Strategy Construction to Improve the Thermal Resistance of Polyimide-Matrix Composites Based on Fiber–Resin Compatibility

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

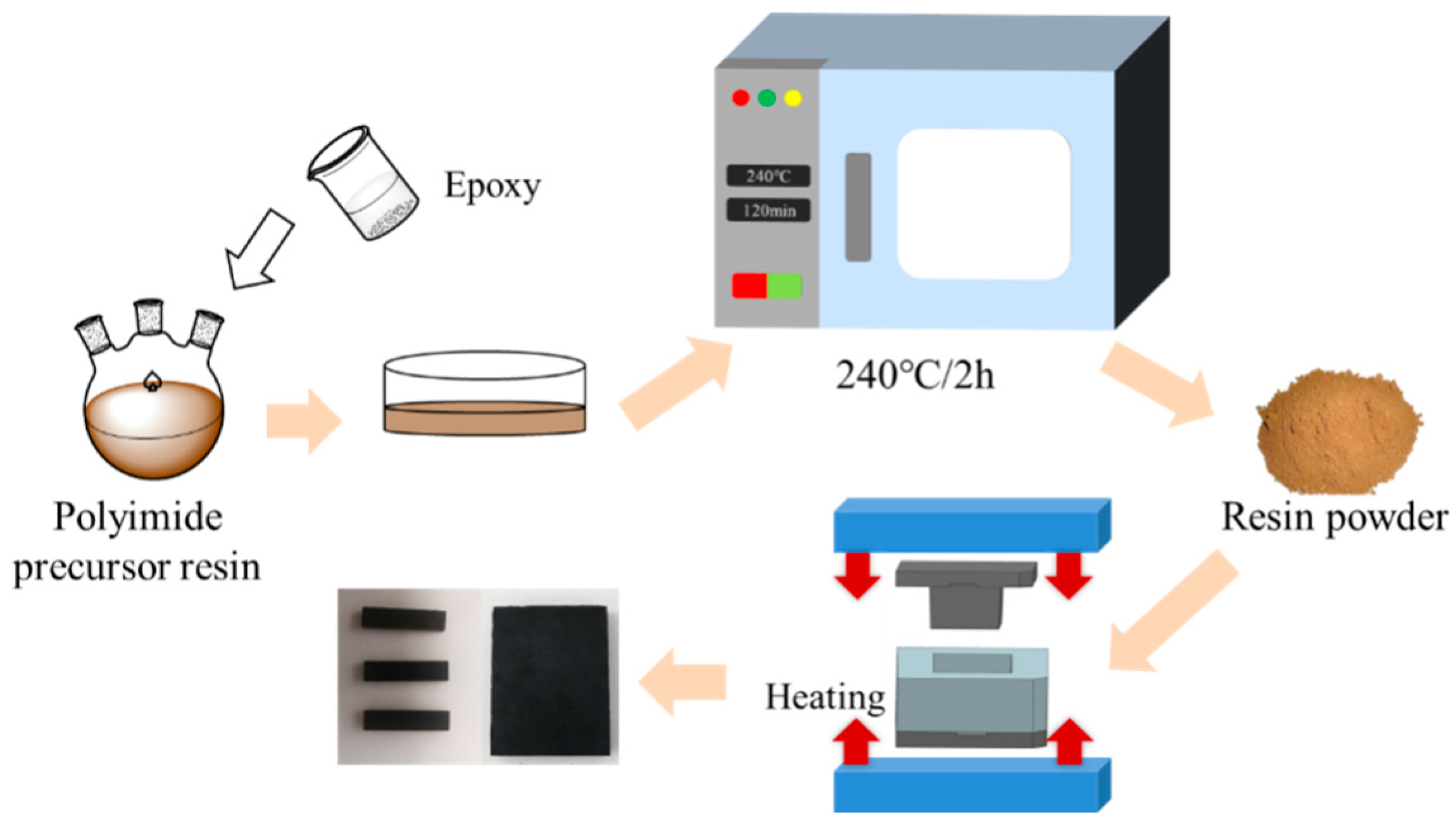

2.2. Blending of Epoxy–Polyimide Resin and Preparation of Molding Compounds

2.2.1. Blending of Epoxy and Polyimide Resin

2.2.2. Preparation of Blended Resin Molding Compounds

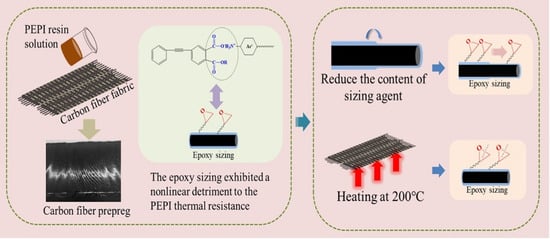

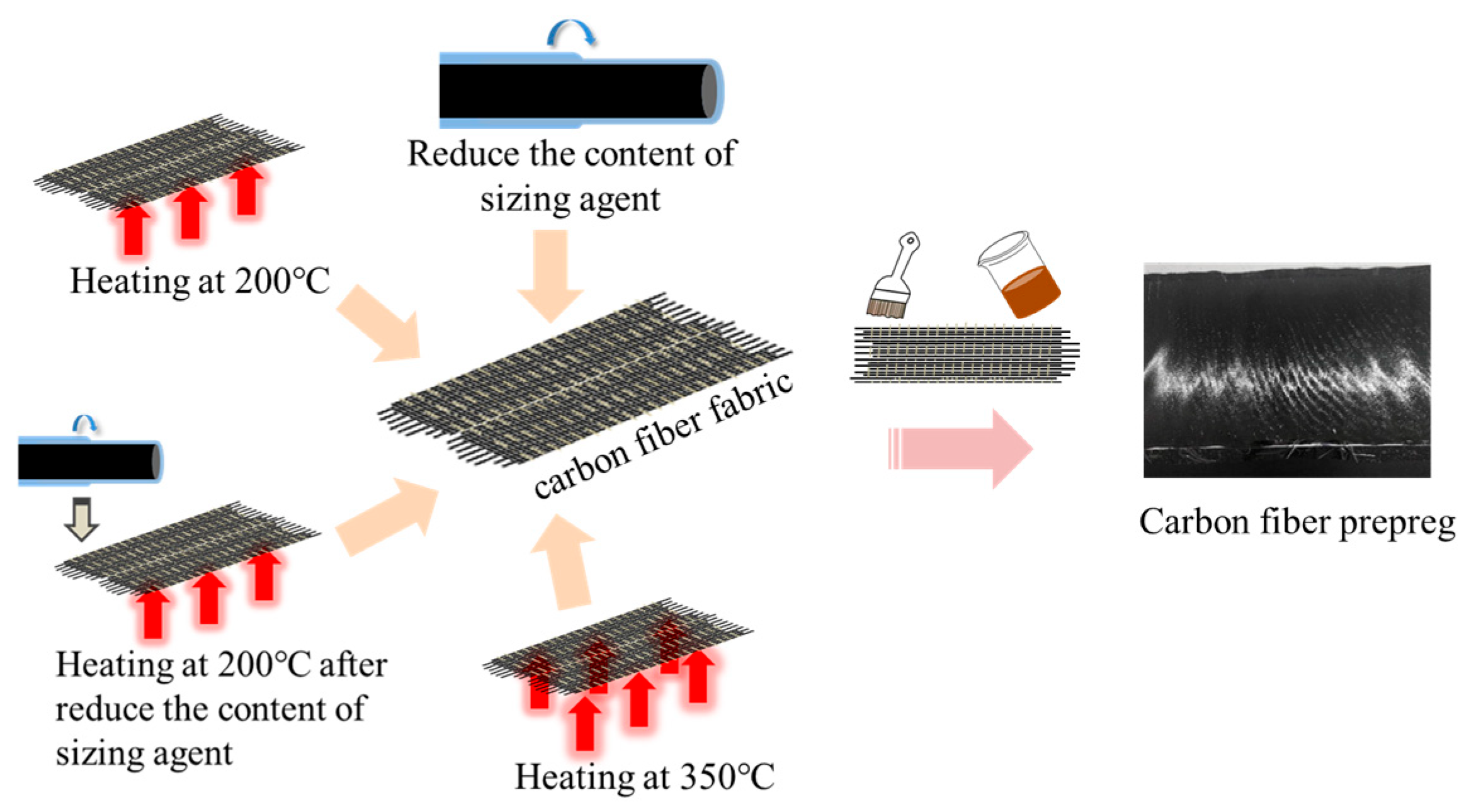

2.3. Treatment of Carbon Fiber with Epoxy Sizing Agent and Preparation of Composites

2.3.1. Treatment of Carbon Fiber with Epoxy Sizing Agent

2.3.2. Preparation of Polyimide Composite Laminates

2.4. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

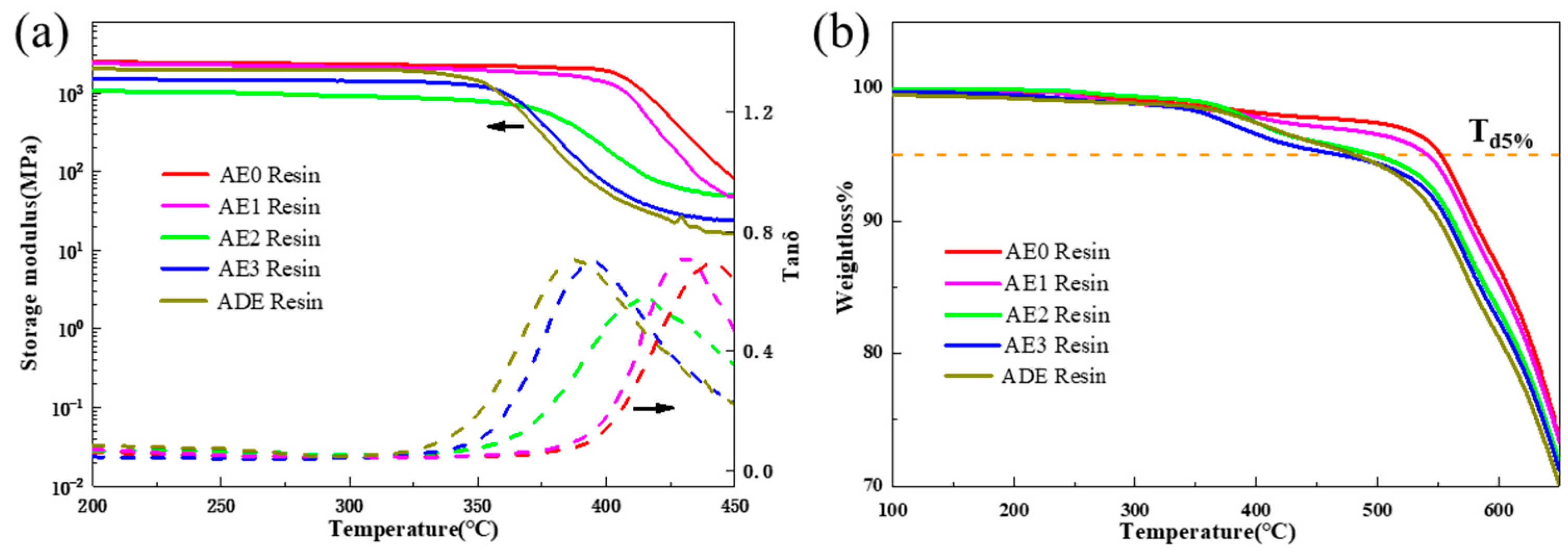

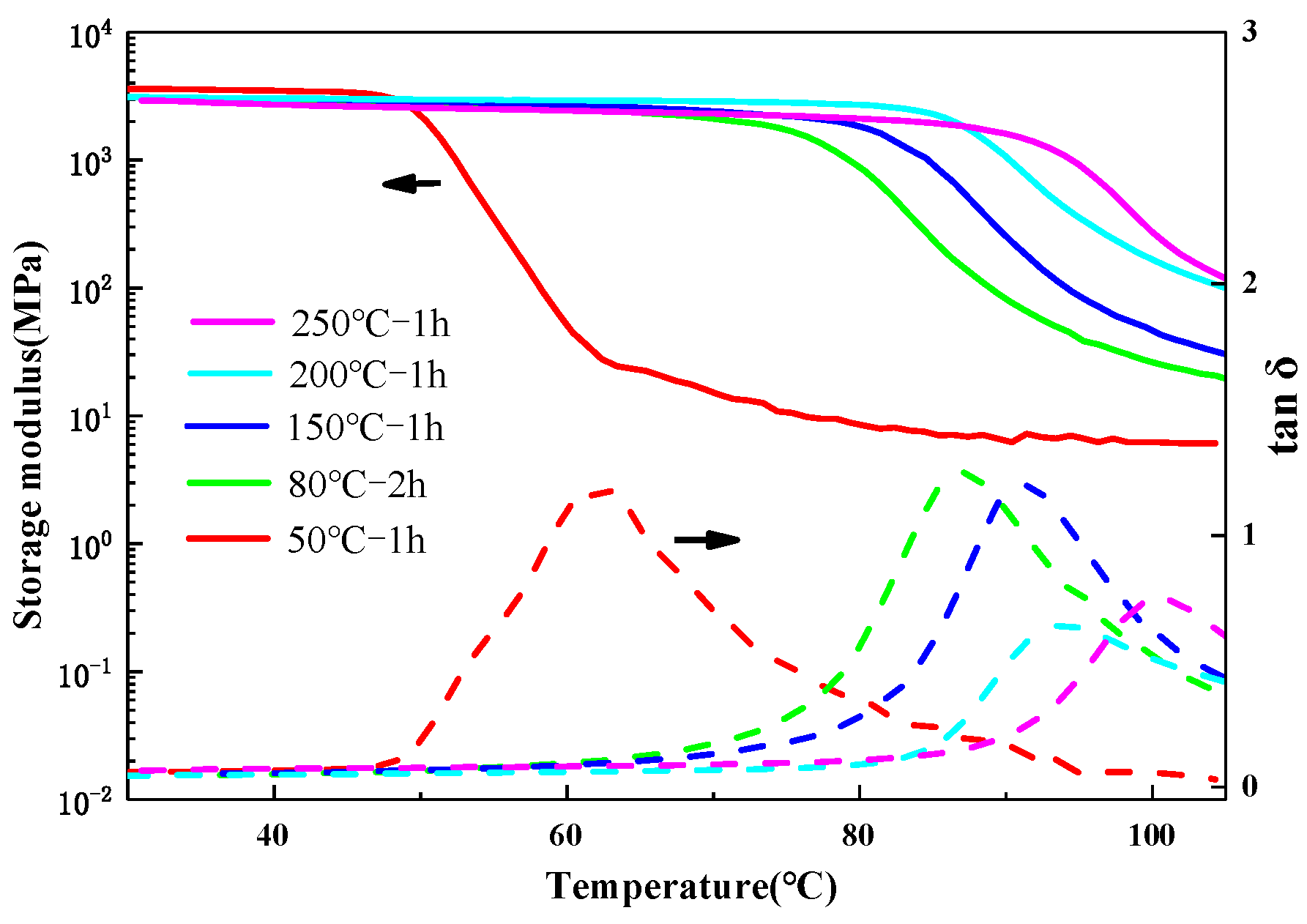

