Strength and Ductility Enhancement in Coarse-Aggregate UHPC via Fiber Hybridization: Micro-Mechanistic Insights and Artificial Neural Network Prediction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

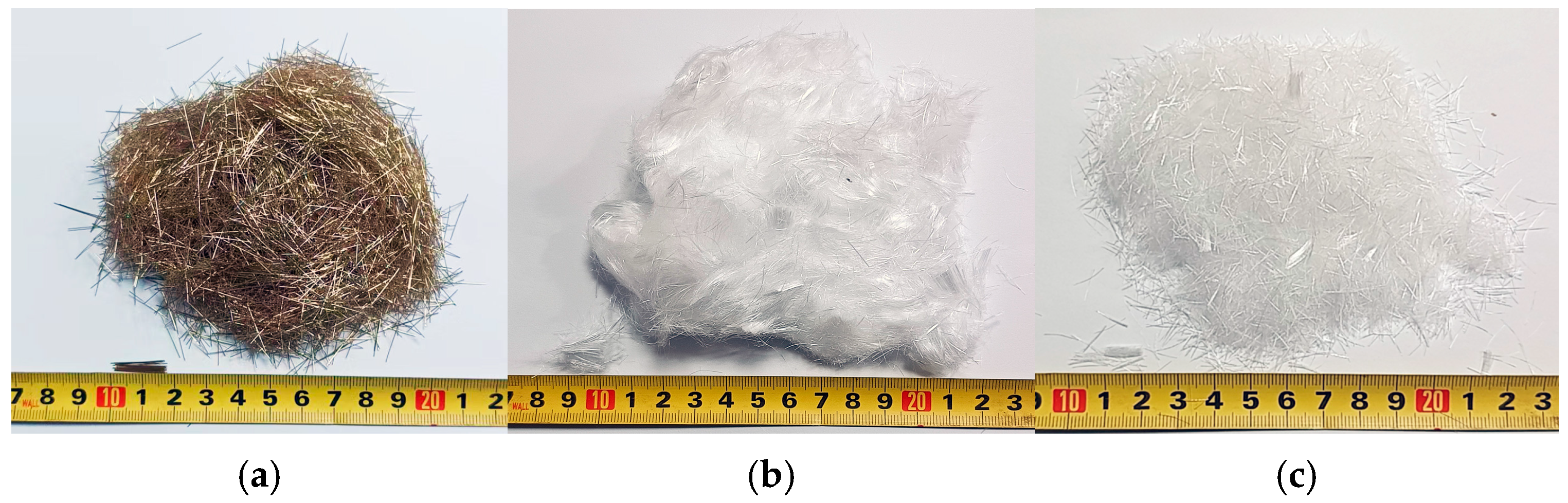

2.1. Raw Materials

2.2. Orthogonal Experimental Design

2.3. Specimen Preparation and Curing

2.4. Mechanical Property Testing

2.5. Microstructural Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Failure Modes and Mechanisms

3.2. Range Analysis and Mechanistic Interpretation

3.2.1. Range Analysis Results and Comprehensive Evaluation

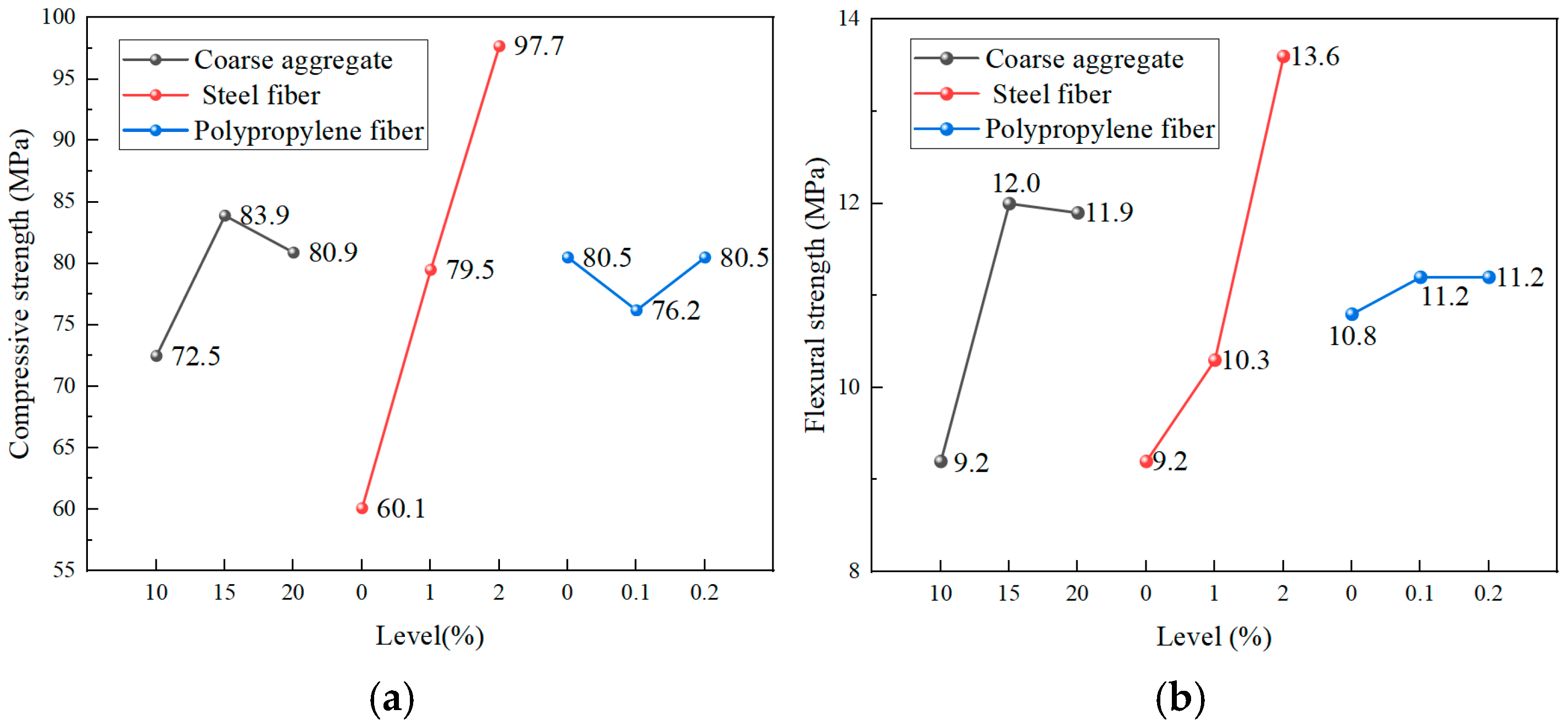

Phase I: Optimization of the Aggregate–Fiber System

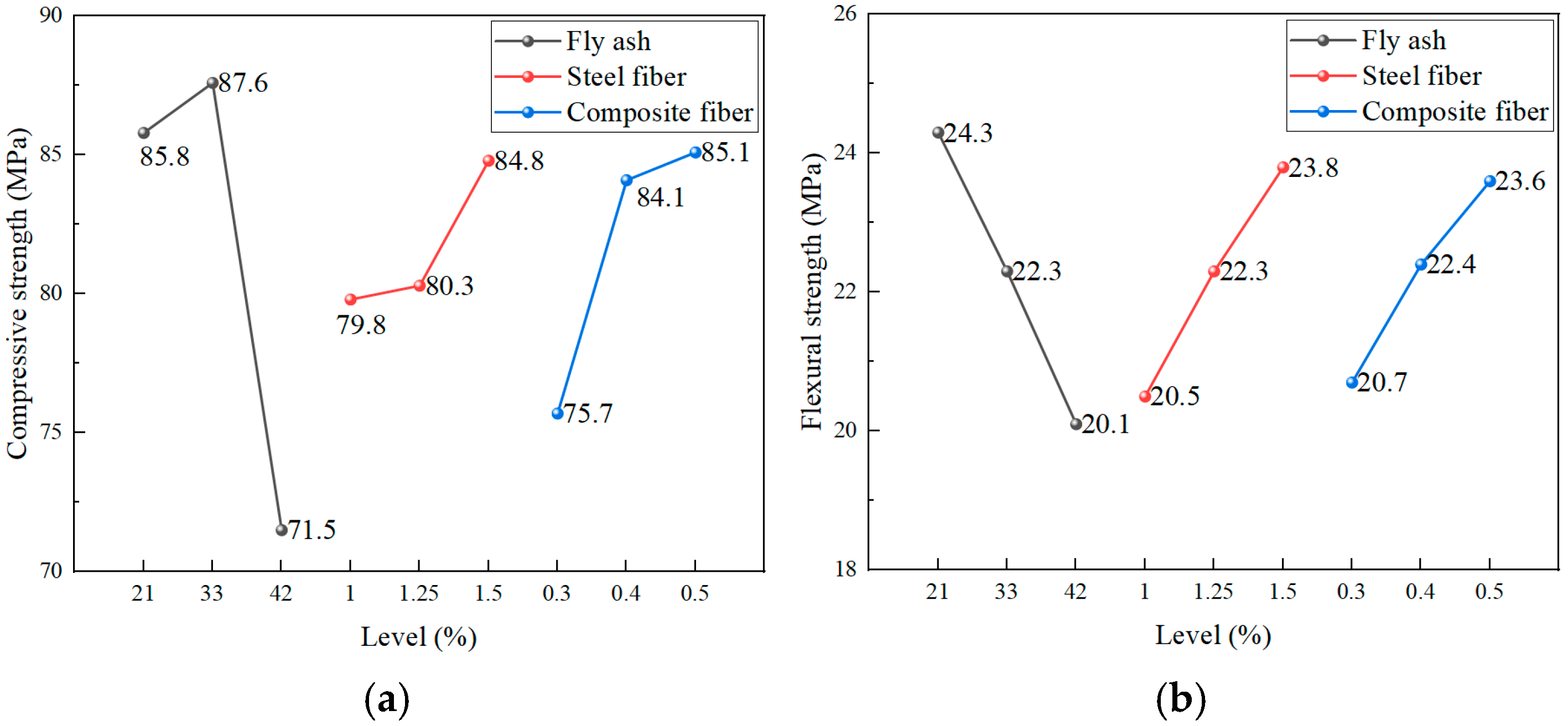

Phase II: Optimization of the Cementitious Material–Composite Fiber System

