Laser Deposition of Metal Oxide Structures for Gas Sensor Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

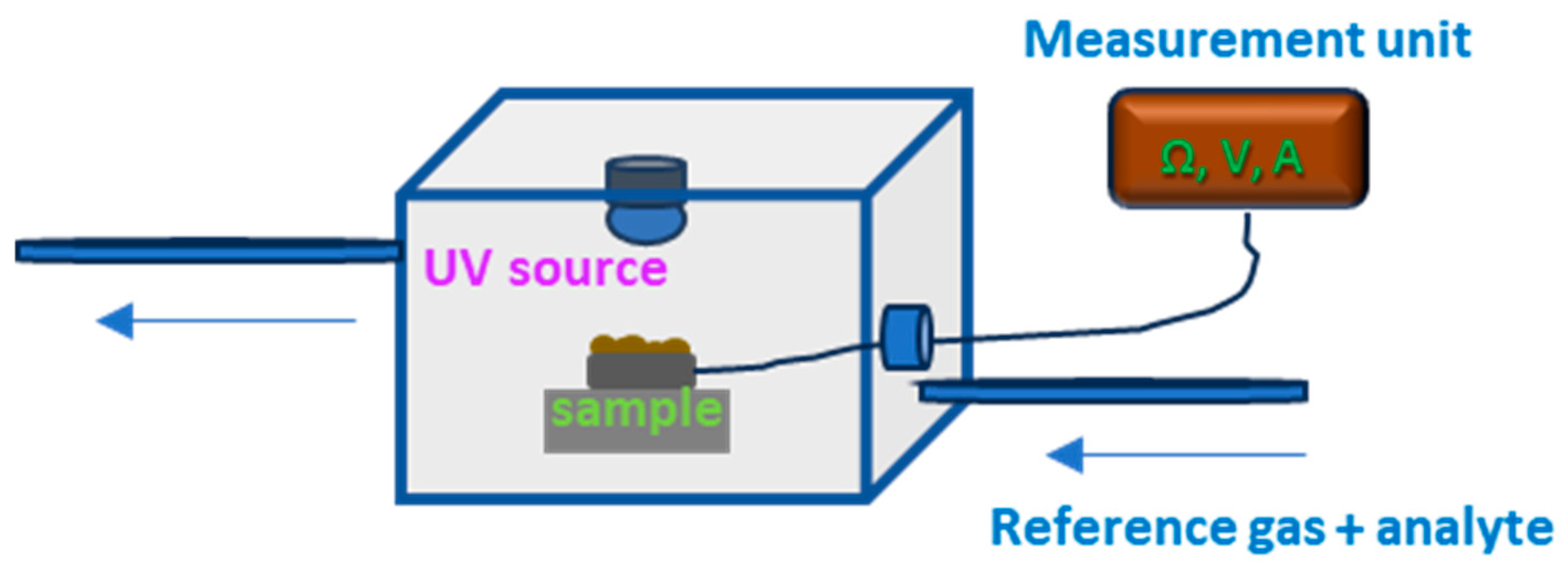

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

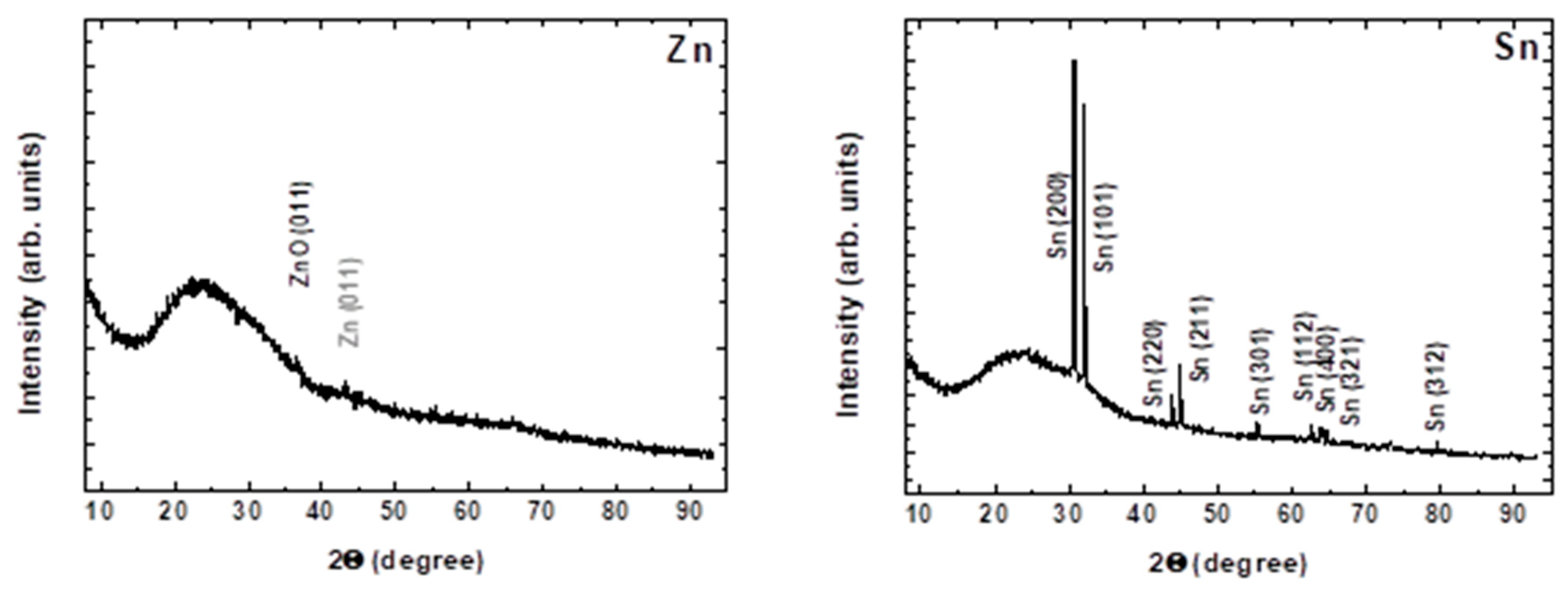

3.1. Laser-Induced Reverse Transfer Using Zn and Sn Targets

3.1.1. Surface Morphology

3.1.2. Composition and Structure of the Deposited Material

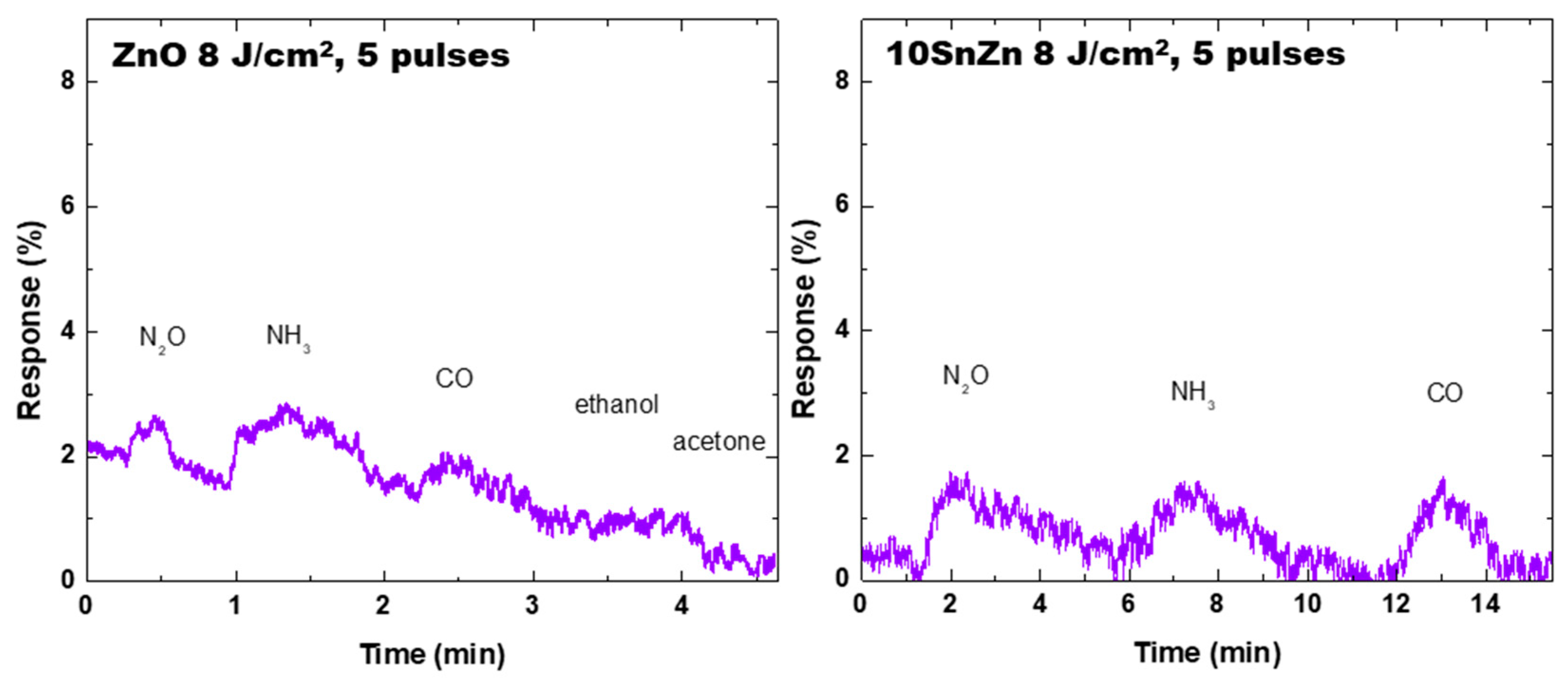

3.2. Laser-Induced Reverse Transfer Using Oxide Targets

3.2.1. Surface Morphology

3.2.2. Composition and Structure of the Deposited Material

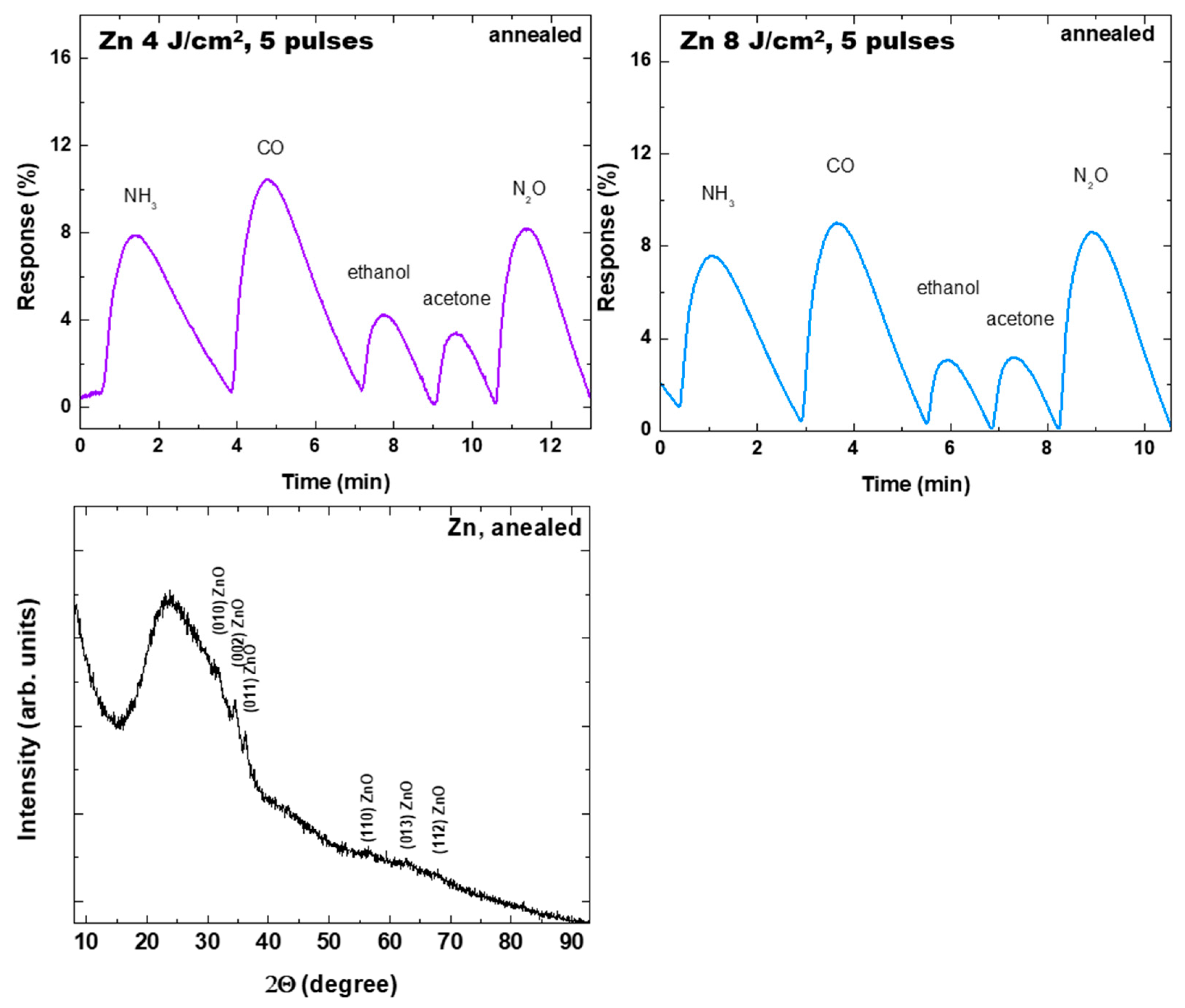

3.3. Resistive Gas Sensor Properties

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiang, K.; Xie, M.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yang, D. Large-Area Nanostructure Fabrication with a 75 nm Half-Pitch Using Deep-UV Flat-Top Laser Interference Lithography. Sensors 2025, 25, 5906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salami, P.; Yousefi, L. Far-field interference nano-lithography for creating arbitrary sub-diffraction patterns. Opt. Laser Technol. 2026, 193, 114168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jency, R.J.; Mazumder, J.T.; Aloshious, A.B.; Jha, R.K. Single electron transistor based charge sensors: Fabrication challenges and opportunities. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 11960–12013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Ryu, K.; Dong, Z.; Hu, Y.; Ke, Y.; Dong, Z.; Long, Y. Micro/nanofabrication of heat management materials for energy-efficient building facades. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2024, 10, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, P.; Verma, J.; Abhinav, V.; Ratnesh, R.K.; Singla, Y.K.; Kumar, V. Advancements in Lithography Techniques and Emerging Molecular Strategies for Nanostructure Fabrication. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shafiq, M.; Liu, M.; Morsi, Y.; Mo, X. Advanced fabrication for electrospun three-dimensional nanofiber aerogels and scaffolds. Bioact. Mater. 2020, 5, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.-Y.; Zhu, R.-Q.; Xia, H.; Liu, Y.-F. Laser micro-nano processing of optoelectronic materials. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2026, 8, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Lin, H.; Zhang, B.; Cao, G.; Chen, F.; Jia, B. Laser-nanofabrication-enabled multidimensional photonic integrated circuits. Photonics Insights 2025, 4, R05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, R.; Li, M.G. Recent Advances in Laser Manufacturing: Multifunctional Integrative Sensing Systems for Human Health and Gas Monitoring. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2407503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naresh, P.K. Laser cutting technique: A literature review. Mat. Today Proc. 2022, 56, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Han, W.; Suleiman, A.A.; Han, S.; Miao, N.; Ling, F.C.-C. Recent Advances on Pulsed Laser Deposition of Large-Scale Thin Films. Small Methods 2024, 8, 2301282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Yan, K.; Zhu, H.; Wang, B.; Zou, B. Laser Micro/Nano-Structuring Pushes Forward Smart Sensing: Opportunities and Challenges. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2211272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleu, Y.; Bourquard, F.; Barnier, V.; Loir, A.-S.; Garrelie, F.; Donnet, C. Towards Room Temperature Phase Transition of W-Doped VO2 Thin Films Deposited by Pulsed Laser Deposition: Thermochromic, Surface, and Structural Analysis. Materials 2023, 16, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, A.; Aziz, M.R.; Gontad, F. Various Configurations for Improving the Efficiency of Metallic and Superconducting Photocathodes Prepared by Pulsed Laser Deposition: A Comparative Review. Materials 2024, 17, 5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paris, G.; Klinkusch, A.; Heidepriem, J.; Tsouka, A.; Zhang, J.; Mende, M.; Mattes, D.S.; Mager, D.; Riegler, H.; Eickelmann, S.; et al. Laser-induced forward transfer of soft material nanolayers with millisecond pulses shows contact-based material deposition. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 508, 144973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveglia, T.; Crimella, D.; Demir, A.G. Laser induced reverse transfer of bulk Cu with a fs-pulsed UV laser for microelectronics applications. Microel. Engin. 2024, 288, 112143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhami, G.; Tan, B.; Venketakrishnan, K. Laser induced reverse transfer of gold thin film using femtosecond laser. Opt. Las. Engin. 2011, 49, 866–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinga, C.-F.; Lia, L.; Young, H.