3.1. Thermal Resistance of the Polyimide–Epoxy Compound

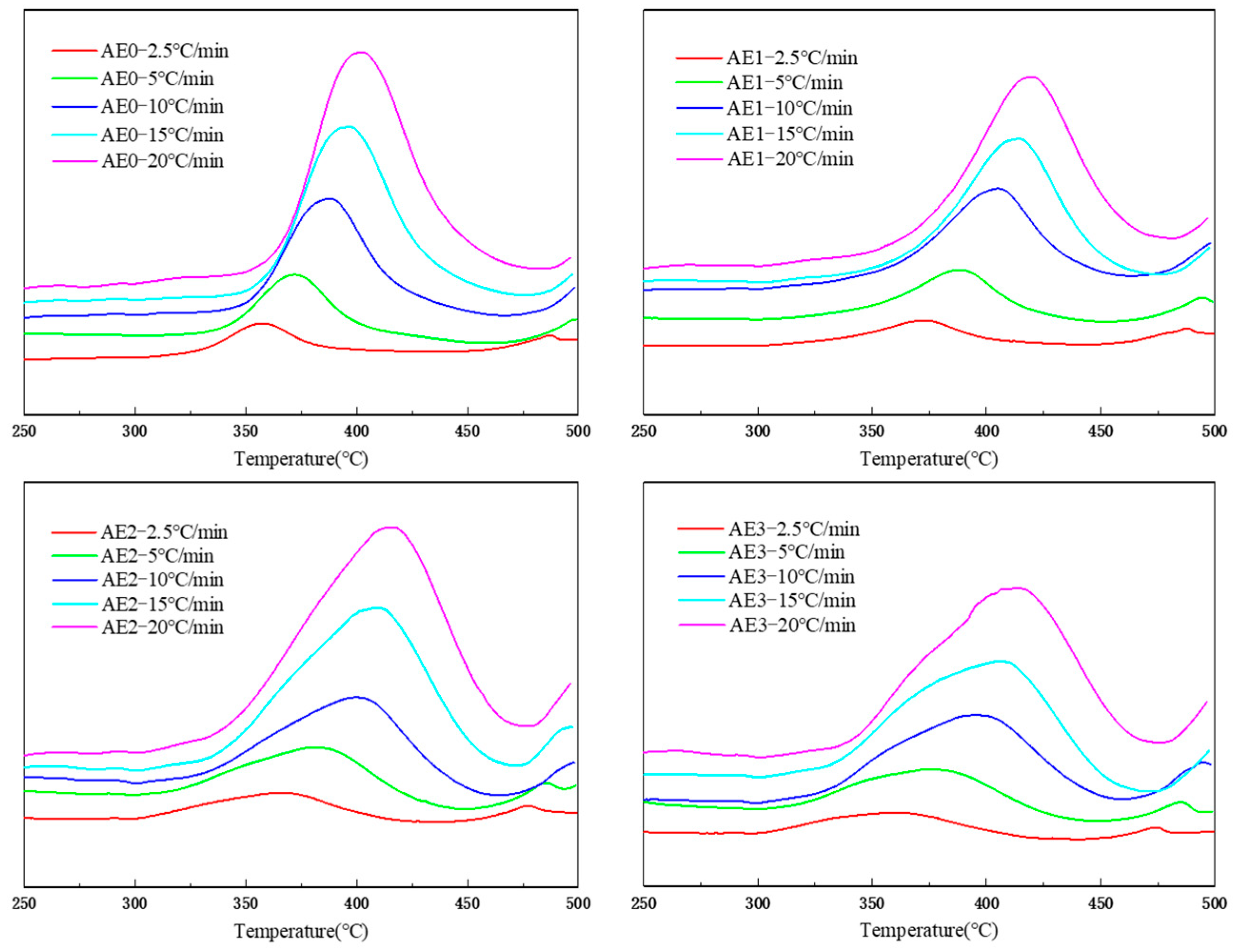

3.2. Epoxy Influence on the Polyimide Curing Kinetics

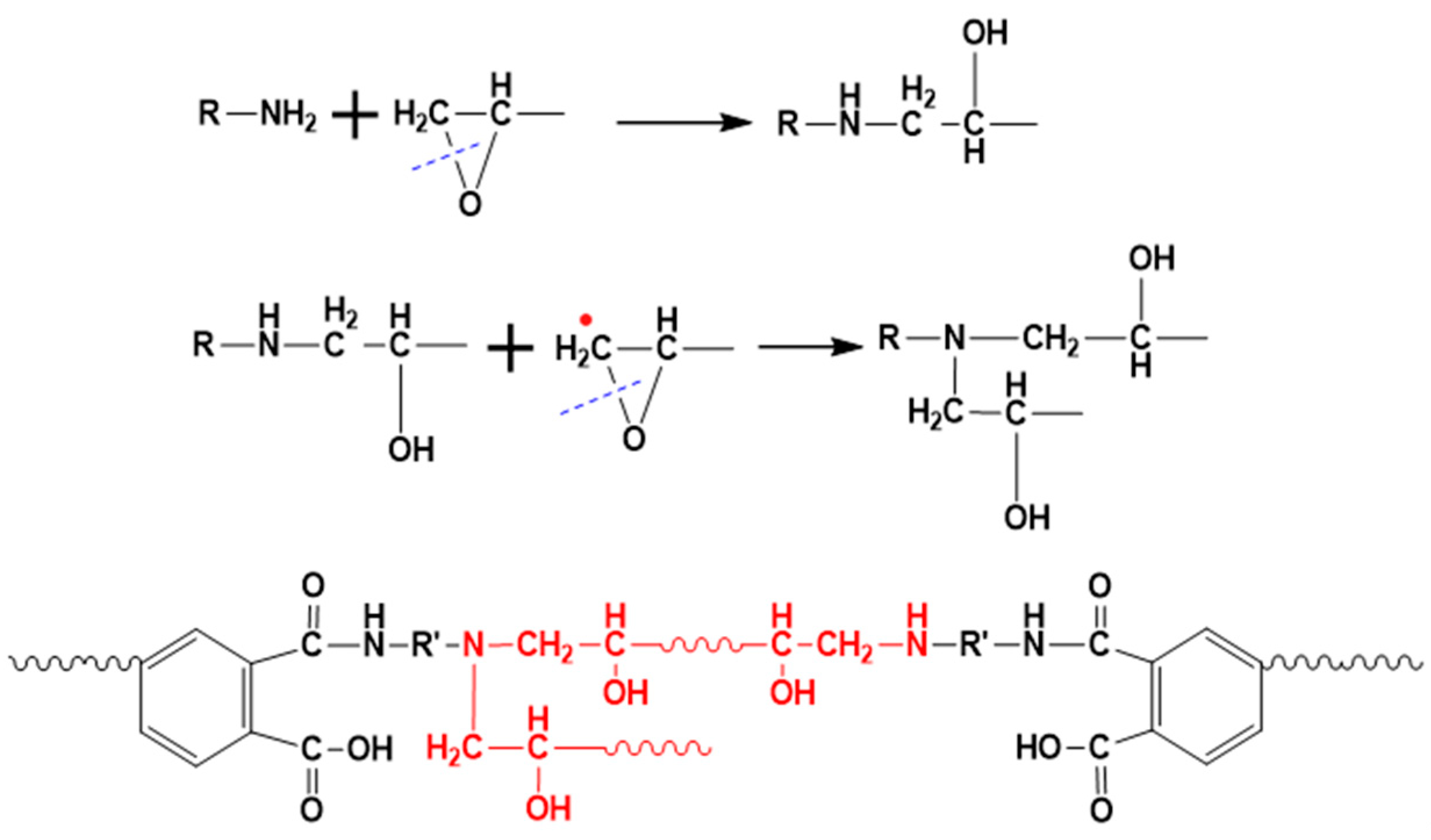

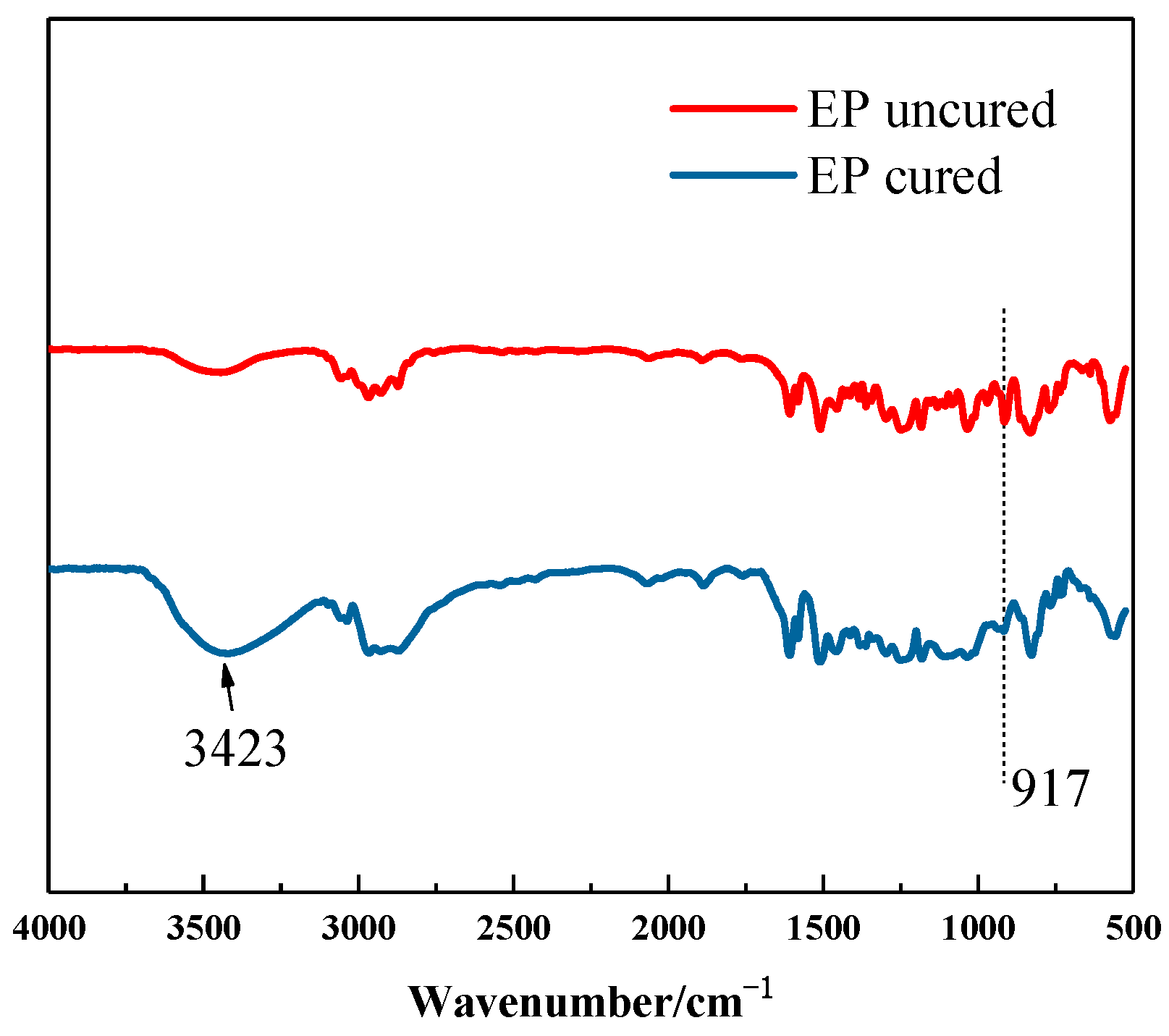

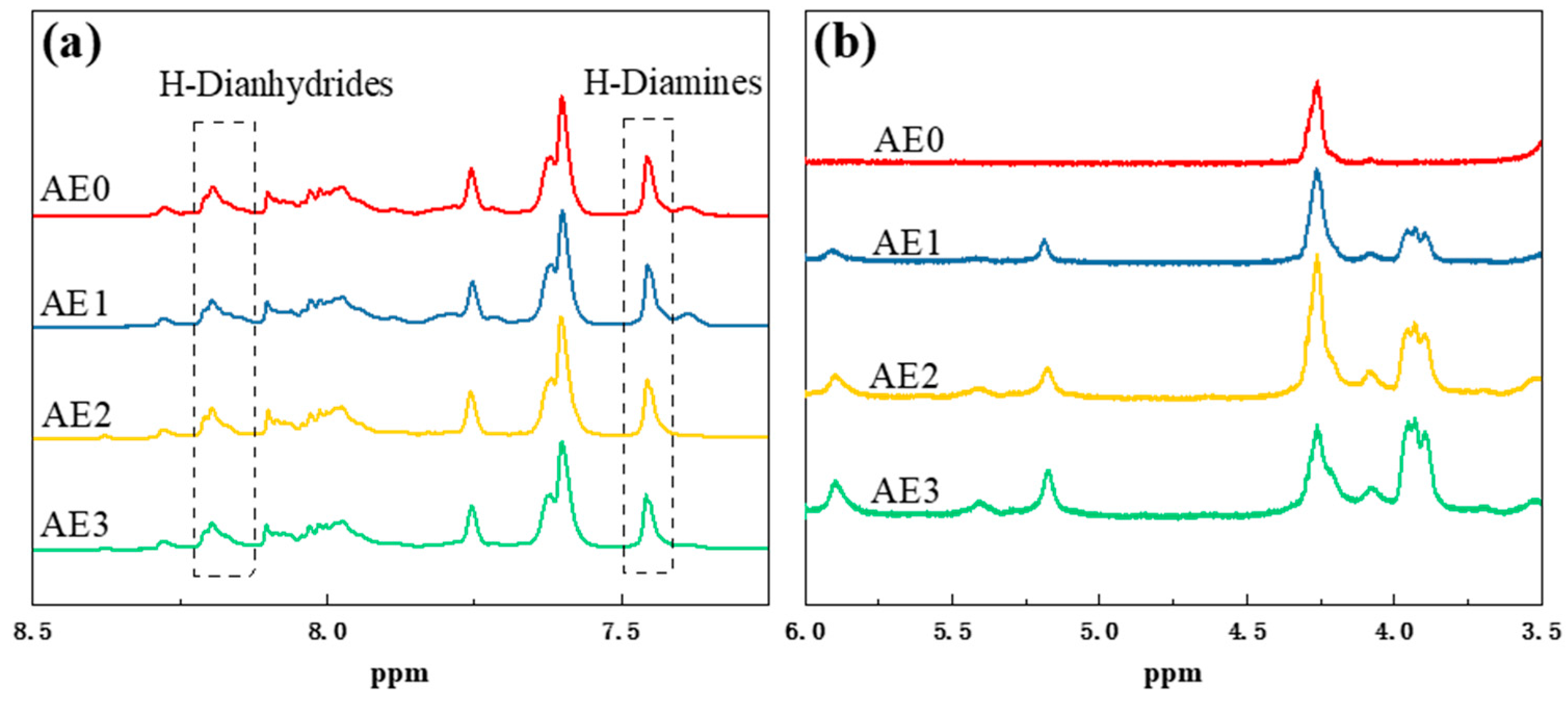

3.3. Structure Characterization of the Polyimide–Epoxy Compound

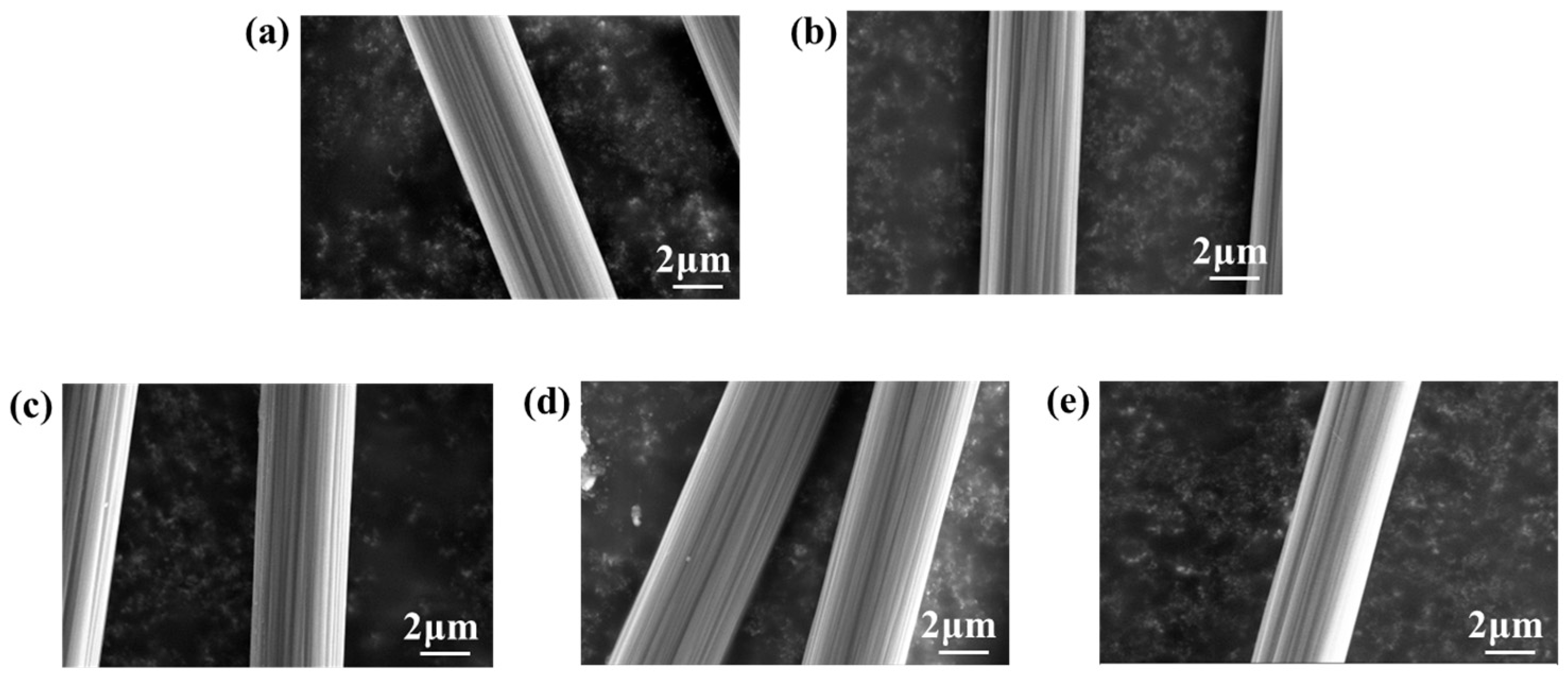

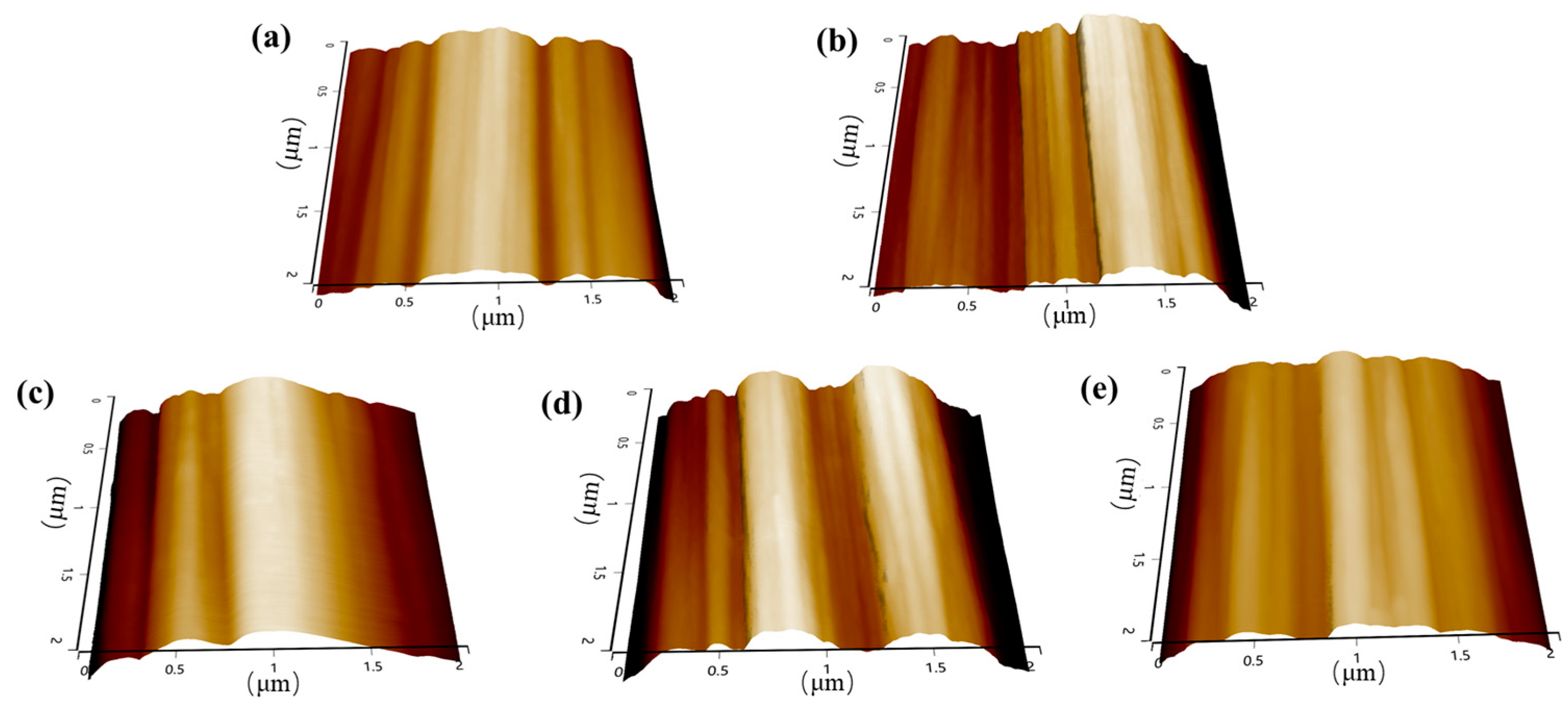

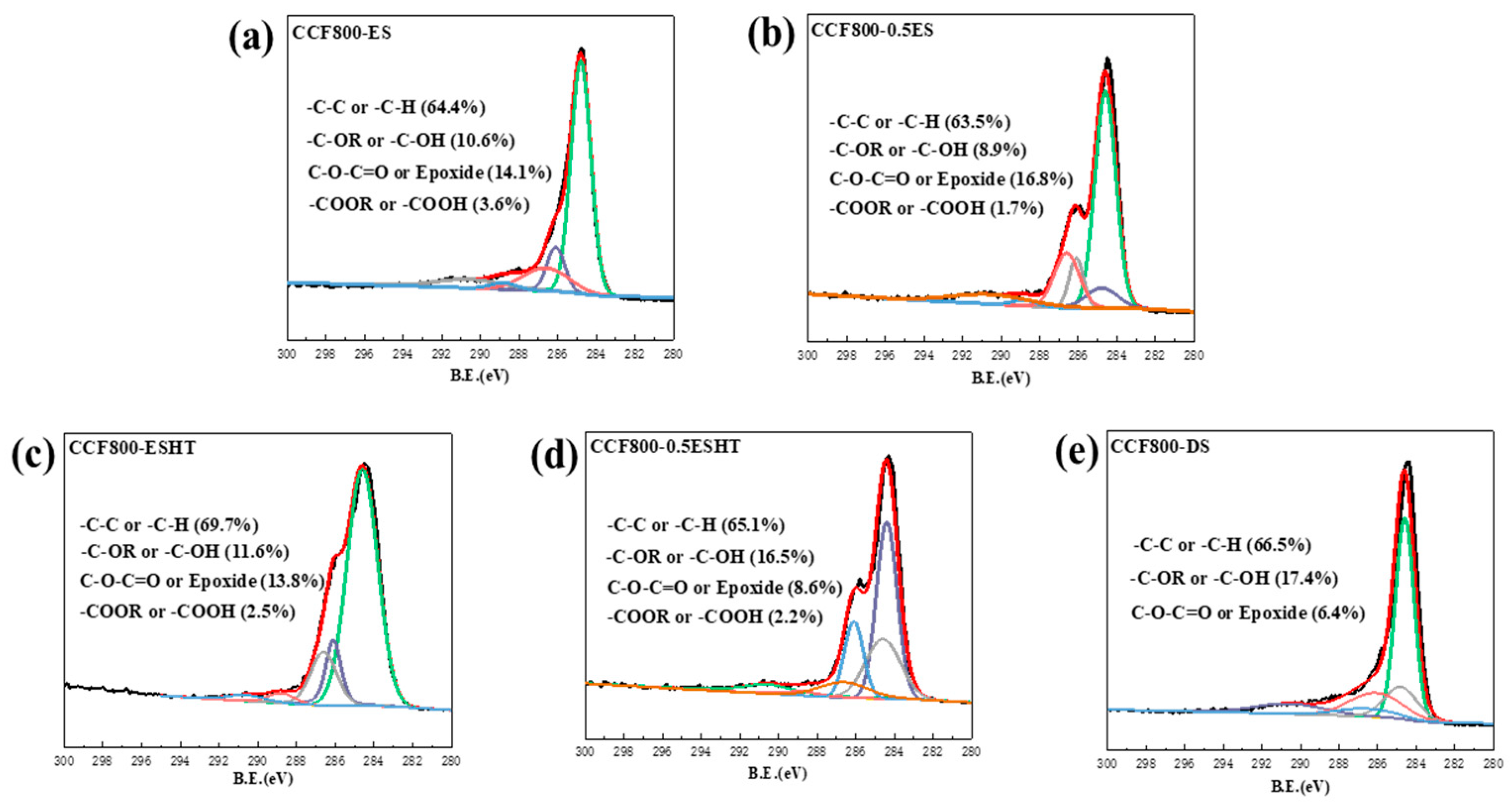

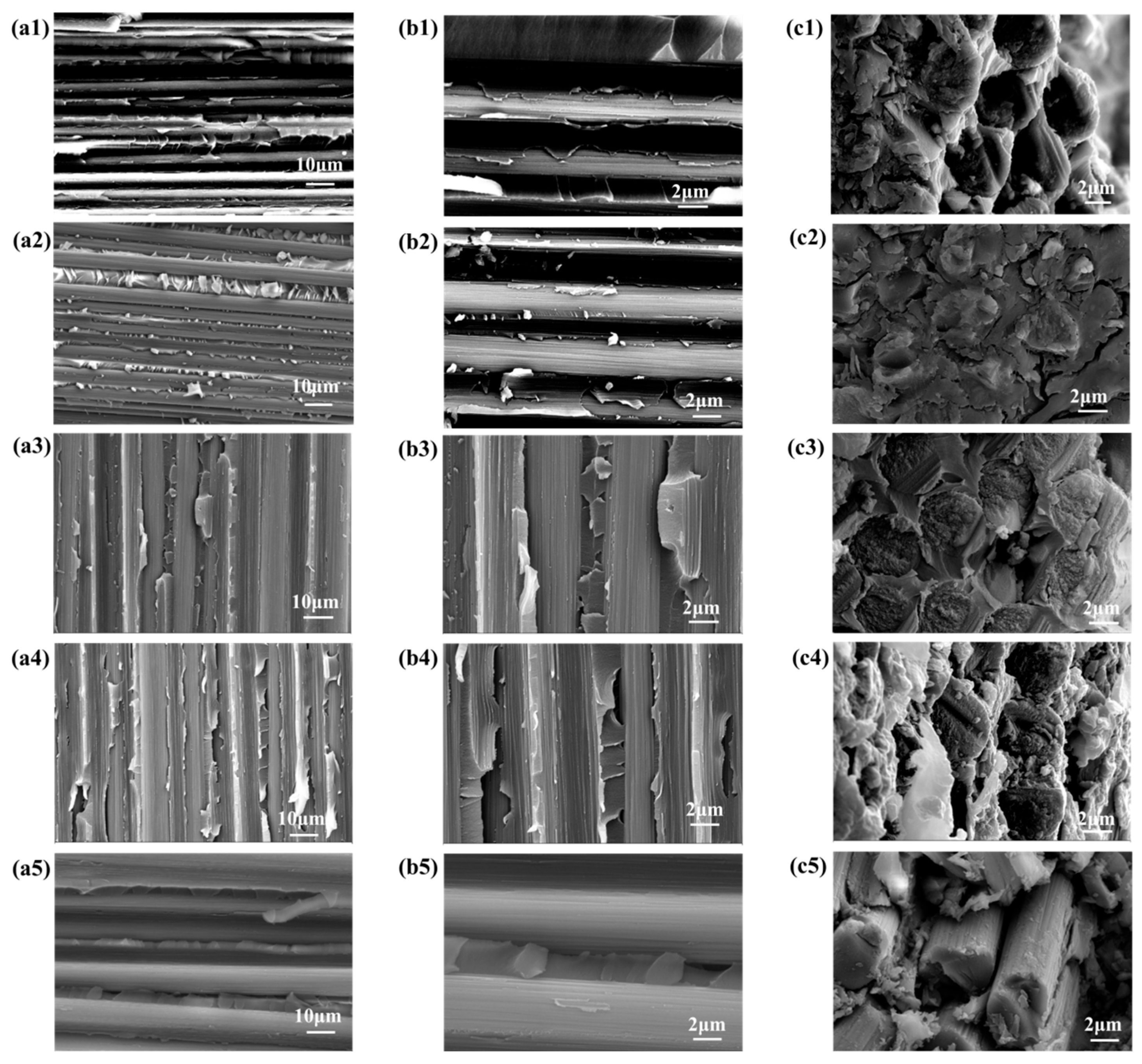

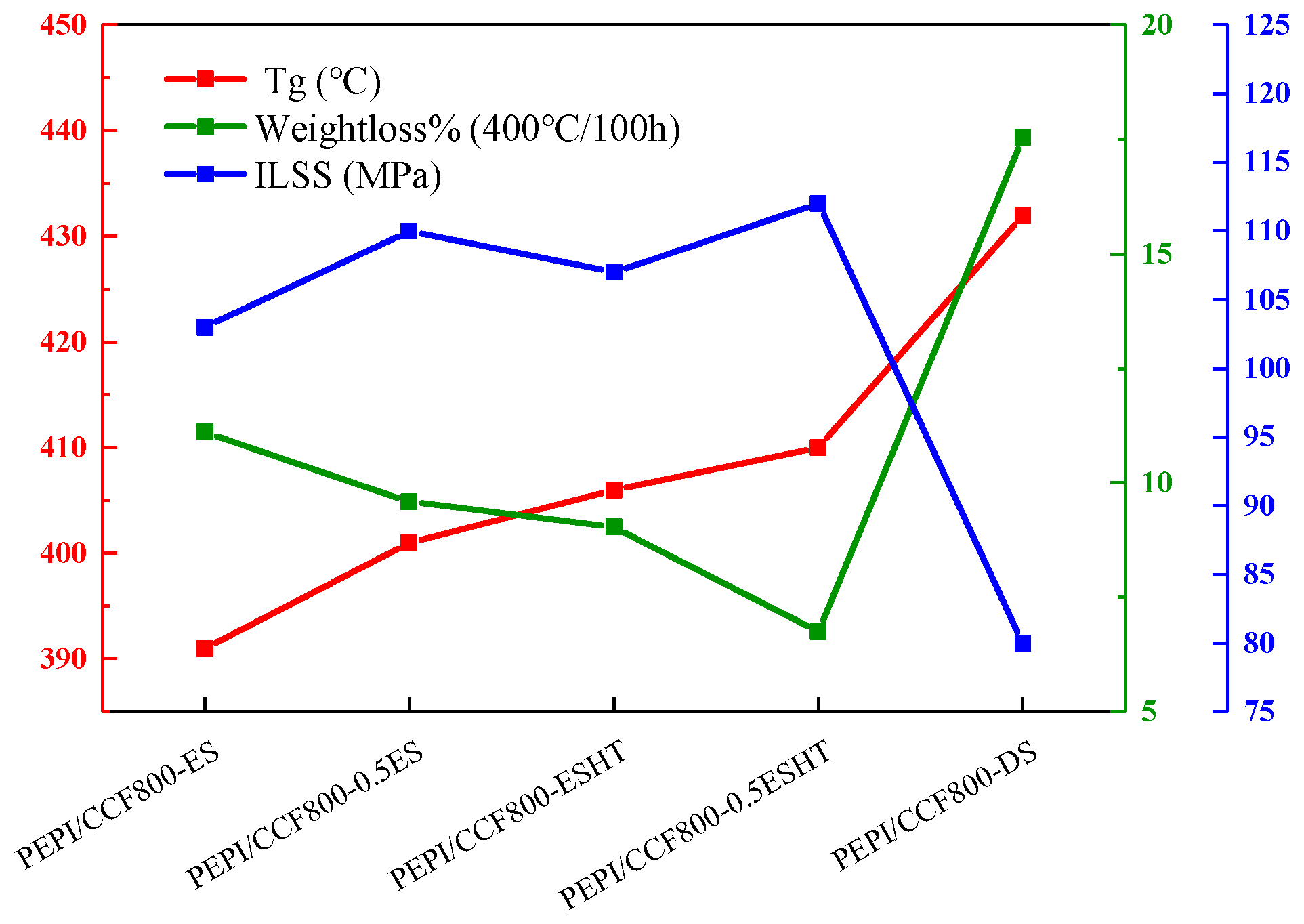

3.4. Strategy to Enhance the Thermal Resistance

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, X.B. Polymer-Matrix Composite Handbook; Chemical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, G. Aero engines lose weight thanks to composites. Reinf. Plast. 