Analysis of Physical Processes in Confined Pores of Activated Carbons with Uniform Porosity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Materials

2.1.1. Chemicals

2.1.2. Synthesis of Carbon Materials

2.2. Textural and Structural Characterization of Porous Carbon Materials

2.3. Phase Transition Measurements in Confined Pores

2.4. Dye Adsorption Isotherm and Kinetic Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Textural and Structural Properties of Mesoporous Carbon Materials

3.2. Surface Chemistry of Mesoporous Carbons

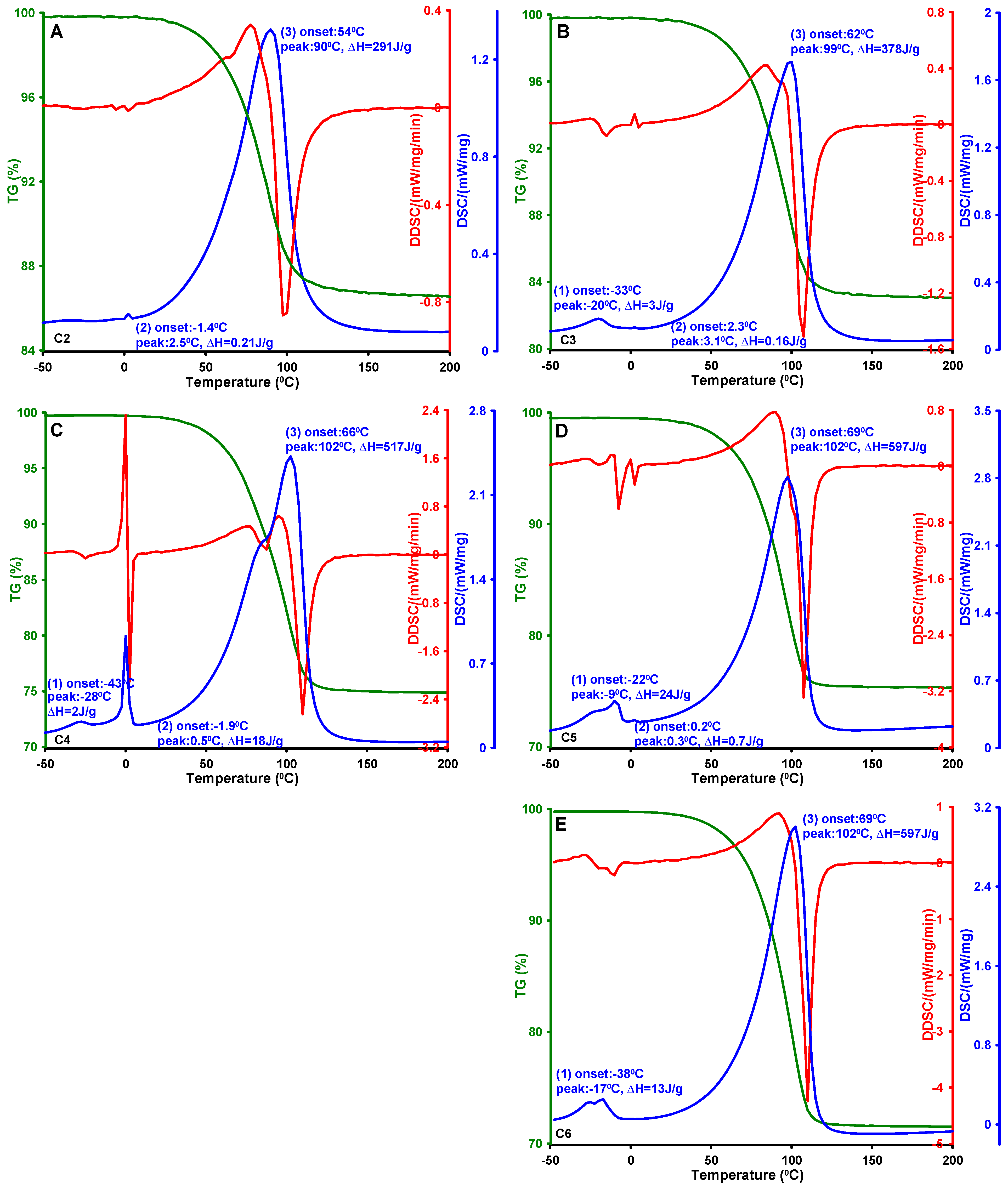

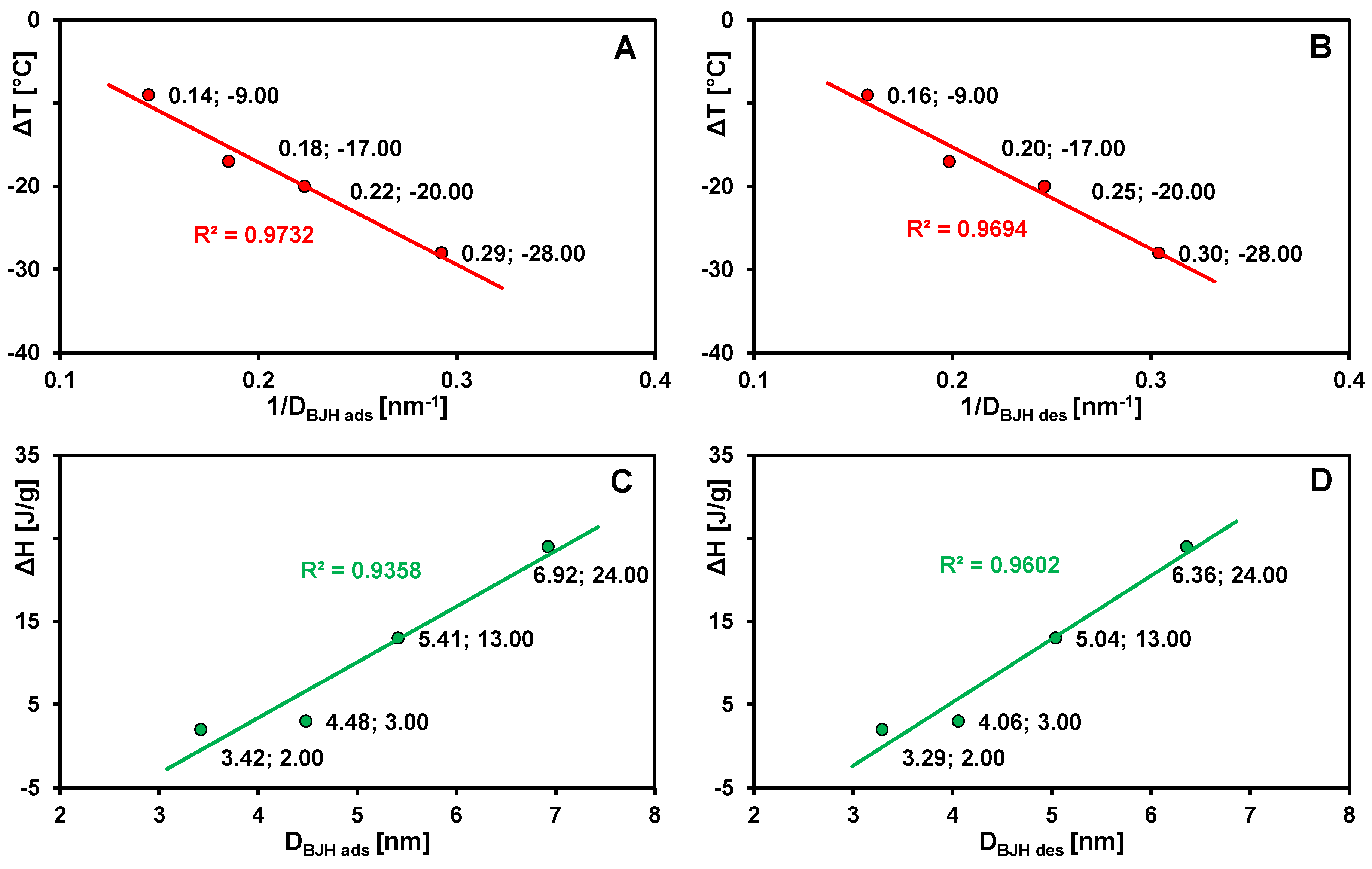

3.3. Phase Transformations in Confined Pore Spaces of Mesoporous Carbon Materials

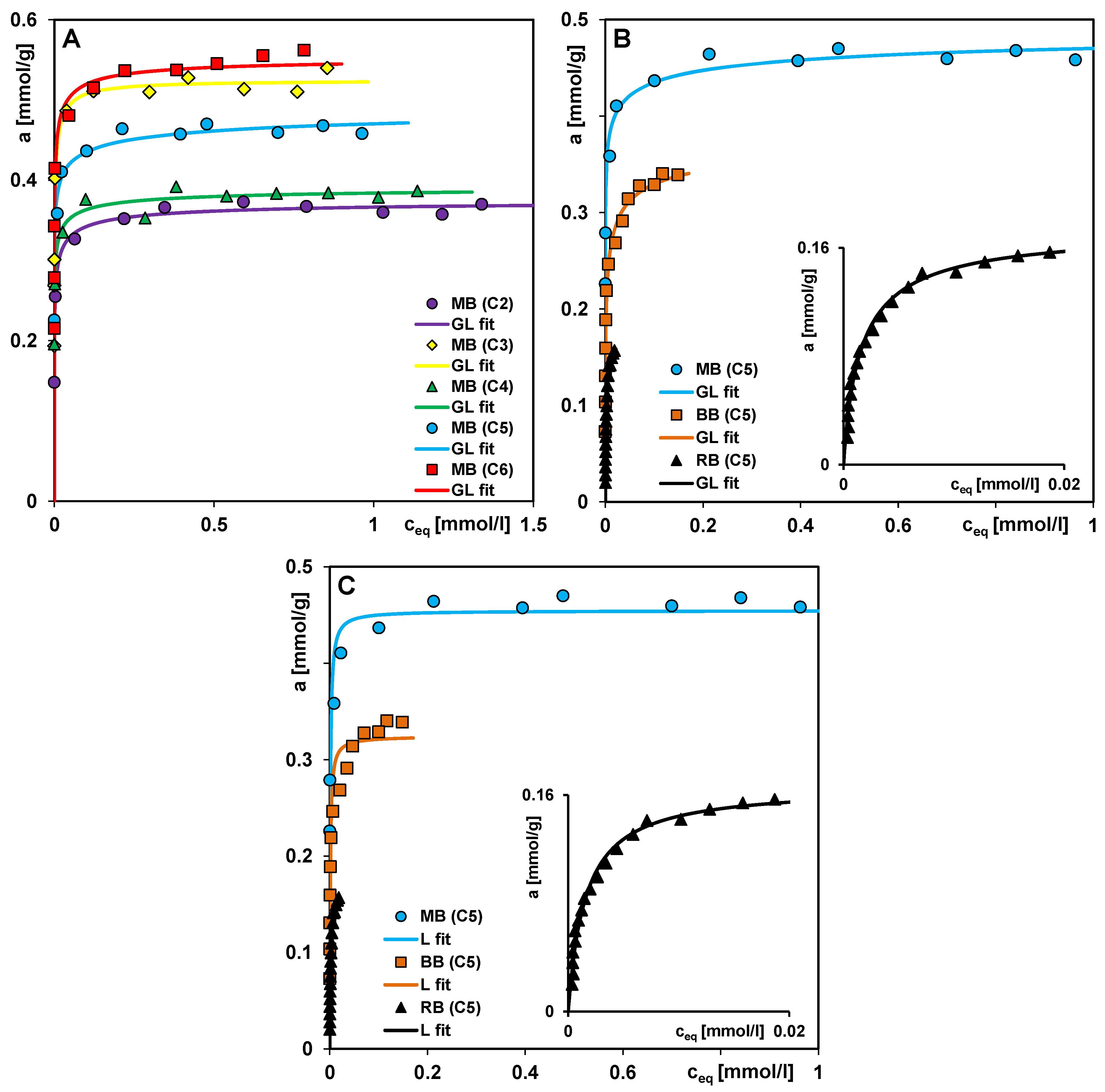

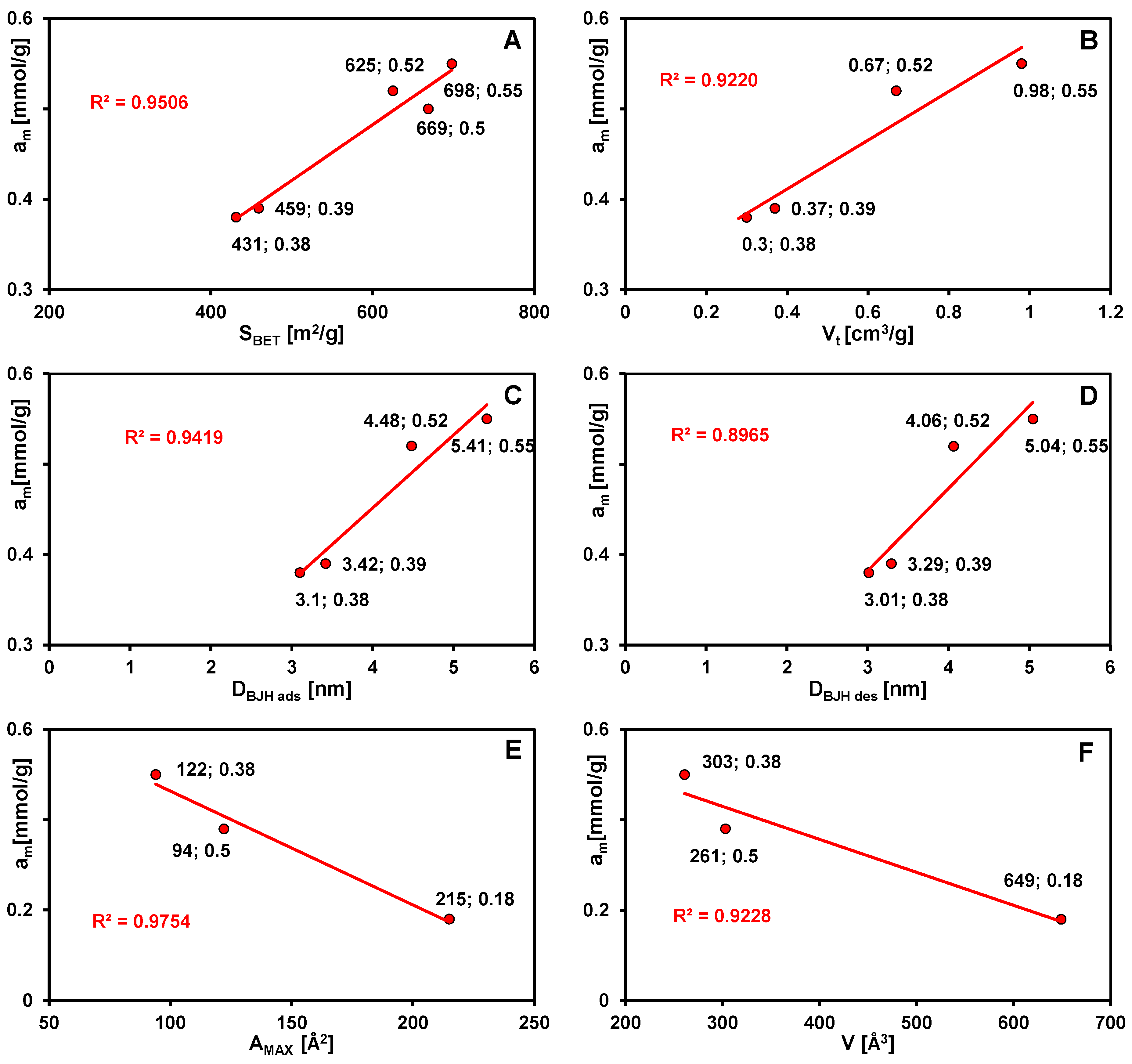

3.4. Adsorption Processes in Porous Carbons

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davis, M.E. Ordered porous materials for emerging applications. Nature 2002, 417, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, B.; Creamer, A.E.; Cao, C.; Li, Y. Adsorption of VOCs onto engineered