The Effect of Sc and Zr Additions on the Structure, Mechanical, and Corrosion Properties of a High Thermal Conductive Al–3%Zn–3%Ca Alloy

Abstract

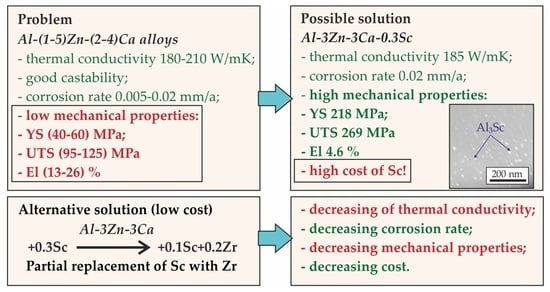

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

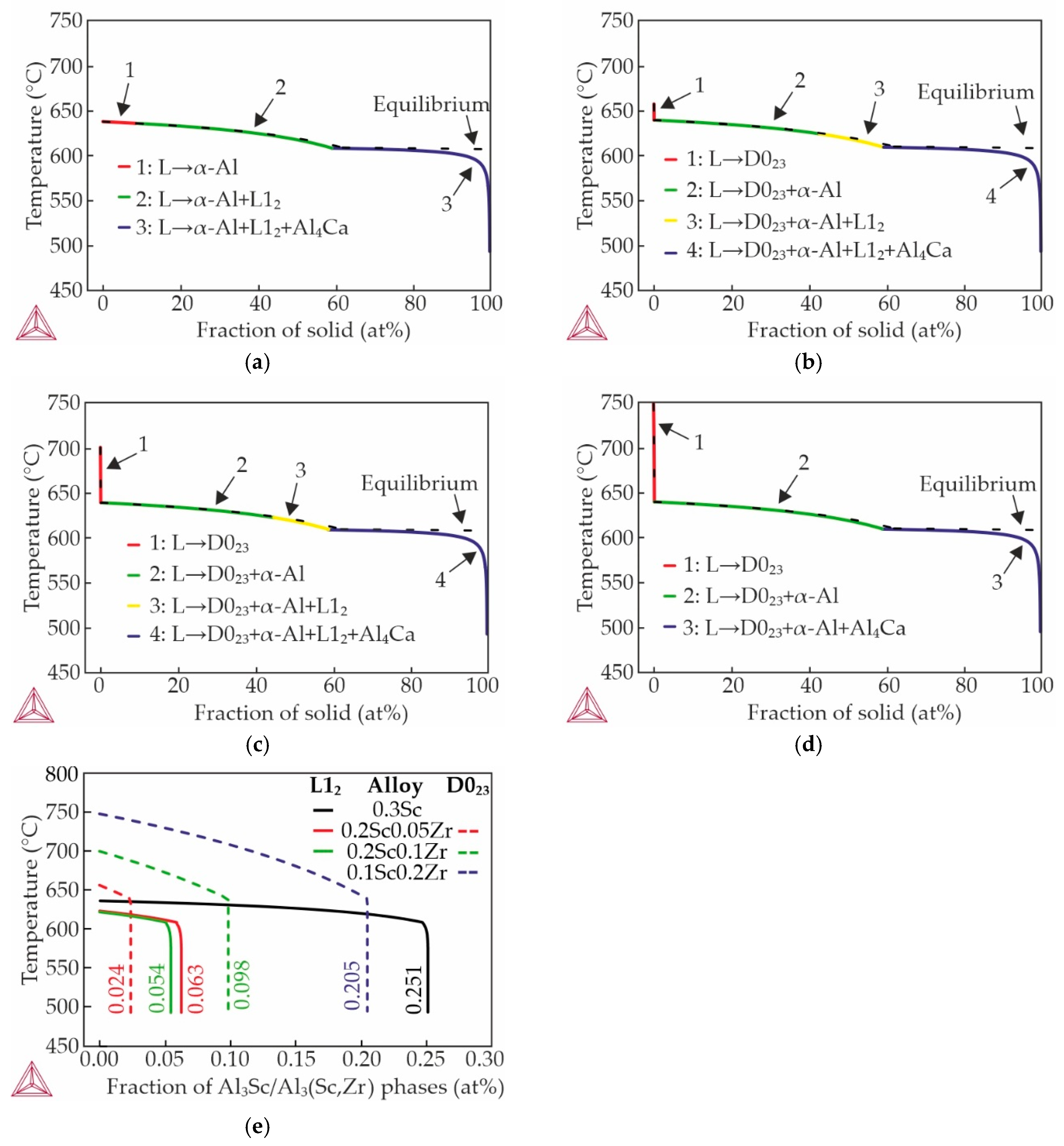

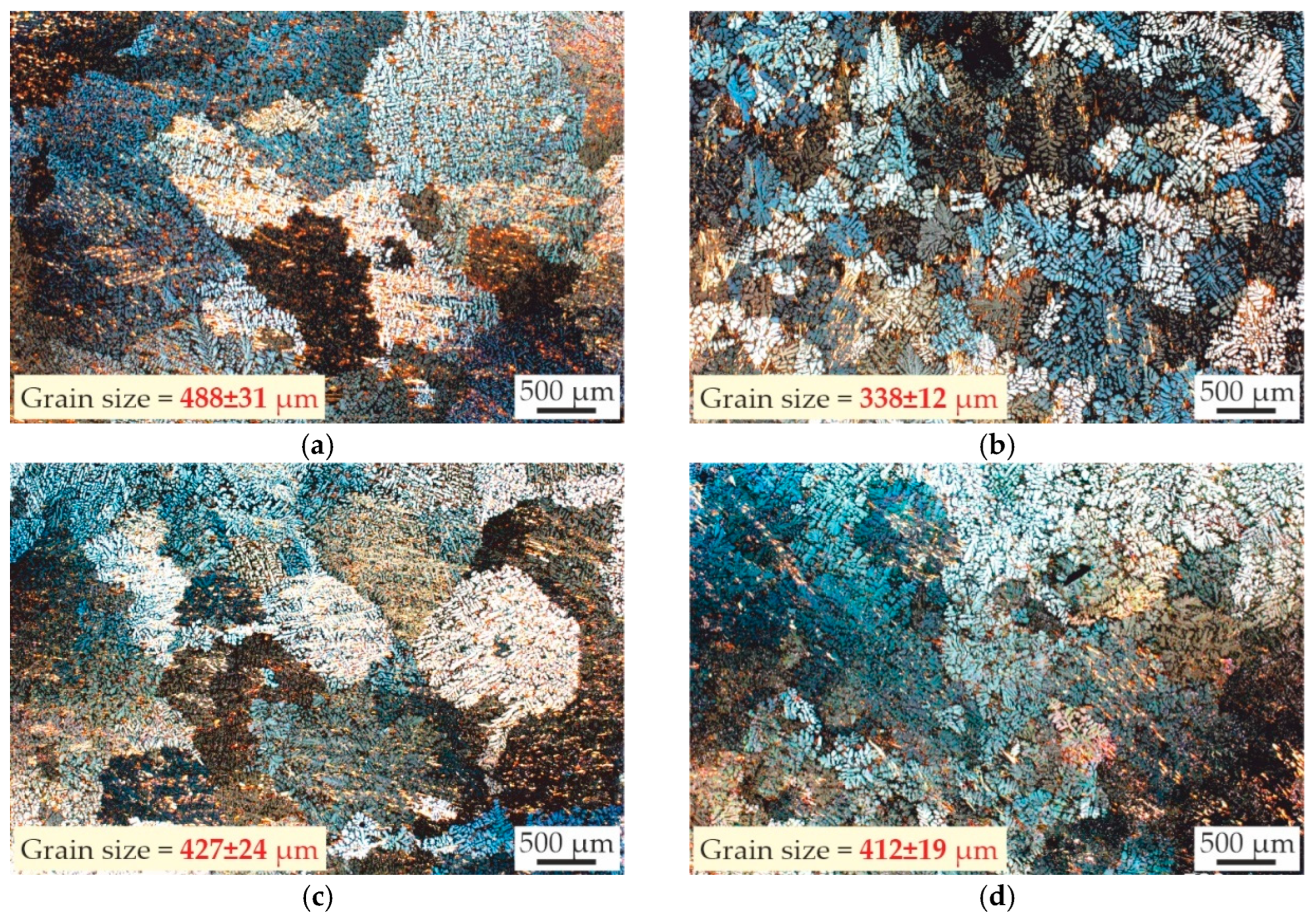

3.1. Effect of Sc and Zr Additions on as-Cast Structure of Al–Zn–Ca Alloys

3.2. Effect of Aging Treatment on Hardness and Thermal Conductivity of Alloys

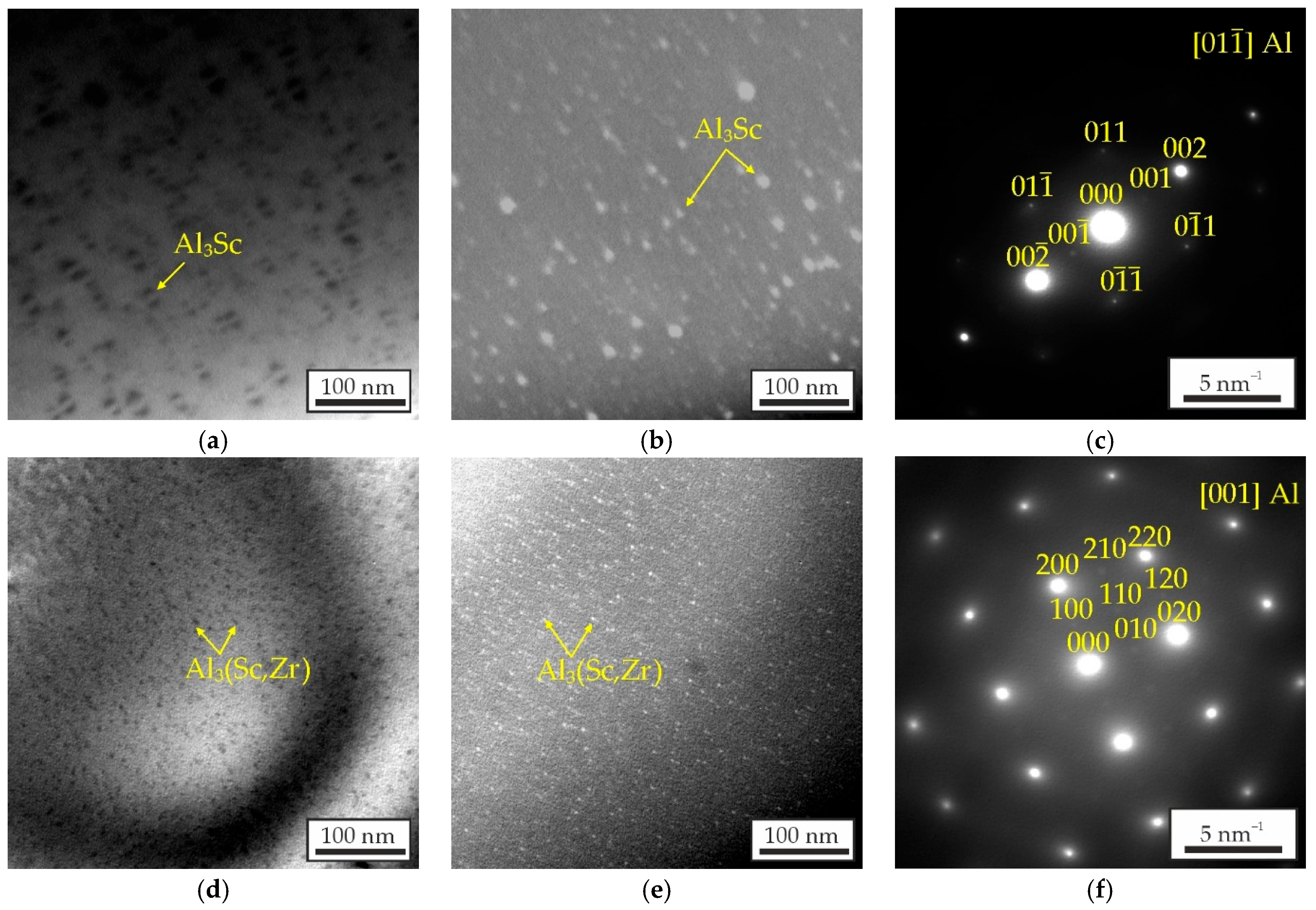

3.3. Mechanical Properties and TEM Analysis of as-Aged Alloys

3.4. Effect of Sc and Zr on Corrosion Properties of as-Aged Alloys

3.5. Thermal Conductivity of Al–3wt%Zn–3wt%Ca–0.3wt%Sc Alloy

4. Conclusions

