Comparison of Cutting Efficiency Between Natural and Synthetic Diamond-Coated Burs on Zirconia and Natural Teeth

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Diamond Rotary Instruments

2.2. Specimen Preparation

2.2.1. Zirconia Specimens

2.2.2. Natural Tooth Specimens

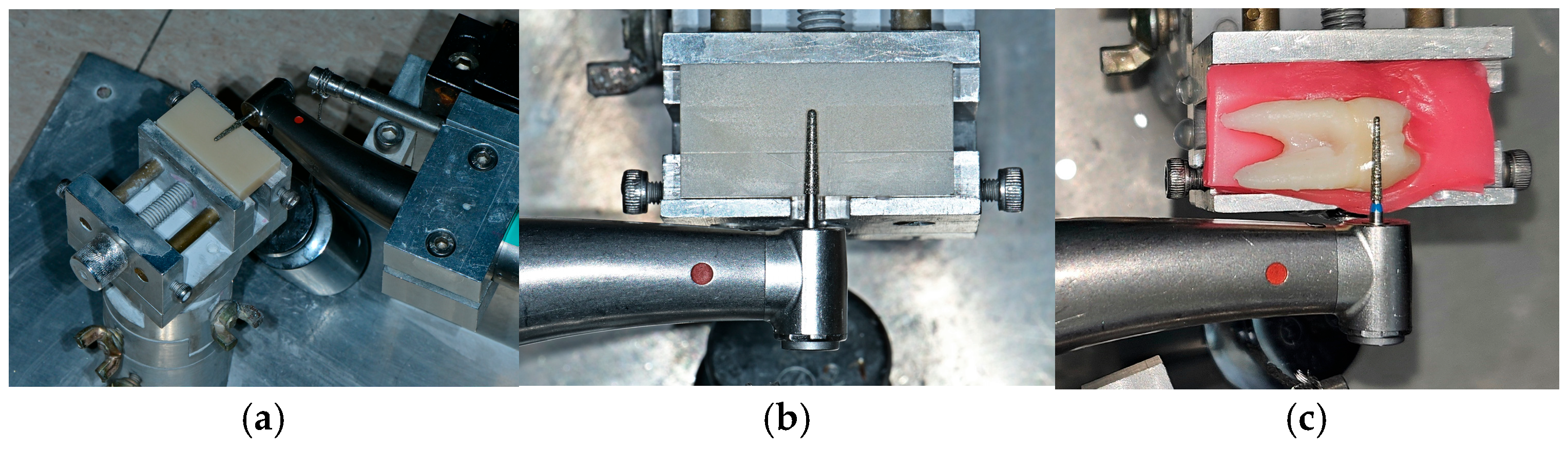

2.3. Cutting Efficiency Experiment

2.3.1. Experimental Setup

2.3.2. Cutting Protocol

- 1.

- Pre-cutting measurement: Each specimen was weighed using a precision electronic balance (PAG214C; Ohaus, Parsippany, NJ, USA; accuracy ± 0.001 g).

- 2.

- Cutting conditions: All burs were operated at 200,000 rpm under continuous water coolant (25 mL/min). The maximum speed was confirmed on the Elec LED display. The same high-speed turbine handpiece (T2 Line A 200L; Dentsply Sirona, York, PA, USA) was used throughout the experiment to ensure consistent conditions across all specimens.

- 3.

- Post-cutting procedure: After each cycle, specimens were rinsed with distilled water, ultrasonically cleaned (SHB-1025; Sehansonic, Seoul, Republic of Korea) to remove debris, air-dried for 30 s, and re-weighed. Cutting efficiency was calculated as weight loss per unit time (mg/min).

- 4.

- Sequential cutting: Each diamond bur was used 10 consecutive cutting cycles on 10 separate specimens. Between cycles, lubricant (KaVo Quattrocare Plus; KaVo, Biberach, Germany) was applied for 1 s, and the handpiece was operated without load for 1 min to remove residual lubricant.

- 5.

- Experimental repetition: The full protocol was repeated with new burs (n = 10), producing 100 cutting measurements per specimen type and bur group.

