Transforming Waste into Value: The Role of Recovered Carbon Fibre and Oil Shale Ash in Enhancing Cement-Based Structural Composites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

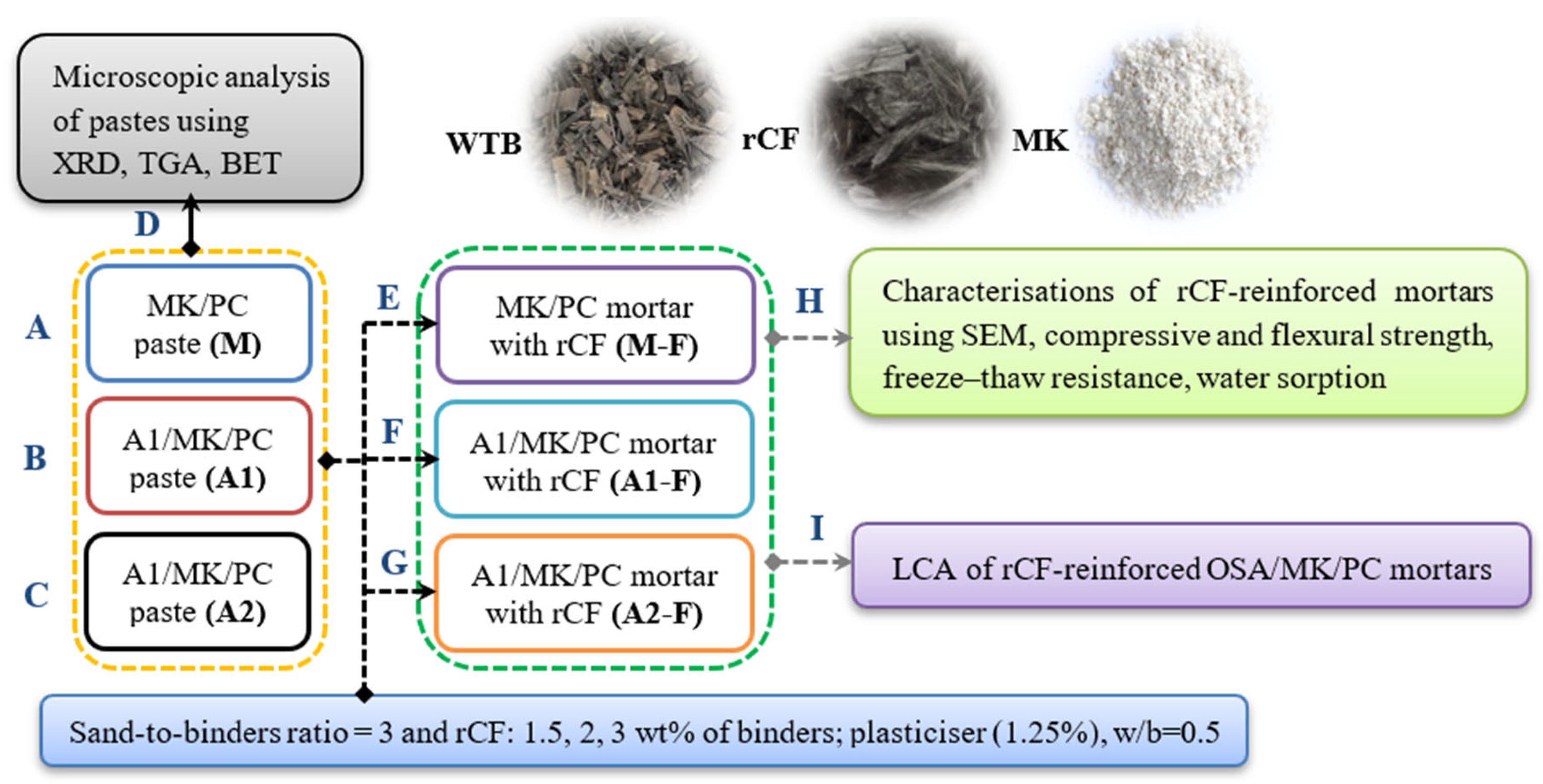

2.2. Design of the Experiments

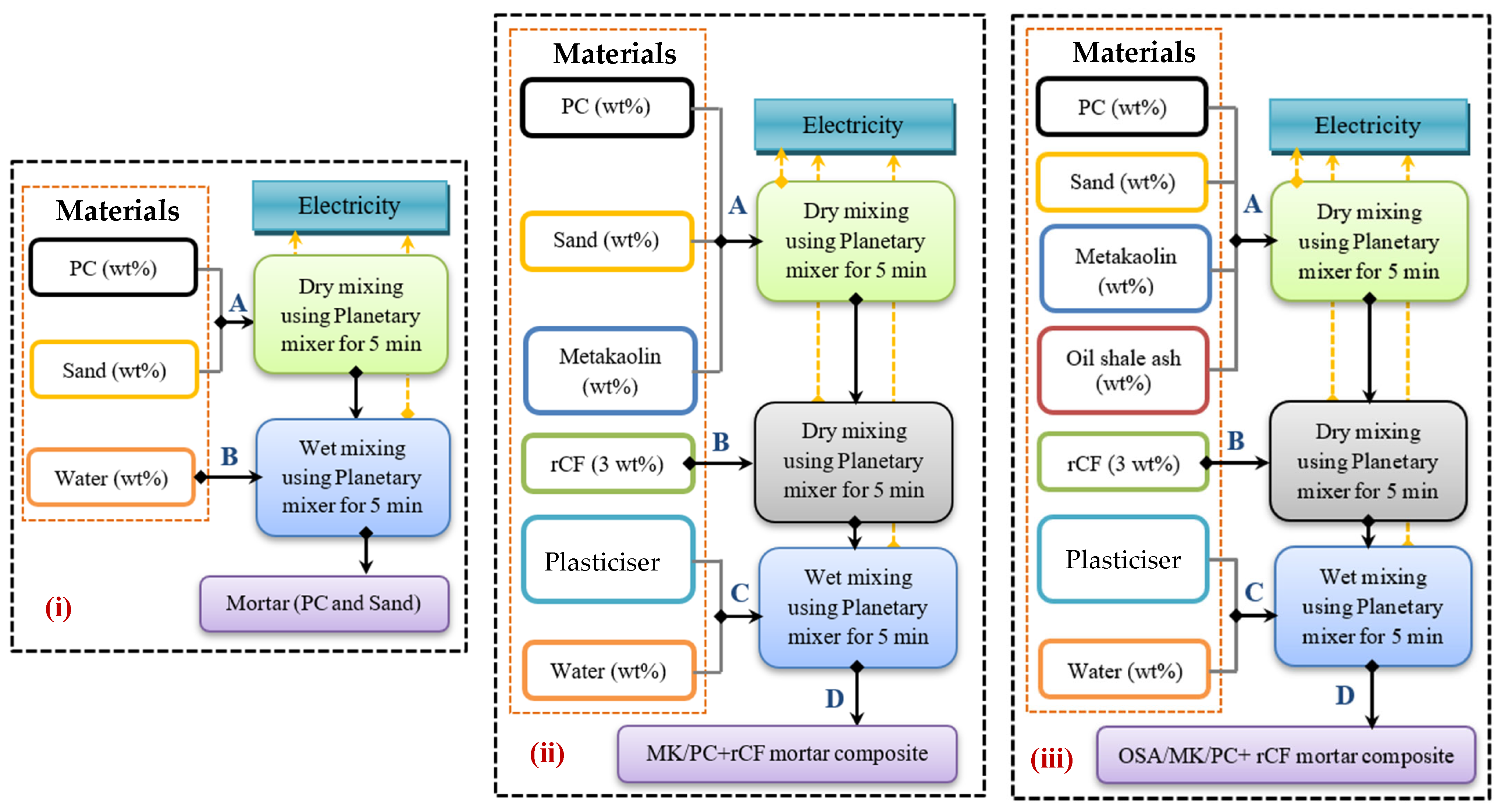

2.3. Preparation of Composites

2.4. Characterizations of the Fabricated Cement Composites

2.5. Life Cycle Assessment of rCF-Reinforced OSA/MK/PC Mortar

3. Results and Discussions

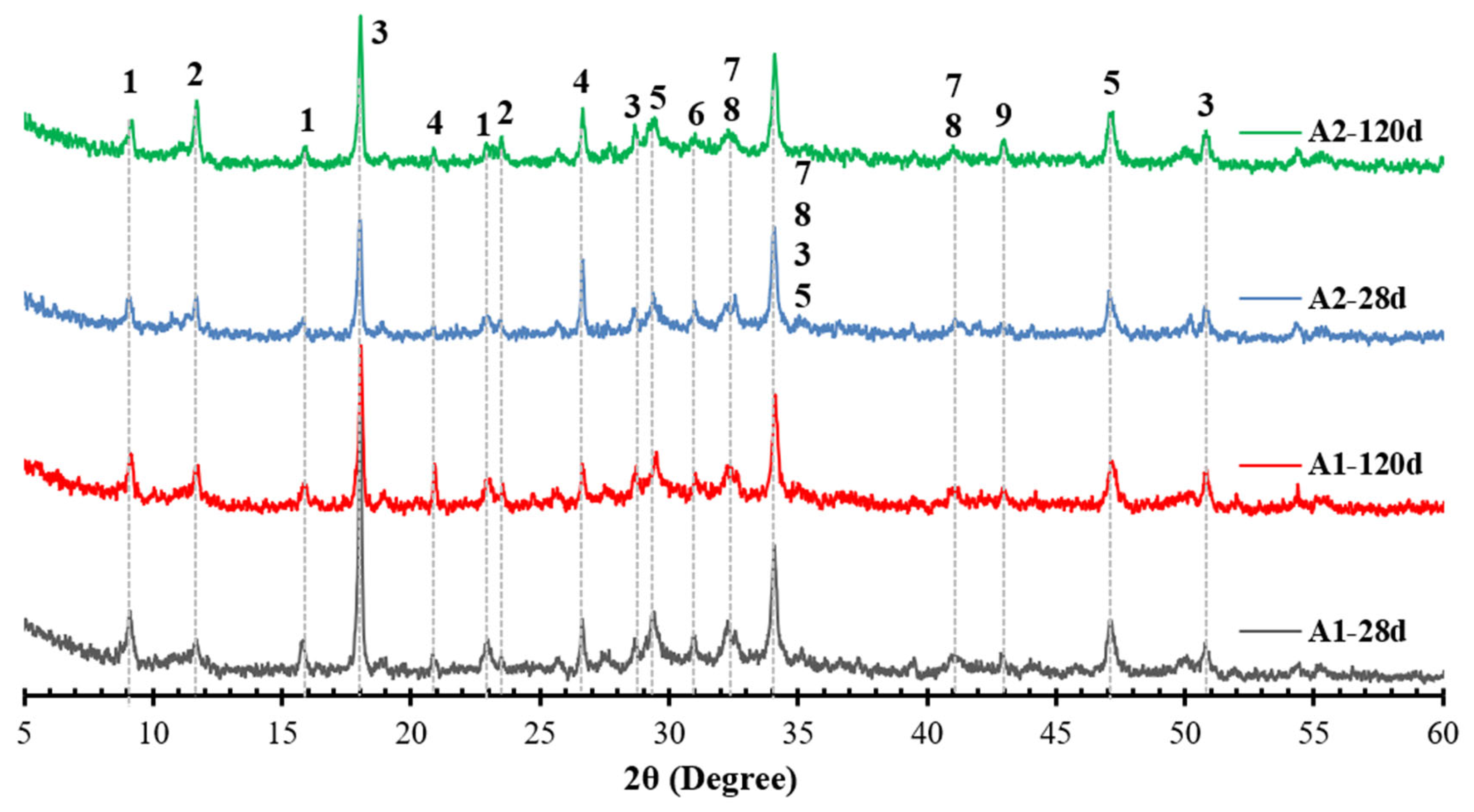

3.1. XRD Analysis of OSA/MK Cement Pastes

3.2. Thermogravimetric Analysis of OSA/MK Cement Pastes

3.3. Nitrogen Gas Physisorption Analysis of OSA/MK Cement Pastes

3.4. Morphology of rCF-Reinforced OSA/MK/PC Mortars

3.5. Compressive Properties of rCF-Reinforced OSA/MK/PC Mortars

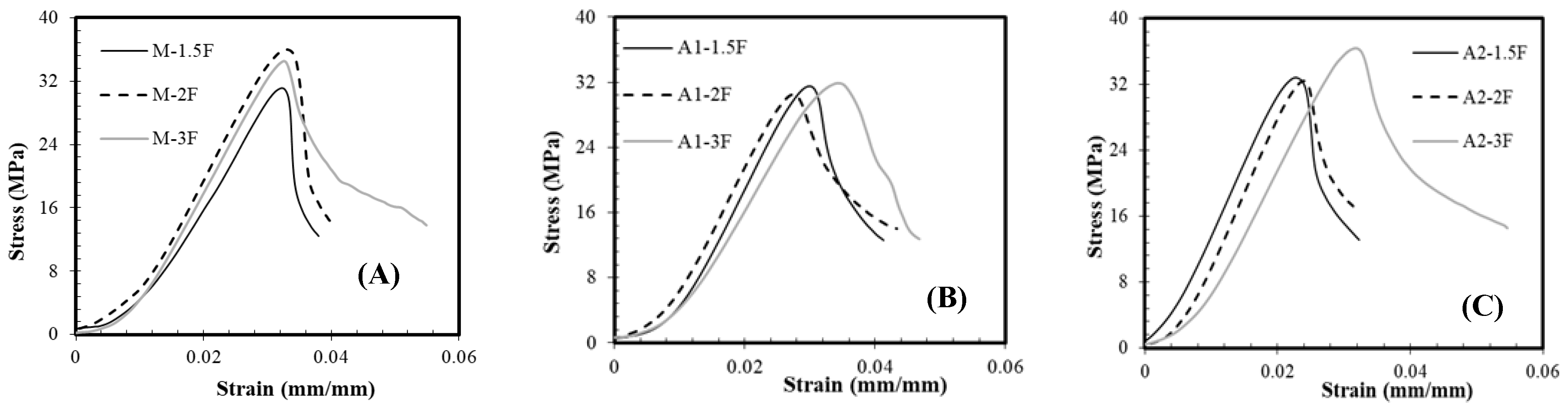

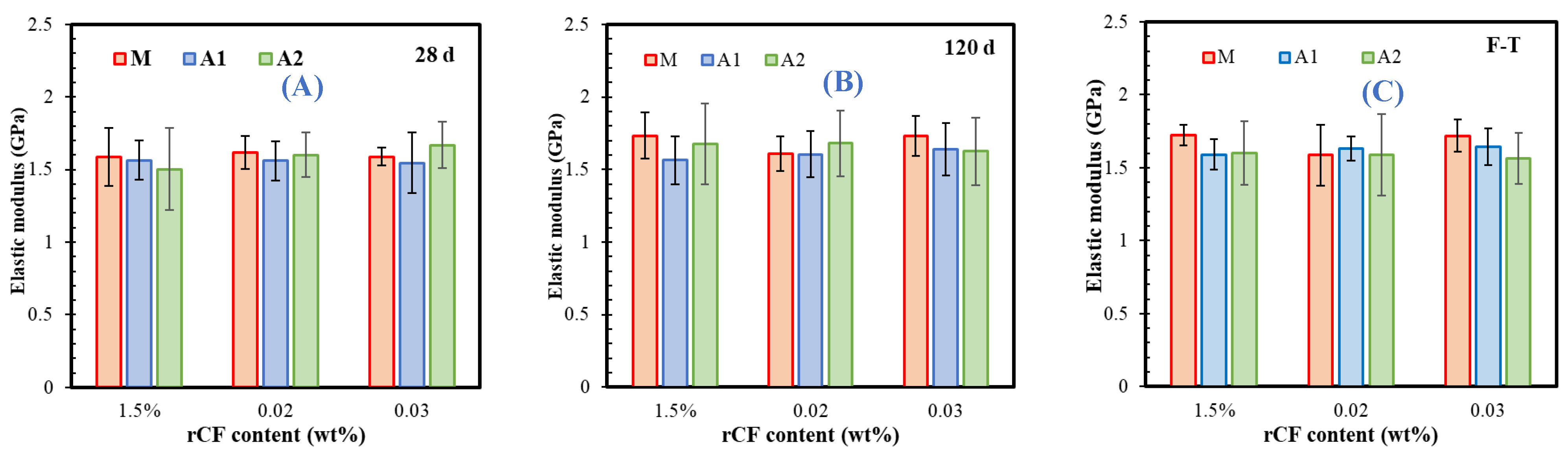

3.6. Flexural Properties of rCF-Reinforced Mortars

3.7. Freeze–Thaw Cycling

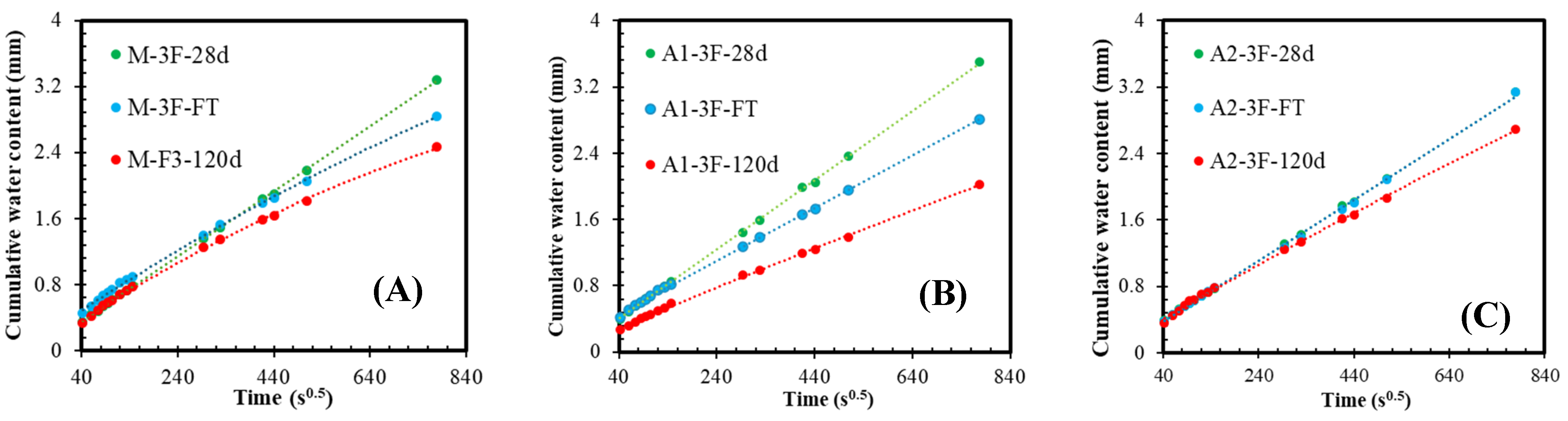

3.8. Resistance to Water Absorption and Sorptivity

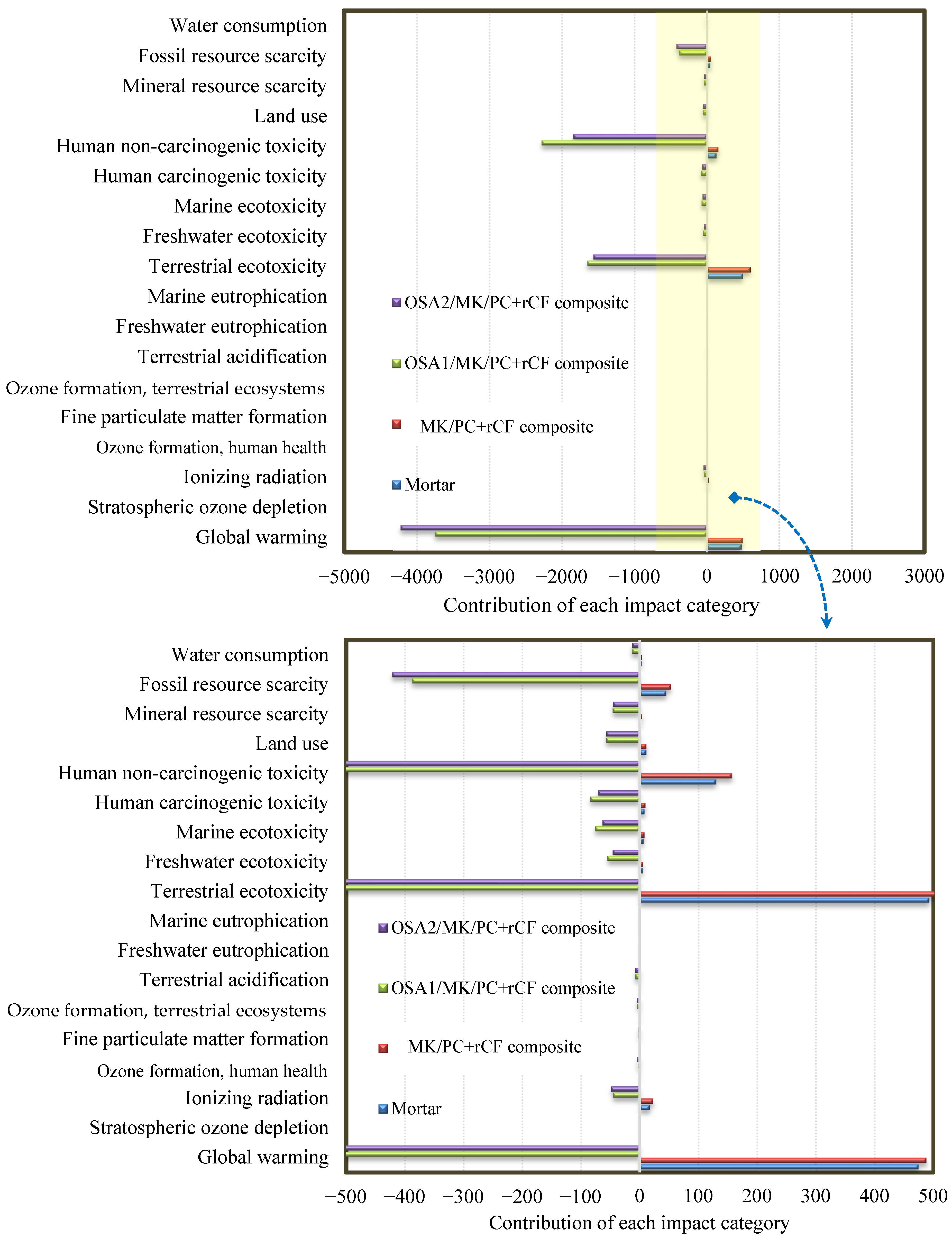

3.9. Environmental Impact Assessment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/12721/cement-industry-in-europe/#topicOverview (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1488014/market-size-of-cement-industry-europe/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC131246 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Cavalett, O.; Watanabe, M.D.B.; Voldsund, M.; Roussanaly, S.; Cherubini, F. Paving the way for sustainable decarbonization of the European cement industry. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 568–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, N.; Muthusamy, K.; Embong, R.; Kusbiantoro, A.; Hashim, M.H. Environmental impact of cement production and Solutions: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 48, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voicu, G.; Ciobanu, C.; Istrate, I.A.; Tudor, P. Emissions Control of Hydrochloric and Fluorhydric Acid in cement Factories from Romania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudhakar, C.V.; Reddy, G.U. Impacts of cement industry air pollutants on the environment and satellite data applications for air quality monitoring and management. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambataro, L.; Bre, F.; Ukrainczyk, N.; Koenders, E.A. Environmental benchmarks for the European cement industry. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 45, 429–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpokaitė-Dičkuvienė, R.; Pitak, I.; Baltušnikas, A.; Čėsnienė, J.; Kriūkienė, R.; Lukošiūtė, S.I. Functional and microstructural alterations in hydrated and freeze–thawed cement-oil shale ash composites. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashteyat, A.M.; Al Rjoub, Y.S.; Obaidat, A.T.; Kirgiz, M.; Abdel-Jaber, M.; Smadi, A. Roller Compacted Concrete with Oil Shale Ash as a Replacement of Cement: Mechanical and Durability Behavior. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2022, 17, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usta, M.C.; Yörük, C.R.; Hain, T.; Paaver, P.; Snellings, R.; Rozov, E.; Gregor, A.; Kuusik, R.; Trikkel, A.; Uibu, M. Evaluation of new applications of oil shale ashes in building