Influence of Printing Orientation on Tensile Strength and Surface Characterization of a Steel-Powder-Reinforced Thermoplastic Composite Manufactured by FDM Technology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- (a)

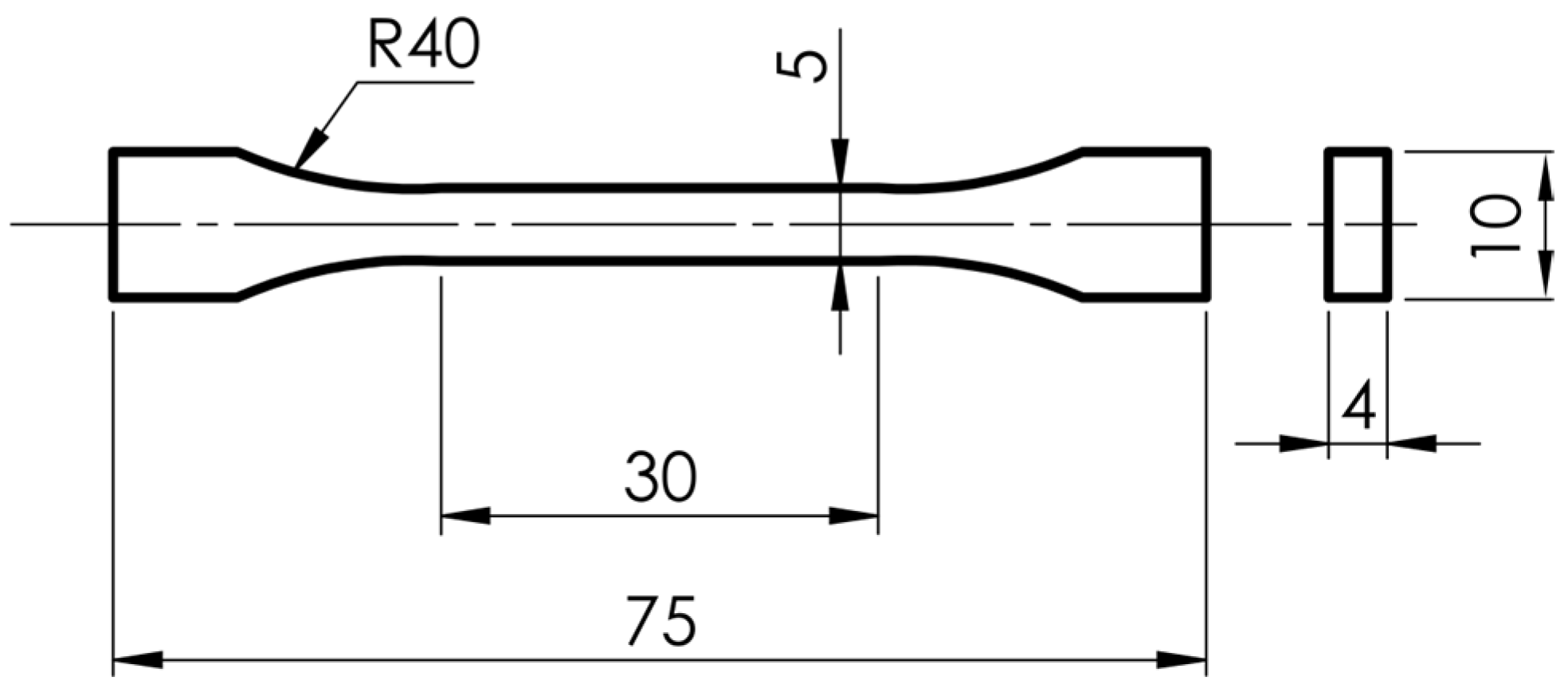

- S1—samples for surface geometric structure analysis and static tensile testing according to ISO 527 (1BA), as shown in Figure 1;

- (b)

- S2—cylinders with a diameter of 40 mm and a height of 6 mm intended for surface wettability measurements.

