Enhanced Properties of Alumina Cement Adhesive for Large-Tonnage Insulator Under Rapid Curing Regime

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. Testing and Characterisation Methods

2.3.1. Flexural and Compressive Strength

2.3.2. Drying Shrinkage

2.3.3. Dynamic Modulus of Elasticity

2.3.4. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

2.3.5. Low-Field Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (LF-NMR) Testing

2.3.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.3.7. Thermomechanical Performance Testing

3. Results and Discussion

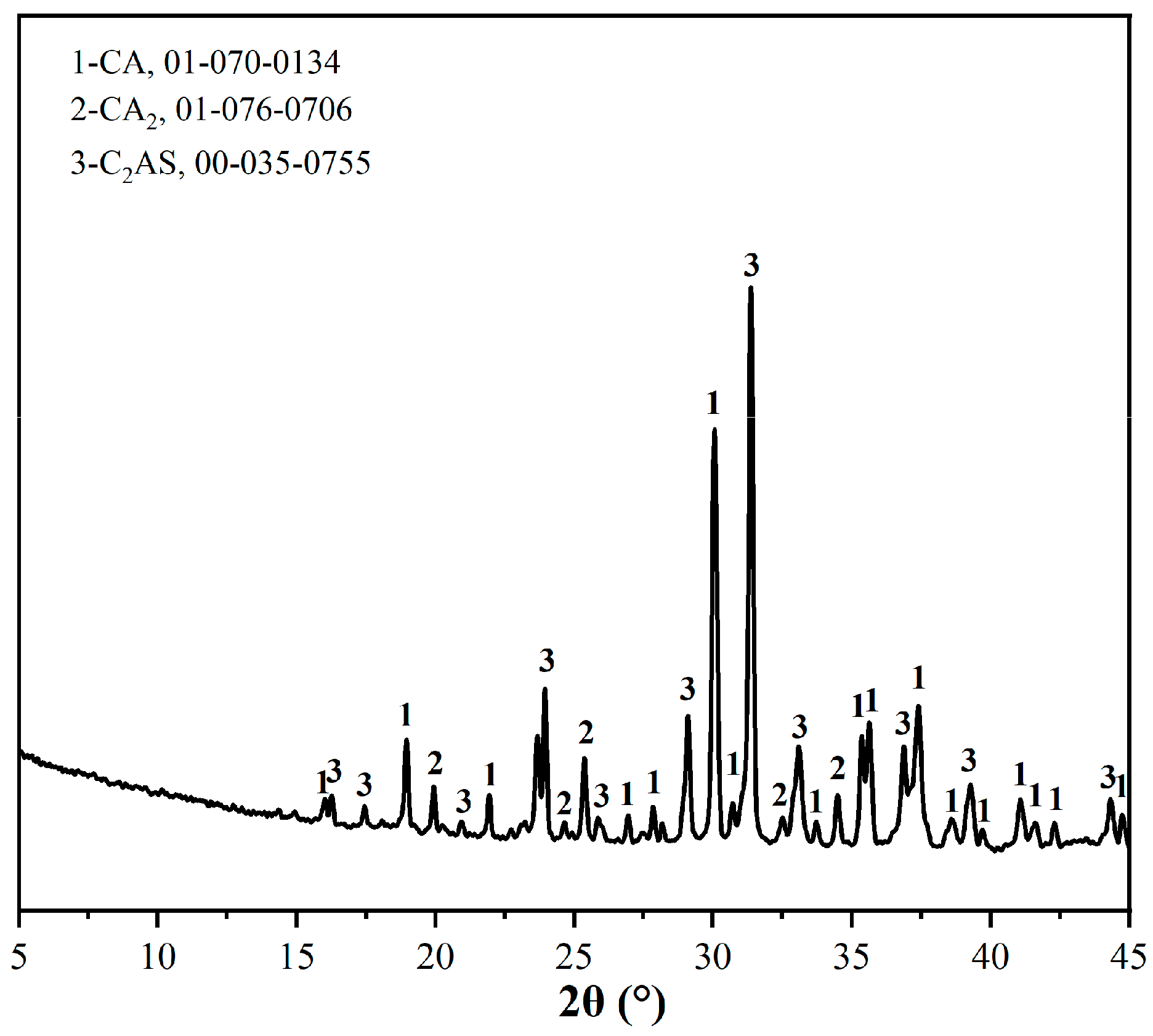

3.1. Effect of Steam Curing Temperature on Hydration Products of Alumina Cement

3.2. Investigation on the Properties of Alumina Cement Adhesive

3.2.1. Flexural and Compressive Strength

3.2.2. Dry Shrinkage Properties

3.2.3. Modulus of Elasticity

3.3. Microstructural Study of Alumina Cement Adhesive

3.3.1. Pore Characteristics

3.3.2. Phase Composition

3.3.3. Microstructure

3.4. Thermomechanical Performance Testing of Alumina Cement-Bonded Porcelain Insulators

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hackam, R. Outdoor HV composite polymeric insulators. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 1999, 6, 557–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, B.; Li, X.; Jing, S.; Gao, Y.; Zeng, D.; Jiang, X. Study on the aging characteristics of a ±500 kV composite dead-end insulator in longtime service. Polymers 2024, 16, 1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell-Watson, S.M.; Sharp, J.H. On the cause of the anomalous setting behaviour with respect to temperature of calcium aluminate cements. Cem. Concr. Res. 1990, 20, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahdini, A.; Momen, G.; Munger, F.; Brettschneider, S.; Fofana, I.; Jafari, R. Performance of a nanotextured superhydrophobic coating developed for high-voltage outdoor porcelain insulators. Colloids Surf. A 2022, 649, 129461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas-Gutierres, L.F.; Maresch, K.; Morais, A.M.; Nunes, M.V.A.; Correa, C.H.; Martins, E.F.; Fontoura, H.C.; Schmidt, M.V.F.; Soares, S.N.; Cardoso, G.; et al. Framework for decision-making in preventive maintenance: Electric field analysis and partial discharge diagnosis of high-voltage insulators. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 233, 110447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Sanyal, S.; Koo, J.-B.; Son, J.-A.; Choi, I.-H.; Yi, J. Analysis of thermal sensitivity by high voltage insulator materials. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 75586–75591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, K.; Qunaynah, S.A.; Wan, S.; Yuan, Z.; Xu, P.; Tang, S. A study on the hydration of calcium aluminate cement pastes containing silica fume using non-contact electrical resistivity measurement. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 8135–8149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Da, Y.; He, T.; Yu, L. The effects of modified interface agents on the bonding characteristics between customized cement adhesive for insulators and aluminum flanges. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Bai, Y.; Cai, Y. Early strength and microstructure of Portland cement mixed with calcium bromide at 5 °C. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 271, 121508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Gu, K.; Chen, B.; Wang, C. Comparison of sawdust bio-composites based on magnesium oxysulfate cement and ordinary portland cement. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 63, 105514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chang, J.; Wang, T.; Zeng, T.; Li, J.; Zhang, J. Effects of phosphogypsum on hydration properties and strength of calcium aluminate cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 347, 128398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Liu, Y.; Lv, J.; Liu, H.; Li, H.; Chen, W. Mechanical and shrinkage properties of engineered cementitious composites with blended use of high-belite sulphoaluminate cement and ordinary Portland cement. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 106, 112551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, A.; Kim, N.; Seo, J.; Farooq, S.Z.; Lee, H.K. Hydration and phase conversion of MgO-modified calcium aluminate cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 369, 130425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Cui, J.; Liu, Y.; Jing, X.; He, B.; Cang, D.; Zhang, L. Enhancing temperature resistance of calcium aluminate cement through carbonated steel slag. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 102, 111956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kula, T.M.; Meiser, M.D.; Tressler, R.E. Curing temperature and humidity effects on the strength of an aluminous cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 1980, 10, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J.; Choo, B.S. Advanced Concrete Technology: Constituent Materials; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2003; ISBN 0-7506-5103-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.A.; Shakouri, M.; Trejo, D.; Vaddey, N.P. Effect of curing temperature and water-to-cement ratio on corrosion of steel in calcium aluminate cement concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 350, 128875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés, P.; Alcocel, E.G.; Chinchón, S.; Andreu, C.G.; Alcaide, J. Effect of curing temperature in some hydration characteristics of calcium aluminate cement compared with those of portland cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 1997, 27, 1343–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacka, M.; Pacewska, B. Effect of structurally different aluminosilicates on early-age hydration of calcium aluminate cement depending on temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 235, 117404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goergens, J.; Manninger, T.; Goetz-Neunhoeffer, F. In-situ XRD study of the temperature-dependent early hydration of calcium aluminate cement in a mix with calcite. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 136, 106160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, T.T.; Weng, Y.; Prasittisopin, L. Effect of steel and polypropylene fiber reinforcement on mitigating conversion effects in calcium aluminate cement at varying curing temperatures. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2025, 16, 103680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Yao, T.; Bao, L.; Chen, J. Effect of carbonated magnesium slag on the performances of aluminate cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 493, 143193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Hu, Z.; Liu, G.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Y. Study of the electrical properties of aluminate cement adhesives for porcelain insulators. Materials 2021, 14, 2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JB/T 4307-2004; Insulator Cementing with Cement Adhesive. CSIC-JB: Beijing, China, 2004.