-T. Laser-induced backward transfer of conducting aluminum doped zinc oxide to glass for single-step rapid patterning. J. Mat. Proc. Tech. 2020, 275, 116357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, J.; de Fossard, H.; Gabbani, N.; O’Neill, W.; Daly, R. Material ejection dynamics in direct-writing of low resistivity tracks by laser-induced reverse transfer. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 536, 147924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaie, N.; Kiani, A. Enhancement of bioactivity of glass by deposition of nanofibrous Ti using high intensity laser induced reverse transfer method. Vacuum 2018, 157, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, R.; Ertugrul, M.; Larrea, A.; Navarro, R.; Rico, V.; Yubero, F.; Gonzalez-Elipe, A.R.; de la Fuente, G.F.; Angurel, L.A. Laser-induced scanning transfer deposition of silver electrodes on glass surfaces: A green and scalable technology. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 556, 149673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiko, V.P.; Shakhno, E.A.; Smirnov, V.N.; Miaskovski, A.M.; Nikishin, G.D. Laser–induced film deposition by LIFT: Physical mechanisms and applications. Las. Part. Beams 2006, 24, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, A.I.; Koch, J.; Chichkov, B.N. Laser-induced backward transfer of gold nanodroplets. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 18820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drabczyk, K.; Sobik, P.; Kulesza-Matlak, G.; Jeremiasz, O. Laser-Induced Backward Transfer of Light Reflecting Zinc Patterns on Glass for High Performance Photovoltaic Modules. Materials 2023, 16, 7538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedyalkov, N.; Nikov, R.; Nikov, R.; Dikovska, A.; Stankova, N.; Atanasov, P.; Atanasova, G.; Aleksandrov, L.; Grochowska, K.; Karczewski, J.; et al. Laser-induced gold and silver nanoparticle implantation in glass for fabrication of plasmonic structures with multiple use. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 191, 113361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.; Shukla, A.; Nakamura, D.; Singh, V.; Palani, I.A. Parametric Investigation on Laser-Induced Forward Transfer of ZnO Nanostructure on Flexible PET Sheet for Optoelectronic Application. Microelectron. Eng. 2021, 244–246, 111569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chliara, M.A.; Hatziapostolou, A.; Zergioti, I. Laser-Induced Forward Transfer in Organ-on-Chip Devices. Photonics 2025, 12, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, K.T.; Rocha, L.E.R.; Almeida, J.M.P.; Mendonça, C.R. Direct laser writing of platinum via femtosecond laser-induced forward transfer. Opt. Mater. 