense Graded Asphalt Mixtures. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Board 96th Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 8–12 January 2017; Volume 3, p. 792. [Google Scholar]

- Landi, D.; Marconi, M.; Meo, I.; Germani, M. Reuse Scenarios of Tires Textile Fibers: An Environmental Evaluation. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 21, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, I.; Panepinto, D.; Zanetti, M. End-of-life Tyres: Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Treatment Scenarios. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, D.; Marconi, M.; Bocci, E.; Germani, M. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Standard, Cellulose-Reinforced and End of Life Tires Fiber-Reinforced Hot Mix Asphalt Mixtures. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 248, 119295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.; Bhasin, A.; Button, J.W. Fibers from Recycled Tire as Reinforcement in Hot Mix Asphalt; National Technical Information Service: Springfield, VA, USA, 2006; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Putman, B.J.; Amirkhanian, S.N. Utilization of Waste Fibers in Stone Matrix Asphalt Mixtures. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2004, 42, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, J.C.; Ferreira, A.; Santos, C.; Pereira, P.; Presti, D. Lo Preliminary Studies to Use Textile Fibers Obtained from Recycled Tires to Reinforce Asphalt Mixtures. Rom. J. Transp. Infrastruct. 2018, 7, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabi-Floody, A.; Mignolet-Garrido, C.; Valdes-Vidal, G. Study of the Effect of the Use of Asphalt Binders Modified with Polymer Fibres from End-of-Life Tyres (ELT) on the Mechanical Properties of Hot Mix Asphalt at Different Operating Temperatures. Materials 2022, 15, 7578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocci, E.; Prosperi, E. Recycling of Reclaimed Fibers from End-of-Life Tires in Hot Mix Asphalt. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2020, 7, 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdes-Vidal, G.; Calabi-Floody, A.; Mignolet-Garrido, C.; Bravo-Espinoza, C. Enhancing Fatigue Resistance in Asphalt Mixtures with a Novel Additive Derived from Recycled Polymeric Fibers from End-of-Life Tyres (ELTs). Polymers 2024, 16, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabi-Floody, A.; Mignolet-Garrido, C.; Valdés-Vidal, G. Evaluation of the Effects of Textile Fibre Derived from End-of-Life Tyres (TFELT) on the Rheological Behaviour of Asphalt Binders. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 360, 129583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sybilski, D. Zastosowanie Odpadów Gumowych w Budownictwie Drogowym. Przegląd Bud. 2009, 80, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Jurczak, R. Pavement with the Addition of Crumb Rubber (and Fibers) after 18 Years of Operation. Drogownictwo 2022, 2–3, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Chomicz-Kowalska, A. Laboratory Testing of Low Temperature Asphalt Concrete Produced in Foamed Bitumen Technology with Fiber Reinforcement. Bull. Polish Acad. Sci. Tech. Sci. 2017, 65, 779–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziej, K.; Bichajło, L.; Siwowski, T. Influence of Composition and Properties of Mastic with Natural Asphalt on Mastic Asphalt Mixture Resistance to Permanent Deformation. Roads Bridg.-Drog. Most. 2021, 20, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Wu, S.; Chen, M.; Zhao, M.; Shu, B. Characteristics of Different Types of Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag Filler and Its Influence on Properties of Asphalt Mastic. Materials 2019, 12, 4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Wu, C. Effects of Type and Content of Mineral Filler on Viscosity of Asphalt Mastic and Mixing and Compaction Temperatures of Asphalt Mixture. Transp. Res. Rec. 2008, 2051, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryś, D.; Jaskuła, P.; Szydłowski, C. Comprehensive Temperature Performance Evaluation of Asphalt Mastics Containing Hydrated Lime Filler Based on Dynamic Shear Rheometer Testing. Roads Bridg.-Drog. Most. 2024, 23, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generalna Dyrekcja Dróg Krajowych i Autostrad. Nawierzchnie Asfaltowe na Drogach Krajowych: WT-2 2014—Część I. Mieszanki Mineralno-Asfaltowe—Wymagania Techniczne; Generalna Dyrekcja Dróg Krajowych i Autostrad: Warsaw, Poland, 2014. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/attachment/34584de6-9577-4d36-876a-2e11c703128c (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- EN 12697-18; Bituminous Mixtures. Test Methods for Hot Mix Asphalt—Binder drainage. Comité Européen de Normalisation (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- EN 14770; Bitumen and Bituminous Binders. Determination of Complex Shear Modulus and Phase Angle—Dynamic Shear Rheometer (DSR). Comité Européen de Normalisation (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2024.