- The microstructure of the as-cast alloys consists of α-Al dendrites and refined lamellas of α-Al + (Al,Zn)4Ca eutectic. Sc was found to be uniformly distributed throughout the aluminum matrix, while Zr was concentrated in the center of dendritic cells. All alloys demonstrated coarse grain structure, but the addition of Zr lead to a little decrease in the grain size. The minimal grain size of 338 μm was observed for the alloy with 0.2 wt% Sc and 0.05 wt% Zr.

- In the as-cast state, the substitution of scandium with zirconium did not result in a substantial alteration of the alloys’ hardness and was approximately 50 HB. However, this substitution did lead to a decline in the thermal conductivity of the alloys, with a decrease from 167.6 to 158.9 W/mK (calculated via Smith–Palmer equation).

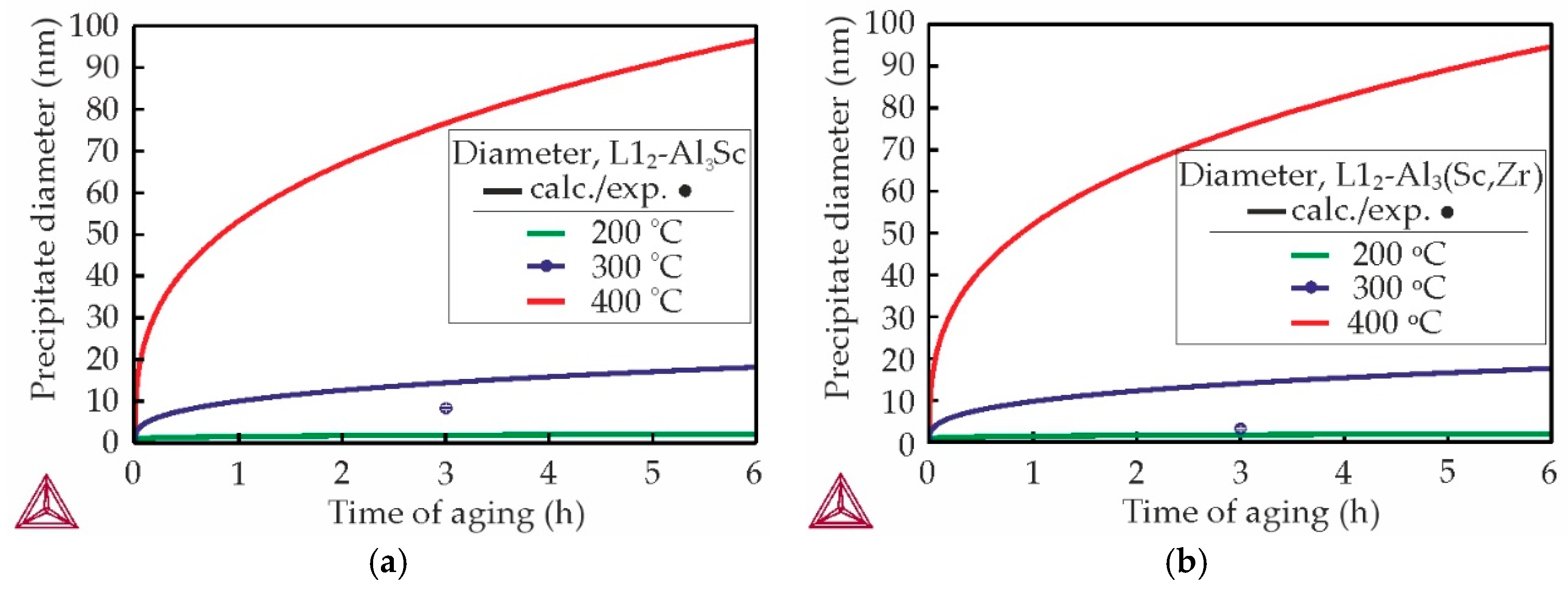

- The most suitable heat treatment regime was determined to be the aging treatment at 300 °C for 3 h. This regime resulted in a substantial enhancement of the alloys hardness to 93 HB and thermal conductivity obtained, via the Smith-Palmer equation, to ~185 W/mK. However, an increase in the Zr content led to a decrease in hardness and thermal conductivity in as-aged alloys.

- The Al–Zn–Ca–Sc–Zr alloys exhibit high mechanical properties in as-aged state due to the precipitation of strengthening Al3Sc/Al3(Sc,Zr) phase during the aging process. However, substituting Sc with Zr results in a decrease in the UTS of the alloys from 269 to 206 MPa and an increase in their El from 4.6 to 7.1%. The highest strength was obtained in the alloy with 0.3% Sc.

