Application of Physical and Quantum-Chemical Characteristics of Epoxy-Containing Diluents for Wear-Resistant Epoxy Compositions

Abstract

1. Introduction

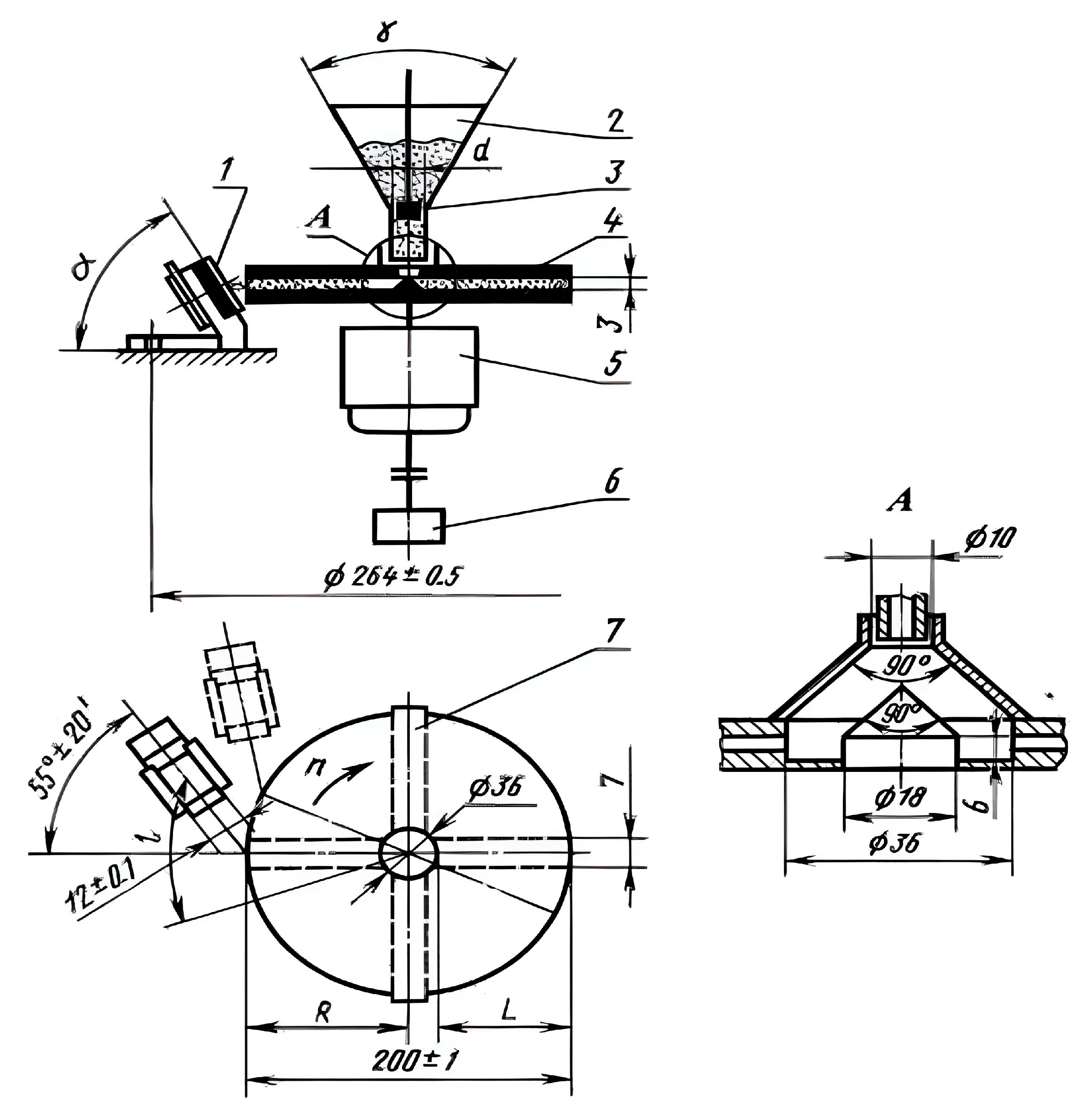

2. Materials and Methods

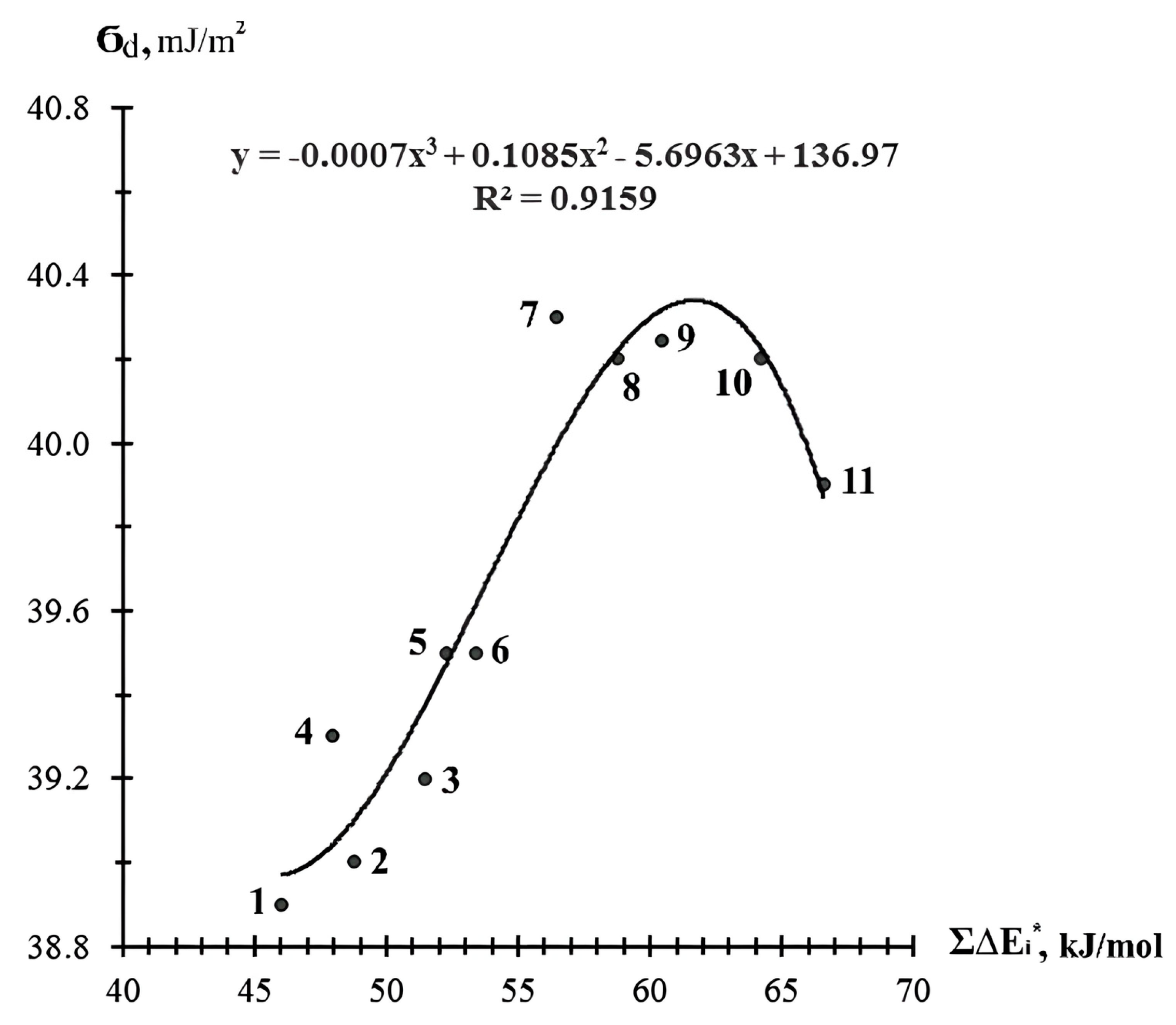

