Cytocompatibility and Microbiological Effects of Ti6Al4V Particles Generated During Implantoplasty on Human Fibroblasts, Osteoblasts, and Multispecies Oral Biofilm

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Metallic Residues and Dental Implants

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. Cytotoxicity Evaluation

2.3.1. Indirect Assay

2.3.2. Direct Assay

2.4. Biofilm Formation with Particle Presence

2.4.1. Biofilm Formation

2.4.2. Biofilm Quantification

2.5. Cell-Bacteria Co-Cultures

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cytotoxicity Evaluation

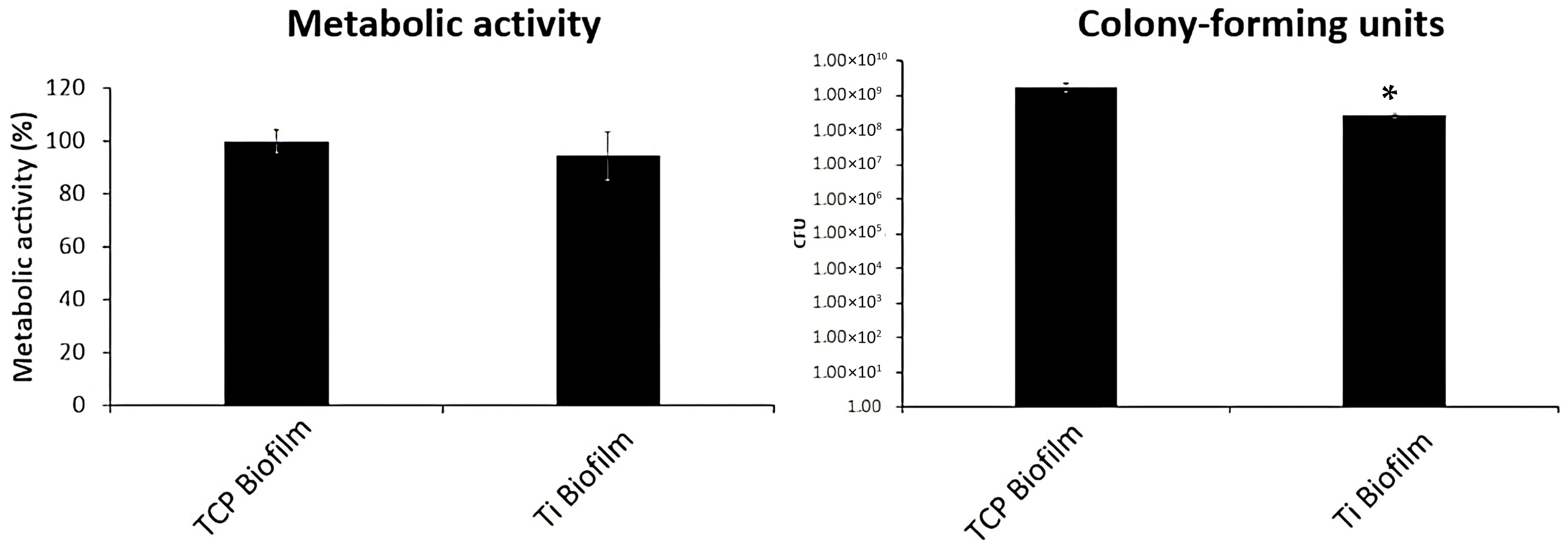

3.2. Biofilm Formation with Particle Presence

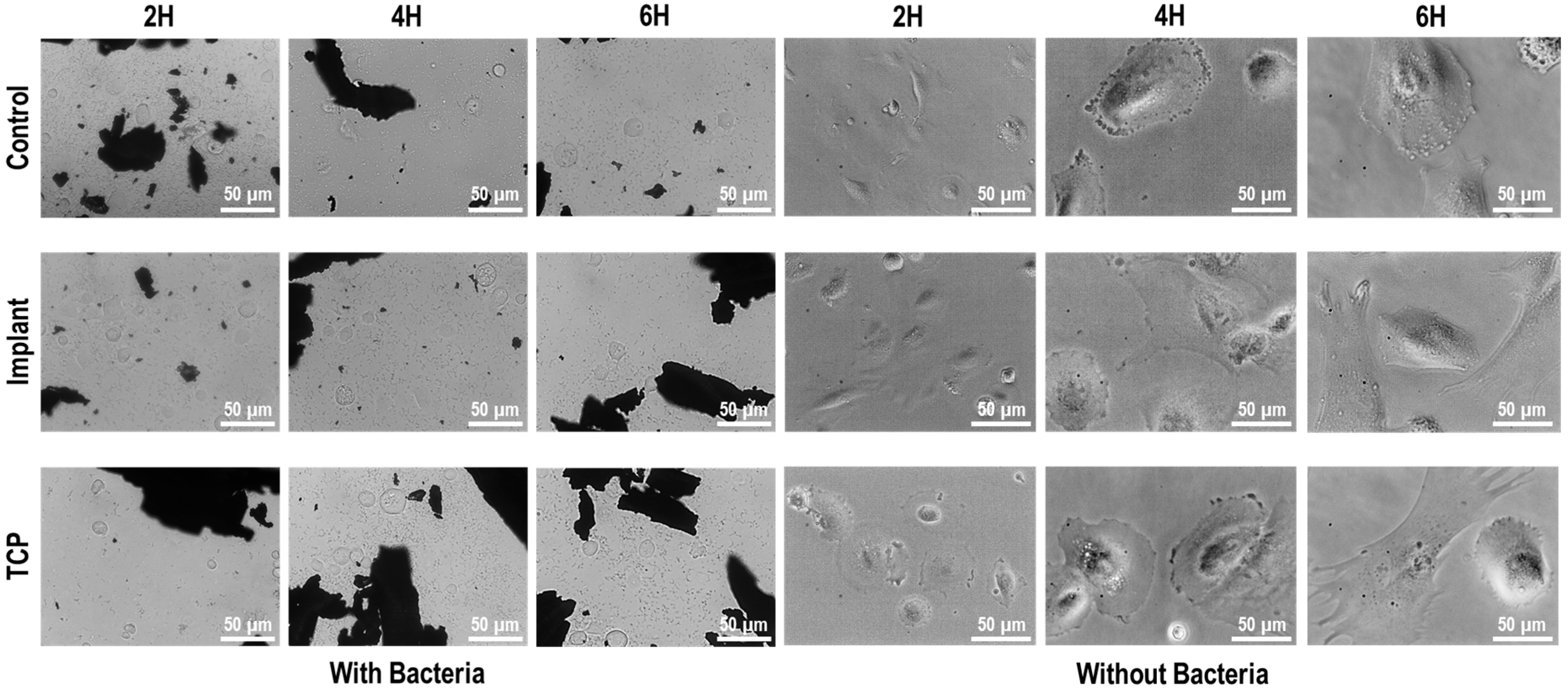

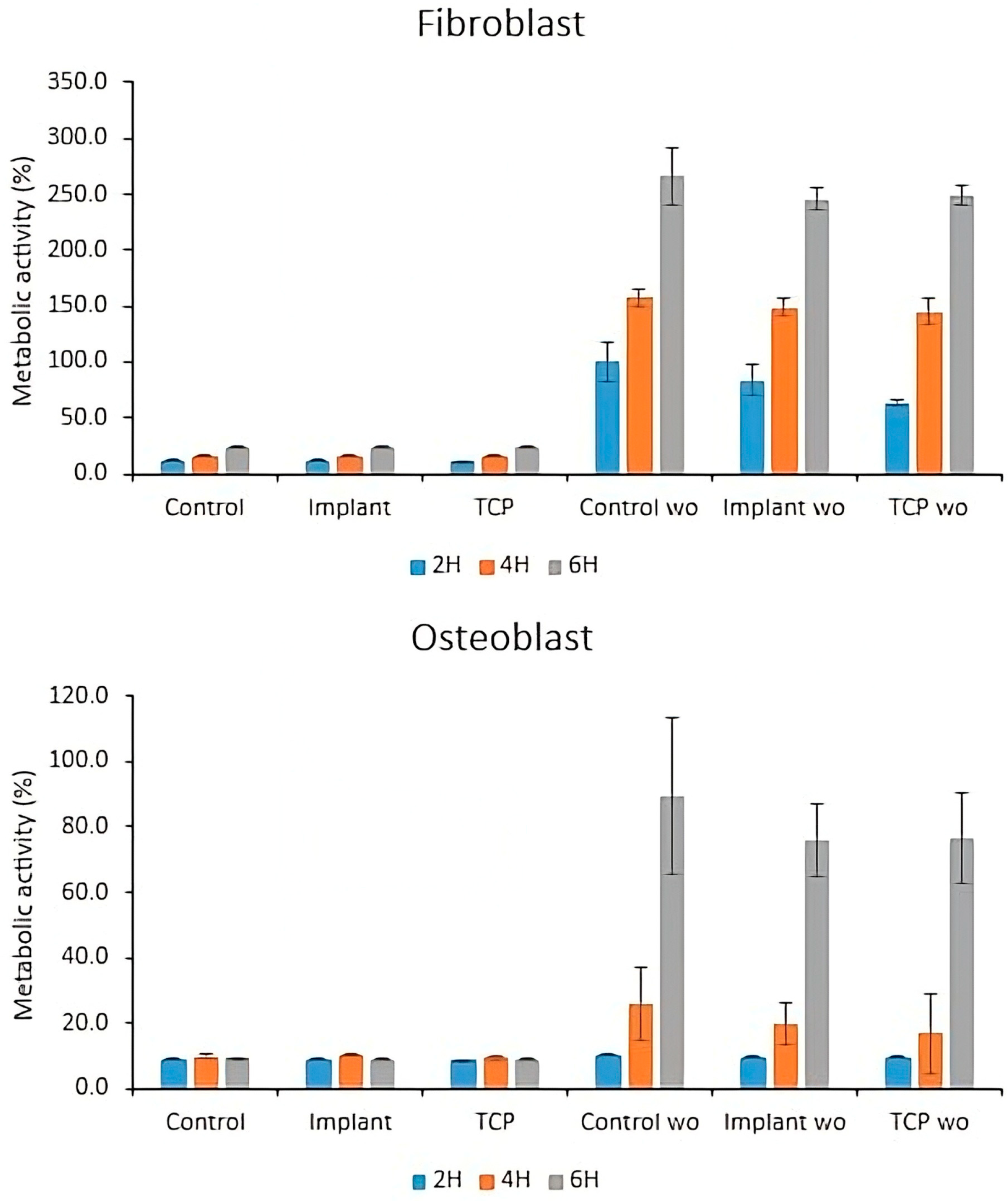

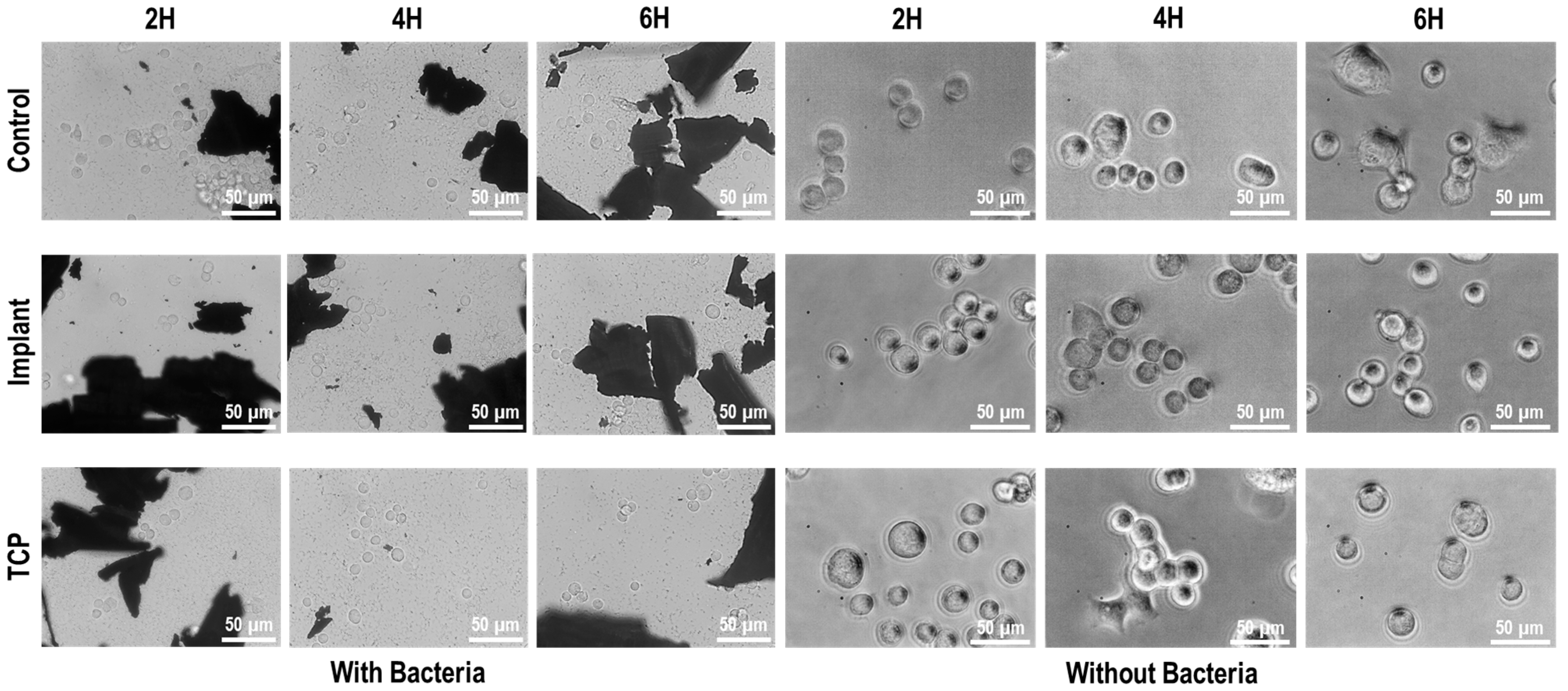

3.3. Cell-Bacteria Co-Culture

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IP | Implantoplasty |

| Ti | Titanium |

| Ti6Al4V | Titanium–Aluminum–Vanadium alloy |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| CFU | Colony-forming units |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| EDS | Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| P/S | Penicillin-Streptomycin |

| TCP | Tissue culture plastic |

| BHI | Brain–heart infusion |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| HFF-1 | Human foreskin fibroblasts |

| SaOs-2 | Osteoblast-like cells derived from human osteosarcoma |

| S. oralis | Streptococcus oralis |

| A. viscosus | Actinomyces viscosus |

| V. parvula | Veillonella parvula |

| P. gingivalis | Porphyromonas gingivalis |

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller theory |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| USA | United States of America |

