Thermoanalytical and Tensile Strength Studies of Polypropylene Fibre-Reinforced Cement Composites Designed for Tunnel Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

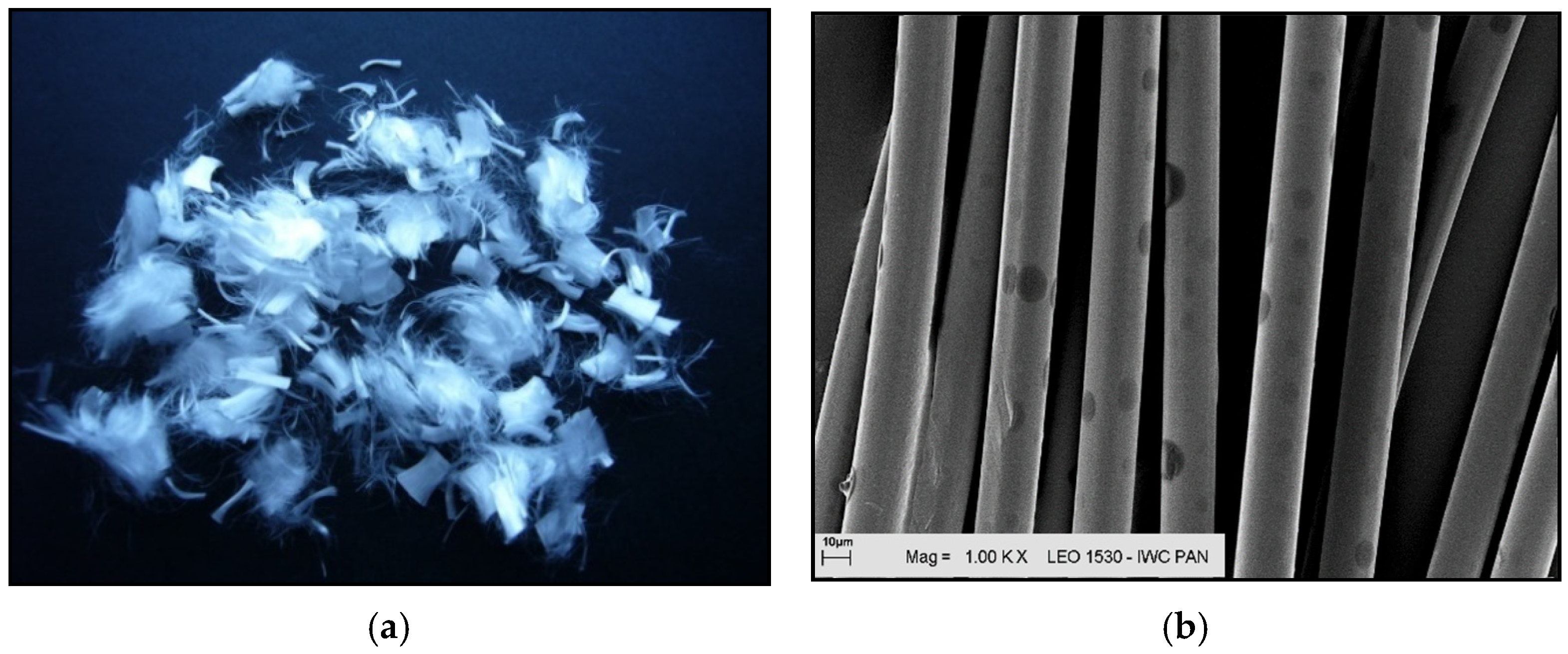

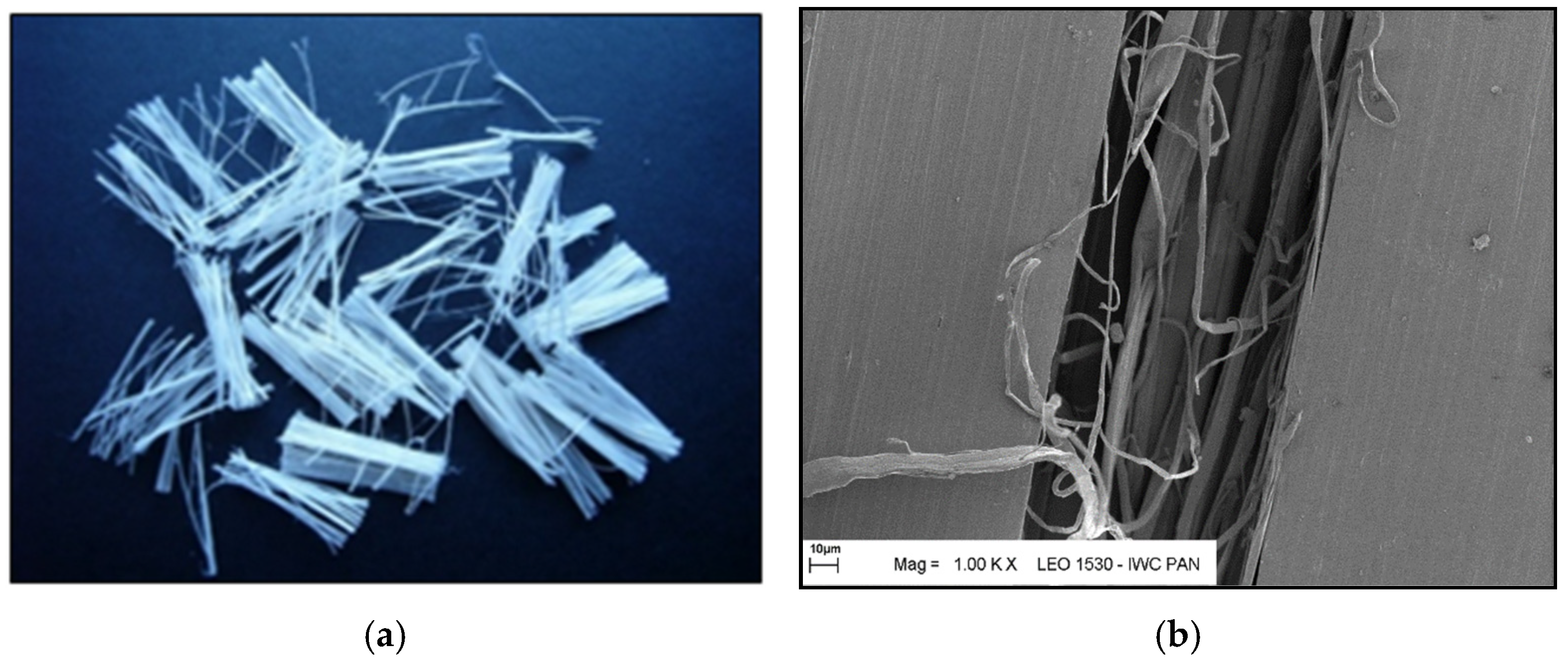

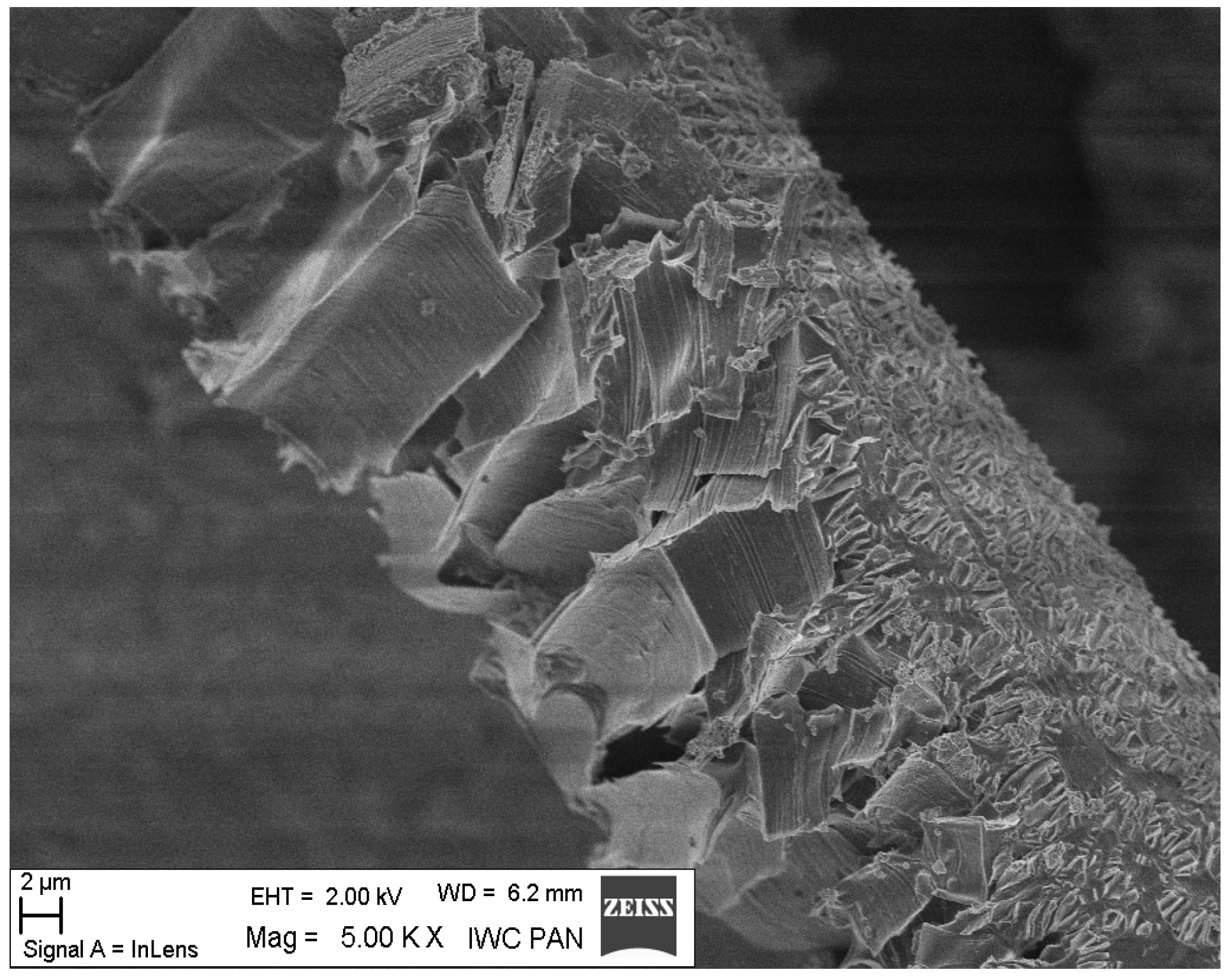

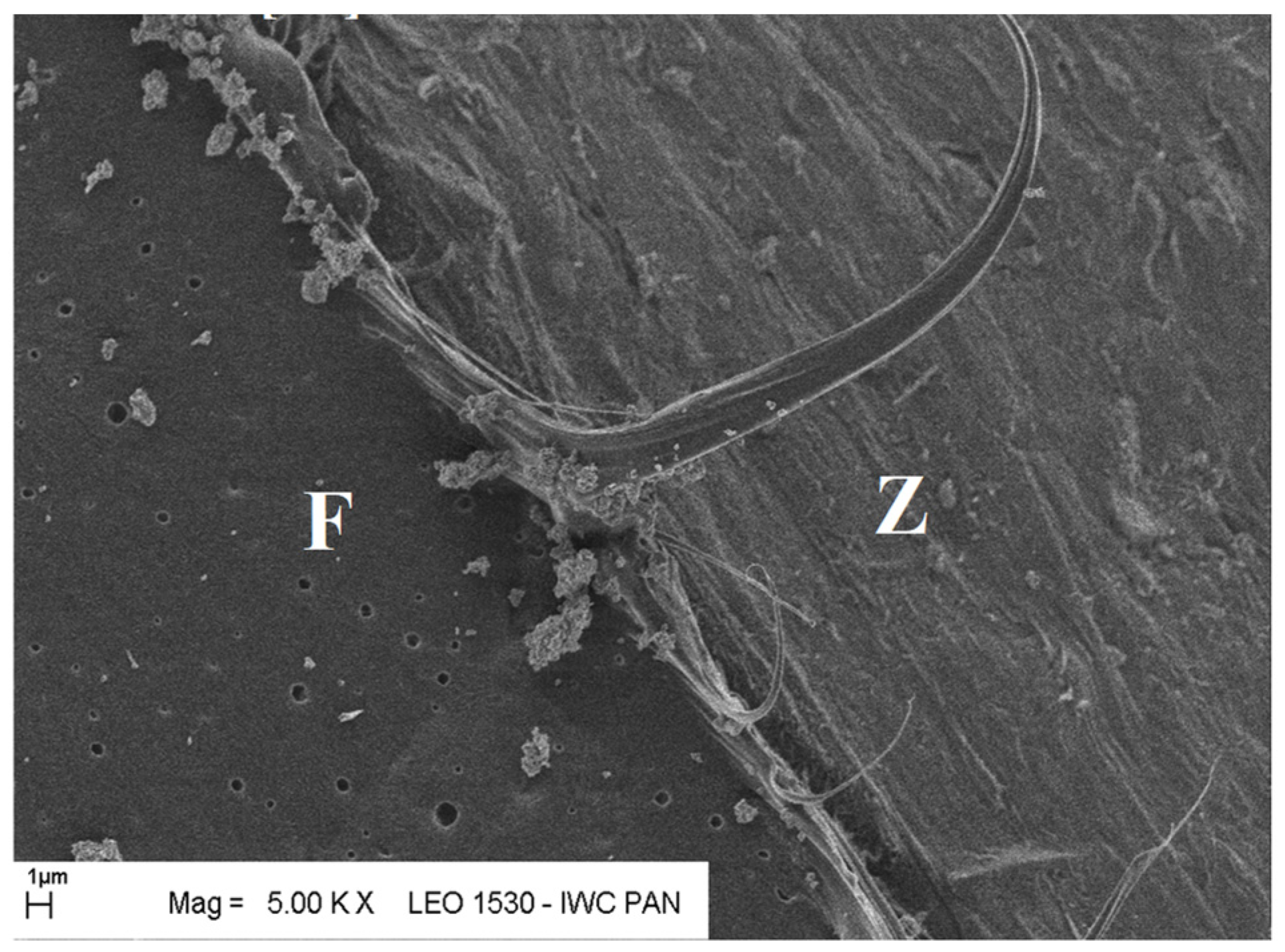

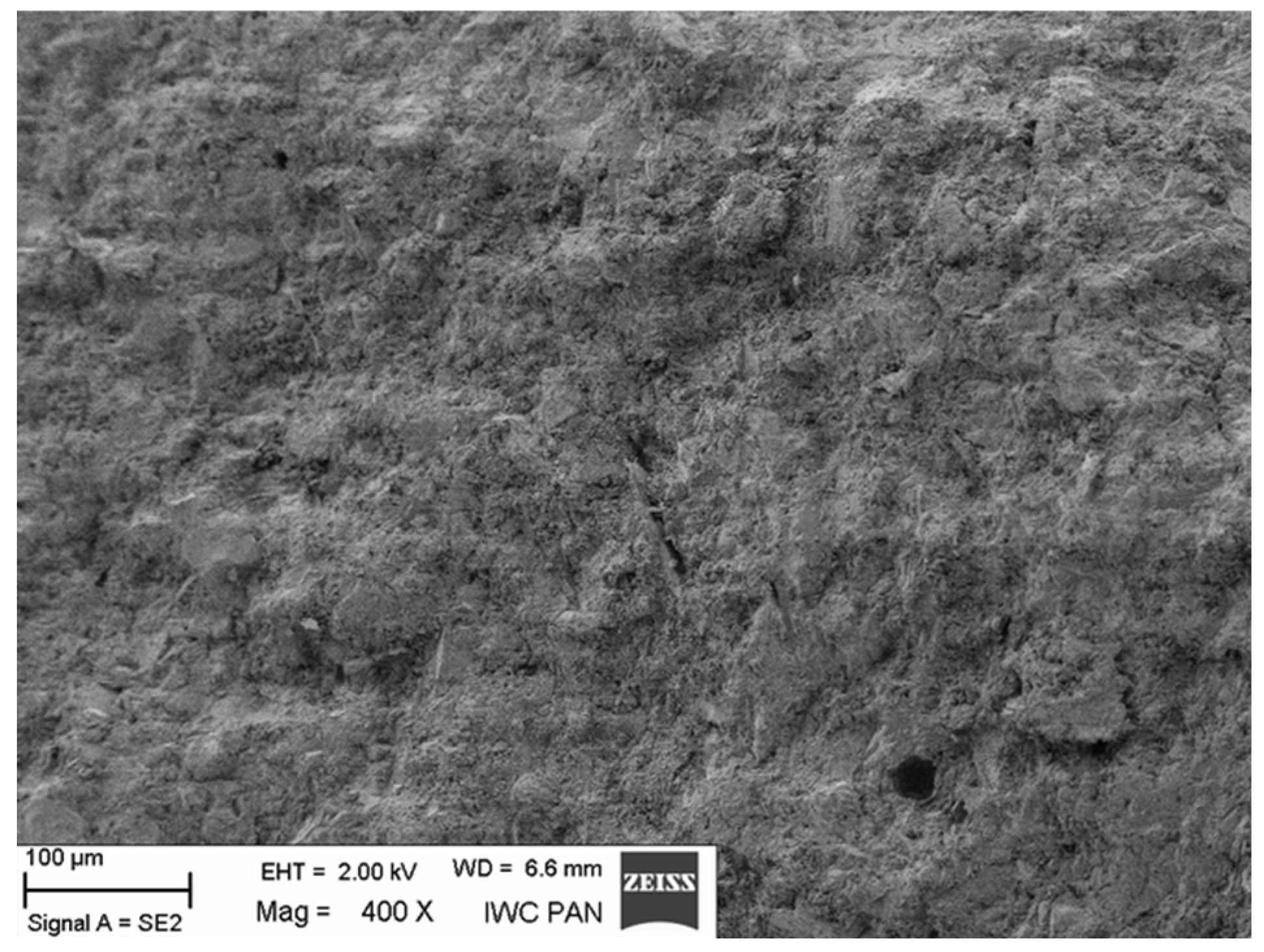

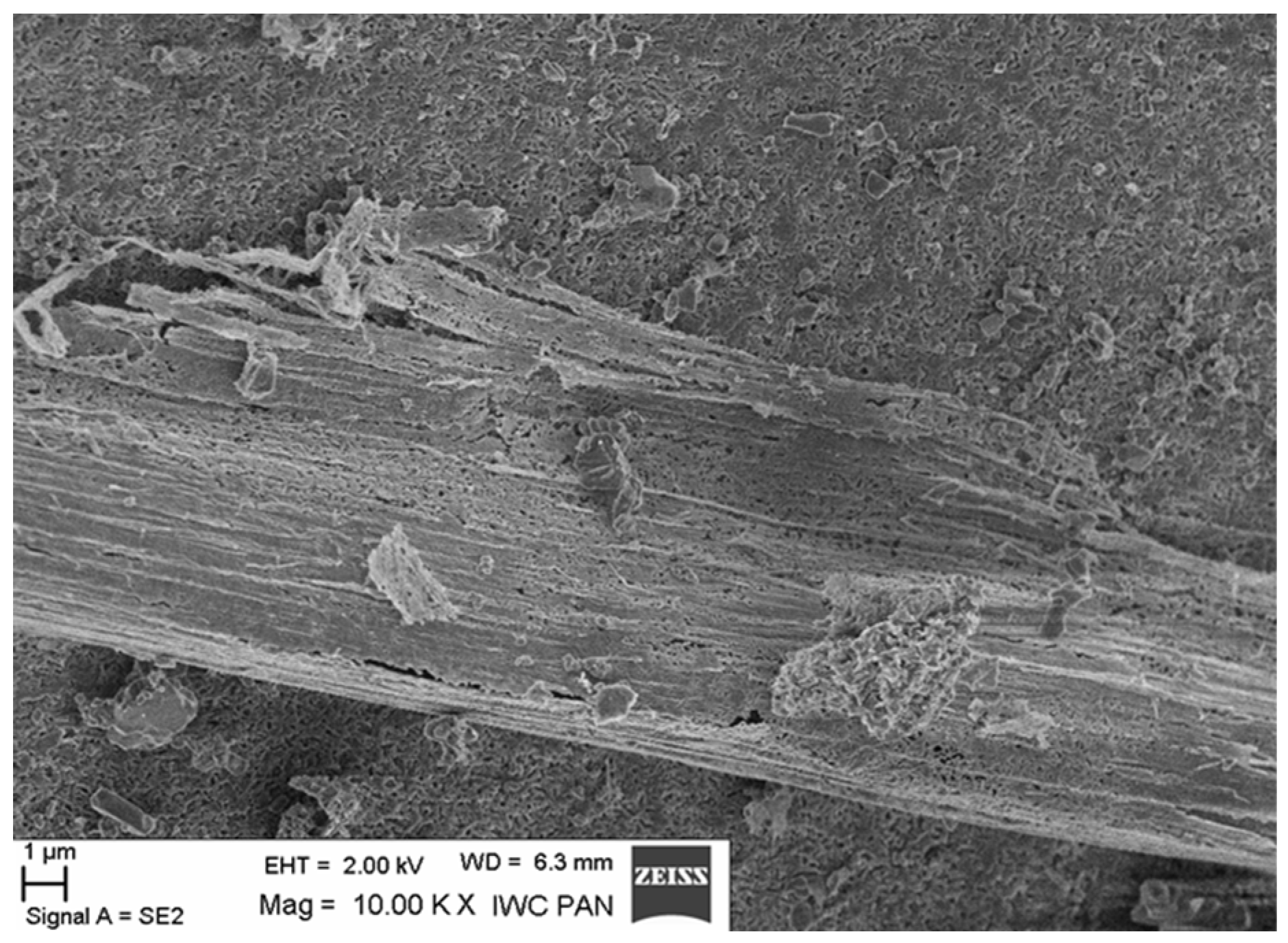

2.1. Materials

2.2. Sample Preparation

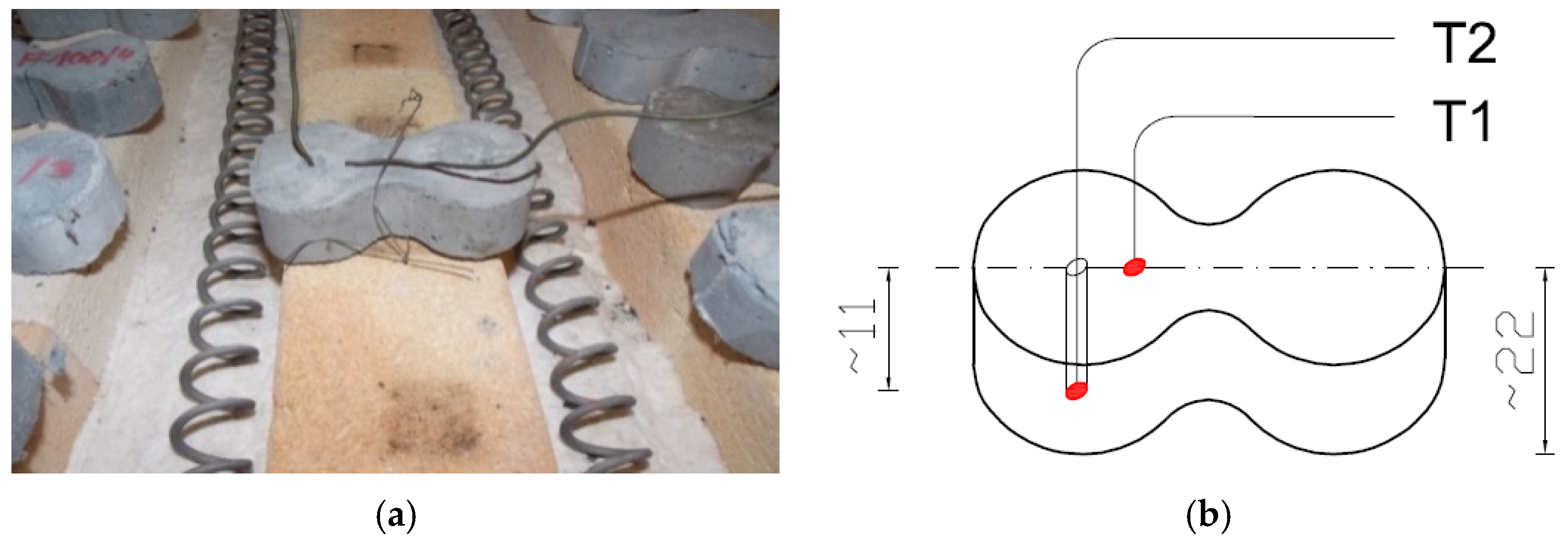

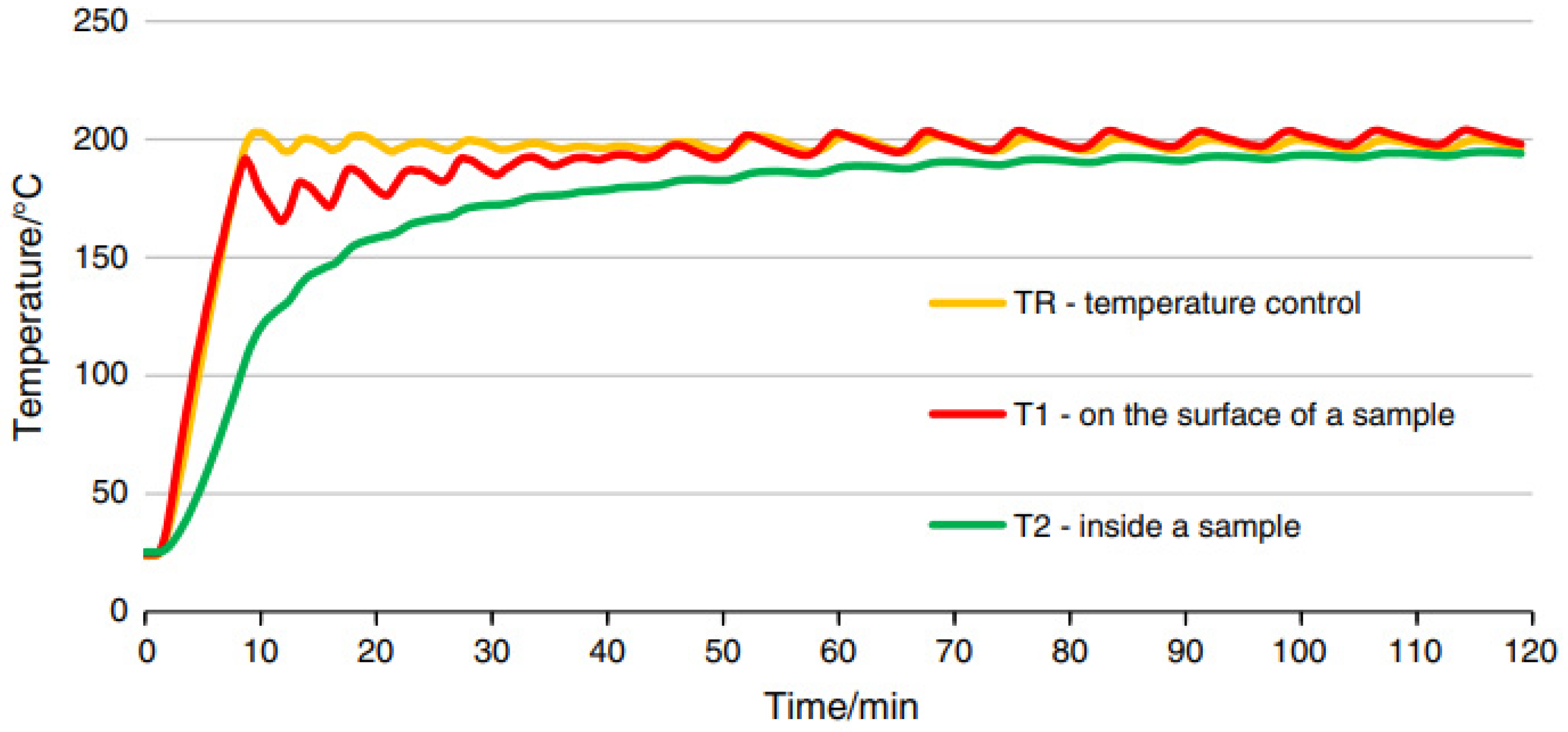

2.3. Procedure of Thermal Treatment of Samples

2.4. Thermal Analysis

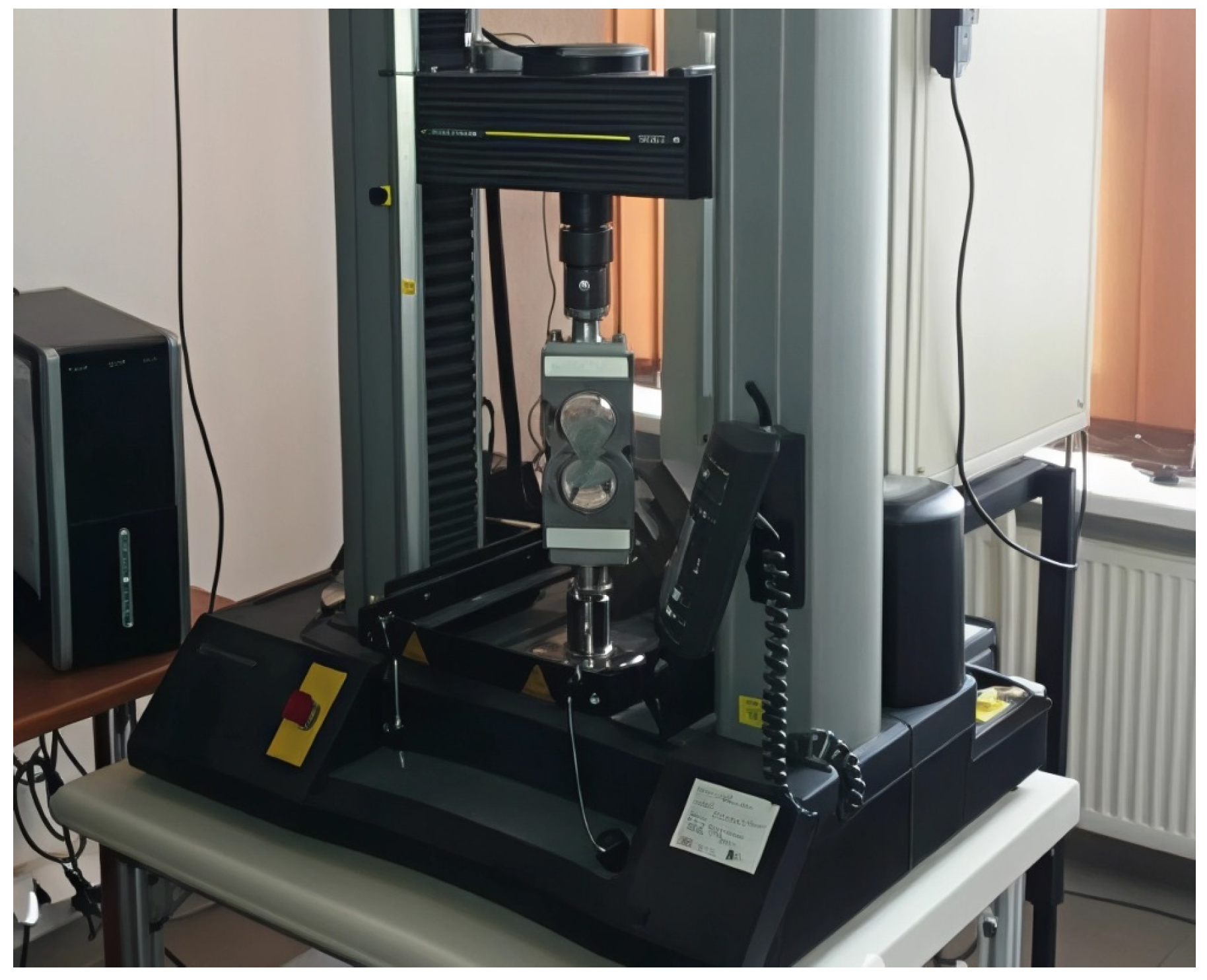

2.5. Mechanical Testing

3. Results and Discussion

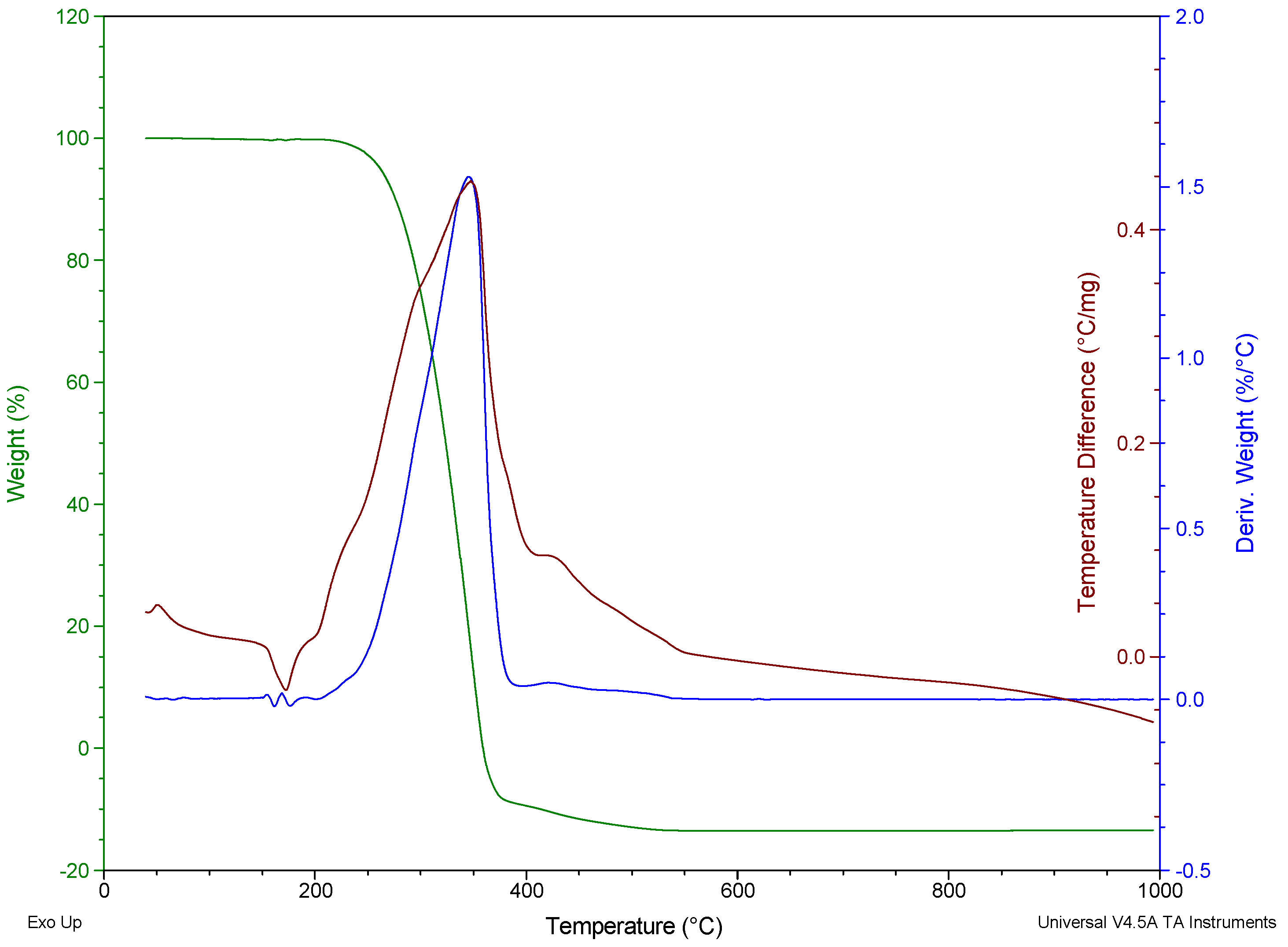

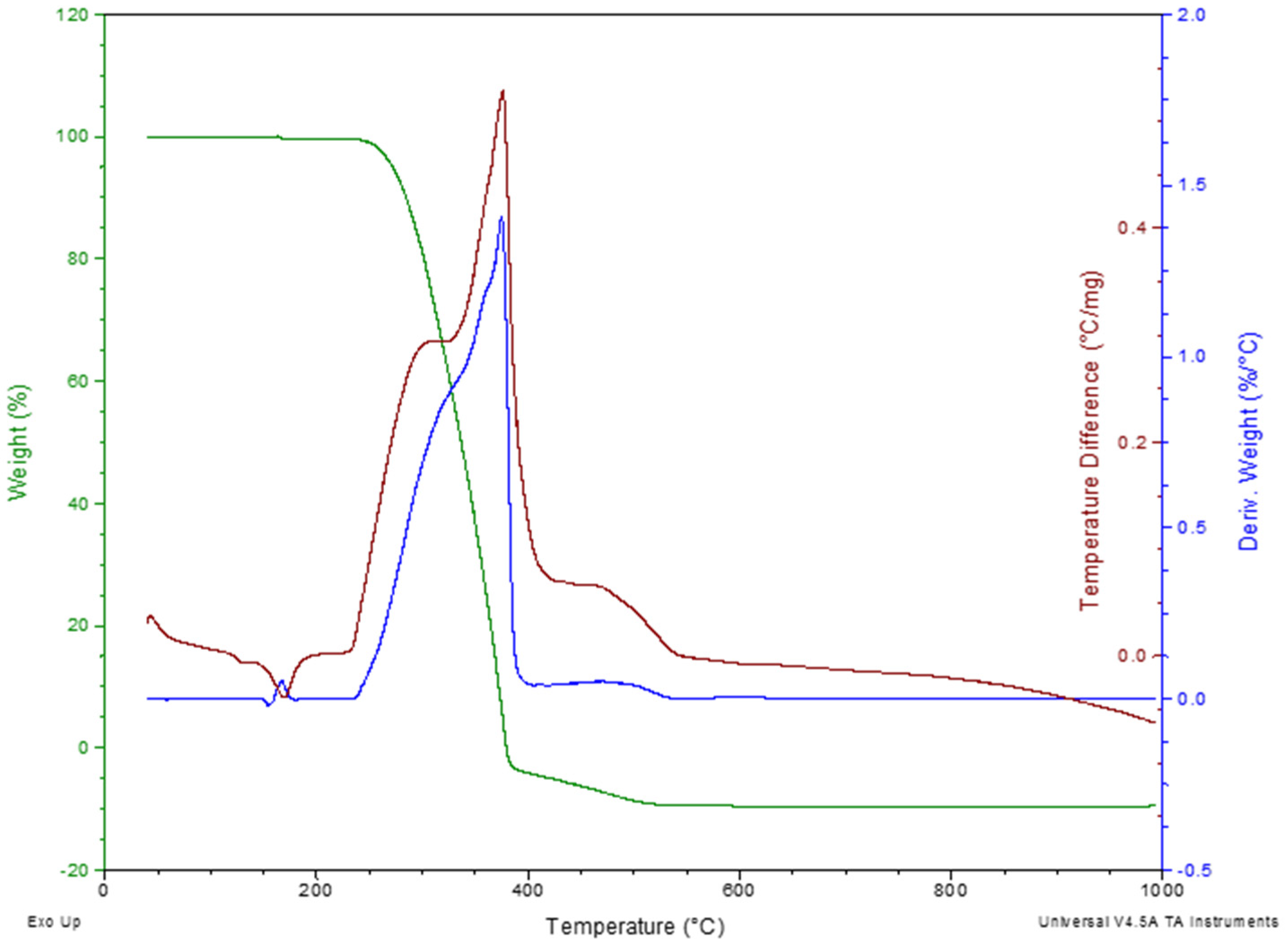

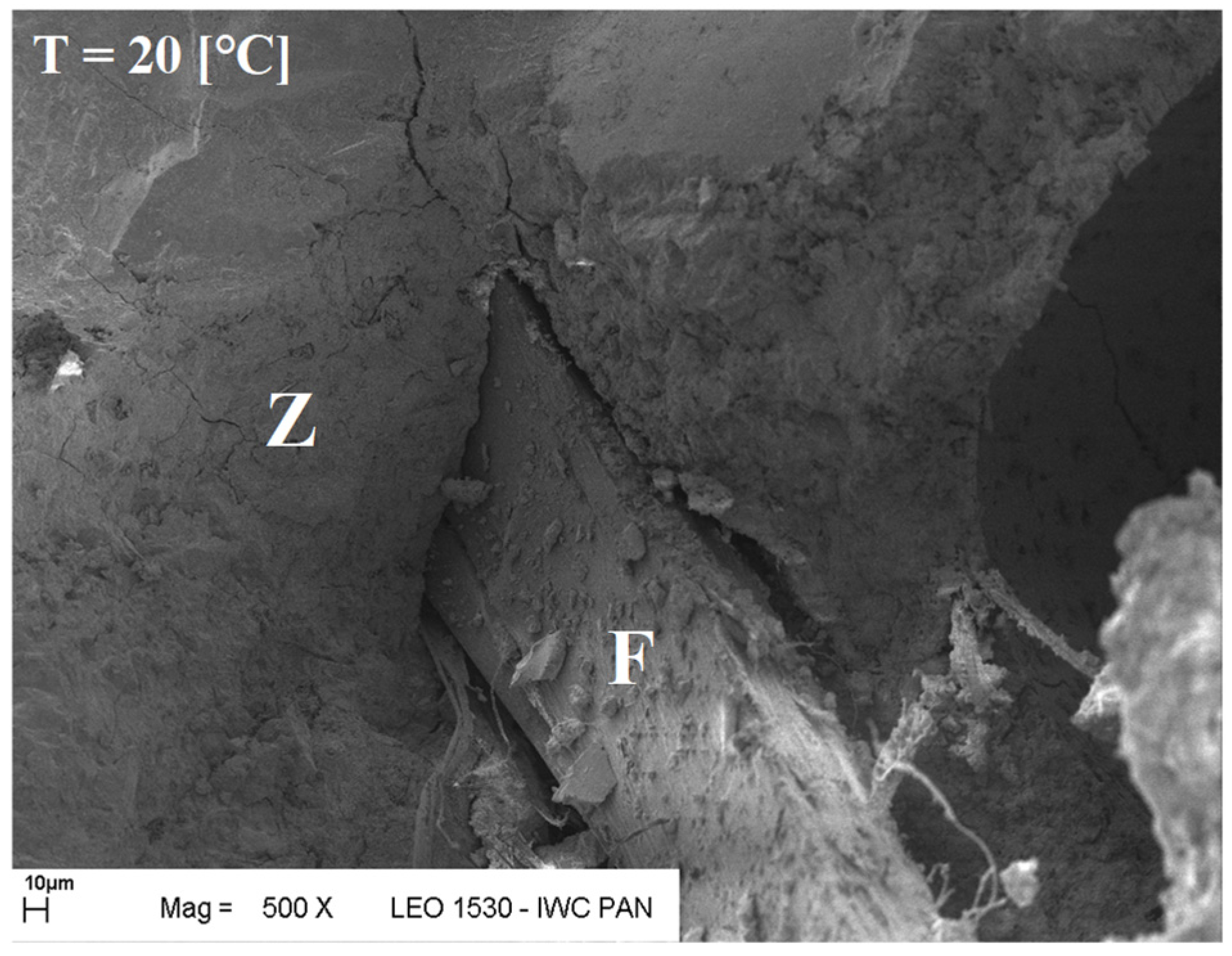

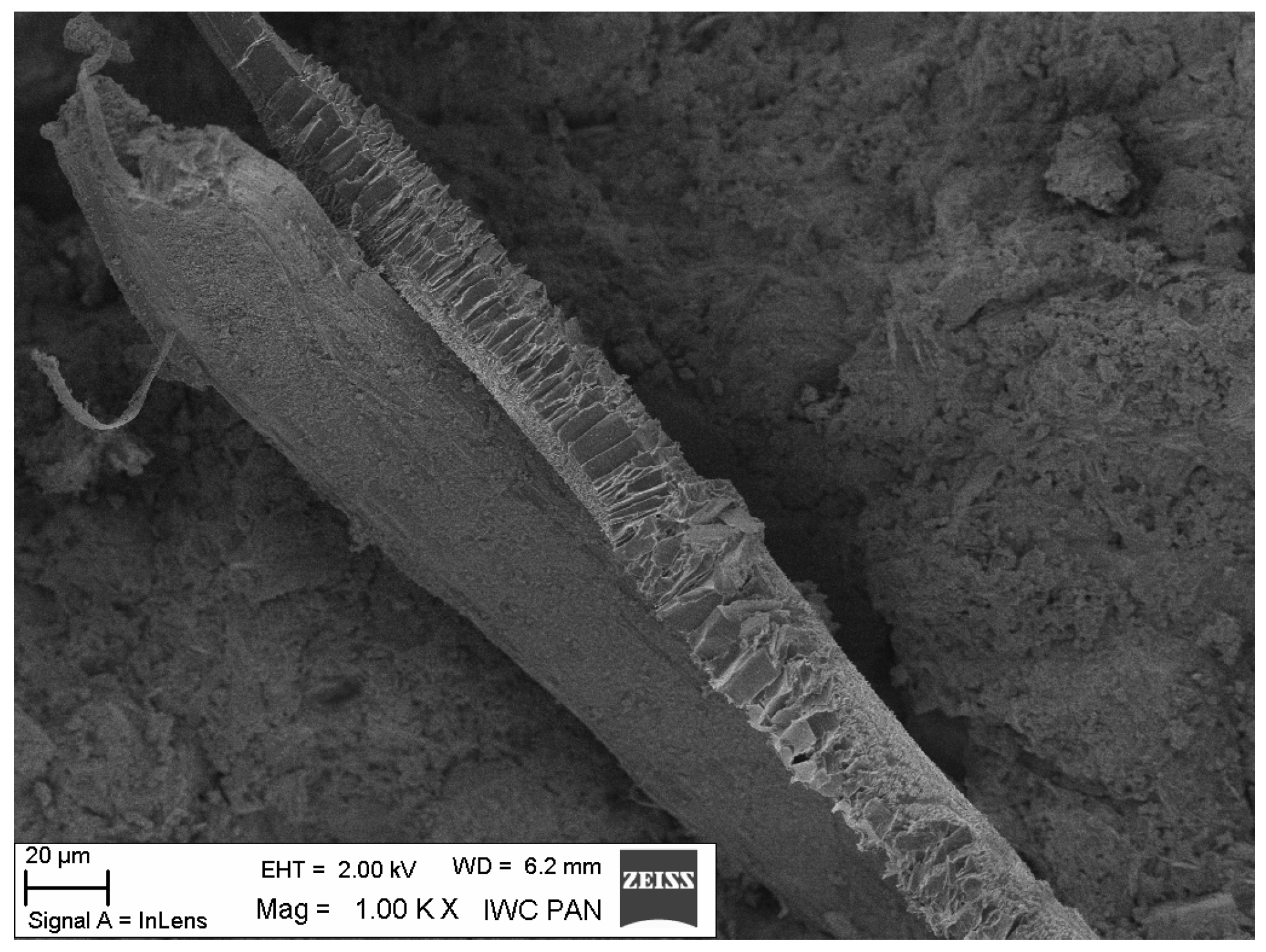

3.1. Thermal Analysis of Polypropylene Fibres

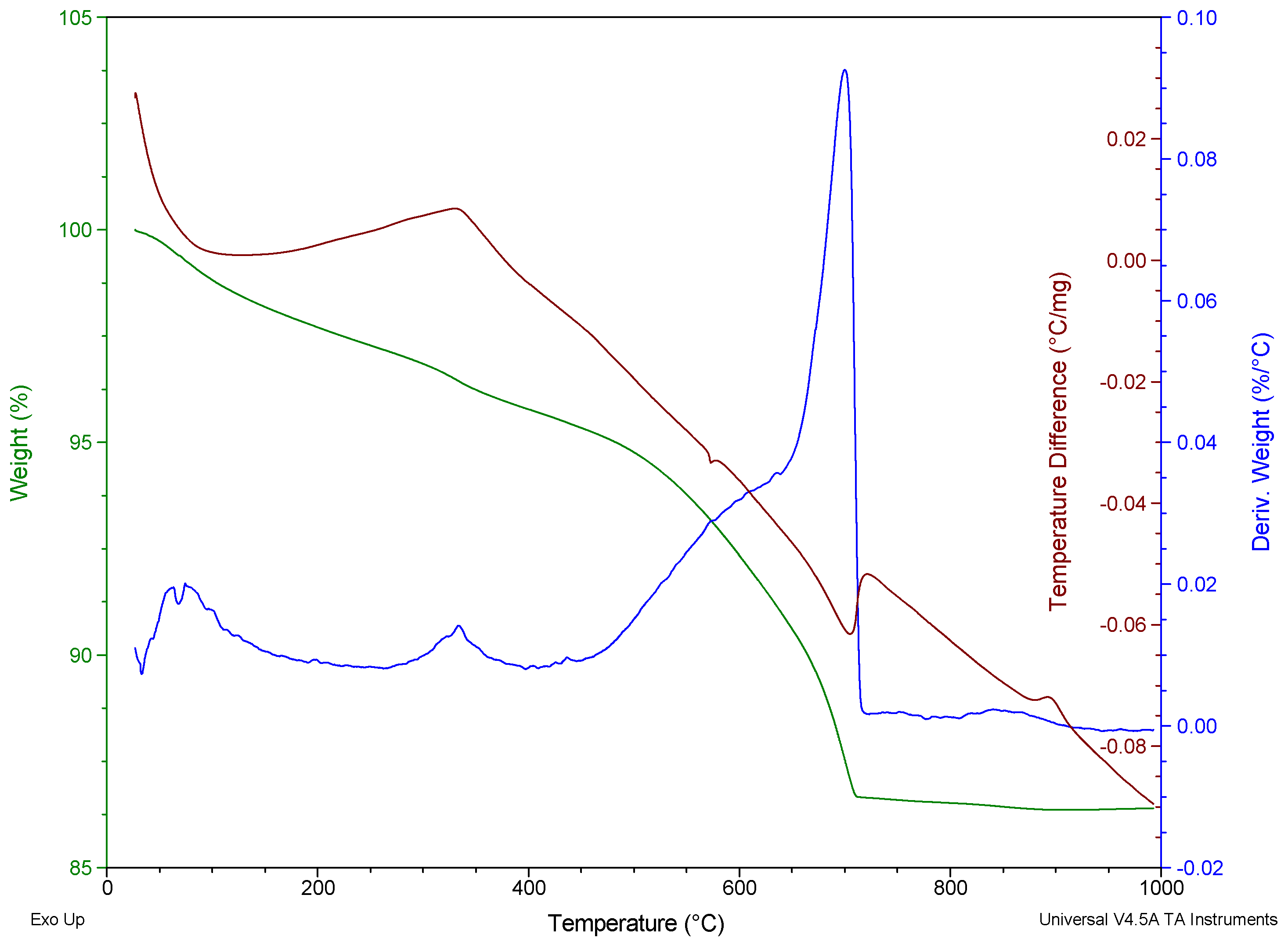

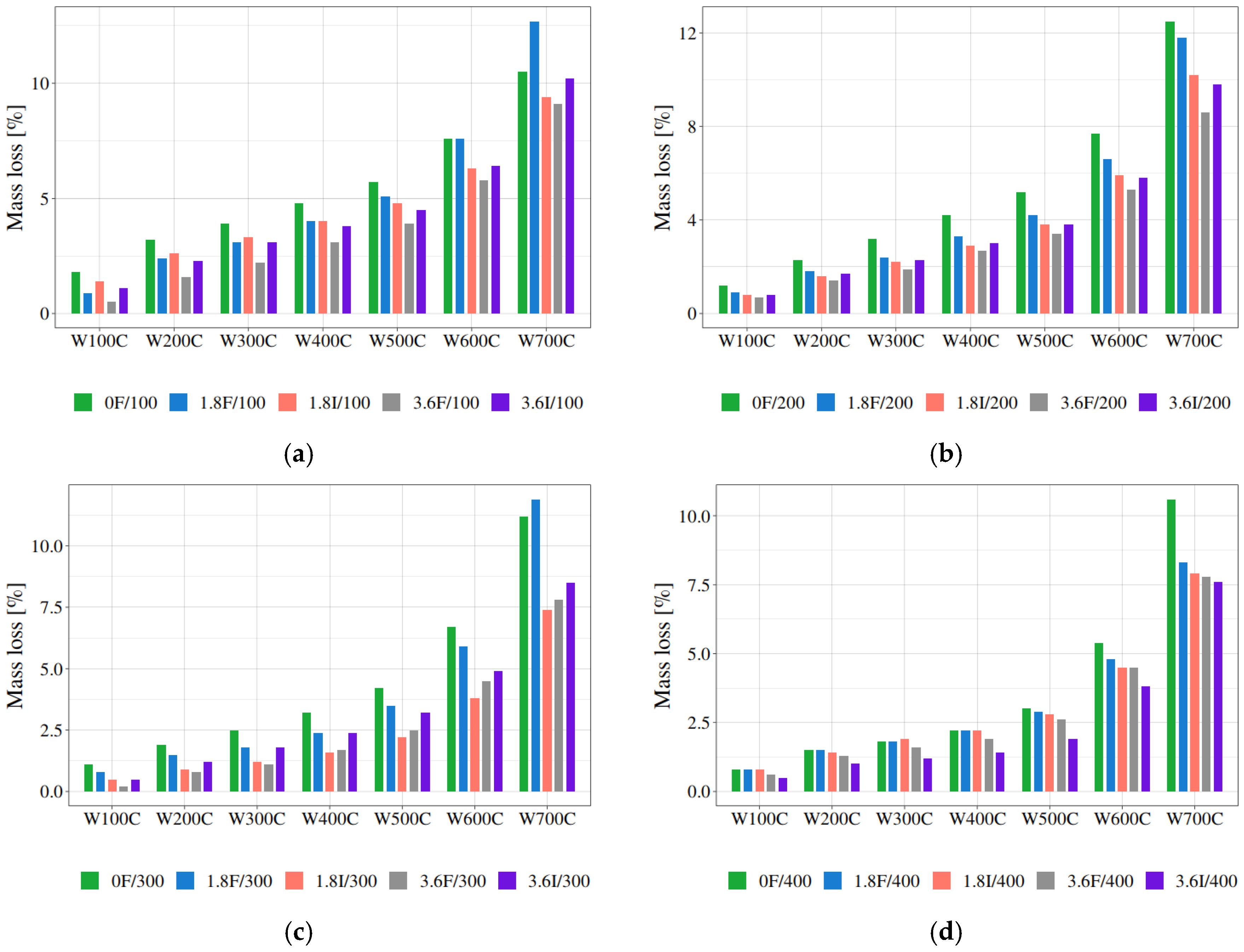

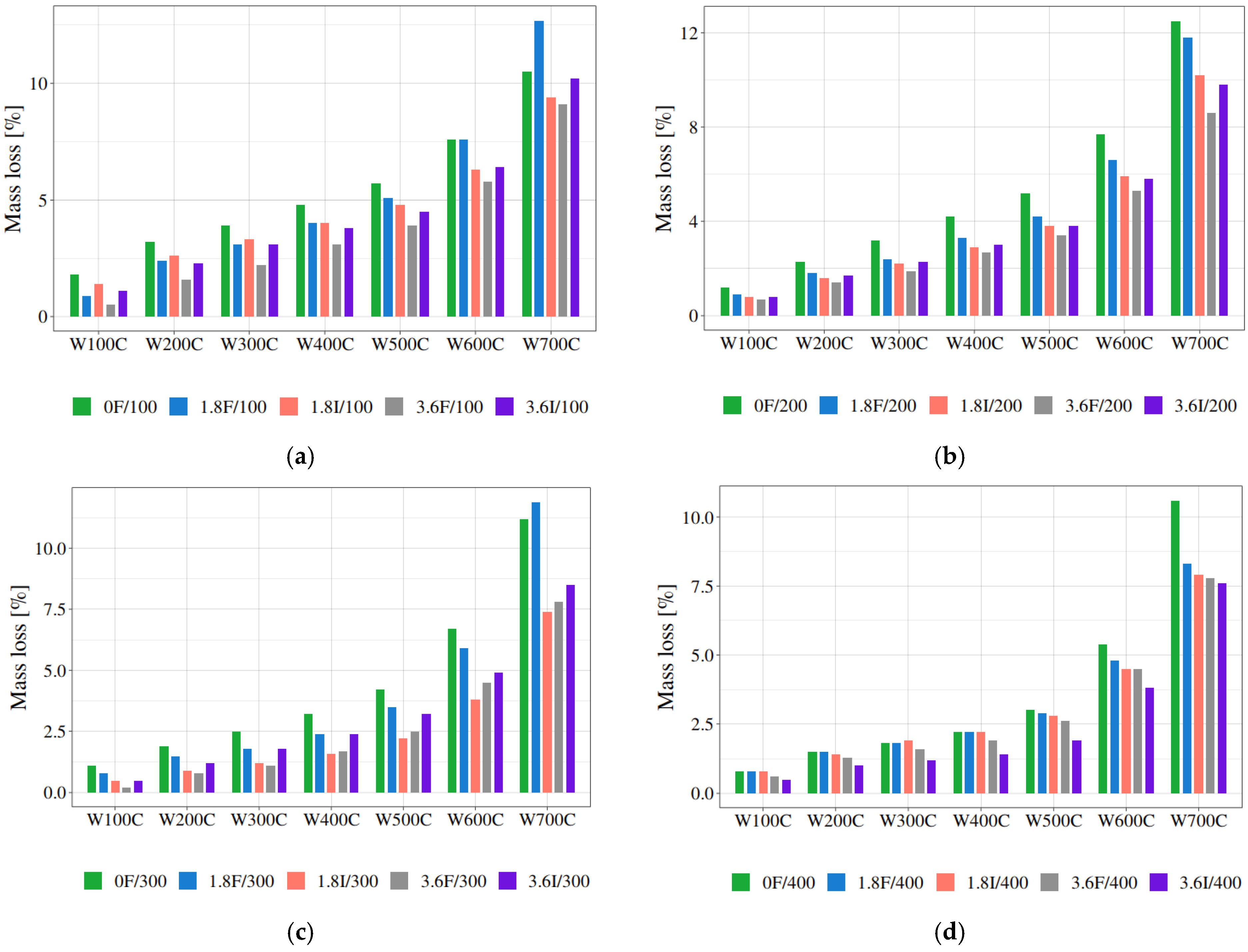

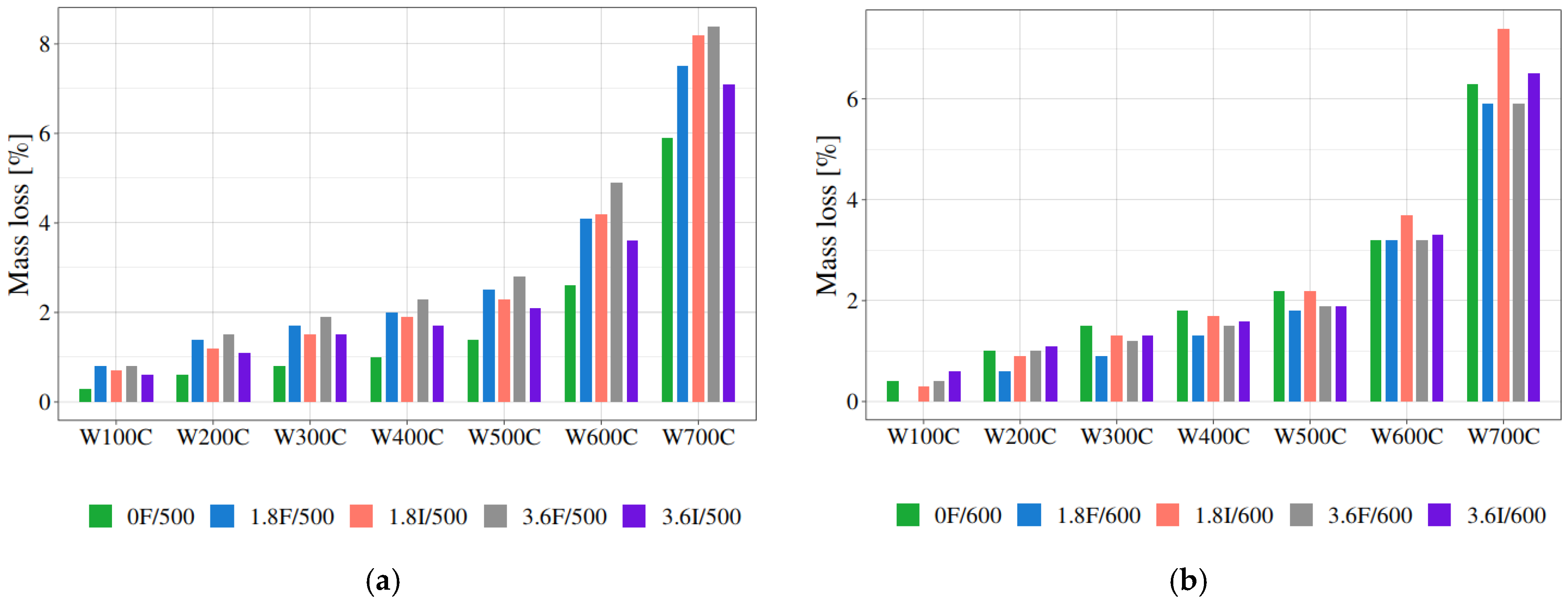

3.2. Thermal Analysis of Polypropylene Fibre-Reinforced Mortar

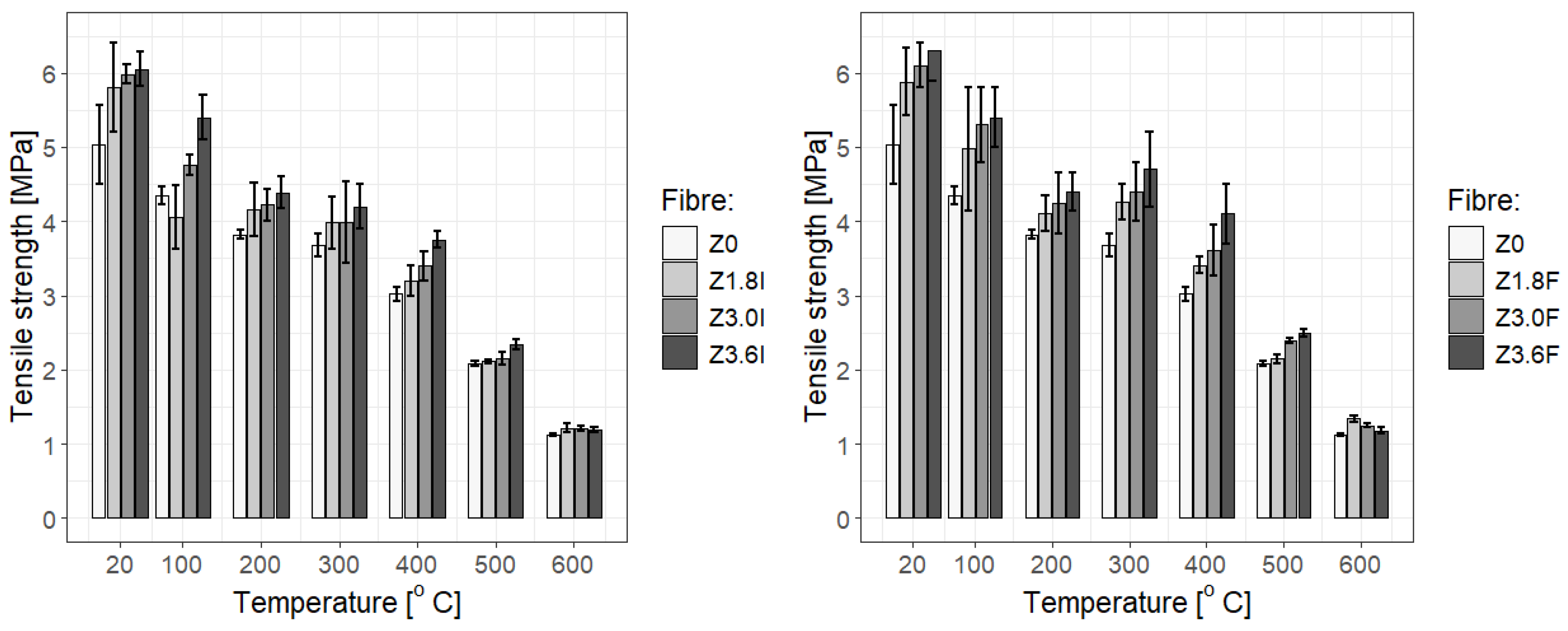

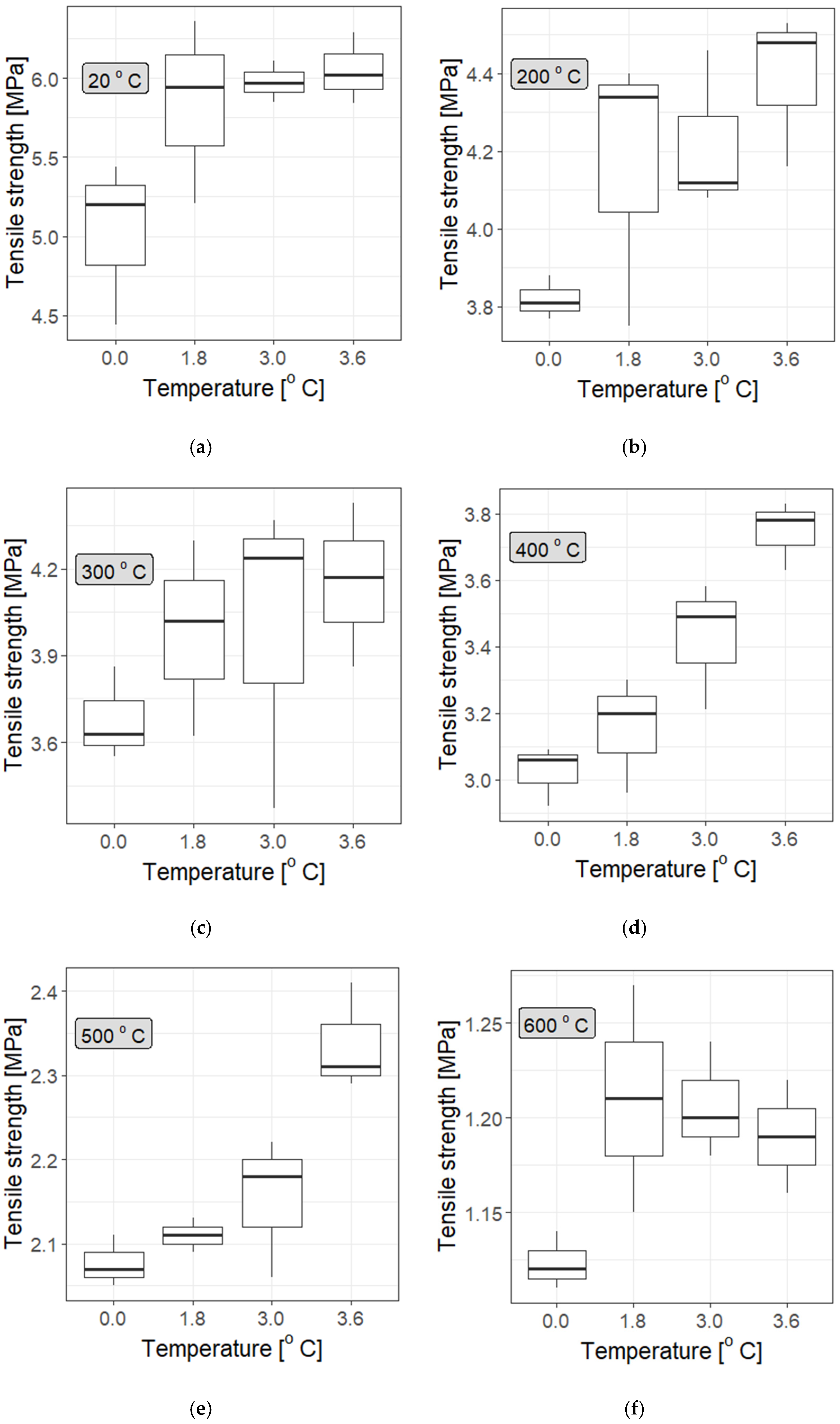

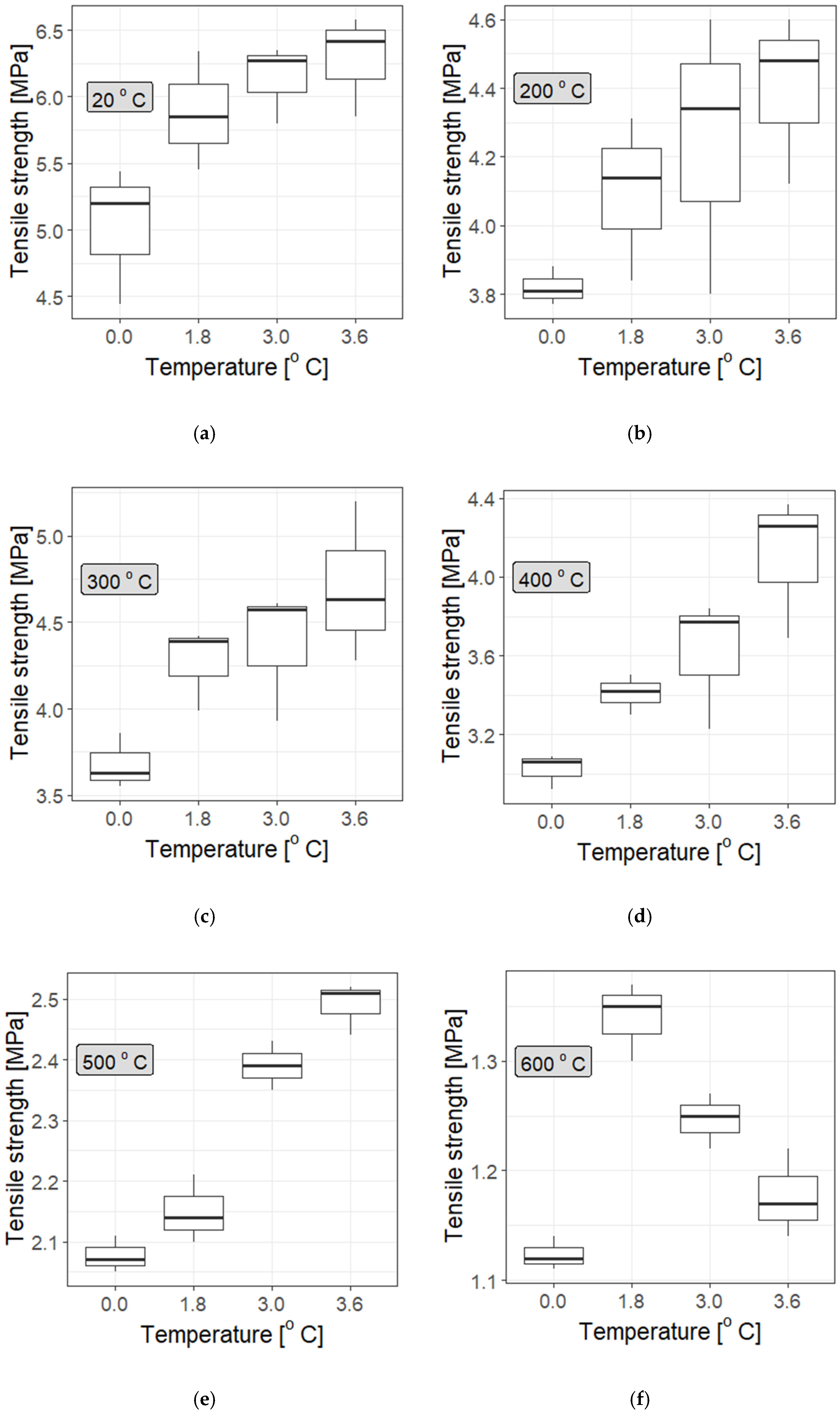

3.3. Mechanical Properties of Polypropylene Fibre-Reinforced Cement Composite (Cement Mortar)

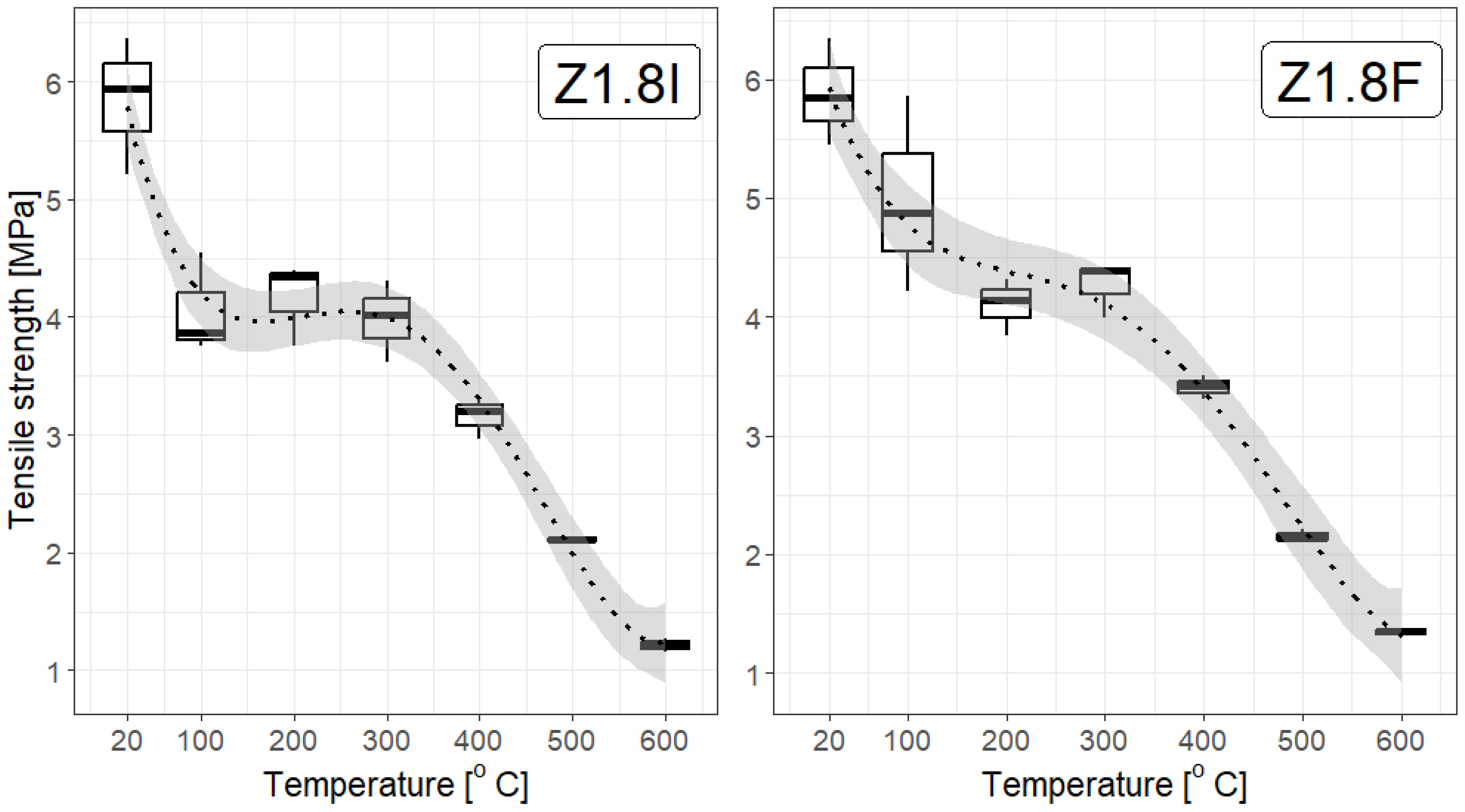

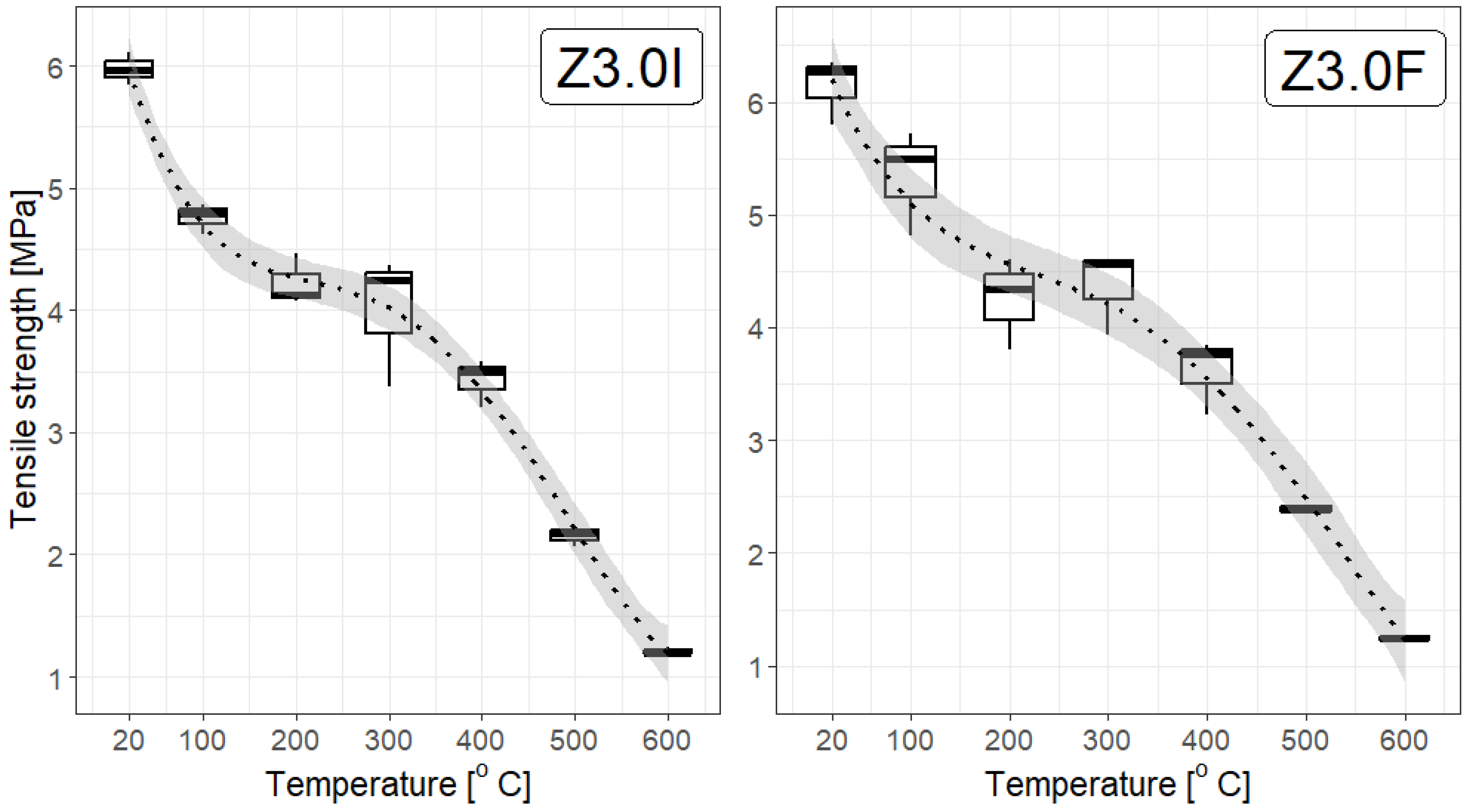

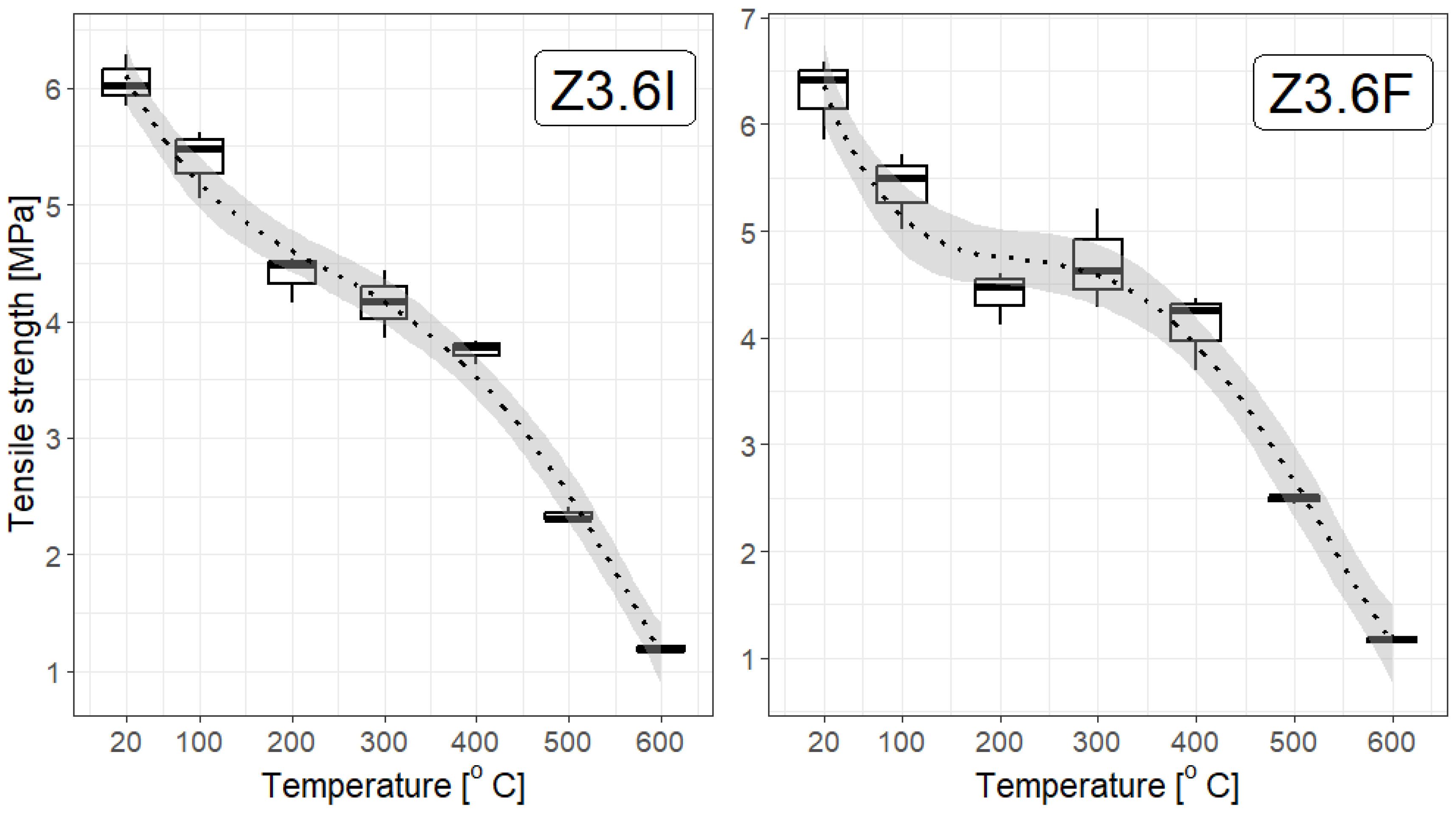

