Continuous Filament Fabrication Technology and Its Mechanical Properties for Thin-Walled Component

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

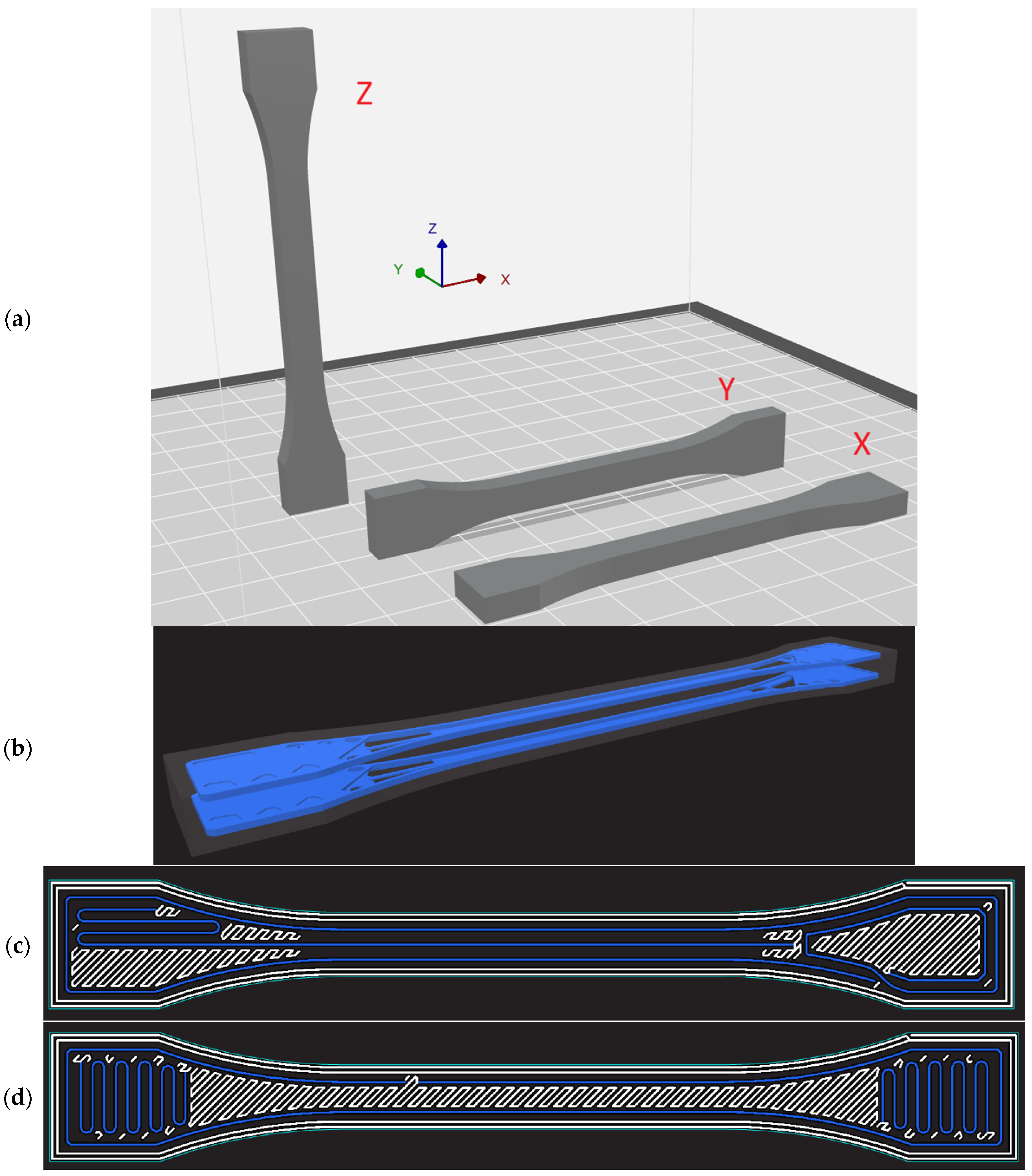

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. CFF Technology

2.2.2. Tensile Test

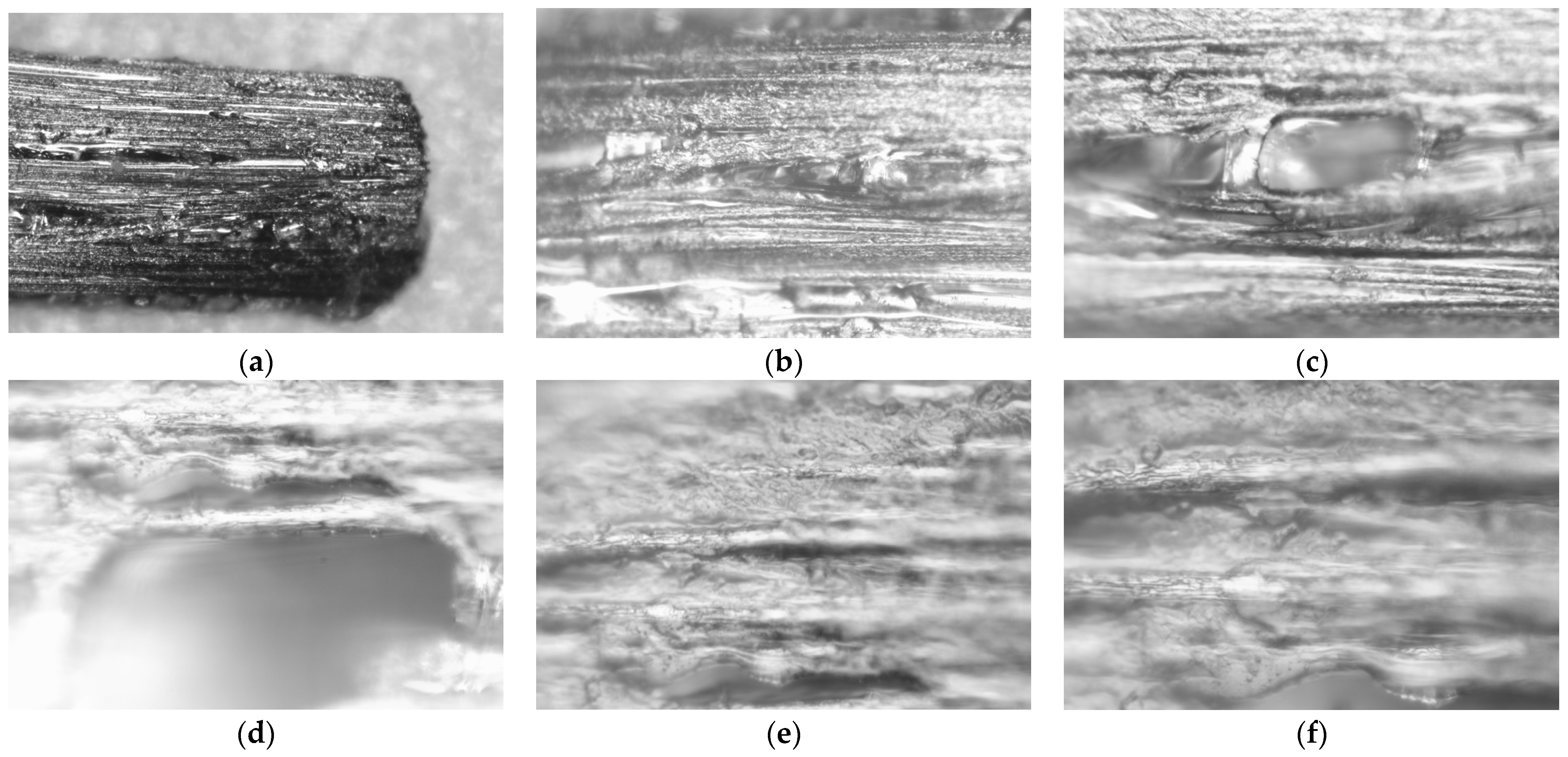

2.2.3. Microscopy Analysis

2.2.4. Dimensional Measurement

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Dimensional Accuracy

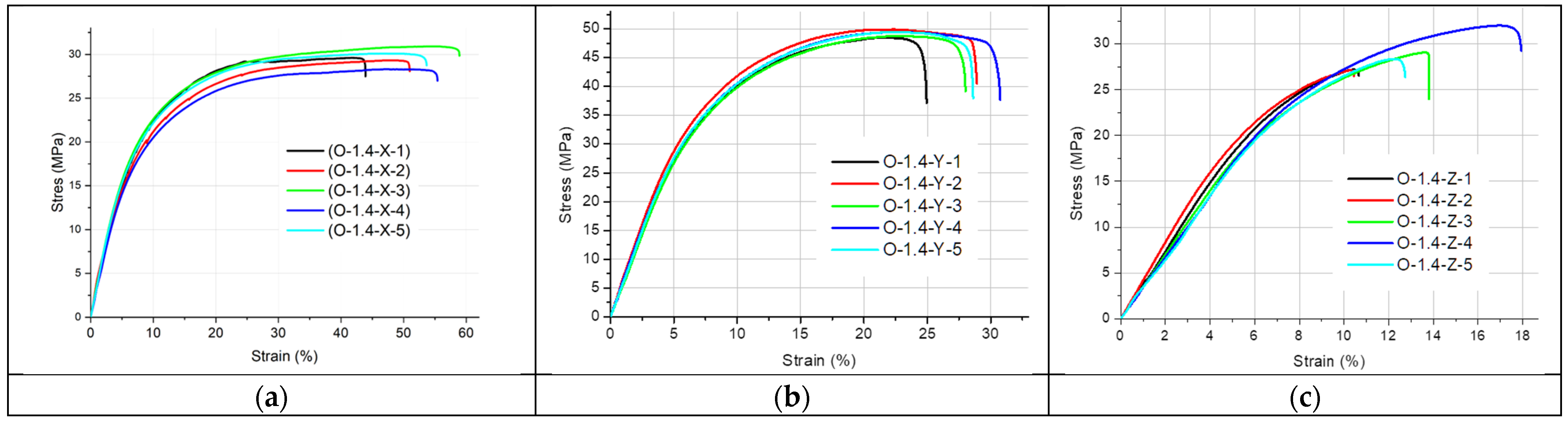

3.2. Tensile Test Results

- -

- The sample dimensions do not match the dimensions of the CAD model,

- -

- The tensile strength and strain at break, as well as other mechanical property indices, depend on the printing direction, i.e., orientation on the build platform (anisotropy).

3.3. Microscopic Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fan, H.; Liu, C.; Bian, S.; Ma, C.; Huang, J.; Liu, X.; Doyle, M.; Lu, T.; Chow, E.; Chen, L.; et