Enhanced Resistance to Sliding and Erosion Wear in HVAF-Sprayed WC-Based Cermets Featuring a CoCrNiAlTi Binder

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Preparation of Coatings

2.2. Microstructure Characterization

2.3. Micromechanical Properties

2.4. Sliding Wear Testing

2.5. Erosion Wear Testing

3. Results and Discussion

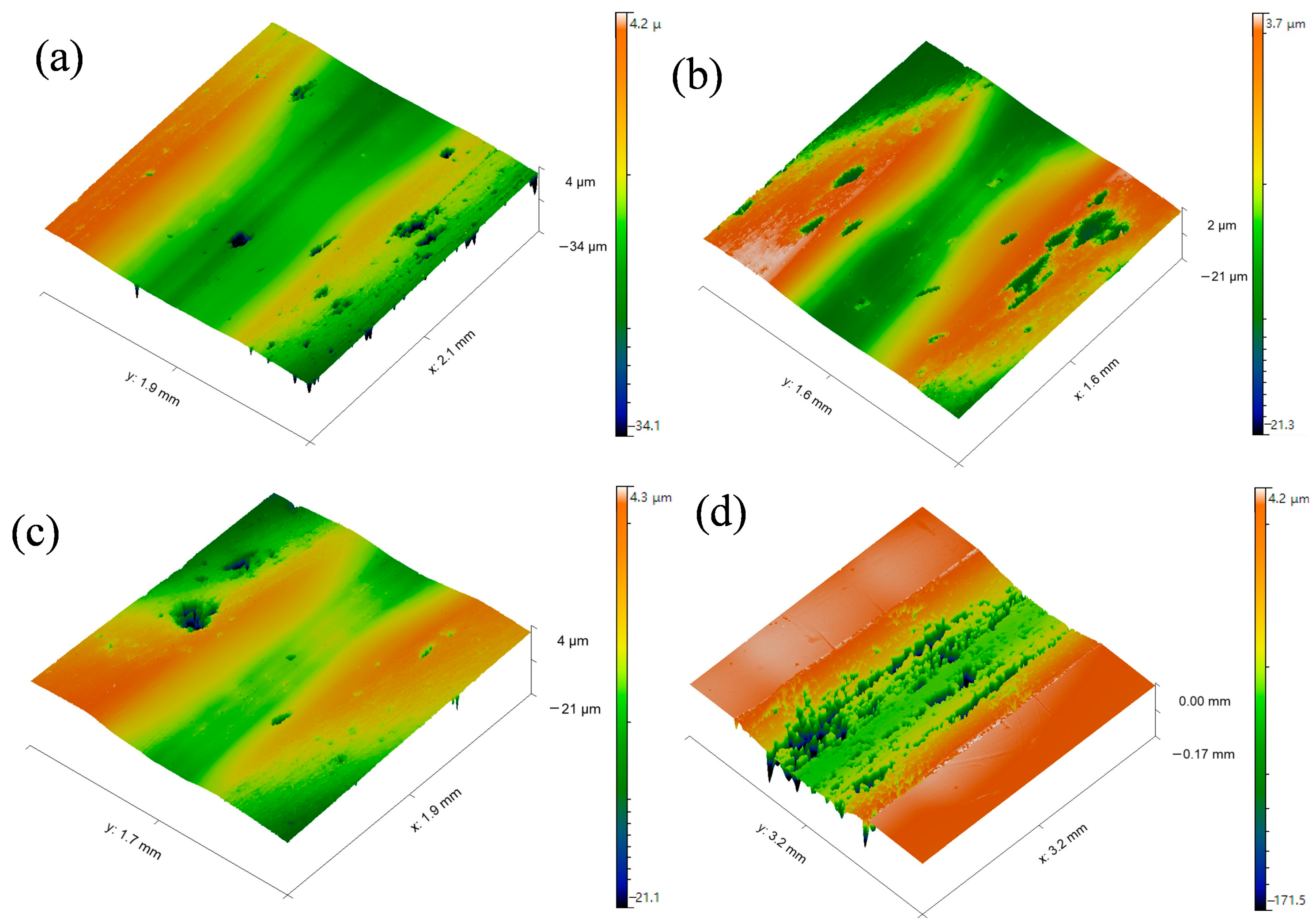

3.1. Microstructure

3.2. Microhardness

3.3. Sliding Wear Performance

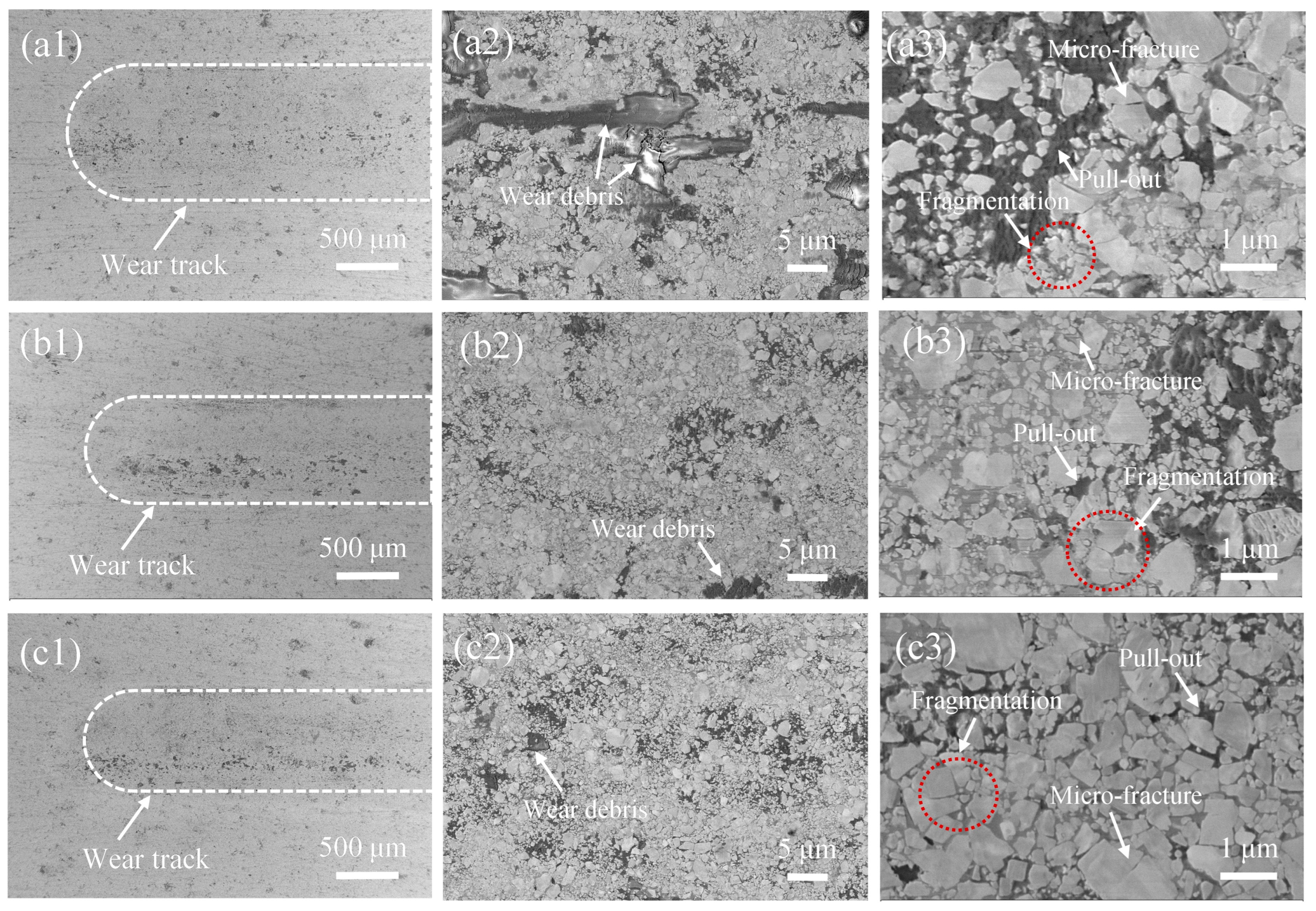

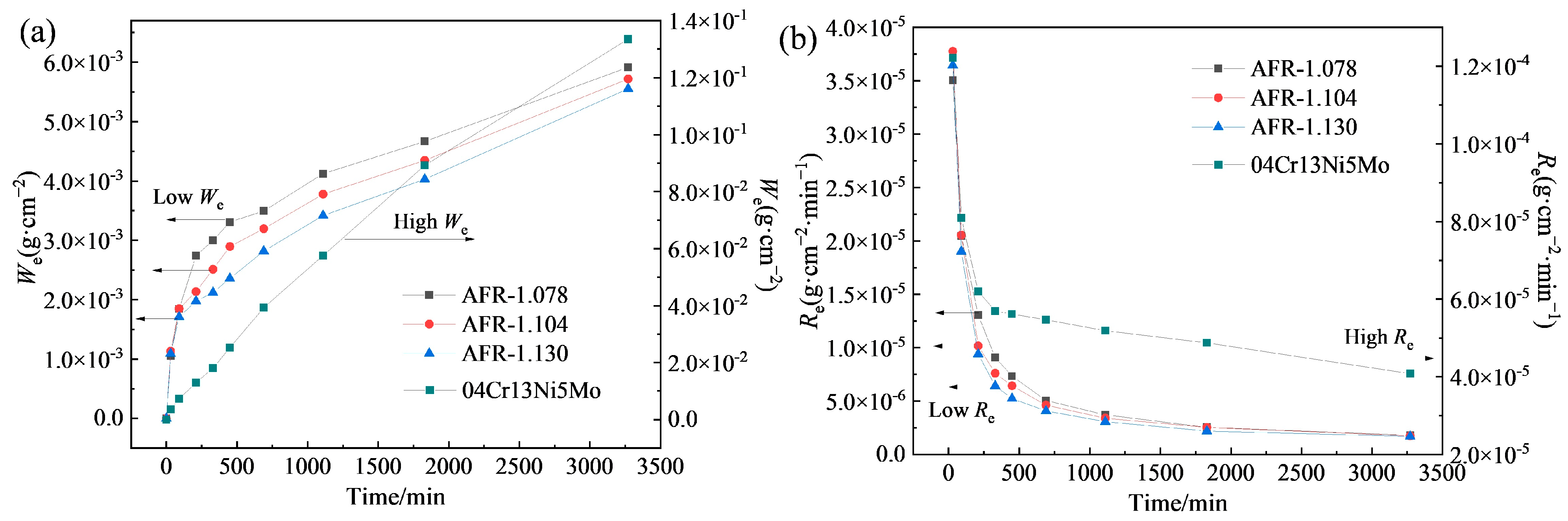

