High-Capacity Adsorption of a Cationic Dye Using Alkali-Activated Geopolymers Derived from Agricultural Residues

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Geopolymer Synthesis

2.3. Characterization

2.4. Adsorption Experiments

2.4.1. Preparation of Methylene Blue Solutions

2.4.2. Batch Adsorption Tests

2.5. Adsorption Calculations and Kinetic Modeling

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Adsorbent Characterization

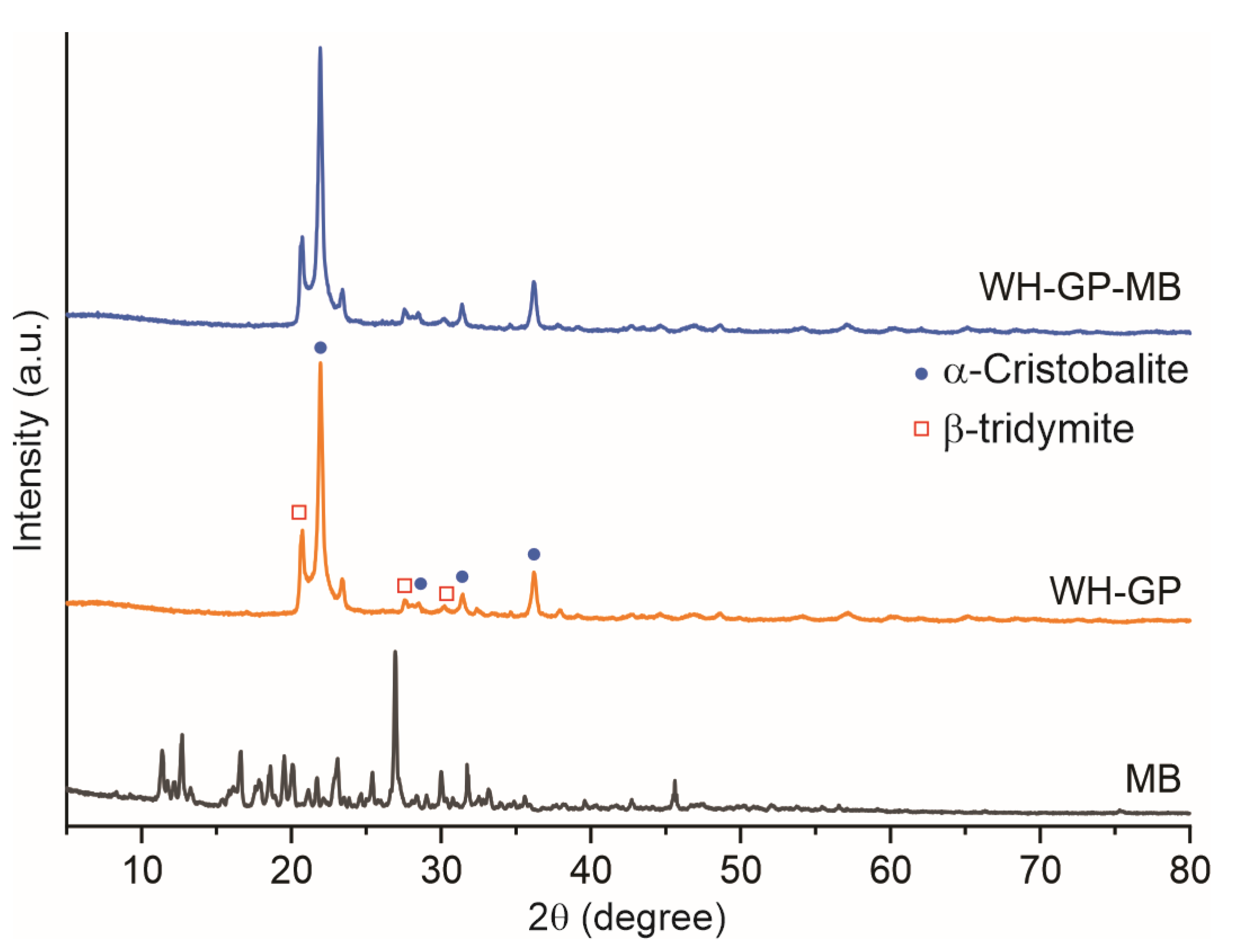

3.1.1. Structural Analysis and Morphological (XRD and SEM)

3.1.2. Functional Group Analysis

3.2. Batch Adsorption Performance

3.3. Adsorption Kinetics

- Rapid initial electrostatic attraction: Under the alkaline conditions generated by NaOH/Na2SiO3, the WH-GP surface develops a high density of negative charges (=Si–O−) due to the deprotonation of oxygen groups. This promotes the rapid initial capture of MB+ ions, primarily driven by electrostatic attraction. This step is often accompanied by ion exchange, in which Na+ ions associated with the WH-GP surface are exchanged for MB+ ions as MB+ approaches. The Cl− counterion of the dye does not participate in the anchoring and remains in solution.

