Laser Remelting of Biocompatible Ti-Based Glass-Forming Alloys: Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, and Cytotoxicity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. SLM Printing

2.2. Microstructural Characterization

2.3. Mechanical Testing (Nanoindentation)

2.4. Cytotoxicity Testing

2.4.1. Indirect Assay

2.4.2. Direct Contact Assay

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructure

- (a)

- Ti42Zr35Si5Co12.5Sn2.5Ta3

- (b)

- Ti42Zr40Ta3Si15

- (c)

- Ti60Nb15Zr10Si15

- (d)

- Ti39Zr32Si29

- (e)

- Ti65.5Fe22.5Si12

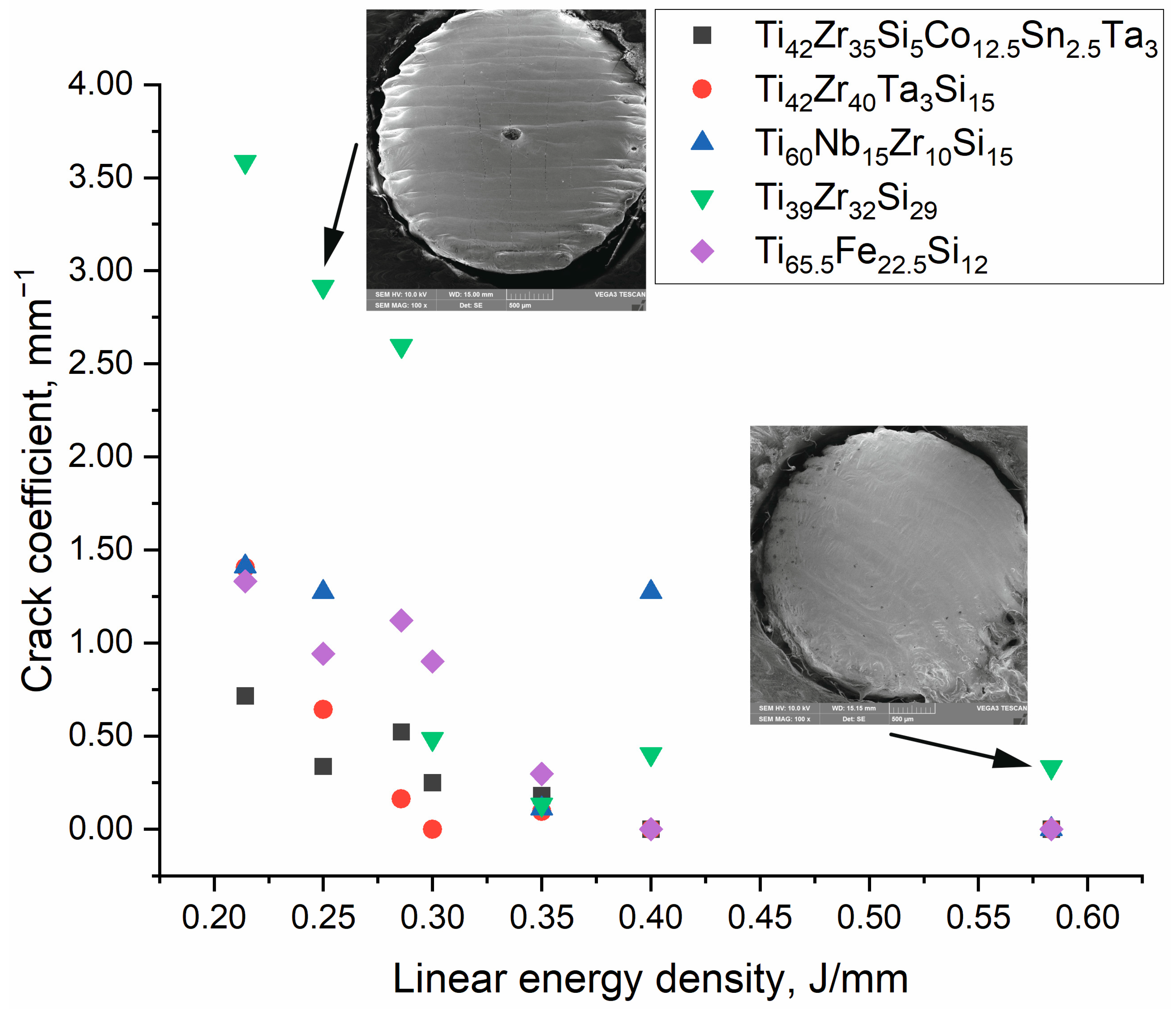

3.2. Crack Density

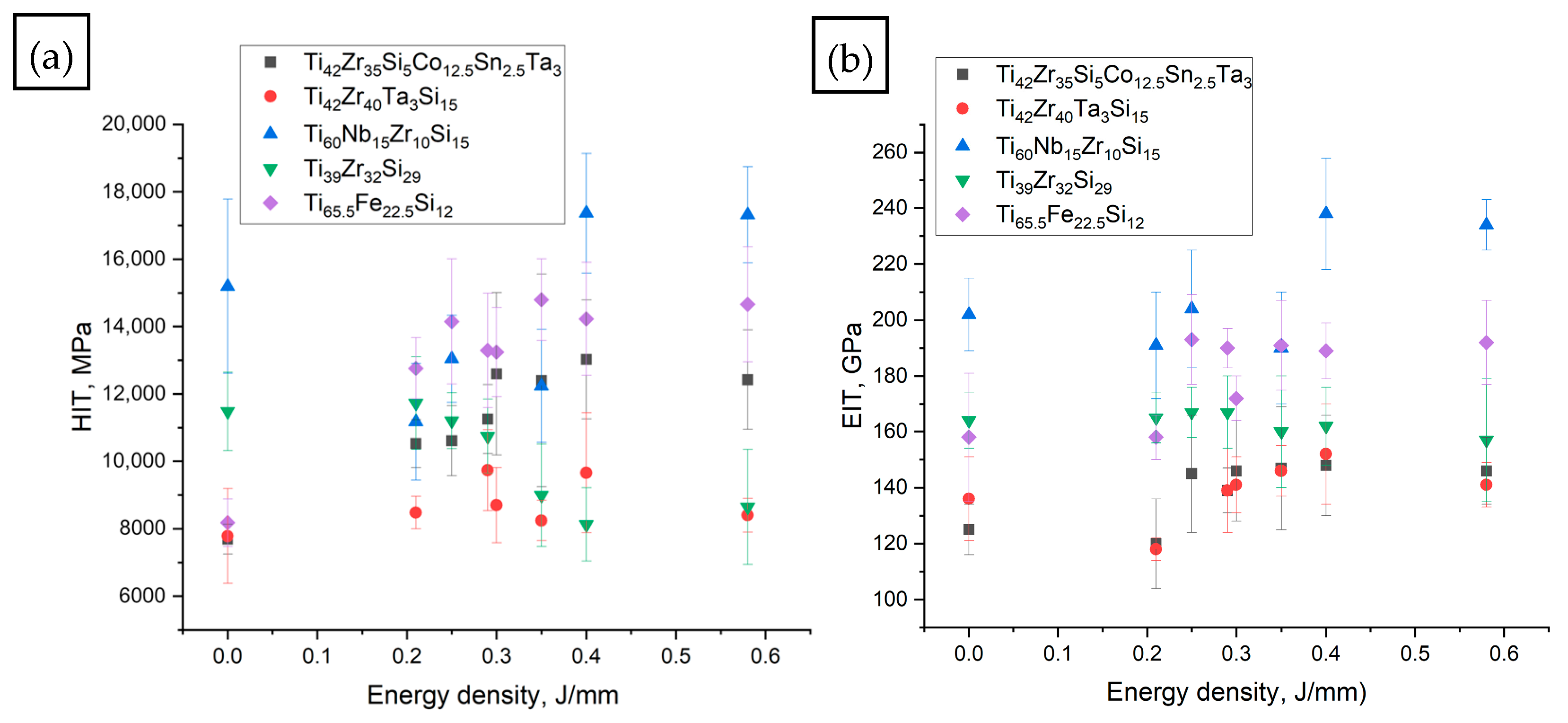

3.3. Hardness and E-Moduli

3.4. Cytotoxicity Assessment

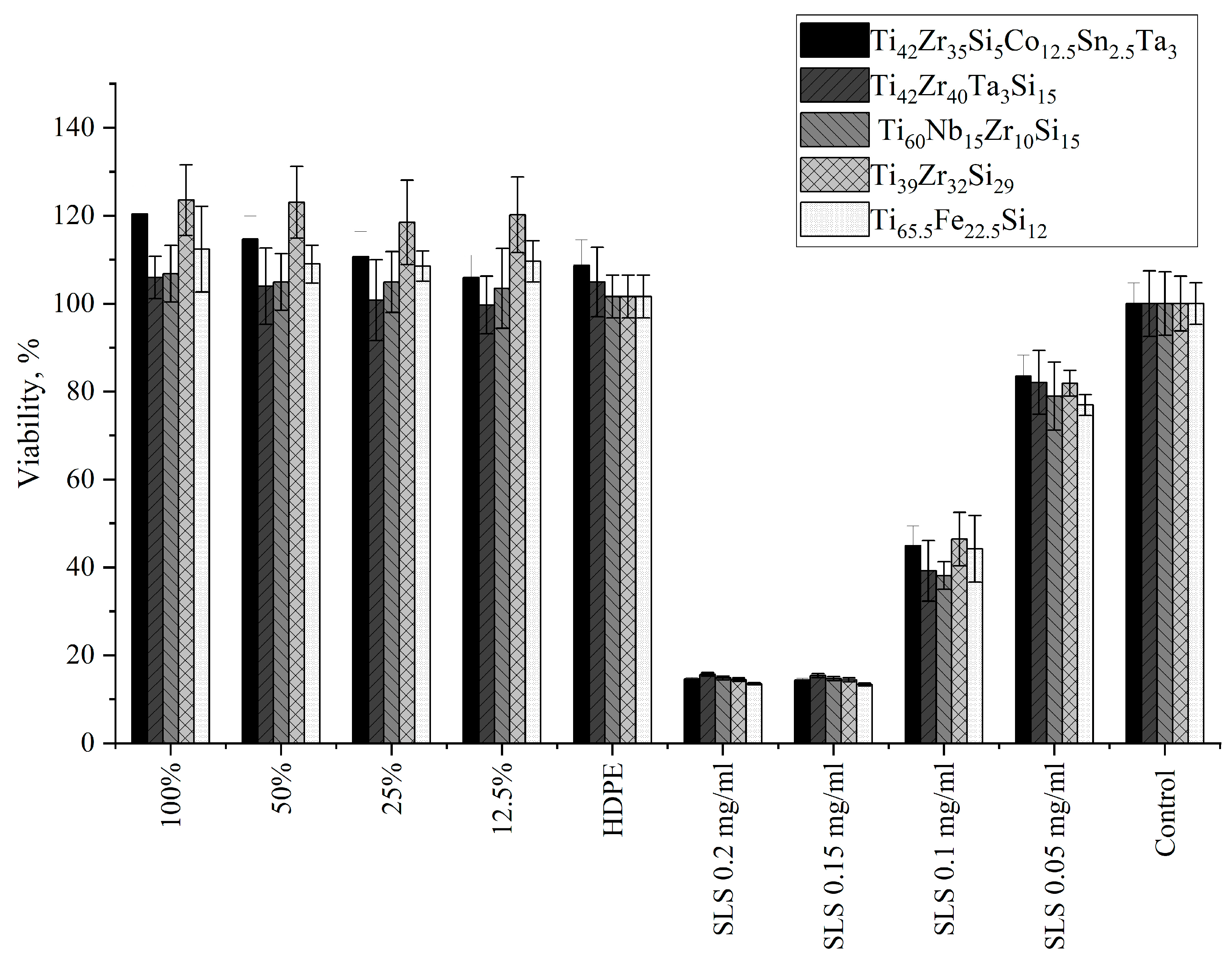

3.4.1. Indirect Contact Method (Extract Test)

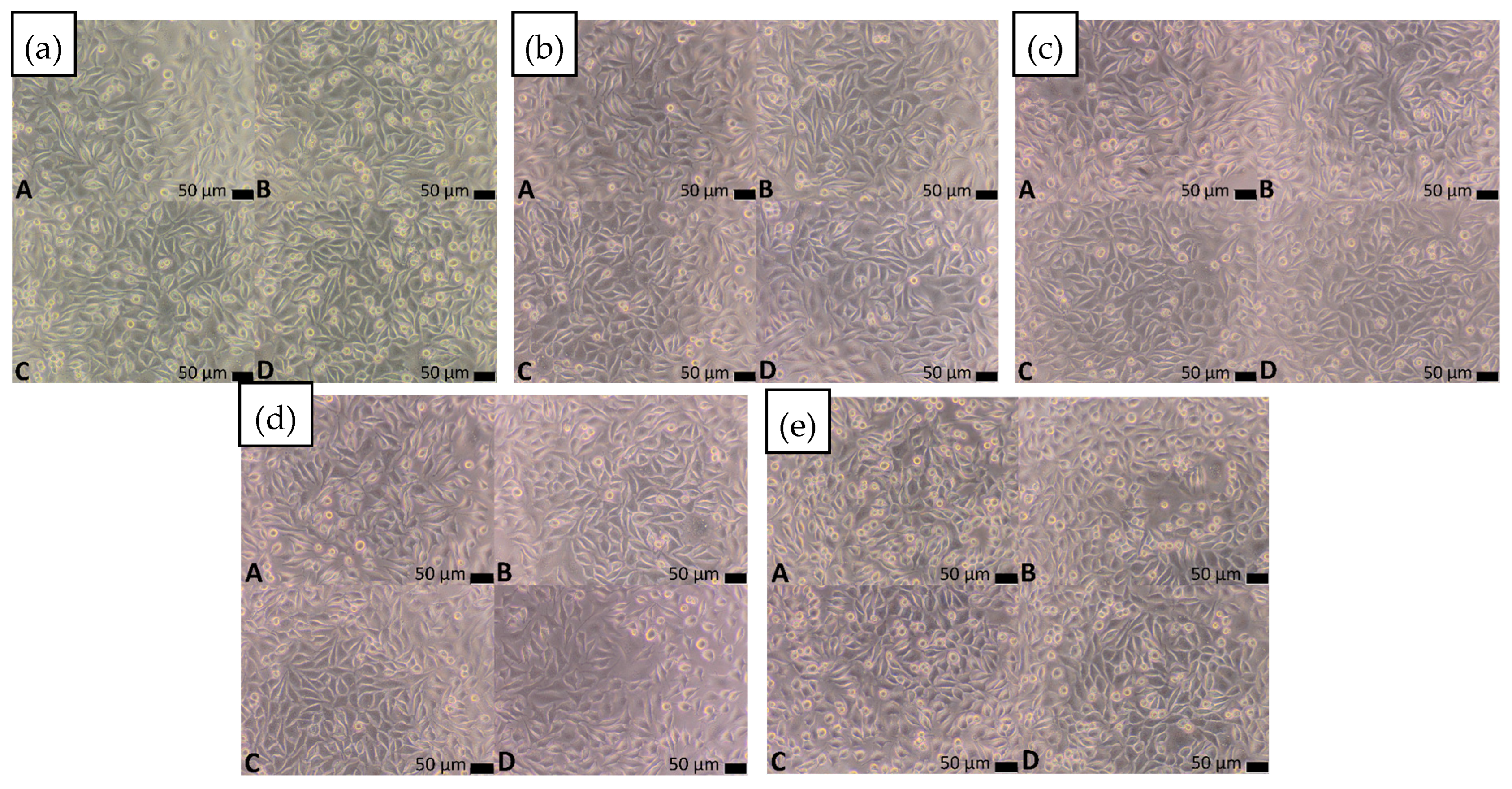

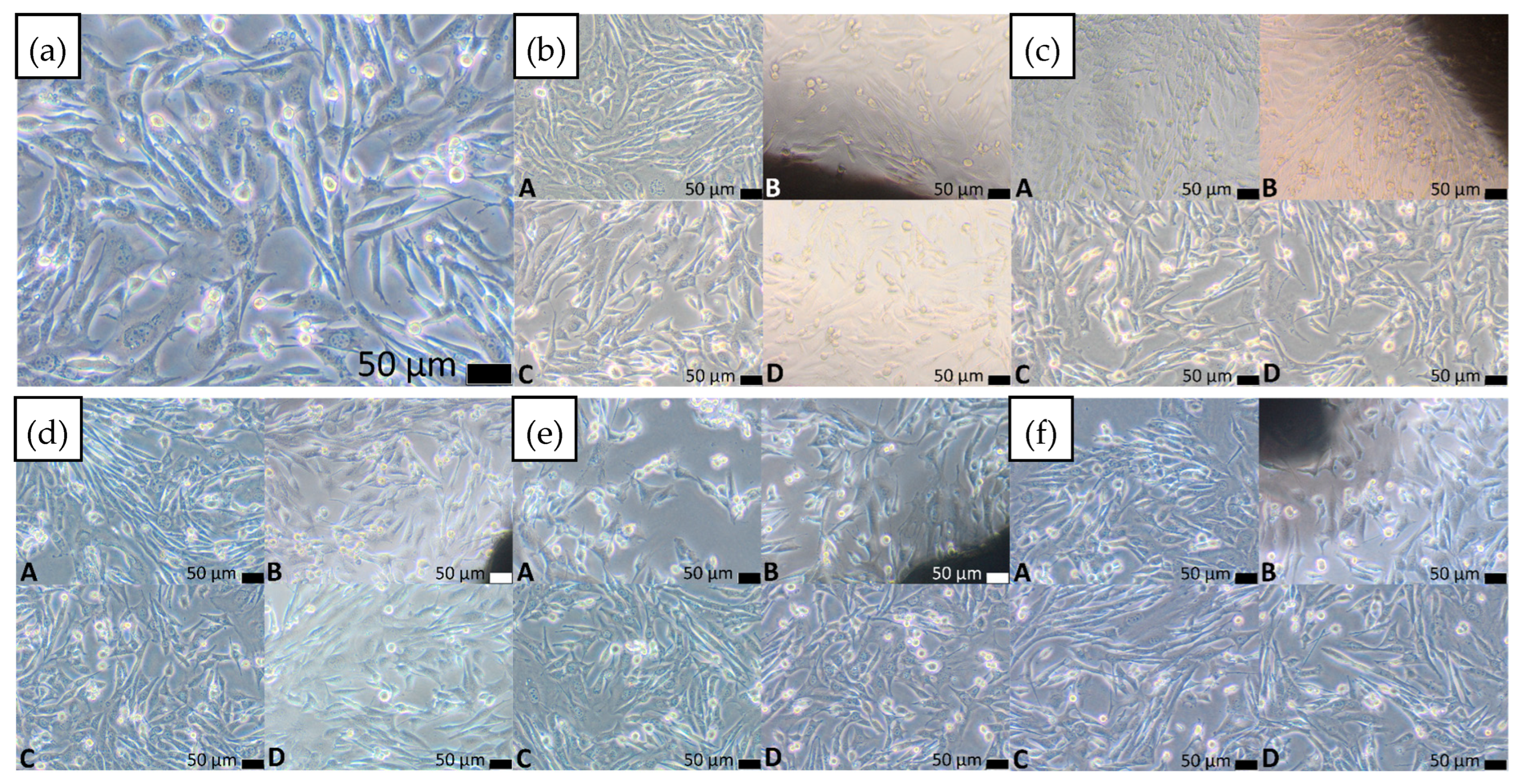

3.4.2. Direct Contact Method

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Simcoe, C.R. The History of Metals in America; Richards, F., Simcoe, C.R., Eds.; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781627081467. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, F.; Clausing, R.J.; Stiller, A.; Fonseca Ulloa, C.A.; Foelsch, C.; Rickert, M.; Jahnke, A. Determination of E-modulus of cancellous bone derived from human humeri and validation of plotted single trabeculae: Development of a standardized humerus bone model. J. Orthop. 2022, 33, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parshina, I.F.; Dol’, A.V.; Bessonov, L.V.; Falkovich, A.S.; Ivanov, D.V. On the Question of the Effect of the Loading Method on the Cancellous Bone Effective Elasticity Modulus. Mech. Solids 2024, 59, 3870–3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Ovaert, T.C.; Niebur, G.L. Viscoelastic properties of human cortical bone tissue depend on gender and