Experimental Studies of Strain and Stress Fields in a Granular Medium Under Active Pressure Using DIC and Elasto-Optic Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

Novelty and Contribution of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Digital Image Correlation for Displacement and Strain Fields

2.2. Photoelastic Studies of Granular Materials

2.3. Integration of DIC and Elasto-Optic Methods

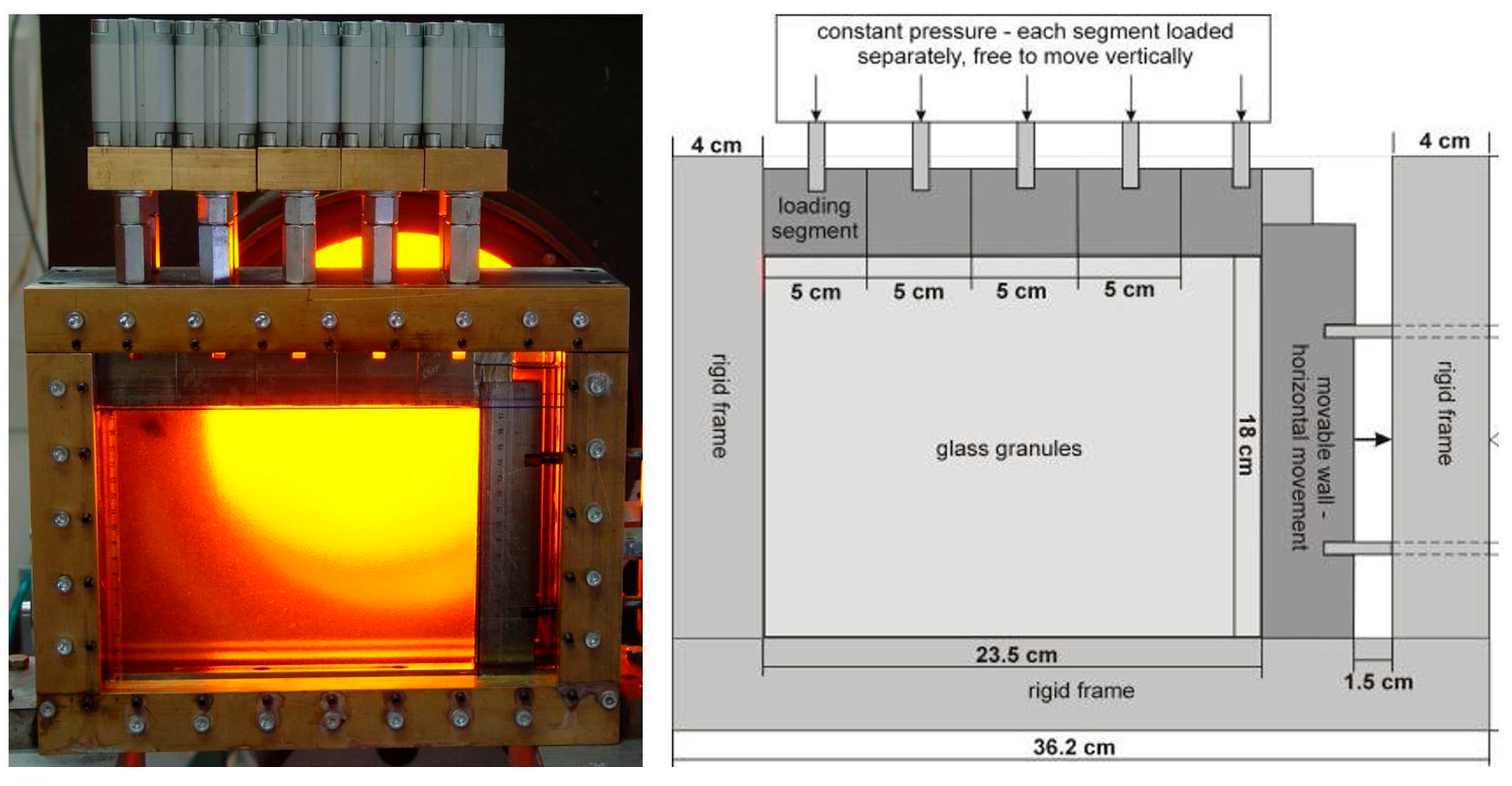

2.4. Experimental Setup for Model Tests

2.5. Experimental Materials

2.5.1. Granular Materials

2.5.2. Immersion Liquid

2.5.3. Model Test Procedure

- Forming the sample by pouring;

- Filling the model with immersion fluid;

- Applying the load elements;

- Connecting the elements to the loading head, through which pressure is applied using a hydraulic pump;

- Loading the model (load range—0–4.0 MPa; minimum load increment of 0.2 MPa),

- Moving the wall by rotating the support screw;

- Recording the individual stages of the experiment with a digital camera, in normal and polarised light.

