Effects of Multi-Pass Butt-Upset Cold Welding on Mechanical Performance of Cu-Mg Alloys

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. The Mechanical Properties of Cu-Mg Alloy Before and After Cold Welding

3.2. Microstructure of the Welded Joints

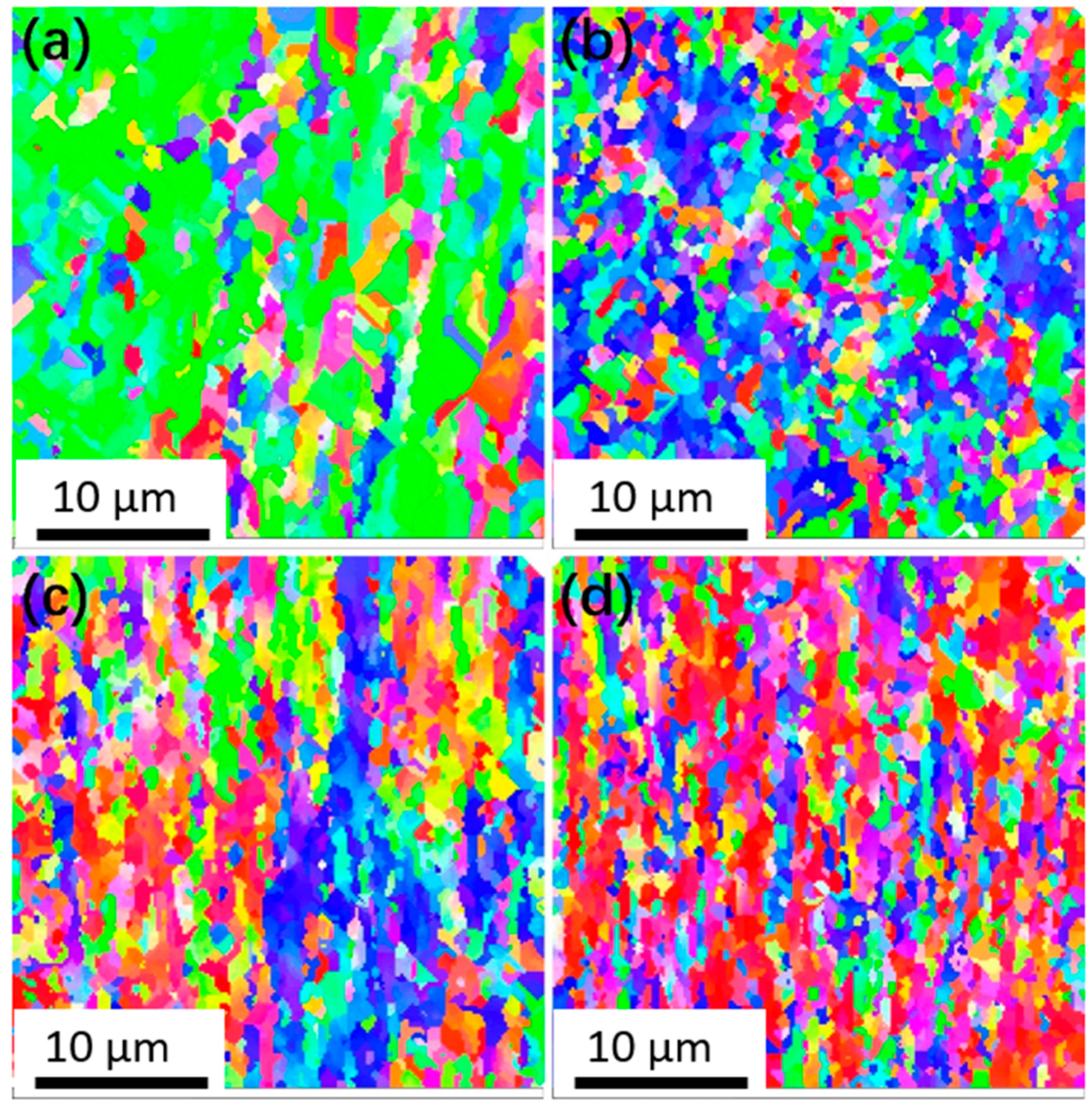

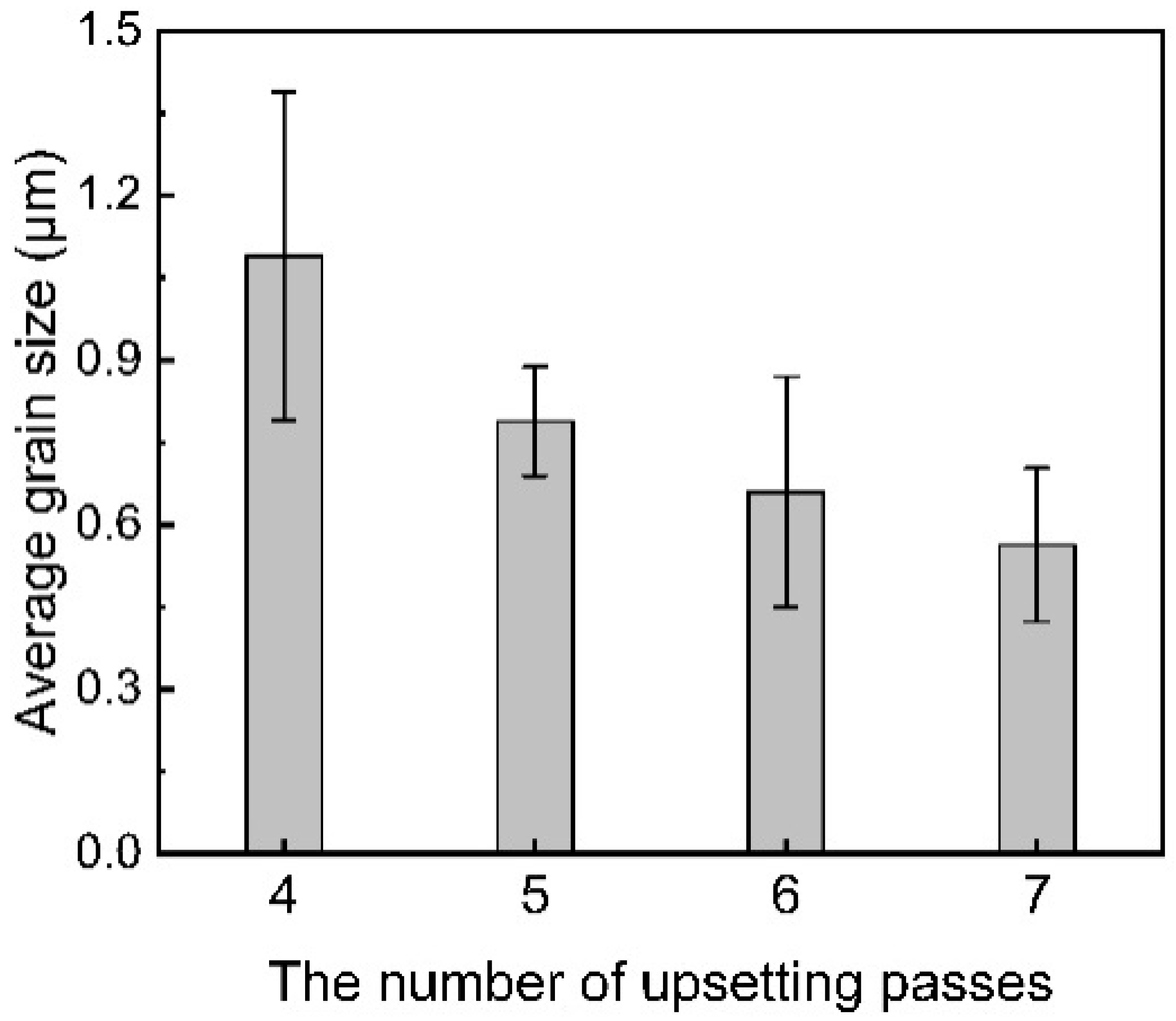