al. New Era towards Autonomous Additive Manufacturing: A Review of Recent Trends and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2025, 7, 032006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.-P.; Nguyen, H.S.; Hajnys, J.; Mesicek, J.; Pagac, M.; Petru, J. A Bibliometric Review on Application of Machine Learning in Additive Manufacturing and Practical Justification. Appl. Mater. Today 2024, 40, 102371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotti, A.; Paduano, T.; Napolitano, F.; Zuppolini, S.; Zarrelli, M.; Borriello, A. Fused Deposition Modeling of Polymer Composites: Development, Properties and Applications. Polymers 2025, 17, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesicek, J.; Alexa, P.; Posmykova, E.; Ma, Q.-P.; Musil, A.; Hajnys, J.; Olsovska, E.; Petru, J. Effect of Part Orientation and Thickness on Radiation Shielding in FDM 3D Printing of PET-G Composite with Tungsten. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 38, 2886–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.N.; Jiri, P.; Zbynek, S.; David, D. Effects of extrusion parameters on filament quality and mechanical properties of 3D printed PC/ABS components. MMS 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, S.; Durandet, Y.; Gao, W.; Huang, X.; Ruan, D. Strain Rate Dependence of 3D Printed Continuous Fiber Reinforced Composites. Compos. Part B-Eng. 2024, 277, 111415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnik, F.; Vasko, M.; Handrik, M.; Dorciak, F.; Majko, J. Comparing Mechanical Properties of Composites Structures on ONYX Base with Different Density and Shape of Fill. In Proceedings of the 13th International Scientific Conference on Sustainable, Modern and Safe Transport (Transcom 2019), Novy Smokovec, Slovakia, 29–31 May 2019; Bujnak, J., Guagliano, M., Eds.; ELSEVIER: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 40, pp. 616–622. [Google Scholar]