3. Results and Discussion

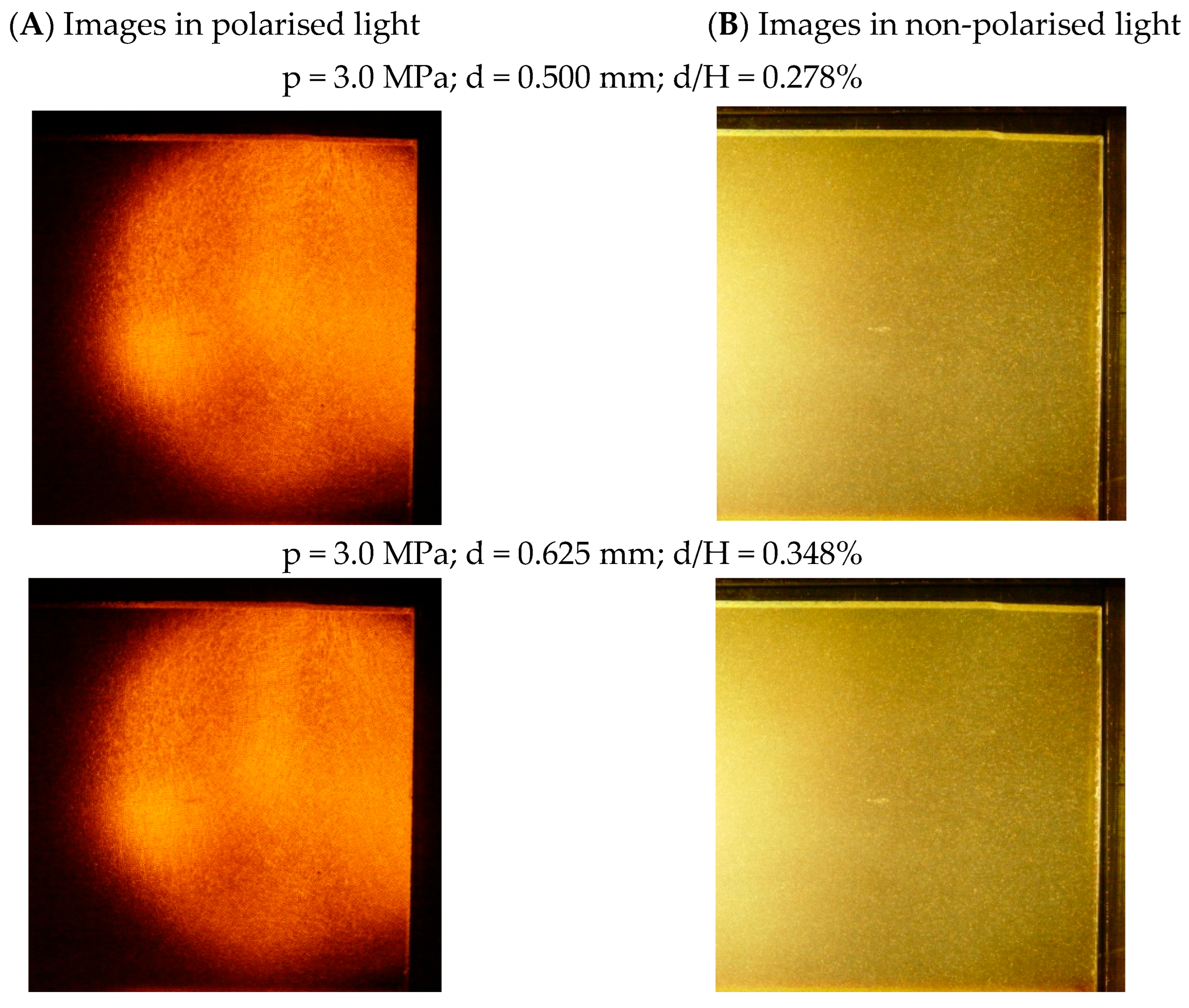

3.1. Experimental Results from the Model Tests

3.2. Results of Model Tests After Digital Processing

3.3. Strain and Stress Fields

4. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coulomb, C.A. Essai sur une Application des Regles des Maximis et Minimis a Quelques Problemes de Statique, Relatives a l’Architecture; Editions Science et Industrie: Paris, France, 1773; pp. 343–387. [Google Scholar]