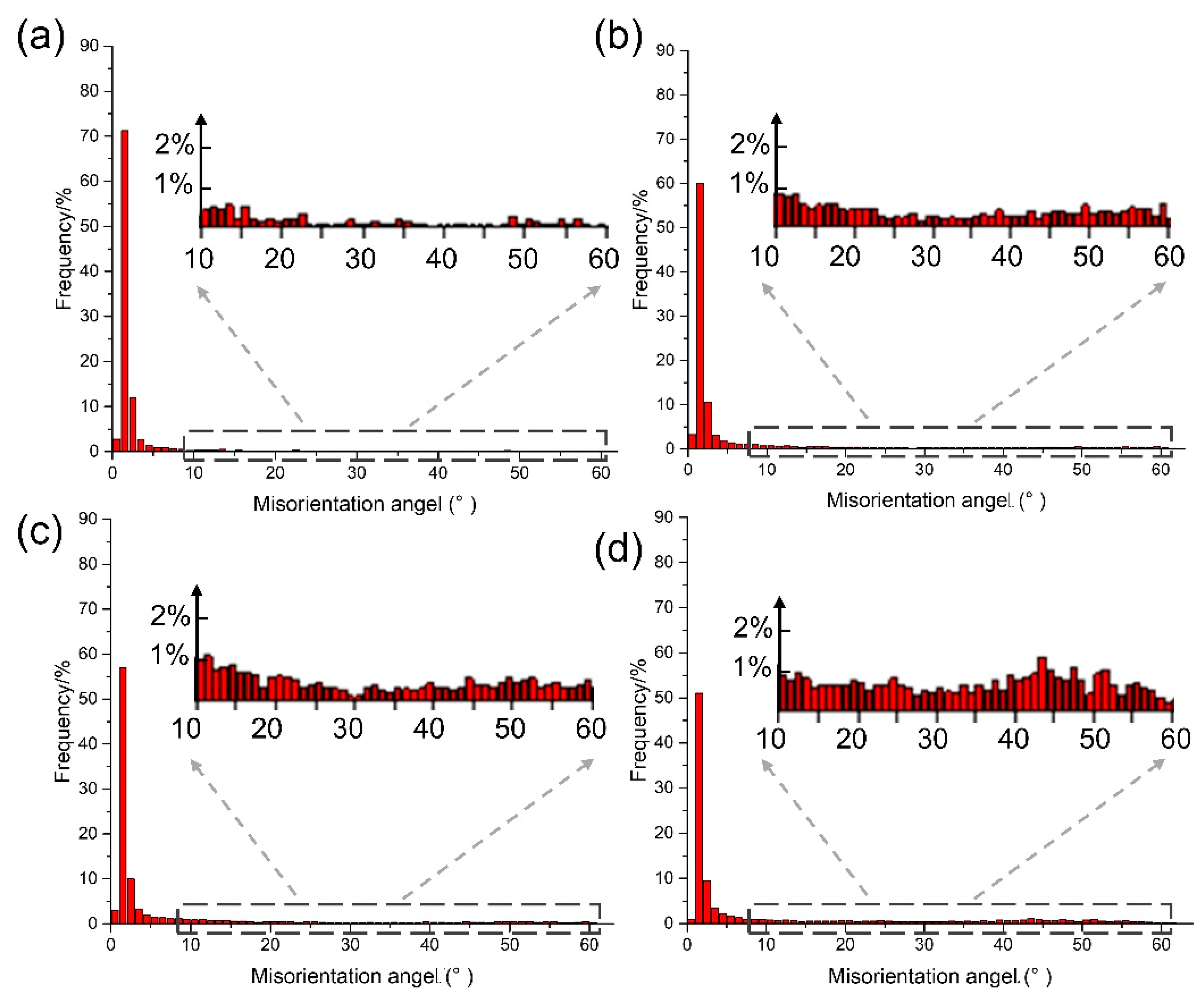

3.3. Effect of Upsetting Pass on Microstructure

4. Discussion

4.1. Deformation Inhomogeneity and the Evolution of a Gradient Microstructure

4.2. The Dynamic Bonding Mechanism in Multi-Pass Cold Welding

4.3. Microstructure and Mechanical Property

4.4. Limitations and Future Outlook

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Multi-pass upsetting cold welding of Cu-Mg alloy wire can achieve tensile stress of up to 624 MPa and 3.5% elongation at break.

- (2)

- During the cold-welding upsetting process, the Cu-Mg contact interface undergoes shear and extrusion deformation, which eventually leads to severe deformation in the central area.

- (3)