References

- Barrak, F.N.; Li, S.; Muntane, A.M.; Jones, J.R. Particle release from implantoplasty of dental implants and impact on cells. Int. J. Implant. Dent. 2020, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedo, D.G.; Nalli, G.; Verdú, S.; Paparella, M.L.; Cabrini, R.L. Exfoliative cytology and titanium dental implants: A pilot study. J. Periodontol. 2013, 84, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halperin-Sternfeld, M.; Sabo, E.; Akrish, S. The pathogenesis of implant-related reactive lesions: A clinical, histologic and polarized light microscopy study. J. Periodontol. 2016, 87, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pegueroles, M.; Tonda-Turo, C.; Planell, J.A.; Gil, F.J.; Aparicio, C. Adsorption of fibronectin, fibrinogen, and albumin on TiO2: Time-resolved kinetics, structural changes, and competition study. Biointerphases 2012, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillem-Martí, J.; Delgado, L.; Godoy-Gallardo, M.; Pegueroles, M.; Herrero, M.; Gil, F.J. Fibroblast adhesion and activation onto micro-machined titanium surfaces. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2013, 24, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrak, F.; Li, S.; Muntane, A.; Bhatia, M.; Crossthwaite, K.; Jones, J. Particle release from dental implants immediately after placement—An ex vivo comparison of different implant systems. Den. Mater. 2022, 38, 1004–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzea, C.; Pacheco, II.; Robbie, K. Nanomaterials and nanoparticles: Sources and toxicity. Biointerphases 2007, 2, MR17–MR71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-López del Amo, F.; Garaicoa-Pazmiño, C.; Fretwurst, T.; Castilho, R.M.; Squarize, C.H. Dental implants-associated release of titanium particles: A systematic review. Clin. Oral. Implants Res. 2018, 29, 1085–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, M.; Kelk, P.; Belibasakis, G.N.; Bylund, D.; Molin Thorén, M.; Johansson, A. Titanium ions form particles that activate and execute interleukin-1β release from lipopolysaccharide-primed macrophages. J. Periodontal Res. 2017, 53, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, K.; Kato, T.; Ito, T.; Oda, T.; Sekine, H.; Yoshinari, M.; Yajima, Y. Influence of titanium ions on cytokine levels of murine splenocytes stimulated with periodontopathic bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Implant. 2014, 29, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, L.; Mao, Y.Q.; Dai, K.R.; Hao, Y.Q. Impaired autophagy in the fibroblasts by titanium particles increased the release of CX3CL1 and promoted the chemotactic migration of monocytes. Inflammation 2020, 43, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez-López del Amo, F.; Rudek, I.; Wagner, V.; Martins, M.D.; O’Valle, F.; Galindo-Moreno, P.; Giannobile, W.V.; Wang, H.L.; Castilho, R.M. Titanium activates the DNA damage response pathway in oral epithelial cells: A pilot study. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Implant. 2017, 32, 1413–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, F.; John, G.; Becker, J. The influence of implantoplasty on the diameter, chemical surface composition, and biocompatibility of titanium implants. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 2355–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figuero, E.; Graziani, F.; Sanz, I.; Herrera, D.; Sanz, M. Management of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis. Periodontology 2000 2014, 66, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgueño-Barris, G.; Camps-Font, O.; Figueiredo, R.; Valmaseda-Castellón, E. The Influence of implantoplasty on surface roughness, biofilm formation, and biocompatibility of titanium implants: A systematic review. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Implant. 2021, 36, e111–e119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramel, C.F.; Lüssi, A.; Özcan, M.; Jung, R.E.; Hämmerle, C.H.F.; Thoma, D.S. Surface roughness of dental implants and treatment time using six different implantoplasty procedures. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2016, 27, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batalha, V.C.; Bueno, R.A.; Fronchetti Junior, E.; Mariano, J.R.; Santin, G.C.; Freitas, K.M.S.; Ortiz, M.A.L.; Salmeron, S. Dental Implants Surface in vitro decontamination protocols. Eur. J. Dent. 2021, 15, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monje, A.; Pons, R.; Amerio, E.; Wang, H.L.; Nart, J. Resolution of peri-implantitis by means of implantoplasty as adjunct to surgical therapy: A retrospective study. J. Periodontol. 2022, 93, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, E.; Lops, D.; Chiapasco, M.; Ghisolfi, M.; Vogel, G. Therapy of peri-implantitis with resective surgery. A 3-year clinical trial on rough screw-shaped oral implants. Part II: Radiographic outcome. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2007, 18, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, E.; Ghisolfi, M.; Murgolo, N.; Chiapasco, M.; Lops, D.; Vogel, G. Therapy of peri-implantitis with resective surgery. A 3-year clinical trial on rough screw-shaped oral implants. Part I: Clinical outcome. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2005, 16, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camps-Font, O.; Toledano-Serrabona, J.; Juiz-Camps, A.; Gil, J.; Sánchez-Garcés, M.A.; Figueiredo, R.; Gay-Escoda, C.; Valmaseda-Castellón, E. Effect of implantoplasty on roughness, fatigue and corrosion behavior of narrow diameter dental implants. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitão-Almeida, B.; Camps-Font, O.; Correia, A.; Mir-Mari, J.; Figueiredo, R.; Valmaseda-Castellón, E. Effect of bone loss on the fracture resistance of narrow dental implants after implantoplasty. An in vitro study. Med. Oral. Patol. Oral. Cir. Bucal. 2021, 26, e611–e618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa-Berenguer, X.; García-García, M.; Sánchez-Torres, A.; Sanz-Alonso, M.; Figueiredo, R.; Valmaseda-Castellón, E. Effect of implantoplasty on fracture resistance and surface roughness of standard diameter dental implants. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2018, 29, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozano, P.; Peña, M.; Herrero-Climent, M.; Rios-Santos, J.V.; Rios-Carrasco, B.; Brizuela, A.; Gil, J. Corrosion behavior of titanium dental implants with implantoplasty. Materials 2022, 15, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, D.; de Tapia, B.; Pons, R.; Aparicio, C.; Guerra, F.; Messias, A.; Gil, J. The effect of implantoplasty on the fatigue behavior and corrosion resistance in titanium dental implants. Materials 2024, 17, 2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledano-Serrabona, J.; Gil, F.J.; Camps-Font, O.; Valmaseda-Castellón, E.; Gay-Escoda, C.; Sánchez-Garcés, M.Á. Physicochemical and biological characterization of ti6al4v particles obtained by implantoplasty: An in vitro study. Part I. Materials 2021, 14, 6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledano-Serrabona, J.; Sánchez-Garcés, M.A.; Gay-Escoda, C.; Valmaseda-Castellón, E.; Camps-Font, O.; Verdeguer, P.; Molmeneu, M.; Gil, F.J. Mechanical properties and corrosion behavior of Ti6Al4V particles obtained by implantoplasty: An in vitro study. Part II. Materials 2021, 14, 6519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, S.; Agnihotri, R.; Albin, S. Bio-Tribocorrosion of titanium dental implants and its toxicological implications: A scoping review. Sci. World J. 2022, 2022, 4498613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, F.J.; Rodriguez, A.; Espinar, E.; Llamas, J.M.; Padullés, E.; Juárez, A. Effect of oral bacteria on the mechanical behavior of titanium dental implants. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2012, 27, 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Beheshti Maal, M.; Aanerød Ellingsen, S.; Reseland, J.E.; Verket, A. Experimental implantoplasty outcomes correlate with fibroblast growth in vitro. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, S.; Lasserre, J.; Brecx, M.C.; Nyssen-Behets, C. In vitro evaluation of peri-implantitis treatment modalities on Saos-2osteoblasts. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2016, 27, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, F.; Langer, M.; Hagena, T.; Hartig, B.; Sader, R.; Becker, J. Cytotoxicity and proinflammatory effects of titanium and zirconia particles. Int. J. Implant. Dent. 2019, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camps-Font, O.; González-Barnadas, A.; Mir-Mari, J.; Figueiredo, R.; Gay-Escoda, C.; Valmaseda-Castellón, E. Fracture resistance after implantoplasty in three implant-abutment connection designs. Med. Oral. Patol. Oral. Cir. Bucal. 2020, 25, e691–e699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 10993-5; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices. Part 5. Test for In Vitro Cytotoxicity. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Vilarrasa, J.; Delgado, L.M.; Galofré, M.; Àlvarez, G.; Violant, D.; Manero, J.M.; Blanc, V.; Gil, F.J.; Nart, J. In vitro evaluation of a multispecies oral biofilm over antibacterial coated titanium surfaces. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2018, 29, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noronha Oliveira, M.; Schunemann, W.V.H.; Mathew, M.T.; Henriques, B.; Magini, R.S.; Teughels, W.; Souza, J.C.M. Can degradation products released from dental implants affect peri-implant tissues? J. Periodontal Res. 2018, 53, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violant, D.; Galofré, M.; Nart, J.; Teles, R.P. In vitro evaluation of a multispecies oral biofilm on different implant surfaces. Biomed. Mater. 