3.2.2. Analysis of Key Parameter Influence Mechanisms

Mechanisms of Matrix Constituents

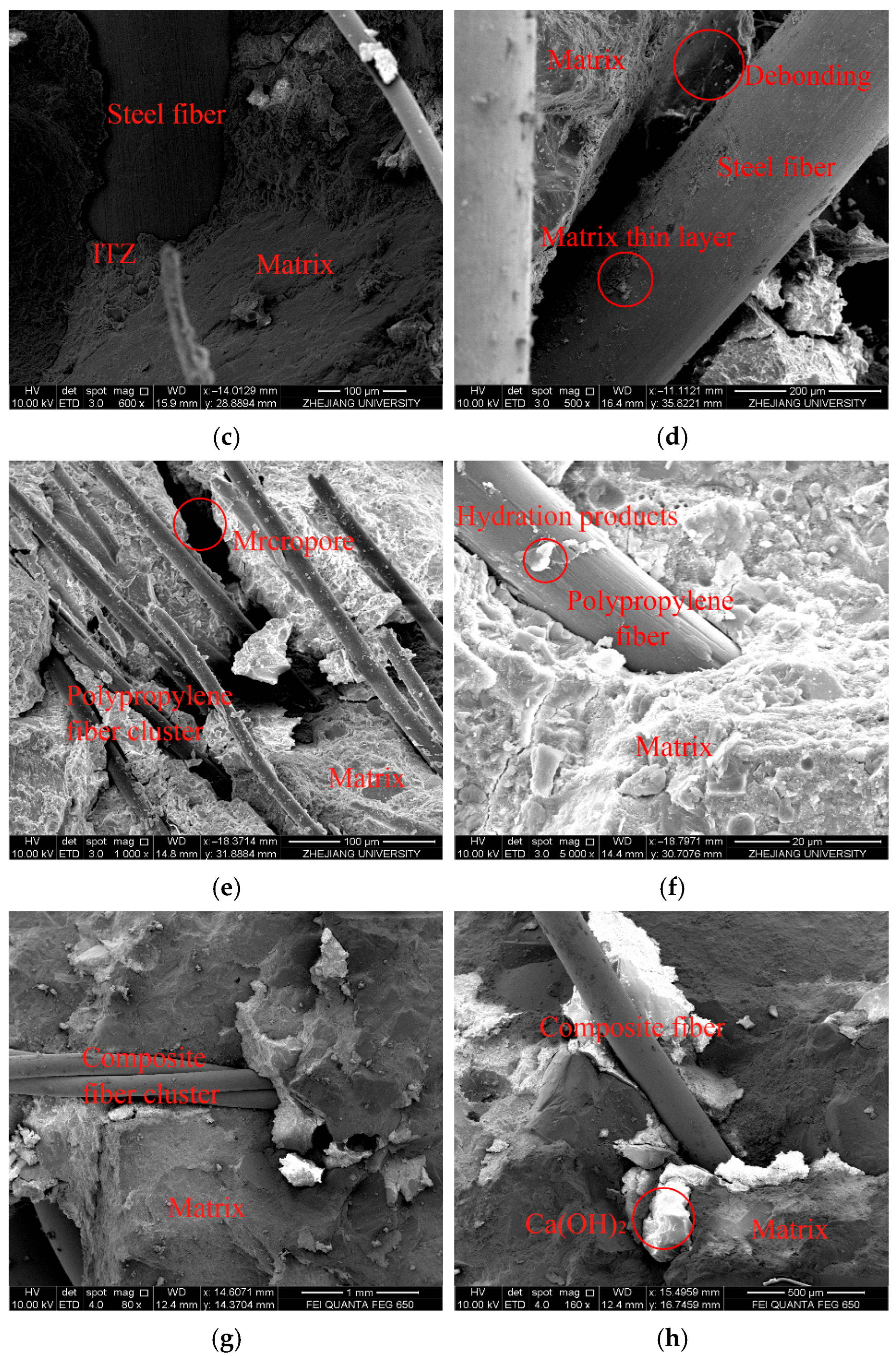

Mechanisms of Fiber Reinforcement

3.2.3. Comparative Analysis of Hybrid Fiber Systems

3.3. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

3.3.1. Phase I Analysis

3.3.2. Phase II Analysis

3.3.3. Comparative Interpretation

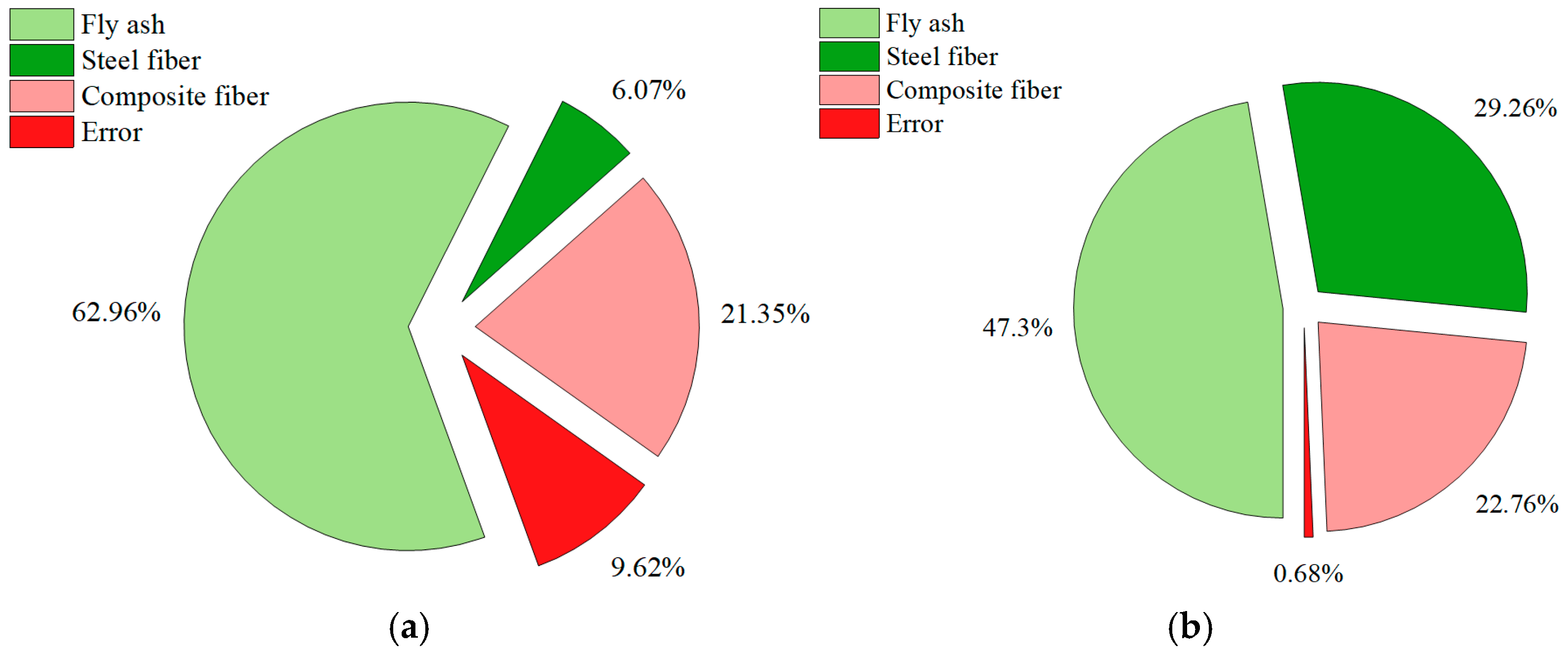

3.3.4. Contribution Analysis Based on ANOVA Results

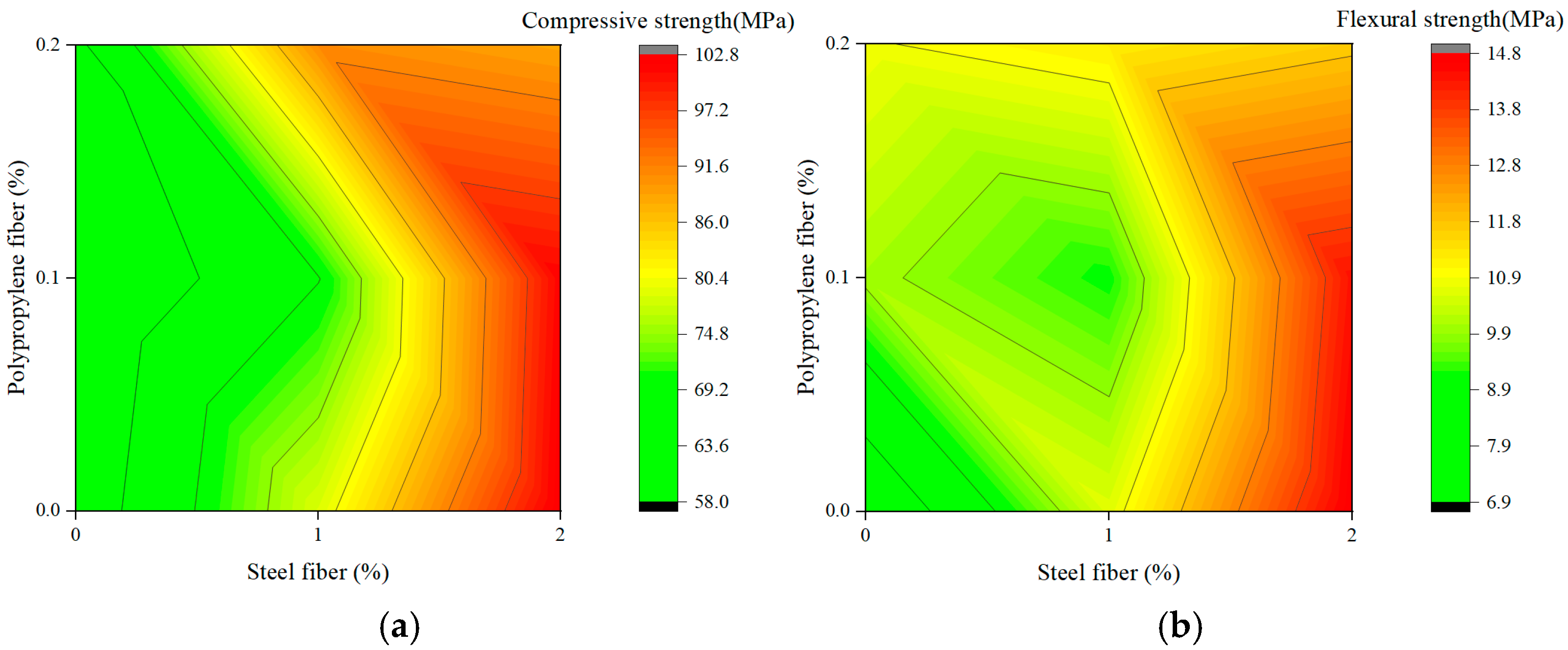

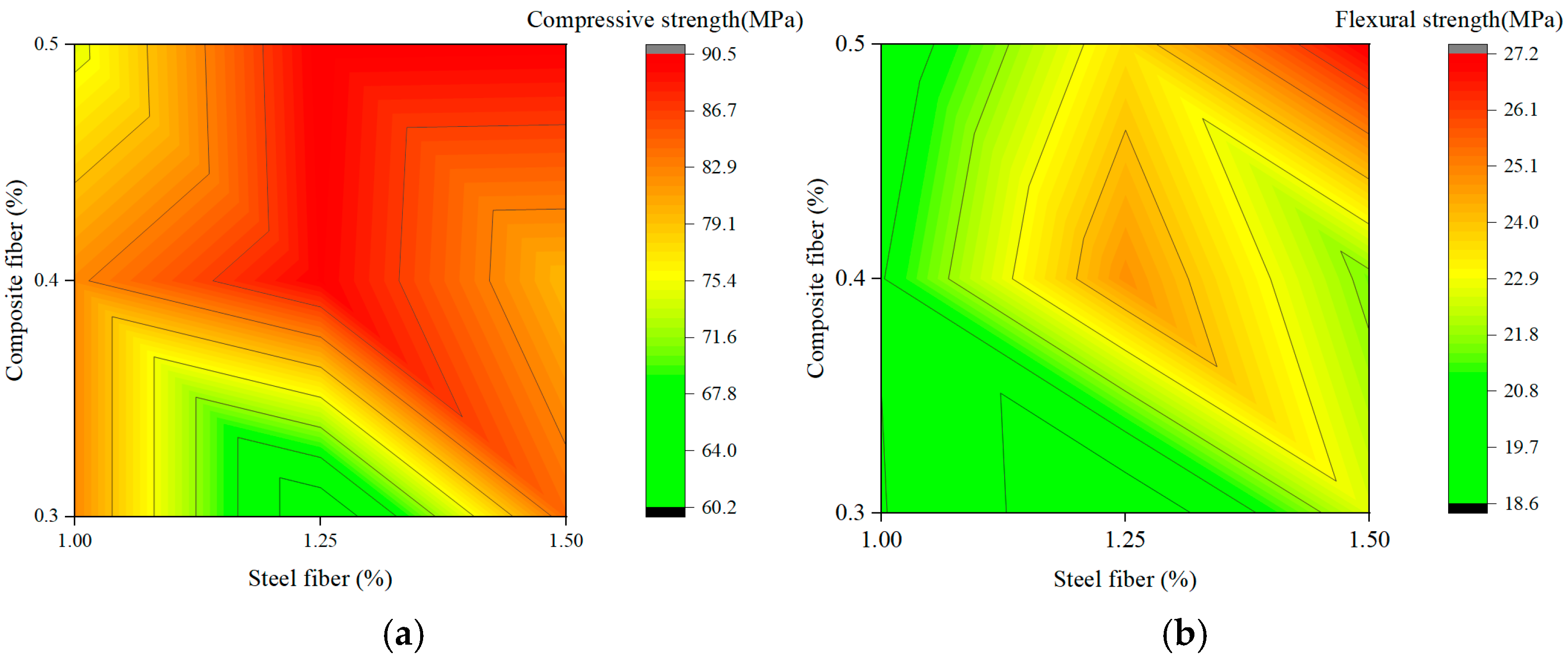

3.4. Analysis of Fiber Interaction Effects Using Contour Maps

3.4.1. Interaction Between Steel Fiber and Polypropylene Fiber

3.4.2. Interaction Between Steel Fiber and Composite Fiber

3.4.3. Comparative Discussion

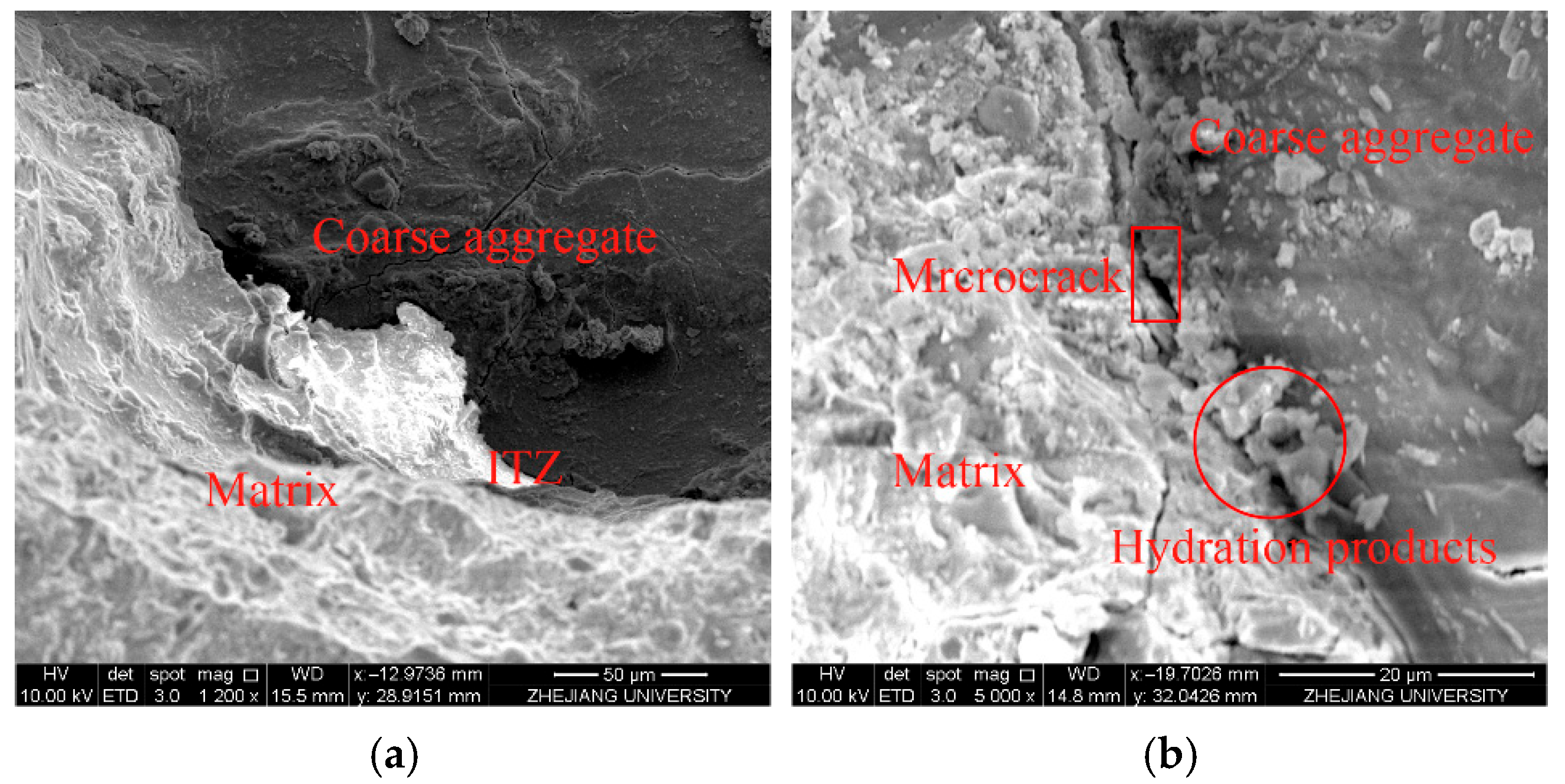

3.5. Microstructural Characterization and Analysis

