Degradation Behavior of Surface Wear Resistance of Marine Airport Rigid Pavements

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Cement

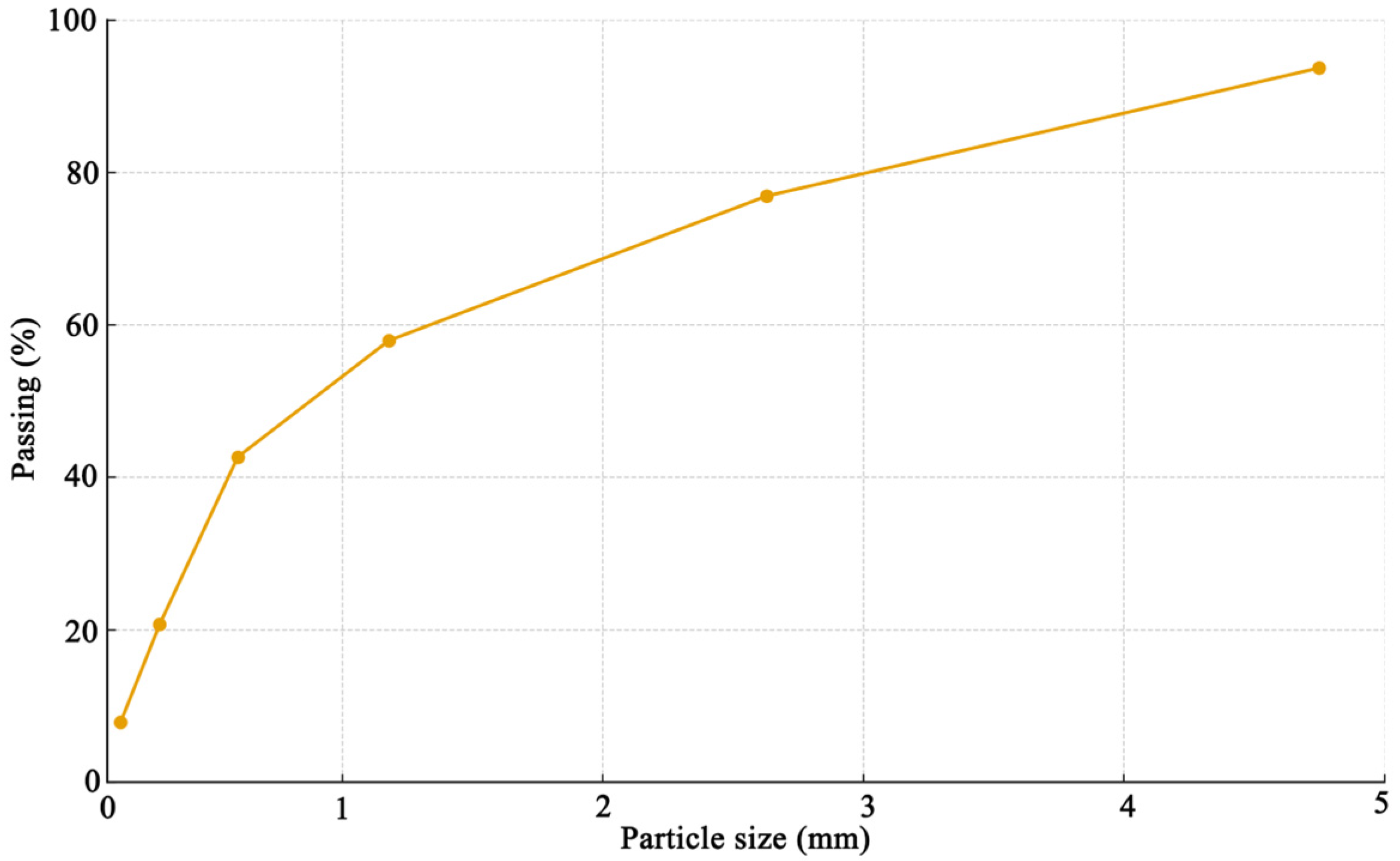

2.1.2. Fine Aggregate

2.1.3. C40 Concrete Specimens

2.2. Experimental Design

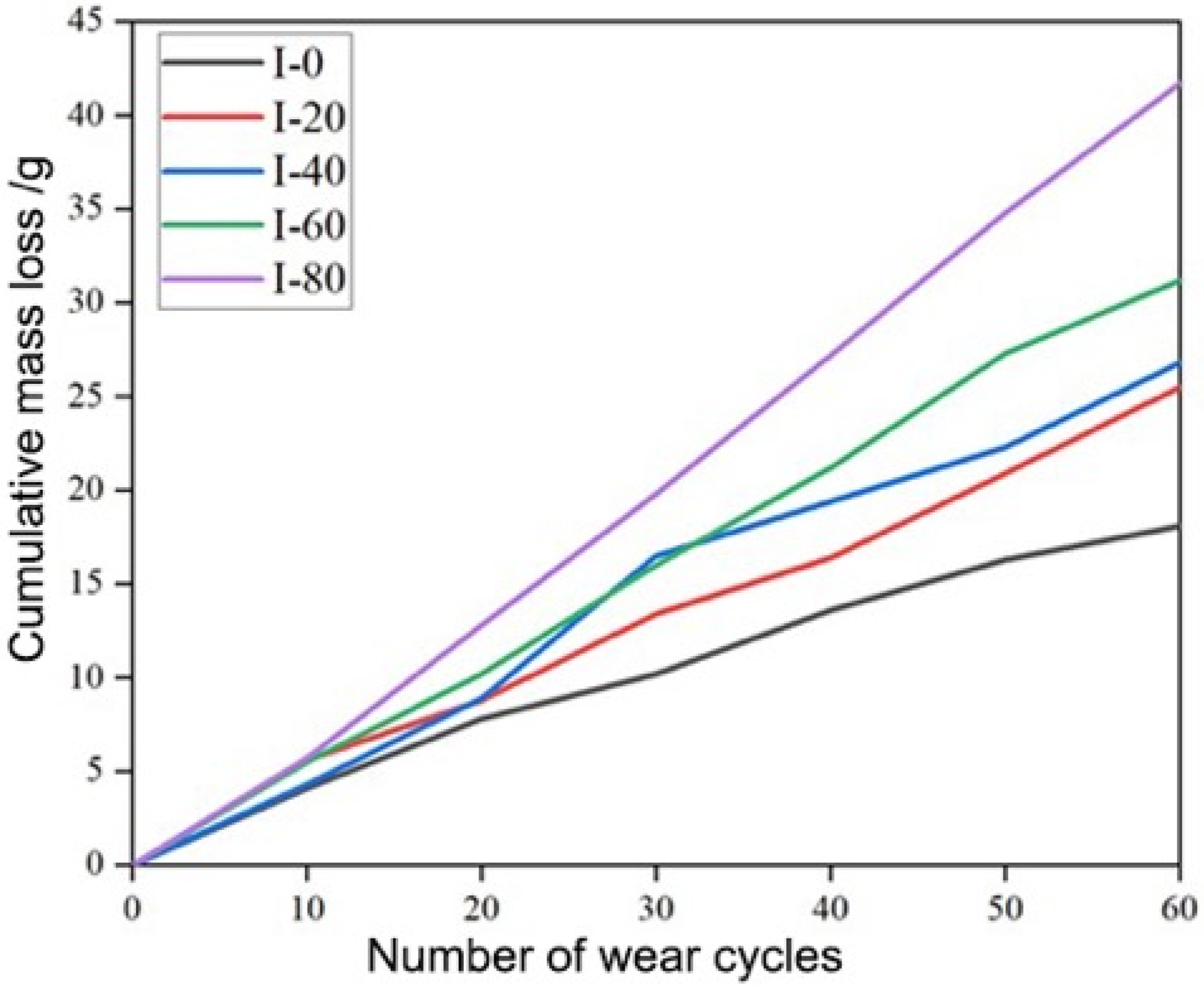

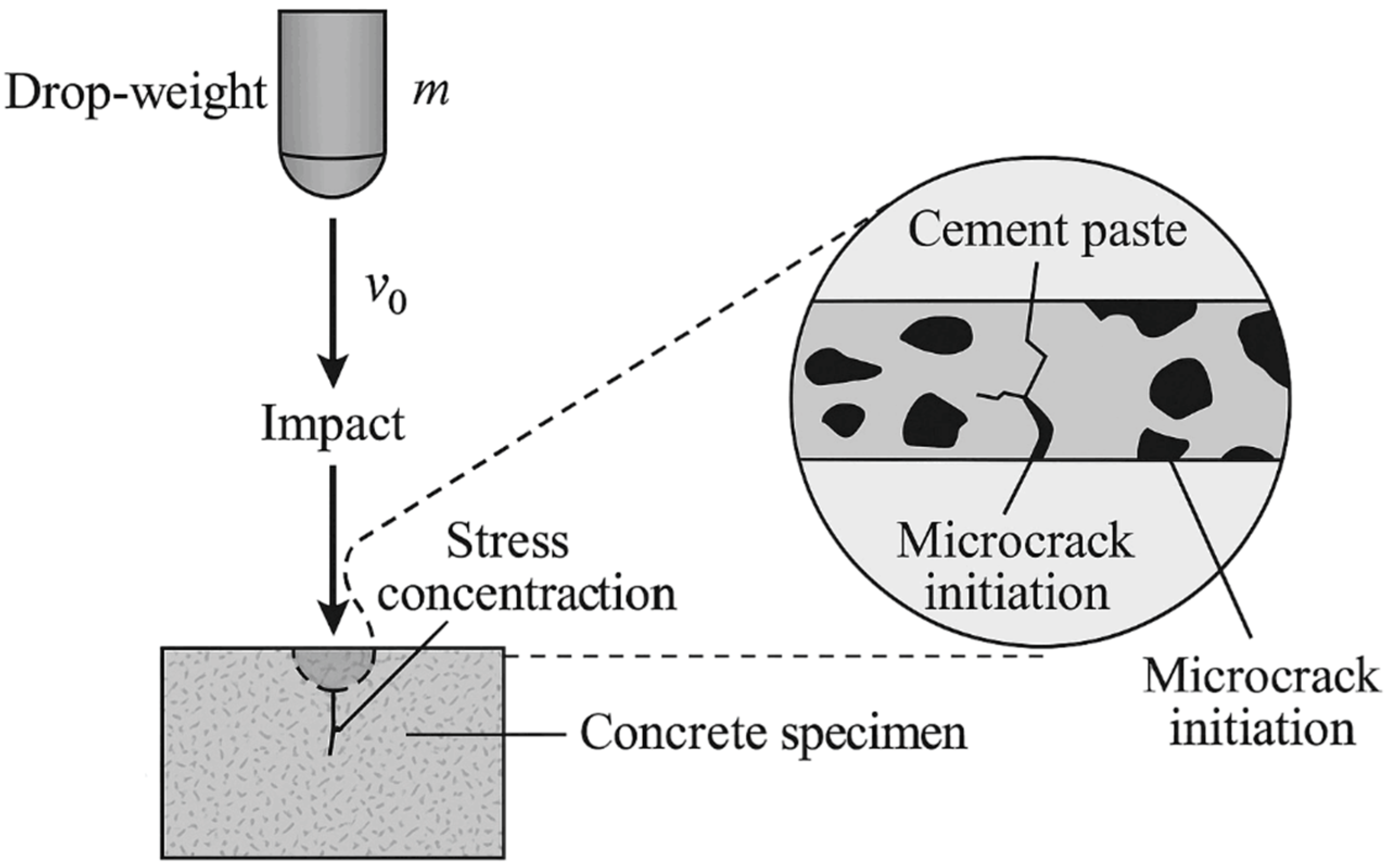

2.2.1. Effect of Mechanical Impact Loading on the Wear Resistance of Concrete

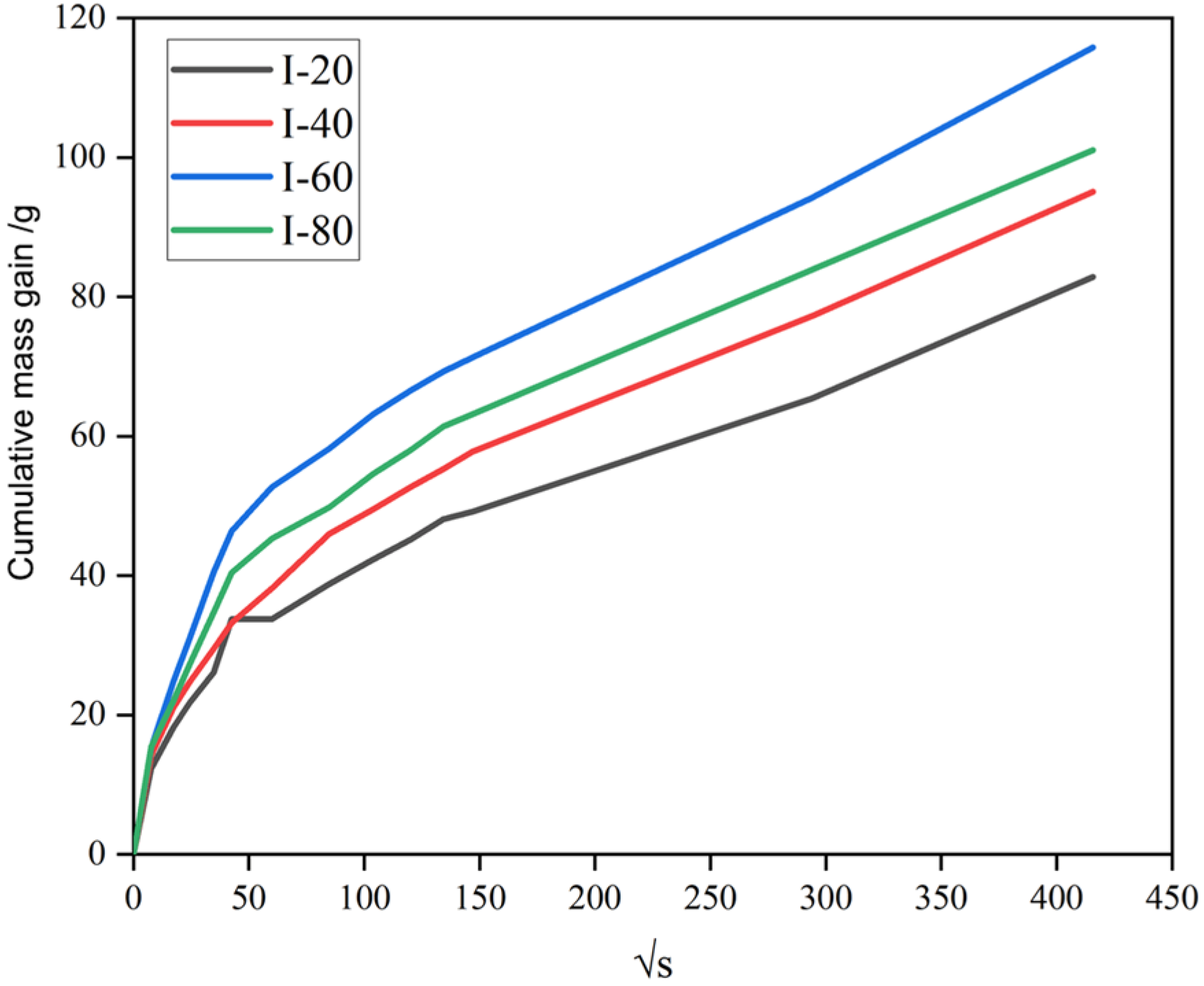

2.2.2. Effect of Salt Fog Corrosion on the Wear Resistance of Concrete

2.2.3. Combined Effect of Drop-Weight Impact and Salt Fog Corrosion on the Wear Resistance of Concrete

3. Results and Discussion

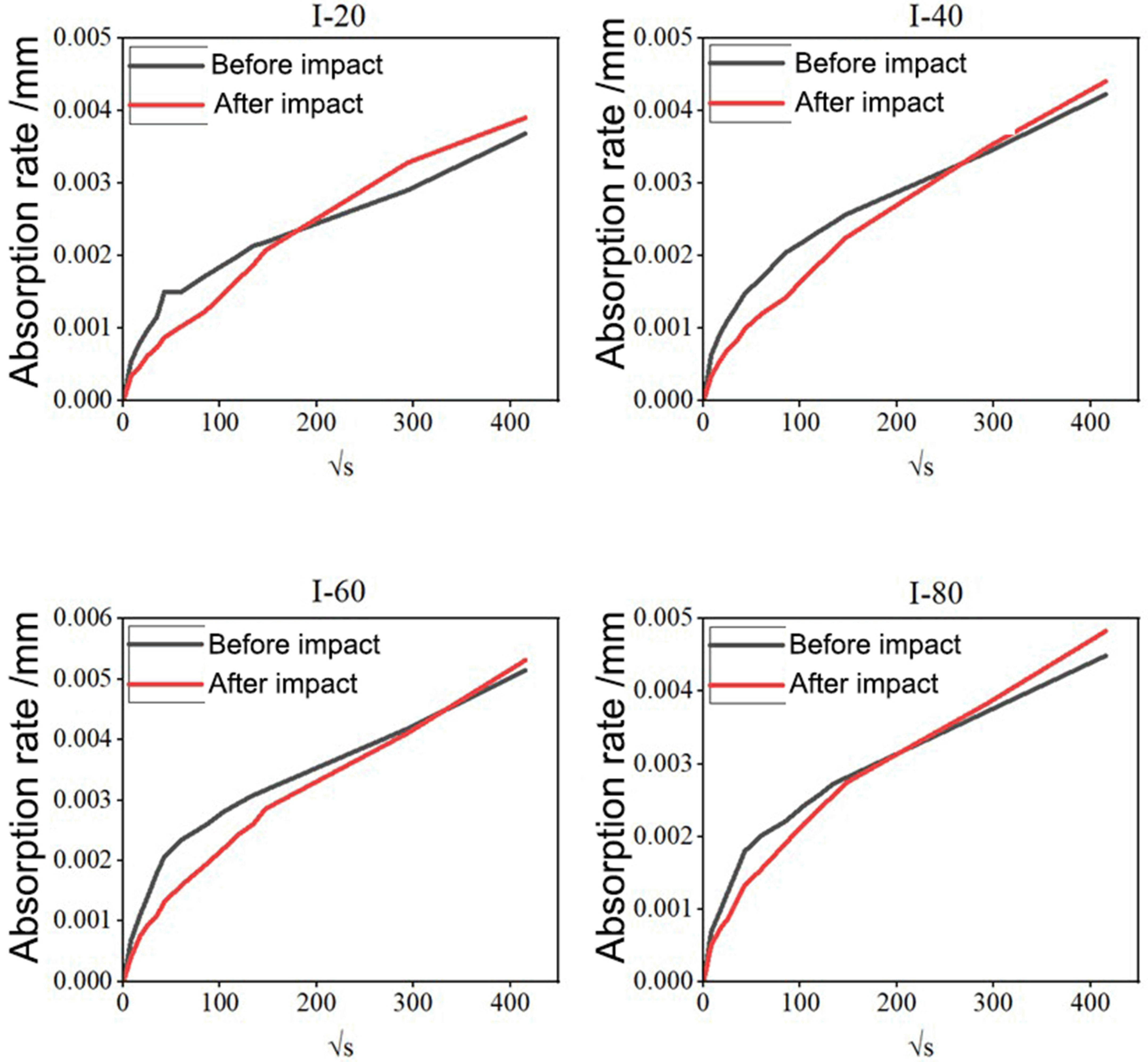

3.1. Effect of Repeated Impact Loading on the Wear Resistance of Concrete

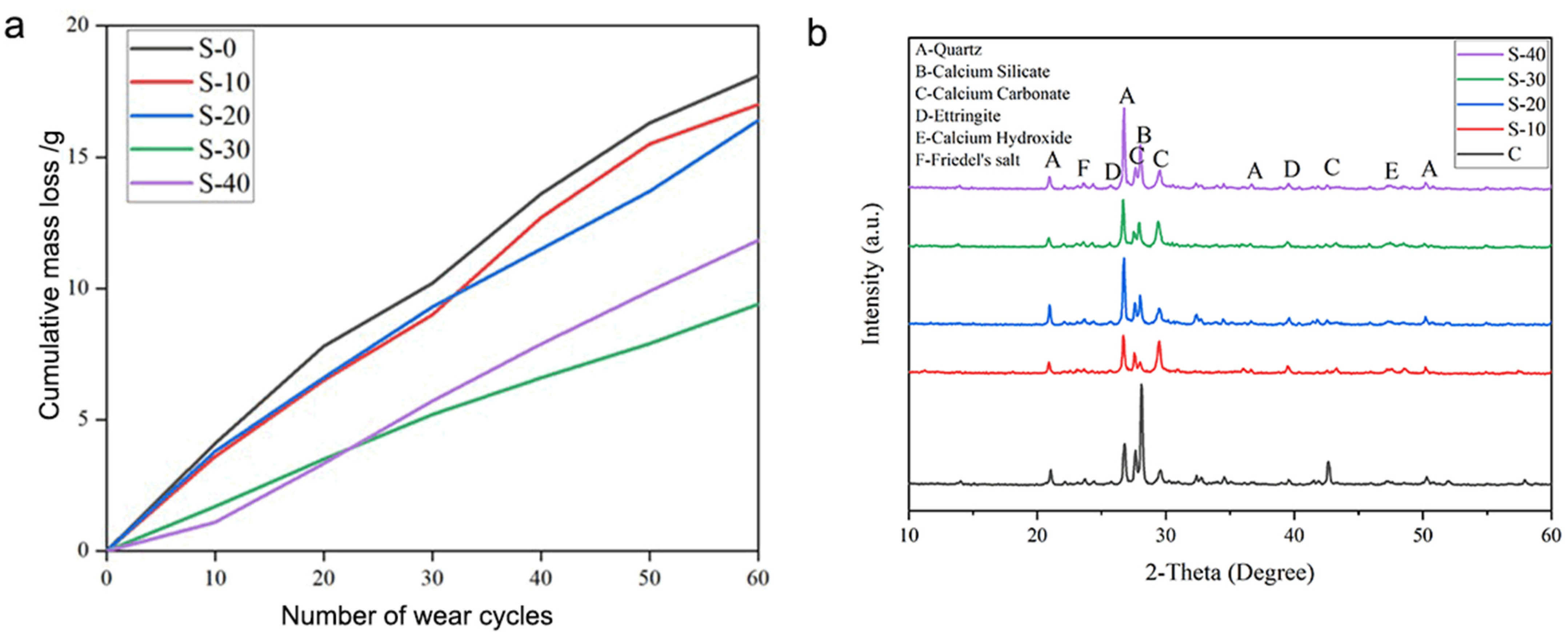

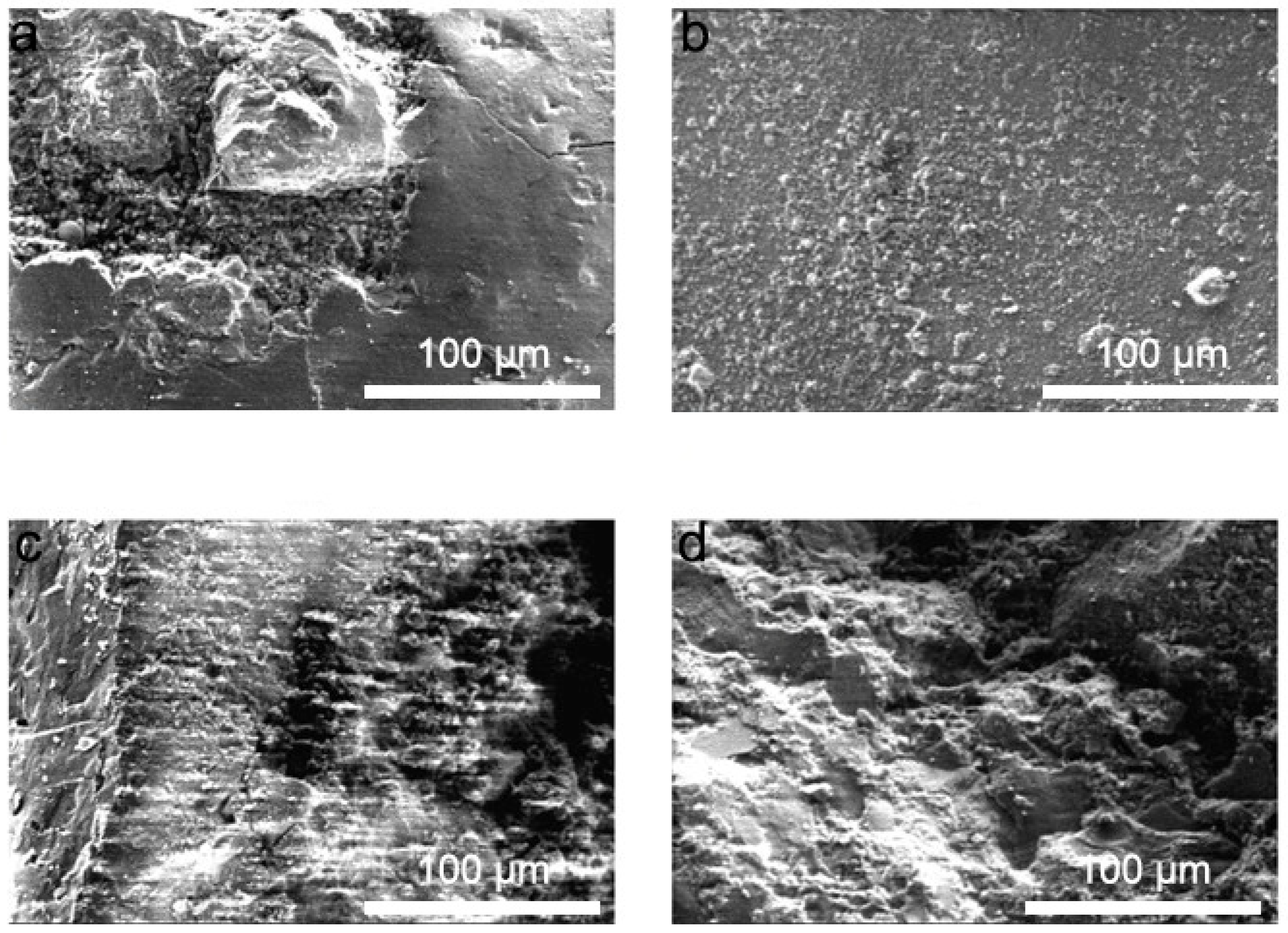

3.2. Effect of Salt-Fog Exposure on the Wear Resistance of Concrete

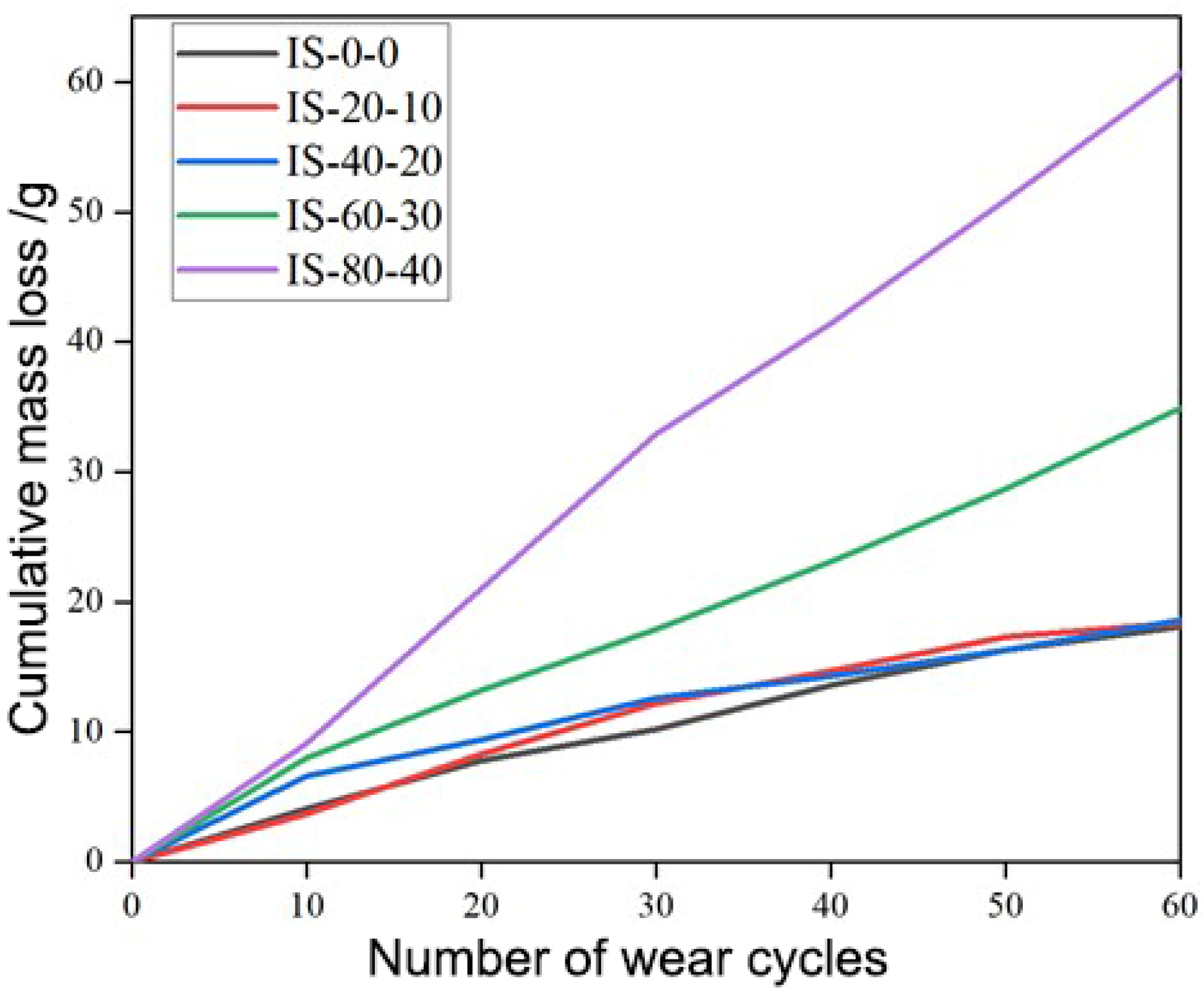

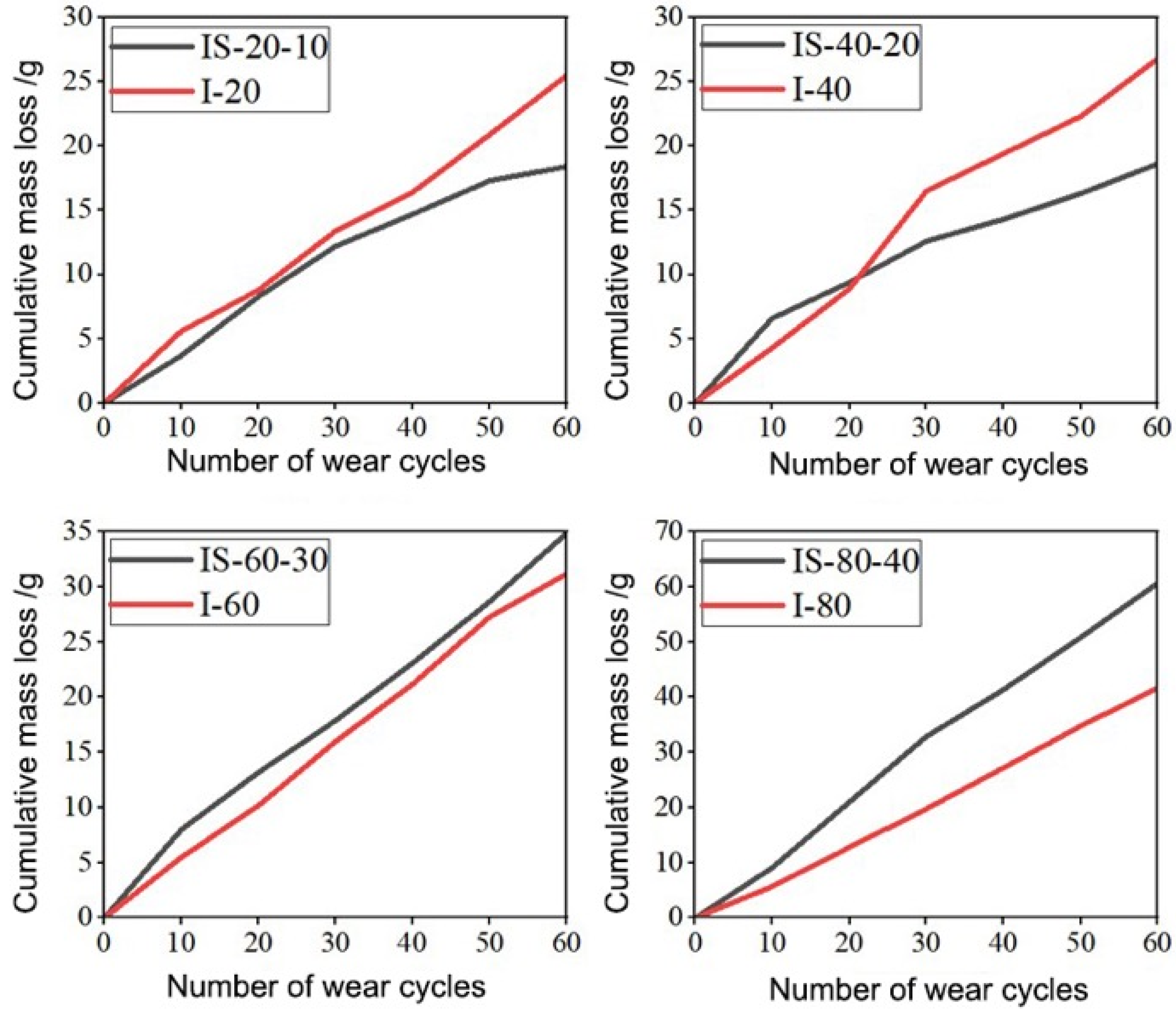

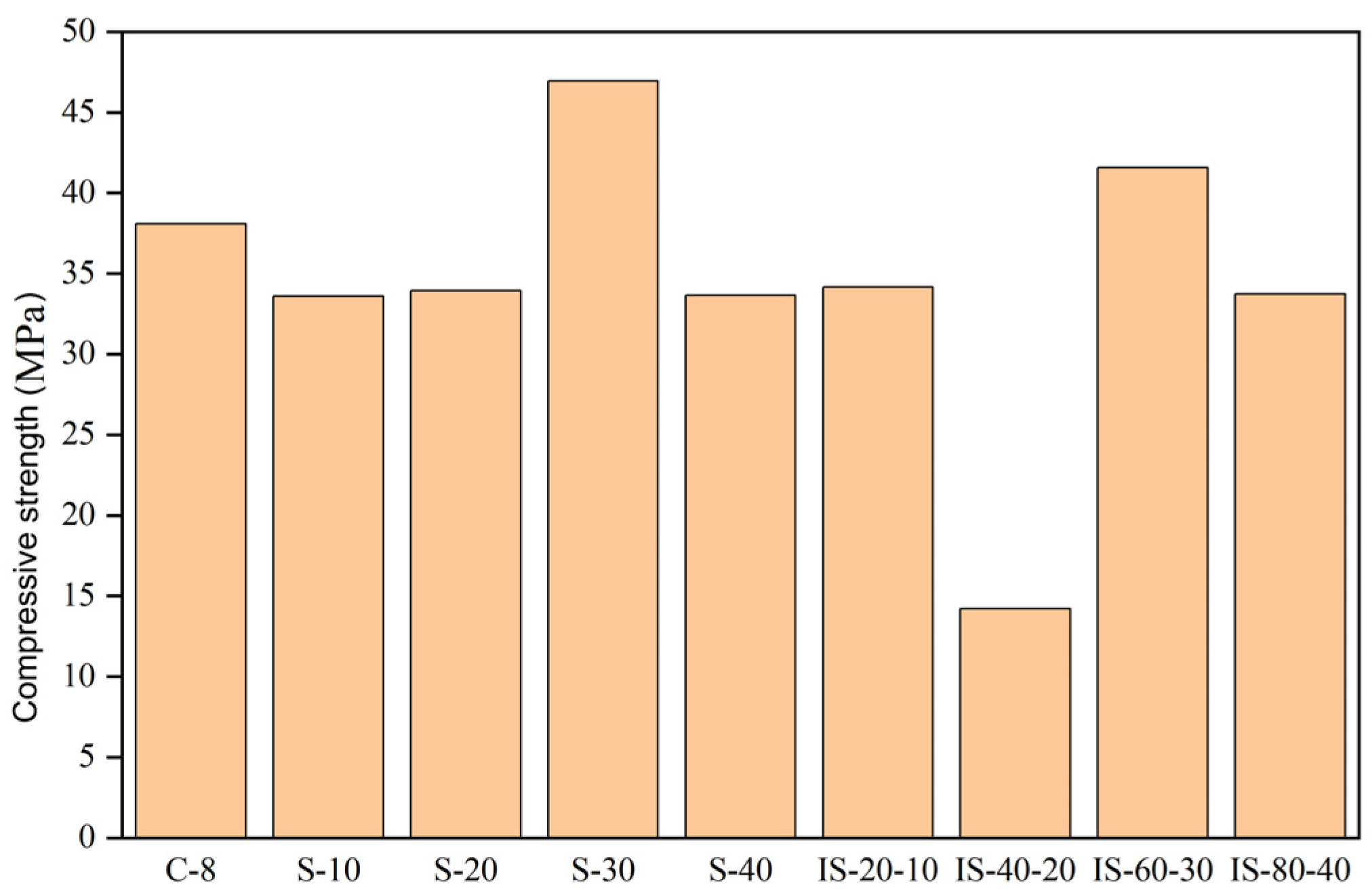