- Desrues, J. Shear Band Initiation in Granular Material: Experimentation and Theory in Geomaterials: Constitutive Equations and Modelling; Darve, F., Ed.; Elsevier Applied Science: London, UK, 1990; pp. 283–310. [Google Scholar]

- Terzaghi, K.A. A fundamental fallacy in earth pressure computations. J. Boston Soc. Civ. Eng. 1936, 23, 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe, K.H. The influence of strains in soil mechanics. Geotechnique 1970, 20, 129–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichihara, M.; Matsuzawa, H. Application of plane strain test to earth pressure. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, Moscow, Russia, 6–11 August 1973; Volume 1, pp. 885–901. [Google Scholar]

- Sherif, M.A.; Ishibishi, I.; Lee, C.D. Earth pressure againsst rigid retaining walls. J. Geotech. Eng. Div. 1982, 108, 679–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.-S.; Ishibashi, I. Static earth pressure with various wall movements. J. Geotech. Eng. 1986, 112, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harr, M.E. Foundations of Theoretical Soil Mechanics; McGraw-Hill Book Co.: Columbus, OH, USA, 1966; Volume 381. [Google Scholar]

- James, R.G.; Bransby, P.L. A velocity field for some passive earth pressure problems. Geotechnique 1971, 21, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.R.F.; James, R.G.; Roscoe, K.H. The determination of stress fields during plane strain of sand mass. Geotechnique 1964, 14, 283–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.R.F.; Roscoe, K.H. An examination of the edge effects in plane-strain model earth pressure tests. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, Montreal, ON, Canada, 8–15 September 1965; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1965; Volume II, pp. 363–367. [Google Scholar]

- Bransby, P.L.; Milligan, G.W.E. Soil deformation near cantilever sheet pile walls. Geotechnique 1975, 25, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, G.W.E.; Bransby, P.L. Combined active and passive rotational failure of a retaining wall in sand. Geotechnique 1976, 26, 473–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, G.W.E. Soil deformations near anchored sheet-pile walls. Geotechnique 1983, 33, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leśniewska, D. Analysis of Shear Band Pattern Formation in Soil; Wydawnictwo IBW PAN w Gdańsku: Gdańsk, Poland, 2000; Volume 204. [Google Scholar]