2.3.3. Evaluation Parameters

- Cutting efficiency: Weight difference before and after cutting (mg/min).

- Total cutting efficiency: Cumulative value from the 1st to 10th cycles, representing the overall cutting performance of each instrument.

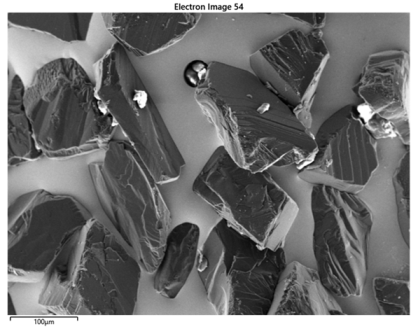

2.4. Surface Characterization Methods

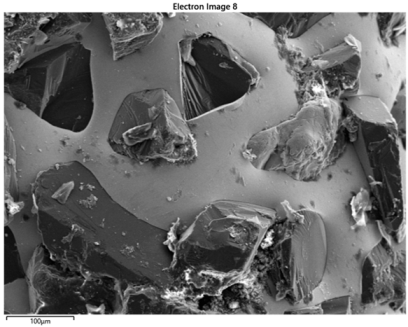

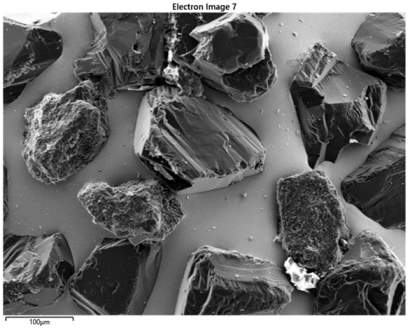

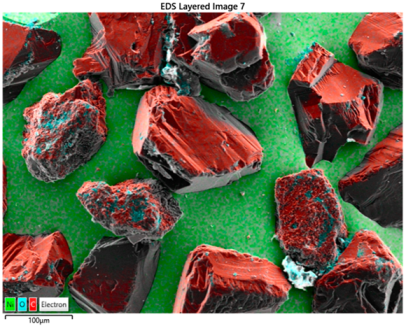

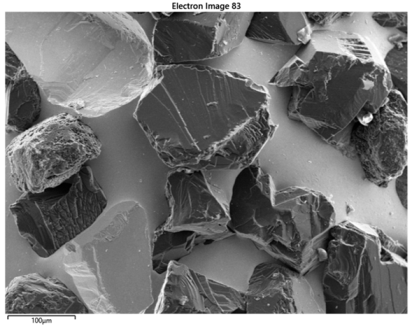

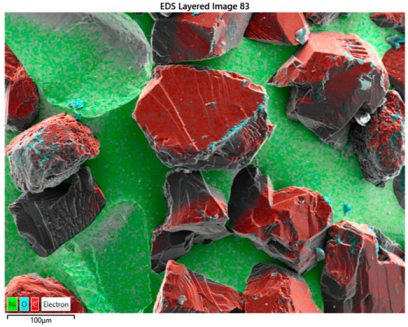

2.4.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

- Diamond bur analysis: New (unused) and used (after 10 cycles) burs from both groups were observed at ×200 magnification. Qualitative observations included:

- ∘

- Diamond particle size, shape, and morphology.

- ∘

- Wear patterns and structural damage.

- ∘

- Diamond particle dislodgement or attrition.

- Cutting surface analysis: Representative zirconia and enamel specimens were examined at ×100–×1000 magnification to assess:

- ∘

- Microstructural features of the central cut area.

- ∘

- Characteristics of the cut–uncut boundary.

- ∘

- Presence of thermal damage or debris accumulation.