materials. Minerals 2020, 10, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.V.S.; Reis, E.D.; de Azevedo, R.C.; Poggiali, F.S.J. Towards eco-friendly cement-based materials: A review on incorporating oil shale ash. Discov. Civ. Eng. 2024, 1, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thunibat, I.M.; Al-Harahsheh, A.M.; Aljbour, S.H.; Shawabkeh, A. Chemical and mechanical properties of Attarat (Jordan) Oil shale ash and its engineering viable options. Solid Fuel Chem. 2023, 57, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaloul, W.S.; Al Salaheen, M.; Malkawi, A.B.; Alzubi, K.; Al-Sabaeei, A.M.; Musarat, M.A. Utilizing of oil shale ash as a construction material: A systematic review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 299, 123844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaloul, W.S.; Al Salaheen, M.; Alzubi, K.; Musarat, M.A. Utilizing calcined and raw fly oil shale ash in the carbonation process of OPC cement-paste and mortar. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, J.; Han, L.; Li, Z. Engineering and environmental evaluation of silty clay modified by waste fly ash and oil shale ash as a road subgrade material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 196, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nov, S.; Barak, S.; Cohen, H.; Knop, Y. Treated oil shale ashes as cement and fine aggregates substitutes for the concrete industry. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 46608–46613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabab’ah, S.R.; Sharo, A.A.; Alqudah, M.M.; Ashteyat, A.M.; Saleh, H.O. Effect of using Oil Shale Ash on geotechnical properties of cement-stabilized expansive soil for pavement applications. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, R.; Klaus, J. Influence of metakaolin on the properties of mortar and concrete: A review. Appl. Clay Sci. 2009, 43, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Pei, L.; Fu, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, T.; Liang, H.; Yang, H. Investigating the mechanical properties and durability of Metakaolin-Incorporated mortar by different curing methods. Materials 2022, 15, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Tian, Z.; Ye, H.; He, Z.; Tang, S. The role of metakaolin in pore structure evolution of Portland cement pastes revealed by an impedance approach. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 119, 103999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homayoonmehr, R.; Ramezanianpour, A.A.; Mirdarsoltany, M. Influence of metakaolin on fresh properties, mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of concrete and its sustainability issues: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 103011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, Y.; Wu, P.; Guo, Z.; Qiu, J.; Xing, J.; Xiaowei, G. Modification of high-volume fly ash cement with metakaolin for its utilization in cemented paste backfill: The effects of metakaolin content and particle size. Powder Technol. 2021, 393, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujjavanich, S.; Suwanvitaya, P.; Chaysuwan, D.; Heness, G. Synergistic effect of metakaolin and fly ash on properties of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 155, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabanshikov, Y.; Pham, T.H.; Akimov, S. Effect of metakaolin and MC adhesive additives on the mechanical properties of concrete. In Sustainable Energy Systems: Innovative Perspectives, Proceedings of the SES 2020, Saint-Petersburg, Russia, 29–30 October 2020; Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, M.; Dehestani, M.; Hosseinzadeh, A. Exploring elastic properties of fly ash recycled aggregate concrete: Insights from multiscale modeling and machine learning. Structures 2023, 59, 105720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, H.; Schnell, J. Short Fibre Reinforced Cementitious Composites and Ceramics. In Advanced Structured Materials; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakravan, H.R.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Synthetic fibers for cementitious composites: A critical and in-depth review of recent advances. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 207, 491–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Bao, Y.; Meng, W. Review of using glass in high-performance fiber-reinforced cementitious composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 120, 104032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carloni, C.; Bournas, D.A.; Carozzi, F.G.; D’Antino, T.; Fava, G.; Focacci, F.; Giacomin, G.; Mantegazza, G.; Pellegrino, C.; Perinelli, C.; et al. Fiber Reinforced Composites with Cementitious (Inorganic) Matrix. In Design Procedures for the Use of Composites in Strengthening of Reinforced Concrete Structures: State-of-the-Art Report of the RILEM Technical Committee 234-DUC; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 349–392. [Google Scholar]