- The strength of the mortar decreases with increasing temperature, with the tensile strength at 600 °C being five-fold lower than at room temperature for all types of mortar: without polypropylene fibres, and with the addition of type I or F fibres at each of the applied concentrations;

- There is a noticeable difference between the strength of fibre-reinforced mortar (particularly at dosages of 3.0 kg/m3 and 3.6 kg/m3) and that of mortar without fibres;

- Practically, there is rather little difference in the tensile strength of the specimens depending on the fibre concentrations; at most temperatures, there does not seem to be a convincing difference among concentrations of 1.8 kg/m3, 3.0 kg/m3, and 3.6 kg/m3. However, statistical tests provide some information for mortar samples with added F fibre at 3.6 kg/m3, but not at a high confidence level (which proves that more studies should be performed). This is particularly evident at higher temperatures, which aligns with the general properties of polypropylene fibres: they soften at temperatures below 200 °C and melt above 300 °C;

- To some extent, the addition of fibres improves the mechanical properties of the mortar; however, above 500 °C all the specimens behave similarly, exhibiting a significant reduction in tensile strength (even more than five-fold). Nevertheless, within the margin of uncertainty, the strength of the specimens with added fibres is higher, although only by 5–7% for type I fibres and 5–10% for type F fibres at dosages of 3.6 kg/m3 and 3.0 kg/m3, or even up to 19% for type F fibres at a dosage of 1.8 kg/m3.

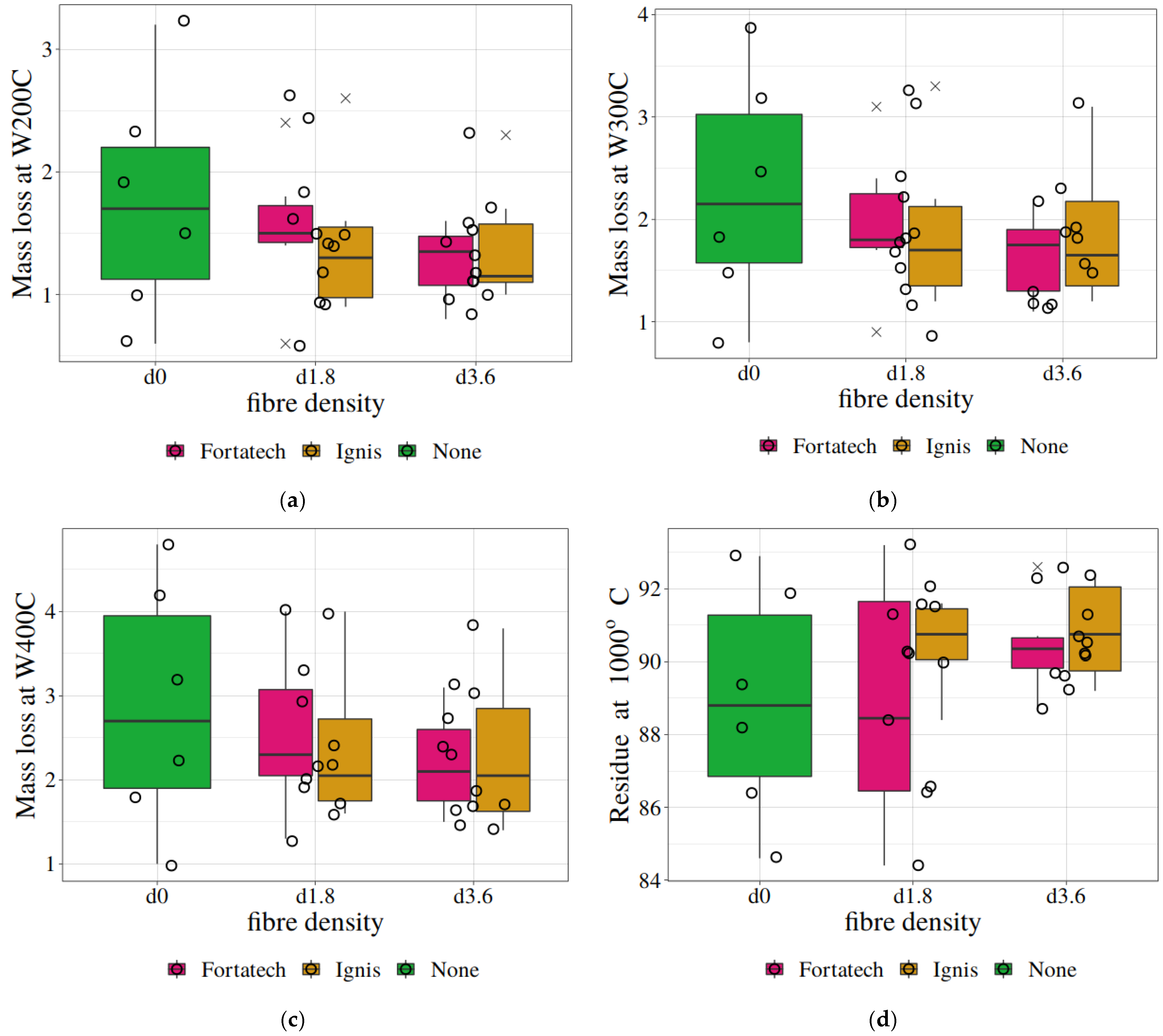