2014, 9, 035007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.C.; Henriques, M.; Oliveira, R.; Teughels, W.; Celis, J.P.; Rocha, L.A. Do oral biofilms influence the wear and corrosion behavior of titanium? Biofouling 2010, 26, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy-Gallardo, M.; Guillem-Marti, J.; Sevilla, P.; Manero, J.M.; Gil, F.J.; Rodriguez, D. Anhydride-functional silane immobilized onto titanium surfaces induces osteoblast cell differentiation and reduces bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2016, 59, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu-Yuan, D.; Eganhouse, K.J.; Keller, J.C.; Walters, K.S. Oral bacterial attachment to titanium surfaces: A scanning electron microscopy study. J. Oral Implantol. 1995, 21, 207–213. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, M.C.; Llama-Palacios, A.; Fernández, E.; Figuero, E.; Marín, M.J.; León, R.; Blanc, V.; Herrera, D.; Sanz, M. An in vitro biofilm model associated to dental implants: Structural and quantitative analysis of in vitro biofilm formation on different dental implant surfaces. Dent. Mater. 2014, 30, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy-Gallardo, M.; Wang, Z.; Shen, Y.; Manero, J.M.; Gil, F.J.; Rodriguez, D.; Haapasalo, M. Antibacterial coatings on titanium surfaces: A Comparison study between in vitro single-species and multispecies biofilm. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 5992–6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bürgers, R.; Gerlach, T.; Hahnel, S.; Schwarz, F.; Handel, G.; Gosau, M. In vivo and in vitro biofilm formation on two different titanium implant surfaces. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2010, 21, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teughels, W.; Van Assche, N.; Sliepen, I.; Quirynen, M. Effect of material characteristics and/or surface topography on biofilm development. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2006, 17, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Insua, A.; Monje, A.; Wang, H.L.; Miron, R.J. Basis of bone metabolism around dental implants during osseointegration and peri-implant bone loss. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2017, 105, 2075–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köunönen, M.; Hormia, M.; Kivilahti, J.; Hautaniemi, J.; Thesleff, I. Effect of surface processing on the attachment, orientation, and proliferation of human gingival fibroblasts on titanium. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1992, 26, 1325–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nothdurft, F.P.; Fontana, D.; Ruppenthal, S.; May, A.; Aktas, C.; Mehraein, Y.; Lipp, P.; Kaestner, L. Differential behavior of fibroblasts and epithelial cells on structured implant abutment materials: A comparison of materials and surface topographies. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2015, 17, 1237–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pae, A.; Lee, H.; Kim, H.S.; Kwon, Y.D.; Woo, Y.H. Attachment and growth behaviour of human gingival fibroblasts on titanium and zirconia ceramic surfaces. Biomed. Mater. 2009, 4, 025005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, F.; Derks, J.; Monje, A.; Wang, H.L. Peri-implantitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, S246–S266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callejas, J.A.; Gil, J.; Brizuela, A.; Pérez, R.A.; Bosch, B.M. Effect of the size of titanium particles released from dental implants on immunological response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, A.; Pawar, V.; McAllister, K.; Weaver, C.; Hallab, N.J. Orthopedic implant cobalt-alloy particles produce greater toxicity and inflammatory cytokines than titanium alloy and zirconium alloy-based particles in vitro, in human osteoblasts, fibroblasts, and macrophages. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2012, 100, 2147–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranov, M.V.; Kumar, M.; Sacanna, S.; Thutupalli, S.; van den Bogaart, G. Modulation of immune responses by particle size and shape. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 607945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, K.; Hou, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Luo, Z.; Shi, Y.; Lai, M.; Yang, W.; Liu, P. Correlation of the cytotoxicity of TiO2 nanoparticles with different particle sizes on a sub-200-nm scale. Small 2011, 7, 3026–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, J.; Li, S.; Crean, S.J.; Barrak, F.N. Is titanium alloy Ti-6Al-4 V cytotoxic to gingival fibroblasts—A systematic review. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2021, 7, 1037–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asa′ad, F.; Thomsen, P.; Kunrath, M.F. The role of titanium particles and ions in the pathogenesis of peri-Implantitis. J. Bone Metab. 2022, 29, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vegas-Bustamante, E.; Toledano-Serrabona, J.; Sánchez-Garcés, M.Á.; Figueiredo, R.; Demiquels-Punzano, E.; Gil, J.; Delgado, L.M.; Sanmartí-García, G.; Camps-Font, O. Cytocompatibility and Microbiological Effects of Ti6Al4V Particles Generated During Implantoplasty on Human Fibroblasts, Osteoblasts, and Multispecies Oral Biofilm. Materials 2025, 18, 5626. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245626