carbon materials: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 338, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauter, M.S.; Elimelech, M. Environmental Applications of Carbon-Based Nanomaterials. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 5843–5859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Wan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; He, F.; Yu, Z.; Huang, J.; Wang, H.; Ok, Y.S.; Jiang, Y.; Gao, B. Surface functional groups of carbon-based adsorbents and their roles in the removal of heavy metals from aqueous solutions: A critical review. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 366, 608–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Saleh, T.A. Sorption of pollutants by porous carbon, carbon nanotubes and fullerene- An overview. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 2828–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.-W.; Li, F.; Liu, M.; Lu, G.Q.; Cheng, H.-M. 3D Aperiodic Hierarchical Porous Graphitic Carbon Material for High-Rate Electrochemical Capacitive Energy Storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Hyeon, T. Recent progress in the synthesis of porous carbon materials. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 2073–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.; Rodríguez-Reinoso, F. CHAPTER 2—Activated Carbon (Origins). In Activated Carbon; Marsh, H., Rodríguez-Reinoso, F., Eds.; Elsevier Science Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 13–86. [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki, M.; Toyoda, M.; Soneda, Y.; Tsujimura, S.; Morishita, T. Templated mesoporous carbons: Synthesis and applications. Carbon 2016, 107, 448–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S. Synthesis of ordered mesoporous carbon by soft template method. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 81, 842–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Sayari, A. SBA-15 templated-ordered mesoporous carbon: Effect of SBA-15 microporosity. In Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis; Sayari, A., Jaroniec, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 156, pp. 543–550. [Google Scholar]