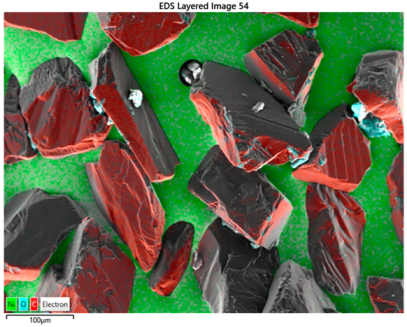

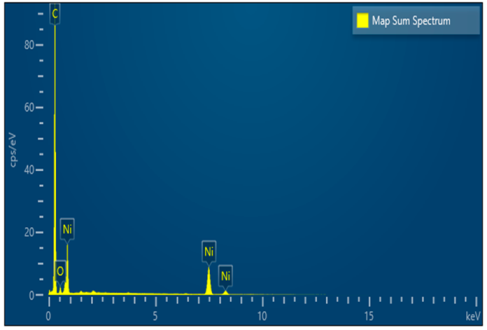

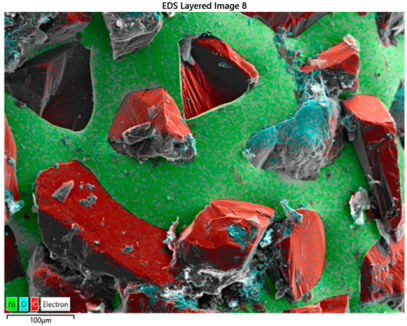

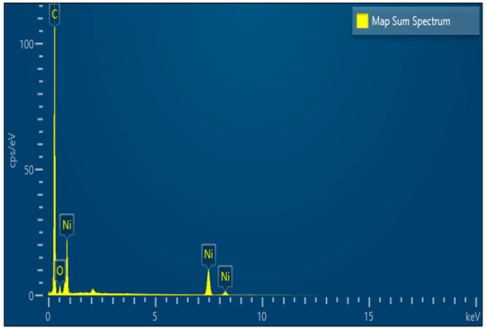

2.4.2. Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS)

- Carbon (C): representing diamond particles.

- Nickel (Ni): representing the metal matrix.

- Oxygen (O): indicating possible oxidation or contamination.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cutting Efficiency Experiment