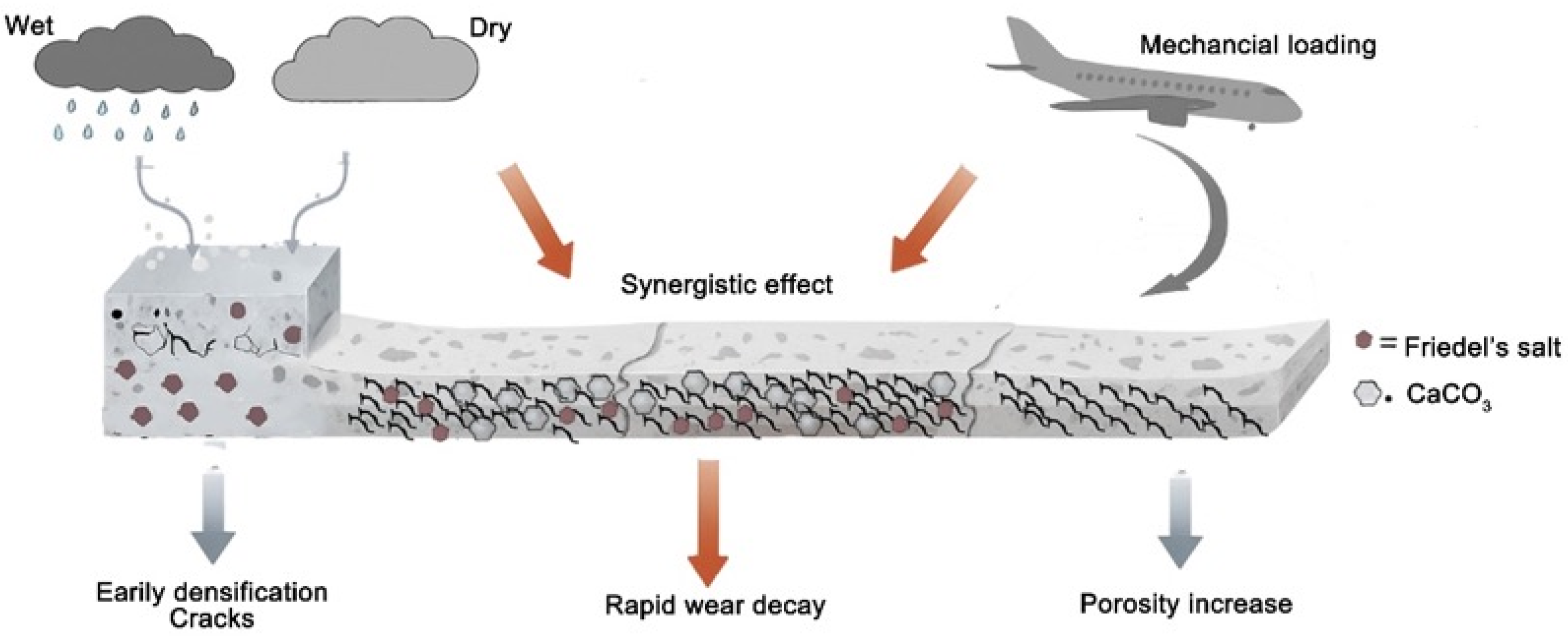

3.3. Effect of Combined Impact Loading and Salt-Fog Cycles on the Wear Resistance of Concrete

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fwa, T.F. Pavement skid resistance properties for safe aircraft operations. J. Road Eng. 2024, 4, 361–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Liu, X.; Thambiratnam, D.P.; Fawzia, S. Enhancing the impact performance of runway pavements with improved composition. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 130, 105739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.B.; Kim, S.-M. In Situ Experimental Analysis and Performance Evaluation of Airport Precast Concrete Pavement System Subjected to Environmental and Moving Airplane Loads. Materials 2024, 17, 5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhang, J. Fatigue Models for Airfield Concrete Pavement: Literature Review and Discussion. Materials 2021, 14, 6519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Weng, X.; Jiang, L.; Yang, B.; Liu, J.; Qu, B. Durability