3.2.1. Electrochemical and Potentiodynamic Polarization Analysis of the Alloys in H2SO4 Aerated Aqueous Solution

This study employs the Nernst equation to calculate the redox equilibrium potentials (E) of metal oxides/hydroxides proceeding through the electrochemical reactions as summarized in

Table 3 at different pH values. The redox equilibrium potentials of corresponding reactions are expressed in Equation (1) or Equation (2):

In these equations,

m denotes the number of moles of OH

− or H

+,

n represents the number of moles of electrons (e

−) involved in the redox process,

E0 is the standard redox equilibrium potential [

26,

27], and 0.197 V corresponds to the potential difference between the Ag/AgCl reference electrode used in this study and the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE).

By incorporating the solubility product constants (K

sp) of metal oxides and hydroxides, the possible composition of passive films formed during potentiodynamic polarization tests can be effectively predicted. The K

sp values of various metal oxides/hydroxides are summarized in

Table 4 [

28,

29], and these values play a critical role in evaluating the corrosion resistance of alloys [

24,

30]. Within electrochemical corrosion mechanisms, K

sp provides a basis for determining the formation and stability of oxides or hydroxides, thereby enabling the assessment of their passivation capability. In general, a lower K

sp indicates reduced solubility, lower ionic release, and a greater tendency to form a stable and compact passive film on the metal surface, which effectively blocks corrosive media and suppresses further metal dissolution. Conversely, a higher K

sp corresponds to higher solubility, hindering the formation of a durable protective layer and resulting in diminished passivation performance. Therefore, K

sp serves as a key parameter for predicting passive film stability and assessing the corrosion resistance behavior of alloys.