- Ryoo, R.; Joo, S.H.; Jun, S. Synthesis of highly ordered carbon molecular sieves via template-mediated structural transformation. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 7743–7746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryoo, R.; Joo, S.H.; Kruk, M.; Jaroniec, M. Ordered mesoporous carbons. Adv. Mater. 2001, 13, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olchowski, R.; Dobrowolski, R. Synthesis, properties and applications of CMK-3-type ordered mesoporous carbons. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie-Sklodowska Sect. AA—Chem. 2018, 73, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettelroth, D.; Schwarz, H.-C.; Burblies, N.; Guschanski, N.; Behrens, P. Catalytic graphitization of ordered mesoporous carbon CMK-3 with iron oxide catalysts: Evaluation of different synthesis pathways. Phys. Status Solidi (A) 2016, 213, 1395–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Lu, L.; Kottapalli, A.G.P.; Pei, Y. Status and perspectives of hierarchical porous carbon materials in terms of high-performance lithium–sulfur batteries. Carbon Energy 2022, 4, 346–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, N.M.; Saritha, D.; Dandu, N.K.; Chandaluri, C.G.; Ramesh, G.V. Recent Advances of Biomass-Derived Porous Carbon Materials in Catalytic Conversion of Organic Compounds. In Biomass-Derived Carbon Materials; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 293–315. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, E.; Luong, J.H.T. Carbon Materials as Catalyst Supports and Catalysts in the Transformation of Biomass to Fuels and Chemicals. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 3393–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.-G.; Hu, T.-L. Incorporation of Active Metal Species in Crystalline Porous Materials for Highly Efficient Synergetic Catalysis. Small 2021, 17, 2003971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, W.J.; Gil, B.; Makowski, W.; Marszalek, B.; Eliášová, P. Layer like porous materials with hierarchical structure. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 3400–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Xu, L.; Yue, L.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Hao, Z. Supported Nanometric Pd Hierarchical Catalysts for Efficient Toluene Removal: Catalyst Characterization and Activity Elucidation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 7211–7222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolison, D.R.; Long, J.W.; Lytle, J.C.; Fischer, A.E.; Rhodes, C.P.; McEvoy, T.M.; Bourg, M.E.; Lubers, A.M. Multifunctional 3D nanoarchitectures for energy storage and conversion. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 226–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furmaniak, S.; Gauden, P.A.; Kowalczyk, P.; Patrykiejew, A. Monte Carlo study of chemical reaction equilibria in pores of activated carbons. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 53667–53679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliwinska-Bartkowiak, M.; Gras, J.; Sikorski, R.; Radhakrishnan, R.; Gelb, L.; Gubbins, K.E. Phase Transitions in Pores: Experimental and Simulation Studies of Melting and Freezing. Langmuir 1999, 15, 6060–6069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado-Collados, C.; Majid, A.A.A.; Martínez-Escandell, M.; Daemen, L.L.; Missyul, A.; Koh, C.; Silvestre-Albero, J. Freezing/melting of water in the confined nanospace of carbon materials: Effect of an external stimulus. Carbon 2020, 158, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikovitch, P.I.; Neimark, A.V. Experimental Confirmation of Different Mechanisms of Evaporation from Ink-Bottle Type Pores: Equilibrium, Pore Blocking, and Cavitation. Langmuir 2002, 18, 9830–9837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishige, K. Nature of Adsorption Hysteresis in Cylindrical Pores: Effect of Pore Corrugation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 22508–22514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.W.; Bumstead, H.A.; Gibbs, V.N.R. The Collected Works of J. Willard Gibbs. Nature 1929, 124, 119–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svintradze, D.V. Generalization of the Gibbs-Thomson Equation and Predicting Melting Temperatures of Biomacromolecules in Confined Geometries. Biophys. J. 2021, 120, 201a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, D.G.; Gubbins, K.E.; Radhakrishnan, R.; Sliwinska-Bartkowiak, M. Phase separation in confined systems. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1999, 62, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Smarsly, B.; Groenewolt, M.; Ravikovitch, P.I.; Neimark, A.V. Adsorption Hysteresis of Nitrogen and Argon in Pore Networks and Characterization of Novel Micro- and Mesoporous Silicas. Langmuir 2006, 22, 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, A.; Wilms, D.; Virnau, P.; Binder, K. Capillary condensation in cylindrical pores: Monte Carlo study of the interplay of surface and finite size effects. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 133, 164702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gor, G.Y.; Rasmussen, C.J.; Neimark, A.V. Capillary Condensation Hysteresis in Overlapping Spherical Pores: A Monte Carlo Simulation Study. Langmuir 2012, 28, 12100–12107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilms, D.; Winkler, A.; Virnau, P.; Binder, K. Rounding of Phase Transitions in Cylindrical Pores. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 045701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blachnio, M.; Zienkiewicz-Strzalka, M.; Derylo-Marczewska, A. Mesoporous Silicas of Well-Organized Structure: Synthesis, Characterization, and Investigation of Physical Processes Occurring in Confined Pore Spaces. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruk, M.; Li, Z.; Jaroniec, M.; Betz, W.R. Nitrogen Adsorption Study of Surface Properties of Graphitized Carbon Blacks. Langmuir 1999, 15, 1435–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choma, J.; Górka, J.; Jaroniec, M. Mesoporous carbons synthesized by soft-templating method: Determination of pore size distribution from argon and nitrogen adsorption isotherms. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2008, 112, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, S.S.; Evans, M.J.B.; Halliop, E.; MacDonald, J.A.F. Acidic and basic sites on the surface of porous carbon. Carbon 1997, 35, 1361–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes-Morán, M.A.; Suárez, D.; Menéndez, J.A.; Fuente, E. On the nature of basic sites on carbon surfaces: An overview. Carbon 2004, 42, 1219–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon y Leon, C.A.; Solar, J.M.; Calemma, V.; Radovic, L.R. Evidence for the protonation of basal plane sites on carbon. Carbon 1992, 30, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafeeyan, M.S.; Daud, W.M.A.W.; Houshmand, A.; Shamiri, A. A review on surface modification of activated carbon for carbon dioxide adsorption. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2010, 89, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garten, V.A.; Weiss, D.E.; Willis, J.B. A new interpretation of the Acidic and Basic structures in Carbons. II. The Chromene-carbonium ion couple in Carbon. Aust. J. Chem. 1957, 10, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Qiao, Z.-A. Carbon Surface Chemistry: New Insight into the Old Story. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2206025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Fan, J.; Wang, Y.; Dang, Y.; Heumann, S.; Ding, Y. Insights into the role of defects on the Raman spectroscopy of carbon nanotube and biomass-derived carbon. Carbon 2024, 222, 118998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xiang, P.; Tan, Z.; Tian, Z.; Greiner, M.; Heumann, S.; Ding, Y.; Qiao, Z.-A. Carbon Surface Chemistry: Benchmark for the Analysis of Oxygen Functionalities on Carbon Materials. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2418239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marczewski, A.W.; Jaroniec, M. A new isotherm equation for single-solute adsorption from dilute solutions on energetically heterogeneous solids. Monatshefte Chem./Chem. Mon. 1983, 114, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroniec, M.; Marczewski, A.W. Adsorption from solutions of nonelectrolytes on heterogeneous solid surfaces: A four-parameter equation for the excess adsorption isotherm. Monatshefte Chem./Chem. Mon. 1984, 115, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroniec, M.; Marczewski, A.W. Physical adsorption of gases on energetically heterogeneous solids I. Generalized Langmuir equation and its energy distribution. Monatshefte Chem./Chem. Mon. 1984, 115, 997–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroniec, M.; Marczewski, A.W. Physical adsorption of gases on energetically heterogeneous solids II. Theoretical extension of a generalized Langmuir equation and its application for analysing adsorption data. Monatshefte Chem./Chem. Mon. 1984, 115, 1013–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derylo-Marczewska, A.; Blachnio, M.; Marczewski, A.W.; Seczkowska, M.; Tarasiuk, B. Phenoxyacid pesticide adsorption on activated carbon—Equilibrium and kinetics. Chemosphere 2019, 214, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachnio, M.; Derylo-Marczewska, A.; Seczkowska, M. Influence of pesticide properties on adsorption capacity and rate on activated carbon from aqueous solution. In Sorption in 2020s; Kyzas, G., Lazaridis, N., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Derylo-Marczewska, A.; Blachnio, M.; Marczewski, A.W.; Swiatkowski, A.; Buczek, B. Adsorption of chlorophenoxy pesticides on activated carbon with gradually removed external particle layers. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 308, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachnio, M.; Derylo-Marczewska, A.; Charmas, B.; Zienkiewicz-Strzalka, M.; Bogatyrov, V.; Galaburda, M. Activated Carbon from Agricultural Wastes for Adsorption of Organic Pollutants. Molecules 2020, 25, 5105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haerifar, M.; Azizian, S. Fractal-Like Adsorption Kinetics at the Solid/Solution Interface. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 13111–13119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczewski, A.W. Analysis of Kinetic Langmuir Model. Part I: Integrated Kinetic Langmuir Equation (IKL): A New Complete Analytical Solution of the Langmuir Rate Equation. Langmuir 2010, 26, 15229–15238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachnio, M.; Zienkiewicz-Strzalka, M.; Derylo-Marczewska, A.; Nosach, L.V.; Voronin, E.F. Chitosan– silica composites for adsorption application in the treatment of water and wastewater from anionic dyes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachnio, M.; Zienkiewicz-Strzalka, M.; Kutkowska, J.; Derylo-Marczewska, A. Nanosilver–Biopolymer–Silica Composites: Preparation, and Structural and Adsorption Analysis with Evaluation of Antimicrobial Properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Carbon Sample | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copolymer 1 (silica template synthesis) | PE10500 | PE9400 | PE10500 | PE9400 | PE10500 |