- During the multiple upsetting processes, the microscopic control theory of Cu-Mg alloy wire connection is transformed from thin film theory to plastic deformation of dislocation cross-slip.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, K.; Wang, Y.; Guo, M.; Wang, H.; Mo, Y.; Dong, X.; Lou, H. Recent Development of Advanced Precipitation-Strengthened Cu Alloys with High Strength and Conductivity: A Review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 138, 101141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Gao, G.; Wei, W.; Yang, Z. Electric Contact Material of Pantograph and Catenary. In The Electrical Contact of the Pantograph-Catenary System: Theory and Application; Wu, G., Gao, G., Wei, W., Yang, Z., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 195–220. ISBN 978-981-13-6589-8. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, Z.; Lei, Q. Microstructure and Properties of a Novel Cu-Mg-Ca Alloy with High Strength and High Electrical Conductivity. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 723, 1162–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, G.; Kim, Y.; Haochuang, L.; Koo, J.-M.; Seok, C.-S.; Lee, K.; Kwon, S.-Y. Bending Fatigue Life Evaluation of Cu-Mg Alloy Contact Wire. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2014, 15, 1331–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A.; Zhu, C.; Chen, J.; Jiang, J.; Song, D.; Ni, S.; He, Q. Grain Refinement and High-Performance of Equal-Channel Angular Pressed Cu-Mg Alloy for Electrical Contact Wire. Metals 2014, 4, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Ge, Y.; Wang, J.; Cui, J.-Z. Effect of Processing and Heat Treatment on Behavior of Cu-Cr-Zr Alloys to Railway Contact Wire. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2006, 37, 3233–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Dong, K.; Xu, Z.; Xiao, S.; Wei, W.; Chen, H.; Li, J.; Huang, Z.; Li, J.; Gao, G. Pantograph–Catenary Electrical Contact System of High-Speed Railways: Recent Progress, Challenges, and Outlooks. Railw. Eng. Sci. 2022, 30, 437–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Li, Z.; Qiu, W.; Xiao, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Jiang, Y. Microstructure and Properties of Cu–Mg-Ca Alloy Processed by Equal Channel Angular Pressing. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 788, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Ma, A.; Jiang, J.; Li, X.; Song, D.; Yang, D.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, J. Effect of ECAP Combined Cold Working on Mechanical Properties and Electrical Conductivity of Conform-Produced Cu–Mg Alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 582, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.T.; Li, L.I.; Zheng, Y.F. High Strength and High Electrical Conductivity CuMg Alloy Prepared by Cryorolling. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2019, 29, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Liu, X. Study on Influence of Contact Wire Design Parameters on Contact Characteristics of Pantograph-Catenary; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 268–273. [Google Scholar]

- Bay, N. Cold Welding. In Welding Fundamentals and Processes; ASTM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 2011; pp. 711–716. [Google Scholar]

- Periyasamy, P.S.; Sivalingam, P.; Vellingiri, V.P.; Maruthachalam, S.; Balakrishnapillai, V. A Review of Traditional and Modern Welding Techniques for Copper. Weld. Int. 2024, 38, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auwal, S.; Ramesh, S.; Yusof, F.; Manladan, S.M. A Review on Laser Beam Welding of Copper Alloys. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 96, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Yu, H.; Xia, C.; Ni, C.; Chen, C.; Wang, S.; Jia, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Yi, J. Microstructural Evolution and Bonding Mechanisms during Multi-Pass Cold Welding of High-Strength Precipitation-Hardened Alloys. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2025, 341, 118905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tusek, J.; Markelj, F.; Jez, B. Influence of Type of Welded Joint on Welding Efficiency. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2003, 8, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.; Snow, D.; Tay, C. Interfacial Conditions and Bond Strength in Cold Pressure Welding by Rolling. Met. Technol. 1978, 5, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, N.J.; Gerlitzky, C.; Altin, A.; Wohletz, S.; Krieger, W.; Tran, T.H.; Liebscher, C.H.; Scheu, C.; Dehm, G.; Groche, P. Atomic Level Bonding Mechanism in Steel/Aluminum Joints Produced by Cold Pressure Welding. Materialia 2019, 7, 100396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, N. Cold Pressure Welding—The Mechanisms Governing Bonding. J. Eng. Ind 1979, 101, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuntao, L.; Zeyu, D.; Jiang, Y. Study on Interfacial Bonding State of Ag-Cu in Cold Pressure Welding. Trans. Tianjin Univ. 2003, 9, 219–222. [Google Scholar]