3.5.1. Microstructural Characterization of ITZ by SEM Observation

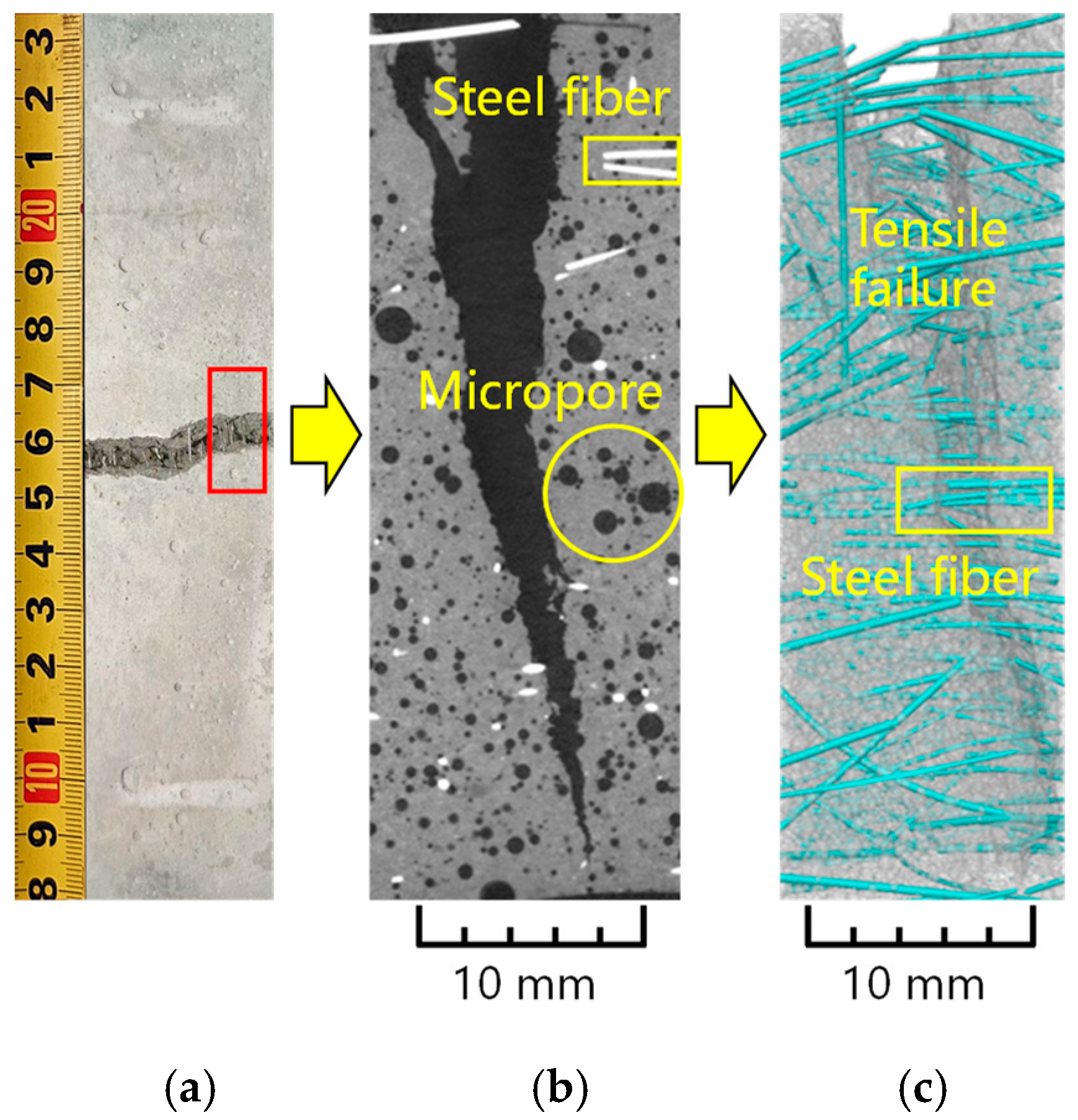

3.5.2. X-CT Analysis of Flexural Crack Development and Fiber Failure

3.6. Machine Learning-Based Strength Prediction

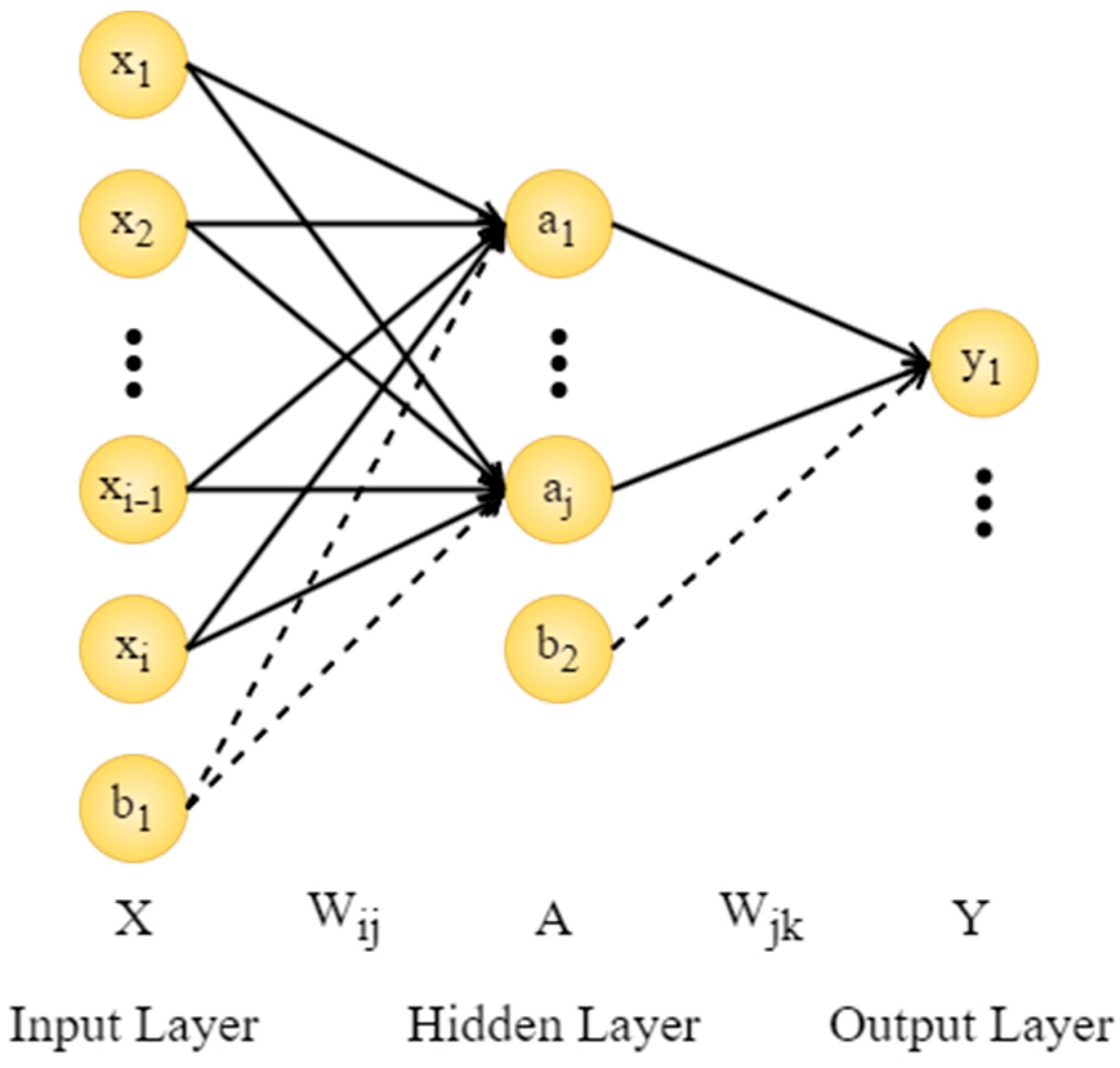

3.6.1. Artificial Neural Network

3.6.2. Dataset and Evaluation Metrics

3.6.3. Training Process

- (1)

- Data normalization. All input features were normalized to eliminate scale differences and improve convergence stability. The Z-score normalization method was adopted, as expressed in Equation (6):

- (2)

- Data partitioning. The entire dataset (50 samples) was randomly divided into two subsets: 80% for training and 20% for validation. The random sampling process was repeated five times to verify stability and reduce selection bias. Cross-validation [35] further ensured that the trained model had robust generalization capability and avoided overfitting.

