Research Progress on Asphalt–Aggregate Adhesion Suffered from a Salt-Enriched Environment

Abstract

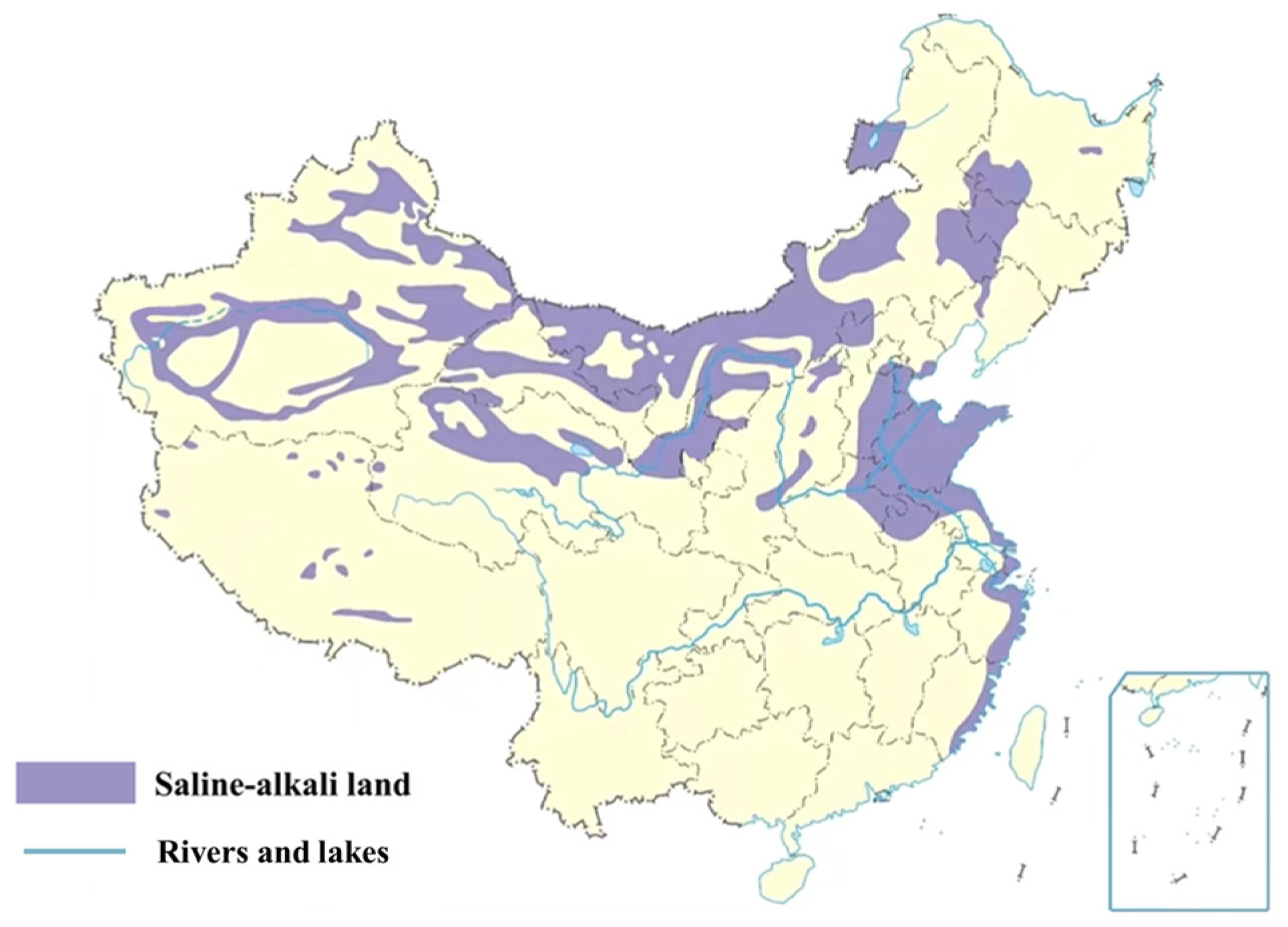

1. Introduction

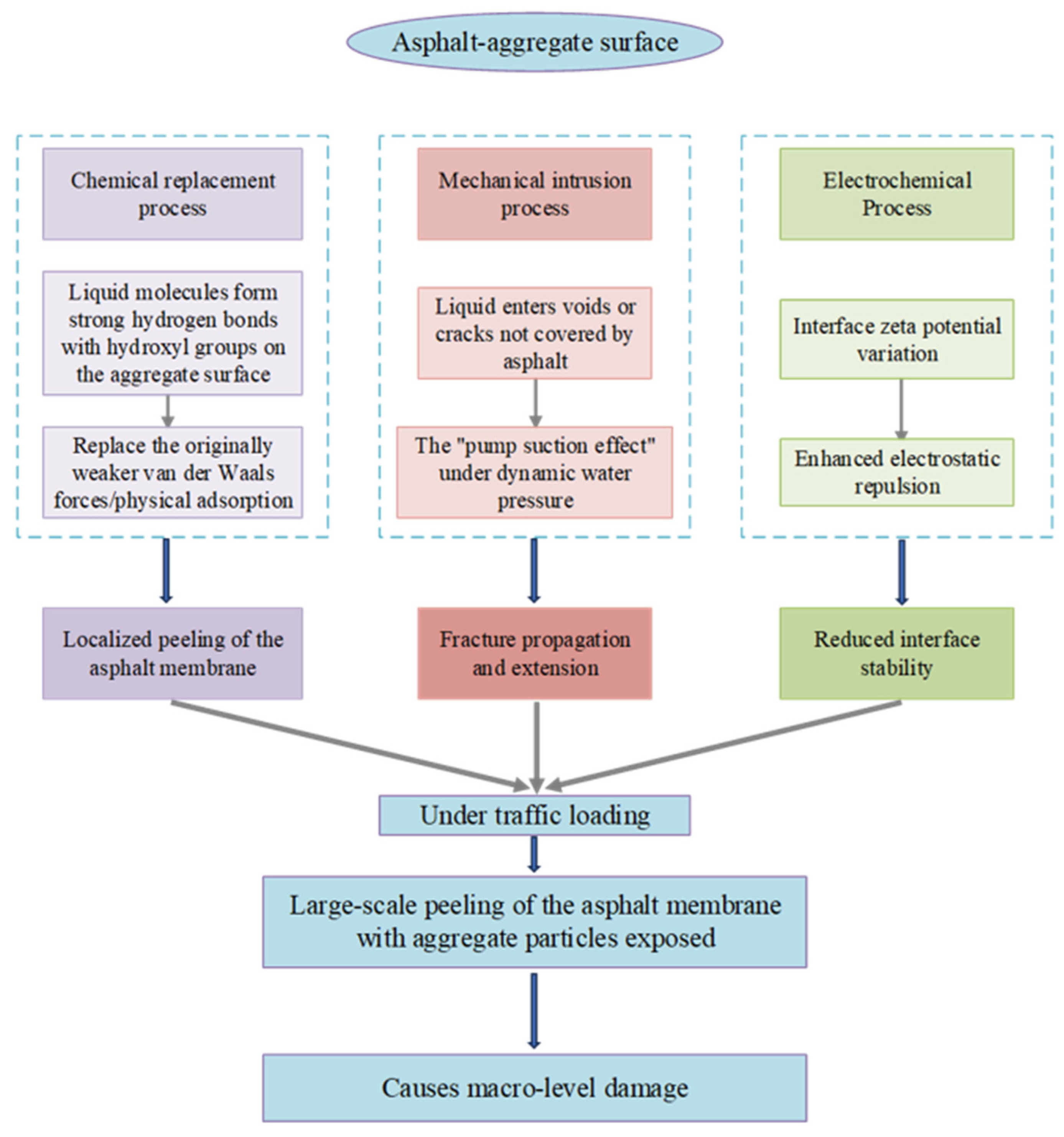

2. The Effect of Salt Enrichment on the Adhesion of Asphalt to Aggregate

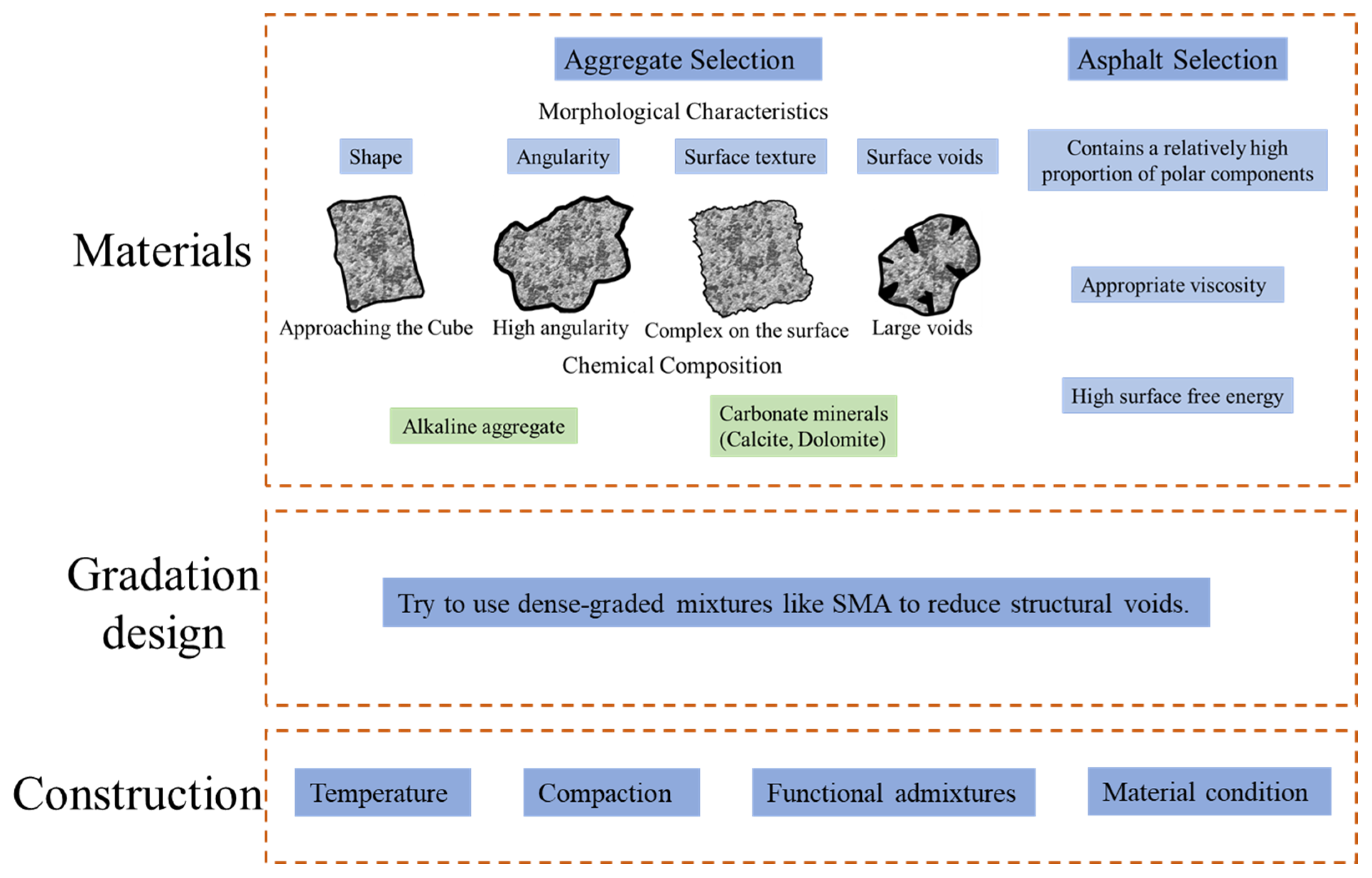

2.1. Aggregate Properties

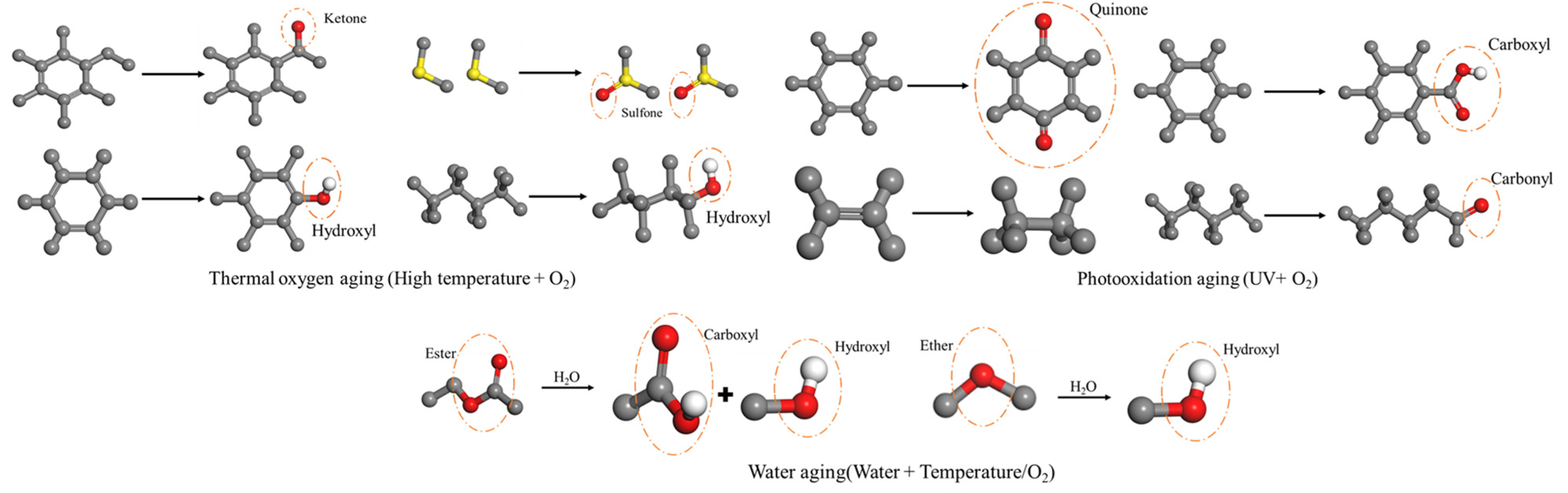

2.2. Chemical Composition of Asphalt

2.3. External Environmental Influences

3. Evaluation Methods for Asphalt–Aggregate Bonding

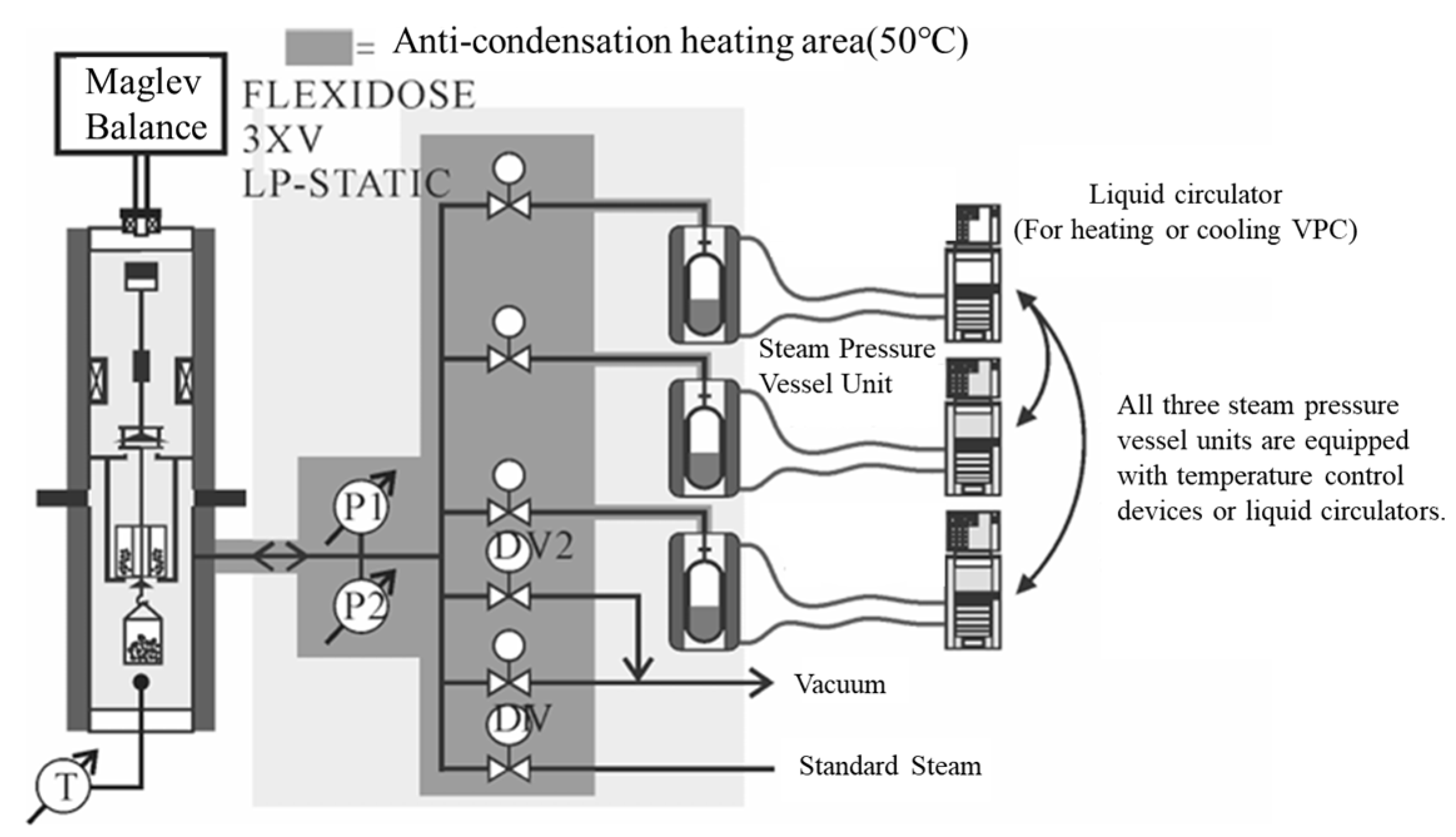

3.1. Laboratory Test Methods

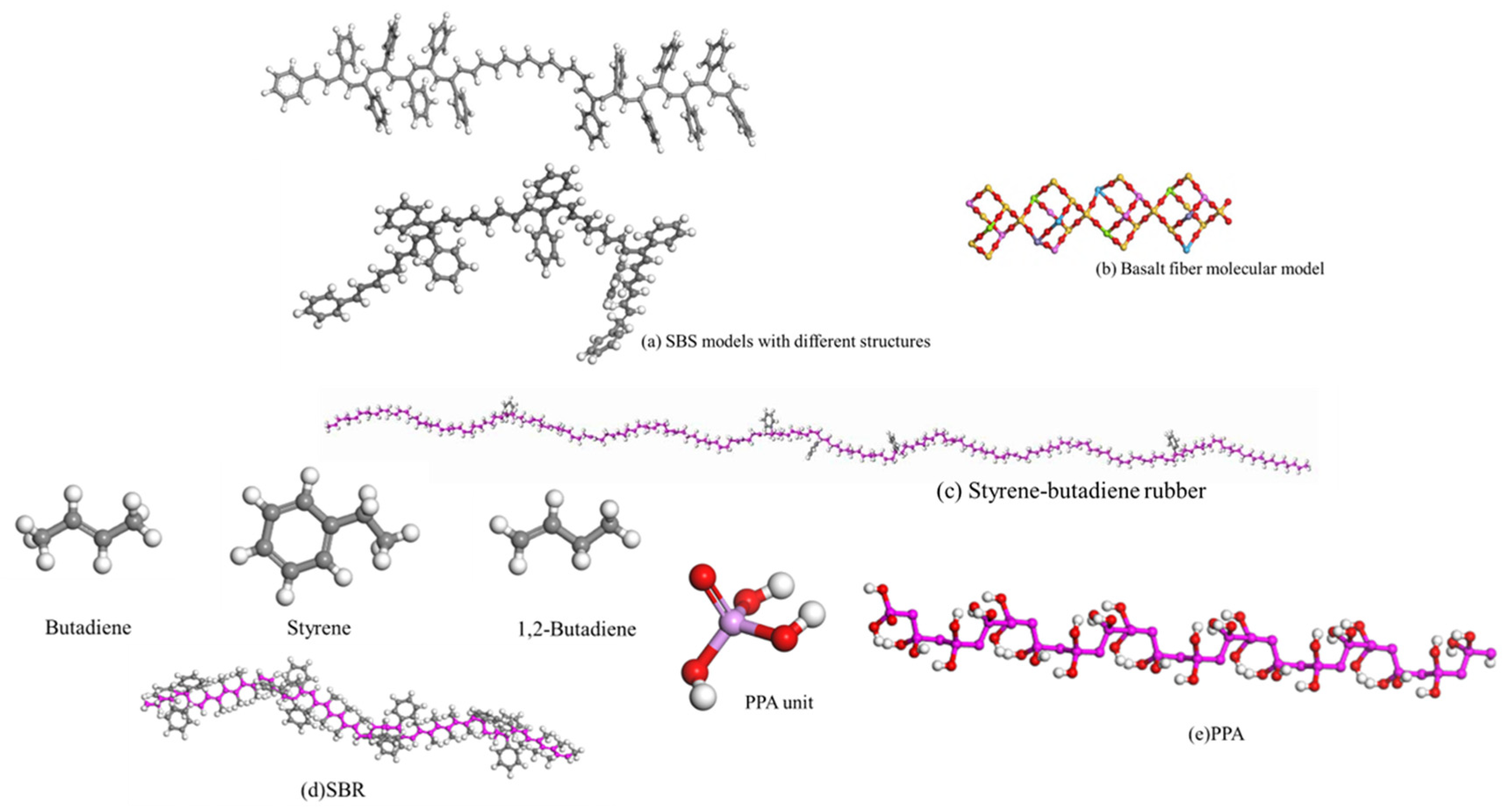

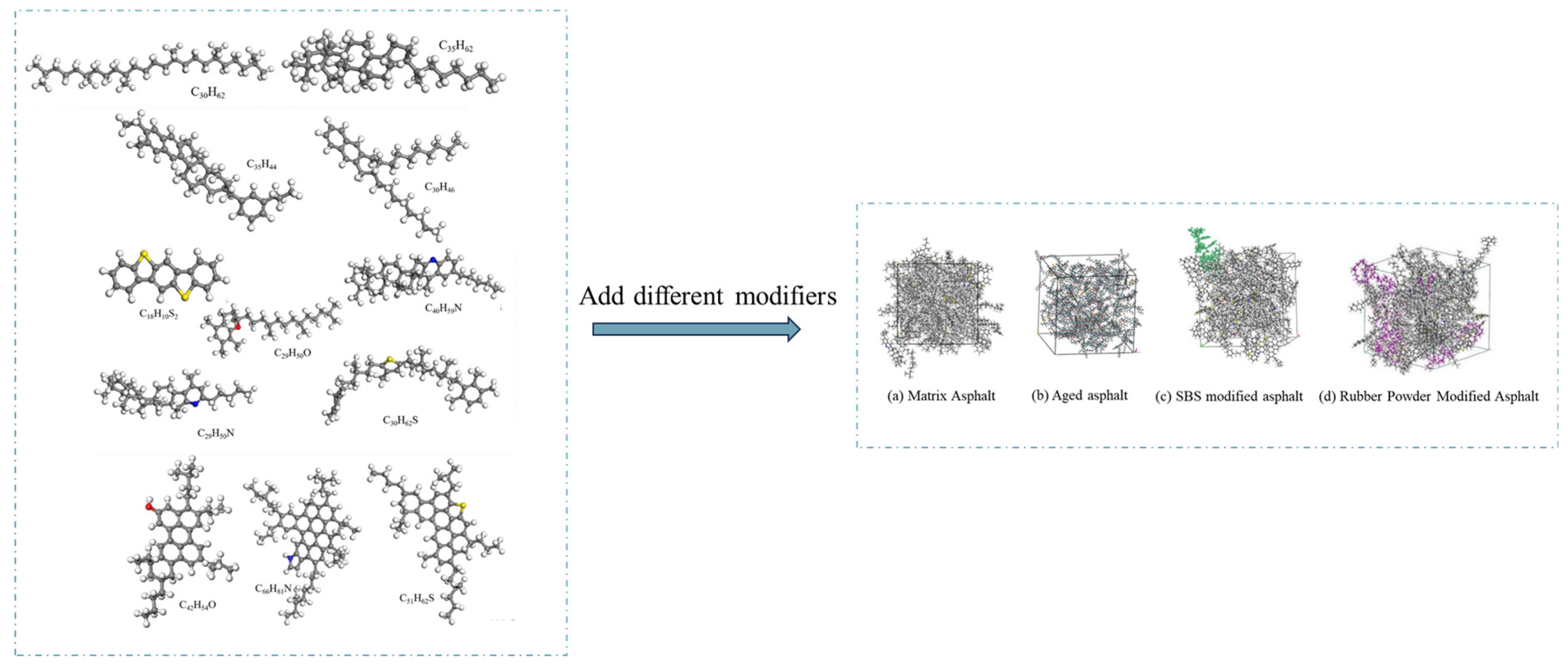

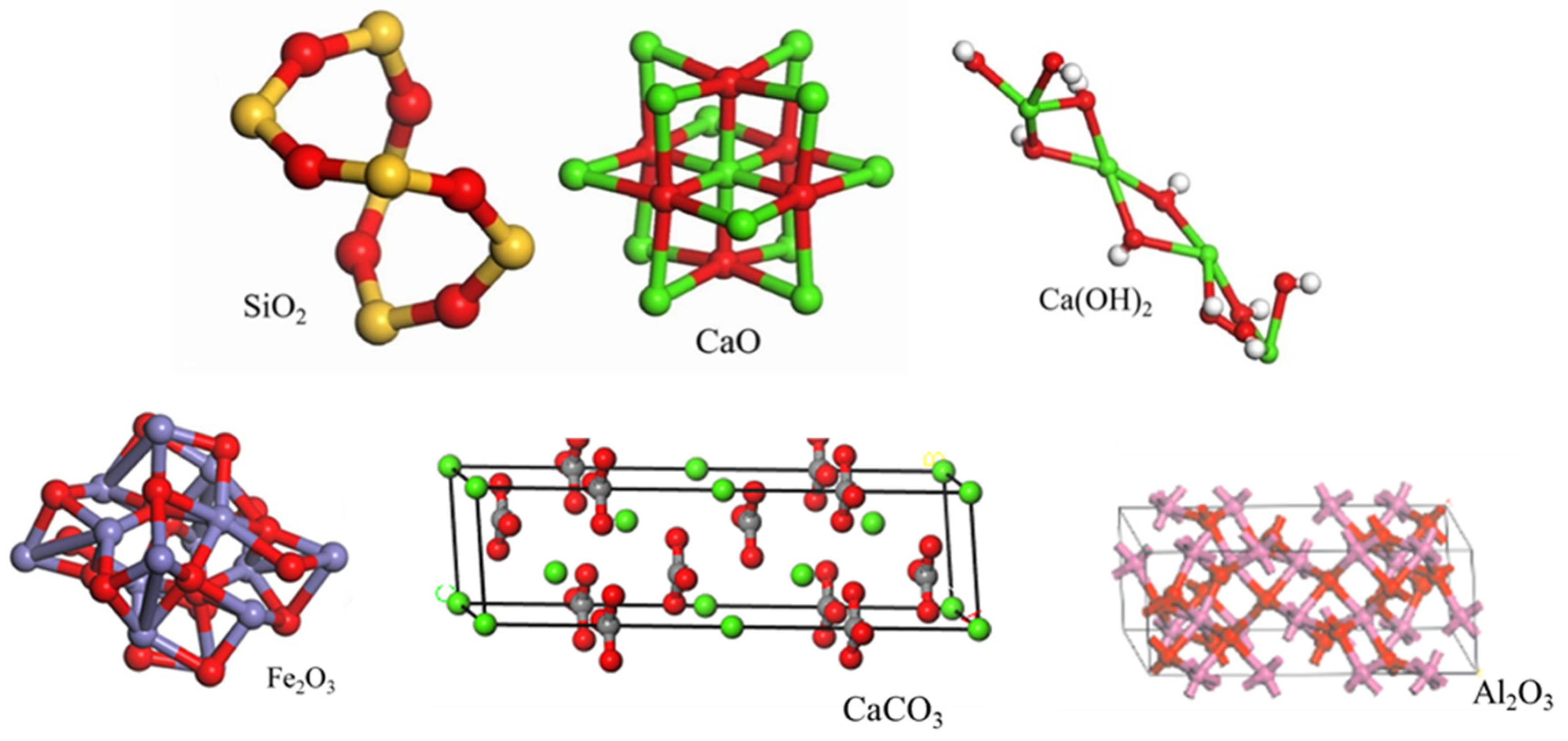

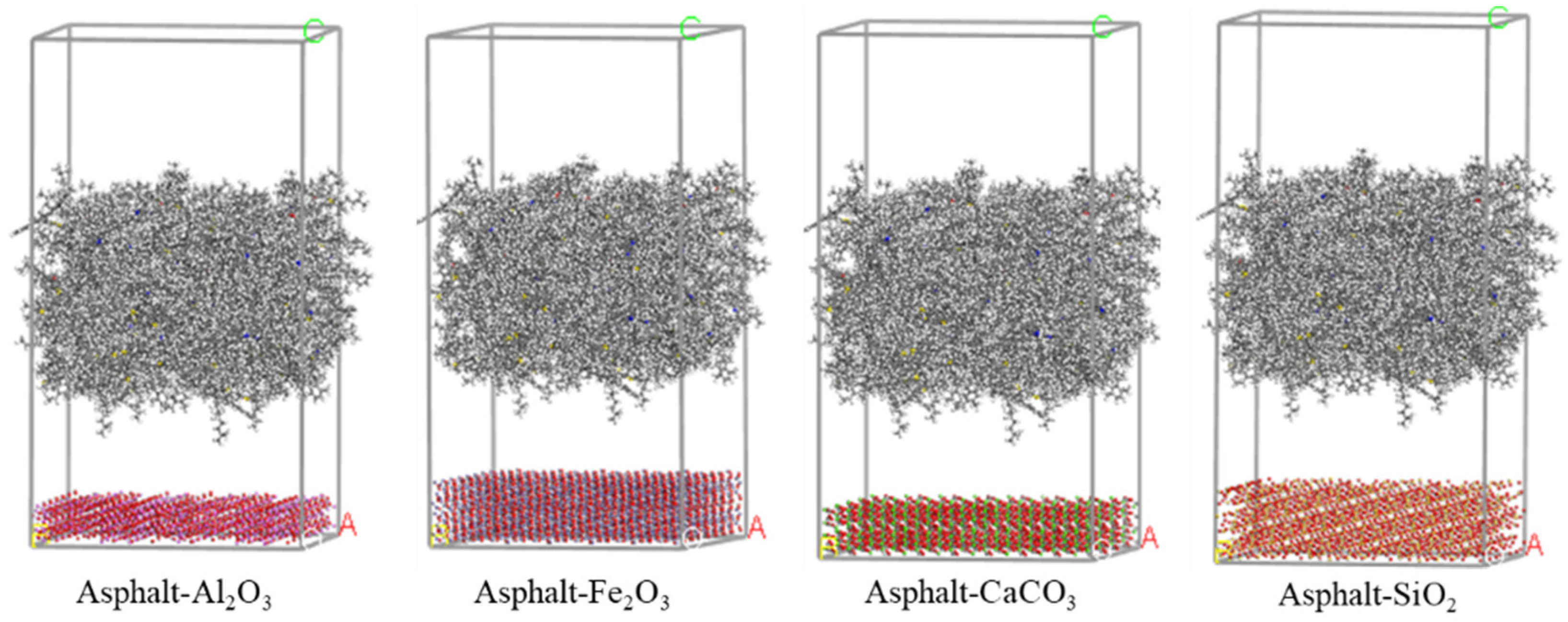

3.2. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

3.3. Aggregate–Asphalt Bonding Performance Prediction

4. Improvement Measures

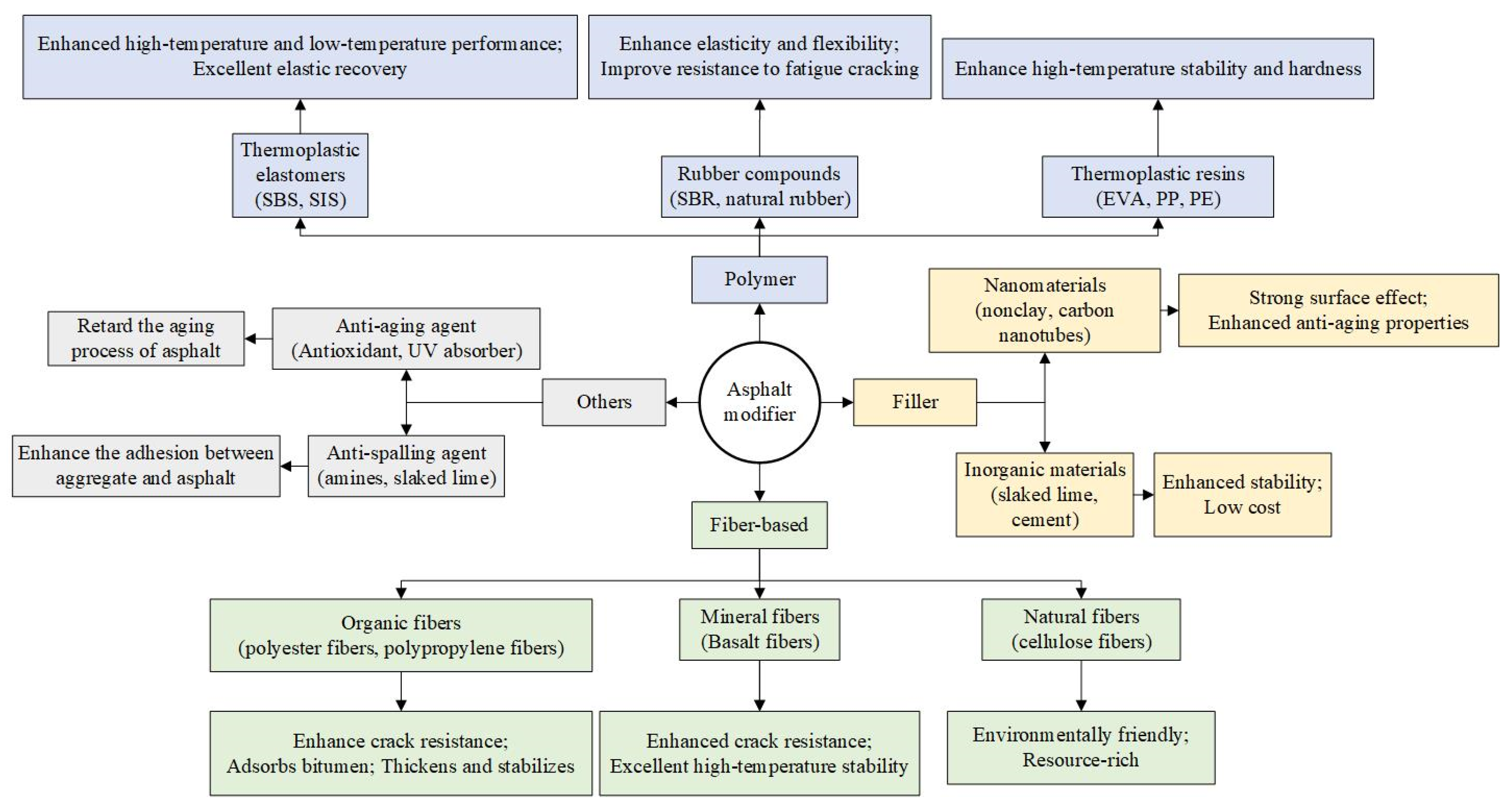

4.1. Asphalt Modification

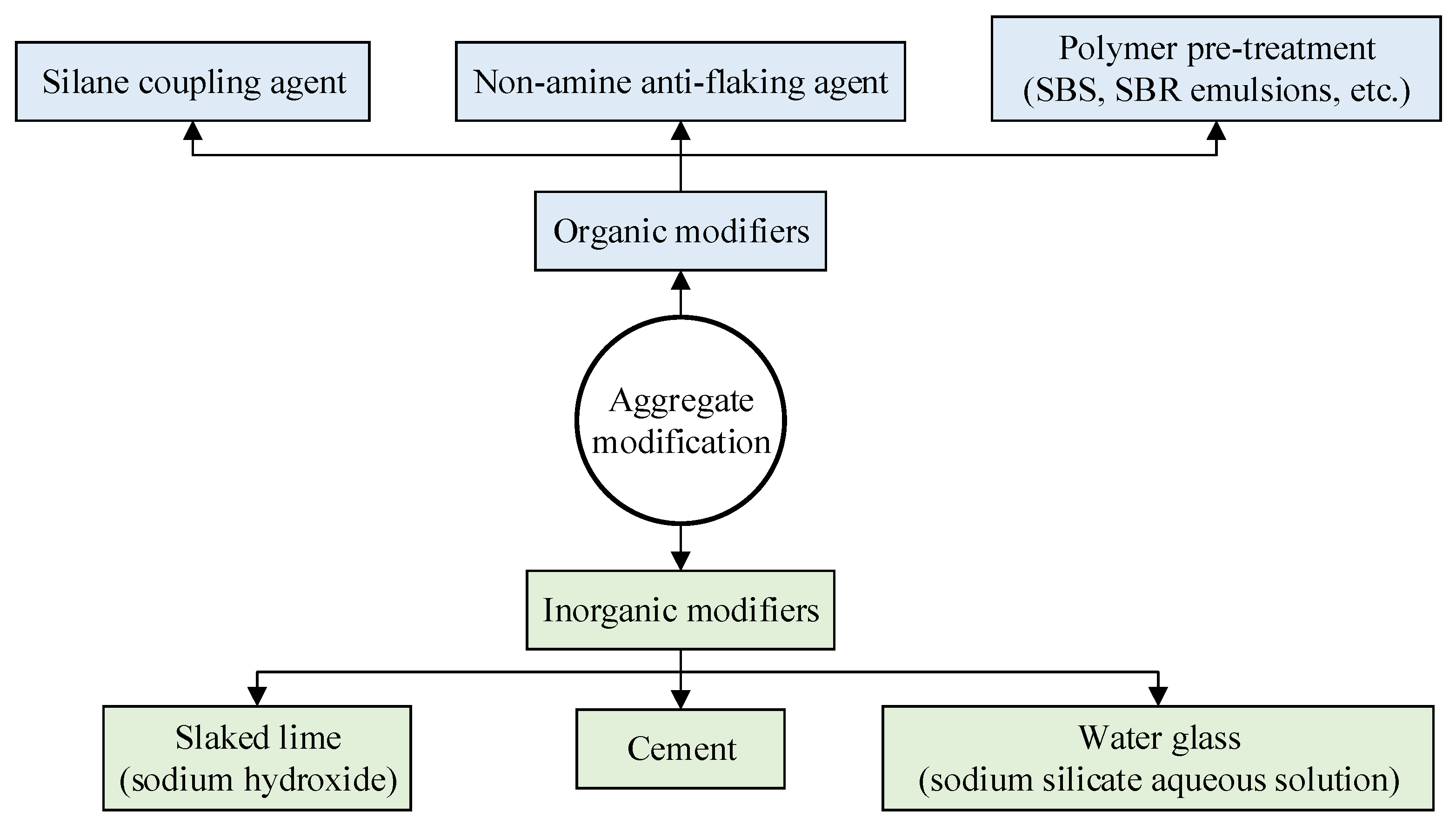

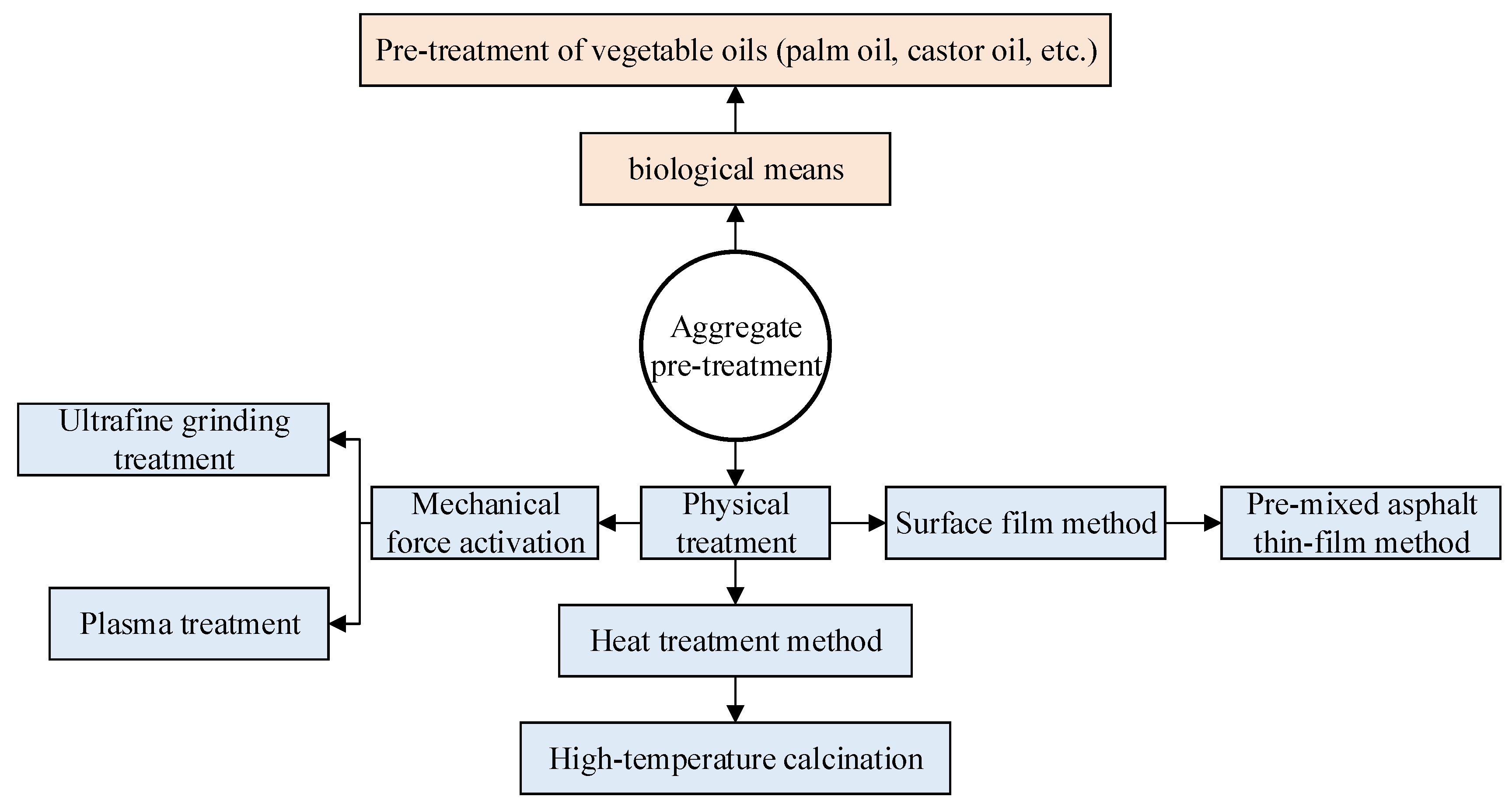

4.2. Aggregate Modification

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cong, P.; Guo, X.; Ge, W. Effects of moisture on the bonding performance of asphalt-aggregate system. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 295, 123667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ren, D.; Tian, G.; Ali, R.; Ai, C. Investigation on moisture damage resistance of asphalt pavement in salt and acid erosion environments based on Multi-scale analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 366, 130177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Chu, Z.; Fang, C.; You, Z.; Cui, S. Progress of Multi-scale Research on Chloride Salt Erosion Damage of Asphalt and Asphalt Mixture. China J. Highw. Transp. 2023, 36, 77–106. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, B.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Ji, K.; Li, L.; Xiong, R. The durability of asphalt mixture with the action of salt erosion: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 315, 125749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Huang, Z. High Temperature Properties of SBS Modified Asphalt Mastics in High Temperature and High Humidity Salt Environment. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Eng. Sci.) 2021, 55, 38–45,80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Jia, M.; Jiang, W.; Lou, B.; Jiao, W.; Yuan, D.; Li, X.; Liu, Z. High temperature property and modification mechanism of asphalt containing waste engine oil bottom. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 261, 119977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. Study on Adhesive Properties of Asphalt Aggregate Interface Under Chloride Salt Erosion. Master’s Thesis, Guangxi University, Nanning, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Li, B.; Wang, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y. Research on the Preparation and Properties of Composite Snow-Melting Agent on Road. Appl. Chem. Ind. 2018, 47, 924–927. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Zheng, M.; Chen, W.; Bi, S.; Wang, C.; Li, Y. Salt-dissolved regularity of the self-ice-melting pavement under rainfall. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 204, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, T.; Guo, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X. Evaluation of self-healing properties of asphalt mixture containing steel slag under microwave heating: Mechanical, thermal transfer and voids microstructural characteristics. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 342, 130932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Shen, A.; Guo, Y. Review of slow-release characteristics of salt-storage additives and its impact on long-term deicing and snow melting performance of asphalt pavements. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2025, 1–48. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/61.1494.U.20250226.1726.002 (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Dohaney, W.J.; Innes, J.D. Ice-Free Pavement—Evaluation of Verglimit as a Deicing Agent. Mater. Perform. 