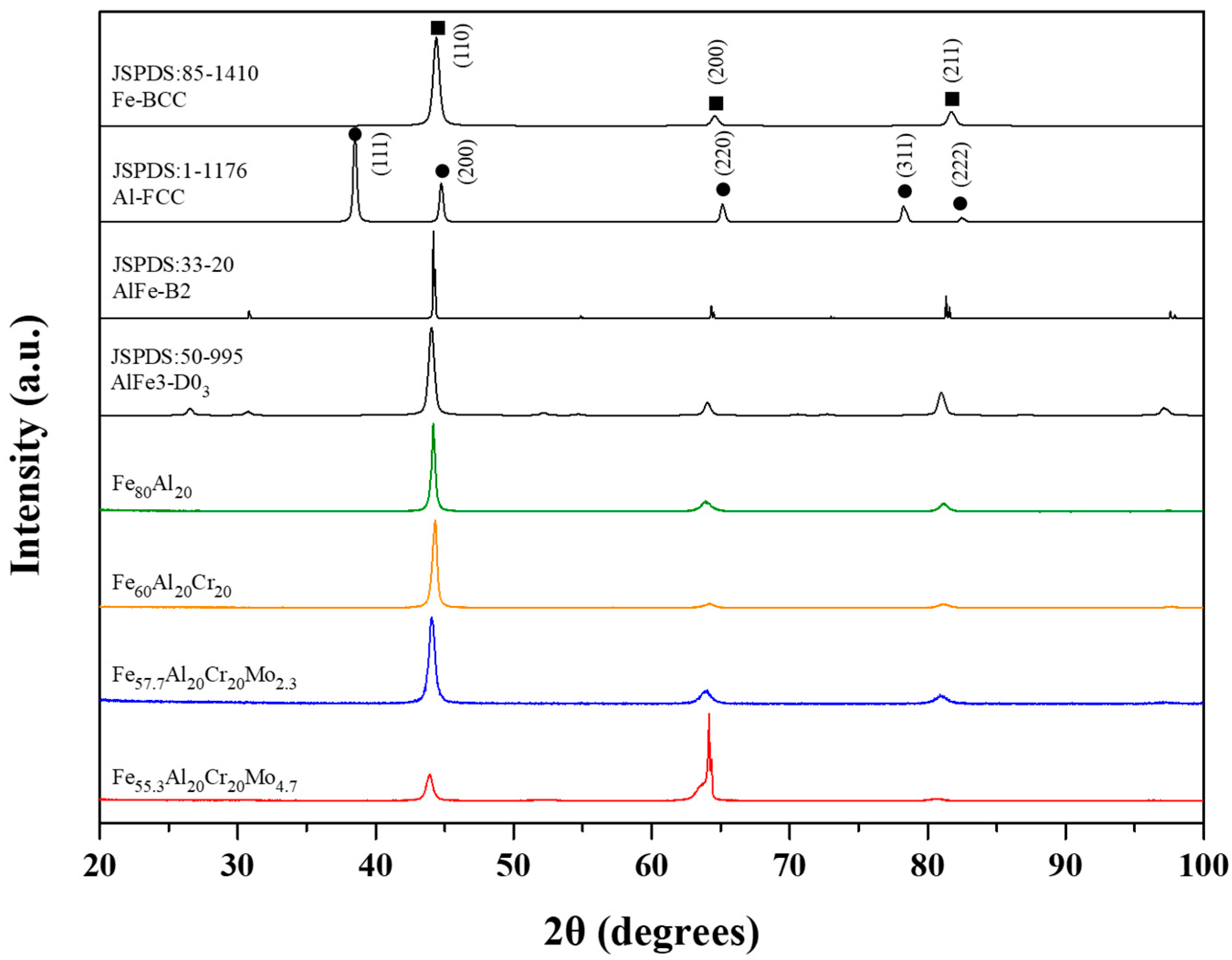

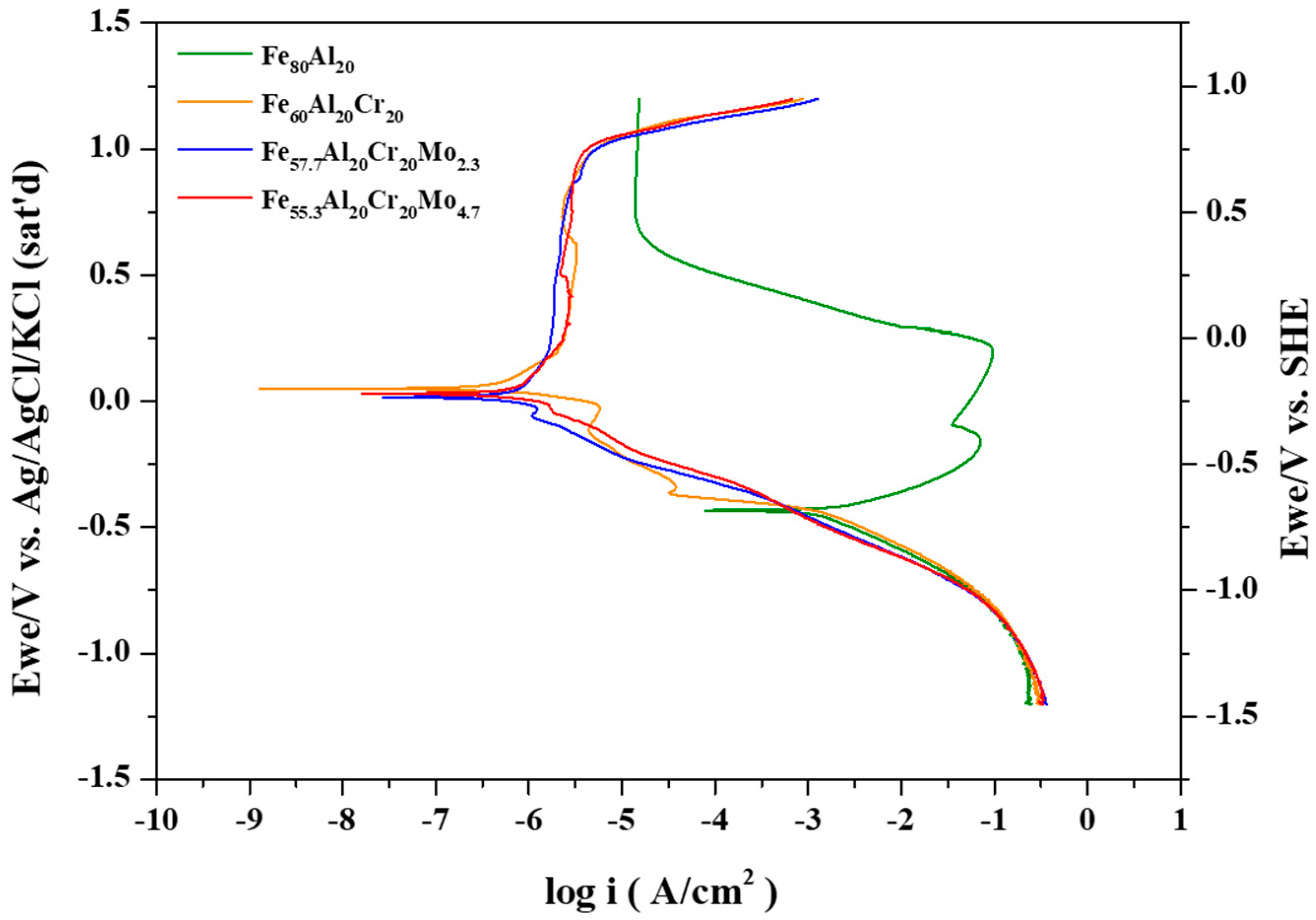

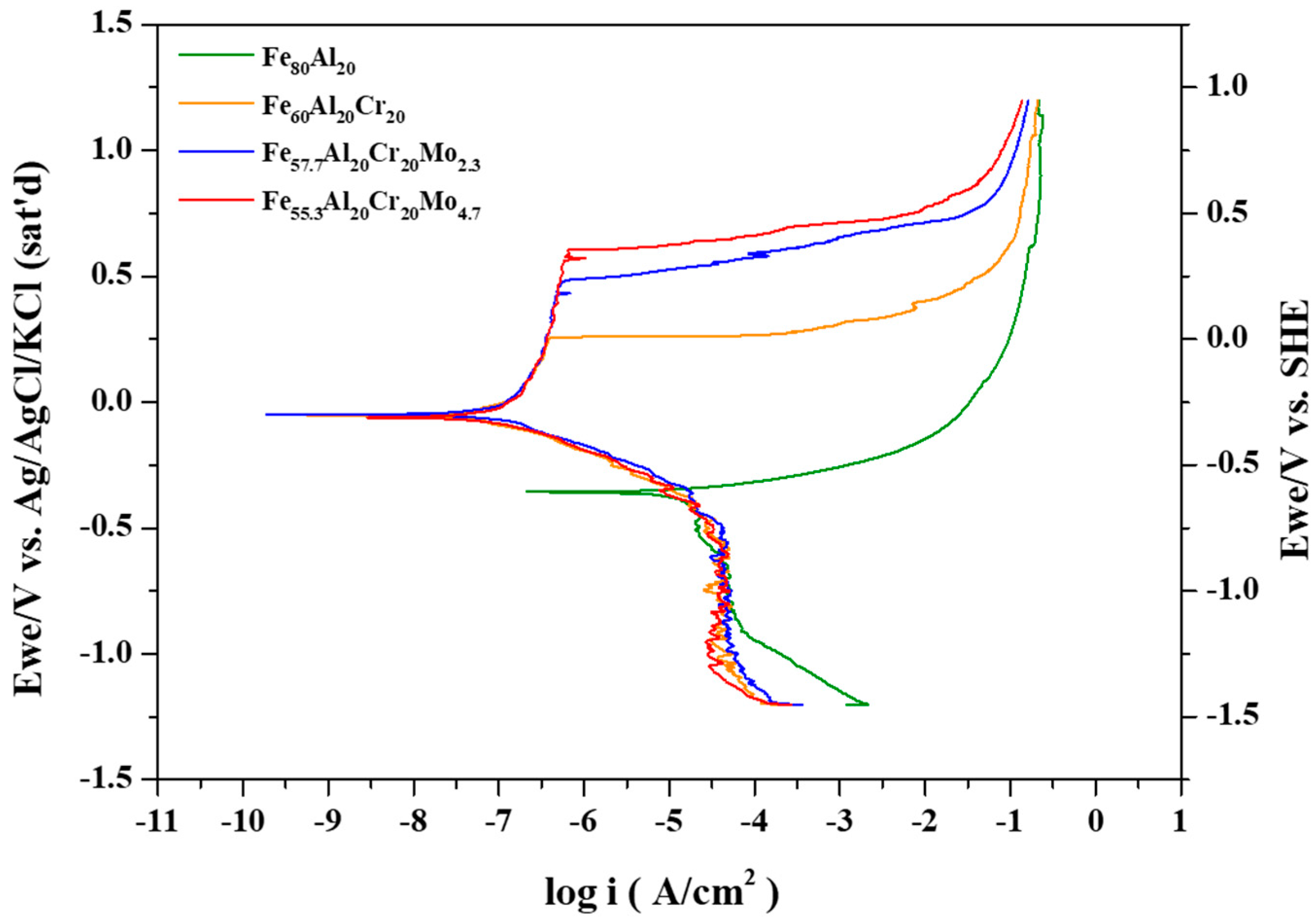

The representative potentiodynamic polarization curves of the Fe

80Al

20, Fe

60Al

20Cr

20, Fe

57.7Al

20Cr

20Mo

2.3, and Fe

55.3Al

20Cr

20Mo

4.7 alloys in oxygenated 0.5 M H

2SO

4 solution are presented in

Figure 2. The corresponding electrochemical parameters, including the open-circuit potential after 30 min of immersion (E