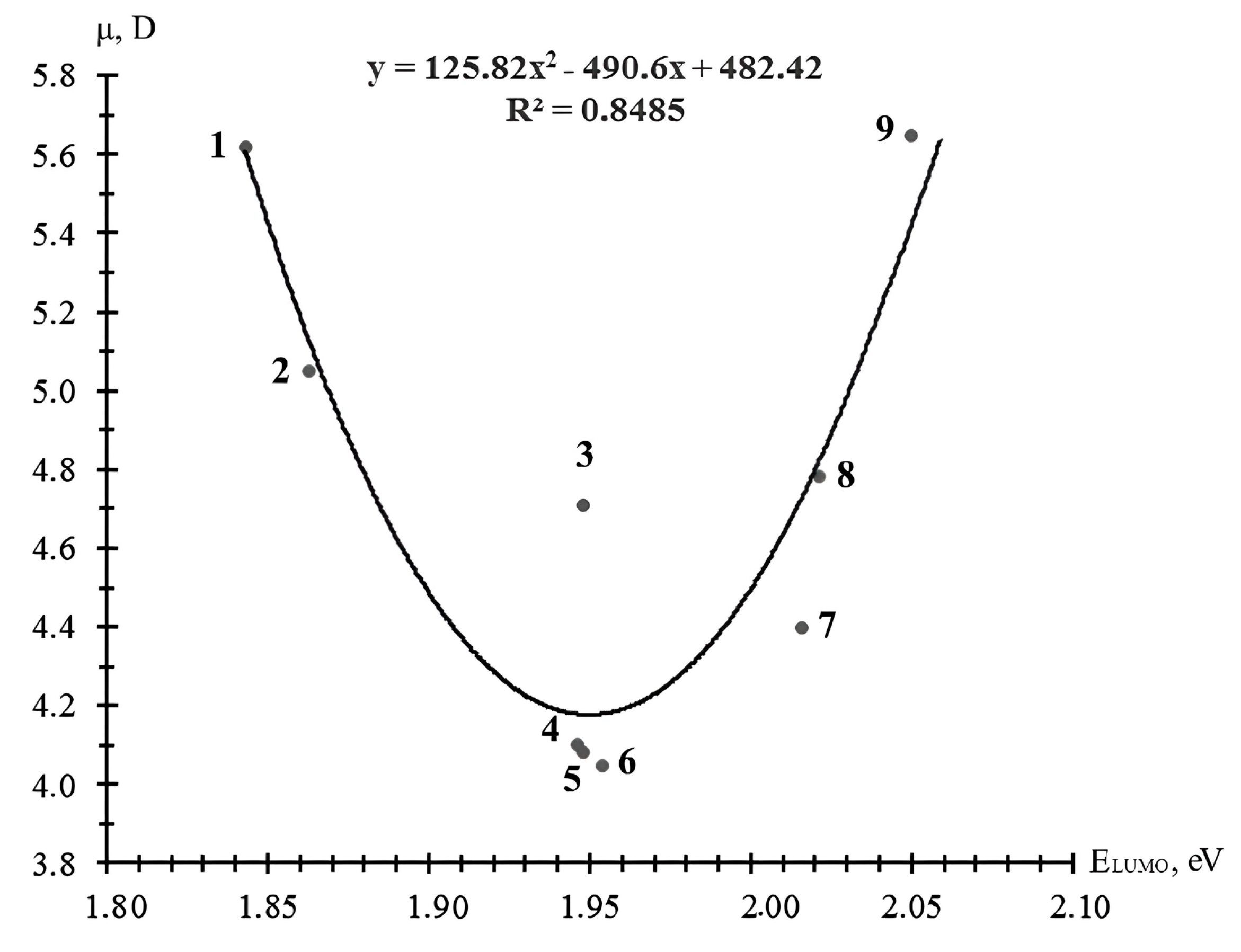

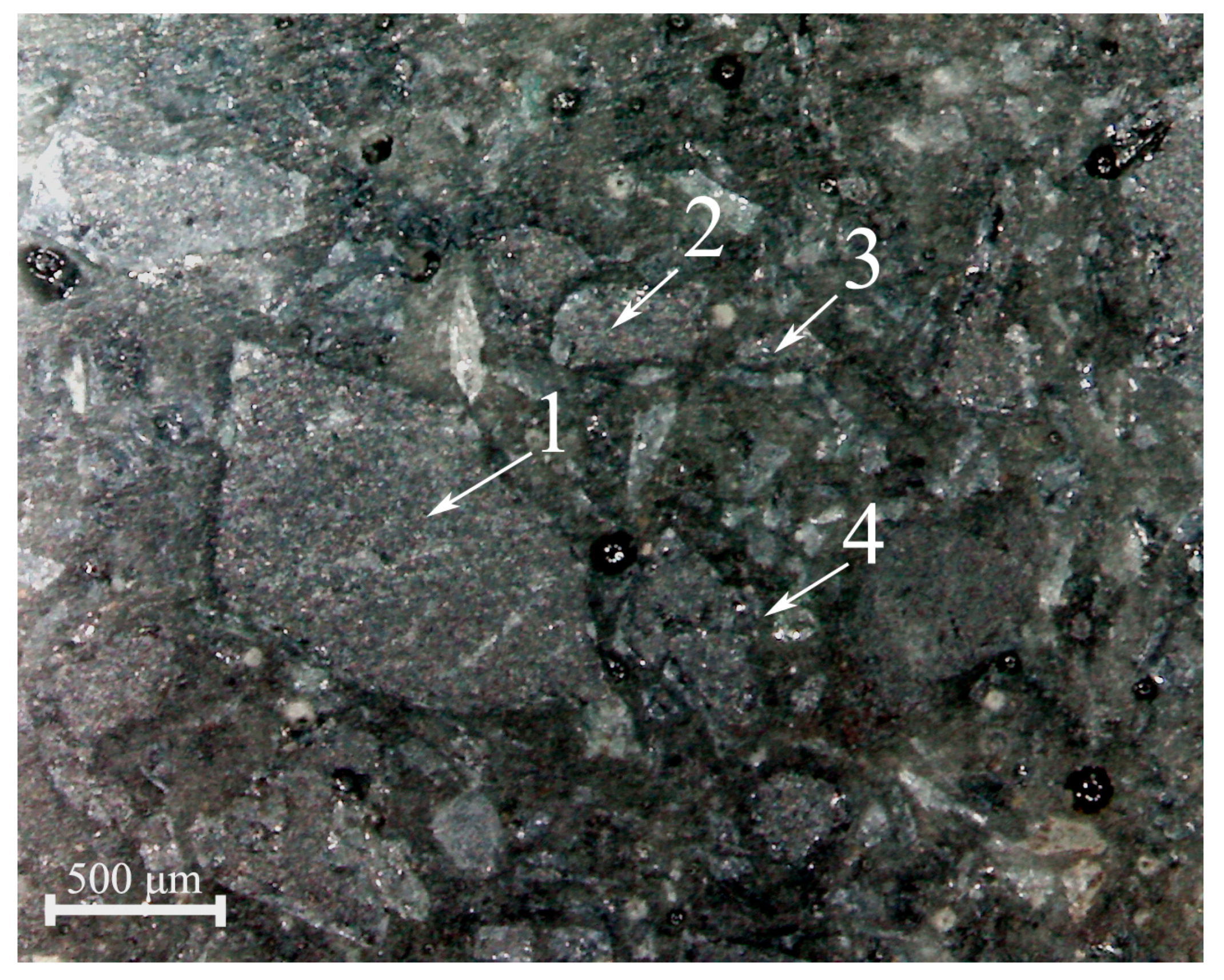

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pascault, J.R.; Williams, J.J. Epoxy Polymers: New Materials and Innovations; WileyYCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2010; 367p. [Google Scholar]