1981, 20, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Qian, J.; Guo, R.; Wen, L. Study on performance deterioration of asphalt and asphalt mixtures containing Mafilon under internal salt freeze-thaw cycles. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2025, 52, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.; Chu, C.; Qiao, N.; Wang, L.; Yang, F.; Sheng, Y.; Guan, B.; Niu, D.; Geng, J.; Chen, H. Performance evaluation of asphalt mixture exposed to dynamic water and chlorine salt erosion. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 201, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Li, G.; Gao, Y.; Wang, K.; Dong, Z.; Liu, F.; Zhu, H. Experimental investigation on bonding property of asphalt-aggregate interface under the actions of salt immersion and freeze-thaw cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 206, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Huang, Z. Investigation of the Microcharacteristics of Asphalt Mastics under Dry–Wet and Freeze–Thaw Cycles in a Coastal Salt Environment. Materials 2019, 12, 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, R.; Chu, C.; Guan, B.; Sheng, Y. Performance damage characteristics of asphalt mixture suffered from the sulphate-water-temperature-load coupling action. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2022, 23, 1368–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefer, A.W. Adhesion in Bitumen-Aggregate Systems and Quantification of the Effects of Water on the Adhesive Bond. Doctoral Dissertation, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chandan, C.; Sivalumar, K.; Masad, E.; Fletcher, T. Application of imaging techniques to geometry analysis of aggregate particles: Applications of imaging technologies in civil engineering materials. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2004, 18, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Jia, M. Comprehensive analysis on influences of aggregate, asphalt and moisture on interfacial adhesion of aggregate-asphalt system. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2021, 35, 641–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Study on Asphalt-Aggergate Interface Adhesion Performance Based on Mineral Composition and Its Enhancement Techniques. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Apeagyei, A.K.; Airey, G.D.; Grenfell, J.R.A. Influence of aggregate mineralogical composition on water resistance of aggregate–bitumen adhesion. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2015, 62, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cala, A.; Caro, S.; Lleras, M.; Rojas-Agramonte, Y. Impact of the chemical composition of aggregates on the adhesion quality and durability of asphalt-aggregate systems. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 216, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Zhu, X. Molecular Dynamics Simulation to Investigate the Adhesion and Diffusion of Asphalt Binder on Aggregate Surfaces. Transp. Res. Rec. 2019, 2673, 500–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Chen, H.; Kuang, D.; Song, L.; Wang, L. Effect of chemical composition of aggregate on interfacial adhesion property between aggregate and asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 146, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y. Influence of Slow-Release Anticoagulant on Performance of Asphalt and Asphalt Mixture. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing Jiaotong University, Chongqing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, C.; Wang, T.; Zou, X. Research on the Adhesion Mechanism between Different Lithologic Aggregates and Asphalt. Highway 2024, 69, 295–301. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, L. The Surface Character Analysis of Bitumen and Aggregates and the Evaluation of the Adhesion Between Them. Doctoral Dissertation, Chang’an University, Xi’an, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, L. Study on Mineral Component of Aggregate for Asphalt Mixture Performance. Master’s Thesis, Chang’an University, Xi’an, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Kong, F.; Guo, P. Investigation on Stripping Behavior of Asphalt Film Using Surface Energy Theory and Pull-off Test. Mater. Rep. 2020, 34, 1288–1294. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, C.; Shan, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, T.; Yang, X.; Lv, D. Microscopic adhesion properties of asphalt–mineral aggregate interface in cold area based on molecular simulation technology. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 268, 121151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Luo, Y.; Xie, W.; Wu, J. Evaluation of road performance and adhesive characteristic of asphalt binder in salt erosion environment. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 25, 101593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Bai, X.; Qian, G.; Wang, F.; Li, Z.; Jin, J.; Zhang, Y. Aging Mechanism and Properties of SBS Modified Bitumen under Complex Environmental Conditions. Materials 2019, 12, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, P.; Ding, F.; Liu, C. Effect of Four Components of Asphalt on Adhesion and Cohesion between Asphalt and Aggregate. China Sci. Pap. 2022, 17, 1396–1401. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Q. Effect of Different Chloride Salt Erosion on the Adhesion Performance of Asphalt-Silica Aggregates Interface and the Mechanism. Master’s Thesis, Xiangtan University, Xiangtan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Y.; Wang, L. Study of diffusion characteristics of asphalt-aggregate interface with molecular dynamics simulation. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2021, 22, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Ge, J.; Qian, G.; Shi, C.; Zhang, C.; Dai, W.; Xie, T.; Nian, T. Evaluation of the interface adhesion mechanism between SBS asphalt and aggregates under UV aging through molecular dynamics. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 409, 133995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M. Study on the Adhesion Failure Mechanism and Adhesion Performance Enhancement of Acidic Aggregate-Asphalt Interfaces. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing Jiaotong University, Chongqing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Xiao, F.; Amirkhanaian, S.; Singh, D. Moisture characteristics of mixtures with warm mix asphalt technologies—A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 142, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrara, A.; Khodaii, A. A review of state of the art on stripping phenomenon in asphalt concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 38, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhri, M.; Javadi, S.; Sedghi, R.; Arzjani, D.; Zarrinpour, Y. Effects of deicing agents on moisture susceptibility of the WMA containing recycled crumb rubber. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 227, 116581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, B.; Jia, M.; Li, C.; Zhang, Z. Effect of short-term aging on interface-cracking behaviors of warm mix asphalt under dry and wet conditions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 261, 119885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, F.; Rahman, M.; Chamberlain, D.; Collins, P. Asphalt surface damage due to combined action of water and dynamic loading. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 196, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Yu, H.; Jin, D.; Bai, X.; Gong, X. Different water environment coupled with ultraviolet radiation on ageing of asphalt binder. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2021, 22, 2410–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D. Study on Characteristics of Asphalt Performance Under Different Ultraviolt Radiation Conditions. Master’s Thesis, Changsha University of Science and Technology, Changsha, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh, M.; Pouria, H.; Moghadas, N.F. Fereidoon Moghadas Nejad Advancing asphalt mixture sustainability: A review of WMA-RAP integration. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 103678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Chen, S.; Gao, C.; Wang, Z. AFM-Based Study on Adhesion of Warm Mix Asphalt-Aggregate Systems. J. Change Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci.) 2025, 22, 104–115. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F. Study on The Influence of Sulfate Erosion on the Fatigue Properties of Asphalt and Its Mixtures under Multi-Factor Coupling. Master’s Thesis, Guangxi University, Nanning, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Emulsified Asphalt Cold Recycled Mixture Under Salt Corrosion Environment Road Performance Research. Master’s Thesis, Shihezi University, Shihezi, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Zhu, H. Physical and Chemical Characteristics of Asphalt in Marine Salt Erosion Environments: Study on Adhesion Performance with Aggregates. In Proceedings of the World Transport Congress 2024, Qingdao, China, 26–29 June 2024; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Z.; Guo, N.; Fng, C.; Tan, Y.; You, Z. Research Progress on Performance and Deterioration Mechanism of Asphalt and Asphalt Mixture in Chloride Environment. Mater. Rep. 2023, 37, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Gong, N.; Xing, Y. Researching the Influence Factors of Asphalt Mixture Performance under the Damage of Deicing Salt and Freezing-Thawing Cycles. Funct. Mater. 2016, 47, 4088–4093. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, C.; Liu, K.; Li, K.; Li, L.; Qiao, N.; Jiang, W.; Lei, N.; Xiong, R. Investigation on the Road Performance of Asphalt Mixture Exposed to Salt Erosion. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 37, 3906–3911, 3934. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Hao, G.; Chen, J.; Li, S.; Peng, L.; Jiang, W. Performance Attenuation and Microstructure Evolution of Asphalt Mixtures Under Synergistic Effect of Salinity and Dry-wet Cycling. Plast. Sci. Technol. 2025, 53, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Correns, C.W.; Steinborn, W. Experiments for Measuring and Explaining the So-called Crystallization Strength. Z. Für Krist. 1939, 101, 117–133. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L. Damage Mechanism of Asphalt Binder by Multi-Factor Coupled Aging. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai Institute of Technology, Shanghai, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Luo, R.; Tu, C. Effect of Relative Humidity on the Adhesion Between Asphalt and Aggregate. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. (Transp. Sci. Eng.) 2021, 45, 757–762. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Tang, X.; Xu, C.; Su, J.; Zhang, G.; He, L. Study onWater and Salt Erosion Damage of Asphalt Mortar-Aggregate Interface. Mater. Rep. 2022, 36, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, C. Study on Salt Corrosion Deterioration Characteristics of Asphalt Mixture Under Multi-Factor Action. Master’s Thesis, Chang’an University, Xi’an, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Ma, X.; Chen, J.; Wu, M.; Li, H.; Ye, D. Effect of Moistuer-Aging Coupling Actions on Asphalt Performance. Highway 2021, 66, 275–284. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, R.; Shi, C.; Peng, L.; Qiao, N.; Chu, C. Evaluation of Asphalt Mixture Water Stability Under the Salt-Freeze-Thaw Cycles. Highway 2025, 70, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Ma, C.; Zhang, J.; Fan, Y.; He, L.; Yao, Z. Experimental Investigation of Moisture-Salt Erosion and Multiple Factors Influenceon Asphalt Mortar-Aggregate Interface. Mater. Rep. 2025, 39, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Zeng, Y.; Gao, L. Studt on Effect of Salt Spray Environment on Asphalt MixturePerformance. Hingway Eng. 2020, 45, 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, P.; Fu, R.; Wang, C. Experimental Study on Water Stability of Cotton Straw Fiber Asphalt Mixture Under Dry-Wet-Salt Freeze-Thaw Cycle. J. Tarim Univ. 2025, 37, 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, Z. Deterioration of Mechanical Properties of Asphalt Mixture in Salty and Humid Environment. J. South China Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2015, 43, 106–112. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. Research on Moisture Salt Erosion Damage and Perfprmance Improvement of Asphalt Mortar-Aggregate Interface. Master’s Thesis, Shandong University, Jinan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X. Research on Salt Corrosion Mechanism of Asphalt and Asphalt Mixture in Coastal Environment. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing Jiaotong University, Chongqing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, X.; He, W. Analysis of the Danage Effect of Sea Salt Erosion on Asphalt-Aggregate Interfacial System in Hygrothermal Envionment. J. Build. Mater. 2020, 23, 1430–1439. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Damage Characteristics of SBS Modified Asphalt Materialunder Coupling Action of Salt Freeze-Thaw Cycle and Ultraviolet Radiation. Master’s Thesis, Chang’an University, Xi’an, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q. Study on Water Damage Mechanism of Asphalt Mixture in Multi-Factor Environment of the South Coast. Doctoral Dissertation, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Z.; Pan, L.; Zhang, J.; Lin, X. Molecular Dynamica Simulation of Adhesion Mechanism of Asphalt-Aggregate Interface. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 40, 809–815, 834. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.Y.; Ma, B.; Mao, W.; Si, W.; Wang, X. Review of interfacial adhesion between asphalt and aggregate based on molecular dynamics. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 362, 129642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.D.; Greenfield, M.L. Chemical compositions of improved model asphalt systems for molecular simulations. Fuel 2014, 115, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L. Research on the Performance Enhancement of SBR-Modified Asphalt Using Polyphosphoric Acid Based on Molecular Simulation. Hum. Commun. Sci. Technol. 2025, 51, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Pang, M.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, L. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Polypropylene Modified by Nanosized CalciumCarbonate Grafted Silane Coupling Agent. Plast. Sci. Technol. 2024, 52, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Hui, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, B.; Gu, S. Influence of Salt Corrosion on the Interfacial Adhesion Characteristics of Steelslag-SBS/CR Modified Asphalt. Mater. Rep. 2025, 39, 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Zhu, M.; Hu, M.; Han, P. Atomistic mechanisms of salt-induced interfacial failure in asphalt–aggregate systems under multiphase salt solution/crystal environments: Molecular simulation and laboratory observation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 718, 164909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Zhang, Y. Evaluation of Basalt Fiber Modified Asphalt-Aggregate Interfacial Adhesionand Microscopic Mechanism Research. Mater. Rep. 2025, 1–25. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/50.1078.TB.20250915.1828.004 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Xiang, H.; Wang, Z.; Deng, M.; Tan, S.; Liang, H. Adhesion Characteristics of an Asphalt Binder-Aggregate Interface Based on Molecular Dynamics. Materials 2025, 18, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Si, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, P.; Zhang, K.; Zhu, Y. Multiscale Investigation of Interfacial Behaviors in Rubber Asphalt-Aggregate Systems Under Salt Erosion: Insights from Laboratory Tests and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Materials 2025, 18, 4647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Hui, Y.; Li, B.; Xu, X. Effect of salt erosion on interfacial adhesion of waste tire crumb rubber-modified asphalt mixtures: A molecular dynamics study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 680, 161419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Luo, L.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Y. Effect of chloride salt migration at interfaces on asphalt-aggregate adhesion: A molecular dynamics study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 428, 136310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, P.; Chang, K.; Tang, C.; Qi, H. Kinetic Simulation of Snow Melting Agentson Equilibrium Stability and Adhesion of Asphalt Molecules. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 42, 624–632. [Google Scholar]