open), corrosion potential (E

corr), corrosion current density (i

corr), passive current density (i

pass), passivation potential (E

trans), and critical current density (i

crit), are summarized in

Table 5 The polarization behavior of these alloys can be rationalized by considering the redox potentials (E) of the constituent metallic elements and the solubility products (K

sp) of their hydroxides, as reported in previous studies [

24,

30].

For the Fe

80Al

20 alloy, the standard electrode potential (E

0) of the electrochemical reaction from Al to Al

3+ is −1.859 V (Ag/AgCl); at higher potentials, aluminum preferentially forms Al

2O

3 and Al(OH)

3, as listed in

Table 3 (Reactions 3 and 4). Although Al(OH)

3 exhibits a relatively low solubility product constant (K

sp = 3 × 10

−34), in sulfuric acid aqueous solution at pH = 0.47, a substantial amount of Al ions (approaching 10

6 as calculated from K

sp and pH) remains dissolved in the solution. On the other hand, the E

0 of the electrochemical reaction from Fe to Fe

2+ is −0.64 V; therefore, iron is more susceptible to preferential dissolution into the electrolyte during the initial stage of corrosion, due to the relatively high solubility product constant of (K

sp = 2 × 10

−15) Fe(OH)

2, which becomes dominant at the potential increasing to −0.064 V by Reaction (8), finally leading to the greater i

crit of 70,300 μA/cm

2 and i

pass of 64,294 μA/cm

2. When the potential is further increased to 0.043 V, Reaction (10) becomes the prevailing reaction pathway; in other words, Fe(OH)

2 is further oxidized to Fe(OH)

3. Owing to the extremely low solubility product constant of Fe(OH)

3 (K

sp = 6 × 10

−38), Fe(OH)

3 progressively precipitates on the alloy surface, promoting the formation of a denser and more protective passive film. The establishment of this passive film effectively suppresses further metal dissolution, resulting in a substantial reduction in the i

pass reduced from 64,294 to 14.5 μA/cm

2 and ultimately leading to the development of a stable passive state.

In the Fe

60Al

20Cr

20 alloy, the addition of Cr promotes the formation of Cr(OH)

3 at approximately −0.697 V, much lower than −0.064 V in Reaction (8), as described by Reaction (5) in

Table 3. Given the lower K

sp (7 × 10

−31) of Cr(OH)

3 than that (2 × 10

−15) of Fe(OH)

2, Cr(OH)

3 readily forms and remains stable on the alloy surface, contributing to the formation of a compact and protective passive film, leading to a reduced i

cirt from 70,300 to 12,080 μA/cm

2 and reduced i

pass from 14.5 to 2.43 μA/cm

2. When Mo is added to the alloy, such as Fe

57.7Al

20Cr

20Mo

2.3 and Fe

55.3Al

20Cr

20Mo

4.7, it is sequentially oxidized at −0.377 V and 0.355 V to form MoO

2 and MoO

3, respectively. These oxides, MoO

2 and MoO

3, further reinforce the structure of the Cr-rich passive film, rendering the existing Cr(OH)