- Sielamowicz, I.; Czech, M.; Kowalewski, T.A. Empirical analysis of eccentric flow registered by the DPIV technique inside a silo model. Powder Technol. 2011, 212, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balevičius, R.; Kačianauskas, R.; Mróz, Z.; Sielamowicz, I. Analysis and DEM simulation of granular material flow patterns in hopper models of different shapes. Adv. Powder Technol. 2011, 22, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, M.H.; Pipatpongsa, T.; Takemura, J. Experimental analysis of earth pressure against rigid retaining walls under translation mode. Géotechnique 2013, 63, 1020–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, S.H.; Weng, M.C.; Shih, M.H. Measuring the in situ deformation of retaining walls by the digital image correlation method. Eng. Geol. 2013, 166, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatami, H.; Deng, A.; Jaksa, M. An experimental study of the active arching effect in soil using the digital image correlation technique. Comput. Geotech. 2019, 108, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorn, G.N.; Bowman, A.; Haigh, S.K.; Stanier, S. Low-cost digital image correlation and strain measurement for geotechnical applications. Strain 2020, 56, e12348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Wu, C.; Ni, P.; Wan, G.; Zheng, A.; Jang, B.; Karekal, S. Experimental analysis of progressive failure behavior of rock tunnel with a fault zone using non-contact DIC technique. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2020, 132, 104355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanier, S.A.; Blaber, J.; Take, W.A.; White, D.J. Improved image-based deformation measurement for geotechnical applications. Can. Geotech. J. 2016, 53, 727–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, M.H.; Pipatpongsa, T.; Takemura, J. Theoretical analysis of earth pressure against rigid retaining walls under translation mode. Soils Found. 2016, 56, 664–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, M.H.; Bahaaddini, M.; Kargar, A.R.; Pipatpongsa, T. Soil arching behind retaining walls under active translation mode: Review and new insights. Int. J. Min. Geo-Eng. 2018, 52, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Chen, H.-b.; Chen, F.-q.; Lin, Y.-j.; Lin, C. An experimental study of the active failure mechanism of narrow backfills installed behind rigid retaining walls conducted using Geo-PIV. Acta Geotech. 2022, 17, 4051–4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Lin, Y.; Li, D. Solution to active earth pressure of narrow cohesionless backfill against rigid retaining walls under translation mode. Soils Found. 2019, 59, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Dang, F.; Cao, X.; Zhang, L.; Gao, J.; Xue, H. Solution for Active and Passive Earth Pressure on Rigid Retaining Walls with Narrow Backfill. Appl. Sci. 2024, 15, 1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Xu, Y.; Xing, Z.; Tang, W.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; et al. Study on active earth pressure of narrow backfill of balance weight retaining wall under translational displacement mode. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 18, 100430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, Y. Research on active earth pressure of narrow cohesionless backfill against rigid walls considering the arching effect. Front. Phys. 2025, 13, 1582886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Li, M.G.; Wang, J.H. Active earth pressure against rigid retaining walls subjected to confined cohesionless soil. Int. J. Geomech. 2017, 17, 06016041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Deb, K. Study of active earth pressure behind a vertical retaining wall subjected to rotation about the base. Int. J. Geomech. 2020, 20, 04020028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.; Basha, B. Experimental Study of Active Earth Pressure on Narrow Backfill Retaining Walls Under Rotation. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2025, 43, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wörden, F.; Achmus, M. Numerical modeling of three dimensional active earth thrust acting on rigid walls. Comput. Geotech. 2013, 51, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhong, Z.; Zhao, B.; Zeng, Z.; Gong, X.; Hu, S. Analysis of the Active Earth Pressure of Sandy Soil under the Translational Failure Mode of Rigid Retaining Walls Near Slopes. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 28, 5500–5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, A.A.; Bares, J.; Brzinski, T.A.; Daniels, K.E.; Dijksman, J.; Docquier, N.; Everitt, H.O.; Kollmer, J.E.; Lantsoght, O.; Wang, D.; et al. Enlightening force chains: A review of photoelasticimetry in granular matter. Granul. Matter 2019, 21, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, K.E.; Kollmer, J.E.; Puckett, J.G. Photoelastic force measurements in granular materials. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2017, 88, 051808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Juanes, R. Dynamic imaging of force chains in 3D granular media. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2319160121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, R.C.; Zhai, C. Challenges and opportunities in measuring time-resolved force chain evolution in 3D granular materials. Pap. Phys. 2022, 14, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, R.C.; Hall, S.A.; Andrade, J.E.; Wright, J. Quantifying Interparticle Forces and Heterogeneity in 3D Granular Materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 117, 098005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.L.; McCabe, L.; McMillan, B.; Naseer, A.; Xie, D.; Brzinski, T.; Daniels, K.E.; Murthy, T.; Nordstrom, K. Photoelastic Grain Solver v2.0: An updated tool for analysis of force measurements in granular materials. EPJ Web Conf. 2025, 340, 10004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Li, N.; Zhang, M.; Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y. Transparent Soil: A Review of Material Innovation, Optical Imaging Technique, and Multidisciplinary Application. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Zong, S.; Guo, J.; Miao, C. Discrete-Element Study on the Active Earth Pressure of Narrow Cohesionless Backfill against Rigid Retaining Walls. Int. J. Geomech. 2025, 25, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrian, R.J. Particle imaging techniques for experimental fluid mechanics. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 1991, 23, 261–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, D.J.; Take, W.A. GeoPIV: Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) Software for Use in Geotechnical Testing; Manual for GeoPIV, Technical Raport CUED/D-SOILS/TR322; Cambridge University Engineering Department: Cambridge, UK, 2002; 15p. [Google Scholar]