- Ebbert, C.; Schmidt, H.; Rodman, D.; Nürnberger, F.; Homberg, W.; Maier, H.; Grundmeier, G. Joining with Electrochemical Support (ECUF): Cold Pressure Welding of Copper. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2014, 214, 2179–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latypov, R.A.; Bulychev, V.V.; Latypova, G.R.; Paramonov, S.S. Dislocation Model of the Formation of a Welded Joint in Cold Welding. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 38, 1351–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yücel, G.; Pinar, A.M.; Onar, V.; Özen, F.; Işitan, A. Effect of the Process Parameters on Joint Performance of Cold Pressure Butt Welded T2 Copper Joints. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 2025, 09544089251367268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, T.; Masaki, S.; Azekura, K. Bond Criterion in Cold Pressure Welding of Aluminium. Mater. Sci. Technol. 1989, 5, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, M.; Misirli, C. Properties of Cold Pressure Welded Aluminium and Copper Sheets. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 463, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQueen, H. Pressure Welding, Solid State: Role of Hot Deformation. Can. Metall. Q. 2012, 51, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, C.A.; Kumar, M.; King, W.E. Universal Features of Grain Boundary Networks in FCC Materials. J. Mater. Sci. 2005, 40, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Pang, Y.; Jia, Y.; Ni, C.; Sheng, X.; Wang, S.; Jiang, X.; Zhou, Z. Orientation Relationships between Precipitates and Matrix and Their Crystallographic Transformation in a Cu–Cr–Zr Alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 850, 143576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Seo, M.H.; Hong, S.I. Plastic Deformation Analysis of Metals during Equal Channel Angular Pressing. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2001, 113, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yan, X.; Ran, X.L. Effect of Compression/Diameter Ratio on Pure Copperbutt Cold-welded Welded Joints. J. Lanzhou Univ. Technol. 2020, 46, 28–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lilleby, A.; Grong, O.; Hemmer, H. Cold pressure welding of severely plastically deformed aluminium by divergent extrusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, A.; Yang, X.; Miura, H.; Sakai, T. Continuous Static Recrystallization in Ultrafine-Grained Copper Processed by Multi-Directional Forging. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 478, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiao, T.; Ma, E. Dynamic Processes for Nanostructure Development in Cu after Severe Cryogenic Rolling Deformation. Mater. Trans. 2003, 44, 1926–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiev, R.Z.; Islamgaliev, R.K.; Alexandrov, I.V. Bulk Nanostructured Materials from Severe Plastic Deformation. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2000, 45, 103–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, M.; Lu, L.; Shen, Y.; Suresh, S. Strength, Strain-Rate Sensitivity and Ductility of Copper with Nanoscale Twins. Acta Mater. 2006, 54, 5421–5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divinski, S.V.; Padmanabhan, K.; Wilde, G. Microstructure Evolution during Severe Plastic Deformation. Philos. Mag. 2011, 91, 4574–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeck, G. Interaction of Lomer–Cottrell Locks with Screw Dislocations. Philos. Mag. 2010, 90, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yan, X.; Ran, X. Effect of Compression on Microstructure and Properties of Single Crystal Copper Cold Pressure Welding Joints. Mater. Rep. 2020, 34, 12110–12114. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero, Z.C.; Knight, B.E.; Schuh, C.A. Six Decades of the Hall–Petch Effect–a Survey of Grain-Size Strengthening Studies on Pure Metals. Int. Mater. Rev. 2016, 61, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecking, H. Strain Hardening and Dynamic Recovery. In Dislocation Modelling of Physical Systems; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1981; pp. 197–211. [Google Scholar]

- Campilho, R.D. Advances in the Experimentation and Numerical Modeling of Material Joining Processes. Materials 2023, 17, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, K.; Cho, Y.-H.; Guo, Z.; Koo, J.-M.; Seok, C.-S. Fatigue Safety Evaluation of Newly Developed Contact Wire for Eco-Friendly High Speed Electric Railway System Considering Wear. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Technol. 2016, 3, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Condition | Tensile Strength/MPa | Yield Strength/MPa | Elongation at Break/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| As received | 649 ± 3 | 448 ± 2 | 4.0 ± 0.2 |

| Upsetting 4 passes | 582 ± 7 | 412 ± 3 | 2.8 ± 0.5 |

| Upsetting 5 passes | 612 ± 4 | 431 ± 5 | 3.1 ± 0.2 |

| Upsetting 6 passes | 624 ± 5 | 435 ± 4 | 3.2 ± 0.3 |

| Upsetting 7 passes | 613 ± 5 | 427 ± 2 | 3.5 ± 0.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, Y.; Pang, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Li, S.; Wang, Z. Effects of Multi-Pass Butt-Upset Cold Welding on Mechanical Performance of Cu-Mg Alloys. Materials 2025, 18, 5641. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245641

Yuan Y, Pang Y, Xiao Z, Li S, Wang Z. Effects of Multi-Pass Butt-Upset Cold Welding on Mechanical Performance of Cu-Mg Alloys. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5641. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245641

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Yuan, Yong Pang, Zhu Xiao, Shifang Li, and Zejun Wang. 2025. "Effects of Multi-Pass Butt-Upset Cold Welding on Mechanical Performance of Cu-Mg Alloys" Materials 18, no. 24: 5641. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245641

APA StyleYuan, Y., Pang, Y., Xiao, Z., Li, S., & Wang, Z. (2025). Effects of Multi-Pass Butt-Upset Cold Welding on Mechanical Performance of Cu-Mg Alloys. Materials, 18(24), 5641. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245641