2025, 167, 117273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantinou, P.; Vainos, N.A.; Fotakis, C. Microfabrication by UV femtosecond laser ablation of Pt, Cr and indium oxide thin films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1999, 151, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, J.; Lubrani, P.; Li, L. On the selective deposition of tin and tin oxide on various glasses using a high power diode laser. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2001, 137, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Velazquez, A.; Amiaga, J.; Veiko, V.; Khuznakhmetov, R.; Polyakov, D. The peculiarities of ablation and deposition of brass by nanosecond laser pulses at the LIBT-scheme. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 181, 112006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.; Lin, L.; Hu, Y.; Ji, J.; Wu, W.; Li, Z. Defect-enhanced, composition-controlled porous NiOx/TiOy nanoparticles patterns via ultrafast laser-induced backward transfer for highly efficient synergistic ethanol oxidation. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 192, 113822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutar, R.S.; Barkul, R.P.; Patil, M.K. Sunlight assisted photocatalytic degradation of different organic pollutants and simultaneous degradation of cationic and anionic dyes using titanium and zinc based nanocomposites. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 340, 117191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-Y.; Wang, X.-Z.; Liu, F.-J.; Zhang, G.-S.; Song, X.-J.; Tian, J.; Cui, H.-Z. Fabrication of porous Zn2TiO4–ZnO microtubes and analysis of their acetone gas sensing properties. Rare Met. 2020, 40, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dake, L.S.; Baer, D.R.; Zachara, J.M. Auger parameter measurements of zinc compounds relevant to zinc transport in the environment. Surf. Interface Anal. 1989, 14, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gaashani, R.; Radiman, S.; Daud, A.R.; Tabet, N.; Al-Douri, Y. XPS and optical studies of different morphologies of ZnO nanostructures prepared by microwave methods. Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, 2283–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, M.V.; Safonov, A.V. Structural, optical, XPS, and magnetic properties of Sn–O nanoparticles. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 302, 127739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nose, K.; Suzuki, A.Y.; Oda, N.; Kamiko, M.; Mitsuda, Y. Oxidation of SnO to SnO2 thin films in boiling water at atmospheric pressure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 091905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevie, F.A.; Donley, C.L. Introduction to x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2020, 38, 063204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, T. The Development of Instrumentation for Thin-Film X-ray Diffraction. J. Chem. Educ. 2001, 78, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olorunyolemi, T.; Birnboim, A.; Carmel, Y.; Wilson, O.C., Jr.; Lloyd, I.K. Thermal Conductivity of Zinc Oxide: From Green to Sintered State. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2002, 85, 1249–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikov, R.G.; Dikovska, A.O.; Nedyalkov, N.N.; Atanasov, P.A.; Atanasova, G.; Hirsch, D.; Rauschenbach, B. ZnO nanostructures produced by pulsed laser deposition in open air. Appl. Phys. A 2017, 123, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henley, S.J.; Carey, J.D.; Silva, S.R.P. Pulsed-laser-induced nanoscale island formation in thin metal-on-oxide films. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 72, 195408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charpentier, C.; Boukhicha, R.; Prod’hommea, P.; Emeraud, T.; Lerat, J.-F.; Cabarrocas, P.R.; Johnson, E.V. Evolution in morphological, optical, and electronic properties of ZnO:Al thin films undergoing a laser annealing and etching process. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2014, 125, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grønvold, F.; Stølen, S. Heat capacity of solid zinc from 298.15 to 692.68 K and of liquid zinc from 692.68 to 940 K: Thermodynamic function values. Thermochi. Acta 2003, 395, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ready, J.F. Effects of High-Power Laser Radiation; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, W.S.M.; Glantschnig, K.; Ambrosch-Draxl, C. Optical constants and inelastic electron-scattering data for 17 elemental metals. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 2009, 38, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, F.; Haratizadeh, H.; Ahmadi, M. Improving CO2 sensing and p-n conductivity transition under UV light by chemo-resistive sensor based on ZnO nanoparticles. Ceram. Int. B 2024, 50, 1497–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, N.; Bo, R.; Chen, H.; White, T.P.; Fu, L.; Tricoli, A. Structural Engineering of Nano-Grain Boundaries for Low-Voltage UV-Photodetectors with Gigantic Photo- to Dark-Current Ratios. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2016, 4, 1787–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Yao, H.; Shi, X.; Xu, S. Chemoresistive Gas Sensors Based on Noble-Metal-Decorated Metal Oxide Semiconductors for H2 Detection. Materials 2025, 18, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shooshtari, M. Gold-decorated vertically aligned carbon nanofibers for high-performance room-temperature ethanol sensing. Microchim. Acta 2025, 192, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, P.-S.; Kim, K.-W.; Lee, J.-H. NO2 sensing characteristics of ZnO nanorods prepared by hydrothermal method. J. Electroceram. 2006, 17, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Li, Y.; Zeng, W. Hydrothermal synthesis of hierarchical flower-like ZnO nanostructure and its enhanced ethanol gas-sensing properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 427, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, S.; Qu, F.; Gong, S.; Wang, C.; Qiu, L.; Yang, M.; Cheng, W. High performance acetone sensor based on ZnO nanorods modified by Au nanoparticles. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 797, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, B.; Balaguru, J.B.R.; Babu, K.J. Influence of calcination temperature on the growth of electrospun multi-junction ZnO nanowires: A room temperature ammonia sensor. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process 2020, 112, 105006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakarungsee, P.; Srirattanapibul, S.; Issro, C.; Tang, I.-M.; Thongmee, S. High performance Cr doped ZnO by UV for NH3 gas sensor. Sens. Actuators A 2020, 314, 112230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilova, T.; Atanasova, G.; Dikovska, A.O.; Nedyalkov, N.N. The effect of light irradiation on the gas-sensing properties of nanocomposites based on ZnO and Ag nanoparticles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 505, 144625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Gas Type, Operation Temperature | Concentration (ppm) | Response (%) | Response Time (s) | Recovery Time (s) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn, 4 J/cm2, 5 pulses, annealed | NH3 | 30 | 7.5 | 60 | 120 | This work |