Vegas-Bustamante E, Toledano-Serrabona J, Sánchez-Garcés MÁ, Figueiredo R, Demiquels-Punzano E, Gil J, Delgado LM, Sanmartí-García G, Camps-Font O. Cytocompatibility and Microbiological Effects of Ti6Al4V Particles Generated During Implantoplasty on Human Fibroblasts, Osteoblasts, and Multispecies Oral Biofilm. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5626. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245626

Chicago/Turabian StyleVegas-Bustamante, Erika, Jorge Toledano-Serrabona, María Ángeles Sánchez-Garcés, Rui Figueiredo, Elena Demiquels-Punzano, Javier Gil, Luis M. Delgado, Gemma Sanmartí-García, and Octavi Camps-Font. 2025. "Cytocompatibility and Microbiological Effects of Ti6Al4V Particles Generated During Implantoplasty on Human Fibroblasts, Osteoblasts, and Multispecies Oral Biofilm" Materials 18, no. 24: 5626. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245626

APA StyleVegas-Bustamante, E., Toledano-Serrabona, J., Sánchez-Garcés, M. Á., Figueiredo, R., Demiquels-Punzano, E., Gil, J., Delgado, L. M., Sanmartí-García, G., & Camps-Font, O. (2025). Cytocompatibility and Microbiological Effects of Ti6Al4V Particles Generated During Implantoplasty on Human Fibroblasts, Osteoblasts, and Multispecies Oral Biofilm. Materials, 18(24), 5626. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245626