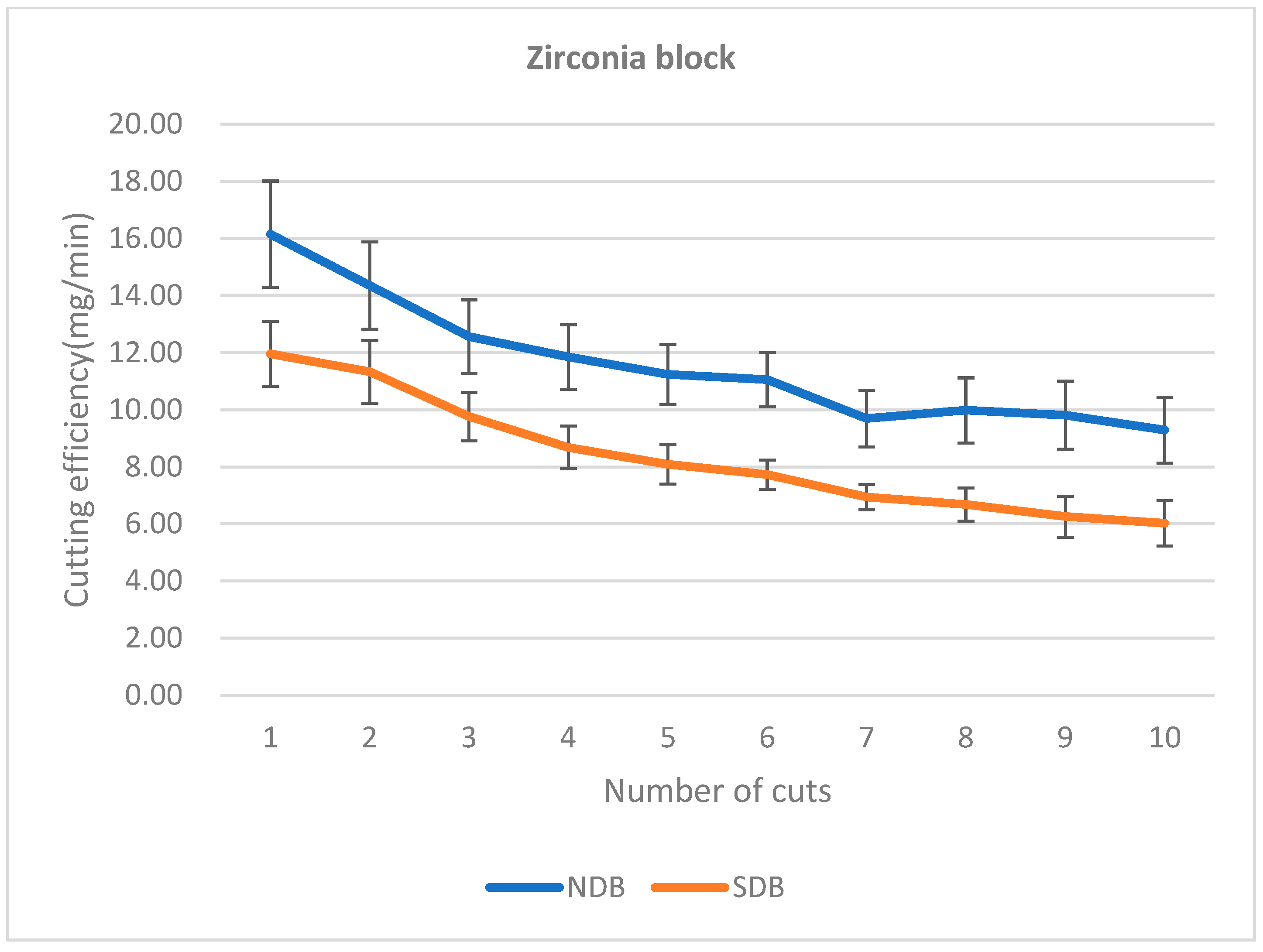

3.1.1. Zirconia Block Cutting Efficiency

- Cutting Efficiency by Number of Cuts

- Total Cutting Efficiency

- Cutting Efficiency Reduction Rate

3.1.2. Natural Tooth Cutting Efficiency

- Cutting Efficiency by Number of Cuts

- Total Cutting Efficiency

- Cutting Efficiency Reduction Rate

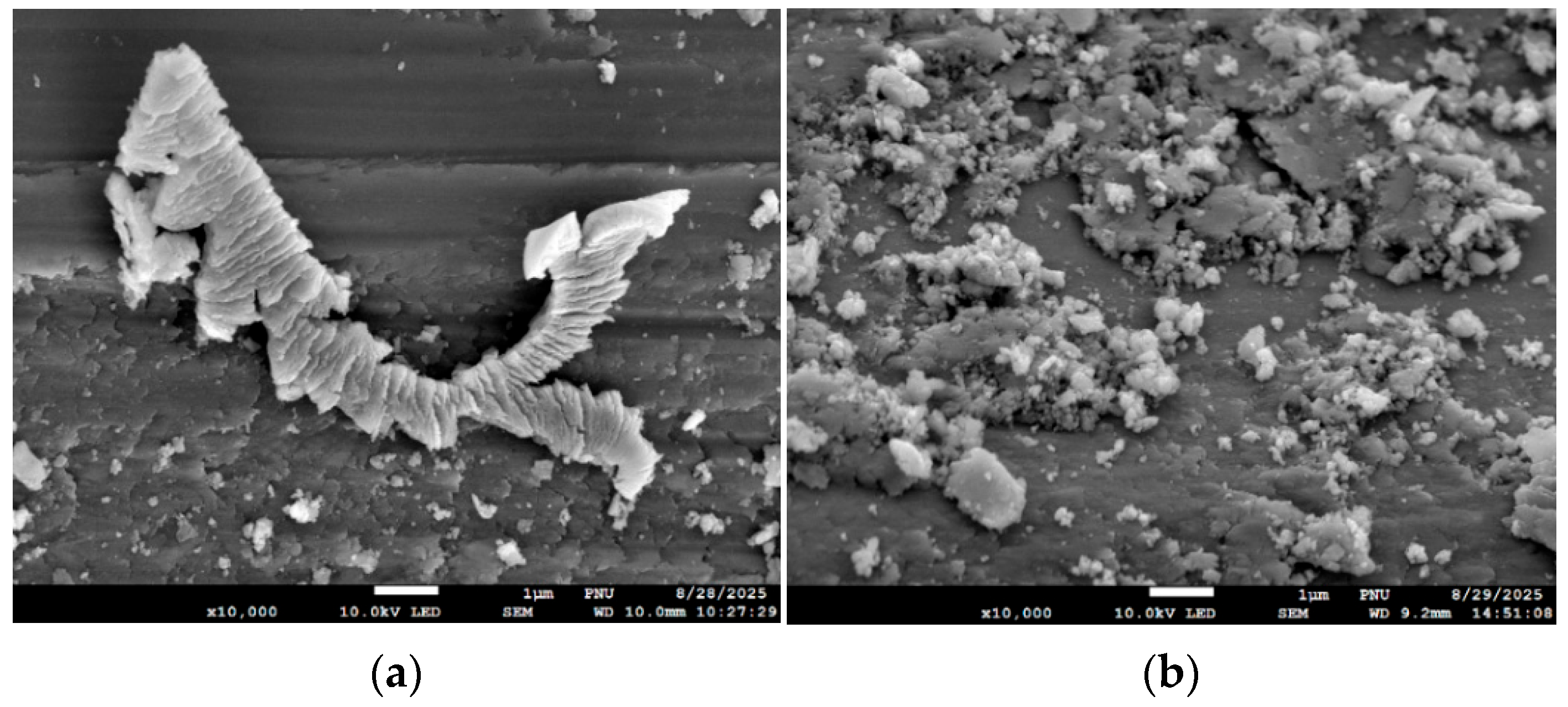

3.2. Surface Characterization

3.2.1. Surface Characteristics of Diamond Burs

- Carbon Content Changes

- Nickel Content Changes

- Oxygen Content Changes

- Standard Deviation Changes

3.2.2. Cutting Surface Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NDB | Natural diamond burs |

| SDB | Synthetic diamond burs |

| EDS | Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy |

| FE-SEM | Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| HPHT | High-Pressure High-Temperature |

| CVD | Chemical Vapor Deposition |

| LTD | Low-Temperature Degradation |

References

- Agustín-Panadero, R.; Roman-Rodriguez, J.; Ferreiroa, A.; Sola-Ruiz, M.; Fons-Font, A. Zirconia in fixed prosthesis. A literature review. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2014, 6, e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apratim, A.; Eachempati, P.; Salian, K.K.; Singh, V.; Chhabra, S.; Shah, S. Zirconia in dental implantology: A review. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2015, 5, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvie, R.C.; Hannink, R.; Pascoe, R. Ceramic steel? In Sintering Key Papers; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1990; pp. 253–257. [Google Scholar]