| Expander 2 (silica template synthesis) | - | TMB | TMB | TMB | TMB |

| Taging 3 [°C] | 70 | 70 | 70 | 90 | 90 |

| SBET 4 [m2/g] | 431 | 625 | 459 | 669 | 698 |

| Sext 5 [m2/g] | 4 | 21 | 5 | 15 | 10 |

| Vt 6 [cm3/g] | 0.30 | 0.67 | 0.37 | 1.15 | 0.98 |

| Vp 7 [cm3/g] | 0.29 | 0.59 | 0.34 | 1.07 | 0.93 |

| Vp/Vt 8 | 0.95 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.95 |

| DBJH ads 9 [nm] | 3.10 | 4.48 | 3.42 | 6.92 | 5.41 |

| DBJH des 10 [nm] | 3.01 | 4.06 | 3.29 | 6.36 | 5.04 |

| Carbon | Ton 1 [°C] | Tmax 1 [°C] | ΔH 1 [J/g] | Ton 2 [°C] | Tmax 2 [°C] | ΔH 2 [J/g] | Ton 3 [°C] | Tmax 3 [°C] | ΔH 3 [J/g] | DBJH ads [nm] | DBJH des [nm] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C2 | - | - | - | 1.4 | 2.5 | 0.21 | 54 | 90 | 291 | 3.10 | 3.01 |

| C3 | −33 | −20 | 3 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 0.16 | 62 | 99 | 378 | 4.48 | 4.06 |