- Ghabezi, P.; Flanagan, T.; Walls, M.; Harrison, N.M. Degradation Characteristics of 3D Printed Continuous Fibre-Reinforced PA6/Chopped Fibre Composites in Simulated Saltwater. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 10, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellaisamy, S.; Munusamy, R. Experimental Study of 3D Printed Carbon Fibre Sandwich Structures for Lightweight Applications. Def. Technol. 2024, 36, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiema, D.; Balland, P.; Sergent, A. Experimental and Numerical Investigations of 3D-Printed ONYX Parts Reinforced with Continuous Glass Fibers. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2024, 24, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michal, P.; Vasko, M.; Sapieta, M.; Majko, J.; Fiacan, J. The Impact of Internal Structure Changes on the Damping Properties of 3D-Printed Composite Material. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, Ê.H.; Netto, J.V.B.; Ribeiro, M.L. Raw Dataset of Tensile Tests in a 3D-Printed Nylon Reinforced with Oriented Short Carbon Fibers. Data Br. 2024, 57, 111149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedrtnam, A.; Ghabezi, P.; Gunwant, D.; Jiang, Y.; Sam-Daliri, O.; Harrison, N.; Goggins, J.; Finnegan, W. Mechanical Performance of 3D-Printed Continuous Fibre ONYX Composites for Drone Applications: An Experimental and Numerical Analysis. Compos. Part C Open Access 2023, 12, 100418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.A.; Kumar, K.S.; Reddy, A.C. Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed ONYX-Fibreglass Composites: Role of Roof Layers on Tensile Strength and Hardness—Using Anova Technique. Next Mater. 2025, 8, 100650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnik, F.; Vasko, M.; Saga, M.; Handrik, M.; Sapietova, A. Mechanical Properties of Structures Produced by 3D Printing from Composite Materials. In Proceedings of the XXIII Polish-Slovak Scientific Conference on Machine Modelling and Simulations (MMS 2018), Rydzyna, Poland, 4–7 September 2018; Malujda, I., Dudziak, M., Krawiec, P., Talaska, K., Wilczynski, D., Berdychowski, M., Gorecki, J., Wargula, L., Wojtkowiak, D., Eds.; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2019; Volume 254. [Google Scholar]

- Lakomy, M.; Kluczynski, J.; Sarzynski, B.; Jasik, K.; Szachogluchowicz, I.; Luszczek, J. Bending Strength of Continuous Fiber-Reinforced (CFR) Polyamide-Based Composite Additively Manufactured through Material Extrusion. Materials 2024, 17, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.-W.; Kim, T.-H.; Yun, J.-H.; Kim, N.-J.; Ahn, K.-H.; Kang, M.-S. Strength of ONYX-Based Composite 3D Printing Materials According to Fiber Reinforcement. Front. Mater. 2023, 10, 1183816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, R.; Bucaciuc, S.-G.; Mandoc, A.C. Reducing Surface Roughness of 3D Printed Short-Carbon Fiber Reinforced Composites. Materials 2022, 15, 7398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.-H.; Yoon, G.-W.; Jeon, Y.-J.; Kang, M.-S. Evaluation of the Properties of 3D-Printed ONYX-Fiberglass Composites. Materials 2024, 17, 4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasik, K.; Sniezek, L.; Kluczynski, J. Additive Manufacturing of Metals Using the MEX Method: Process Characteristics and Performance Properties—A Review. Materials 2025, 18, 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzikalla, D.; Měsíček, J.; Halama, R.; Hajnyš, J.; Pagáč, M.; Čegan, T.; Petrů, J. On Flexural Properties of Additive Manufactured Composites: Experimental, and Numerical Study. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2022, 218, 109182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalova, M.; Rusnakova, S.; Krzikalla, D.; Mesicek, J.; Tomasek, R.; Podeprelova, A.; Rosicky, J.; Pagac, M. 3D Printed Hollow Off-Axis Profiles Based on Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymers: Mechanical Testing and Finite Element Method Analysis. Polymers 2021, 13, 2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbon Fiber. Available online: https://support.markforged.com/portal/s/article/Carbon-Fiber (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- ONYX. Available online: https://support.markforged.com/portal/s/article/Onyx (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- ISO 527-1:2019; Plastics—Determination of Tensile Properties Part 1: General Principles. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Bochnia, J.; Blasiak, M.; Kozior, T. Tensile Strength Analysis of Thin-Walled Polymer Glass Fiber Reinforced Samples Manufactured by 3d Printing Technology. Polymers 2020, 12, 2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bochnia, J.; Blasiak, M.; Kozior, T. A Comparative Study of the Mechanical Properties of FDM 3D Prints Made of PLA and Carbon Fiber-Reinforced PLA for Thin-Walled Applications. Materials 2021, 14, 7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochnia, J.; Kozior, T.; Zyz, J. The Mechanical Properties of Direct Metal Laser Sintered Thin-Walled Maraging Steel (MS1) Elements. Materials 2023, 16, 4699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udroiu, R. Quality Analysis of Micro-Holes Made by Polymer Jetting Additive Manufacturing. Polymers 2024, 16, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Property | ONYX | CF |