3. Results

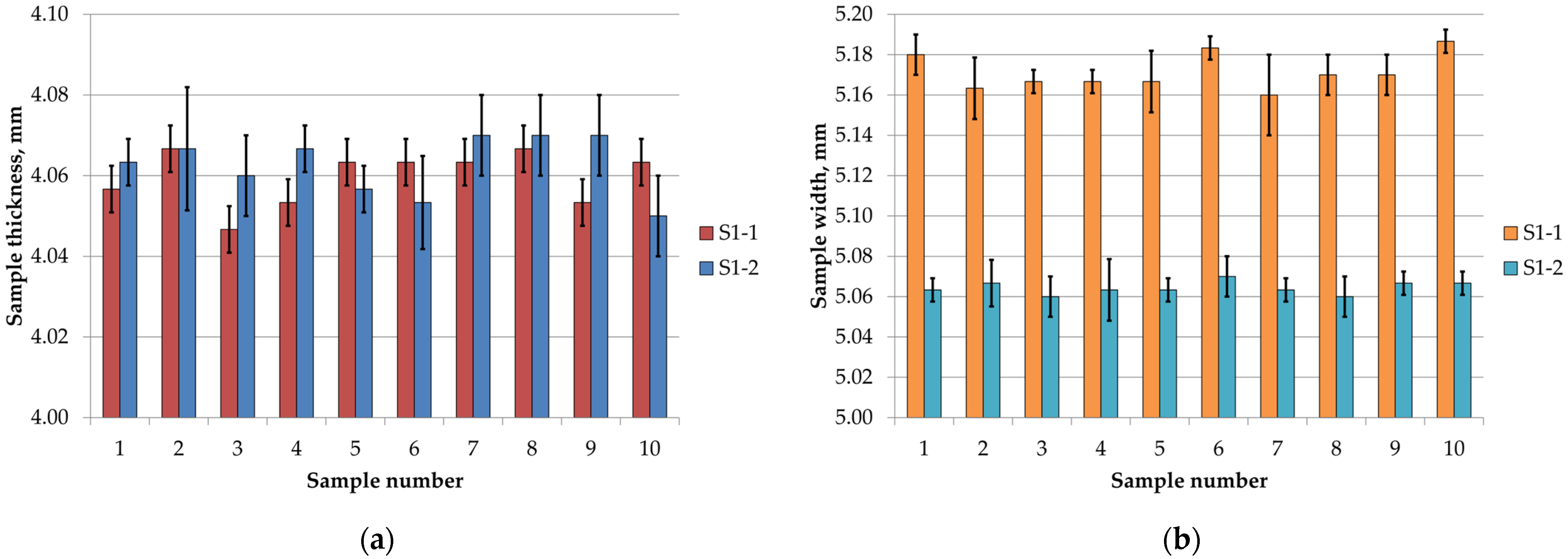

3.1. Measurement of Sample Cross-Sections

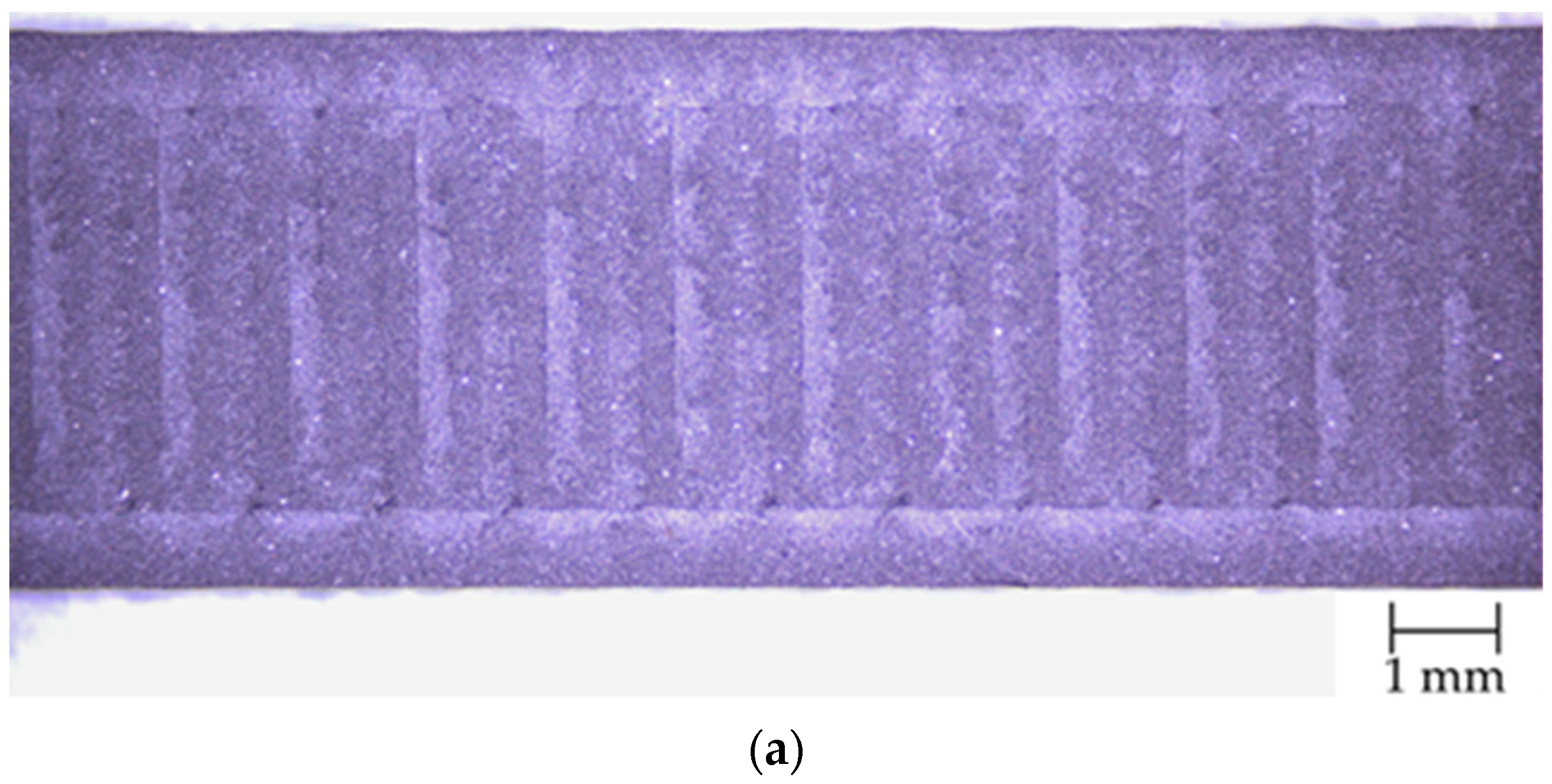

3.2. Microscopic Observations

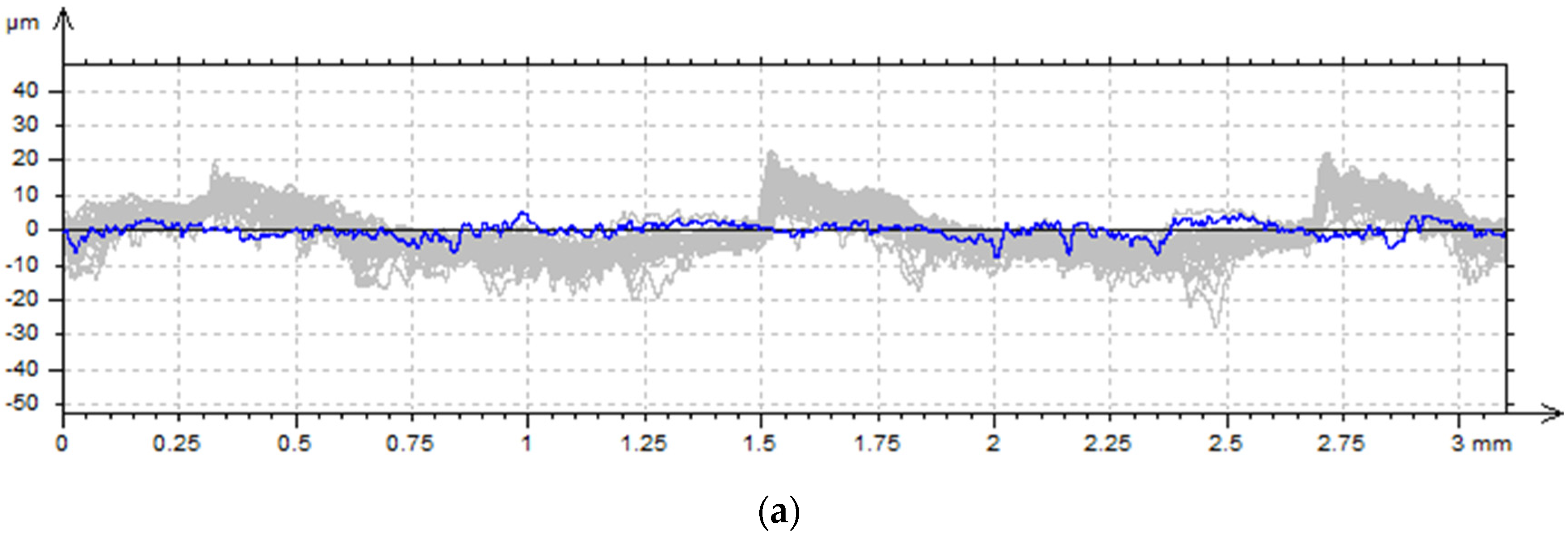

3.3. Contact Profilometer Measurement

3.4. Tensile Test

3.5. Wettability Angle Measurement

3.6. SEM Observations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- -

- The build orientation significantly influences the surface structure, topography, and tensile strength of the thermoplastic composite with steel powder filler;

- -

- Top-layer surfaces exhibit more uniform topography compared to the side-layer surfaces, which results from the nature of material deposition during the FDM process;

- -

- Side-layer surfaces are characterized by higher height parameters (Pp, Pv, Pz, Pt) and a more heterogeneous topography, which is typical of the stair-step effect inherent to layer-by-layer printing;

- -

- Tensile strength is markedly higher in the 0° orientation (average 27.24 MPa) compared to the 90° orientation (average 8.58 MPa), confirming the pronounced mechanical anisotropy arising from the build direction;