| C4 | −43 | −28 | 2 | −1.9 | 0.5 | 18 | 66 | 102 | 517 | 3.42 | 3.29 |

| C5 | −22 | −9 | 24 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.70 | 66 | 97 | 538 | 6.92 | 6.36 |

| C6 | −38 | −17 | 13 | - | - | - | 69 | 102 | 597 | 5.41 | 5.04 |

| System/Isotherm | am [mmol/g] | m | n | log K [L/mmol] | R2 | SD(a) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MB (C2)/GL | 0.38 | 0.15 | 0.57 | 1.61 | 0.992 | 7.97 × 10−3 |

| MB (C3)/GL | 0.52 | 0.12 | 0.96 | 1.54 | 0.979 | 2.11 × 10−2 |

| MB (C4)/GL | 0.39 | 0.12 | 0.55 | 1.64 | 0.975 | 1.15 × 10−2 |

| MB (C5)/GL | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.36 | 1.32 | 0.982 | 1.37 × 10−2 |

| MB (C5)/L | 0.45 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3.00 | −0.524 | 1.10 × 10−1 |

| MB (C6)/GL | 0.55 | 0.10 | 0.70 | 1.36 | 0.911 | 4.37 × 10−2 |

| BB (C5)/GL | 0.38 | 0.22 | 0.55 | 1.63 | 0.988 | 1.19 × 10−2 |

| BB (C5)/L | 0.32 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 0.790 | 4.43 × 10−2 |

| RB (C5)/GL | 0.18 | 0.98 | 0.87 | 2.85 | 0.984 | 6.21 × 10−3 |

| RB (C5)/L | 0.17 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.81 | 0.984 | 5.88 × 10−3 |