|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength (MPa) | 40 | 800 |

| Tensile Modulus (GPa) | 2.4 | 60 |

| Tensile Strain at Break (%) | 25 | 1.5 |

| Support material | ONYX (used only for Y-oriented samples) |

| Reinforcement material (OCF) | Continuous Carbon Fiber |

| Nozzle temperature (ONYX) | 274 °C |

| Nozzle temperature (CF) | 252 °C |

| Layer height (ONYX samples) | 0.10 mm |

| Layer height (OCF sample) | 0.125 mm |

| Infill type | Solid fill (100%) |

| Wall layers | 2 |

| Roof/floor layers | 2 |

| Continuous fiber layers (OCF) | 4 |

| Fiber layout (OCF) | Isotropic (0°/45°/90°/135°), 2 concentric rings |

| Fiber placement mode | Entire Group |

| Slicing mode | Cloud slicing ON |

| No. | ā (mm) | (mm) | No. | ā (mm) | (mm) | No. | ā (mm) | (mm) | No. | ā (mm) | (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-1-X-1 | 1.09 | 5.27 | O-1_4-X-1 | 1.52 | 5.13 | O-1_8-X-1 | 1.93 | 5.24 | O-4-X-1 | 4.15 | 5.09 |

| O-1-X-2 | 1.07 | 5.13 | O-1_4-X-2 | 1.51 | 5.11 | O-1_8-X-2 | 1.95 | 5.16 | O-4-X-2 | 4.16 | 5.24 |

| O-1-X-3 | 1.06 | 5.13 | O-1_4-X-3 | 1.47 | 5.20 | O-1_8-X-3 | 1.97 | 5.17 | O-4-X-3 | 4.19 | 5.10 |

| O-1-X-4 | 1.12 | 5.19 | O-1_4-X-4 | 1.52 | 5.21 | O-1_8-X-4 | 1.93 | 5.10 | O-4-X-4 | 4.18 | 5.12 |

| O-1-X-5 | 1.01 | 5.16 | O-1_4-X-5 | 1.53 | 5.13 | O-1_8-X-5 | 1.91 | 5.13 | O-4-X-5 | 4.19 | 5.17 |

| 1.07 | 5.18 | 1.51 | 5.16 | 1.94 | 5.16 | 4.17 | 5.14 | ||||

| SD | 0.04 | 0.06 | SD | 0.02 | 0.05 | SD | 0.02 | 0.05 | SD | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| O-1-Y-1 | 1.27 | 5.21 | O-1_4-Y-1 | 1.73 | 5.21 | O-1_8-Y-1 | 1.88 | 5.13 | O-4-Y-1 | 4.04 | 5.19 |

| O-1-Y-2 | 1.28 | 5.20 | O-1_4-Y-2 | 1.66 | 5.14 | O-1_8-Y-2 | 1.85 | 5.13 | O-4-Y-2 | 3.98 | 5.13 |

| O-1-Y-3 | 1.19 | 5.19 | O-1_4-Y-3 | 1.71 | 5.17 | O-1_8-Y-3 | 1.87 | 5.15 | O-4-Y-3 | 4.05 | 5.23 |

| O-1-Y-4 | 1.29 | 5.17 | O-1_4-Y-4 | 1.63 | 5.14 | O-1_8-Y-4 | 1.89 | 5.12 | O-4-Y-4 | 4.07 | 5.27 |

| O-1-Y-5 | 1.14 | 5.14 | O-1_4-Y-5 | 1.60 | 5.12 | O-1_8-Y-5 | 1.86 | 5.12 | O-4-Y-5 | 4.03 | 5.24 |

| 1.23 | 5.18 | 1.67 | 5.16 | 1.87 | 5.13 | 4.03 | 5.21 | ||||

| SD | 0.07 | 0.03 | SD | 0.05 | 0.04 | SD | 0.02 | 0.01 | SD | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| O-1-Z-1 | 1.84 | 5.41 | O-1_4-Z-1 | 1.83 | 5.35 | O-1_8-Z-1 | 2.05 | 5.29 | O-4-Z-1 | 4.08 | 5.12 |