elastic modulus. J. Orthop. Res. 2012, 30, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zioupos, P.; Currey, J.D. Changes in the stiffness, strength, and toughness of human cortical bone with age. Bone 1998, 22, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehmer, B.; Bayram, F.; Ávila Calderón, L.A.; Mohr, G.; Skrotzki, B. BAM Reference Data: Temperature-Dependent Young’s and Shear Modulus Data for Additively and Conventionally Manufactured Variants of Ti-6Al-4V. 2025. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/14617243 (accessed on 20 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Niinomi, M.; Nakai, M. Titanium-Based Biomaterials for Preventing Stress Shielding between Implant Devices and Bone. Int. J. Biomater. 2011, 2011, 836587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, C.; Tan, Y.; Hui, D.; Zhai, Y. Design and Mechanical Performance Analysis of Ti6Al4V Biomimetic Bone with One-Dimensional Continuous Gradient Porous Structures. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2024, 34, 15799–15822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjandra, J.; Alabort, E.; Barba, D.; Pedrazzini, S. Corrosion, fatigue and wear of additively manufactured Ti alloys for orthopaedic implants. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 39, 2951–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, D.M.; Santos, S.G.; Lamghari, M.; Barbosa, M.A. The two faces of metal ions: From implants rejection to tissue repair/regeneration. Biomaterials 2016, 84, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, B.C.; Tokuhara, C.K.; Rocha, L.A.; Oliveira, R.C.; Lisboa-Filho, P.N.; Costa Pessoa, J. Vanadium ionic species from degradation of Ti-6Al-4V metallic implants: In vitro cytotoxicity and speciation evaluation. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2019, 96, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.; Pan, X.; Chen, Y.; Lian, Q.; Gao, J.