3.4. Statistical Analysis of Thermoanalytical and Mechanical Results

3.5. Statistical Analysis of Thermogravimetric Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Drzymała, T. Impact of Polypropylene Fibres on Physical and Mechanical Properties of Cement Composites at High Temperature; Scientific Monograph; Publishing House of the Main School of Fire Service: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; pp. 1–236. ISBN 978-83-950547-4-7. [Google Scholar]

- Drzymała, T.; Jackiewicz-Rek, W.; Tomaszewski, M.; Kuś, A.; Gałaj, J.; Šukys, R. Effects of High Temperature on the Properties of High Performance Concrete (HPC). Procedia Eng. 2017, 172, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drzymała, T.; Jackiewicz-Rek, W.; Gałaj, J.; Šukys, R. Assessment of mechanical properties of high strength concrete (HSC) after exposure to high temperature. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2018, 24, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawin, D.; Pesavento, F.; Schrefler, B.A. Simulation of damage-permeability coupling in hygro-thermo-mechanical analysis of concrete at high temperature. Commun. Numer. Methods Eng. 2002, 18, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawin, D.; Alonso, C.; Andrade, C.; Majorana, C.E. Effect of damage on permeability and hygro-thermal behaviour of HPCs at elevated temperatures: Part 1. Experimental results. Comput. Concr. 2005, 2, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawin, D.; Pesavento, F.; Schrefler, B.A. Towards prediction of the thermal spalling risk through a multi-phase porous media model of concrete. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2006, 195, 5707–5729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertz, K. Limits of Spalling of Fire Exposed Concrete. Fire Saf. J. 2003, 38, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalifa, P.; Menneteau, F.D.; Ouenard, D. Spalling and pore pressure in HPC at high temperatures. Cem. Concr. Res. 2000, 30, 1915–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalifa, P.; Chéné, G.; Gallé, C. High-temperature behaviour of HPC with polypropylene fibres from spalling to microstructure. Cem. Concr. Res. 2001, 31, 1487–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, G.A. Polypropylene fibres in heated concrete. Part 2: Pressure relief mechanisms and modelling criteria. Mag. Concr. Res. 2008, 60, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarek, Z.; Drzymała, T.; Szczypta, R. Safety analysis for tunnels. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference “Fire Protection 2011”, Ostrava, Czech Republic, 23–24 September 2011; pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarek, Z.; Drzymała, T. Study of the properties of fibers reinforced concrete with polypropylene fibers subjected to high temperature. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference “Fire Protection 2012”, Ostrava, Czech Republic, 5–6 September 2012; pp. 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Abramowicz, M.; Kowalski, R. Konstrukcje żelbetowe w warunkach pożaru. Przegląd Bud. 2002, 10, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Abramowicz, M.; Kowalski, R. The influence of short time water cooling on the mechanical properties of concrete heated up to high temperature. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2005, 11, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, J.-P.; Kang, H.-B.; Lee, S.-J.; Lee, S.-W.; Kang, J.-W. Thermal characteristics of high-strength polymer-cement composites with lightweight aggregates and polypropylene fibre. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 3810–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xotta, G.; Mazzucco, G.; Salomoni, V.; Majorana, C.; Wiliam, V. Composite behavior of concrete materials under high temperatures. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2015, 64, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M.; Liew, J. Mechanical behaviour of ultra-high strength concrete at elevated temperatures and fire resistance of ultra-high strength concrete filled steel tubes. Mater. Des. 2016, 104, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.; Hu, K. Development of bond strength model for CFRP-to-concrete joints at high temperatures. Compos. Part. B-Eng. 2016, 95, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Dinkha, Y.; Haido, J. Mechanical properties and spalling at elevated temperature of high performance concrete made with reactive and waste inert powders. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2017, 20, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Yu, J.; Lu, Z.; Chen, Q. Determination of the softening curve and fracture toughness of high-strength concrete exposed to high temperature. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2015, 149, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szelag, M. Analysis of the development of cluster cracks caused by elevated temperatures in cement paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 83, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szelag, M. Mechano-Physical Properties and Microstructure of Carbon Nanotube Reinforced Cement Paste after Thermal Load. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeląg, M. Wpływ Składu Kompozytów Cementowych Na Geometrię Ich Spękań Termicznych; Lublin University of Technology: Lublin, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Abyzov, V.; Radionov, A. Lightweight Refractory Concrete Based on Aluminum-Magnesium-Phosphate Binder. Procedia Eng. 2016, 150, 1440–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodur, V.; Shakya, A. Factors governing the shear response of prestressed concrete hollowcore slabs under fire conditions. Fire Saf. J. 2017, 88, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conforti, A.; Tiberti, G.; Plizzari, G.A.; Caratelli, A.; Meda, A. Precast tunnel segments reinforced by macro-synthetic fibers. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2017, 63, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawin, D.; Witek, A.; Pasavento, F. O ochronie betonowej obudowy tunelu przed zniszczeniem w warunkach pożarowych—Wyniki projektu UPTUN. Inżynieria I Bud. 2006, 62, 622–625. [Google Scholar]