- -

- Both orientations exhibit hydrophobic behavior, with surfaces perpendicular to the build layers (90°) being more hydrophobic due to their stepped topography, while parallel layers show relatively higher wettability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wickramasinghe, S.; Do, T.; Tran, P. FDM-Based 3D Printing of Polymer and Associated Composite: A Review on Mechanical Properties, Defects and Treatments. Polymers 2020, 12, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzindziora, A.; Sułowski, M.; Dzienniak, D. Application of Composite Filament with the Addition of Metallic Powders in 3D Printing. Mater. Sci. Forum 2023, 1081, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanon, M.M.; Alshammas, Y.; Zsidai, L. Effect of Print Orientation and Bronze Existence on Tribological and Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed Bronze/PLA Composite. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 108, 553–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memiş, M.; Akgümüş Gök, D. Development of Fe-Reinforced PLA-Based Composite Filament for 3D Printing: Process Parameters, Mechanical and Microstructural Characterization. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2025, 16, 103279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, P.; Bazan, A.; Bulicz, M. Effect of 3D Printing Orientation on the Accuracy and Surface Roughness of Polycarbonate Samples. Machines 2025, 13, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buj-Corral, I.; Domínguez-Fernández, A.; Durán-Llucià, R. Influence of Print Orientation on Surface Roughness in Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) Processes. Materials 2019, 12, 3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozior, T.; Bochnia, J. The Influence of Printing Orientation on Surface Texture Parameters in Powder Bed Fusion Technology with 316L Steel. Micromachines 2020, 11, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrusa, J.; Meier, B.; Grünbacher, G.; Waldhauser, W.; Eckert, J. Surface Topography and Biocompatibility of cp–Ti Grade 2 Fabricated by Laser-Based Powder Bed Fusion: Influence of Printing Orientation and Surface Treatments. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2023, 25, 2201073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, H.; Kim, J.-H. Static and Dynamic Contact Angle Measurements Using a Custom-Made Contact Angle Goniometer. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2023, 37, 4117–4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, C.D.; Hendrickson-Stives, A.K.; Kuhn, S.L.; Jackson, J.B.; Keating, C.D. Designing and 3D Printing an Improved Method of Measuring Contact Angle in the Middle School Classroom. J. Chem. Educ. 2021, 98, 1997–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingman, J.; Dymond, M. Fused Filament Fabrication and Water Contact Angle Anisotropy: The Effect of Layer Height and Raster Width on the Wettability of 3D Printed Polylactic Acid Parts. Chem. Data Collect. 2022, 40, 100884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lou, Y.; Hong, J.; Huang, G.; Liu, M. Predicting the Surface Contact Angle Based on Real-Time Temperature and Pressure Sintering Principles in the Fused Deposition Modeling Process. Mater. Des. 2025, 254, 114126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Sathish, T.; Makki, E.; Giri, J. Experimental Study on Mechanical Properties of FDM 3D Printed Polylactic Acid Fabricated Parts Using Response Surface Methodology. AIP Adv. 2024, 14, 035125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eryıldız, M. Effect of Build Orientation on Mechanical Behaviour and Build Time of FDM 3D-Printed PLA Parts: An Experimental Investigation. Eur. Mech. Sci. 2021, 5, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashruffi, M.A.N.; Ismail, K.I.; Yap, T.C. The Effect of Printing Orientation on the Mechanical Properties of FDM 3D Printed Parts. In Enabling Industry 4.0 Through Advances in Manufacturing and Materials; Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, K.M.; O’Brien, S.; Bischoff, A.; Parmigiani, J.; Roach, D.J. Influence of 3D Printing Parameters on ULTEM 9085 Mechanical Properties Using Experimentation and Machine Learning. Npj Adv. Manuf. 