2012, 56, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Wang, J.; Ren, Y. Research on high-temperature resistant resin matrix composites of hypersonic aircraft structure. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2228, 012014. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, M. Aerospace looks to composites for solutions. Reinf. Plast. 2017, 61, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Y.; Ji, M. Polyimide matrices for carbon fiber composites. In Advanced Polyimide Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 93–136. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, J.W.; Chen, X.B. Advance in high temperature polyimide resin matrix composites for aeroengine. J. Aeronaut. Mater. 2012, 32, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D. Polyimides as resin matrices for advanced composites. In Polyimides; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1990; pp. 187–226. [Google Scholar]

- Cavano, P.J.; Winters, W.E. Fiber Reinforced PMR Polyimide Composites; TRW Inc.: Cleveland, OH, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Serafini, T.T. PMR polyimide composites for aerospace applications. In Proceedings of the Technical Conference on Polyimides, Ellenville, NY, USA, 10–12 November 1982. NAS 1.15: 83047. [Google Scholar]

- Poveromo, L.M. Polyimide Composites: Application Histories; NASA: Washington, DC, USA; Lewis Research Center High Temp: Cleveland, OH, USA; Polymer Matrix Composites: Cleveland, OH, USA, 1985.

- Bowles, K.J.; Jayne, D.; Leonhardt, T.A.; Bors, D. Thermal Stability Relationships Between PMR-15 Resin and Its Composites; NASA: Hanover, MD, USA, 1993.