- Anderberg, Y. Spalling Phenomena of HPC and OC. In Proceedings of the NIST Workshop on Fire Performance of High Strength Concrete, Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 13–14 February 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bazant, Z.P.; Kaplan, M.F. Concrete at High Temperatures. Material Properties and Mathematical Models; Longman, Harlow: Essex, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, L.T.; Carino, N.J. Mechanical Properties of High-Strength Concrete at Elevated Temperatures; NISTIR 6725; Building and Fire Research Laboratory, National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, L.T. High—Strength Concrete at High Temperature—An Overview, Utilization of High Strength Performance Concrete. In Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium Proceedings, Leipzig, Germany, 16–20 June 2002; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth, I.J. Fires in vehicular tunnels. In Proceedings of the 12th U.S./North American Mine Ventilation Symposium, Reno, NV, USA, 9–11 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ingason, H.; Li, Z.Y.; Lönnermark, A. Tunnel Fire Dynamics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gawin, D.; Pasavento, F.; Majorana, C.E.; Scherefler, B.A. Modelowanie procesu degradacji betonu w wysokich temperaturach. Inżynieria I Bud. 2003, 59, 218–221. [Google Scholar]

- Drzymała, T.; Gałaj, J. Podstawowe problemy związane z bezpieczeństwem pożarowym w budynkach mieszkalnych. Mater. Bud. 2014, 10, 178–180. [Google Scholar]

- Drzymała, T. Podstawowe problemy oraz specyfika prowadzenia działań ratowniczo-gaśniczych w tunelach drogowych. Logistyka 2014, 5, 364–370. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, P.; Ali, F.; Nadjai, A.; Choi, S. Explosive spalling of concrete columns with steel and polypropylene fibres subjected to severe fire. J. Struct. Fire Eng. 2012, 3, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Li, L. Study on mechanism of thermal spalling in concrete exposed to elevated temperatures. Mater. Struct. 2011, 44, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Tan, K.H.; Dasari, A.; Weng, Y. Effect of natural fibers on thermal spalling resistance of ultra-high performance concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 109, 103512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawin, D.; Pesavento, F.; Castells, A.G. On reliable predicting risk and nature of thermal spalling in heated concrete. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2018, 18, 1219–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.C.; Tan, K.H.; Yao, Y. A new perspective on nature of fire-induced spalling in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 184, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Tian, K. An experimental investigation of the thermal spalling of polypropylene-fibered reactive powder concrete exposed to elevated temperatures. Sci. Bull. 2015, 60, 2022–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drzymała, T. Wpływ dodatku włókien polipropylenowych do kompozytów cementowych poddanych oddziaływaniu wysokiej temperatury na ich wytrzymałość na rozciąganie. Przemysł Chem. 2017, 96, 1000–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistol, K.; Weise, F.; Meng, B. Polypropylene fibres in high performance concretes. Beton. Stahlbetonbau. 2012, 107, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnood, A.; Ghandehari, M. Comparison of compressive and splitting tensile strength of high-strength concrete with and without polypropylene fibers heated to high temperatures. Fire Saf. J. 2009, 44, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluk, C.; Bisby, L.; Terrasi, G.P. Effects of polypropylene fibre type and dose on the propensity for heat-induced concrete spalling. Eng. Struct. 2017, 141, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, J.; Kohoutkova, A. Fire response of hybrid fibre reinforced concrete to high temperature. Procedia Eng. 2017, 172, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choumanidis, D.; Badogiannis, E.; Nomikos, P.; Sofianos, A. The effect of different fibres on the flexural behaviour of concrete exposed to normal and elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 129, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czoboly, O.; Lublóy, É.; Hlavička, V.; Balázs, G.L.; Kéri, O.; Szilágyi, I.M. Fibers and fibre cocktails to improve fire resistance of concrete. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017, 128, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, M.; Sakoi, Y.; Fujimoto, K.; Tetsura, K.; Parajuli, S.S. Estimation of chloride diffusion coefficients of high-strength concrete with synthetic fibres after fire exposure. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 143, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yermak, N.; Pliya, P.; Beaucour, A.-L.; Simon, A.; Noumowe, A. Influence of steel and/or polypropylene fibres on the behaviour of concrete at high temperature: Spalling, transfer and mechanical properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 132, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-C.; Tan, K.H. Fire resistance of strain hardening cementitious composite with hybrid PVA and steel fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 135, 600–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, H.A.; Sheikh, M.N.; Hadi, M.N.S. Performance evaluation of high strength concrete and steel fibre high strength concrete columns reinforced with GFRP bars and helices. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 134, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Li, V.C. Thermal-mechanical behaviors of CFRP-ECC hybrid under elevated temperatures. Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 110, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnik, E.; Drzymała, T. Thermal behavior of polypropylene fibre-reinforced concrete at elevated temperatures. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2018, 131, 1005–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.-Y.; Sun, D.-L.; Han, Y.; Wang, J.; Xia, J.; Zhu, J.; Miao, Y.-H. Low-alkalinity activation of calcium carbide slag for blast furnace slag-based materials: Synergistic effects of carbonation curing on performance and microstructure. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 113, 114190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.-Y.; Wang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.-Y. Perforated cenospheres used to enhance the engineering performance of high-performance cement-slag-limestone ternary binder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 455, 139084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Wu, H.-N.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, G.-Y.; Zhang, F.; Mariani, S. Investigation of the microstructure, mechanical properties and thermal degradation kinetics of EPDM under thermo-stress conditions used for joint sealing of floating prefabricated concrete platform of offshore wind power. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 485, 141897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, H.M.; Neto, J.A.D.F.; Haach, V.G.; Neto, J.M. Physical and mechanical properties of cement-lime mortar for masonry at elevated temperatures: Destructive and ultrasonic testing. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 104, 112291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Miao, J.; Yu, Y.; Hou, D.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X. Non-explosive spalling UHPC mediated by synergistic regulation of thermal stress and vapor pressure. Compos. Part B Eng. 2025, 305, 112712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drzymała, T.; Zegardło, B.; Przystupa, K. Assessment of Relationship Between Temperature and Selected Technical Parameters of High-Strength, Fine-Grained Ordinary and Polypropylene Fibre-Modified Building Mortars Subjected to Conditions Simulating Fire. Materials 2025, 18, 5358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PN-EN 197-1:2012; Cement. Part 1: Composition, Requirements and Conformity Criteria for Common Cements. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2002.

- EN 1097-6:2022; Tests for Mechanical and Physical Properties of Aggregates—Part 6: Determination of Particle Density and Water Absorption. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgum, 2022.

- EN 1097-3:1999; Tests for Mechanical and Physical Properties of Aggregates—Part 3: Determination of Loose Bulk Density and Voids. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgum, 1999.

- PN-EN-ISO 10523:2012; Water Quality—Determination of pH. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2012.

- PN-EN 1008:2004; Concrete Mixing Water. Specification for Sampling, Testing, and Evaluation of Concrete Mixing Water. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2004.

- PN-EN 934-2:2010; Admixtures for Concrete, Mortar and Grout. Part 2: Admixtures for Concrete. Definitions, Requirements, Conformity, Marking and Labelling. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2010.

- PN-EN 60584-1:2014-04; Thermocouples—Part 1: Specifications and Tolerances for EMF. Polish Committee for Standardisation: Warsaw, Poland, 2014.

- PN-EN 1991-1-2; Eurocode 1: Actions on Structures, Part 1-2: Actions on Structures in Fire. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 1991.

- ISO 11357-1:2023; Plastics—Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- ISO 11358-1:2022; Plastics—Thermogravimetry (TG) of Polymers. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- PN-85 B-04500; Construction Mortars—Testing of Physical and Mechanical Properties. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 1985.

- Statistical Tools for High-Throughput Data Analysis. Available online: http://www.sthda.com/english/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Parvin, C.A. Statistical topics in the laboratory sciences. Methods Mol. Biol. 2007, 404, 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veazie, P.J. Understanding statistical testing. SAGE Open 2015, 5, 2158244014567685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyckman, T.R.; Zeff, S.A. Important Issues in Statistical Testing and Recommended Improvements in Accounting Research. Econometrics 2019, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Mishra, P.; Pandey, C.M.; Singh, U.; Sahu, C.; Keshri, A. Descriptive statistics and normality tests for statistical data. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2019, 22, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.R.; Imon, A.H.M.R. A Brief Review of Tests for Normality. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Singh, U.; Pandey, C.M.; Mishra, P.; Pandey, G. Application of Student’s t-test, Analysis of Variance, and Covariance. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2019, 22, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewick, V.; Cheek, L.; Ball, J. Statistics review 7: Correlation and regression. Crit. Care 2003, 7, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y.; Feng, Z.; Yi, X. A general introduction to adjustment for multiple comparison. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017, 9, 1725–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cousineau, D.; Chartier, S. Outliers detection and treatment: A review. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2010, 3, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackiewicz-Rek, W.; Drzymała, T.; Kuś, A.; Tomaszewski, M. Durability of high performance concrete (HPC) subject to fire temperature impact. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2016, 4, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Hwang, Y.; Yang, S.; Gowripalan, N. Performance of spalling resistance of high performance concrete with polypropylene fibre contents and lateral confinement. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 1747–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | Unit | Mean Result | Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beginning of setting | min | 233 | >60 |

| End of setting | min | 291 | |

| Water demand | % | 27.5 | |

| Volume stability | mm | 1.1 | <10 |

| Specific surface area | cm2/g | 3688 | |

| Compressive strength: after 2 days | MPa | 23.9 | <10 |

| Compressive strength: after 28 days | MPa | 55.9 | >42.5 < 62.5 |

| Chemical analysis: SO3 | % | 2.77 | <3.0 |

| Chemical analysis: Cl | % | 0.070 | <0.10 |

| Chemical analysis: Na2O eq. | % | 0.53 | <0.6 |

| Parameter | Unit | Value | Evaluation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Form | - | fine-grained powder | visual |

| Colour | - | Grey | visual |

| Odour | - | Odourless | - |

| Density | g/cm3 | 2.05 | EN 1097-6 [63] |

| Bulk density | g/cm3 | 1.1 | EN 1097-3 [64] |

| Alkalinity | pH | lower than 11.5 | PN-EN-ISO 10523 [65] |

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Form | liquid |

| Colour | light brown |

| Density | 1070 ± 20 kg/m3 |

| pH | 6.5 ± 1 |

| Contents of Cl− | ≤0.1% |

| Contents of Na2O | ≤1.5% |

| Raw material base | Polycarboxylic ethers |

| Property | Fibre Name | |

|---|---|---|

| Ignis | Fibrofor High Grade 190 | |

| Colour | Transparent | Beige |

| Characteristic | Monofilament | Bonded, fibrillated |

| Length, mm | 12 | 19 |

| Film thickness, μm | 18 | 80 |

| Density, g/cm3 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| Tensile strength, N/mm2 | min 28 cN tex−1 a | ~400 |

| Softening temperature, °C | ~165 | ~150 |

| Components | Abbreviation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0F | 1.8F | 3.0F | 3.6F | 1.8I | 3.0I | 3.6I | |

| Cement CEM I 42.5 R, kg/m3 | 846 | 846 | 846 | 846 | 846 | 846 | 846 |

| Silica, kg/m3 | 84.6 | 84.6 | 84.6 | 84.6 | 84.6 | 84.6 | 84.6 |

| Sand, kg/m3 | 1249 | 1249 | 1249 | 1249 | 1249 | 1249 | 1249 |

| Optima 185 plasticiser, % cement mass | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Water, dm3 | 215 | 215 | 215 | 215 | 215 | 215 | 215 |

| Polypropylene fibres, kg/m3 | 0 | 1.8 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 1.8 | 3.0 | 3.6 |

| Fibre | I Cycle—Heating | II Cycle—Cooling | III Cycle—Heating | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melting Temperature, °C | Melting Enthalpy, J/g | Crystallisation Temperature, °C | Crystallisation Enthalpy, J/g | Melting Temperature, °C | Melting Enthalpy, J/g | |

| I | I peak: 157.9 II peak: 171.1 | 1.8 55.0 | 119.5 | 95.7 | 161.8 | 78.8 |

| F | I peak: 126.8 II peak: 171.9 | 6.3 46.9 | 115.0 | 92.6 | I peak: 129.6 II peak: 164.0 | 11.4 57.6 |

| Fibre | T5% | T10% | DTGpeak | DTApeak1 | DTApeak2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ignis | 261.7 | 276.1 | 345.2 | 172.5 (endo) | 347.2 (exo) |

| Fibrofor | 272.0 | 284.6 | 374.9 | 169.4 (endo) | 375.9 (exo) |

| Sample | Mass Loss, W100C, % | Mass Loss, W100–450C, % | Mass Loss, W450–520C, % | Mass Loss, W600–900C, % | Residue, W1000C, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0F/20 | 0.98 | 2.6 | 0.7 | 5.1 | 89.3 |

| 1.8F/20 | 2.7 | 3.99 | 0.5 | 2.97 | 88.8 |

| 3.6F/20 | 1.5 | 3.5 | 0.9 | 5.9 | 86.5 |

| 1.8I/20 | 1.4 | 3.4 | 0.8 | 5.5 | 87.1 |

| 3.6I/20 | 1.3 | 3.1 | 0.7 | 3.9 | 89.7 |

| 0F/100 | 0.9 | 3.5 | 1.0 | 8.1 | 84.4 |

| 1.8F/100 | 1.7 | 3.4 | 0.8 | 3.1 | 89.4 |

| 3.6F/100 | 0.5 | 2.9 | 0.8 | 5.5 | 88.7 |

| 1.8I/100 | 1.4 | 3.0 | 0.6 | 3.7 | 89.9 |

| 3.6I/100 | 1.1 | 3.0 | 0.7 | 4.1 | 89.6 |

| 0F/200 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 0.9 | 7.0 | 86.4 |

| 1.8F/200 | 1.2 | 3.5 | 0.9 | 6.0 | 86.4 |

| 3.6F/200 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 5.1 | 89.7 |

| 1.8I/200 | 0.7 | 2.4 | 0.8 | 5.7 | 88.4 |

| 3.6I/200 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 0.6 | 4.9 | 90.2 |