- Piconi, C.; Maccauro, G. Zirconia as a ceramic biomaterial. Biomaterials 1999, 20, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pjetursson, B.E.; Valente, N.A.; Strasding, M.; Zwahlen, M.; Liu, S.; Sailer, I. A systematic review of the survival and complication rates of zirconia-ceramic and metal-ceramic single crowns. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2018, 29, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libby, G.; Arcuri, M.R.; LaVelle, W.E.; Hebl, L. Longevity of fixed partial dentures. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1997, 78, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-S.; Bae, J.-H.; Yun, M.-J.; Huh, J.-B. In vitro assessment of cutting efficiency and durability of zirconia removal diamond rotary instruments. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2017, 117, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, J.-H.; Yi, J.; Kim, S.; Shim, J.-S.; Lee, K.-W. Changes in the cutting efficiency of different types of dental diamond rotary instrument with repeated cuts and disinfection. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2014, 111, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunziker, S.; Thorpe, L.; Zitzmann, N.U.; Rohr, N. Evaluation of diamond rotary instruments marketed for removing zirconia restorations. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 131, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aswegen, A.; Jagathpal, A.J.; Sykes, L.M.; Schoeman, H. A comparative study of the cutting efficiency of diamond rotary instruments with different grit sizes with a low-speed electric handpiece against zirconia specimens. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 131, 101.e1–101.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, S.C.; Von Fraunhofer, J.A. Cutting efficiency of three diamond bur grit sizes. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2000, 131, 1706–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzaga, C.C.; da Cunha, L.F.; Spina, D.R.F.; Bertoli, F.M.d.P.; Feres, R.L.; Fernandes, A.B.F. Cutting efficiency of different diamond burs after repeated cuts and sterilization cycles in autoclave. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2019, 30, 915–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Haenens-Johansson, U.F.; Butler, J.E.; Katrusha, A.N. Synthesis of diamonds and their identification. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2022, 88, 689–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, J.N.; Li, X.S. Microstructural characterisation and wear behaviour of diamond composite materials. Materials 2010, 3, 1390–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Ham, J.; Song, M.; Lee, C. The interfacial reaction between diamond grit and Ni-based brazing filler metal. Mater. Trans. 2007, 48, 889–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayakar, R.P.; Sethi, T.K.; Patil, A.G. Cutting Efficiency of Welded Diamond and Vacuum Diffusion Technology Burs and Conventional Electroplated Burs on the Surface Changes of the Teeth—An In vitro Study. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2021, 12, 251–257. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Smith, D.; Jahanmir, S.; Romberg, E.; Kelly, J.; Thompson, V.; Rekow, E. Indentation damage and mechanical properties of human enamel and dentin. J. Dent. Res. 1998, 77, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, R.G.; Peyton, F.A. The microhardness of enamel and dentin. J. Dent. Res. 1958, 37, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seghi, R.; Denry, I.; Rosenstiel, S. Relative fracture toughness and hardness of new dental ceramics. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1995, 74, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, J. What future for zirconia as a biomaterial? Biomaterials 2006, 27, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lughi, V.; Sergo, V. Low temperature degradation-aging-of zirconia: A critical review of the relevant aspects in dentistry. Dent. Mater. 2010, 26, 807–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, X.; Liang, S. The mechanism of ductile chip formation in cutting of brittle materials. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2007, 33, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inokoshi, M.; Zhang, F.; De Munck, J.; Minakuchi, S.; Naert, I.; Vleugels, J.; Van Meerbeek, B.; Vanmeensel, K. Influence of sintering conditions on low-temperature degradation of dental zirconia. Dent. Mater. 2014, 30, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohorst, P.; Borchers, L.; Strempel, J.; Stiesch, M.; Hassel, T.; Bach, F.-W.; Hübsch, C. Low-temperature degradation of different zirconia ceramics for dental applications. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 1213–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bompolaki, D.; Kontogiorgos, E.; Wilson, J.B.; Nagy, W.W. Fracture resistance of lithium disilicate restorations after endodontic access preparation: An in vitro study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2015, 114, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallya, J.; DuVall, N.; Brewster, J.; Roberts, H. Endodontic access effect on full contour zirconia and lithium disilicate failure resistance. Oper. Dent. 2020, 45, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, K.C.; Berzins, D.W.; Luo, Q.; Thompson, G.A.; Toth, J.M.; Nagy, W.W. Resistance to fracture of two all-ceramic crown materials following endodontic access. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2006, 95, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number of Cuts | NDB (mg) | SDB (mg) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st cycle | 16.15 ±4.38 ᴬ | 11.96 ± 1.94 ᴮ | 0.011 * |