- Zhu, W.; Ren, X.; Li, X.; Gu, C.; Liu, Z.; Yan, Z.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, T. Improvement of part-load performance of gas turbine by adjusting compressor inlet air temperature and IGV opening. Front. Energy 2022, 16, 1000–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Yu, J.; Dang, C.; Qin, J.; Jing, W. Performance comparison between closed-Brayton-cycle power generation systems using supercritical carbon dioxide and helium–xenon mixture at ultra-high turbine inlet temperatures on hypersonic vehicles. Energy 2024, 293, 130653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry-Blais, A.; Sivić, S.; Picard, M. Micro-mixing combustion for highly recuperated gas turbines: Effects of inlet temperature and fuel composition on combustion stability and NOx emissions. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2022, 144, 091014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, K.C.; Bowles, K.J.; Papadopoulos, D.S.; DeNise, H.-G.; Linda, M. A High T (sub g) PMR Polyimide Composites (DMBZ-15); NASA: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2000.

- Hutapea, P.; Yuan, F.G. The effect of thermal aging on the Mode-I interlaminar fracture behavior of a high-temperature IM7/LaRC-RP46 composite. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1999, 59, 1271–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.Q.; Wang, X.C.; Hu, A.J.; Zhang, Y.L. Preparation and properties of PMR-II polyimide/chopped quartz fibre composites. High Perform. Polym. 2000, 12, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.D.; Kardos, J.L. Modeling the imidization kinetics of AFR700B polyimide. Polym. Compos. 1997, 18, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.D. OMC Compressor Case; NASA Lewis Research Center: Cleveland, OH, USA, 1997.

- Russell, J.D.; Kardos, J.L. Crosslinking characterization of a polyimide: AFR700B. Polym. Compos. 1997, 18, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hergenrother, P.M.; Smith, J.G., Jr. Chemistry and properties of imide oligomers end-capped with phenylethynylphthalic anhydrides. Polymer 1994, 35, 4857–4864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.H. Processing and Properties of Fiber Reinforced Polymeric Matrix Composites: I. IM7/LARC (TM)-PETI-7 Polyimide Composites; NASA Langley Research Center: Hampton, VA, USA, 1995.