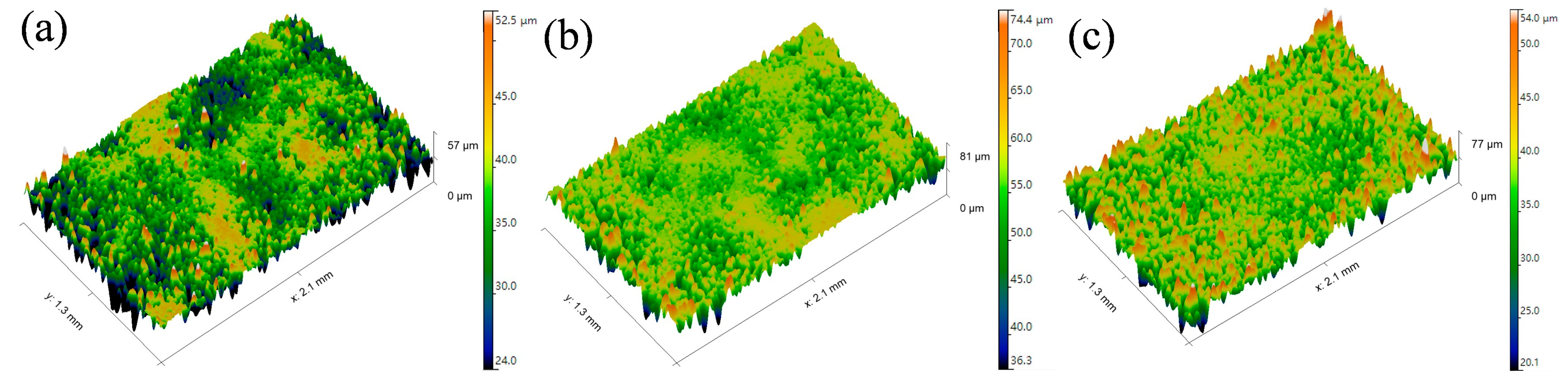

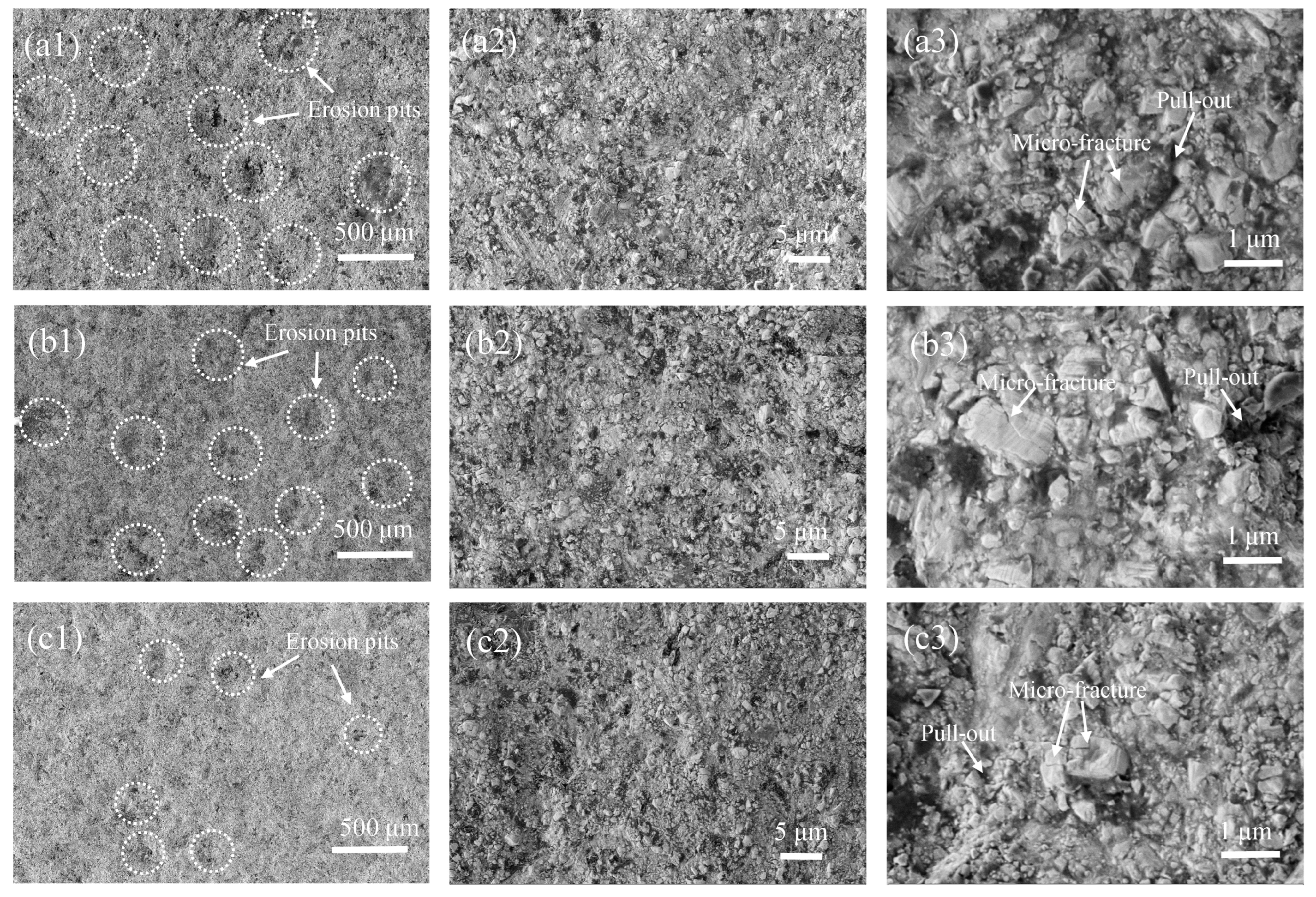

3.4. Erosion Wear Resistance

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- All WC-CoCrNiAlTi coatings consist primarily of WC, (Co, Ni)3W3C, and an FCC binder phase. As the AFR increases, the formation of the (Co, Ni)3W3C phase gradually decreases. Meanwhile, the coating density improves, which is attributed to enhanced particle melting and higher impact velocity, resulting in improved flattening upon deposition.

- (2)

- The average microhardness of the WC-CoCrNiAlTi coatings gradually increases with increasing AFR. The coating sprayed at an AFR of 1.130 exhibits the highest microhardness of 1355.68 HV0.2. This is due to the combined effects of reduced hard and brittle (Co, Ni)3W3C decomposition phases and improved microstructural densification.

- (3)

- Both the friction coefficient and the wear rate of the coatings decrease with increasing AFR. At an AFR of 1.130, the coating demonstrates the lowest friction coefficient (0.6435) and wear rate (1.15 × 10−6 mm3·N−1·m−1). Its wear resistance is 34.85 times higher than that of the 04Cr13Ni5Mo martensitic stainless-steel substrate.

- (4)

- With prolonged slurry erosion time, the cumulative weight loss of the WC-CoCrNiAlTi coatings increases, while the erosion rate decreases. As the AFR increases, the weight loss rate of the coatings gradually declines. The coating produced at an AFR of 1.130 shows the lowest erosion rate (1.70 × 10−6 g·cm−2·min−1), exhibiting slurry erosion resistance 24.04 times greater than that of the 04Cr13Ni5Mo stainless steel substrate.

- (5)