- Slower chemisorption step: In a second, slower stage crucial for the kinetics, the dye establishes stronger, specific interactions with the surface (e.g., hydrogen bonds with neighboring groups or coordinate bonding), giving this final stage a chemisorption character.

3.4. Comparative Adsorption Capacity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maged, A.; El-Fattah, H.A.; Kamel, R.M.; Kharbish, S.; Elgarahy, A.M. A Comprehensive Review on Sustainable Clay-Based Geopolymers for Wastewater Treatment: Circular Economy and Future Outlook. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Tohamy, R.; Ali, S.S.; Li, F.; Okasha, K.M.; Mahmoud, Y.A.-G.; Elsamahy, T.; Jiao, H.; Fu, Y.; Sun, J. A Critical Review on the Treatment of Dye-Containing Wastewater: Ecotoxicological and Health Concerns of Textile Dyes and Possible Remediation Approaches for Environmental Safety. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 231, 113160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Chang, Q.; Li, C. Rapid Removal of Methylene Blue and Nickel Ions and Adsorption/Desorption Mechanism Based on Geopolymer Adsorbent. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun. 2021, 45, 100551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Saeed, K.; Zekker, I.; Zhang, B.; Hendi, A.H.; Ahmad, A.; Ahmad, S.; Zada, N.; Ahmad, H.; Shah, L.A.; et al. Review on Methylene Blue: Its Properties, Uses, Toxicity and Photodegradation. Water 2022, 14, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettahiri, Y.; Bouna, L.; Hanna, J.V.; Benlhachemi, A.; Pilsworth, H.L.; Bouddouch, A.; Bakiz, B. Pyrophyllite Clay-Derived Porous Geopolymers for Removal of Methylene Blue from Aqueous Solutions. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 296, 127281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novais, R.M.; Ascensão, G.; Tobaldi, D.M.; Seabra, M.P.; Labrincha, J.A. Biomass Fly Ash Geopolymer Monoliths for Effective Methylene Blue Removal from Wastewaters. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 783–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chang, M.; Li, C.; Lu, X.; Wang, Q. 3D Printed Geopolymer Adsorption Sieve for Removal of Methylene Blue and Adsorption Mechanism. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 648, 129235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Yang, L.; Rao, F.; Zheng, Y.; Song, Z. Adsorption Behavior and Mechanism of MB, Pb(II) and Cu(II) on Porous Geopolymers. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 11455–11466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, W.; Ye, J. Adsorption Properties and Mechanisms of Geopolymers and Their Composites in Different Water Environments: A Comprehensive Review. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 62, 105393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Elakneswaran, Y.; Islam, C.R.; Provis, J.L.; Sato, T. Adsorption Behaviour of Simulant Radionuclide Cations and Anions in Metakaolin-Based Geopolymer. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 429, 128373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikova, L.A.; Bogdanov, D.S.; Belchinskaya, L.I.; Kolousek, D.; Doushova, B.; Lhotka, M.; Petukhova, G.A. Adsorption of Formaldehyde from Aqueous Solutions Using Metakaolin-Based Geopolymer Sorbents. Prot. Met. Phys. Chem. Surf. 2019, 55, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Yang, L.; Rao, F.; Zhang, K.; Qin, Z.; Song, Z.; Na, Z. Behaviors and Mechanisms of Adsorption of MB and Cr(VI) by Geopolymer Microspheres under Single and Binary Systems. Molecules 2024, 29, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo-Fierro, X.; Gaona, S.; Ramón, J.; Valarezo, E. Porous Geopolymer/ZnTiO3/TiO2 Composite for Adsorption and Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue Dye. Polymers 2023, 15, 2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Su, L.; Pei, Y. Characterization and Adsorption Performance of Waste-Based Porous Open-Cell Geopolymer with One-Pot Preparation. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 12153–12162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Meng, Y.; Qiu, X.; Zhou, F.; Wang, H.; Zhou, S.; Yan, C. Novel Porous Phosphoric Acid-Based Geopolymer Foams for Adsorption of Pb(II), Cd(II) and Ni(II) Mixtures: Behavior and Mechanism. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 7030–7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Hamid, E.M.; Aly, H.M.; El Naggar, K.A.M. Synthesis of Nanogeopolymer Adsorbent and Its Application and Reusability in the Removal of Methylene Blue from Wastewater Using Response Surface Methodology (RSM). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alahmad, J.; BiBi, A.; Al-Ghouti, M.A. Application of TiO2-Loaded Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer in Adsorption of Methylene Blue from Water: Waste-to-Value Approach. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 25, 101138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Alouani, M.; Alehyen, S.; El Achouri, M.; Taibi, M. Preparation, Characterization, and Application of Metakaolin-Based Geopolymer for Removal of Methylene Blue from Aqueous Solution. J. Chem. 2019, 2019, 4212901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Sufian, S.; Hassan, F.; Shamsuddin, R.; Farooq, M. Phosphoric Acid Based Geopolymer Foam-Activated Carbon Composite for Methylene Blue Adsorption: Isotherm, Kinetics, Thermodynamics, and Machine Learning Studies. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 1989–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, N.P.F.; Olhero, S.M.; Labrincha, J.A.; Novais, R.M. 3D-Printed Red Mud/Metakaolin-Based Geopolymers as Water Pollutant Sorbents of Methylene Blue. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 383, 135315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseev, A.A.; Alikina, Y.A.; Golubeva, O.Y. Effect of Particles Morphology on the Mechanical Properties of Aluminosilicate-Based Geopolymers. ACS Appl. Eng. Mater. 2025, 3, 3008–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewuyi, Y.G. Recent Advances in Fly-Ash-Based Geopolymers: Potential on the Utilization for Sustainable Environmental Remediation. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 15532–15542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Van Deventer, J.S.J. Effect of Source Materials on Geopolymerization. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2003, 42, 1698–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Jie, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, G. Synthesis and Characterization of Red Mud and Rice Husk Ash-Based Geopolymer Composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2013, 37, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provis, J.L. Alkali-Activated Materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 114, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somna, K.; Jaturapitakkul, C.; Kajitvichyanukul, P.; Chindaprasirt, P. NaOH-Activated Ground Fly Ash Geopolymer Cured at Ambient Temperature. Fuel 2011, 90, 2118–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Escobar, C.A.; Conejo-Dávila, A.S.; Vega-Rios, A.; Zaragoza-Contreras, E.A.; Farias-Mancilla, J.R. Study of Geopolymers Obtained from Wheat Husk Native to Northern Mexico. Materials 2023, 16, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxson, P.; Fernández-Jiménez, A.; Provis, J.L.; Lukey, G.C.; Palomo, A.; Van Deventer, J.S.J. Geopolymer Technology: The Current State of the Art. J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 42, 2917–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, L.; Jena, S.K.; Rath, S.S.; Misra, P.K. Heavy Metal Removal from Water by Adsorption Using a Low-Cost Geopolymer. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 24284–24298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Z.; Tang, M.; Zhang, M.; Du, C.; Cui, H.-L.; Wei, D. Transformation and Dehydration Kinetics of Methylene Blue Hydrates Detected by Terahertz Time-Domain Spectroscopy. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 41667–41674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dong, H.; Zhao, X.; Wang, K.; Gao, X. Utilisation of Bayer Red Mud for High-Performance Geopolymer: Competitive Roles of Different Activators. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chindaprasirt, P.; Rattanasak, U.; Taebuanhuad, S. Role of Microwave Radiation in Curing the Fly Ash Geopolymer. Adv. Powder Technol. 2013, 24, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshghabadi, F.; Javanbakht, V. Preparation of Porous Metakaolin-Based Geopolymer Foam as an Efficient Adsorbent for Dye Removal from Aqueous Solution. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1295, 136639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barışçı, S.; Turkay, O.; Dimoglo, A. Review on Greywater Treatment and Dye Removal from Aqueous Solution by Ferrate (VI). In ACS Symposium Series; Sharma, V.K., Doong, R., Kim, H., Varma, R.S., Dionysiou, D.D., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Volume 1238, pp. 349–409. ISBN 978-0-8412-3187-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hmoudah, M.; Paparo, R.; De Luca, M.; Fortunato, M.E.; Tammaro, O.; Esposito, S.; Tesser, R.; Di Serio, M.; Ferone, C.; Roviello, G.; et al. Adsorption of Methylene Blue on Metakaolin-Based Geopolymers: A Kinetic and Thermodynamic Investigation. ChemEngineering 2025, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Ul Haq, E.; Ahmed, F.; Asif Rafiq, M.; Hameed Awan, G.; Zain-ul-Abdein, M. Effect of Microwave Curing on the Construction Properties of Natural Soil Based Geopolymer Foam. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 230, 117074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elewa, K.; Tawfic, A.F.; Tarek, M.; Al-Sagheer, N.A.; Nagy, N.M. Removal of Methylene Blue from Synthetic Industrial Wastewater by Using Geopolymer Prepared from Partially Dealuminated Metakaolin. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satpathy, S.R.; Bhattacharyya, S. Adsorptive Dye Removal Using Clay-Based Geopolymer: Effect of Activation Conditions on Geopolymerization and Removal Efficiency. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2025, 319, 118348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Ma, X.; Zou, J.; Zhao, M.; Chen, D.; Xu, D.; Yuan, B. Preparation and Adsorption Properties of Microsphere Geopolymers Derived from Calcium Carbide Slag and Fly Ash. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candamano, S.; Coppola, G.; Mazza, A.; Caicho Caranqui, J.I.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Chakraborty, S.; Alexis, F.; Algieri, C. Batch and Fixed Bed Adsorption of Methylene Blue onto Foamed Metakaolin-Based Geopolymer: A Preliminary Investigation. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2023, 197, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, M.; El-Fawal, E.M.; El Naggar, A.M.A.; El-Zahhar, A.A.; Alghamdi, M.M. Sustainable Geopolymer Synthesized from Industrial Waste as Innovative Adsorbents for Efficient Methylene Blue Removal from Wastewater. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 49, 113968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzioğlu, P.; Yucel, S.; Rabagah, T.M.; Özçimen, D. Characterization of Wheat Hull and Wheat Hull Ash as a Potential Source of SiO2. BioResources 2013, 8, 4406–4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, S.K.; Ashish, D.K.; Rudžionis, Ž. A Review on Sustainable Use of Agricultural Straw and Husk Biomass Ashes: Transitioning towards Low Carbon Economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Z. Geopolymeric Adsorbents from Fly Ash for Dye Removal from Aqueous Solution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2006, 300, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, K.D.; Thu, T.T.; Tran, A.T.H.; Le, O.T.K.; Sagadevan, S.; Mohd Kaus, N.H. Effect of Red Mud and Rice Husk Ash-Based Geopolymer Composites on the Adsorption of Methylene Blue Dye in Aqueous Solution for Wastewater Treatment. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 41258–41272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Method (w AM (mg)) | k2 × 10−3 (g/(h mg)) | qe,cal (mg/g) | qe,exp (mg/g) | Removal (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSO (35) | 3.8893 | 303.30 | 293.23 | 75.76 |