- (3)

- Network structure and optimization. Each MLP model comprised one input layer, one hidden layer, and one output layer. The input layer contained seven neurons corresponding to the seven experimental variables, while the output layer contained one neuron representing the predicted strength. The number of hidden neurons, denoted as m, was varied within the range [1, 10] to determine the optimal topology. The network optimization loss function, shown in Equation (7), was used to minimize prediction error during training [36]:

- (4)

- Training and evaluation. The model employed the sigmoid activation function and used RMSE as the performance criterion. Learning rate was set to 0.1 based on empirical trials to ensure stable convergence. The training process was executed over multiple epochs. To ensure convergence and prevent overfitting, training was terminated after the model’s RMSE stabilized for more than 50 epochs. The stopping epoch was chosen based on the accuracy–cost trade-off observed during training (with an upper epoch cap), rather than an unjustified fixed rule. As shown in Table 13, multiple network structures were evaluated (e.g., 7-4-1, 7-8-1, 7-12-1), and their RMSE values were compared.

- (5)

- Model optimization and selection. According to the training outcomes summarized in Table 13, the optimal network topology was 7-12-1, comprising seven input neurons, 12 hidden neurons, and one output neuron. This configuration achieved the lowest RMSE of 2.17, indicating high prediction accuracy and stable generalization.