of airport concrete pavement improved by four novel coatings. Adv. Cem. Res. 2019, 31, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Lv, Z.; Cui, J.; Tian, Z.; Li, Z. Durability of Marine Concretes with Nanoparticles under Combined Action of Bending Load and Salt Spray Erosion. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1968770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, W.; Meng, Y.; Li, H. Deterioration of sea sand roller compacted concrete used in island reef airport runway under salt spray. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 322, 126523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, W.; Wang, F.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Meng, Q.; Huo, F.; Zhao, D.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, J. A state-of-the-art assessment in developing advanced concrete materials for airport pavements with improved performance and durability. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Gao, J.; Qi, B.; Shen, D.; Li, L. Degradation progress of concrete subject to combined sulfate-chloride attack under drying-wetting cycles and flexural loading. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 151, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Zhang, M.; Cui, J. A review on the deterioration of mechanical and durability performance of marine-concrete under the scouring action. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 66, 105924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulińska, S.; Sujak, A.; Pyzalski, M. Sustainable management of photovoltaic waste through recycling and material use in the construction industry. Materials 2025, 18, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golewski, P.; Sadowski, T. Technological and Strength Aspects of Layers Made of Different Powders Laminated on a Polymer Matrix Composite Substrate. Molecules 2022, 27, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Zhao, L.; Xia, H.; Li, X.; Cui, L.; Niu, Y. Preparation and properties of octadecylamine modified SiO2/silicon-acrylic coating for concrete anti-snowmelt salt