| PSO (50) | 3.9200 | 238.09 | 228.54 | 85.20 |

| Adsorbent | Precursor/Source | Time | Qmax (mg/g) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geopolymer (WH-GP) | Wheat Husk Ash | 8 h | 293.23 | This study |

| Phosphoric-acid geopolymer + activated carbon (ACP) | Phosphoric-acid geopolymer foam + activated carbon composite | 240 min | 204.08 | [19] |

| TiO2-modified fly-ash geopolymer | Fly ash + TiO2 nanoparticles | - | 103.19 | [17] |

| Nanogeopolymer | Fired-brick/burnt clay brick waste | ~163 min | 80.65 | [16] |

| Fly ash geopolymer | Coal Fly Ash | 75 h | 18.3 | [44] |

| Metakaolin-Based Geopolymer | Kaolin | 3 h | 43.48 | [18] |

| Red Mud and Rice Husk Ash-Based Geopolymer Composites | Red Mud and Rice Husk Ash | 3 h | 3.9 | [45] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hernández-Escobar, C.A.; Mares-García, A.S.; Orozco-Alvarado, M.A.; Vega-Rios, A.; Piñón-Balderrama, C.I.; Estrada-Monje, A.; Zaragoza-Contreras, E.A. High-Capacity Adsorption of a Cationic Dye Using Alkali-Activated Geopolymers Derived from Agricultural Residues. Materials 2026, 19, 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010177

Hernández-Escobar CA, Mares-García AS, Orozco-Alvarado MA, Vega-Rios A, Piñón-Balderrama CI, Estrada-Monje A, Zaragoza-Contreras EA. High-Capacity Adsorption of a Cationic Dye Using Alkali-Activated Geopolymers Derived from Agricultural Residues. Materials. 2026; 19(1):177. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010177

Chicago/Turabian StyleHernández-Escobar, Claudia Alejandra, América Susana Mares-García, Miguel Alonso Orozco-Alvarado, Alejandro Vega-Rios, Claudia Ivone Piñón-Balderrama, Anayansi Estrada-Monje, and Erasto Armando Zaragoza-Contreras. 2026. "High-Capacity Adsorption of a Cationic Dye Using Alkali-Activated Geopolymers Derived from Agricultural Residues" Materials 19, no. 1: 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010177

APA StyleHernández-Escobar, C. A., Mares-García, A. S., Orozco-Alvarado, M. A., Vega-Rios, A., Piñón-Balderrama, C. I., Estrada-Monje, A., & Zaragoza-Contreras, E. A. (2026). High-Capacity Adsorption of a Cationic Dye Using Alkali-Activated Geopolymers Derived from Agricultural Residues. Materials, 19(1), 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010177