| O-1-Z-2 | 1.54 | 5.24 | O-1_4-Z-2 | 1.83 | 5.33 | O-1_8-Z-2 | 2.07 | 5.31 | O-4-Z-2 | 4.07 | 5.10 |

| O-1-Z-3 | 1.83 | 4.91 | O-1_4-Z-3 | 1.85 | 5.41 | O-1_8-Z-3 | 2.07 | 5.32 | O-4-Z-3 | 4.10 | 5.11 |

| O-1-Z-4 | 1.57 | 5.33 | O-1_4-Z-4 | 1.83 | 5.35 | O-1_8-Z-4 | 2.08 | 5.35 | O-4-Z-4 | 4.05 | 5.46 |

| O-1-Z-5 | 1.56 | 5.29 | O-1_4-Z-5 | 1.86 | 5.35 | O-1_8-Z-5 | 2.07 | 5.29 | O-4-Z-5 | 4.09 | 5.11 |

| 1.67 | 5.24 | 1.84 | 5.36 | 2.07 | 5.31 | 4.08 | 5.18 | ||||

| SD | 0.15 | 0.19 | SD | 0.01 | 0.03 | SD | 0.01 | 0.02 | SD | 0.02 | 0.16 |

| No. | ā (mm) | (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| OCF-4-X-1 | 4.13 | 5.08 |

| OCF-4-X-2 | 4.17 | 5.07 |

| OCF-4-X-3 | 4.15 | 5.13 |

| OCF-4-X-4 | 4.15 | 5.11 |

| OCF-4-X-5 | 4.14 | 5.09 |

| 4.15 | 5.10 | |

| SD | 0.015 | 0.024 |

| No. | Rm (MPa) | εm (%) | No. | Rm (MPa) | εm (%) | No. | Rm (MPa) | εm (%) | No. | Rm (MPa) | εm (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-1-X-1 | 28.71 | 38.2 | O-1_4-X-1 | 29.60 | 44.4 | O-1_8-X-1 | 30.40 | 54.6 | O-4-X-1 | 32.07 | 54.8 |