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Shi, Z.; Cheng, H. Prosthetic Metals: Release, Metabolism and Toxicity. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 5245–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magone, K.; Luckenbill, D.; Goswami, T. Metal ions as inflammatory initiators of osteolysis. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2015, 135, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-Elaziem, W.; Darwish, M.A.; Hamada, A.; Daoush, W.M. Titanium-Based alloys and composites for orthopedic implants Applications: A comprehensive review. Mater. Des. 2024, 241, 112850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüce, E.; Spieckermann, F.; Asci, A.; Wurster, S.; Ramasamy, P.; Xi, L.; Sarac, B.; Eckert, J. Toxic element-free Ti-based metallic glass ribbons with precious metal additions. Mater. Today Adv. 2023, 19, 100392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüce, E.; Zarazúa-Villalobos, L.; Ter-Ovanessian, B.; Sharifikolouei, E.; Najmi, Z.; Spieckermann, F.; Eckert, J.; Sarac, B. New-generation biocompatible Ti-based metallic glass ribbons for flexible implants. Mater. Des. 2022, 223, 111139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calin, M.; Gebert, A.; Ghinea, A.C.; Gostin, P.F.; Abdi, S.; Mickel, C.; Eckert, J. Designing biocompatible Ti-based metallic glasses for implant applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2013, 33, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.Q.; Zhang, H.F.; Zhu, Z.W.; Fu, H.M.; Wang, A.M.; Li, H.; Hu, Z.Q. TiZr-base Bulk Metallic Glass with over 50 mm in Diameter. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2010, 26, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.L.; Wang, X.M.; Qin, F.X.; Inoue, A. A new Ti-based bulk glassy alloy with potential for biomedical application. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 459, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.L.; Wang, X.M.; Inoue, A. Glass-forming ability and mechanical properties of Ti-based bulk glassy alloys with large diameters of up to 1cm. Intermetallics 2008, 16, 1031–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Zhu, B.; Yang, X.; Xie, G. Toxic elements-free low-cost Ti-Fe-Si metallic glass biomaterial developed by mechanical alloying. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 886, 161290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Liu, Y.; Hua, N.; Pang, S.; Li, Y.; Liaw, P.K.; Zhang, T. Formation and properties of biocompatible Ti-based bulk metallic glasses in the Ti–Cu–Zr–Fe–Sn–Si–Ag system. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2021, 571, 121060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Bataev, I.; Georgarakis, K.; Jorge, A.M.; Nogueira, R.P.; Pons, M.; Yavari, A.R. Ni- and Cu-free Ti-based metallic glasses with potential biomedical application. Intermetallics 2015, 63, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.L.; Huang, C.H.; Chen, Y.H.; Tsai, W.Y.; Wei, T.Y.; Huang, J.C. In vitro biocompatibility response of Ti–Zr–Si thin film metallic glasses. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 322, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Li, K.; Zhu, B.; Xiang, T.; Xie, G. Development of non-toxic low-cost bioactive porous Ti–Fe–Si bulk metallic glass with bone-like mechanical properties for orthopedic implants. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 17, 1319–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-C.; Attar, H.; Calin, M.; Eckert, J. Review on manufacture by selective laser melting and properties of titanium based materials for biomedical applications. Mater. Technol. 