The Effect of Shavings from 3D-Printed Patient-Specific Cutting Guide Materials During Jaw Resection on Bone Healing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Cutting Guide Materials

2.2. Preparation of the Material Shavings

2.3. SEM Imaging

2.4. Cell Culture

2.5. Cell Proliferation Assay

2.6. Animals

2.7. Calvarial Bone Defect Assay

2.8. Micro-CT Analysis

2.9. Histomorphometric Analysis

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. In Vitro Assessment of the 3D-Printed Cutting Guide Materials

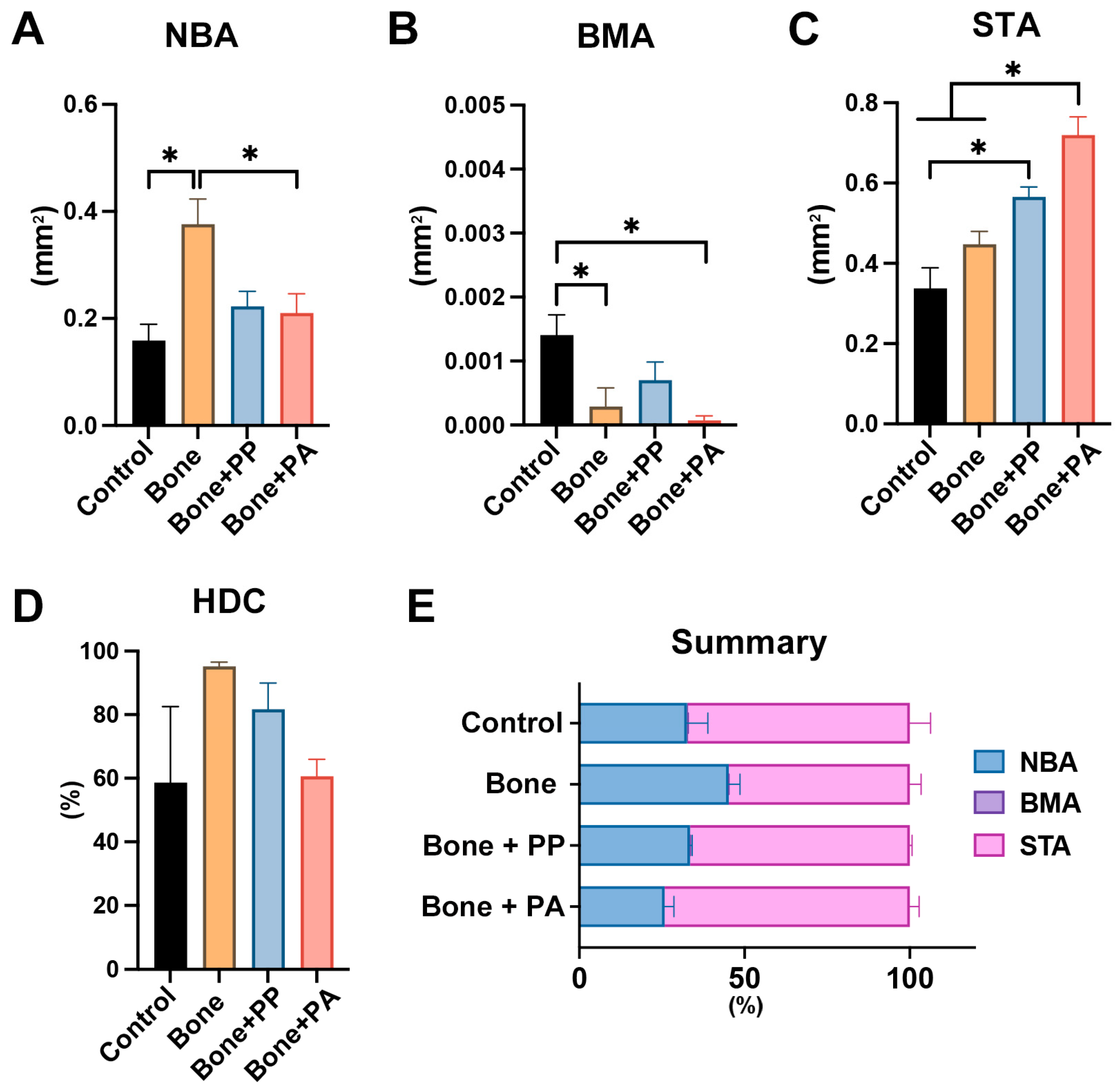

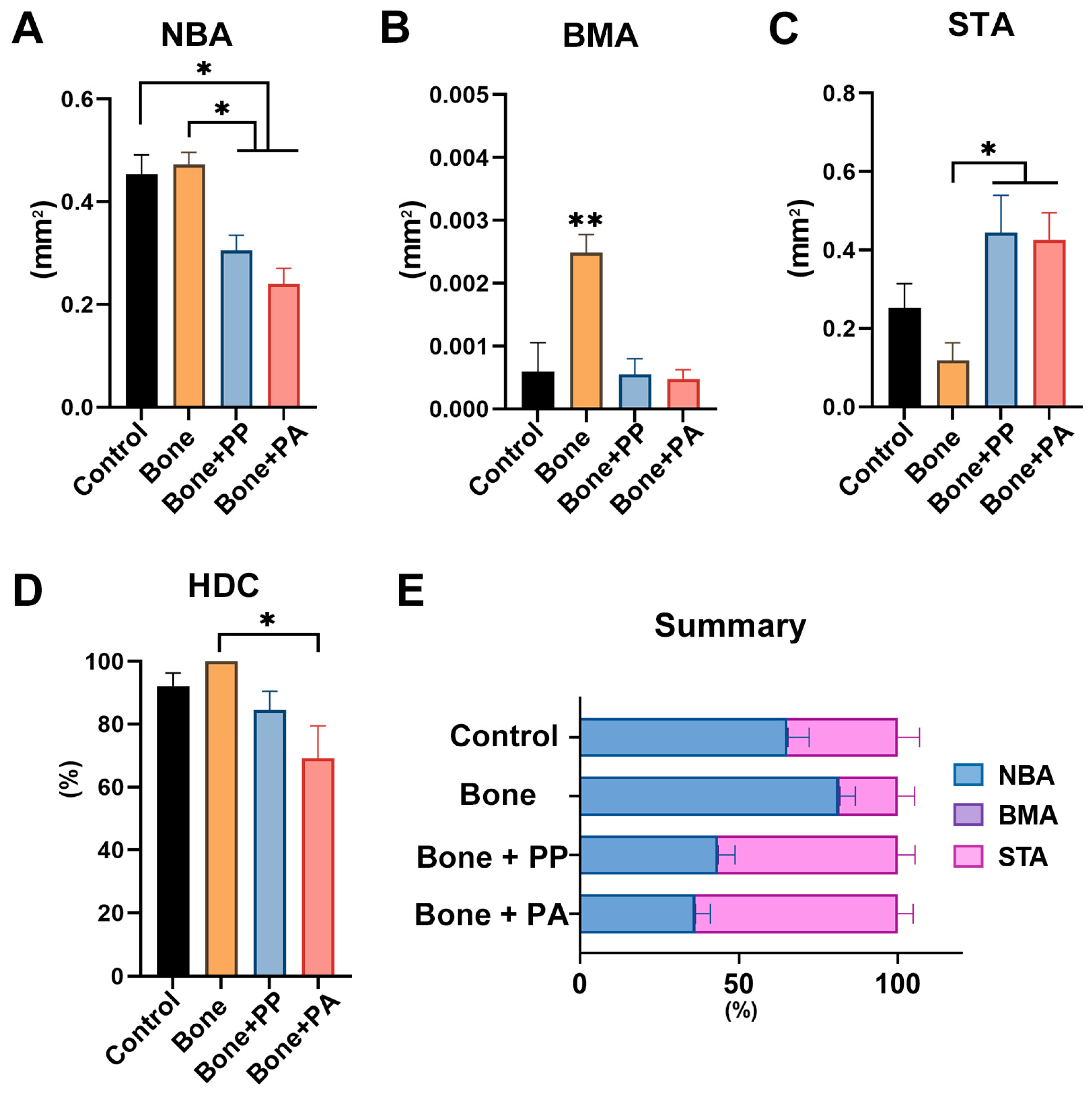

3.2. In Vivo Assessment of the 3D-Printed Cutting Guide Materials During Bone Healing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PP | Photopolymer resin |