- Si, Y. Study on the Mechanical Damage Characteristics and Evolution Mechanism of Rubber Asphalt Mixture Interface Under the Coupling Effect of Salt and Freeze-Thaw. Master’s Thesis, Anhui University of Science and Technology, Huainan, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, E.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, G. Influence of chloride salt erosion on the adhesion of asphalt-aggregate interfaces considering mineral anisotropy: Insights from molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Model. 2024, 30, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J. Research on the Multi-scale Damage Evolution of Asphalt Mixture and Targeted Prevention and Control Measure Under Salt Freeze-Thaw Cycle. Doctoral Dissertation, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, X.; Tang, A.; Zhu, Y.; Kang, L.; Pan, F. Research Progress of Machine Learning in Material Science. Mater. Rep. 2021, 35, 15115–15124. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S. Machine Learning Based Prediction of Warm Mix Recycled Asphalt-Aggregate Adhesion Properties. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing Jiaotong University, Chongqing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y. Study and Prediction of Properties of StyreneMethyl Copolymers/SBS Composite Modified Asphalt and Mixture. Doctoral Dissertation, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, C.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, K.; Shan, L.; Xu, H. Review and Prospect of Genetic Characteristics of Asphalt Mixture Based on Material Genome Method. China J. Highw. Transp. 2020, 33, 76–90. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, A.; Hafeez, I.; Hussan, S.; Jamil, M.B. Predicting the laboratory rutting response of asphalt mixtures using different neural network algorithms. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2022, 23, 1948–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Tang, Y.; Li, L.; Yan, W.; Huang, B.; Qiu, Y. Research on the recurrent neural network-based fatigue damage model of asphalt binder and the finite element analysis development. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 267, 121761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwanuakwa, I.D.; Ali, S.I.A. Artificial Intelligence Prediction of Rutting and Fatigue Parameters in Modified Asphalt Binders. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftekhari, H.; Hayati, P. Predictive modeling of moisture damage in recycled asphalt mixtures: Evaluating chip content and rejuvenating agents. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2025, 10, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babagoli, R.; Rezaei, M. Development of prediction models for moisture susceptibility of asphalt mixture containing combined SBR, waste CR and ASA using support vector regression and artificial neural network methods. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 322, 126430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Hu, Y.; Jin, Q.; Ren, H. Macro-microscopic study on the crack resistance of polyester fiber asphalt mixture under dry-wet cycling and neural network prediction. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifuzzaman, M.; Gazder, U.; Sirin, O.; Alam, M.S.; Al Mamun, A. Modelling of Asphalt’s Adhesive Behaviour Using Classification and Regression Tree (CART) Analysis. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2019, 2019, 3183050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H. Research on Asphalt Fatigue Lifepred Iction Method Considering Rheological Characteristice. Doctoral Dissertation, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, F. Study on The Evolution of Asphalt Mixture Properties and Fine Damage Mechanism Under DynamicWater-Salt Erosion Photothermal Action. Master’s Thesis, Guangxi University, Nanning, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B. Study on the Properties of Asphalt Mixture and Its Failure Mechanism Under Freeze-Thaw Cycles with Deicers. Master’s Thesis, Chang’an University, Xi’an, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. Study on the Properties of Composite Modified Emulsified Asphalt with Polyurethane and DOTP Plasticizer and Its Micro-Surfacing Mixture Performance. Master’s Thesis, Shandong Jiaotong University, Jinan, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Li, B.; Wei, D.; Tu, C.; Wei, X. Adhesion Characteristics of Polyphosphate SBS Modified Asphalt. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 42, 578–586. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, K.; Guo, Y.; Yue, H.; Wang, D.; Peng, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wei, J. Effect of PPA Composite Modification on Asphalt-Aggregate Adhesion and Water Stability. China J. Highw. Transp. 2024, 37, 317–330. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Wei, W.; Cai, J.; Tan, Z. Research on Properties of Polyphosphoric Acid-Rubber Composite Modified Asphalt and Its Mixture. Highway 2023, 68, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y. Study on the Adhesion Properties of Polyphosphoric Acid Modified Asphalt and Aggregates and the Water Atability of the Mixture. Master’s Thesis, Changsha University of Science and Technolog, Changsha, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G. Study on Resistance to Salt Erosion of Sugarcane Fiber/SBS Asphalt and Its Mixture Modified by Polyphosphate. Master’s Thesis, Guangxi University, Nanning, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarty, H.; Sinha, S. Moisture Damage of Bituminous Pavements and Application of Nanotechnology in Its Prevention. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2020, 32, 03120003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Z. Study on the Healing Performance of Nano-Modified Asphalt Based on Surface Energy Theory. Highway 2022, 67, 317–321. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. Study on High and Low Temperature and Self-Healing Properties of Nano-TiO2/OMMT/SBS Modified Asphalt. Master’s Thesis, Jilin Jianzhu University, Changchun, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Z. Study on the Performance of Nanomaterials/SBS Modified Asphalt by Thermal Analysis Method. Master’s Thesis, Changsha University of Science and Technolog, Changsha, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; He, Z.; Tan, L.; Dong, H. Study on the Performance of Nano-SiO2/SBS Modified Asphalt Mixtures. Pet. Asph. 2024, 38, 40–43,59. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, K. Interfacial Bonding-Failure Behavior of Fiber Reinforced Asphalt Mixture Ang the Prediction of Its Crack Resistance Propert. Doctoral Dissertation, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Gao, W.; Luo, W. Study on Interfacial Adhesion Properties of Titanate Modified Basalt Fiber Reinforced Asphalt Mixture. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 49, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Baldino, N.; Angelico, R.; Caputo, P.; Gabriele, D.; Rossi, C.O. Effect of high water salinity on the adhesion properties of model bitumen modified with a smart additive. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 225, 642–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, H.; Liu, X.; Cheng, J. Multi-scale investigation on water stability and anti-aging performance of granite asphalt mixture modified with composite anti-stripping agents. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 453, 139031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, J.; Geng, J. Study on the Performance of New Type Stone Interface Modifieron Crushed Pebble Asphalt Mixture. Highw. Eng. 2023, 48, 131–135. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, R.; He, Z.; Zhang, X.; He, P. Interfacial Performance of Coupling Agent Modified Asphalt and Egg Crushed Stone Aggregate. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 36, 2689–2694. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, C.; Chen, P.; You, Z.; Lv, S.; Zhang, R.; Xu, F.; Zhang, H.; Chen, H. Effect of silane coupling agent on improving the adhesive properties between asphalt binder and aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 169, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, H. Effect of Silane Coupling Agent on Improving Adhesive Property between Acidic Aggregate and Hydraulic Asphalt. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2021, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Yu, X.; Dong, F.; Ji, Z.; Wang, J. Using Silane Coupling Agent Coating on Acidic Aggregate Surfaces to Enhance the Adhesion between Asphalt and Aggregate: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Materials 2020, 13, 5580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Huang, T.; Lv, S.; Zheng, J. Effect and mechanism of acidic aggregate surface silane modification on water stability of asphalt mixture. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2021, 22, 1654–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H. Research on Effect of Snow Melting Agent Erosion on Performance of Asphalt Concrete and Methods for Its Corrosion Resistance. Master’s Thesis, Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Common Aggregate Types | Principal Mineral Composition | Principal Chemical Composition |