2025, 1, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, S.; Palani, G.; Kanakaraj, A.; Shanmugam, V.; Veerasimman, A.; Gądek, S.; Korniejenko, K.; Marimuthu, U. Metal and Polymer Based Composites Manufactured Using Additive Manufacturing—A Brief Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Gutierrez, J.; Cano, S.; Schuschnigg, S.; Kukla, C.; Sapkota, J.; Holzer, C. Additive Manufacturing of Metallic and Ceramic Components by the Material Extrusion of Highly-Filled Polymers: A Review and Future Perspectives. Materials 2018, 11, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIB METAL. Product Data Sheet (PDS); AIB METAL: Knurów, Poland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- AIB METAL. Safety Data Sheet (SDS); AIB METAL: Knurów, Poland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- AIB METAL. Technical Data Sheet (TDS); AIB METAL: Knurów, Poland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 527-1:2019; Plastics—Determination of Tensile Properties—Part 1: General Principles. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- ISO 178:2019; Plastics—Determination of flexural properties. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- ISO 179-1:2023; Plastics—Determination of Charpy Impact Properties—Part 1: Non-Instrumented Impact Test. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- ISO 1183:2019; Plastics—Methods for Determining the Density of Non-Cellular Plastics. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- ISO 11357:2023; Plastics—Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Bochnia, J.; Blasiak, M.; Kozior, T. A Comparative Study of the Mechanical Properties of FDM 3D Prints Made of PLA and Carbon Fiber-Reinforced PLA for Thin-Walled Applications. Materials 2021, 14, 7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruse, R.E.; Simion, C.; Bondrea, I. Geometrical and Dimensional Deviations of Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) Additive-Manufactured Parts. Metrology 2024, 4, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Omari, A.; Ouballouch, A.; Nassraoui, M. Optimising surface roughness, dimensional accuracy and printing time of FDM PETG parts using statistical methods and artificial neural network. Arch. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 133, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saharudin, M.S.; Hajnys, J.; Kozior, T.; Gogolewski, D.; Zmarzły, P. Quality of Surface Texture and Mechanical Properties of PLA and PA-Based Material Reinforced with Carbon Fibers Manufactured by FDM and CFF 3D Printing Technologies. Polymers 2021, 13, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brăileanu, P.I.; Mocanu, M.-T.; Dobrescu, T.G.; Pascu, N.E.; Dobrotă, D. Structure and Texture Synergies in Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) Polymers: A Comparative Evaluation of Tribological and Mechanical Properties. Polymers 2025, 17, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; Shi, J.; Sun, L.; Lei, W. Effects of Printing Parameters on Properties of FDM 3D Printed Residue of Astragalus/Polylactic Acid Biomass Composites. Molecules 2022, 27, 7373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.A.; Charoo, M.S.; Haq, M.I.U. Mechanical Performance of 3D Printed Functionally Graded PETG: An Experimental Investigation. Next Mater. 2025, 9, 101093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Test Method | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Tensile strength XY | ISO 527-1 [22] | 35 +/− 2 MPa |