| PA | Polyamide resin |

| CAD/CAM | Computer-aided design/manufacturing |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| CAS | Computer-aided surgery |

| VPP | Vat photopolymerization |

| PBF | Powder bed fusion |

| SLA | Stereolithography |

| SLS | Selective laser sintering |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| NBA | New bone area |

| NBV | New bone volume |

| BMD | Bone mineral density |

| BMA | Bone marrow area |

| STA | Soft/connective tissue area |

| HDC | Horizontal defect closure |

| VOI | Volume of interest |

| ROI | Region of interest |

References

- Kanumilli, S.L.D.; Kosuru, B.P.; Shaukat, F.; Repalle, U.K. Advancements and Applications of Three-dimensional Printing Technology in Surgery. J. Med. Phys. 2024, 49, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.H.C.; Kui, C.; Lee, E.K.M.; Ho, C.S.; Wong, S.H.; Wu, W.; Wong, W.T.; Voll, J.; Li, G.; Liu, T.; et al. The role of 3D printing in anatomy education and surgical training: A narrative review. MedEdPublish 2017, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annino, D.J., Jr.; Sethi, R.K.; Hansen, E.E.; Horne, S.; Dey, T.; Rettig, E.M.; Uppaluri, R.; Kass, J.I.; Goguen, L.A. Virtual planning and 3D-printed guides for mandibular reconstruction: Factors impacting accuracy. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2022, 7, 1798–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Mu, M.; Yan, J.; Han, B.; Ye, R.; Guo, G. 3D printing materials and 3D printed surgical devices in oral and maxillofacial surgery: Design, workflow and effectiveness. Regen. Biomater. 2024, 11, rbae066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copelli, C.; Cacciatore, F.; Cocis, S.; Maglitto, F.; Barbara, F.; Iocca, O.; Manfuso, A. Bone reconstruction using CAD/CAM technology in head and neck surgical oncology. A narrative review of state of the art and aesthetic-functional outcomes. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2024, 44 (Suppl. 1), S58–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, F.; Hanken, H.; Probst, F.; Schramm, A.; Heiland, M.; Cornelius, C.-P. Multicenter study on the use of patient-specific CAD/CAM reconstruction plates for mandibular reconstruction. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2015, 10, 2035–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, P.; Zaborniak, M.; Grzywacz-Danielewicz, K.; Bałuszyński, M.; Lewandowski, B.; Kluczyński, J.; Daniel, N. A Review of the Most Commonly Used Additive Manufacturing Techniques for Improving Mandibular Resection and Reconstruction Procedures. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, S.I.; Bud, E.; Jánosi, K.M.; Bud, A.; Kerekes-Máthé, B. Three-Dimensional Surgical Guides in Orthodontics: The Present and the Future. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, D.H.; Mills, P.; Duszak, R., Jr.; Weisman, J.A.; Rybicki, F.J.; Woodard, P.K. Medical 3D Printing Cost-Savings in Orthopedic and Maxillofacial Surgery: Cost Analysis of Operating Room Time Saved with 3D Printed Anatomic Models and Surgical Guides. Acad. Radiol. 2020, 27, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, J.M.; Daly, M.J.; Chan, H.; Qiu, J.; Goldstein, D.; Muhanna, N.; de Almeida, J.R.; Irish, J.C. Accuracy and reproducibility of virtual cutting guides and 3D-navigation for osteotomies of the mandible and maxilla. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosc, R.; Hersant, B.; Carloni, R.; Niddam, J.; Bouhassira, J.; De Kermadec, H.; Bequignon, E.; Wojcik, T.; Julieron, M.; Meningaud, J.-P. Mandibular reconstruction after cancer: An in-house approach to manufacturing cutting guides. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 46, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, J.; Shenoy, M.; Alhasmi, A.; Al Saleh, A.A.; Shivakumar, S.; Alsaleh, A.A., Jr. Biocompatibility of 3D-Printed Dental Resins: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e51721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, M.; Jubeli, E.; Pungente, M.D.; Yagoubi, N. Biocompatibility of polymer-based biomaterials and medical devices–regulations, in vitro screening and risk-management. Biomater. Sci. 2018, 6, 2025–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thangaraju, P.; Varthya, S.B. ISO 10993: Biological evaluation of medical devices. In Medical Device Guidelines and Regulations Handbook; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 163–187. [Google Scholar]