|---|---|---|

| limestone | Calcite, dolomite, magnesite | CaCO3, MgO, Fe2O3 |

| basalt | Pyrite, plagioclase, olivine | SiO2, Al2O3, Fe2O3 |

| granite | Quartz, potassium feldspar, plagioclase feldspar | SiO2, Al2O3, K2O |

| dolomite | Quartz, feldspar, pyroxene | CaCO3, MgO, SiO2 |

| dolerite | Pyroxene, plagioclase, olivine | SiO2, Al2O3, Fe2O3 |

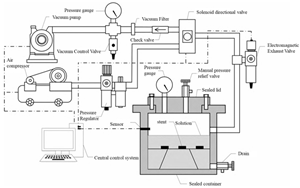

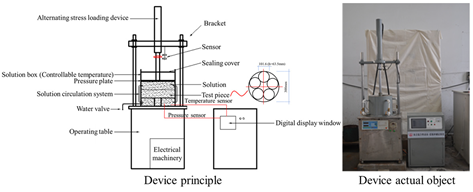

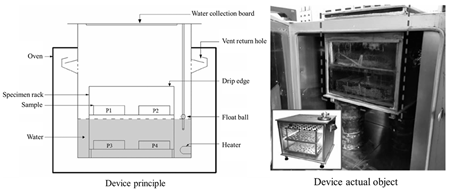

| Instrument Name | Schematic Diagram of the Instrument | Simulated Environment | Control Parameters | Characteristics | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Water Pressure Simulation Apparatus |  | Dynamic water pressure | The magnitude of gas pressure within a sealed container and the duration of its application | Realistic simulation of asphalt–aggregate structures subjected to dynamic hydrostatic pressure erosion, enabling rapid alternating positive and negative pressure cycles for enhanced realism. | Zhang Jizhe, Shandong University [58] |

| Asphalt Mixture Salt Erosion Dynamic Water Scouring Apparatus |  | Erosion by flowing water | Temperature; pressure; number of flushes; flushing medium | Simulates the pumping action of pore water within asphalt mixtures under vehicular loads, thereby compensating for the limitations of static load testing. | Chu Ci, Chang’an University [59] |

| Simulation Apparatus for Coupled Environmental Effects of Water Aging |  | Aging–water damage coupling | Duration of the aging process; temperature; water exposure | Enables precise control of the drip volume, ensuring accurate regulation of the specimen’s water exposure. | Wu Jiantao, Hohai University [60] |

| Asphalt Model | Aggregate Model | Force Field Selection | Indicator | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blend 20% CR and 3% SBS by mass ratio into AAA-1 | CaCO3, 2CaO·SiO2, 3CaO·SiO2 | COMPASS II | Adhesive work; radial relative concentration; mean displacement | Adhesion reduction for CaCO3, C2S, and C3S is 75%, 37%, and 8.9% in water and 86.5%, 66.8%, and 9.8% under salt corrosion, respectively. Salt corrosion enhances CR migration from the steel slag surface, weakening the asphalt–slag interaction and further reducing adhesion [76]. |

| 90# base asphalt, severely aged asphalt, mildly aged asphalt | SiO2 | COMPASS | Fracture energy; interfacial bond strength | Salt solution permeation into the asphalt–aggregate interface markedly reduces bond strength and fracture resistance, posing a more severe threat than water penetration. The conditions governing pull-off, particularly load rate and temperature, play a pivotal role in controlling the mechanical response at the asphalt–aggregate interface [77]. |

| SBS-modified asphalt; basalt fiber; KH550-modified basalt fiber | CaO, SiO2, Al2O3 | COMPASS | Adhesion work; interfacial area; radial distribution function | The incorporation of basalt fibers enhances the adhesion between asphalt and aggregates. When modified with KH550, the adhesion strength increases by 16% compared to the unmodified state, facilitating improved bonding with aggregate oxides [78]. |

| 70# base asphalt; aged base asphalt; SBS-modified asphalt | SiO2, CaCO3 | COMPASS | Adhesion work; peel work; mean displacement and interfacial energy | Alkaline aggregates adhere to asphalt through electrostatic forces, whereas acidic aggregates rely on van der Waals forces, resulting in poorer adhesion. SBS-modified asphalt exhibits optimal adhesion properties, with a significant reduction in adhesion between aged asphalt and aggregates observed [79]. |

| Rubber-modified asphalt; matrix asphalt | CaO, SiO2, Al2O3, Fe2O3 | COMPASS | Mean square displacement; interfacial energy; diffusion coefficient | Water diffusion at the rubber–asphalt–aggregate interface depends on temperature. Compared to SiO2 surfaces, CaO surfaces show a stronger ability to adsorb water. In saline environments, salts are the main cause of degradation. Higher salt concentrations in solutions enhance the diffusion of asphalt components, which weakens interfacial bonding [80]. |

| Rubber-modified asphalt, matrix asphalt, SBS-modified asphalt | CaCO3 | COMPASSII | Adhesion work; mean square displacement; radial relative concentrations; contact angle | Salt solutions are more readily adsorb and disperse on asphalt surfaces than aqueous solutions. This may lead to the dissolution of asphalt polar groups, causing asphalt film cracking and salt solution penetration into the asphalt interior. During salt solution migration, asphalt components redistribute, affecting adhesion performance [81]. |

| Matrix asphalt | SiO2, CaCO3 | COMPASSII | Diffusion coefficient; adhesion work; diffusion thickness; number of hydrogen bonds | Asphalt diffusion is minimal at the aggregate surface and increases with distance from it. Distribution depends on aggregate and solution properties, leading polar components to accumulate at the solution surface, while non-polar ones diffuse differently [82]. |

| Twelve four-component asphalt molecular models; various de-icing agents | CaO, SiO2 | COMPASSII | Interfacial adhesion energy; asphalt concentration on oxide surfaces; adhesion energy ratio | The ingress of a de-icing solution compromises the equilibrium stability of asphalt. Furthermore, once the solution penetrates, it readily forms adsorption bonds with aggregate particle surfaces, leading to aggregate detachment from the asphalt matrix and subsequent adhesion failure [83]. |

| Rubber-modified asphalt; matrix asphalt | SiO2, CaO, Fe2O3, MgO | COMPASS | Isotropic displacement; diffusion coefficient; interfacial energy | The type of aggregate significantly influences the adhesion between the asphalt and aggregate. The greater the number of water molecules in contact, the more severe the damage to adhesive properties. Water molecules displace the asphalt originally present on the aggregate surface, leading to bond failure [84]. |

| AAA-1 asphalt model | SiO2 | COMPASS | Cohesive energy density; free volume fraction; interfacial adhesion energy | Owing to the differing effects of various metal ions on water molecules, sodium salts cause the most pronounced deterioration in the adhesion between asphalt and aggregate following erosion, whilst calcium and magnesium salts exert a lesser influence [35]. |

| Matrix asphalt | SiO2, CaCO3 | COMPASSII | Adhesion energy; debonding energy; degradation ratio (RAD); energy ratio (ER) | The adhesion between asphalt and aggregates diminishes with increasing chloride salt concentration, as chloride solutions spontaneously separate asphalt from aggregates. SiO2 exhibits superior adhesion to asphalt, thereby offering enhanced resistance to chloride salt erosion [85]. |

| Matrix asphalt; bituminous slurry | SiO2, CaCO3 | COMPASSIII | Radial distribution function; mean displacement; adhesion work and diffusion coefficient | Salt molecules compromise the adhesion properties at the degraded asphalt–aggregate interface, with their quantity exhibiting a positive correlation to the extent of interface degradation. Concurrently, decreasing temperatures weaken interfacial interactions, thereby adversely affecting adhesion performance [86]. |

| Material Type | Simulated Environment | Testing Method | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binder asphalt; basalt | Chlorides; sulphates; freeze–thaw cycles | Pull-out test; splitting test; microstructural analysis | Salt concentration and freeze–thaw cycles show a strong positive correlation with adhesion properties, with chloride salts having more destructive potential than sulfate salts [61]. |

| 70# base asphalt; basalt; granite | 3.5% coarse salt solution simulating seawater; 0.5 MPa water pressure | Rheological properties test; moisture absorption rate test; pull-out test | Salt accelerates water ingress into structures, and the action of water pressure facilitates water reaching the adhesive interface, thereby accelerating the process of adhesive failure [58]. |