| CO | 30 | 9.8 | 36 | 126 | ||

| Ethanol | 30 | 3.4 | 20 | 56 | ||

| Acetone | 30 | 3.3 | 18 | 42 | ||

| N2O, room temperature | 30 | 8.1 | 24 | 78 | ||

| ZnO nanorods | CO, at ×100 °C | Above 50 | - | - | - | [52] |

| ZnO nanoparticles | Ethanol, at 350 °C | 400 | 20.3 (R0/Rg) | 12 | 4 | [53] |

| ZnO nanorods | Acetone, 172, 219 °C | 100 | 12.9 (R0/Rg) | 13 | 29 | [54] |

| ZnO nanowires | NH3, room temperature | 50 | 20 (R0/Rg) | 88 | 65 | [55] |

| ZnO nanoparticles | NH3, room temperature, UV irradiation | 50 | 8 ((R0 − Rg)/R0) × 100 | 270 | 300 | [56] |

| ZnO nanostructure | NH3 | 40 | 52 | 33–36 | 155–196 | [57] |

| CO | 40 | 33 | ||||

| Ethanol | 40 | 36 | ||||

| Acetone | 40 | 54 | ||||

| Room temperature, UV radiation | ((R0 − Rg)/R0) × 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nedyalkov, N.; Dikovska, A.; Dilova, T.; Atanasova, G.; Andreeva, R.; Avdeev, G. Laser Deposition of Metal Oxide Structures for Gas Sensor Applications. Materials 2026, 19, 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010176

Nedyalkov N, Dikovska A, Dilova T, Atanasova G, Andreeva R, Avdeev G. Laser Deposition of Metal Oxide Structures for Gas Sensor Applications. Materials. 2026; 19(1):176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010176

Chicago/Turabian StyleNedyalkov, Nikolay, Anna Dikovska, Tina Dilova, Genoveva Atanasova, Reni Andreeva, and Georgi Avdeev. 2026. "Laser Deposition of Metal Oxide Structures for Gas Sensor Applications" Materials 19, no. 1: 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010176

APA StyleNedyalkov, N., Dikovska, A., Dilova, T., Atanasova, G., Andreeva, R., & Avdeev, G. (2026). Laser Deposition of Metal Oxide Structures for Gas Sensor Applications. Materials, 19(1), 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010176