- Sudo, H.; Kodama, H.A.; Amagai, Y.; Yamamoto, S.; Kasai, S. In vitro differentiation and calcification in a new clonal osteogenic cell line derived from newborn mouse calvaria. J. Cell Biol. 1983, 96, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, T.; Miyauchi, M.; Wang, H.L. Migration of osteoblastic cells on various guided bone regeneration membranes. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2001, 12, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdfelder, E.; Faul, F.; Buchner, A. GPOWER: A general power analysis program. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 1996, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadad, H.; Boos Lima, F.B.; Shirinbak, I.; Porto, T.S.; Chen, J.E.; Guastaldi, F.P. The impact of 3D printing on oral and maxillofacial surgery. J. 3D Print. Med. 2023, 7, 3DP007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annino, D.J., Jr.; Hansen, E.E.; Sethi, R.K.; Horne, S.; Rettig, E.M.; Uppaluri, R.; Goguen, L.A. Accuracy and outcomes of virtual surgical planning and 3D-printed guides for osseous free flap reconstruction of mandibular osteoradionecrosis. Oral Oncol. 2022, 135, 106239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkh, H.A.; Makhoul, N. In-house surgeon-led virtual surgical planning for maxillofacial reconstruction. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 78, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujioka-Kobayashi, M.; Miyasaka, A.; Inada, R.; Koyanagi, M.; Tsunoda, E.; Satomi, T. Custom-made surgical guide with mucoperiosteal flap elevation function for the removal of multiple impacted supernumerary teeth: A case report. Oral Sci. Int. 2025, 22, e1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, Y.; Uzawa, N. Current status and prospects of computer-assisted surgery (CAS) in oral and maxillofacial reconstruction. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, C.; Boudreau, C.; Prabhu, N.; Hong, P.; Bezuhly, M. Piezosurgery versus conventional cutting techniques in craniofacial surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2022, 149, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohn, B.M.; Raith, S.; Ooms, M.; Winnand, P.; Hölzle, F.; Modabber, A. Comparison of the accuracy of different slot properties of 3D-printed cutting guides for raising free fibular flaps using saw or piezoelectric instruments: An in vitro study. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2025, 20, 2501–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, H.; Zhang, T.; Xu, H.; Luo, S.; Nie, J.; Zhu, X. Photo-curing 3D printing technique and its challenges. Bioact. Mater. 2020, 5, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiertelak-Makała, K.; Szymczak-Pajor, I.; Bociong, K.; Śliwińska, A. Considerations about cytotoxicity of resin-based composite dental materials: A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasuya, S.; Kato-Kogoe, N.; Omori, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Taguchi, S.; Fujita, H.; Imagawa, N.; Sunano, A.; Inoue, K.; Ito, Y.; et al. New Bone Formation Process Using Bio-Oss and Collagen Membrane for Rat Calvarial Bone Defect: Histological Observation. Implant. Dent. 2018, 27, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsunoda, E.; Fujioka-Kobayashi, M.; Koyanagi, M.; Arai, Y.; Inomata, T.; Inada, R.; Satomi, T. The Effect of Shavings from 3D-Printed Patient-Specific Cutting Guide Materials During Jaw Resection on Bone Healing. Materials 2025, 18, 5624. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245624

Tsunoda E, Fujioka-Kobayashi M, Koyanagi M, Arai Y, Inomata T, Inada R, Satomi T. The Effect of Shavings from 3D-Printed Patient-Specific Cutting Guide Materials During Jaw Resection on Bone Healing. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5624. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245624

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsunoda, Erina, Masako Fujioka-Kobayashi, Masateru Koyanagi, Yuichiro Arai, Toru Inomata, Ryo Inada, and Takafumi Satomi. 2025. "The Effect of Shavings from 3D-Printed Patient-Specific Cutting Guide Materials During Jaw Resection on Bone Healing" Materials 18, no. 24: 5624. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245624

APA StyleTsunoda, E., Fujioka-Kobayashi, M., Koyanagi, M., Arai, Y., Inomata, T., Inada, R., & Satomi, T. (2025). The Effect of Shavings from 3D-Printed Patient-Specific Cutting Guide Materials During Jaw Resection on Bone Healing. Materials, 18(24), 5624. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245624