| 2nd cycle | 14.35 ± 3.64 ᴬ | 11.33 ± 2.43 ᴮ | 0.035 * |

| 3rd cycle | 12.56 ± 3.34 ᴬ | 9.76 ± 2.02 ᴮ | 0.043 * |

| 4th cycle | 11.85 ± 3.08 ᴬ | 8.68 ± 2.16 ᴮ | 0.019 * |

| 5th cycle | 11.24 ± 3.09 ᴬ | 8.09 ± 2.21 ᴮ | 0.019 * |

| 6th cycle | 11.05 ± 2.91 ᴬ | 7.73 ± 1.68 ᴮ | 0.005 ** |

| 7th cycle | 9.69 ± 3.37 ᴬ | 6.94 ± 1.56 ᴮ | 0.015 * |

| 8th cycle | 9.98 ± 3.93 ᴬ | 6.68 ± 2.00 ᴮ | 0.019 * |

| 9th cycle | 9.81 ± 4.13 ᴬ | 6.26 ± 2.35 ᴮ | 0.023 * |

| 10th cycle | 9.29 ± 4.01 ᴬ | 6.03 ± 2.47 ᴮ | 0.029 * |

| Total cutting efficiency | 115.97 ± 2.22 ᴬ | 83.46 ± 2.08 ᴮ | <0.05 |

| Reduction rate | 40.00 ± 13.66% | 49.68 ± 18.97% | - |

| Number of Cuts | NDB (mg) | SDB (mg) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st cycle | 14.96 ± 5.48 | 17.23 ± 5.92 | 0.529 |

| 2nd cycle | 16.55 ± 5.91 | 17.59 ± 6.91 | 0.853 |

| 3rd cycle | 16.87 ± 3.67 | 19.68 ± 5.63 | 0.436 |

| 4th cycle | 16.17 ± 6.47 | 15.87 ± 4.98 | 0.853 |

| 5th cycle | 19.16 ± 8.73 | 17.65 ± 6.88 | 0.853 |

| 6th cycle | 16.30 ± 3.92 | 18.65 ± 5.37 | 0.143 |

| 7th cycle | 14.82 ± 2.45 | 17.72 ± 5.02 | 0.165 |

| 8th cycle | 15.85 ± 5.02 | 19.01 ± 7.64 | 0.353 |

| 9th cycle | 16.19 ± 4.82 | 15.86 ± 5.41 | 0.912 |

| 10th cycle | 14.61 ± 3.29 | 16.01 ± 5.82 | 0.579 |

| Total cutting efficiency | 161.48 ± 5.27 | 175.27 ± 6.02 | >0.05 |

| Reduction rate | 2.34% | 7.08% | - |

| SEM | EDS Layered Image | Map Sum Spectrum | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDB new |  |  |  | |

| NDB used |  |  |  | |

| SDB new |  |  |  | |

| SDB used |  |  |  | |

| Group | Condition | Carbon (wt%, mean ± SD) | Nickel (wt%, mean ± SD) | Oxygen (wt%, mean ± SD) |

| NDB | New | 65.676 ± 2.045 | 32.463 ± 2.040 | 1.860 ± 0.440 |

| NDB | Used | 63.988 ± 7.504 | 31.58 ± 6.673 | 4.432 ± 5.047 |

| NDB | Reduction (%) | 2.494 ± 11.844 | −150.359 ± 313.956 | 2.511 ± 19.978 |

| SDB | New | 77.845 ± 2.688 | 18.816 ± 2.956 | 3.339 ± 0.680 |

| SDB | Used | 67.845 ± 8.662 | 25.028 ± 9.076 | 7.477 ± 10.687 |

| SDB | Reduction (%) | 13.461 ± 9.607 | −141.335 ± 344.843 | −33.3195 ± 40.643 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, D.-S.; An, S.-B.; Kim, D.-H.; Huh, J.-B.; Lee, Y.-J. Comparison of Cutting Efficiency Between Natural and Synthetic Diamond-Coated Burs on Zirconia and Natural Teeth. Materials 2025, 18, 5623. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245623

Kim D-S, An S-B, Kim D-H, Huh J-B, Lee Y-J. Comparison of Cutting Efficiency Between Natural and Synthetic Diamond-Coated Burs on Zirconia and Natural Teeth. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5623. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245623

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Da-Sol, Sung-Bin An, Da-Hae Kim, Jung-Bo Huh, and You-Jin Lee. 2025. "Comparison of Cutting Efficiency Between Natural and Synthetic Diamond-Coated Burs on Zirconia and Natural Teeth" Materials 18, no. 24: 5623. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245623

APA StyleKim, D.-S., An, S.-B., Kim, D.-H., Huh, J.-B., & Lee, Y.-J. (2025). Comparison of Cutting Efficiency Between Natural and Synthetic Diamond-Coated Burs on Zirconia and Natural Teeth. Materials, 18(24), 5623. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245623