2016, 31, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aufa, A.N.; Hassan, M.Z.; Ismail, Z. Recent advances in Ti-6Al-4V additively manufactured by selective laser melting for biomedical implants: Prospect development. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 896, 163072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, S.; Nour, S.; Attari, S.M.; Mohajeri, M.; Kianersi, S.; Taromian, F.; Khalkhali, M.; Aninwene, G.E.; Tayebi, L. A review on in vitro/in vivo response of additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V alloy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 9479–9534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, P.; Kühn, U.; Pauly, S. Selective laser melting of a Ti-based bulk metallic glass. Mater. Lett. 2018, 212, 346–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-S.; Tsai, P.-H.; Li, T.-H.; Jang, J.S.-C.; Huang, J.C.-C.; Lin, C.-H.; Pan, C.-T.; Lin, H.-K. Development and Fabrication of Biocompatible Ti-Based Bulk Metallic Glass Matrix Composites for Additive Manufacturing. Materials 2023, 16, 5935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoara, M.; Raduta, A.; Locovei, C.; Buzdugan, D.; Stoica, M. About thermostability of biocompatible Ti–Zr–Ta–Si amorphous alloys. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017, 127, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.C.; Tsai, P.H.; Ke, J.H.; Li, J.B.; Jang, J.; Huang, C.H.; Haung, J.C. Designing a toxic-element-free Ti-based amorphous alloy with remarkable supercooled liquid region for biomedical application. Intermetallics 2014, 55, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, S.; Khoshkhoo, M.S.; Shuleshova, O.; Bönisch, M.; Calin, M.; Schultz, L.; Eckert, J.; Baró, M.D.; Sort, J.; Gebert, A. Effect of Nb addition on microstructure evolution and nanomechanical properties of a glass-forming Ti–Zr–Si alloy. Intermetallics 2014, 46, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-EN ISO 10993-5:2009; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 5: Tests for In Vitro Cytotoxicity. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- PN-EN ISO 10993-12:2021; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 12: Sample Preparation and Reference Materials. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Chattopadhyay, C.; Murty, B.S. Kinetic modification of the ‘confusion principle’ for metallic glass formation. Scr. Mater. 2016, 116, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Du, P.; Li, K.; Chen, L.; Xie, G. A Review of the Development of Titanium-Based and Magnesium-Based Metallic Glasses in the Field of Biomedical Materials. Materials 2024, 17, 4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żrodowski, Ł.; Wysocki, B.; Wróblewski, R.; Krawczyńska, A.; Adamczyk-Cieślak, B.; Zdunek, J.; Błyskun, P.; Ferenc, J.; Leonowicz, M.; Święszkowski, W. New approach to amorphization of alloys with low glass forming ability via selective laser melting. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 771, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordbar-Khiabani, A.; Gasik, M. Electrochemical and biological characterization of Ti-Nb-Zr-Si alloy for orthopedic applications. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Liu, C.; Dai, S.; Deng, R. Microstructure, Properties and Crack Suppression Mechanism of High-speed Steel Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting at Different Process Parameters. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2023, 36, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madikizela, C.; Cornish, L.A.; Chown, L.H.; Möller, H. Microstructure and mechanical properties of selective laser melted Ti-3Al-8V-6Cr-4Zr-4Mo compared to Ti-6Al-4V. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 747, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachenko, S.; Cizek, J.; Mušálek, R.; Dvořák, K.; Spotz, Z.; Montufar, E.B.; Chráska, T.; Křupka, I.; Čelko, L. Metal matrix to ceramic matrix transition via feedstock processing of SPS titanium composites alloyed with high silicone content. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 764, 776–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, Y.; Bai, Q. Defect Formation Mechanisms in Selective Laser Melting: A Review. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2017, 30, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabor, C.; Cristea, D.; Velicu, I.-L.; Bedo, T.; Gatto, A.; Bassoli, E.; Varga, B.; Pop, M.A.; Geanta, V.; Stefanoiu, R.; et al. Ti-Zr-Si-Nb Nanocrystalline Alloys and Metallic Glasses: Assessment on the Structural Development, Thermal Stability, Corrosion and Mechanical Properties. Materials 2019, 12, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Q.; Wang, H.L.; Lin, J.G. Effects of Sn content on thermal stability and mechanical properties of the Ti60Zr10Ta15Si15 amorphous alloy for biomedical use. Mater. Des. 2014, 63, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnert, C.; Kuhnt, M.; Bruns, S.; Marshal, A.; Pradeep, K.G.; Marsilius, M.; Bruder, E.; Durst, K. Study on the embrittlement of flash annealed Fe85.2B9.5P4Cu0.8Si0.5 metallic glass ribbons. Mater. Des. 2018, 156, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, T.; Kobayashi, K.; Matsumoto, A.; Ozaki, K. Preparation and Characterization of Nano-Crystalline Ti-2 at%Fe-10 at%Si Alloy by Mechanical Alloying and Pulsed Current Sintering Process. Mater. Trans. 2003, 44, 2262–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lp | Laser Power, W | Scanning Speed, mm/s | ED, J/mm |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | as cast | - | 0 |