- Abedi, M.; Hassanshahi, O.; Rashiddel, A.; Ashtari, H.; Meddah, M.S.; Dias, D.; Arjomand, M.; Choong, K.K. A sustainable cementitious composite reinforced with natural fibers: An experimental and numerical study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 378, 131093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampragkou, P.; Kamperidou, V.; Stefanidou, M. Evaluation of Hydrothermally Treated Wood Fibre Performance in Cement Mortars. Fibers 2024, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aduwenye, P.; Chong, B.W.; Gujar, P.; Shi, X. Mechanical properties and durability of carbon fiber reinforced cementitious composites: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 452, 138822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Huang, Y.; Li, C.; Tang, Z.; Quan, W.; Xiong, X.; He, J.; Wu, W. Damage prediction and long-term cost performance analysis of glass fiber recycled concrete under freeze-thaw cycles. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, A.; Mosaberpanah, M.A.; Salim, M.U.; Amran, M.; Fediuk, R.; Ozbakkaloglu, T.; Rashid, M.F. Utilization of recycled carbon fiber reinforced polymer in cementitious composites: A critical review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 53, 104583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, N.; Raj, R.; Singh, P. Feasibility of recycled Carbon Fiber-Reinforced polymer fibers in cementitious composites: An experimental investigation. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 49, 13577–13591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Luo, D.; Shi, X. Effect of chemically modified recycled carbon fiber composite on the mechanical properties of cementitious mortar. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 173, 106853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, J.-P.; Lee, S.-J.; Kim, Y.-J.; Jang, C.-I.; Lee, S.-W. The effect of exposure to alkaline solution and water on the strength–porosity relationship of GFRP rebar. Compos. Part B Eng. 2008, 39, 764–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, D.; Gu, T.; Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Zhao, F.; Len, S.; Dou, J.; Qian, X.; Wang, J. Degradation behavior and ageing mechanism of E-glass fiber reinforced epoxy resin composite pipes under accelerated thermal ageing conditions. Compos. Part B Eng. 2023, 270, 111131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Xu, X.; Lu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lo, S. Pyrolysis study of waste phenolic fibre-reinforced plastic by thermogravimetry/Fourier transform infrared/mass spectrometry analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 165, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Xu, L.; Han, Z.; Xiao, S.; Sun, Y.; Nan, Z.; Shu, J.; Li, L.; Shen, Z. Study on recycling carbon fibers from carbon fiber reinforced polymer waste by microwave molten salt pyrolysis. Fuel 2024, 377, 132819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, S.; Eimontas, J.; Striūgas, N.; Abdelnaby, M.A. Pyrolysis kinetic behaviour and thermodynamic analysis of waste wind turbine blades (carbon fibres/unsaturated polyester resin). Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2023, 45, 10505–10522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Barlow, C.Y. Wind turbine blade waste in 2050. Waste Manag. 2017, 62, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, S.; Eimontas, J.; Zakarauskas, K.; Striūgas, N. Recovery of styrene-rich oil and glass fibres from fibres-reinforced unsaturated polyester resin end-of-life wind turbine blades using pyrolysis technology. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2023, 173, 106100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-H.; Jiang, H.; Chen, W.-W.; Wu, Y.-C.; Xu, M.-X.; Di, J.-Y.; Li, W.; Lu, Q. Selective production of phenol from the end-of-life wind turbine blade through catalytic pyrolysis. Fuel 2024, 378, 132877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, S.; Eimontas, J.; Striūgas, N.; Abdelnaby, M.A. Synthesis of value-added aromatic chemicals from catalytic pyrolysis of waste wind turbine blades and their kinetic analysis using artificial neural network. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2023, 177, 106330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, S.; Eimontas, J.; Stasiulaitiene, I.; Zakarauskas, K.; Striūgas, N. Recovery of energy and carbon fibre from wind turbine blades waste (carbon fibre/unsaturated polyester resin) using pyrolysis process and its life-cycle assessment. Environ. Res. 2023, 245, 118016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, S.; Kalpokaitė-Dičkuvienė, R. Sustainable mortar reinforced with recycled glass fiber derived from pyrolysis of wind turbine blade waste. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 31, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, S.; Eimontas, J.; Zakarauskas, K.; Stasiulaitiene, I.; Striūgas, N.; Tuckute, S. Catalytic pyrolysis of wind turbine blades waste for plasticizers recovery and its life cycle assessment. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 395, 127690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 197-1:2000/A1:2004; Cement—Part 1: Composition, Specifications and Conformity Criteria for Common Cements. CEN: Brussel, Belgium, 2000.

- Kalpokaitė-Dičkuvienė, R.; Baltušnikas, A.; Levinskas, R.; Čėsnienė, J. Incinerator residual ash—Metakaolin blended cements: Effect on cement hydration and properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 206, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 934-3:2009; Admixtures for Concrete, Mortar and Grout—Part 3: Admixtures for Masonry Mortar—Definitions, requirements, Conformity and Marking and Labelling. CEN: Brussel, Belgium, 2009.

- Leben, K.; Mõtlep, R.; Paaver, P.; Konist, A.; Pihu, T.; Paiste, P.; Heinmaa, I.; Nurk, G.; Anthony, E.J.; Kirsimäe, K. Long-term mineral transformation of Ca-rich oil shale ash waste. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 658, 1404–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Liu, Y. Reinforcement Effect of Recycled CFRP on Cement-Based Composites: With a Comparison to Commercial Carbon Fiber Powder. Struct. Durab. Health Monit. 2024, 18, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Qiang, S.; Lu, H.; Li, J. Effect of carbon fibers and graphite particles on mechanical properties and electrical conductivity of cement composite. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 94, 110036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhandapani, Y.; Joseph, S.; Bishnoi, S.; Kunther, W.; Kanavaris, F.; Kim, T.; Irassar, E.; Castel, A.; Zunino, F.; Machner, A.; et al. Durability performance of binary and ternary blended cementitious systems with calcined clay: A RILEM TC 282-CCL, review. Mater. Struct. 2022, 55, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, S.; Kalpokaitė-Dičkuvienė, R.; Baltušnikas, A.; Pitak, I.; Lukošiūtė, S.I. A new strategy for functionalization of char derived from pyrolysis of textile waste and its application as hybrid fillers (CNTs/char and graphene/char) in cement industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 128058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Li, C.; Hu, Z.; Shen, X.; Chen, B. Impact of silica fume on the long-term stability of cement-based materials with low water-to-binder ratio under different curing conditions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 450, 138604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 196-1:2005; Methods of Testing Cement—Part 1: Determination of Strength. CEN: Brussel, Belgium, 2005.