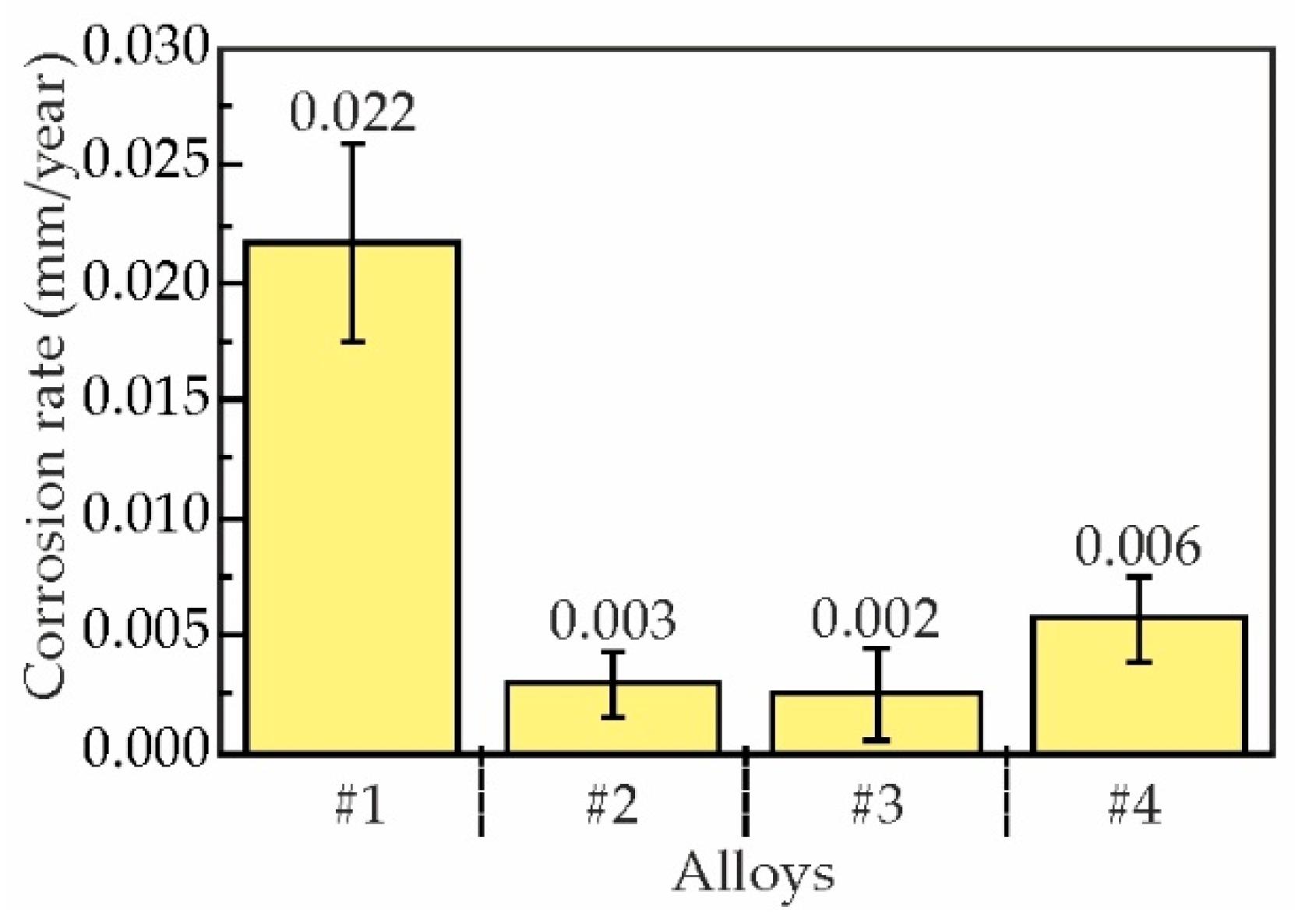

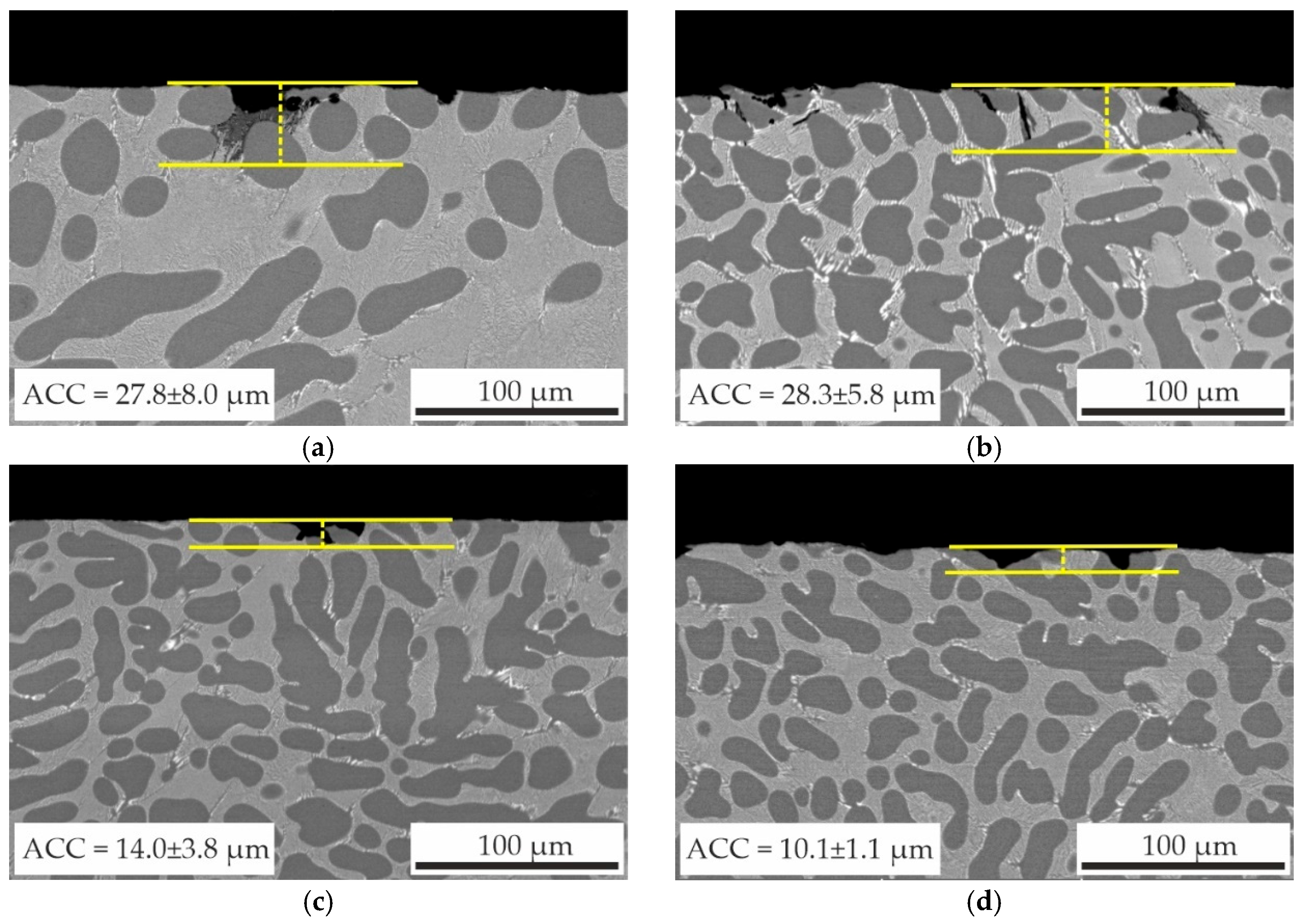

- The immersion corrosion test results demonstrated that replacing Sc with Zr can reduce the corrosion rate of as-aged alloys from 0.022 to 0.002–0.006 mm/year and reduce the average corrosion cavity depth from 27.8 ± 8.0 μm to 10.1 ± 1.1 μm. Electrochemical corrosion testing has demonstrated that the partial substitution of Sc with Zr in alloy compositions enhances the resistance of the alloys to pitting corrosion.