- GB/T 1001.1-2021; Insulators for Overhead Lines with a Nominal Voltage above 1000 V—Part 1: Ceramic or Glass Insulator Units for A.C. Systems—Definitions, Test Methods and Acceptance Criteria. State Administration for Market Regulation, Standardization Administration: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Erkkilä, A.-L.; Leppänen, T.; Virkajärvi, J.; Parkkonen, J.; Turunen, L.; Tuovinen, T. Quasi-brittle porous material: Simulated effect of stochastic air void structure on compressive strength. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 139, 106255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wang, X.; Mu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, L.; Ye, G. Mechanical property and phase evolution of the hydrates of CAC-bonded alumina castables during drying at 110 °C. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 266, 120962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-H.; Zuo, X.-B.; Zhao, Q.-N.; Chen, B.-Y. The dichotomous role of slag in calcium aluminate cement (CAC) composites: From strength diluent at 20 °C to structural healer at 60 °C. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 49, 114137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.W. Concrete durability syndrome and its prevention. Concrete 1991, 4, 4–8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Ding, S.; Ashour, A.; Yu, F.; Lv, X.; Han, B. Micro-nano scale pore structure and fractal dimension of ultra-high performance cementitious composites modified with nanofillers. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 141, 105129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JB/T 4307-2004; Cement Adhesive for Insulators. China Machinery Industry Federation: Beijing, China, 2004.

- Eren, F.; Keskinateş, M.; Felekoğlu, B.; Felekoğlu, K.T. The role of pre-heating and mineral additive modification on long-term strength development of calcium aluminate cement mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 340, 127720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, H. A novel equivalent laminated model for thermoplastic fabric prepreg and its application in fast hot stamping simulation. Compos. Commun. 2025, 59, 102555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Lin, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Pang, X.; Kong, X. Effects of triethanolamine on autogenous shrinkage and drying shrinkage of cement mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 304, 124620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.; Long, G.; Xie, Y.; Peng, J.; Guo, S. Study on the mitigation of drying shrinkage and crack of limestone powder cement paste and its mechanism. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segawa, M.; Kurihara, R.; Aili, A.; Igarashi, G.; Maruyama, I. Shrinkage reduction mechanism of low ca/si ratio C-a-S-H in cement pastes containing fly ash. Cem. Concr. Res. 2024, 186, 107683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.-F.; Tao, Z.; Pan, Z.; Wuhrer, R. Effect of calcium aluminate cement on geopolymer concrete cured at ambient temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 191, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koudriavtsev, A.B.; Danchev, M.D.; Hunter, G.; Linert, W. Application of 19F NMR relaxometry to the determination of porosity and pore size distribution in hydrated cements and other porous materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 868–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.; Pang, X.; Shi, L.; Song, M.; Yu, B.; Kong, X. Phase compositions and pore structure of phosphate modified calcium aluminate cement hardened pastes with varied dosages of sodium polyphosphate. Cem. Concr. Res. 2024, 184, 107609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, K.T.J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Huang, S.; Cheng, X. The influence of different fine aggregate and cooling regimes on the engineering properties of sulphoaluminate cement mortar after heating. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e01866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, S.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Guan, X. Effects of AH3 and AFt on the hydration–hardening properties of the C4A3Ŝ-CŜ-H2O system. Materials 2023, 16, 6322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | MgO | TiO2 | K2O | Na2O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7.37 | 48.14 | 1.91 | 36.38 | 0.46 | 2.21 | 0.64 | 0.07 |

| Number | Electromechanical Destructive Load/kN | |

|---|---|---|

| 80% Load | 100% Load | |

| 1 | 673.2 (J) | 693.3 (J) |

| 2 | 669.9 (J) | 694.3 (J) |

| 3 | 671.4 (J) | 699.7 (J) |

| 4 | 675.6 (J) | 696.2 (J) |

| 5 | 674.9 (J) | 696.8 (J) |

| 6 | 661.2 (J) | 697.7 (J) |

| 7 | 674.6 (J) | 698.7 (J) |

| 8 | 672.2 (J) | 696.8 (J) |

| Average value X | 671.63 | 696.69 |

| Standard deviation S | 4.63 | 2.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhou, W.; Min, Y.; Zhou, J.; Tian, S. Enhanced Properties of Alumina Cement Adhesive for Large-Tonnage Insulator Under Rapid Curing Regime. Materials 2026, 19, 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010171

Zhou W, Min Y, Zhou J, Tian S. Enhanced Properties of Alumina Cement Adhesive for Large-Tonnage Insulator Under Rapid Curing Regime. Materials. 2026; 19(1):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010171

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Weibing, Yongchao Min, Jun Zhou, and Shouqin Tian. 2026. "Enhanced Properties of Alumina Cement Adhesive for Large-Tonnage Insulator Under Rapid Curing Regime" Materials 19, no. 1: 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010171

APA StyleZhou, W., Min, Y., Zhou, J., & Tian, S. (2026). Enhanced Properties of Alumina Cement Adhesive for Large-Tonnage Insulator Under Rapid Curing Regime. Materials, 19(1), 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010171