- Amal, N.; Mostafa, S.; Ismail, E.-B.; Eman, N. Improving wear resistance of epoxy/SiC composite using a modified apparatus. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2021, 29, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Li, J.; Wang, K.; Hou, X.; Yang, T.; Hu, J.; Shi, Z. Superior wear resistance of epoxy composite with highly dispersed graphene spheres. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2022, 5, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasser, D.; Navid, R.; Ali, N.; Moein, B. Effect of Different Diluents on the Main Properties of the Epoxy-Based Composite. J. Mater. Sci. Appl. 2020, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Poloz, O.Y.; Vashchenko, Y.M.; Ebich, Y.R. Povedinka modyfikovanykh rozbavnykamy znosostiykykh epoksydnykh kompozytsiy v umovakh kontaktno-dynamichnoho navantazhennya i hazoabrazyvnoho znoshuvannya [Behavior of wear-resistant epoxy compositions modified by diluents under contact-dynamic loading and gas-abrasive wear]. J. Chem. Technol. 2024, 32, 343–350. (In Ukrainian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askadskij, A.A.; Matveev, Y.I. Himicheskoe stroenie i fizicheskie svojstva polimerov. In Chemical Structure and Physical Properties of Polymers; Khimiya: Moscow, Russia, 1983; 248p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Kang, G.; Hua, L.; Feng, J. Study on Curing Kinetics and the Mechanism of Ultrasonic Curing of an Epoxy Adhesive. Polymers 2022, 14, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Xu, H.; Huang, Y. The effect of epoxy resin and curing agent groups on mechanical properties investigated by molecular dynamics. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokalj, A. Molecular modeling of organic corrosion inhibitors: Calculations, pitfalls, and conceptualization of molecule–surface bonding. Corros. Sci. 2021, 193, 109650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launay, H.; Hansen, C.M.; Almdal, K. Hansen solubility parameters for a carbon fiber/epoxy composite. Carbon 2007, 45, 2859–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, A.R.; More, A. Developments in reactive diluents: A review. Polym. Bull. 2021, 79, 5667–5708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalina, M.; Beheshty, M.H.; Salimi, A. The effect of reactive diluent on mechanical properties and microstructure of epoxy resins. Polym. Bull. 2019, 76, 3905–3927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvizi, P.; Jalilian, M.; Dearn, K.D. Epoxy composites reinforced with nanomaterials and fibres: Manufacturing, properties, and applications. Polym. Test. 2025, 146, 108761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, D.; Serra, À. Enhancement of Epoxy Thermosets with Hyperbranched and Multiarm Star Polymers: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukrainian State University of Chemical Technology; Tertyshna, O.; Zamikula, K.; Sukhyy, K.; Toropin, M.; Burmistrov, K. Kinetics of dissolution of asphalt-resin-paraffin deposits when adding dispersing agents. Voprosy Khimii i Khimicheskoi Tekhnologii 2022, 4, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhyy, K.; Belyanovskaya, E.; Nosova, A.; Sukha, I.; Sukhyy, M.; Huang, Y.; Kochergin, Y.; Hryhorenko, T. Dynamic Mechanical Properties of Epoxy Composites Modified with Polysulphide Rubber. Chem. Chem. Technol. 2022, 16, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sytar, V.I.; Kuzyayev, I.M.; Sukhyy, K.M.; Kabat, O.S. Experimental and theoretical investigation of the pore formation process in gas-filled polymeric materials. J. Chem. Technol. 2021, 29, 279–300. [Google Scholar]

- Sukhyy, K.M.; Belyanovskaya, E.A.; Nosova, A.N.; Huang, Y.; Kocherhin, Y.S.; Hryhorenko, T.I. influence Of Concentration of Thiokol, Amount of the Hardener and Filler on Properties of Epoxide-Polysulphide Composites. J. Chem. Technol. 2021, 29, 531–539. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat, O.; Sytar, V.; Derkach, O.; Sukhyy, K. Polymeric Composite Materials of Tribotechnical Purpose with a High Level of Physical, Mechanical and Thermal Properties. Chem. Chem. Technol. 2021, 15, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhyy, K.M.; Belyanovskaya, E.A.; Nosova, A.; Kochergin, Y.; Hryhorenko, T. Properties of composite materials based on epoxy resin modified with dibutyltin dibromide. Voprosy Khimii i Khimicheskoi Tekhnologii 2021, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolova, L.; Sukhyy, K. Investigation of photocatalytic activity of NiFe2O4 in the oxidation reaction of 4-nitrophenol. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2021, 720, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhyy, K.M.; Belyanovskaya, E.A.; Nosova, A.N.; Sukhyy, M.K.; Kryshen, V.P.; Huang, Y.; Kocherhin, Y.; Hryhorenko, T. Properties of epoxy-thiokol materials based on the products of the preliminary reaction of thioetherification. Vopr. Khimii i Khimicheskoi Tekhnologii 2021, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-M.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.-J. Enhancing thermo-mechanical properties of epoxy composites using fumed silica with different surface treatment. Polymers 2021, 13, 2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Wang, Q.; Pan, Z.; Lv, Z.; Chern, W.K.; Oh, J.T.; Chen, Z. Unravelling the role of filler surface wettability in long-term mechanical and dielectric properties of epoxy resin composites under hygrothermal aging. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 682, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajnerman, A.E.; Lipatov, Y.S.; Kulik, V.M.; Voloshina, L.N. Prostoj metod opredeleniya poverhnostnogo natyazheniya i kraevyh uglov smachivaniya zhidkostej [A simple method for determining the surface tension and contact angles of wetting of liquids]. Kolloidn. Zhurnal 1970, 32, 620–623. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- İsLamoğlu, F.; Erdoğan, N.; Hacifazlioğlu, E. Determination of the pKa value of some 1,2,4-triazol derivatives in forty seven different solvents using semi-empirical quantum methods (PM7, PM6, PM6-DH2, RM1, PM3, AM1, and MNDO) by MOPAC computer program. Ovidius Univ. Ann. Chem. 2023, 34, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.S.; Kubar, T.; Cui, Q.; Elstner, M. Semiempirical Quantum Mechanical Methods for Noncovalent Interactions for Chemical and Biochemical Applications. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 5301–5337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, K.I.; Gopakumar, D.; Namboori, K. Computational Chemistry and Molecular Modeling; Springer Verlag GmbH: Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; 398p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erteeb, M.A.; Ali-Shattle, E.E.; Khalil, S.M.; Berbash, H.A.; Elshawi, Z.E. Computational Studies (DFT) and PM3 Theories on Thiophene Oligomers as Corrosion Inhibitors for Iron. Am. J. Chem. 2021, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, T.A. Handbook of Computational Chemistry: A Practical Guide to Chemical Structure and Energy Calculations; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1985; 352p. [Google Scholar]