corrosion. Prog. Org. Coat. 2025, 202, 109155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Wang, L.; Wittmann, F.H.; De Belie, N.; Schlangen, E.; Alava, H.E.; Wang, Z.; Kessler, S.; Gehlen, C.; Yunus, B.M. Test methods to determine durability of concrete under combined environmental actions and mechanical load: Final report of RILEM TC 246-TDC. Mater. Struct. 2017, 50, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Miao, Y.; Lantieri, C. Review of research on tire–pavement contact behavior. Coatings 2024, 14, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Shen, A.; Zhou, D.; Zhou, J.; Li, W. Chloride ion penetration and sulfate attack resistance of self-curing concrete cooperatively cured with superabsorbent polymers and waterborne epoxy coatings in composite corrosion environments. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 492, 142974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, W.; Meng, Y. Salt Spray Resistance of Roller-Compacted Concrete with Surface Coatings. Materials 2023, 16, 7134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arowojolu, O.S.; Rangelov, M.; Nassiri, S.; Bayomy, F.; Ibrahim, A. Concrete Durability Performance in Aggressive Salt and Deicing Environments-Case Study of Select Pavement and Bridge Concrete Mixtures. Materials 2025, 18, 1266. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Liu, X.; Wei, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, D. Study on the wear-resistant mechanism of concrete based on wear theory. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 271, 121594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Zhang, M.; Sun, Y. Research on The Chloride Diffusion Modified Model for Marine Concretes with Nanoparticles under The Action of Multiple Environmental Factors. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, H.; Lian, S.; Tang, X. Drying–Wetting Correlation Analysis of Chloride Transport Behavior and Mechanism in Calcium Sulphoaluminate Cement Concrete. Materials 2024, 17, 4600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durczak, K.; Pyzalski, M.; Brylewski, T.; Sujak, A. Effect of variable synthesis conditions on the formation of ye’elimite-aluminate-calcium (YAC) cement and its hydration in the presence of portland cement (OPC) and several accessory additives. Materials 2023, 16, 6052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, A.; Kim, H.; Lee, S.-J.; Lee, M.-S. Assessing Abrasion Resistance in Concrete Pavements: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, W.; Wang, D.; Cheng, H.; Yang, R.; Wang, Y. Joint improvements of skid and abrasion resistance of concrete pavements through manufactured micro-and macro-textures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 487, 142033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C944/C944M; Standard Test Method for Abrasion Resistance of Concrete or Mortar Surfaces by the Rotating-Cutter Method. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- GB/T 16925; Test Method for Abrasion Resistance of Concrete and Its Products (Ball Bearing Method). Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 1997. (In Chinese)