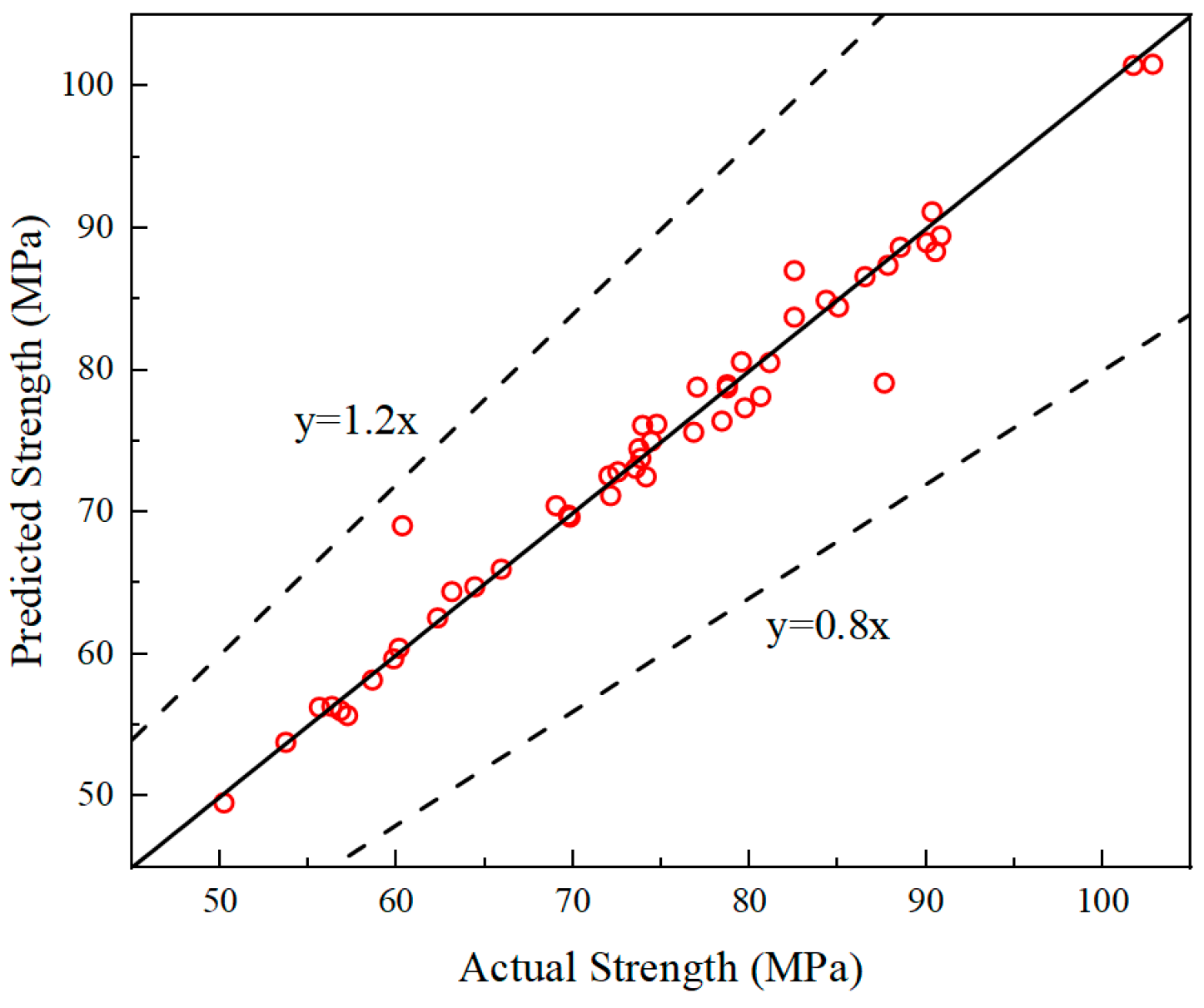

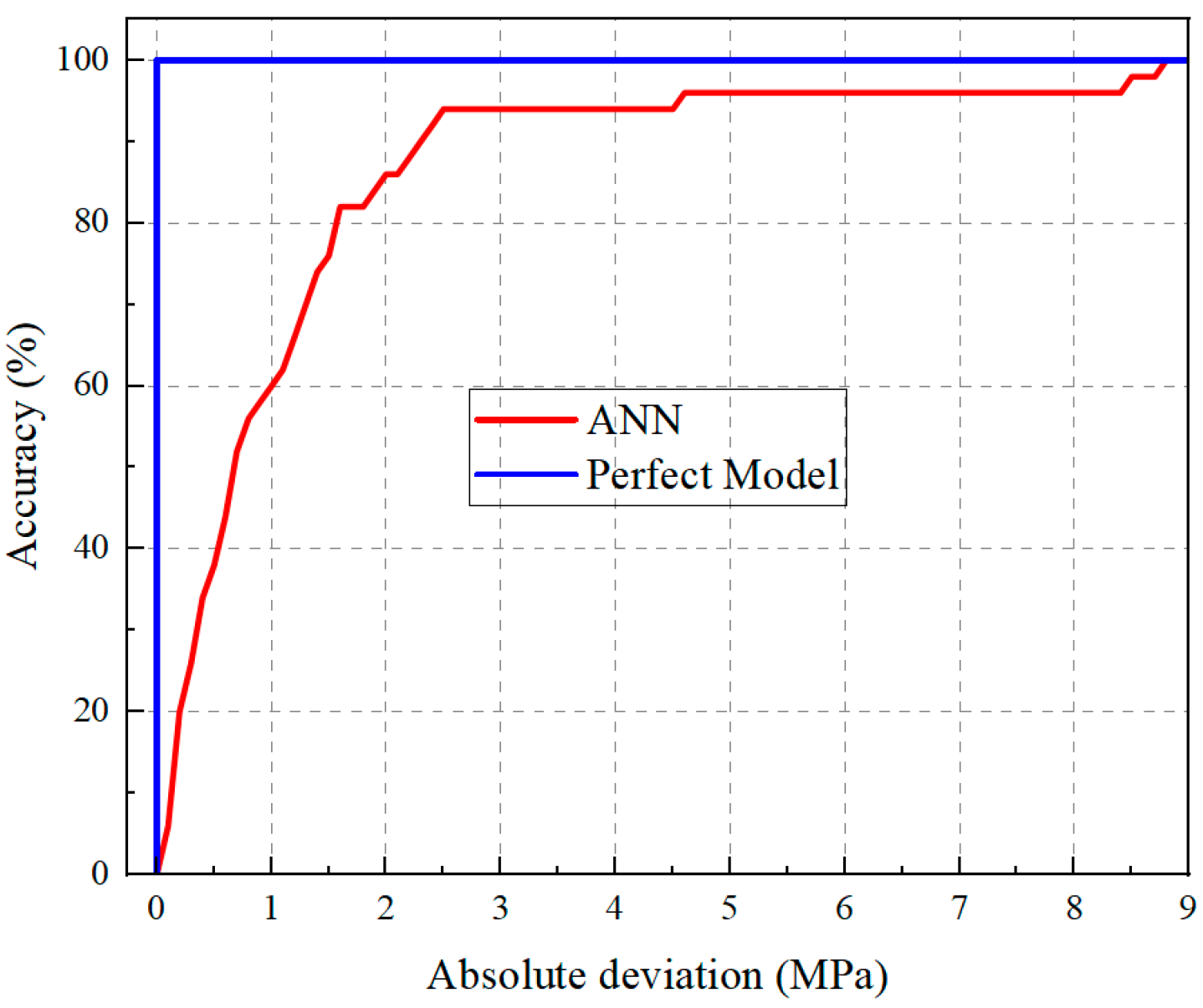

3.6.4. Performance Evaluation

3.6.5. Model Interpretability and Feature Importance Analysis Based on SHAP Values

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Synergistic Reinforcement and Quantitative Enhancement: The hybrid system combining steel and composite fibers demonstrated superior performance compared to the traditional steel–polypropylene combination. Specifically, the hybrid group achieved a 12.4% increase in compressive strength and a 14% improvement in flexural strength. This suggests that the partial substitution of steel fibers with composite fibers is a viable strategy for balancing cost and ductility. However, the optimal substitution ratio is sensitive to the total fiber volume.

- (2)

- Coupled Optimization of Fly Ash and Fibers: Fly ash functions beyond a mere filler; its optimal dosage (21–33%) densifies the matrix and refines the fiber–matrix interface. The study demonstrates that mineral admixtures and fiber systems exhibit strong coupled effects on strength development, necessitating a co-optimization approach rather than independent parameter selection to maximize packing density and bonding efficiency.

- (3)

- Microstructural Mechanisms of Ductility: SEM and X-CT analyses provide physical evidence connecting macroscopic performance to micromorphology. The enhancement in ductility is attributed to a densified ITZ and a multi-scale crack-bridging network. The hybrid fibers were observed to alter the failure mode from brittle fracture to controlled ductile rupture, physically supporting the multi-crack propagation behavior observed in the mechanical tests.

- (4)

- Data-Driven Prediction via ANN: The developed ANN model effectively captured the non-linear interactions among mix parameters, achieving a high accuracy with an R2 of 0.9703 and an RMSE of 2.11 MPa for compressive strength. The sensitivity analysis further identified that fiber volume and fly ash content are the most critical variables affecting the mechanical output within the tested domain.