- Poloz, O.Y.; Prosyanik, O.V.; Farat, O.K.; Ebich, Y.R. Otsinka aktyvnosti aminnykh otverdzhuvachiv epoksydnykh smol [Evaluation of the activity of amine hardeners for epoxy resins]. Voprosy Khimii i Khimicheskoi Tekhnologii 2024, 2, 83–89. (In Ukrainian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klymenko, A.; Sytar, V.; Kolesnyk, I. Adhesion of poly(m-,p-phenyleneisophtalamide) coatings to metal substrates. Prog. Org. Coat. 2014, 77, 1597–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakula, V.L.; Pritykin, L.M. Physical Chemistry of Polymer Adhesion; USSR: Khimiya: Moskow, Germany, 1984; 224p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- ISO 604:2002; Plastics—Determination of Compressive Properties, Edition 3. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- ISO 178:2019; Plastics—Determination of Flexural Properties, Edition 6. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- ISO 8256:2023; Plastics—Determination of Tensile-Impact Strength, Edition 3. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- ISO 179-1:2023; Plastics—Determination of Charpy Impact Properties, Edition 3. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Hobin, T.P. Surface Tension in Relation to Cohesive Energy with Particular Reference to Hydrocarbon Polymers. J. Adhes. 1972, 3, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poloz, O.Y.; Shtompel, V.I.; Burmistrov, K.S.; Ebich, Y.R. Osoblyvosti mizhfaznoyi vzayemodiyi v epoksydnykh kompozytakh, napovnenykh sylitsiy karbidom [Features of interfacial interaction in epoxy composites silicon carbide filled]. Voprosy Khimii i Khimicheskoi Tekhnologii 2020, 1, 39–46. (In Ukrainian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatura, Y.; Okabe, S.; Iida, T. Effect of particle shape, size and interfacial adhesion of the fracture strength of silica-filled epoxy resin. Polym. Polym. Compos. 1999, 7, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical Formula (Brand) of ED | Manufacturer (Country) | Epoxy Equivalent, g | Dynamic Viscosity at 25 °C, mPa·s |

|---|---|---|---|

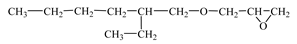

| Glycidyl ether 2-ethylhexane (RD 17)  | IPOX CHEMICALS GmbH (Laupheim, Germany) | 210–230 | 2–4 |

| Alkyl glycidyl ether C8–C10 (CHS-Epoxy RR 430)  n = 8–10 n = 8–10 | SPOLCHEMIE (Ústí nad Labem, Czech Republic) | 270–313 | 1–6 |

| Alkyl glycidyl ether C12–C14 (CHS-Epoxy RR 330; TCM AGE; RD 24)  n = 12–14 n = 12–14 | SPOLCHEMIE (Ústí nad Labem, Czech Republic); Triune Chemicals and Materials (Shoushansi Township, China); IPOX CHEMICALS GmbH (Laupheim, Germany) | 270–330 | 5–10 |

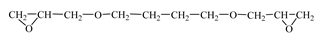

| Diglycidyl ether 1,4-butanediol (RD 3; EPODIL 750; CHS-Epoxy RR 800)  | IPOX CHEMICALS GmbH (Laupheim, Germany); Air Products (Allentown, PA, USA); SPOLCHEMIE (Ústí nad Labem, Czech Republic) | 130–145 | 12–22 |

| Diglycidyl ether dimethanolcyclohexane (RD 11)  | IPOX CHEMICALS GmbH (Laupheim, Germany) | 165–185 | 60–90 |