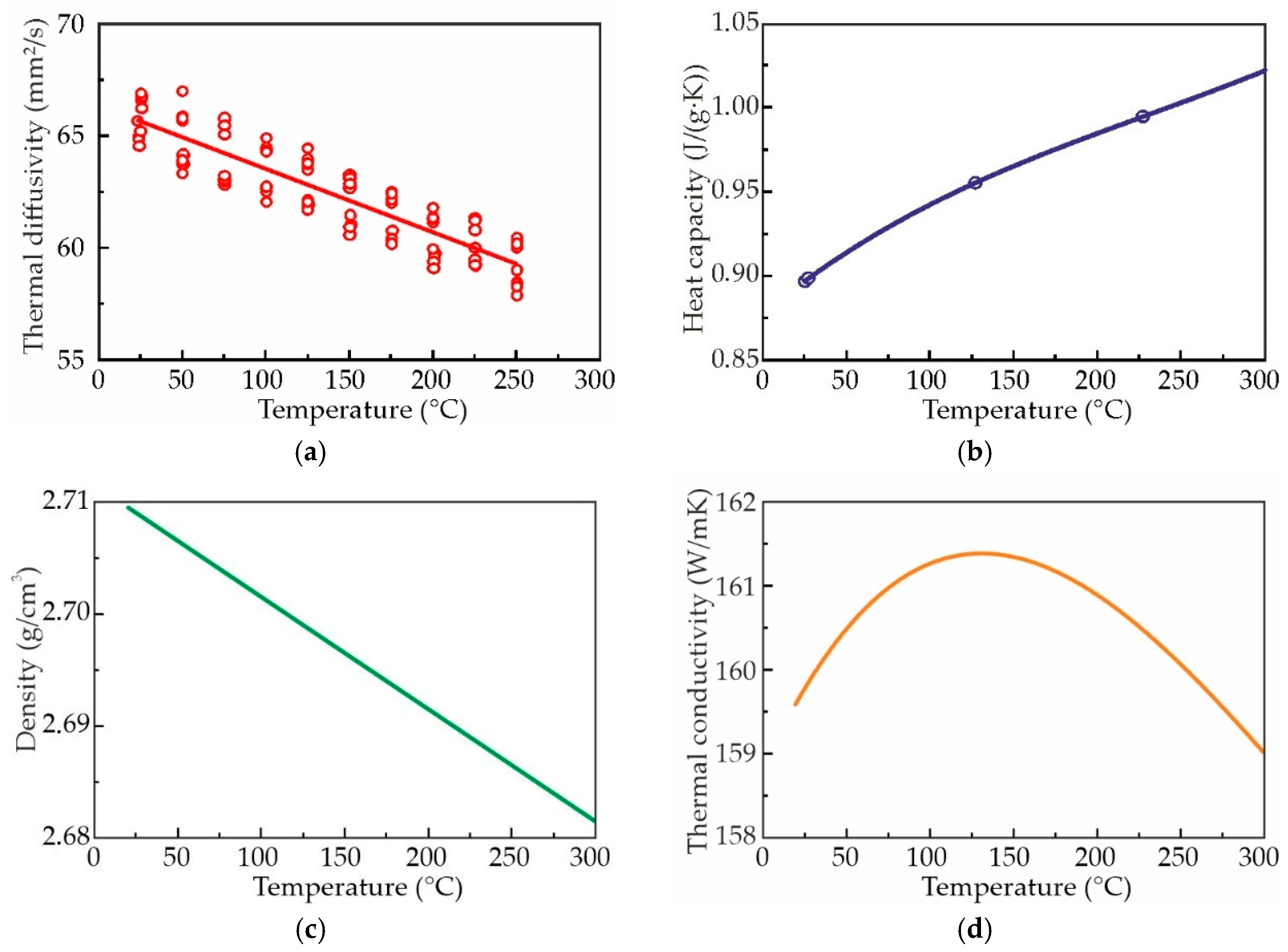

- The thermal conductivity of the AlZn3Ca3Sc0.3 alloy in as-aged condition, which was determined using the thermal diffusivity equation, shows exceptional stability (±1%) across 25–300 °C.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, L.J.B.; Corbin, S.F.; Hexemer, R.L., Jr.; Donaldson, I.W.; Bishop, D.P. Development and Processing of Novel Aluminum Powder Metallurgy Materials for Heat Sink Applications. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2013, 45, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haga, T.; Fuse, H. Die Casting of Lightweight Thin Fin Heat Sink Using Al-25%Si. Metals 2024, 14, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jou, R.Y. Convective Heat Transfer Measurements of Die-Casting Heat Sinks. Key Eng. Mater. 2010, 419, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sce, A.; Caporale, L. High Density Die Casting (HDDC): New Frontiers in the Manufacturing of Heat Sinks. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2014, 525, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Li, Y. Effect of alloying elements on thermal conductivity of aluminum. J. Mater. Res. 2023, 38, 2049–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Akhtar, S.; Wang, P.; He, Z.; Jiao, X.; Ge, S.; Yuan, G.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Thermal Conductivity of Binary Al Alloys with Different Alloying Elements. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 177257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Huang, Y.; Wen, C.; Du, J. Effect of Sr Modification on Microstructure and Thermal Conductivity of Hypoeutectic Al−Si Alloys. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2020, 30, 2879–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.H.; Kim, H.W.; Lee, J.M.; Kim, M.S. A New Approach to the Design of a Low Si-Added Al–Si Casting Alloy for Optimising Thermal Conductivity and Fluidity. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 50, 7271–7281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Hu, S.; Wang, K.; Huang, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Li, W. Effect of Silicon Micro-Alloying on the Thermal Conductivity, Mechanical Properties and Rheological Properties of the Al–5Ni Cast. Int. J. Met. 2024, 18, 3277–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, G.; Zhou, X.; Li, C.; Du, J. Design and Preparation of Al-Fe-Ce Ternary Aluminum Alloys with High Thermal Conductivity. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2022, 32, 1781–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotiadis, S.; Zimmer, A.; Elsayed, A.; Vandersluis, E.; Ravindran, C. High Electrical and Thermal Conductivity Cast Al-Fe-Mg-Si Alloys with Ni Additions. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2020, 51, 4195–4214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nováková, I.; Jelínek, M.; Švec, M. Thermal Conductivity of AlSi10MnMg Alloy in Relation to Casting Technology and Heat Treatment Method. Materials 2024, 17, 5329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessoway, K.; Pillari, L.K.; Bichler, L. Effects of T4 and T7 Heat Treatments on the Electrical Conductivity and Wear Behaviour of A356.2 Aluminum Alloy. Metallogr. Microstruct. Anal. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayani, S.H.; Lee, S.U.; Euh, K.; Lee, J.M.; Cho, Y.H. Effect of As-Cast Microstructure on Precipitation Behavior and Thermal Conductivity of T5-Treated Al7Si0.35Mg Alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 976, 173004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, J.E. Aluminum: Properties and Physical Metallurgy, 1st ed.; ASM: Metals Park, OH, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Chen, S.; Jiao, L.; Shen, W.; Song, Z.; Wang, J.; Nie, Z.; Shcheretskyi, O. Preparation of Graphene Nanoplatelets Reinforced Aluminum Matrix Composites by Friction Stir Processing and Study of Thermal Conductivity and Toughness Properties. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 48, 113606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andilab, B.; Emadi, P.; Sydorenko, M.; Ravindran, C. Influence of GNP Additions on the Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, and Electrical Conductivity of Cast A319 Aluminum Alloy. Int. J. Met. 2024, 18, 3047–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.S.; Zhou, L.; Liu, K.Y.; Liu, Z.Y.; Wang, Q.Z.; Xiao, B.L.; Ma, Z.Y. Finite Element Prediction of the Thermal Conductivity of GNP/Al Composites. Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 2022, 35, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazhenov, V.E.; Koltygin, A.V.; Sung, M.C.; Park, S.H.; Tselovalnik, Y.V.; Stepashkin, A.A.; Rizhsky, A.A.; Belov, M.V.; Belov, V.D.; Malyutin, K.V. Development of Mg–Zn–Y–Zr Casting Magnesium Alloy with High Thermal Conductivity. J. Magnes. Alloys 2021, 9, 1567–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belov, N.A.; Naumova, E.A.; Bazlova, T.A.; Alekseeva, E.V. Structure, Phase Composition, and Strengthening of Cast Al–Ca–Mg–Sc Alloys. Phys. Met. Metallogr. 2016, 117, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumova, E.A. Use of Calcium in Alloys: From Modifying to Alloying. Russ. J. Non-Ferr. Met. 2018, 59, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letyagin, N.V.; Musin, A.F.; Sichev, L.S. New Aluminum-Calcium Casting Alloys Based on Secondary Raw Materials. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 38, 1551–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevorkov, D.; Schmid-Fetzer, R. The Al-Ca System, Part 1: Experimental Investigation of Phase Equilibria and Crystal Structures. Int. J. Mater. Res. 2001, 92, 946–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyskovich, A.A.; Bazhenov, V.E.; Baranov, I.I.; Bautin, V.A.; Sannikov, A.V.; Bazlov, A.I.; Tian, E.I.; Stepashkin, A.A.; Koltygin, A.V.; Belov, V.D. Castability, mechanical, and corrosion properties of Al−Zn−Ca alloys with high thermal conductivity. Trans. Nonferr. Met. Soc. China 2025, 35, 3595–3616. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Q.; Zhang, F.; Wei, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J. Effect of Rare Earth (La, Ce, Nd, Sc) on Strength and Toughness of 6082 Aluminum Alloy. Vacuum 2023, 215, 112333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Han, J.; Li, W.; Wang, J. Study of Rare Earth Element Effect on Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of an Al-Cu-Mg-Si Cast Alloy. Rare Met. 2006, 25, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, V.V. Effect of Scandium on the Structure and Properties of Aluminum Alloys. Met. Sci. Heat Treat. 2003, 45, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.A.; Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Pan, D.; Su, H.; Du, X.; Li, P.; Wu, Y. Effect of Sc on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of As-Cast Al–Mg Alloys. Mater. Des. 2016, 90, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.; Puga, H.; Barbosa, J.; Pinto, A.M.P. The Effect of Sc Additions on the Microstructure and Age Hardening Behaviour of As Cast Al–Sc Alloys. Mater. Des. 2012, 42, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, A.F.; Prangnell, P.B.; McEwen, R.S. The Solidification Behaviour of Dilute Aluminium–Scandium Alloys. Acta Mater. 1998, 46, 5715–5732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Xiao, W.; Zheng, R.; Hanada, S.; Yamagata, H.; Ma, C. The Synergic Effects of Sc and Zr on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Al–Si–Mg Alloy. Mater. Des. 2015, 88, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbord, B.; Lefebvre, W.; Danoix, F.; Hallem, H.; Marthinsen, K. Three Dimensional Atom Probe Investigation on the Formation of Al3(Sc,Zr)-Dispersoids in Aluminium Alloys. Scr. Mater. 2004, 51, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.; Mo, W.; Ouyang, Z.; Tang, C.; Luo, B.; Bai, Z. Mechanical Properties and Corrosion Behaviors of (Sc, Zr) Modified Al-Cu-Mg Alloy. Mater. Charact. 2023, 196, 112619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheil, E. Bemerkungen zur Schichtkristallbildung. Int. J. Mater. Res. 1942, 34, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, J.O.; Helander, T.; Höglund, L.; Shi, P.; Sundman, B. Thermo-Calc & DICTRA, Computational Tools for Materials Science. Calphad 2002, 26, 273–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemens, P.G.; Williams, R.K. Thermal Conductivity of Metals and Alloys. Int. Met. Rev. 1986, 31, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirier, D.R.; Mcbride, E. A Thermal conductivities of hypoeutectic AI-Cu alloys during solidification and cooling. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1997, 224, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, M.W. NIST-JANAF Thermochemical Tables. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1998, 28, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM G110-92; Standard Practice for Evaluating Intergranular Corrosion Resistance of Heat Treatable Aluminum Alloys by Immersion in Sodium Chloride + Hydrogen Peroxide Solution. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2003.