- EN 16659; Bitumen and Bituminous Binders. Multiple Stress Creep and Recovery Test (MSCRT). Comité Européen de Normalisation (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- Zhu, J.; Lundberg, J.; He, L.; Li, G. Extending the Black Diagram of Bitumen to Three Dimensions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 349, 128727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airey, G.P. Use of Black Diagrams to Identify Inconsistencies in Rheological Data. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2002, 3, 403–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzhov, T.; Mullen, K.; Spiess, A.; Bolker, B. R Interface to the Levenberg-Marquardt Nonlinear Least-Squares Algorithm Found in MINPACK, Plus Support for Bounds, version 1.2-4; R Foundation: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, T.S. Systems for Tire Cord-Rubber Adhesion. Rubber Chem. Technol. 1985, 58, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehlivan, M.; Atalik, B.; Gokcesular, S.; Ozbek, S.; Ozbek, B. Optimization of Adhesion in Textile Cord–Rubber Composites: An Experimental and Predictive Modeling Approach. Polymers 2025, 17, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wennekes, W.B.; Noordermeer, J.W.M.; Datta, R.N. Mechanistic Investigations into the Adhesion between RFL-Treated Cords and Rubber. Part I: The Influence of Rubber Curatives. Rubber Chem. Technol. 2007, 80, 545–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Synthetic Fiber (F) | Rubber Powder (R) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material Composition | Average Fiber Length (mm) | Maximum Fiber Length (mm) | Rubber Powder Content (% Fiber Mass) | Source | Particle Size (mm) | Fiber Content (% of Rubber Powder Mass) |

| polyesters poliamides aramides viscose | 2.9 | 13 | 24% | passenger car tires | 0/0.8 | 15% |

| Asphalt Mastic | Sample Heating Time (h) | |G*| (kPa) | δ (°) | Jnr (1/kPa) | R% (-) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 °C | 60 °C | 80 °C | 20 °C | 60 °C | 80 °C | 3.2 kPa | 25.6 kPa | 3.2 kPa | 25.6 kPa | ||

| 1|F:0%|R:0% | 0 | 11,771 | 20.2 | 1.78 | 61.8 | 83.5 | 87.9 | 0.211 | 480.31 | 0.039 | 0.005 |

| 1 | 15,047 | 24.9 | 2.16 | 59.0 | 82.8 | 87.7 | 0.110 | 236.95 | 0.060 | 0.009 | |

| 2 | 15,119 | 26.3 | 2.27 | 58.9 | 82.8 | 87.5 | 0.129 | 297.93 | 0.053 | 0.007 | |

| 3|F:0%|R:4% | 0 | 14,644 | 40.7 | 3.86 | 56.0 | 78.4 | 84.9 | 0.074 | 0.136 | 0.253 | 0.060 |

| 1 | 15,469 | 56.6 | 6.09 | 54.9 | 71.3 | 80.2 | 0.046 | 0.091 | 0.402 | 0.139 | |

| 2 | 18,064 | 53.2 | 5.92 | 54.7 | 71.0 | 79.2 | 0.040 | 0.089 | 0.475 | 0.178 | |

| 6|F:8%|R:0% | 0 | 14,104 | 70.2 | 12.40 | 52.6 | 68.0 | 60.7 | 0.023 | 0.066 | 0.606 | 0.244 |

| 1 | 18,061 | 126.4 | 29.10 | 48.8 | 57.5 | 48.3 | 0.013 | 0.045 | 0.676 | 0.332 | |

| 2 | 16,167 | 119.9 | 27.03 | 53.3 | 59.0 | 51.4 | 0.008 | 0.022 | 0.759 | 0.486 | |