3 layer more compact and robust, finally exhibiting a much reduced i

cirt from 12,080 to 78.8 μA/cm

2. These alloys maintain stable passive films and demonstrate excellent corrosion resistance at potentials up to 1.0 V.

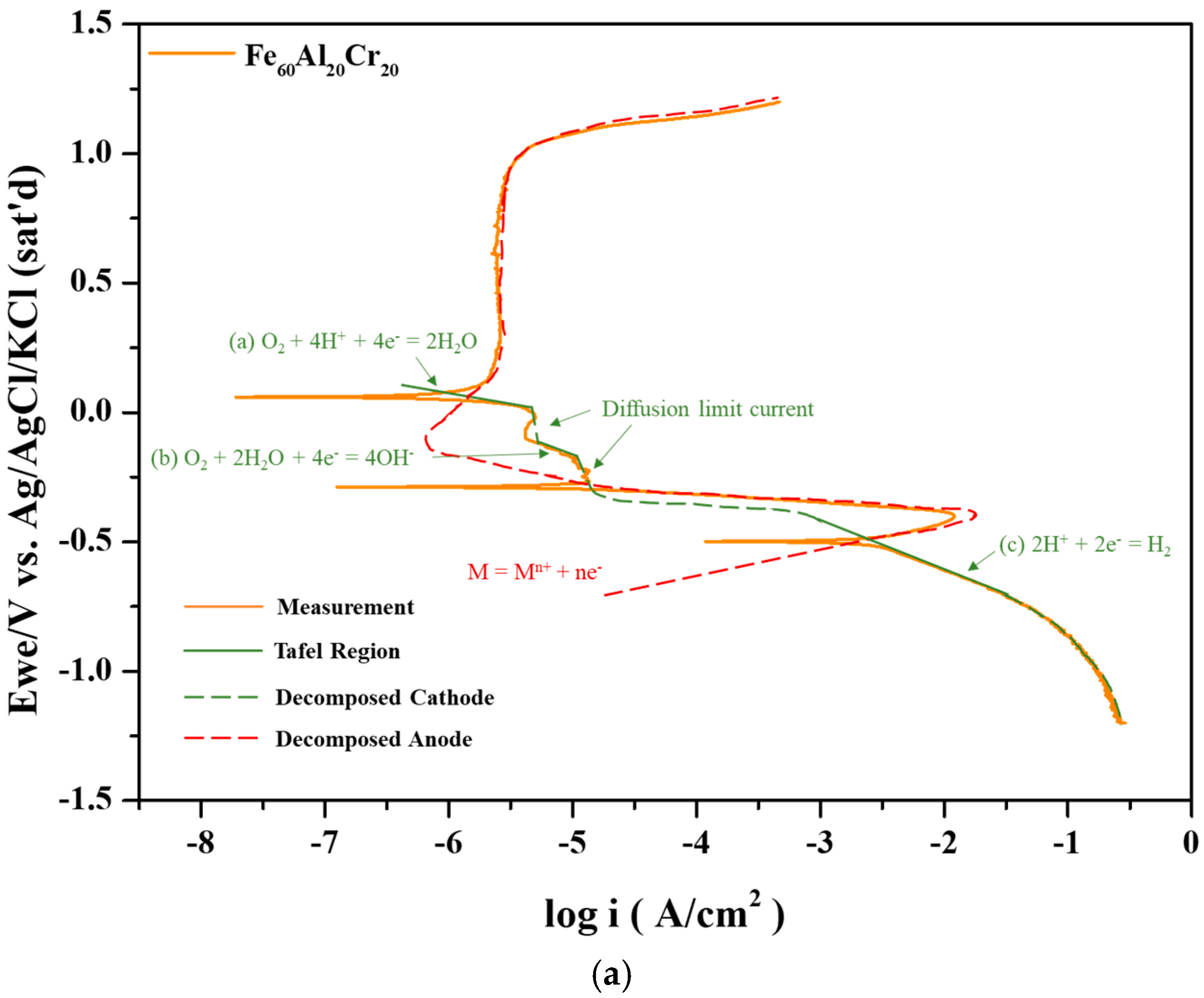

In the Fe–Al system, the polarization curve exhibits only a single corrosion potential since both the critical current density and passive current density are relatively high. However, upon the addition of Cr, the critical current density decreases significantly, and the passivation occurs rapidly, resulting in the intersection with the cathodic polarization curve of O

2 diffusion limit current density in Reaction (b) and revealing the second corrosion potential. Finally, the anodic passivation curve intersects with the cathodic Reaction (a) at the third corrosion potential, as shown in