- Malesiński, K.; Zadroga, B. Stateczność Fundamentów Bezpośrednich Posadowionych na Zboczu z Gruntu Zbrojonego (Stability of Shallow Foundations Placed on a Reinforced Soil Slope); Gdańsk University of Technology Publishing House: Gdańsk, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Leśniewska, D.; Muir Wood, D. Observations of stresses and strains in a granular material. J. Eng. Mech. 2009, 135, 1038–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dereszkiewicz, R.S. Elastooptyka: Stan i Rozwój Polaryzacyjno-Optycznych Metod Doświadczalnej Analizy Naprężeń (Optical Elastochemistry: Status and Development of Polarization-Optical Methods for Experimental Stress Analysis); State Scientific Publishing House: Warsaw, Poland, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Leśniewska, D.; Muir Wood, D.; Pietrzak, M. Particle scale features in shearing of glass ballotini. AIP Conf. Proc. 2009, 1145, 335–338. [Google Scholar]

- Leśniewska, D.; Muir Wood, D. Photoelastic and photographic study of a granular material. Geotechnique 2011, 61, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir Wood, D.; Leśniewska, D. Stresses in granular materials. Granul. Matter 2011, 13, 395–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, M. Badanie pól Odkształceń i Naprężeń w Ośrodku Rozdrobnionym w Stanie Parcia Czynnego (Study of Strain and Stress Fields in a Fragmented Medium Under Active Pressure). Ph.D. Thesis, Koszalin University of Technology, Koszalin, Poland, 2014. Available online: https://dlibra.tu.koszalin.pl/dlibra/publication/1084/edition/1082/content (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Leśniewska, D.; Pietrzak, M. Experimental versus finite element approach to study scale dependent features in granular materials’ stress and deformation fields. In International Workshop on Bifurcation and Degradation in Geomaterials; Springer Series in Geomechanics and Geoengineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi, T. Photo-elastic Method for Determination of Stress in Powdered Mass. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1957, 5, 383–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drescher, A. An experimental investigation of flow rules for granular materials using optically sensitive glass particles. Geotechnique 1976, 26, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radosz, I.E.; Pietrzak, M.; Kaczmarek, L.M. Tests of Uniaxial Compression of Single Grains. Materials 2024, 17, 5479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantu, P. Contribution a l’etiude mecanique et geometrique des milieux pulverulents. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, London, UK, 12–14 August 1957; Volume 1, pp. 144–148. [Google Scholar]

- Leśniewska, D.; Pietrzak, M. Strains inside shear bands observed in tests on model retaining wall in active state. In Micro to MACRO Mathematical Modelling in Soil Mechanics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 257–265. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A.H.; Mort, P.; Behringer, R.P. Coarse graining for an impeller-driven mixer system. Granul. Matter 2012, 14, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, J. On the Modelling of Pile Installation. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Albaraki, S.; Antony, J.; Arowosola, B. Visualising shear stress distribution inside flow geometries containing pharmaceutical powder excipients using photo stress analysis tomography and DEM simulations. AIP Conf. Proc. 2013, 1542, 706–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, M. Cyclical changes in deformation process in granular material in active state. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 92, 17004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnicki, J.; Rice, J. Conditions for the localization of deformation in pressure-sensitive dilatant materials. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1975, 23, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardoulakis, I.; Exadaktylos, G.; Aifantis, E. Gradient elasticity with surface energy: Mode-III crack problem. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1996, 33, 4531–4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leśniewska, D.; Tordesillas, A.; Pietrzak, M.; Zhou, S.; Nitka, M. Structured deformation of granular material in the state of active earth pressure. Comput. Geotech. 2023, 157, 105316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Glass Granules | Median Grain Diameter (mm) | Uniformity Coefficient | Volumetric Weight of the Soil Skeleton () | Relative Sensity |

| 1.1 | 1.1 | 16.80 | 0.80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pietrzak, M. Experimental Studies of Strain and Stress Fields in a Granular Medium Under Active Pressure Using DIC and Elasto-Optic Methods. Materials 2026, 19, 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010172

Pietrzak M. Experimental Studies of Strain and Stress Fields in a Granular Medium Under Active Pressure Using DIC and Elasto-Optic Methods. Materials. 2026; 19(1):172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010172

Chicago/Turabian StylePietrzak, Magdalena. 2026. "Experimental Studies of Strain and Stress Fields in a Granular Medium Under Active Pressure Using DIC and Elasto-Optic Methods" Materials 19, no. 1: 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010172

APA StylePietrzak, M. (2026). Experimental Studies of Strain and Stress Fields in a Granular Medium Under Active Pressure Using DIC and Elasto-Optic Methods. Materials, 19(1), 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010172