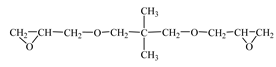

| Diglycidyl ether neopentyl glycol (RD 14)  | IPOX CHEMICALS GmbH (Laupheim, Germany) | 150–160 | 15–25 |

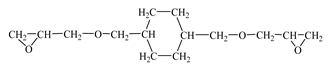

| Diglycidyl ether 1.6-hexanediol (RD 18; CHS-Epoxy RR 700)  | IPOX CHEMICALS GmbH (Laupheim, Germany); SPOLCHEMIE (Ústí nad Labem, Czech Republic) | 147–161 | 15–25 |

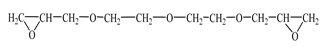

| Diglycidyl ether diethylene glycol (DEG-1)  | JSC “NIIKHIMPOLIMER” (Perm, Russia) | 140–150 | 65–75 |

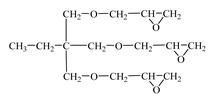

| Triglycidyl ether trimethylolpropane (CHS-Epoxy RR 690; RD 20; EPOSIR 8103)  | SPOLCHEMIE (Ústí nad Labem, Czech Republic); IPOX CHEMICALS GmbH (Laupheim, Germany); SIR industriale (Italy) | 140–150 | 120–180 |

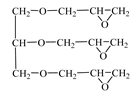

| Triglycidyl ether glycerin (CL 12)  | IPOX CHEMICALS GmbH (Laupheim, Germany) | 140–150 | 160–200 |

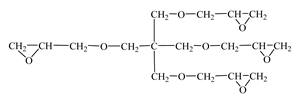

| Tetraglycidyl ether pentaerythritol (CL 16)  | IPOX CHEMICALS GmbH (Laupheim, Germany) | 156–170 | 900–1200 |

| ED | σs, mN/m | σd, mJ/m2 | Δ, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHS-Epoxy RR 690 | 38.0 | 39.6 | +4.2 |

| CHS-Epoxy RR 430 | 38.2 | 39.3 | +2.9 |

| TCM AGE | 38.3 | 40.2 | +4.9 |

| CHS-Epoxy RR 330 | 39.2 | 40.2 | +2.5 |

| DEG-1 | 43.0 | 41.3 | −4.0 |

| Brand of ED | σs, mN/m | Wk, mJ/m2 | Boron Carbide | Silicon Carbide | Normal Corundum | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ѳ, degree | Wa, mJ/m2 | χ, mJ/m2 | Ѳ, degree. | Wa, mJ/m2 | χ, mJ/m2 | Ѳ, degrees | Wa, mJ/m2 | χ, mJ/m2 | |||

| CHS–Epoxy RR 690 | 38.0 | 76.0 | 28 | 71.5 | −4.5 | 14 | 74.9 | −1.1 | 28 | 70.4 | −5.6 |

| CHS–Epoxy RR 430 | 38.2 | 76.4 | 30 | 71.3 | −5.1 | 15 | 75.1 | −1.3 | 32 | 70.6 | −5.8 |

| TCM AGE | 38.3 | 76.6 | 31 | 71.1 | −5.5 | 17 | 74.9 | −1.7 | 37 | 68.9 | −7.7 |

| CHS–Epoxy RR 330 | 39.2 | 78.4 | 35 | 71.3 | −7.1 | 26 | 74.4 | −4.0 | 41 | 68.8 | −9.6 |

| DEG-1 | 43.0 | 86.0 | 50 | 70.6 | −15.4 | 47 | 72.3 | −13.7 | 61 | 63.9 | −22.1 |

| Brand of ED | Energies of Molecular Orbitals ED, eV | EHOMO of Polyamines, eV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMDA (−9.402) | DETA (−9.289) | TETA (−9.305) | TEPA (−9.316) | AER (−9.083) | |||

| HOMO | LUMO | ǀ∆ǀ, eV | |||||

| CL 12 | −10.857 | 1.843 | 11.245 | 11.132 | 11.148 | 11.159 | 10.926 |

| CL 16 | −10.722 | 1.863 | 11.265 | 11.152 | 11.168 | 11.179 | 10.946 |

| CHS-Epoxy RR 430 | −10.986 | 1.946 | 11.348 | 11.235 | 11.251 | 11.262 | 11.029 |