| 0F/300 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 7.5 | 86.6 |

| 1.8F/300 | 1.0 | 2.6 | 1.0 | 5.1 | 88.2 |

| 3.6F/300 | 0.2 | 1.8 | 0.7 | 5.3 | 90.2 |

| 1.8I/300 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 4.6 | 91.6 |

| 0F/400 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 10.0 | 84.6 |

| 1.8F/400 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 4.9 | 90.3 |

| 3.6F/400 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 4.8 | 90.7 |

| 1.8I/400 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 4.2 | 91.3 |

| 3.6I/400 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 5.0 | 91.3 |

| 0F/500 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 5.6 | 91.9 |

| 1.8F/500 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 3.7 | 92.1 |

| 3.6F/500 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 4.7 | 90.5 |

| 1.8I/500 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 5.1 | 90.6 |

| 3.6I/500 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 4.1 | 92.3 |

| 0F/600 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 3.9 | 92.9 |

| 1.8F/600 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 3.6 | 93.2 |

| 3.6F600 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 4.2 | 92.6 |

| 1.8I/600 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 4.9 | 91.5 |

| 3.6I/600 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 4.4 | 92.1 |

| Sample | Mass Loss, W100C, % | Mass Loss, W200C, % | Mass Loss, W300C, % | Mass Loss, W400C, % | Mass Loss, W500C, % | Mass Loss, W600C, % | Mass Loss, W700C, % | Residue at 1000 °C, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0F/100 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 3.1 | 4.0 | 5.1 | 7.6 | 12.7 | 84.4 |

| 1.8F/100 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 3.9 | 4.8 | 5.7 | 7.6 | 10.5 | 89.4 |

| 3.6F/100 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 3.1 | 3.9 | 5.8 | 9.1 | 88.7 |

| 1.8I/100 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 3.3 | 4.0 | 4.8 | 6.3 | 9.4 | 90.0 |

| 3.6I/100 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 3.8 | 4.5 | 6.4 | 10.2 | 89.6 |

| 0F/200 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 3.3 | 4.2 | 6.6 | 11.8 | 86.4 |

| 1.8F/200 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 2.2 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 5.1 | 8.3 | 91.3 |

| 3.6F/200 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 5.3 | 8.6 | 89.7 |

| 1.8I/200 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 2.9 | 3.8 | 5.9 | 10.2 | 88.4 |

| 3.6I/200 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 3.8 | 5.8 | 9.8 | 89.2 |

| 0F/300 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 3.5 | 5.9 | 11.9 | 86.6 |

| 1.8F/300 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 4.2 | 6.7 | 11.2 | 88.2 |

| 3.6F/300 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 2.5 | 4.5 | 7.8 | 90.2 |

| 1.8I/300 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 3.8 | 7.4 | 91.6 |

| 3.6I/300 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 4.9 | 8.5 | 90.2 |

| 0F/400 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 3.0 | 5.4 | 10.6 | 84.6 |

| 1.8F/400 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 2.9 | 4.8 | 8.3 | 90.3 |

| 3.6F/400 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 4.5 | 7.8 | 90.7 |

| 1.8I/400 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 4.5 | 7.9 | 91.3 |

| 3.6I/400 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 3.8 | 7.6 | 91.3 |

| 0F/500 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 5.9 | 91.9 |

| 1.8F/500 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 4.1 | 7.5 | 92.1 |

| 3.6F/500 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 4.9 | 8.4 | 90.5 |

| 1.8I/500 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 3.7 | 7.5 | 91.3 |

| 3.6I/500 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 3.6 | 7.1 | 92.3 |

| 0F/600 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 3.2 | 6.3 | 92.9 |

| 1.8F/600 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 5.9 | 93.2 |

| 3.6F/600 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 3.2 | 5.9 | 92.6 |

| 1.8I/600 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 3.7 | 7.4 | 91.5 |

| 3.6I/600 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 3.3 | 6.5 | 92.4 |

| Temperature, °C | Tensile Strength ftm, MPa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples with No Fibres | Samples with Fibres Ignis “I” | Samples with Fibrofor “F” Fibres | |||||

| 0.0 kg/m3 | 1.8 kg/m3 | 3.0 kg/m3 | 3.6 kg/m3 | 1.8 kg/m3 | 3.0 kg/m3 | 3.6 kg/m3 | |

| 20 °C | 4.44 | 6.36 | 5.97 | 5.84 | 6.34 | 6.27 | 5.85 |

| 5.44 | 5.94 | 6.11 | 6.29 | 5.45 | 6.35 | 6.42 | |

| 5.20 | 5.21 | 5.85 | 6.02 | 5.85 | 5.80 | 6.58 | |

| mean ftm, ± std.er., MPa | 5.03 ± 0.30 | 5.84 ± 0.34 | 5.98 ± 0.08 | 6.05 ± 0.13 | 5.88 ± 0.26 | 6.14 ± 0.18 | 6.28 ± 0.23 |

| 100 °C | 4.21 | 3.75 | 4.86 | 5.05 | 5.86 | 5.49 | 5.01 |

| 4.38 | 4.54 | 4.62 | 5.62 | 4.88 | 4.81 | 5.50 | |

| 4.43 | 3.87 | 4.79 | 5.48 | 4.21 | 5.72 | 5.72 | |

| mean ftm, ± std.er., MPa | 4.34 ± 0.07 | 4.05 ± 0.25 | 4.76 ± 0.07 | 5.38 ± 0.18 | 4.98 ± 0.48 | 5.34 ± 0.28 | 5.41 ± 0.21 |

| 200 °C | 3.81 | 4.40 | 4.12 | 4.48 | 4.31 | 4.60 | 4.12 |

| 3.77 | 4.34 | 4.46 | 4.53 | 4.14 | 4.34 | 4.48 | |

| 3.88 | 3.75 | 4.08 | 4.16 | 3.84 | 3.80 | 4.60 | |

| mean ftm, ± std.er., MPa | 3.82 ± 0.04 | 4.16 ± 0.22 | 4.22 ± 0.12 | 4.39 ± 0.12 | 4.10 ± 0.14 | 4.25 ± 0.24 | 4.40 ± 0.15 |

| 300 °C | 3.86 | 3.62 | 4.24 | 3.86 | 4.39 | 3.93 | 5.20 |

| 3.55 | 4.02 | 4.37 | 4.43 | 4.42 | 4.61 | 4.63 | |

| 3.63 | 4.30 | 3.37 | 4.17 | 3.99 | 4.57 | 4.28 | |

| mean ftm, ± std.er., MPa | 3.68 ± 0.10 | 3.98 ± 0.20 | 3.99 ± 0.32 | 4.15 ± 0.17 | 4.27 ± 0.14 | 4.37 ± 0.22 | 4.70 ± 0.27 |

| 400 °C | 3.06 | 3.20 | 3.58 | 3.78 | 3.50 | 3.23 | 4.37 |

| 2.92 | 2.96 | 3.21 | 3.83 | 3.42 | 3.77 | 4.26 | |

| 3.09 | 3.30 | 3.49 | 3.63 | 3.30 | 3.84 | 3.69 | |

| mean ftm, ± std.er., MPa | 3.02 ± 0.06 | 3.15 ± 0.10 | 3.43 ± 0.12 | 3.75 ± 0.06 | 3.41 ± 0.06 | 3.61 ± 0.20 | 4.11 ± 0.22 |

| 500 °C | 2.11 | 2.09 | 2.18 | 2.31 | 2.10 | 2.43 | 2.52 |

| 2.07 | 2.13 | 2.22 | 2.41 | 2.14 | 2.35 | 2.44 | |

| 2.05 | 2.11 | 2.06 | 2.29 | 2.21 | 2.39 | 2.51 | |

| mean ftm, ± std.er., MPa | 2.08 ± 0.02 | 2.11 ± 0.02 | 2.15 ± 0.05 | 2.34 ± 0.04 | 2.15 ± 0.04 | 2.39 ± 0.03 | 2.49 ± 0.03 |

| 600 °C | 1.14 | 1.27 | 1.18 | 1.19 | 1.37 | 1.27 | 1.22 |

| 1.11 | 1.15 | 1.20 | 1.16 | 1.30 | 1.25 | 1.14 | |

| 1.12 | 1.21 | 1.24 | 1.22 | 1.35 | 1.22 | 1.17 | |

| mean ftm, ± std.er., MPa | 1.12 ± 0.01 | 1.21 ± 0.04 | 1.21 ± 0.02 | 1.19 ± 0.02 | 1.34 ± 0.02 | 1.25 ± 0.02 | 1.18 ± 0.03 |

| Density, kg/m3 | Temperature, °C | p-Value for F | p-Value for I |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.8 | 20 | 0.79 | 0.88 |

| 100 | ~1 | 0.98 | |

| 200 | 0.69 | 0.85 | |

| 300 | 0.18 | ~1 | |

| 400 | 0.15 | 0.36 | |

| 500 | 0.82 | ~1 | |

| 600 | 0.011 | 0.24 | |

| 3.0 | 20 | 0.28 | 0.25 |

| 100 | 0.22 | 0.23 | |

| 200 | 0.73 | 0.34 | |

| 300 | 0.47 | ~1 | |

| 400 | 0.33 | 0.08 | |

| 500 | 0.009 | 0.60 | |

| 600 | 0.028 | 0.21 | |

| 3.6 | 20 | 0.04 | 0.10 |

| 100 | 0.04 | 0.04 | |

| 200 | 0.15 | 0.18 | |

| 300 | 0.11 | 0.32 | |

| 400 | 0.14 | 0.06 | |

| 500 | 0.011 | 0.074 | |

| 600 | 0.21 | 0.17 |

| Null Hypothesis | p-Value for x = F | p-Value for x = I |

|---|---|---|

| Z1.8x < Z0 | 0.003 | 0.247 |

| Z3.0x < Z0 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Z3.6x < Z0 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Z3.0x < Z1.8x | 0.266 | 0.249 |

| Z3.6x < Z1.8x | 0.027 | 0.006 |

| Z3.6x < Z3.0x | 0.380 | 0.018 |

| Temperature, °C | p-Value for F ≤ I | Variance F vs. I |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | 0.12 | 0.70 |

| 100 | 0.026 | 0.78 |

| 200 | 0.54 | 0.78 |

| 300 | 0.038 | 0.34 |

| 400 | 0.016 | 0.22 |

| 500 | 0.003 | 0.16 |

| 600 | 0.032 | 0.10 |

| Mean | Median | Std. Error | Shapiro–Wilk p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W100C | d0 | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.16 | 0.917 > α |

| d1.8 | 0.68 | 0.80 | 0.11 | 0.063 > α | |

| d3.6 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.07 | 0.705 > α | |

| W200C | d0 | 1.66 | 1.50 | 0.24 | 0.659 > α |

| d1.8 | 1.47 | 1.50 | 0.26 | 0.939 > α | |

| d3.6 | 1.33 | 1.25 | 0.12 | 0.283 > α | |

| W300C | d0 | 2.17 | 1.90 | 0.30 | 0.601 > α |

| d1.8 | 1.90 | 1.80 | 0.32 | 0.914 > α | |

| d3.6 | 1.76 | 1.70 | 0.17 | 0.222 > α | |

| W400C | d0 | 2.74 | 2.20 | 0.36 | 0.324 > α |

| d1.8 | 2.45 | 2.30 | 0.44 | 0.956 > α | |

| d3.6 | 2.26 | 2.10 | 0.22 | 0.246 > α | |

| W500C | d0 | 3.23 | 3.25 | 0.55 | 0.995 > α |

| d1.8 | 3.46 | 2.90 | 0.41 | 0.312 > α | |

| d3.6 | 2.88 | 2.70 | 0.26 | 0.276 > α | |

| W600C | d0 | 5.22 | 5.65 | 0.80 | 0.611 > α |

| d1.8 | 5.30 | 4.80 | 0.50 | 0.313 > α | |

| d3.6 | 4.67 | 4.70 | 0.30 | 0.667 > α | |

| W700C | d0 | 9.9 | 11.2 | 1.3 | 0.080 > α |

| d1.8 | 8.93 | 8.30 | 0.60 | 0.714 > α | |

| d3.6 | 8.11 | 8.10 | 0.37 | 0.992 > α | |

| RES.AT 1000 °C | d0 | 87.8 | 86.5 | 1.5 | 0.116 > α |

| d1.8 | 90.22 | 90.30 | 0.61 | 0.885 > α | |

| d3.6 | 90.62 | 90.35 | 0.37 | 0.444 > α | |

| Temperature in TG Studies/H0 | Density | d0 | d1.8 |

|---|---|---|---|

| W100C H0: mass loss within the group in column is greater | d1.8 | 0.17 | -- |

| d3.6 | 0.13 | 0.22 | |

| W200C H0: mass loss within the group in column is greater | d1.8 | 0.18 | -- |

| d3.6 | 0.09 | 0.25 | |

| W300C H0: mass loss within the group in column is greater | d1.8 | 0.19 | -- |

| d3.6 | 0.10 | 0.27 | |

| W400C H0: mass loss within the group in column is greater | d1.8 | 0.24 | -- |

| d3.6 | 0.12 | 0.28 | |

| W500C H0: mass loss within the group in column is greater | d1.8 | 0.29 | -- |

| d3.6 | 0.11 | 0.22 | |

| W600C H0: mass loss within the group in column is greater | d1.8 | 0.37 | -- |

| d3.6 | 0.15 | 0.21 | |

| W700C H0: mass loss within the group in column is greater | d1.8 | 0.58 | -- |

| d3.6 | 0.23 | 0.24 | |

| Residue at 1000 °C H0: residue within the group in column is less | d1.8 | 0.73 | -- |

| d3.6 | 0.39 | 0.21 |

| Temperature Pre-Treatment | 1.8F vs. d0 | 3.6F vs. d0 | 1.8I vs. d0 | 3.6I vs. d0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 °C | 0.44 0.56 | 0.17 0.83 | 0.31 0.69 | 0.30 0.70 |

| 200 °C | 0.34 0.66 | 0.17 0.83 | 0.24 0.76 | 0.24 0.76 |

| 300 °C | 0.20 0.80 | 0.15 0.85 | 0.13 0.87 | 0.24 0.76 |

| 400 °C | 0.29 0.71 | 0.32 0.68 | 0.36 0.64 | 0.22 0.78 |

| 500 °C | 0.80 0.20 | 0.87 0.13 | -- -- | 0.72 0.28 |

| 600 °C | 0.36 0.64 | 0.43 0.57 | 0.56 0.44 | 0.49 0.51 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Drzymała, T.; Rudnik, E.; Lewicka, S. Thermoanalytical and Tensile Strength Studies of Polypropylene Fibre-Reinforced Cement Composites Designed for Tunnel Applications. Materials 2026, 19, 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010142

Drzymała T, Rudnik E, Lewicka S. Thermoanalytical and Tensile Strength Studies of Polypropylene Fibre-Reinforced Cement Composites Designed for Tunnel Applications. Materials. 2026; 19(1):142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010142

Chicago/Turabian StyleDrzymała, Tomasz, Ewa Rudnik, and Sylwia Lewicka. 2026. "Thermoanalytical and Tensile Strength Studies of Polypropylene Fibre-Reinforced Cement Composites Designed for Tunnel Applications" Materials 19, no. 1: 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010142

APA StyleDrzymała, T., Rudnik, E., & Lewicka, S. (2026). Thermoanalytical and Tensile Strength Studies of Polypropylene Fibre-Reinforced Cement Composites Designed for Tunnel Applications. Materials, 19(1), 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010142