- ASTM G1-03; Standard Practice for Preparing, Cleaning, and Evaluating Corrosion Test Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2011.

- Belov, N.A.; Naumova, E.A.; Akopyan, T.K. Effect of Calcium on Structure, Phase Composition and Hardening of Al-Zn-Mg Alloys Containing up to 12 wt.% Zn. Mater. Res. 2015, 18, 1384–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohar, A.K.; Mondal, B.; Rafaja, D.; Klemm, V.; Panigrahi, S.C. Microstructural Investigations on As-Cast and Annealed Al–Sc and Al–Sc–Zr Alloys. Mater. Charact. 2009, 60, 1387–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Zhang, L.; Wu, G.; Zhang, X.; Chen, A.; Tao, J. Effects of Sc Addition on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Cast Al-3Li-1.5Cu-0.15Zr Alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 680, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.C.; Zhang, X.Y.; Huang, Y.C. Understanding Grain Refinement of Sc Addition in a Zr Containing Al-Zn-Mg-Cu Aluminum Alloy from Experiments and First-Principles. Intermetallics 2020, 123, 106823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Wu, Y. Effects of Sc(Zr) on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of As-Cast Al–Mg Alloys. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2017, 33, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Tan, P.; Quan, X.; Liu, Z.; Yi, D.; Wang, B. The Effect of Sc Addition on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of As-Cast Zr-Containing Al-Cu Alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 909, 164686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlach, M.; Čížek, J.; Kodetová, V.; Kekule, T.; Lukáč, F.; Cieslar, M.; Kudrnová, H.; Bajtošová, L.; Leibner, M.; Harcuba, P.; et al. Annealing Effects in Cast Commercial Aluminium Al–Mg–Zn–Cu(–Sc–Zr) Alloys. Met. Mater. Int. 2021, 27, 995–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toropova, L.S.; Eskin, D.G.; Kharakterova, M.L.; Dobatkina, T.V. Advanced Aluminum Alloys Containing Scandium: Structure and Properties; Routledge: London, UK, 1998; 188p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, C.; Watanabe, D.; Monzen, R. Coarsening Behavior of Al3Sc Precipitates in an Al–Mg–Sc Alloy. Mater. Trans. 2006, 47, 2285–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbord, B.; Hallem, H.; Røyset, J.; Marthinsen, K. Thermal Stability of Al3(Scx,Zr1−x)-Dispersoids in Extruded Aluminium Alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 475, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandersluis, E.; Lombardi, A.; Ravindran, C.; Bois-Brochu, A.; Chiesa, F.; MacKay, R. Factors Influencing Thermal Conductivity and Mechanical Properties in 319 Al Alloy Cylinder Heads. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2015, 648, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, R.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, X. A High-Strength, Ductile Al-0.35Sc-0.2Zr Alloy with Good Electrical Conductivity Strengthened by Coherent Nanosized-Precipitates. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2017, 33, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanivel, S.; Kuehmann, C.; Stucki, J.R.; Filip, E.; Edwards, P. Aluminum Alloys for Die Casting. International Patent WO2020/028730A1, 6 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mondolfo, L.F. Aluminum Alloys: Structure and Properties; Butterworth-Heinemann: London, UK, 1976; 971p. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, K.; Li, M.; Wang, S.; Chen, X. Effect of Zr Addition on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of As-Cast Al-Mg-Mn-Sc Alloys. Int. J. Met. 2025, 19, 2881–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, C.B.; Murray, J.L.; Seidman, D.N. Temporal Evolution of the Nanostructure of Al(Sc,Zr) Alloys: Part I—Chemical Compositions of Al3(Sc1−xZrx) Precipitates. Acta Mater. 2005, 53, 5401–5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.W.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, M.H.; Lee, S.H. Microstructure and Corrosion Characteristics According to the Si Content of Al-Ca-Si Alloys. Sci. Adv. Mater. 2022, 14, 1249–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, M.K.; Birbilis, N.; Buchheit, R.G.; Bovard, F. Investigating Localized Corrosion Susceptibility Arising from Sc Containing Intermetallic Al3Sc in High Strength Al-Alloys. Scr. Mater. 2007, 56, 995–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wloka, J.; Virtanen, S. Influence of Scandium on the Pitting Behaviour of Al–Zn–Mg–Cu Alloys. Acta Mater. 2007, 55, 6666–6672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M. Microstructures and Corrosion Resistances of Hypoeutectic Al-6.5Si-0.45Mg Casting Alloy with Addition of Sc and Zr. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 276, 125321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlova, N.A.; Nokhrin, A.V.; Chuvil’deev, V.N.; Shandria, Y.S.; Bobrov, A.A.; Chegurov, M.K. The Effect of Sc:Zr Ratio on the Corrosion Resistance of Cast Al–Mg Alloys. Phys. Met. Metallogr. 2024, 125, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Alloy | Element Content (wt%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | Zn | Ca | Sc | Zr | |