- Chen, S.; Ren, J.; Ren, X.; Li, Y. Deterioration laws of concrete durability under the coupling action of salt erosion and drying–wetting cycles. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 1003945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 175-2007; Common Portland Cements. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2007.

- GB/T 14684-2022; Sand for Construction. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- GB/T 10125; Corrosion Tests in Artificial Atmospheres—Salt Spray Tests. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- ISO 9227; Corrosion Tests in Artificial Atmospheres—Salt Spray Tests. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Tan, B. Experimental Study on Damage Evolution Characteristics of Concrete under Impact Load Based on EMI Method. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, S.; Dawson, A.R.; Thom, N.H. Impact load-induced micro-structural damage and micro-structure associated mechanical response of concrete made with different surface roughness and porosity aggregates. Cem. Concr. Res. 2012, 42, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Andersen, L.V.; Zhang, M.; Wu, M. Abrasion damage of concrete for hydraulic structures and mitigation measures: A comprehensive review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 422, 135754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uliasz-Bocheńczyk, A.; Mokrzycki, E.; Gawlicki, M.; Pyzalski, M. Polymorphic varieties of CaCO3 as a product of cement grout carbonization. Gospod. Surowcami Miner.-Miner. Resour. Manag. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Shi, Z.; Shi, C.; Ling, T.-C.; Li, N. A review on surface treatment for concrete–Part 2: Performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 133, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Shi, Z.; Shi, C.; Ling, T.-C.; Li, N. A review on concrete surface treatment Part I: Types and mechanisms. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 132, 578–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, G.; Liu, P.; Guo, X.; Xu, J. Concrete Durability after Load Damage and Salt Freeze–Thaw Cycles. Materials 2022, 15, 4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guo, H.; Zhang, Y. Deterioration of concrete under the coupling action of freeze–thaw cycles and salt solution erosion. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2022, 61, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Kang, A.; Xiao, P.; Kou, C.; Gong, Y.; Xiao, C. Influences of spraying sodium silicate based solution/slurry on recycled coarse aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 377, 130924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, R.; Liu, K.; Sun, S. Research progress on durability of marine concrete under the combined action of Cl− erosion, carbonation, and dry–wet cycles. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2022, 61, 622–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.-J.; Liu, P.-Q.; Wu, C.-L.; Wang, K. Effect of dry–wet cycle periods on properties of concrete under sulfate attack. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Jin, Z.; Chang, H.; Zhang, W. A review of chloride transport in concrete exposed to the marine atmosphere zone environment: Experiments and numerical models. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, G.; He, T.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xie, W. A review on chloride transport model and research method in concrete. Mater. Res. Express 2023, 10, 042002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.-F.; Hu, Z.; Wang, X.-E.; Zhao, H.; Qian, K.; Li, L.-J.; Meng, Z. Numerical study on cracking and its effect on chloride transport in concrete subjected to external load. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 325, 126797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Chen, K.; Hu, S.; Chen, J.; Wu, R.; Jin, W. Experimental and numerical study on the microstructure and chloride ion transport behavior of concrete-to-concrete interface. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 367, 130317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, G.; Zhu, G. The durability of basalt-fiber-reinforced cement mortar under exposure to unilateral salt freezing cycles. Front. Mater. 2023, 10, 1202889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kharabsheh, B.N.; Arbili, M.M.; Majdi, A.; Alogla, S.M.; Hakamy, A.; Ahmad, J.; Deifalla, A.F. Basalt fiber reinforced concrete: A compressive review on durability aspects. Materials 2023, 16, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Guo, Y.; Zhao, J.; Hao, T.; Sun, Q. Degradation Behavior of Surface Wear Resistance of Marine Airport Rigid Pavements. Materials 2026, 19, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010054

Guo Y, Zhao J, Hao T, Sun Q. Degradation Behavior of Surface Wear Resistance of Marine Airport Rigid Pavements. Materials. 2026; 19(1):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010054

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Yuming, Jingxuan Zhao, Tiancong Hao, and Qingya Sun. 2026. "Degradation Behavior of Surface Wear Resistance of Marine Airport Rigid Pavements" Materials 19, no. 1: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010054

APA StyleGuo, Y., Zhao, J., Hao, T., & Sun, Q. (2026). Degradation Behavior of Surface Wear Resistance of Marine Airport Rigid Pavements. Materials, 19(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010054