| O-1-X-2 | 26.63 | 37.0 | O-1_4-X-2 | 29.32 | 50.0 | O-1_8-X-2 | 31.60 | 53.2 | O-4-X-2 | 30.72 | 51.3 |

| O-1-X-3 | 26.98 | 36.4 | O-1_4-X-3 | 30.92 | 58.9 | O-1_8-X-3 | 30.48 | 46.4 | O-4-X-3 | 31.42 | 49.9 |

| O-1-X-4 | 26.27 | 42.5 | O-1_4-X-4 | 28.31 | 55.4 | O-1_8-X-4 | 31.82 | 49.9 | O-4-X-4 | 31.20 | 51.7 |

| O-1-X-5 | 29.98 | 40.1 | O-1_4-X-5 | 30.10 | 53.7 | O-1_8-X-5 | 33.06 | 51.7 | O-4-X-5 | 30.85 | 56.8 |

| 27.71 | 38.8 | 29.65 | 52.7 | 31.47 | 51.2 | 31.25 | 52.9 | ||||

| SD | 1.58 | 2.5 | SD | 0.97 | 5.5 | SD | 1.09 | 3.2 | SD | 0.53 | 2.8 |

| V | 5.7 | 6.4 | V | 3.3 | 10.4 | V | 3.5 | 6.3 | V | 1.7 | 5.3 |

| O-1-Y-1 | 47.75 | 24.3 | O-1_4-Y-1 | 48.49 | 25.0 | O-1_8-Y-1 | 56.15 | 24.7 | O-4-Y-1 | 39.82 | 28.9 |

| O-1-Y-2 | 48.58 | 23.7 | O-1_4-Y-2 | 49.88 | 29.0 | O-1_8-Y-2 | 51.43 | 24.3 | O-4-Y-2 | 40.19 | 28.2 |

| O-1-Y-3 | 50.02 | 23.1 | O-1_4-Y-3 | 48.72 | 28.1 | O-1_8-Y-3 | 56.58 | 21.3 | O-4-Y-3 | 38.67 | 30.2 |

| O-1-Y-4 | 48.99 | 24.5 | O-1_4-Y-4 | 49.40 | 30.8 | O-1_8-Y-4 | 55.78 | 21.0 | O-4-Y-4 | 36.16 | 27.9 |

| O-1-Y-5 | 49.78 | 24.9 | O-1_4-Y-5 | 49.39 | 28.7 | O-1_8-Y-5 | 54.00 | 20.6 | O-4-Y-5 | 36.10 | 28.7 |

| 49.02 | 24.1 | 49.18 | 28.3 | 54.79 | 22.4 | 38.19 | 28.8 | ||||

| SD | 0.92 | 0.7 | SD | 0.56 | 2.1 | SD | 2.12 | 2.0 | SD | 1.96 | 0.9 |

| V | 1.9 | 2.9 | V | 1.1 | 7.4 | V | 3.9 | 8.9 | V | 5.1 | 3.1 |

| O-1-Z-1 | 15.42 | 6.4 | O-1_4-Z-1 | 27.18 | 10.7 | O-1_8-Z-1 | 27.34 | 12.0 | O-4-Z-1 | 23.02 | 10.4 |

| O-1-Z-2 | 24.61 | 10.5 | O-1_4-Z-2 | 27.11 | 10.5 | O-1_8-Z-2 | 29.67 | 17.5 | O-4-Z-2 | 26.82 | 14.1 |

| O-1-Z-3 | 25.88 | 27.4 | O-1_4-Z-3 | 29.07 | 13.8 | O-1_8-Z-3 | 25.54 | 10.5 | O-4-Z-3 | 26.21 | 12.8 |

| O-1-Z-4 | 20.47 | 9.8 | O-1_4-Z-4 | 32.00 | 17.9 | O-1_8-Z-4 | 30.04 | 20.3 | O-4-Z-4 | 24.72 | 13.7 |

| O-1-Z-5 | 20.04 | 8.6 | O-1_4-Z-5 | 28.35 | 12.8 | O-1_8-Z-5 | 29.83 | 16.1 | O-4-Z-5 | 27.82 | 15.7 |

| 21.28 | 12.6 | 28.74 | 13.1 | 28.48 | 15.3 | 25.72 | 13.3 | ||||

| SD | 4.15 | 8.4 | SD | 2.00 | 3.0 | SD | 1.98 | 4.0 | SD | 1.88 | 2.0 |

| V | 19.5 | 6.7 | V | 7 | 22.9 | V | 7 | 26.1 | V | 7.3 | 15 |

| No. | Rm (MPa) | εm (%) |

|---|---|---|

| OCF-4-X-1 | 92.05 | 13.8 |

| OCF-4-X-2 | 86.74 | 18.0 |

| OCF-4-X-3 | 93.15 | 14.4 |

| OCF-4-X-4 | 92.64 | 13.5 |

| OCF-4-X-5 | 90.65 | 13.6 |

| 91.05 | 14.7 | |

| SD | 2.58 | 1.9 |

| V | 2.8 | 12.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kozior, T.; Bochnia, J.; Hajnys, J.; Mesicek, J. Continuous Filament Fabrication Technology and Its Mechanical Properties for Thin-Walled Component. Materials 2026, 19, 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010144

Kozior T, Bochnia J, Hajnys J, Mesicek J. Continuous Filament Fabrication Technology and Its Mechanical Properties for Thin-Walled Component. Materials. 2026; 19(1):144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010144

Chicago/Turabian StyleKozior, Tomasz, Jerzy Bochnia, Jiri Hajnys, and Jakub Mesicek. 2026. "Continuous Filament Fabrication Technology and Its Mechanical Properties for Thin-Walled Component" Materials 19, no. 1: 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010144

APA StyleKozior, T., Bochnia, J., Hajnys, J., & Mesicek, J. (2026). Continuous Filament Fabrication Technology and Its Mechanical Properties for Thin-Walled Component. Materials, 19(1), 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010144