- (5)

- Limitations and Future Perspectives: While the proposed framework shows promise, it is essential to note the limitations regarding the sample size and data distribution. The current ANN model provides reliable predictions within the specific parameter range of this study; however, extrapolation to mix designs with significantly different aggregate types or fiber geometries may introduce errors and require caution. Therefore, future work should focus on expanding the dataset to improve model generalization. Additionally, to complement the current microstructural analysis, future studies should incorporate in situ micromechanical characterization (e.g., fiber pull-out tests within an SEM or nanoindentation) to provide a more dynamic understanding of interface behavior. Finally, investigating the long-term durability (e.g., chloride resistance) of the UHPC-CA hybrid fiber system is also recommended for practical applications.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Su, X.; Ren, Z.G.; Li, P.P. Review on physical and chemical activation strategies for ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC). Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 149, 105519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DE Larrard, F.; Sedran, T. Optimization of ultra-high-performance concrete by the use of a packing model. Cem. Concr. Res. 1994, 24, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Meng, M.N.; Khayat, K.H.; Bao, Y.; Guo, P.; Lyu, Z.; Abu-Obeidah, A.; Nassif, H.; Wang, H. New development of ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC). Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 224, 109220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.M.; Sharhan, H.; Wang, J.Y.; Chen, Z.Y. Seismic performance and shear capacity prediction of SFRC shear walls with different door openings. Structures 2025, 72, 108189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Xu, Y.H.; Wang, S.B.; Zhang, W.Y.; Ji, X.H.; Zhang, B. Effect of high-strength rebar and ultra-high-performance concrete on blast resistance of slabs under contact explosion loads. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2025, 198, 105230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Shi, C.J.; Wu, Z.M. Mitigation techniques for autogenous shrinkage of ultra-high-performance concrete—A review. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 178, 107456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.Y.; Banthia, N. Mechanical properties of ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete: A review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 73, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.P.; Yu, Q.L.; Brouwers, H.J.H. Effect of coarse basalt aggregates on the properties of ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 170, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.C.; Yang, I.H.; Joh, C. Effect of single and hybrid steel fiber lengths and fiber contents on the mechanical properties of high-strength fiber-reinforced concrete. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2018, 2018, 7826156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Li, J.; Wu, C.Q.; Liu, Z.X.; Li, J. Hybrid fibre reinforced ultra-high performance concrete beams under static and impact loads. Eng. Struct. 2021, 245, 112921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.G.; Wang, Z.Y.; Zhu, Z.Y.; Guo, Q.Y.; Wu, X.R.; Zhao, R.D. Research on different types of fiber reinforced concrete in recent years: An overview. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 365, 130075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W.; Li, S.J.; Peng, H.J. Experimental investigation of multiscale hybrid fibres on the mechanical properties of high-performance concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 299, 123895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.W.; Xi, B.; Yu, K.Q.; Sui, L.L.; Xing, F. Mechanical properties of hybrid ultra-high performance engineered cementitious composites incorporating steel and polyethylene fibers. Materials 2018, 11, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alwsabi, E.A.H.; Abu Bakar, B.H.; Alshaikh, I.M.H.; Abadel, A.A.; Alghamdi, H.; Wasim, M. An experimental study of compressive toughness of steel-polypropylene hybrid fibre-reinforced concrete. Structures 2022, 37, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, W.; Morimoto, H. Effects of various fibres on high-temperature spalling in high-performance concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 71, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.W.; He, X.J.; Yi, Z.J.; Zhu, Z.W.; He, J.; Wang, W.; Zhao, C.H. Flexural fatigue behaviors of high-content hybrid fiber-polymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 349, 128772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.Q.; Xu, L.H.; Chi, Y.; Wu, F.H.; Chen, Q. Effect of steel-polypropylene hybrid fiber and coarse aggregate inclusion on the stress–strain behavior of ultra-high performance concrete under uniaxial compression. Compos. Struct. 2020, 252, 112685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, D.; Prem, P.R.; Kaliyavaradhan, S.K.; Ambily, P.S. Influence of fibers on fresh and hardened properties of Ultra High Performance Concrete (UHPC)-A review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 57, 104922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asteris, P.G.; Skentou, A.D.; Bardhan, A.; Samui, P.; Pilakoutas, K. Predicting concrete compressive strength using hybrid ensembling of surrogate machine learning models. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 145, 106449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Yang, M.; Shang, X.W.; Xiong, Y.M.; Zhang, Y.Y. Predicting the compressive strength of UHPC with coarse aggregates in the context of machine learning. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, L.T.; Du, G.Q.; Hou, Q. Prediction of the compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete based on artificial neural network. Materials 2021, 14, 3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chithra, S.; Kumar, S.R.R.S.; Chinnaraju, K.; Ashmita, F.A. A comparative study on the compressive strength prediction models for High Performance Concrete containing nano silica and copper slag using regression analysis and Artificial Neural Networks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 114, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omran, B.A.; Chen, Q.; Jin, R.Y. Comparison of data mining techniques for predicting compressive strength of environmentally friendly concrete. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2016, 30, 04016029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.V.; Rao, K.B.; Nayak, G. Prediction of recycled coarse aggregate concrete mechanical properties using multiple linear regression and artificial neural network. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2021, 21, 1690–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H.A.; Nehdi, M.L.; Khan, M.I.; Akmal, U.; Alabduljabbar, H.; Mohamed, A.; Sheraz, M. Predicting compressive and splitting tensile strengths of silica fume concrete using M5P model tree algorithm. Materials 2022, 15, 5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnood, A.; Golafshani, E.M. Machine learning study of the mechanical properties of concretes containing waste foundry sand. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 243, 118152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, M.; Vanneschi, L.; Silva, S. Prediction of high performance concrete strength using Genetic Programming with geometric semantic genetic operators. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 6856–6862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.G.; Yuan, A.M.; Wang, K.Q.; Chen, Q.; Wang, X.; Kong, H.; Wang, J.Q. Mechanical and autogenous shrinkage properties of coarse aggregate ultra-high performance concrete (CA-UHPC): The effect of mineral admixtures. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.F.; Hua, Q.; Wu, Z.G.; Yu, Y.H.; Kang, A.H.; Chen, X.; Dong, H. Effect of basalt/steel individual and hybrid fiber on mechanical properties and microstructure of UHPC. Materials 2024, 17, 3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, K.X.; Chen, S.; Wang, C.; Yang, B.W.; Jiang, J.H. Optimal design of multi-scale fibre-reinforced cement-matrix composites based on an orthogonal experimental design. Polymers 2023, 15, 2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T/CBMF 37-2018; Fundamental Characteristics and Test Method of Ultra-High Performance Concrete. China Building Materials Federation: Beijing, China, 2018. (In Chinese)

- GB/T 50081-2019; Standard of Test Methods of Concrete Physical and Mechanical Properties. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese)