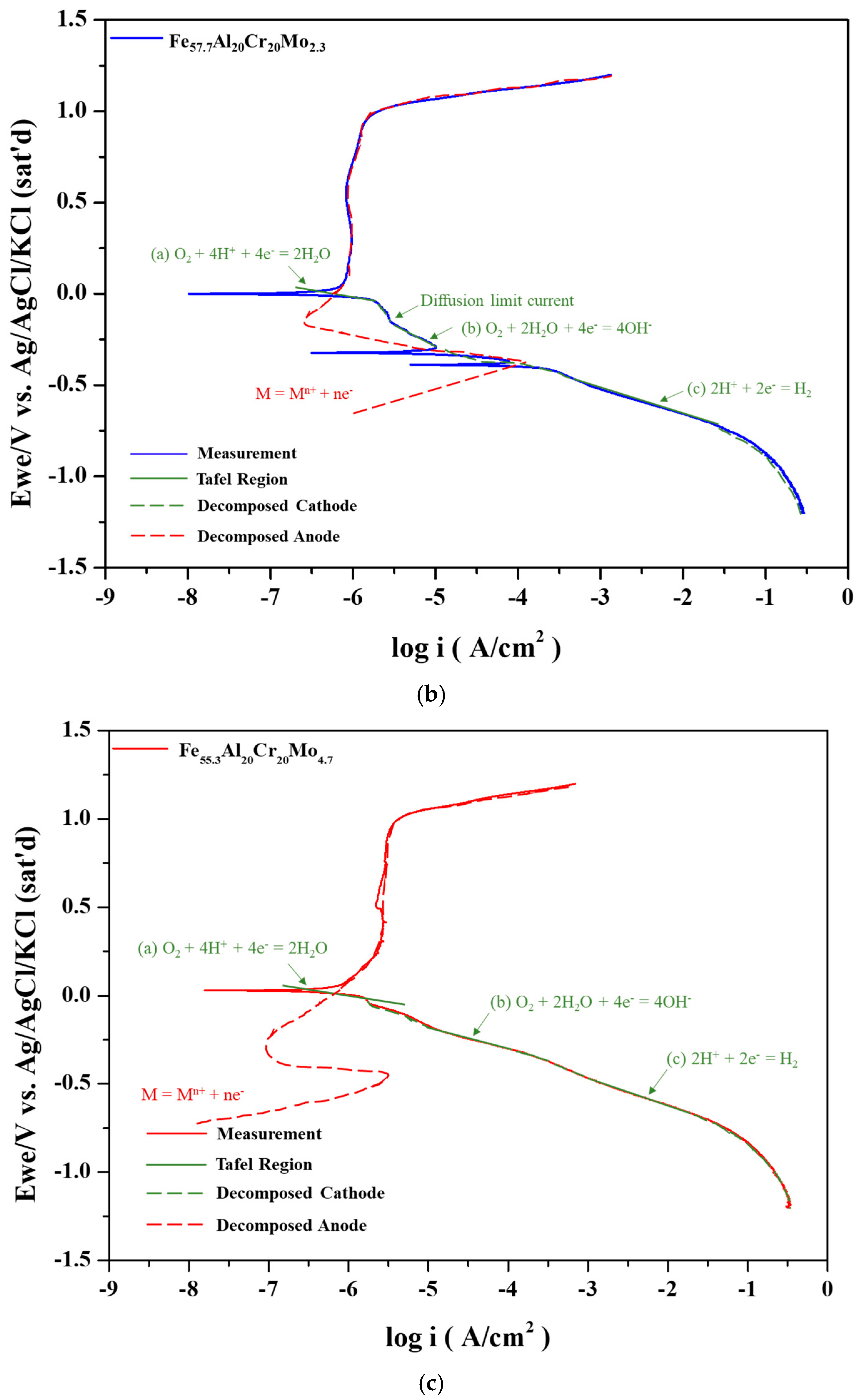

Figure 3a. Under these conditions, the anodic polarization curve intersects the cathodic polarization curve three times, corresponding to three corrosion potentials. With the addition of a small amount of Mo, the critical current density further decreases, yet the anodic and cathodic curves still produce three intersections, as shown in

Figure 3b, similar to

Figure 3a. The first corrosion potential lies between the Tafel regions of Reactions (b) and (c); the second corrosion potential is located by the intersection of the anodic curve with the Tafel region of Reaction (b); and the third corrosion potential arises from the intersection between the passive current region and the Tafel region of Reaction (a).

For the Fe

55.3Al

20Cr

20Mo

4.7 alloy shown in

Figure 3c, an even lower critical current density is observed. In this case, the anodic polarization curve no longer intersects Reactions (b) or (c) at a lower potential and instead intersects only with the Tafel region of Reaction (a) at a higher potential, resulting in a single corrosion potential. The three corrosion potentials were also described in a previous report of 304 stainless steel and CoCrFeNi high entropy alloys [

24].