| 8|F:8%|R:4% | 0 | 16,836 | 134.2 | 33.16 | 49.4 | 58.3 | 47.2 | 0.007 | 0.019 | 0.755 | 0.455 |

| 1 | 19,382 | 228.5 | 51.69 | 48.1 | 54.5 | 49.2 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.856 | 0.734 | |

| 2 | 19,188 | 252.4 | 56.39 | 47.7 | 53.7 | 49.4 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.884 | 0.790 | |

| Asphalt Mastic | ν | α | β | γ | C1 | C2 | Lower Modulus Asymptote (kPa) | Upper Modulus Asymptote (kPa) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1|F:0%|R:0% | −4.600 | 10.583 | −0.456 | −0.360 | 9.94 | 132.74 | 2.51 × 10−5 | 9.61 × 105 | 0.9989 |

| 2|F:4%|R:0% | −2.505 | 8.344 | −0.171 | −0.388 | 10.03 | 132.50 | 3.12 × 10−3 | 6.90 × 105 | 0.9986 |

| 3|F:0%|R:4% | −5.881 | 12.046 | −0.693 | −0.288 | 9.75 | 127.21 | 1.31 × 10−6 | 1.46 × 106 | 0.9993 |

| 4|F:5%|R:2.5% | −1.064 | 6.885 | −0.014 | −0.371 | 11.33 | 143.07 | 8.64 × 10−2 | 6.63 × 105 | 0.9992 |

| 5|F:0%|R:8% | −4.777 | 10.826 | −0.703 | −0.277 | 10.35 | 128.31 | 1.67 × 10−5 | 1.12 × 106 | 0.9972 |

| 6|F:8%|R:0% | 0.608 | 4.788 | 0.531 | −0.496 | 14.77 | 172.47 | 4.06 × 100 | 2.49 × 105 | 0.9962 |

| 7|F:4%|R:8% | −1.563 | 7.379 | −0.271 | −0.309 | 10.59 | 129.29 | 2.73 × 10−2 | 6.53 × 105 | 0.9852 |

| 8|F:8%|R:4% | 0.151 | 5.472 | 0.167 | −0.382 | 11.65 | 140.60 | 1.42 × 100 | 4.20 × 105 | 0.9991 |

| 9|F:8%|R:8% | 0.227 | 5.450 | 0.088 | −0.355 | 13.75 | 152.22 | 1.68 × 100 | 4.75 × 105 | 0.9992 |

| Dependent Variable: log10(|G*|) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 10 °C | 20 °C | 30 °C | 40 °C | 50 °C | 60 °C | 70 °C | 80 °C | 90 °C |

| Intercept | 4.771 *** | 4.160 *** | 3.444 *** | 2.720 *** | 1.953 *** | 1.313 *** | 0.743 *** | 0.26 ** | −0.148 |

| F | −0.208 | 0.979 | 2.597 ** | 4.364 *** | 7.808 *** | 10.754 *** | 14.435 *** | 18.016 *** | 21.834 *** |

| R | 0.134 | 1.277 | 2.917 *** | 4.658 *** | 11.794 *** | 14.064 *** | 15.285 *** | 15.582 *** | 15.413 *** |

| F2 | - | - | - | - | −8.175 | −15.492 | −28.569 | −41.014 | −56.902 |

| R2 | - | - | - | - | −50.824 * | −54.127 ** | −48.827 * | −42.475 | −37.881 |

| F:R | 7.802 | 2.816 | −1.032 | −6.222 | −37.898 ** | −56.163 *** | −73.214 *** | −84.513 *** | −92.866 ** |

| Adj. R2 | 0.143 | 0.528 | 0.824 | 0.901 | 0.952 | 0.968 | 0.969 | 0.956 | 0.935 |

| Dependent Variable: δ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 10 °C | 20 °C | 30 °C | 40 °C | 50 °C | 60 °C | 70 °C | 80 °C | 90 °C |

| Intercept | 51.438 *** | 59.005 *** | 65.934 *** | 71.757 *** | 78.013 *** | 82.943 *** | 84.424 *** | 84.889 *** | 87.477 *** |