| 2 | 300 | 1400 | 0.21 |

| 3 | 350 | 1400 | 0.25 |

| 4 | 400 | 1400 | 0.29 |

| 5 | 300 | 1000 | 0.30 |

| 6 | 350 | 1000 | 0.35 |

| 7 | 400 | 1000 | 0.40 |

| 8 | 350 | 600 | 0.58 |

| Material | Cytotoxicity Score | Description of Changes in Cell Cultures | V% (Mean)—Extract (100%) | V% (Mean)—Control | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti42Zr35Si5Co12.5Sn2.5Ta3 | 0 | Single intracytoplasmic granules; no cell lysis observed; no inhibition of cell growth | 120.36 | 100.00 | 0.000161 |

| Ti42Zr40Ta3Si15 | 0 | Single intracytoplasmic granules; no cell lysis observed; no inhibition of cell growth | 105.95 | 100.00 | 0.579065 |

| Ti60Nb15Zr10Si15 | 0 | Single intracytoplasmic granules; no cell lysis observed; no inhibition of cell growth | 106.79 | 100.00 | 0.255255 |

| Ti39Zr32Si29 | 0 | Single intracytoplasmic granules; no cell lysis observed; no inhibition of cell growth | 123.53 | 100.00 | 0.000160 |

| Ti65.5Fe22.5Si12 | 0 | Single intracytoplasmic granules; no cell lysis observed; no inhibition of cell growth | 112.38 | 100.00 | 0.003157 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Małachowska, A.; Drej, W.; Rusak, A.; Kozieł, T.; Pikulski, D.; Stopyra, W. Laser Remelting of Biocompatible Ti-Based Glass-Forming Alloys: Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, and Cytotoxicity. Materials 2025, 18, 5687. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245687

Małachowska A, Drej W, Rusak A, Kozieł T, Pikulski D, Stopyra W. Laser Remelting of Biocompatible Ti-Based Glass-Forming Alloys: Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, and Cytotoxicity. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5687. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245687

Chicago/Turabian StyleMałachowska, Aleksandra, Wiktoria Drej, Agnieszka Rusak, Tomasz Kozieł, Denis Pikulski, and Wojciech Stopyra. 2025. "Laser Remelting of Biocompatible Ti-Based Glass-Forming Alloys: Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, and Cytotoxicity" Materials 18, no. 24: 5687. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245687

APA StyleMałachowska, A., Drej, W., Rusak, A., Kozieł, T., Pikulski, D., & Stopyra, W. (2025). Laser Remelting of Biocompatible Ti-Based Glass-Forming Alloys: Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, and Cytotoxicity. Materials, 18(24), 5687. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245687