- Veazie, D.R.; Lindsay, J.S.; Siochi, E.J. Effects of resin consolidation on the durability of IM7/PETI-5 composites. Compos. Technol. Res. 2001, 23, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, K.; Collins, T. Mechanical properties of T650-35/AFRPE-4 at elevated temperatures for lightweight aeroshell designs. In Proceedings of the 47th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference, Newport, RI, USA, 1–4 May 2006; p. 2202. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson, P.; Waas, A. T650/AFR-PE-4/FM680-1 mode I critical energy release rate at high temperatures: Experiments and numerical models. In Proceedings of the 48th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference, Honolulu, HA, USA, 23–26 April 2007; p. 2305. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Morgan, R.J. Thermal cure of phenylethynyl-terminated AFR-PEPA-4 imide oligomer and a model compound. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 101, 4446–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vij, V.; Haddad, T.S.; Yandek, G.R.; Ramirez, S.M.; Mabry, J.M. Synthesis of aromatic polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) dianilines for use in high-temperature polyimides. Silicon 2012, 4, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. Durability Characterization of POSS-Based Polyimides and Carbon-Fiber Composites for Air Force Related Applications; Michigan State University: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Seurer, B.; Vij, V.; Haddad, T.; Mabry, J.M.; Lee, A. Thermal transitions and reaction kinetics of polyhederal silsesquioxane containing phenylethynylphthalimides. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 9337–9347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Song, J.; Zhao, G.; Ding, Q. Improving the high temperature tribology of polyimide by molecular structure design and grafting POSS. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2022, 33, 886–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; He, C.; Xiao, Y.; Mya, K.Y.; Dai, J.; Siow, Y.P. Polyimide/POSS nanocomposites: Interfacial interaction, thermal properties and mechanical properties. Polymer 2003, 44, 4491–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, J.E.; Morgan, R.J.; Curliss, D.B. Effect of matrix chemical structure on the thermo-oxidative stability of addition cure poly (imide siloxane) composites. Polym. Compos. 2008, 29, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P2 SI-900HT-Datasheet [R/OL]. Available online: https://proofresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/PROOF-ACD_data_sheet_900HT_update_10-16-15v2-correct.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Krishnamachari, P.; Lou, J.; Sankar, J.; Lincoln, J.E. Characterization of fourth-generation high-temperature discontinuous fiber molding compounds. Int. J. Polym. Anal. Charact. 2009, 14, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paipetis, A.; Galiotis, C. Effect of fibre sizing on the stress transfer efficiency in carbon/epoxy model composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 1996, 27, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Jiao, Y.; Mi, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, D.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, H.; Chen, C. PEEK composites with polyimide sizing SCF as reinforcement: Preparation, characterization, and mechanical properties. High Perform. Polym. 2020, 32, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, H.; Dong, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, J.; Huan, X.; Jia, X.; Ge, L.; Yang, X.; Zu, L.; et al. Revisiting the sequential evolution of sizing agents in CFRP manufacturing to guide cross-scale synergistic optimization of interphase gradient and infiltration. Compos. Part B Eng. 2024, 287, 111825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmani, M.H.; Jony, B.; Gupta, K.; Kondekar, N.; Ramachandran, J.; Arias-Monje, P.J.; Kumar, S. Using a carbon fiber sizing to tailor the interface-interphase of a carbon nanotube-polymer system. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 247, 110284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, X.; Li, X.; Wang, N.; Shen, X.; Song, N.; Xu, T.; Ding, P. Cross-scale optimization of interfacial adhesion and thermal-mechanical performance in carbon fiber-reinforced polyimide composites through sizing agent evolution. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2025, 266, 111174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, S.D.; Emmerson, G.T.; McGrail, P.T.; Robinson, R.M. Thermoplastic sizing of carbon fibres in high temperature polyimide composites. J. Adhes. 1994, 45, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Luo, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Jiang, H. Water-soluble silane terminated polyimide coating for basalt fiber to improve its thermal resistance. Mater. Lett. 2024, 377, 137471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchoslav, J.; Unterweger, C.; Steinberger, R.; Fürst, C.; Stifter, D. Investigation on the thermo-oxidative stability of carbon fiber sizings for application in thermoplastic composites. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2016, 125, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudzinski, S.; Häussler, L.; Harnisch, C.; Mäder, E.; Heinrich, G. Glass fibre reinforced polyamide composites: Thermal behaviour of sizings. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2011, 42, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaw, K.; Jikei, M.; Kakimoto, M.; Imai, Y.; Mochjizuki, A. Adhesion behaviour of polyamic acid cured epoxy. Polymer 1997, 38, 4413–4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agag, T.; Takeichi, T. Synthesis and characterization of epoxy film cured with reactive polyimide. Polymer 1999, 40, 6557–6563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, M.; Okulska-Bożek, M.; Zygmunt, M. Effect of poly (amic acid) and polyimide on the adhesive strength and fracture toughness of epoxy resin. Mater. Sci. 2011, 47, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaw, K.; Kikei, M.; Kakimoto, M.; Imai, Y. Preparation of polyimide-epoxy composites. React. Funct. Polym. 1996, 30, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D7028-07; Standard Test Method for Glass Transition Temperature (DMA Tg) of Polymer Matrix Composites by Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- ASTM D2344; Standard Test Method for Short-Beam Strength of Polymer Matrix Composite Materials and Their Laminates. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- Drzal, L.T.; Rich, M.J.; Koenig, M.F.; Lloyd, P.F. Adhesion of graphite fibers to epoxy matrices: II. The effect of fiber finish. J. Adhes. 1983, 16, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, V.; Drzal, L.T. The temperature dependence of interfacial shear strength for various polymeric matrices reinforced with carbon fibers. J. Adhes. 1992, 37, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, T.G., Jr.; Flory, P.J. Second-order transition temperatures and related properties of polystyrene. I. Influence of molecular weight. J. Appl. Phys. 1950, 21, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocks, J.; Rintoul, L.; Vohwinkel, F.; George, G. The kinetics and mechanism of cure of an amino-glycidyl epoxy resin by a co-anhydride as studied by FT-Raman spectroscopy. Polymer 2004, 45, 6799–6811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.S.; Shah, P.P.; Patel, S.R. Differential scanning calorimetry investigation of curing of bisphenolfurfural resins. Polym. Eng. Sci. 1986, 26, 1186–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Liu, B.; Sun, Q.; Yuan, Z.; Shen, J.; Cheng, R. Cure kinetic study of carbon nanofibers/epoxy composites by isothermal DSC. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2005, 96, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Gu, M.; Jin, Y.; Wang, J. Mechanism and Kinetics of Epoxy-Imidazole Cure Studied with Two Kinetic Methods. Polym. J. 2005, 37, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissinger, H.E. Reaction Kinetics in Differential Thermal Analysis. Anal. Chem. 1957, 29, 1702–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, L.W.; Dynes, P.J.; Kaelble, D.H. Analysis of curing kinetics in polymer composites. J. Polym. Sci. Part C Polym. Lett. 2010, 11, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhang, P.; Li, B.; Sun, M.; Liu, H.; Sun, J.; Zhao, Y.; Bao, J. A water-soluble thermoplastic polyamide acid sizing agents for enhancing interfacial properties of carbon fibre reinforced polyimide composites. Materials 2024, 17, 2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | AE0 | AE1 | AE2 | AE3 | ADE | Epoxy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEPI/g | 44.592 | 44.592 | 44.592 | 44.592 | 44.592 | 0 |

| E54/g | 0 | 0.43 | 1.37 | 1.8 | 1.37 | 1.37 |

| D230/g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.43 | 0.43 |

| Epoxy/(PI + Epoxy) | 0 | 0.955% | 2.98% | 3.88% | 3.88% | 1 |

| Sample | Tg (Tanδ) Actual Measurement | Tg (Tanδ) Theoretical Calculation |

|---|---|---|

| PEPI resin | 441 °C | 441 °C |

| E54/D230 | 101 °C | 101 °C |

| ADE resin | 385 °C | 417 °C |

| PEPI/CCF800 composite | 391 °C | 417 °C |

| Sample | Ea [kJ/mol] | lnA | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| AE0 | 150.74 | 15.58 | 0.9329 |

| AE1 | 150.08 | 14.70 | 0.9310 |

| AE2 | 141.68 | 13.38 | 0.9278 |

| AE3 | 132.96 | 11.90 | 0.9238 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xing, Y.; Ni, H.; Zhang, D.; Li, J.; Chen, X. Strategy Construction to Improve the Thermal Resistance of Polyimide-Matrix Composites Based on Fiber–Resin Compatibility. Materials 2025, 18, 5685. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245685

Xing Y, Ni H, Zhang D, Li J, Chen X. Strategy Construction to Improve the Thermal Resistance of Polyimide-Matrix Composites Based on Fiber–Resin Compatibility. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5685. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245685

Chicago/Turabian StyleXing, Yu, Hongjiang Ni, Daijun Zhang, Jun Li, and Xiangbao Chen. 2025. "Strategy Construction to Improve the Thermal Resistance of Polyimide-Matrix Composites Based on Fiber–Resin Compatibility" Materials 18, no. 24: 5685. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245685

APA StyleXing, Y., Ni, H., Zhang, D., Li, J., & Chen, X. (2025). Strategy Construction to Improve the Thermal Resistance of Polyimide-Matrix Composites Based on Fiber–Resin Compatibility. Materials, 18(24), 5685. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245685