| F | −88.614 ** | −102.962 ** | −121.065 ** | −142.53 * | −278.16 *** | −399.782 *** | −388.364 *** | −473.11 *** | −942.511 *** |

| R | −71.89 ** | −88.407 * | −130.477 ** | −185.947 ** | −287.503 *** | −291.177 ** | −250.032 *** | −197.04 * | −78.488 |

| F2 | −270.556 | −262.453 | −244.489 | −335.747 | 619.411 | 1130.223 | - | - | 4717.963 * |

| R2 | −237.511 | −209.27 | 17.296 | 214.896 | 711.319 | 231.33 | - | - | −1030.968 |

| F:R | 825.202 *** | 767.903 ** | 784.963 * | 1017.535 * | 1697.747 *** | 2200.029 ** | 2326.76 * | 2356.40 | 2423.363 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.936 | 0.932 | 0.929 | 0.918 | 0.949 | 0.915 | 0.833 | 0.763 | 0.785 |

| Dependent Variable: log10(Jnr) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creep Stress (kPa) | 0.1 | 1.6 | 3.2 | 6.4 | 12.8 | 25.6 |

| Intercept | −0.920 *** | −0.886 *** | −0.853 *** | −0.783 *** | −0.679 *** | −0.518 *** |

| F | −20.729 *** | −20.553 *** | −19.309 *** | −17.759 *** | −15.645 *** | −14.131 *** |

| R | −15.301 *** | −15.120 *** | −16.180 *** | −17.046 *** | −17.654 *** | −18.859 *** |

| F2 | 94.688 * | 93.156 ** | 80.516 * | 65.846 | 48.076 | 41.061 |

| R2 | 27.777 | 25.759 | 35.287 | 38.558 | 44.601 | 57.797 |

| F:R | −24.389 | −24.731 | −22.398 | −26.842 | −37.441 | −50.520 * |

| Adj. R2 | 0.958 | 0.958 | 0.961 | 0.961 | 0.963 | 0.971 |

| Dependent Variable: R% | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creep Stress (kPa) | 0.1 | 1.6 | 3.2 | 6.4 | 12.8 | 25.6 |

| Intercept | 0.156 * | 0.117 *** | 0.079 *** | 0.030 | −0.027 | −0.059. |

| F | 17.268 *** | 15.175 *** | 14.694 *** | 13.620 *** | 11.609 *** | 8.438 *** |

| R | 11.349 ** | 9.403 *** | 9.702 *** | 9.895 *** | 9.319 *** | 7.662 *** |

| F2 | −122.026 ** | −95.276 *** | −85.996 *** | −73.895 *** | −56.578 *** | −40.107 * |

| R2 | −62.166 | −36.582 ** | −33.944 *** | −31.789 *** | −25.436 * | −17.272 |

| F:R | −54.367 * | −56.752 *** | −59.510 *** | −52.774 *** | −33.292 *** | 6.147 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.749 | 0.968 | 0.982 | 0.987 | 0.971 | 0.956 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Maciejewski, K.; Zankowicz, W.; Chomicz-Kowalska, A.; Zaprzalski, P. Effects of Synthetic Fibers and Rubber Powder from ELTs on the Rheology of Mineral Filler–Bitumen Compositions. Materials 2026, 19, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010052

Maciejewski K, Zankowicz W, Chomicz-Kowalska A, Zaprzalski P. Effects of Synthetic Fibers and Rubber Powder from ELTs on the Rheology of Mineral Filler–Bitumen Compositions. Materials. 2026; 19(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaciejewski, Krzysztof, Witalij Zankowicz, Anna Chomicz-Kowalska, and Przemysław Zaprzalski. 2026. "Effects of Synthetic Fibers and Rubber Powder from ELTs on the Rheology of Mineral Filler–Bitumen Compositions" Materials 19, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010052

APA StyleMaciejewski, K., Zankowicz, W., Chomicz-Kowalska, A., & Zaprzalski, P. (2026). Effects of Synthetic Fibers and Rubber Powder from ELTs on the Rheology of Mineral Filler–Bitumen Compositions. Materials, 19(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010052