- EN 1015-18:2002; Methods of Test for Mortar for Masonry—Part 18: Determination of Water Absorption Coefficient Due to Capillary Action of Hardened Mortar. CEN: Brussel, Belgium, 2002.

- LST L 1413.11:2005; Mortar. Test methods. Determination of Frost Resistance. LSD: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2005.

- Santos, T.; Almeida, J.; Silvestre, J.; Faria, P. Life cycle assessment of mortars: A review on technical potential and drawbacks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 288, 123069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, A.; Liew, K.M. Multicriteria performance evaluation of fiber-reinforced cement composites: An environmental perspective. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 218, 108937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Basteris, J.; Rivero, J.C.S.; Menéndez, B. Life cycle assessment of restoration mortars and binders. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 326, 126863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrela, F.; Rosales, M.; Alonso, M.L.; Ordóñez, J.; Cuenca-Moyano, G.M. Life-Cycle Assessment and Environmental Costs of Cement-Based Materials Manufactured with Mixed Recycled Aggregate and Biomass Ash. Materials 2024, 17, 4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, J.; Faria, P.; Ribeiro, A.B.; Silva, A.S. Life cycle assessment of mortars produced partially replacing cement by treated mining residues. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onuaguluchi, O.; Mohamed, B.; Adwan, A.; Li, L.; Banthia, N. Sludge-derived biochar as an additive in cement mortar: Mechanical strength and life cycle assessment (LCA). Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 425, 135959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balea, A.; Fuente, E.; Monte, M.C.; Blanco, A.; Negro, C. Recycled Fibers for Sustainable Hybrid Fiber Cement Based Material: A Review. Materials 2021, 14, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zajac, M.; Rossberg, A.; Le Saout, G.; Lothenbach, B. Influence of limestone and anhydrite on the hydration of Portland cements. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2014, 46, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu-Amankwah, S.; Zajac, M.; Stabler, C.; Lothenbach, B.; Black, L. Influence of limestone on the hydration of ternary slag cements. Cem. Concr. Res. 2017, 100, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu-Amankwah, S.; Black, L.; Skocek, J.; Ben Haha, M.; Zajac, M. Effect of sulfate additions on hydration and performance of ternary slag-limestone composite cements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 164, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damidot, D.; Lothenbach, B.; Herfort, D.; Glasser, F. Thermodynamics and cement science. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011, 41, 679–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, M.; Rossen, J.; Martirena, F.; Scrivener, K. Cement substitution by a combination of metakaolin and limestone. Cem. Concr. Res. 2012, 42, 1579–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zunino, F.; Scrivener, K. The reaction between metakaolin and limestone and its effect in porosity refinement and mechanical properties. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 140, 106307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeki, N.; Kurihara, R.; Ohkubo, T.; Teramoto, A.; Suda, Y.; Kitagaki, R.; Maruyama, I. Semi-dry natural carbonation at different relative humidities: Degree of carbonation and reaction kinetics of calcium hydrates in cement paste. Cem. Concr. Res. 2024, 189, 107777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargis, C.W.; Chen, I.; Wang, Y.; Maraghechi, H.; Gilliam, R.J.; Monteiro, P.J. Microstructure development of calcium carbonate cement through polymorphic transformations. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 153, 105715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlumberger, C.; Thommes, M. Characterization of Hierarchically Ordered Porous Materials by Physisorption and Mercury Porosimetry—A Tutorial Review. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 8, 2002181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boris, R.; Antonovič, V.; Kerienė, J.; Stonys, R. The effect of carbon fiber additive on early hydration of calcium aluminate cement. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2016, 125, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, A.; Kodur, V.; Liew, K. Microstructural changes and mechanical performance of cement composites reinforced with recycled carbon fibers. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 121, 104069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiuddin, M.; Abdel-Sayed, G.; Hearn, N. Absorption and strength properties of short carbon fiber reinforced mortar composite. Buildings 2021, 11, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, G.-H.; Park, J.-G.; Song, K.-C.; Jun, H.-M. Mechanical Properties of SiO2-Coated Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Mortar Composites with Different Fiber Lengths and Fiber Volume Fractions. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 8881273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Shi, M.; Ban, T.; Hou, B.; Zhang, W.; Kong, X. Using graphene oxide to enhance the bonding properties between carbon fibers and cement matrix to improve the mechanical properties of cement-based composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 453, 138992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paktiawal, A.; Alam, M. Experimental evaluation of sorptivity for high strength concrete reinforced with zirconia rich glass fiber and basalt fiber. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 49, 1132–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaei, D.; Hassanli, R.; Ma, X.; Duan, J.; Zhuge, Y. Sorptivity and mechanical properties of fiber-reinforced concrete made with seawater and dredged sea-sand. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 270, 121436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | CaO | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | TiO2 | P2O5 | K2O | MgO | Na2O | SO3 | MnO | LOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC | 63.72 | 13.82 | 3.85 | 1.75 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.33 | 1.01 | 0.23 | 2.02 | 0.12 | 2.66 |