| RD 3, EPODIL 750, and CHS-Epoxy RR 800 | −10.839 | 1.948 | 11.35 | 11.237 | 11.253 | 11.264 | 11.031 |

| CHS-Epoxy RR 330, TCM AGE, and RD 24 | −10.967 | 1.948 | 11.35 | 11.237 | 11.253 | 11.264 | 11.031 |

| RD 17 | −10.831 | 1.954 | 11.356 | 11.243 | 11.259 | 11.270 | 11.037 |

| RD 18 and CHS-Epoxy RR 700 | −10.782 | 1.954 | 11.356 | 11.243 | 11.259 | 11.270 | 11.037 |

| RD 11 | −10.918 | 2.016 | 11.418 | 11.305 | 11.321 | 11.332 | 11.099 |

| CHS-Epoxy RR 690, RD 20, and EPOSIR 8103 | −10.645 | 2.021 | 11.423 | 11.310 | 11.326 | 11.337 | 11.104 |

| RD 14 | −10.680 | 2.042 | 11.444 | 11.331 | 11.347 | 11.358 | 11.125 |

| Diluent | Content of Sol Fraction, % | Cross-Linking Coefficient | Impact Toughness, kJ/m2 | Bending Strength, MPa | Tensile Strength, MPa | Compressive Strength, MPa | Gas-Abrasive Wear (∆V·103, cm3) During Abrasive Attack at Angle of 15° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unfilled compositions | |||||||

| CHS-Epoxy RR 330 | 1.35 | 7.59 | 7.1 | 95 | 15.3 | 140 | 12.8 |

| CHS-Epoxy RR 430 | 0.50 | 13.14 | 8.9 | 93 | 17.9 | 145 | 8.6 |

| ERODIL 750 | 0.28 | 17.90 | 14.0 | 91 | 21.8 | 155 | 7.2 |

| CHS-Epoxy RR 690 | 0.19 | 21.94 | 16.8 | 87 | 23.1 | 163 | 6.4 |

| Filled composites (600 wt. parts of multidispersed silicon carbide of composition with a particle size (μm) of 5–7 (25%) + 125–200 (28%) + 400–500 (15%) + 1600–2000 (32%) per 100 wt. parts of epoxy resin KER828 with diluent) | |||||||

| CHS-Epoxy RR 690 | 0.21 | 20.87 | 3.3 | 61 | 15.6 | 127 | 6.9 |

| DEG-1 | 0.22 | 20.37 | 3.0 | 58 | 14.2 | 121 | 8.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kulikov, A.; Sukhyy, K.; Yeromin, O.; Fedak, M.; Prokopenko, O.; Sukha, I.; Poloz, O.; Mikats, O.; Hrebik, T.; Kulikova, O.; et al. Application of Physical and Quantum-Chemical Characteristics of Epoxy-Containing Diluents for Wear-Resistant Epoxy Compositions. Materials 2025, 18, 5643. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245643

Kulikov A, Sukhyy K, Yeromin O, Fedak M, Prokopenko O, Sukha I, Poloz O, Mikats O, Hrebik T, Kulikova O, et al. Application of Physical and Quantum-Chemical Characteristics of Epoxy-Containing Diluents for Wear-Resistant Epoxy Compositions. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5643. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245643

Chicago/Turabian StyleKulikov, Andrii, Kostyantyn Sukhyy, Oleksandr Yeromin, Marcel Fedak, Olena Prokopenko, Iryna Sukha, Oleksii Poloz, Oleh Mikats, Tomas Hrebik, Olha Kulikova, and et al. 2025. "Application of Physical and Quantum-Chemical Characteristics of Epoxy-Containing Diluents for Wear-Resistant Epoxy Compositions" Materials 18, no. 24: 5643. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245643

APA StyleKulikov, A., Sukhyy, K., Yeromin, O., Fedak, M., Prokopenko, O., Sukha, I., Poloz, O., Mikats, O., Hrebik, T., Kulikova, O., & Lopusniak, M. (2025). Application of Physical and Quantum-Chemical Characteristics of Epoxy-Containing Diluents for Wear-Resistant Epoxy Compositions. Materials, 18(24), 5643. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245643