- The slurry erosion mechanism of the WC-CoCrNiAlTi coatings is attributed to the fatigue-induced removal of WC particles under prolonged erosive impact. The AFR significantly influences the slurry erosion resistance by regulating the content of brittle decomposition phases and the density of the coatings.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sangal, S.; Singhal, M.K.; Saini, R.P. Hydro-Abrasive Erosion in Hydro Turbines: A Review. Int. J. Green Energy 2018, 15, 232–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Bhandari, D.; Goyal, K. Slurry Erosion Behaviour of HVOF Sprayed Coatings on Hydro Turbine Steel: A Review. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1033, 012064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, G.A.; Malfatti, C.F.; Schroeder, R.M.; Ferrari, V.Z.; Muller, I.L. WC10Co4Cr Coatings Deposited by HVOF on Martensitic Stainless Steel for Use in Hydraulic Turbines: Resistance to Corrosion and Slurry Erosion. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 377, 124918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maekai, I.A.; Harmain, G.A.; Zehab-ud-Din; Masoodi, J.H. Resistance to Slurry Erosion by WC-10Co-4Cr and Cr3C2−25(Ni20Cr) Coatings Deposited by HVOF Stainless Steel F6NM. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2022, 105, 105830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilardell, A.M.; Cinca, N.; Tarrés, E.; Kobashi, M. Iron Aluminides as an Alternative Binder for Cemented Carbides: A Review and Perspective towards Additive Manufacturing. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 31, 103335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Chen, W.; Liu, J.; Hu, Z.; Qin, C. Chemical Mechanism of Chemical Mechanical Polishing of Tungsten Cobalt Cemented Carbide Inserts. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2020, 88, 105179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, H.; Zhou, J.; Feng, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Analysis of Material Flow among Multiple Phases of Cobalt Industrial Chain Based on a Complex Network. Resour. Policy 2022, 77, 102691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmström, E.; Lizárraga, R.; Linder, D.; Salmasi, A.; Wang, W.; Kaplan, B.; Mao, H.; Larsson, H.; Vitos, L. High Entropy Alloys: Substituting for Cobalt in Cutting Edge Technology. Appl. Mater. Today 2018, 12, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.L.; Tsai, C.W.; Yeh, A.C.; Yeh, J.W. Clarifying the Four Core Effects of High-Entropy Materials. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2024, 8, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-H.; Wu, S.-K.; Liao, B.-S.; Su, C.-H. Selective Leaching and Surface Properties of CoNiCr-Based Medium-/High-Entropy Alloys. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 515, 146044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hering, B.; Gestrich, T.; Steinborn, C.; Vornberger, A.; Pötschke, J. Influence of Alternative Hard and Binder Phase Compositions in Hardmetals on Thermophysical and Mechanical Properties. Metals 2023, 13, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakonechnyi, S.O.; Yurkova, A.I.; Loboda, P.I. WC-Based Cemented Carbide with NiFeCrWMo High-Entropy Alloy Binder as an Alternative to Cobalt. Vacuum 2024, 222, 113052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Yong, J.; Hao, J.; Sun, D.; Cheng, Q.; Jing, H.; Zhou, Z. Tribological Properties and Corrosion Resistance of Stellite 20 Alloy Coating Prepared by HVOF and HVAF. Coatings 2023, 13, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Liu, M.; Wu, C.; Zhou, K.; Song, J. Impingement Resistance of HVAF WC-Based Coatings. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2007, 16, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.K.; Kamaraj, M.; Seetharamu, S.; Anand Kumar, S. A Pragmatic Approach and Quantitative Assessment of Silt Erosion Characteristics of HVOF and HVAF Processed WC-CoCr Coatings and 16Cr5Ni Steel for Hydro Turbine Applications. Mater. Des. 2017, 132, 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- CoBrain Project. (15 March 2023). AMBITION. Available online: https://www.cobrain-project.eu/ambition/ (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Qiang, F.; Zheng, P.; He, P.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Han, P.; Wang, K. Insight into Grain Refinement Mechanisms of WC Cemented Carbide with Al0.5CoCrFeNiTi0.5 Binder. Materials 2024, 17, 4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobzin, K.; Heinemann, H.; Jasutyn, K. Correlation Between Process Parameters and Particle In-Flight Behavior in AC-HVAF. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2023, 32, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Wu, K.; Zhou, J.; Shen, M.G.; Fan, W.; Chen, H.Y.; Kang, Y.X.; Li, B.Q. Flattening and Solidification Behavior of In-Flight Droplets in Plasma Spraying and Micro/Macro-Bonding Mechanisms. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 784, 834–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, S.; Ansbro, J.; Berndt, C.C.; Ang, A.S.M. Carbide Dissolution in WC-17Co Thermal Spray Coatings: Part 1-Project Concept and as-Sprayed Coatings. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 856, 157464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, J.; Voleník, K.; Neufuss, K.; Kolman, B. Vaporization of Components from Alloy Powder Particles in a Plasma Flow. Czechoslov. J. Phys. 2006, 56, B1391–B1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, P.; Zhao, L.; Wu, L.; Li, S. Study on the Process Parameters and Corrosion Resistance of FeCoNiCrAl High Entropy Alloy Coating Prepared by Atmospheric Plasma Spraying. Materials 2025, 18, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, Z.; Wang, A.; Ma, D.; Lou, J.; Qin, C.; Yue, S.; Xie, J. Fracture Toughness Enhancement Mechanism of Multimodal WC-10Co-4Cr Coating Sprayed by HVOF. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2025, 133, 107404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Sun, D.; Fan, Z.; Yu, H.; Meng, H. The Influence of HVAF Powder Feedstock Characteristics on the Sliding Wear Behaviour of WC–NiCr Coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2008, 202, 4893–4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, T.; Wen, M.; Wang, L.L.; Hu, C.Q.; Tian, H.W.; Zheng, W.T. Structures, Mechanical Properties and Thermal Stability of TiN/SiNx Multilayer Coatings Deposited by Magnetron Sputtering. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 486, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Shen, S.; Yang, X.; Song, F.; Dong, W.; Wang, Z.; Wu, M. Study on the Friction and Wear Performance of Laser Cladding WC-TiC/Ni60 Coating on the Working Face of Shield Bobbing Cutter. Opt. Mater. 2024, 148, 114875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, S.X.; Zhang, Z.F. General Relationship between Strength and Hardness. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 529, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, N.; Ramesh, M.R.; Rahman, M.R. Elevated Temperature Wear and Friction Performance of WC-CoCr/Mo and WC-Co/NiCr/Mo Coated Ti-6Al-4V Alloy. Mater. Charact. 2024, 215, 114207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Wu, Y.; Hong, S.; Cheng, J.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, J.; Wei, Z.; Zhu, S. Effects of WC Addition on the Erosion Behavior of High-Velocity Oxygen Fuel Sprayed AlCoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloy Coatings. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 18502–18512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Region | C | W | Co | Cr | Ni | Al | Ti |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal | WC | 50 | 50 | - | - | - | - | - |