| Tensile strength ZX | ISO 527-1 | 19 +/− 2 MPa |

| Elastic modulus | ISO 527-1 | 1.5 +/− 0.1 GPa |

| Tensile yield strain | ISO 527-1 | 5.1 +/− 0.1% |

| Flexural strength | ISO 178 [23] | 66 +/− 2 MPa |

| Flexural deflection | ISO 178 | 9.0 +/− 0.1 mm |

| Charpy notched impact strength | ISO 179-1 [24] | 6 +/− 1 kJ/m2 |

| Density | ISO 1183 [25] | 4 g/cm3 |

| Glass transition temperature | ISO 11357 [26] | 81 °C |

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Layer Height | 0.12 | mm |

| Wall loops | 2 | - |

| Infill pattern | Linear | - |

| Infill density | 100 | % |

| Nozzle temperature | 245 | °C |

| Bed temperature | 80 | °C |

| Print speed | 80 | mm/s |

| First layer height | 0.30 | mm |

| Sample Designation | Number of Repetitions | Orientation |

|---|---|---|

| S1-1 | 10 | 0° |

| S1-2 | 10 | 90° |

| S2-1 | 5 | 0° |

| S2-2 | 5 | 90° |

| Parameter | Mean Value | Standard Deviation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1-1 Top | S1-1 Side | S1-2 Side | S1-1 Top | S1-1 Side | S1-2 Side | |

| Pp, µm | 17.234 | 34.101 | 24.252 | 3.971 | 2.677 | 3.678 |

| Pv, µm | 15.729 | 37.383 | 27.329 | 3.392 | 3.715 | 1.588 |

| Pz, µm | 32.963 | 71.484 | 51.581 | 6.118 | 4.138 | 3.799 |

| Pc, µm | 14.465 | 31.328 | 29.918 | 3.740 | 1.217 | 0.667 |

| Pt, µm | 32.963 | 71.484 | 51.581 | 6.118 | 4.138 | 3.799 |

| Pa, µm | 5.087 | 11.685 | 8.546 | 1.020 | 0.477 | 0.223 |

| Pq, µm | 6.237 | 14.400 | 10.399 | 1.181 | 0.562 | 0.304 |

| Psk | 0.347 | 0.052 | −0.341 | 0.354 | 0.130 | 0.087 |

| Pku | 2.831 | 2.541 | 2.671 | 0.578 | 0.133 | 0.119 |

| Psm, mm | 0.394 | 0.166 | 0.121 | 0.129 | 0.015 | 0.004 |

| Parameter | Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| S1-1 Top | S1-1 Side | S1-2 Side | |

| Sq, µm | 7.682 | 14.497 | 14.141 |

| Ssk | 0.343 | 0.042 | −0.842 |

| Sku | 2.993 | 2.579 | 4.280 |

| Sp, µm | 23.715 | 39.647 | 36.820 |

| Sv, µm | 32.170 | 45.182 | 66.169 |

| Sz, µm | 55.885 | 84.829 | 102.990 |

| Sa, µm | 6.124 | 11.749 | 10.983 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szczygieł, P.; Radoń-Kobus, K. Influence of Printing Orientation on Tensile Strength and Surface Characterization of a Steel-Powder-Reinforced Thermoplastic Composite Manufactured by FDM Technology. Materials 2025, 18, 5656. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245656

Szczygieł P, Radoń-Kobus K. Influence of Printing Orientation on Tensile Strength and Surface Characterization of a Steel-Powder-Reinforced Thermoplastic Composite Manufactured by FDM Technology. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5656. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245656

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzczygieł, Paweł, and Krystyna Radoń-Kobus. 2025. "Influence of Printing Orientation on Tensile Strength and Surface Characterization of a Steel-Powder-Reinforced Thermoplastic Composite Manufactured by FDM Technology" Materials 18, no. 24: 5656. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245656

APA StyleSzczygieł, P., & Radoń-Kobus, K. (2025). Influence of Printing Orientation on Tensile Strength and Surface Characterization of a Steel-Powder-Reinforced Thermoplastic Composite Manufactured by FDM Technology. Materials, 18(24), 5656. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245656