| 70# base asphalt; basalt; granite | 3.5% coarse salt solution simulating seawater; hydrostatic pressure; wet–dry cycles; freeze–thaw cycles | Dynamic hydrostatic pressure/wet–dry cycle/freeze–thaw cycle erosion test; pull-out test | Water–salt erosion significantly degrades asphalt–aggregate adhesion, most markedly under dynamic water pressure. Moreover, salt–freeze–thaw or wet–dry cycles cause greater weakening than their water-only counterparts [62]. |

| 90# base asphalt, basalt; limestone powder | Chloride salts; sulphate salts; hydrostatic scouring | Dynamic water scouring/wet–dry cycling/freeze–thaw cycling; pull-out tests; normal-temperature/low-temperature splitting tests | Dynamic water scouring is more detrimental to adhesion than static erosion, with pull-off strength showing a significant negative correlation to freeze–thaw cycles. This weakening of the asphalt–aggregate bond heightens susceptibility to water damage [59]. |

| High-viscosity modified asphalt; basalt; limestone mineral powder | Water; thermal-oxygen aging environment | Rotational viscosity testing; surface tension; FTIR testing | Although the combined effect of moisture and thermal oxidation initially increases asphalt viscosity, prolonged aging still degrades mechanical properties, primarily as a function of water content [60]. |

| Base asphalt; SBS-modified asphalt; limestone | Salt spray environment (5% NaCl solution); freeze–thaw cycles | Freeze–thaw splitting test; freeze–thaw cycle splitting test | The tensile and splitting strength of asphalt mixtures declines under combined salt spray and freeze–thaw cycles, primarily driven by salt crystallization and ice expansion pressures within material voids, which severely degrade the asphalt–aggregate interface [63]. |

| Cotton straw fiber; 90# base asphalt; basalt fiber | Composite salt solution (NaCl and Na2SO4); Na2SO4 solution; wet–dry and freeze–thaw cycles | Dry–wet–salt and freeze–thaw cycle splitting test; SEM testing; infrared spectroscopy testing | While salt accelerates the deterioration of the asphalt mixture, both cotton straw and chopped basalt fibers significantly enhance it. The degradation mechanism involves salt solution permeation during cyclic processes, which degrades the asphalt matrix and leads to bond failure [64]. |

| SBS-modified asphalt; basalt; limestone powder; non-amine anti-stripping agent | NaCl solutions of varying concentrations; freeze–thaw cycles; wet–dry cycles; continuous immersion | Void content and splitting strength of mixture specimens | Although freeze–thaw/soaking cycles increase porosity and reduce splitting strength, most severely with a 10% NaCl solution after 10 cycles, basalt fibers effectively enhance the mechanical properties of the mixture [65]. |

| SBS-modified asphalt; basalt; limestone | Slow-release anti-icing agent (primarily composed of NaCl) | Dynamic shear rheometric; low-temperature flexural rheology; contact angle measurement | Slow-release anti-icing agents enhance the hydrophobicity of asphalt, leading to a reduction in the adhesive work between asphalt and aggregates. Concurrently, the cohesive strength within the asphalt also diminishes to some extent. Ultimately, this results in the failure of the asphalt–aggregate bond, causing aggregate loss [26]. |

| 70# base asphalt; limestone; basalt; granite | 3.5% industrial coarse salt solution; dynamic water pressure; static water erosion; wet–dry cycles | Water boiling method; pull-out test, CT scanning; SEM | Salt accelerates water ingress into the asphalt binder matrix. The osmotic pressure generated by the infiltrating salt solution, coupled with the expansive stress from crystallization, hastens the deterioration of adhesion and the decline in mechanical properties of the asphalt mixture [58,66]. |

| 70# base asphalt; SBS-modified asphalt; high-viscosity modified asphalt (TPS); limestone | Wet–dry and freeze–thaw cycles; salt solution | Dynamic shear rheometric; pull-out test; contact angle measurement | The surface energy of asphalt and the adhesion work between the asphalt and aggregate decrease with increasing salt–erosion cycles; high-surface-energy aggregate particles are more prone to detachment from the asphalt matrix via adsorbed water [67]. |

| SBS composite modified asphalt (high-viscosity asphalt); basalt | Sodium chloride solution; sodium sulphate solution; composite salt solution; hydrostatic immersion; wet–dry cycle | Water-boiling method; tensile test; microstructural analysis | Both the surface tension and corrosive properties of seawater degrade the asphalt–aggregate interface. The corrosive effect of sulphate solutions is more pronounced than that of chloride and mixed salt solutions [68]. |

| SBS-modified asphalt; limestone; manufactured sand | Sodium chloride solution; calcium chloride solution; freeze–thaw cycles; ultraviolet aging; salt–freeze cycles; ultraviolet aging | Micro-testing; freeze–thaw splitting test; rutting test | Salt corrosion hardens asphalt, whereby subsequent NaCl penetration and crystallization, combined with ice expansion stresses during freeze–thaw cycles and UV aging, induce interfacial failure and, consequently, pavement defects [69]. |

| Materials | Initial State (MPa) | Experimental Conditions | Final State (MPa) | Decrease Ratio (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90# base asphalt; basalt | Freeze–thaw cycle 7 times: 1.4 | 10% Na2SO4 | 1.05 | 25.00 | [59] |

| 20% NaCl | 0.95 | 32.14 | |||

| Freeze–thaw cycle 28 times: 1.42 | 10% Na2SO4 | 0.98 | 30.99 | ||

| 20% NaCl | 0.92 | 35.21 | |||

| SBS-modified asphalt; basalt | Soak in water for 8 h: 1.467 | 5% NaCl | 1.301 | 11.11 | [68] |

| 10% NaCl | 1.480 | −0.89 | |||

| 5% Na2SO4 | 1.091 | 25.63 | |||

| 5% composite (Cl−:SO42− = 7:1) | 1.205 | 17.86 | |||

| Soak in water for 6 days: 0.766 | 5% NaCl | 0.656 | 14.36 | ||

| 10% NaCl | 0.852 | 11.23 | |||

| 5% Na2SO4 | 0.541 | 29.37 | |||

| 5% composite (Cl−:SO42− = 7:1) | 0.642 | 16.19 |

| Materials | Initial State (ER1) | Experimental Conditions | Final State (ER1) | Decrease Ratio (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70# base asphalt; SBS-modified asphalt; limestone; compound salt solution (NaCl:Na2SO4 = 1:8) | Base asphalt: 0.96 | Wet–dry freeze–thaw cycle 5 times | 0.85 | 11.46 | [67] |

| Wet–dry freeze–thaw cycle 10 times | 0.74 | 22.92 | |||

| Wet–dry freeze–thaw cycle 15 times | 0.61 | 36.46 | |||

| Wet–dry freeze–thaw cycle 20 times | 0.56 | 41.67 | |||

| SBS-modified asphalt: 1.21 | Wet–dry freeze–thaw cycle 5 times | 1.06 | 12.40 | ||

| Wet–dry freeze–thaw cycle 10 times | 0.89 | 26.45 | |||

| Wet–dry freeze–thaw cycle 15 times | 0.77 | 36.36 | |||

| Wet–dry freeze–thaw cycle 20 times | 0.69 | 42.98 |

| Materials | Initial State (ER2) | Experimental Conditions | Final State (ER2) | Decrease Ratio (%) | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | B | ||||||

| Base asphalt; SBS-modified asphalt; limestone; basalt | Base asphalt-L: 2.359 Base asphalt-B: 1.7852 | Wet–dry freeze–thaw cycle 8 times (NaCl) | 1.8715 | 1.3769 | 20.67 | 22.87 | [70] |

| Wet–dry freeze–thaw cycle 15 times (NaCl) | 1.5546 | 1.0852 | 34.10 | 39.21 | |||

| Wet–dry freeze–thaw cycle 25 times (NaCl) | 1.3041 | 0.9361 | 44.72 | 47.56 | |||

| Wet–dry cycle 25 times and freeze–thaw cycle 8 times (NaCl) | 1.1094 | 0.7703 | 52.97 | 56.85 | |||

| Wet–dry freeze–thaw cycle 8 times (Na2SO4) | 1.5791 | 1.1459 | 33.06 | 35.81 | |||

| Wet–dry freeze–thaw cycle 15 times (Na2SO4) | 1.2846 | 0.9104 | 45.54 | 49.00 | |||

| Wet–dry freeze–thaw cycle 25 times (Na2SO4) | 0.9013 | 0.7144 | 61.79 | 59.98 | |||

| Wet–dry cycle 25 times and freeze–thaw cycle 8 times (Na2SO4) | 0.6867 | 0.4575 | 70.89 | 74.37 | |||

| SBS-modified asphalt-L: 3.0904 SBS-modified asphalt-B: 2.1104 | Wet–dry freeze–thaw cycle 8 times (NaCl) | 2.5324 | 1.7998 | 18.06 | 14.72 | ||

| Wet–dry freeze–thaw cycle 15 times (NaCl) | 2.3490 | 1.6885 | 23.99 | 19.99 | |||

| Wet–dry freeze–thaw cycle 25 times (NaCl) | 2.0184 | 1.4799 | 34.69 | 29.88 | |||

| Wet–dry cycle 25 times and freeze–thaw cycle 8 times (NaCl) | 1.6392 | 1.1494 | 46.96 | 45.54 | |||

| Wet–dry freeze–thaw cycle 8 times (Na2SO4) | 2.0704 | 1.4857 | 33.01 | 29.60 | |||

| Wet–dry freeze–thaw cycle 15 times (Na2SO4) | 1.8851 | 1.3192 | 39.00 | 37.49 | |||

| Wet–dry freeze–thaw cycle 25 times (Na2SO4) | 1.6694 | 1.2367 | 45.98 | 41.40 | |||

| Wet–dry cycle 25 times and freeze–thaw cycle 8 times (Na2SO4) | 1.4220 | 1.0973 | 55.7 | 49.0 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Deng, W.; Peng, L.; Lai, H.; Zong, Y.; Chang, M.; Xiong, R. Research Progress on Asphalt–Aggregate Adhesion Suffered from a Salt-Enriched Environment. Materials 2026, 19, 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010192

Liu Y, Deng W, Peng L, Lai H, Zong Y, Chang M, Xiong R. Research Progress on Asphalt–Aggregate Adhesion Suffered from a Salt-Enriched Environment. Materials. 2026; 19(1):192. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010192

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yue, Wei Deng, Linwei Peng, Hao Lai, Youjie Zong, Mingfeng Chang, and Rui Xiong. 2026. "Research Progress on Asphalt–Aggregate Adhesion Suffered from a Salt-Enriched Environment" Materials 19, no. 1: 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010192

APA StyleLiu, Y., Deng, W., Peng, L., Lai, H., Zong, Y., Chang, M., & Xiong, R. (2026). Research Progress on Asphalt–Aggregate Adhesion Suffered from a Salt-Enriched Environment. Materials, 19(1), 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010192