- ASTM C1856/C1856M-17; Standard Practice for Fabricating and Testing Specimens of Ultra-High Performance Concrete. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- Asteris, P.G.; Ashrafian, A.; Rezaie-Baif, M. Prediction of the compressive strength of self-compacting concrete using surrogate models. Comput. Concr. 2019, 24, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.S.; Chiu, C.K.; Farfoura, M.; Al-Taharwa, I. Optimizing the prediction accuracy of concrete compressive strength based on a comparison of data-mining techniques. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2011, 25, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.B.; Duan, J.; Fan, T.; Jiao, P.F.; Dong, T.Y.; Wu, Q. Using GA-BP coupling algorithm to predict the high-performance concrete mechanical property. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2023, 27, 684–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, R.; Rai, B.; Samui, P. Prediction of compressive strength of high-volume fly ash self-compacting concrete with silica fume using machine learning techniques. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 438, 136933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilloulin, B.; Tran, V. Using machine learning techniques for predicting autogenous shrinkage of concrete incorporating superabsorbent polymers and supplementary cementitious materials. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 49, 104086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Insoluble Matter | Loss on Ignition | MgO | S2O3 | Chloride Ion | Limestone | Natural Gypsum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.95 | 2.13 | 1.46 | 2.59 | 0.019 | 2.16 | 6.54 |

| Moisture Content | Loss on Ignition | Water Requirement Ratio | S2O3 | Free CaO | Total Mass Fraction of SiO2, Al2O3, and Fe2O3 | 28 d Activity Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.02 | 1.80 | 93 | 0.7 | 0.05 | 77 | 79 |

| SiO2 | Fe2O3 | Al2O3 | TiO2 | CaO | MgO | Na2O | K2O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 93.0 | 0.31 | 4.63 | 0.057 | 0.23 | 0.12 | 1.38 | 2.18 |

| Fiber Types | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Length (mm) | Equivalent Diameter (mm) | Initial Modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steel | 2850 | 13.0 | 0.220 | 200 |

| Polypropylene | >350 | 19.0 | 0.034 | >3.5 |

| Polyethylene–polypropylene | 632 | 12.95 | 0.021 | 13.2 |

| Cement | Fly Ash | Silica Fume | Sand | Coarse Aggregate | Steel Fiber | Plasticizer | Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 600 | 100 | 50 | 1000 | 450 | 156 | 5 | 250 |

| Specimen | Coarse Aggregate (%) | Steel Fiber (%) | Polypropylene Fiber (%) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Flexural Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 60.1 | 6.9 |

| A-2 | 10 | 1 | 0.1 | 69.0 | 9.1 |

| A-3 | 10 | 2 | 0.2 | 88.5 | 11.7 |

| A-4 | 15 | 0 | 0.1 | 58.0 | 10.0 |

| A-5 | 15 | 1 | 0.2 | 90.8 | 11.2 |

| A-6 | 15 | 2 | 0 | 102.8 | 14.8 |

| A-7 | 20 | 0 | 0.2 | 62.3 | 10.8 |

| A-8 | 20 | 1 | 0 | 78.7 | 10.6 |

| A-9 | 20 | 2 | 0.1 | 101.7 | 14.4 |

| Specimen | Fly Ash (%) | Steel Fiber (%) | Composite Fiber (%) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Flexural Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-1 | 21 | 1 | 0.3 | 82.5 | 20.8 |

| B-2 | 21 | 1.25 | 0.4 | 90.0 | 24.8 |

| B-3 | 21 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 90.3 | 27.2 |

| B-4 | 33 | 1 | 0.4 | 82.5 | 20.7 |

| B-5 | 33 | 1.25 | 0.5 | 90.5 | 23.5 |

| B-6 | 33 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 84.3 | 22.6 |

| B-7 | 42 | 1 | 0.5 | 74.4 | 20.0 |

| B-8 | 42 | 1.25 | 0.3 | 60.3 | 18.6 |

| B-9 | 42 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 79.7 | 21.6 |

| Index | Level | Coarse Aggregate | Steel Fiber | Polypropylene Fiber |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compressive strength (MPa) | K1 | 72.5 | 60.1 | 80.5 |

| K2 | 83.9 | 79.5 | 76.2 | |

| K3 | 80.9 | 97.7 | 80.5 | |

| R | 11.4 | 37.6 | 4.3 | |

| Flexural strength (MPa) | K1 | 9.2 | 9.2 | 10.8 |

| K2 | 12.0 | 10.3 | 11.2 | |

| K3 | 11.9 | 13.6 | 11.2 | |

| R | 2.8 | 4.4 | 0.4 |

| Index | Level | Fly Ash | Steel Fiber | Composite Fiber |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compressive strength (MPa) | K1 | 85.8 | 79.8 | 75.7 |

| K2 | 87.6 | 80.3 | 84.1 | |

| K3 | 71.5 | 84.8 | 85.1 | |

| R | 16.1 | 5.0 | 9.4 | |

| Flexural strength (MPa) | K1 | 24.3 | 20.5 | 20.7 |

| K2 | 22.3 | 22.3 | 22.4 | |

| K3 | 20.1 | 23.8 | 23.6 | |

| R | 4.2 | 3.3 | 2.9 |

| Index | Factor | SS | DOF | MS | F | Fa(2,2) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compressive strength | Coarse aggregate | 207.25 | 2 | 103.63 | 1.59 | 0.19 | |

| Steel fiber | 2113.85 | 2 | 1056.93 | 16.23 | 0.05 | (*) | |

| Polypropylene fiber | 36.98 | 2 | 18.49 | 0.28 | 0.02 | ||

| Error | 130.24 | 2 | 65.12 | ||||

| Flexural strength | Coarse aggregate | 14.95 | 2 | 7.48 | 12.68 | 0.19 | (*) |

| Steel fiber | 31.61 | 2 | 15.81 | 26.80 | 0.05 | (*) * | |

| Polypropylene fiber | 0.38 | 2 | 0.19 | 0.32 | 0.02 | ||

| Error | 1.18 | 2 | 0.59 |

| Index | Factor | SS | DOF | MS | F | Fa(2,2) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compressive strength | Fly ash | 468.14 | 2 | 234.07 | 6.55 | 0.19 | |

| Steel fiber | 45.14 | 2 | 22.57 | 0.63 | 0.05 | ||

| Composite fiber | 158.74 | 2 | 79.37 | 2.22 | 0.02 | ||

| Error | 71.49 | 2 | 35.75 | ||||

| Flexural strength | Fly ash | 26.48 | 2 | 13.24 | 69.68 | 0.19 | (*) * |

| Steel fiber | 16.38 | 2 | 8.19 | 43.11 | 0.05 | (*) * | |

| Composite fiber | 12.74 | 2 | 6.37 | 33.53 | 0.02 | (*) * | |

| Error | 0.38 | 2 | 0.19 |

| Parameter | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water-binder ratio | 0.33 | 0.27 | / | / | / |

| Fly ash (%) | 17 | 21 | 33 | 42 | / |

| Coarse aggregate (%) | 10 | 15 | 20 | / | / |

| Steel fiber (%) | 0 | 1 | 1.25 | 1.5 | 2 |

| Polypropylene fiber (%) | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | / | / |

| Composite fiber (%) | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | / | / |

| Age (d) | 7 | 14 | 28 | / | / |

| Network Topology | RMSE |

|---|---|

| 7-4-1 | 6.73 |

| 7-5-1 | 4.19 |

| 7-6-1 | 4.68 |

| 7-7-1 | 4.63 |

| 7-8-1 | 2.83 |

| 7-9-1 | 2.60 |

| 7-10-1 | 3.02 |

| 7-11-1 | 2.84 |

| 7-12-1 | 2.17 |

| Network Topology | RMSE | MAE | R2 | a20-Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7-12-1 | 2.11 | 1.22 | 0.9703 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhan, Y.; Peng, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, B. Strength and Ductility Enhancement in Coarse-Aggregate UHPC via Fiber Hybridization: Micro-Mechanistic Insights and Artificial Neural Network Prediction. Materials 2026, 19, 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010157

Wang J, Wang Y, Wang S, Zhan Y, Peng Y, Hu Z, Zhang B. Strength and Ductility Enhancement in Coarse-Aggregate UHPC via Fiber Hybridization: Micro-Mechanistic Insights and Artificial Neural Network Prediction. Materials. 2026; 19(1):157. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010157

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jiyang, Yalong Wang, Shubin Wang, Yijian Zhan, Yu Peng, Zhihua Hu, and Bo Zhang. 2026. "Strength and Ductility Enhancement in Coarse-Aggregate UHPC via Fiber Hybridization: Micro-Mechanistic Insights and Artificial Neural Network Prediction" Materials 19, no. 1: 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010157

APA StyleWang, J., Wang, Y., Wang, S., Zhan, Y., Peng, Y., Hu, Z., & Zhang, B. (2026). Strength and Ductility Enhancement in Coarse-Aggregate UHPC via Fiber Hybridization: Micro-Mechanistic Insights and Artificial Neural Network Prediction. Materials, 19(1), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010157