| MK | 0.16 | 47.80 | 40.1 | 0.39 | 1.06 | 0.51 | 0.49 | - | - | - | - | 0.51 |

| OSA1 | 31.95 | 23.51 | 7.54 | 4.46 | 0.52 | 0.18 | 4.23 | 4.60 | 0.42 | 9.50 | 0.06 | 6.42 |

| OSA2 | 38.77 | 22.07 | 7.90 | 3.93 | 0.53 | 0.15 | 3.84 | 3.53 | 0.16 | 4.52 | 0.05 | 9.75 |

| Components | Control (M) Groups | A1 Groups | A2 Groups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M-1.5F | M-2F | M-3F | A1-1.5F | A1-2F | A1-3F | A2-1.5F | A2-2F | A2-3F | |

| PC (wt.%) | 94 | 94 | 94 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 74 |

| MK (wt.%) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| A1 (wt.%) | - | - | - | 20 | 20 | 20 | - | - | - |

| A2 (wt.%) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| rCFs (wt.%) | 1.5 | 2 | 3 | 1.5 | 2 | 3 | 1.5 | 2 | 3 |

| Plasticiser (wt.%) of binder content | 1.25 | ||||||||

| Binder-to-sand ratio | 1:3 | ||||||||

| Input Materials | Estimated Value per FU | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortar | MK/PC + rCF Mortar | OSA/MK/PC + rCF Mortar (A1-3F and A2-3F) | |

| Portland cement (PC) | 496.2 | 473.11 | 297.32 |

| Sand | 1488.6 | 1503.36 | 1200.67 |

| Metakaolin (MK) | ---- | 28.57 | 22.82 |

| Oil shale ash (OSA) | ---- | ---- | 80.54 |

| Recycled short carbon fibre (rCFs) | ---- | 9.05 | 9.05 |

| Plasticiser | ---- | 8.98 | 10.08 |

| Water | 248.1 | 255.46 | 209.40 |

| Total mass | 2233 | 2279 | 1830 |

| Electricity for dry mixing (kwh/FU) [64] | 8.93 | 8.93 | 8.93 |

| Electricity for wet mixing (kwh/FU) [64] | 8.93 | 8.93 | 8.93 |

| Sample | A1 Paste | A2 Paste | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydration time | 28 days | 120 days | 28 days | 120 days |

| Bound water (%) | 20.58 | 21.89 | 24.66 | 25.85 |

| Portlandite (%) | 12.54 | 10.67 | 12.30 | 15.94 |

| Carbonate (%) | 11.05 | 12.51 | 14.53 | 20.43 |

| Impact Category | Unit | Mortar | MK/PC + rCF Composite | OSA1/MK/PC + rCF Composite | OSA2/MK/PC + rCF Composite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global warming | kg CO2 eq | 474.8 | 488.6 | −3748.7 | −4224.7 |

| Stratospheric ozone depletion | kg CFC11 eq | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Ionising radiation | kBq Co-60 eq | 17.3 | 23.0 | −45.5 | −48.9 |

| Ozone formation, human health | kg NOx eq | 0.8 | 0.9 | −3.7 | −3.9 |

| Fine particulate matter formation | kg PM2.5 eq | 0.3 | 0.3 | −2.5 | −2.5 |

| Ozone formation, terrestrial ecosystems | kg NOx eq | 0.9 | 0.9 | −4.0 | −4.3 |

| Terrestrial acidification | kg SO2 eq | 0.8 | 0.8 | −7.5 | −7.6 |

| Freshwater eutrophication | kg P eq | 0.1 | 0.1 | −0.2 | −0.2 |

| Marine eutrophication | kg N eq | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Terrestrial ecotoxicity | kg 1,4-DCB | 493.5 | 600.6 | −1651.1 | −1567.3 |

| Freshwater ecotoxicity | kg 1,4-DCB | 4.6 | 5.8 | −54.9 | −45.9 |

| Marine ecotoxicity | kg 1,4-DCB | 6.2 | 7.8 | −75.8 | −63.5 |

| Human carcinogenic toxicity | kg 1,4-DCB | 8.3 | 9.4 | −84.0 | −70.6 |

| Human non-carcinogenic toxicity | kg 1,4-DCB | 129.9 | 157.4 | −2279.6 | −1844.4 |

| Land use | m2a crop eq | 10.9 | 11.4 | −57.3 | −57.0 |

| Mineral resource scarcity | kg Cu eq | 2.5 | 4.3 | −45.8 | −45.3 |

| Fossil resource scarcity | kg oil eq | 45.0 | 52.9 | −387.4 | −421.7 |

| Water consumption | m3 | 3.1 | 3.5 | −13.5 | −13.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kalpokaitė-Dičkuvienė, R.; Stasiulaitiene, I.; Baltušnikas, A.; Yousef, S. Transforming Waste into Value: The Role of Recovered Carbon Fibre and Oil Shale Ash in Enhancing Cement-Based Structural Composites. Materials 2025, 18, 5636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245636

Kalpokaitė-Dičkuvienė R, Stasiulaitiene I, Baltušnikas A, Yousef S. Transforming Waste into Value: The Role of Recovered Carbon Fibre and Oil Shale Ash in Enhancing Cement-Based Structural Composites. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245636

Chicago/Turabian StyleKalpokaitė-Dičkuvienė, Regina, Inga Stasiulaitiene, Arūnas Baltušnikas, and Samy Yousef. 2025. "Transforming Waste into Value: The Role of Recovered Carbon Fibre and Oil Shale Ash in Enhancing Cement-Based Structural Composites" Materials 18, no. 24: 5636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245636

APA StyleKalpokaitė-Dičkuvienė, R., Stasiulaitiene, I., Baltušnikas, A., & Yousef, S. (2025). Transforming Waste into Value: The Role of Recovered Carbon Fibre and Oil Shale Ash in Enhancing Cement-Based Structural Composites. Materials, 18(24), 5636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245636