| AlZn3Ca3Sc0.3 | Bal. | 3.09 | 2.87 | 0.32 | – |

| AlZn3Ca3Sc0.2Zr0.05 | Bal. | 3.13 | 2.99 | 0.20 | 0.06 |

| AlZn3Ca3Sc0.2Zr0.1 | Bal. | 3.09 | 2.82 | 0.17 | 0.11 |

| AlZn3Ca3Sc0.1Zr0.2 | Bal. | 3.29 | 2.93 | 0.12 | 0.23 |

| Points | Element Content (wt%) | Phase/Structure Constituents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | Zn | Ca | Sc | Zr | ||

| 1 | Bal. | 1.11 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 0.30 ± 0.08 | α-Al |

| 2 | Bal. | 10.62 ± 2.40 | 13.44 ± 3.88 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | α-Al + (Al,Zn)4Ca |

| Specimen Designation | TYS (MPa) | UTS (MPa) | El (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlZn3Ca3Sc0.3 | 217.5 ± 5.8 | 269.0 ± 6.9 | 4.6 ± 1.0 |

| AlZn3Ca3Sc0.2Zr0.05 | 195.2 ± 1.5 | 250.7 ± 2.0 | 4.5 ± 1.0 |

| AlZn3Ca3Sc0.2Zr0.1 | 180.9 ± 4.8 | 235.3 ± 6.6 | 5.1 ± 2.2 |

| AlZn3Ca3Sc0.1Zr0.2 | 137.2 ± 5.4 | 206.3 ± 6.1 | 7.1 ± 2.0 |

| Specimen Designation | OCP (V) | Ecorr (V) | Epit (V) | ∆Epassive (V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlZn3Ca3Sc0.3 | –0.950 | –1.17 | –0.934 | 0.190 |

| AlZn3Ca3Sc0.2Zr0.05 | –0.946 | –1.21 | –0.930 | 0.236 |

| AlZn3Ca3Sc0.2Zr0.1 | –0.950 | –1.18 | –0.925 | 0.209 |

| AlZn3Ca3Sc0.1Zr0.2 | –0.950 | –1.19 | –0.907 | 0.253 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lyskovich, A.; Bazhenov, V.; Baranov, I.; Gorshenkov, M.; Voropaeva, O.; Stepashkin, A.; Doroshenko, V.; Barkov, R.Y.; Rustemov, S.; Koltygin, A. The Effect of Sc and Zr Additions on the Structure, Mechanical, and Corrosion Properties of a High Thermal Conductive Al–3%Zn–3%Ca Alloy. Materials 2025, 18, 5680. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245680

Lyskovich A, Bazhenov V, Baranov I, Gorshenkov M, Voropaeva O, Stepashkin A, Doroshenko V, Barkov RY, Rustemov S, Koltygin A. The Effect of Sc and Zr Additions on the Structure, Mechanical, and Corrosion Properties of a High Thermal Conductive Al–3%Zn–3%Ca Alloy. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5680. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245680

Chicago/Turabian StyleLyskovich, Anastasia, Viacheslav Bazhenov, Ivan Baranov, Mikhail Gorshenkov, Olga Voropaeva, Andrey Stepashkin, Vitaliy Doroshenko, Ruslan Yu. Barkov, Shevket Rustemov, and Andrey Koltygin. 2025. "The Effect of Sc and Zr Additions on the Structure, Mechanical, and Corrosion Properties of a High Thermal Conductive Al–3%Zn–3%Ca Alloy" Materials 18, no. 24: 5680. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245680

APA StyleLyskovich, A., Bazhenov, V., Baranov, I., Gorshenkov, M., Voropaeva, O., Stepashkin, A., Doroshenko, V., Barkov, R. Y., Rustemov, S., & Koltygin, A. (2025). The Effect of Sc and Zr Additions on the Structure, Mechanical, and Corrosion Properties of a High Thermal Conductive Al–3%Zn–3%Ca Alloy. Materials, 18(24), 5680. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245680