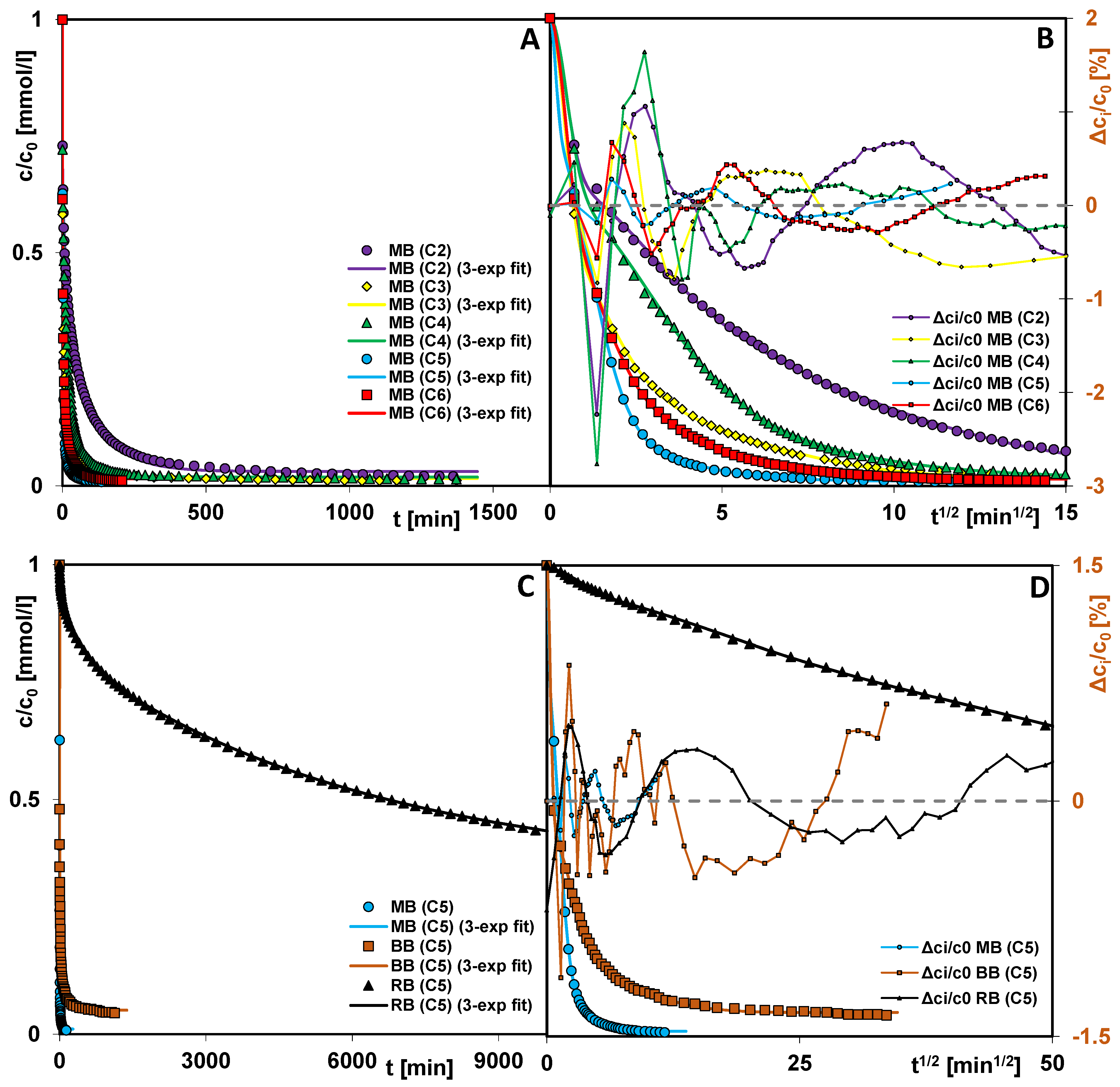

| System | Fit | f2/p | log k 1 | t0.5 [min] | ueq | SD (c/c0) [%] | 1 − R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MB (C2) | 3-exp | - | −1.02 | 7.21 | 0.97 | 0.66 | 1.01 × 10−3 |

| f-FOE | 0/0.38 | −1.30 | 7.52 | 1.00 | 1.18 | 3.52 × 10−3 | |

| IDM | - | −3.77 | 7.80 | 0.85 | 1.86 | 8.69 × 10−3 | |

| PDM | - | - | 9.02 | 0.96 | 2.81 | 1.95 × 10−2 | |

| MB (C3) | 3-exp | - | −0.05 | 0.78 | 0.98 | 0.45 | 6.51 × 10−4 |

| f-FOE | 0/0.35 | −0.39 | 0.86 | 0.99 | 0.32 | 3.56 × 10−4 | |

| IDM | - | −3.30 | 0.99 | 0.91 | 0.40 | 5.63 × 10−4 | |

| PDM | - | - | 0.86 | 0.99 | 0.33 | 3.63 × 10−4 | |

| MB (C4) | 3-exp | - | −0.76 | 3.96 | 0.98 | 0.52 | 7.47 × 10−4 |

| f-FOE | 0/0.47 | −0.95 | 4.12 | 0.99 | 1.11 | 3.73 × 10−3 | |

| IDM | - | −2.88 | 4.11 | 0.66 | 1.08 | 3.48 × 10−3 | |

| PDM | - | - | 3.90 | 0.98 | 0.43 | 5.38 × 10−4 | |

| MB (C5) | 3-exp | - | −0.22 | 1.14 | 0.99 | 0.15 | 4.37 × 10−5 |

| f-FOE | 0/0.59 | −0.27 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.71 | 1.22 × 10−3 | |

| IDM | - | −1.76 | 0.97 | 0.33 | 0.97 | 2.25 × 10−3 | |

| PDM | - | - | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 2.12 × 10−3 | |

| MB (C6) | 3-exp | - | −0.12 | 0.92 | 0.99 | 0.27 | 2.47 × 10−4 |

| f-FOE | 0/0.43 | −0.36 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.37 | 4.92 × 10−4 | |

| IDM | - | −2.62 | 0.94 | 0.79 | 0.41 | 6.13 × 10−4 | |

| PDM | - | - | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.28 | 2.75 × 10−4 | |

| BB (C5) | 3-exp | - | 0.27 | 0.37 | 0.95 | 0.40 | 5.30 × 10−4 |

| f-MOE | 0.29/0.30 | −0.63 | 0.54 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 3.54 × 10−3 | |

| IDM | - | −7.10 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 2.02 | 1.53 × 10−2 | |

| PDM | - | - | 0.28 | 0.94 | 0.74 | 1.86 × 10−3 | |

| RB (C5) | 3-exp | - | −3.54 | 2401 | 0.66 | 0.23 | 1.37 × 10−4 |

| f-FOE | 0/0.49 | −4.17 | 7039 | 1.00 | 0.37 | 3.85 × 10−4 | |

| IDM | - | −6.09 | 6819 | 0.66 | 0.62 | 1.09 × 10−3 | |

| PDM | - | - | 6845 | 0.99 | 0.35 | 3.20 × 10−4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Blachnio, M.; Zienkiewicz-Strzalka, M.; Derylo-Marczewska, A. Analysis of Physical Processes in Confined Pores of Activated Carbons with Uniform Porosity. Materials 2026, 19, 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010191

Blachnio M, Zienkiewicz-Strzalka M, Derylo-Marczewska A. Analysis of Physical Processes in Confined Pores of Activated Carbons with Uniform Porosity. Materials. 2026; 19(1):191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010191

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlachnio, Magdalena, Malgorzata Zienkiewicz-Strzalka, and Anna Derylo-Marczewska. 2026. "Analysis of Physical Processes in Confined Pores of Activated Carbons with Uniform Porosity" Materials 19, no. 1: 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010191

APA StyleBlachnio, M., Zienkiewicz-Strzalka, M., & Derylo-Marczewska, A. (2026). Analysis of Physical Processes in Confined Pores of Activated Carbons with Uniform Porosity. Materials, 19(1), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010191