| binder | - | - | 60 | 25 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| AFR-1.078 | WC | 50.05 | 46.14 | 2.36 | 1.18 | 0.22 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| binder | - | 29.13 | 45.87 | 18.26 | 3.30 | 1.17 | 2.27 | |

| AFR-1.104 | WC | 49.72 | 45.62 | 2.65 | 0.97 | 0.67 | 0.13 | 0.24 |

| binder | - | 24.76 | 47.35 | 20.94 | 3.51 | 1.23 | 2.21 | |

| AFR-1.130 | WC | 49.91 | 45.94 | 2.58 | 1.17 | 0.33 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| binder | - | 22.20 | 51.54 | 19.03 | 3.65 | 1.30 | 2.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Yu, Y.; Chen, X.; Huo, J.; Zhang, K.; Wei, X.; Zhang, Z.; Hui, X. Enhanced Resistance to Sliding and Erosion Wear in HVAF-Sprayed WC-Based Cermets Featuring a CoCrNiAlTi Binder. Materials 2026, 19, 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010178

Zhang L, Yu Y, Chen X, Huo J, Zhang K, Wei X, Zhang Z, Hui X. Enhanced Resistance to Sliding and Erosion Wear in HVAF-Sprayed WC-Based Cermets Featuring a CoCrNiAlTi Binder. Materials. 2026; 19(1):178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010178

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Lei, Yue Yu, Xiaoming Chen, Jiaxiang Huo, Kai Zhang, Xin Wei, Zhe Zhang, and Xidong Hui. 2026. "Enhanced Resistance to Sliding and Erosion Wear in HVAF-Sprayed WC-Based Cermets Featuring a CoCrNiAlTi Binder" Materials 19, no. 1: 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010178

APA StyleZhang, L., Yu, Y., Chen, X., Huo, J., Zhang, K., Wei, X., Zhang, Z., & Hui, X. (2026). Enhanced Resistance to Sliding and Erosion Wear in HVAF-Sprayed WC-Based Cermets Featuring a CoCrNiAlTi Binder. Materials, 19(1), 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010178