Effect of Mo2C Addition on Microstructure and Wear Behavior of HVOF Carbide-Metal Composite Coatings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Preparation of Mo2C-Containing Feedstock Powders

2.2. HVOF Sprayed Coating

2.3. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

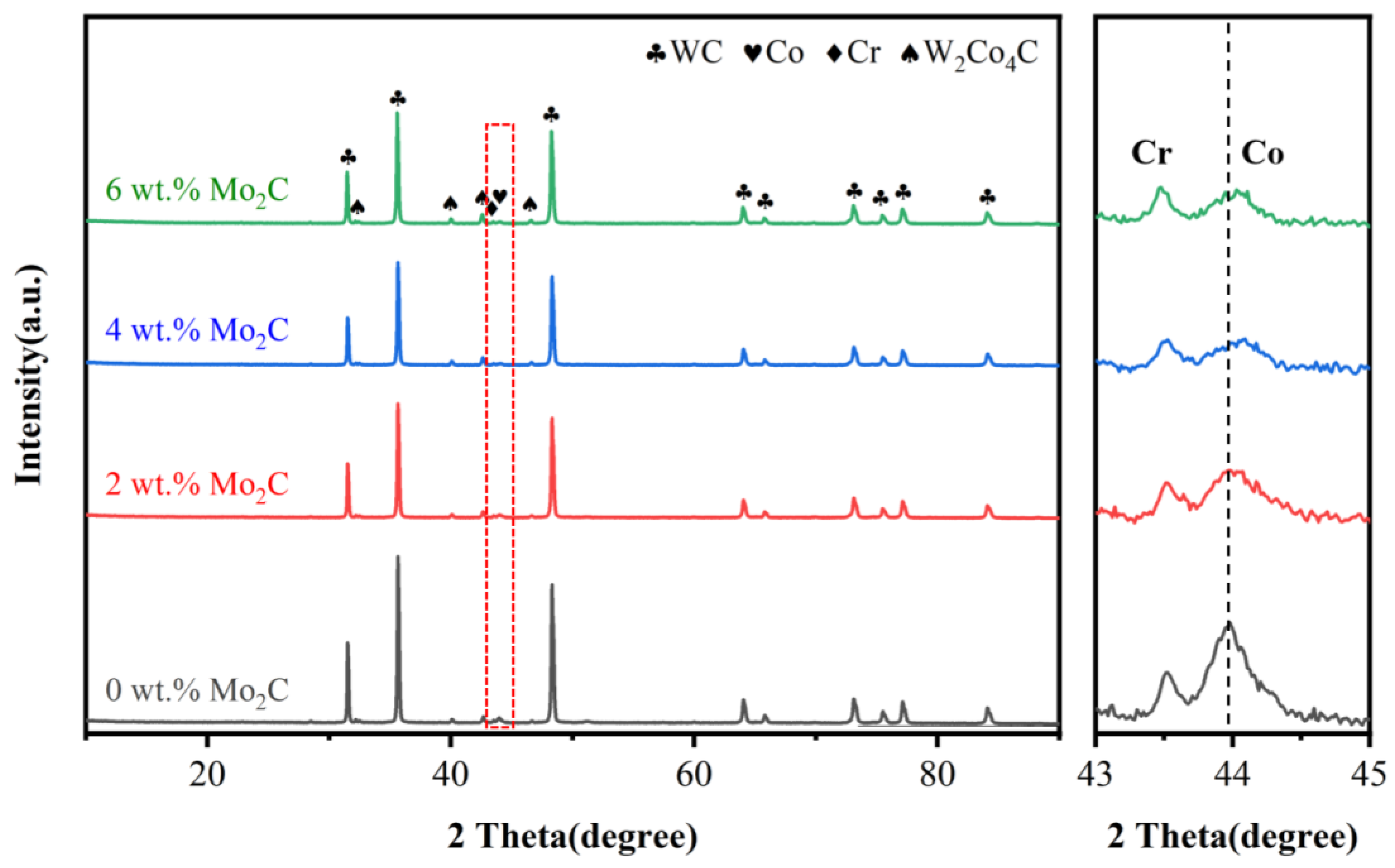

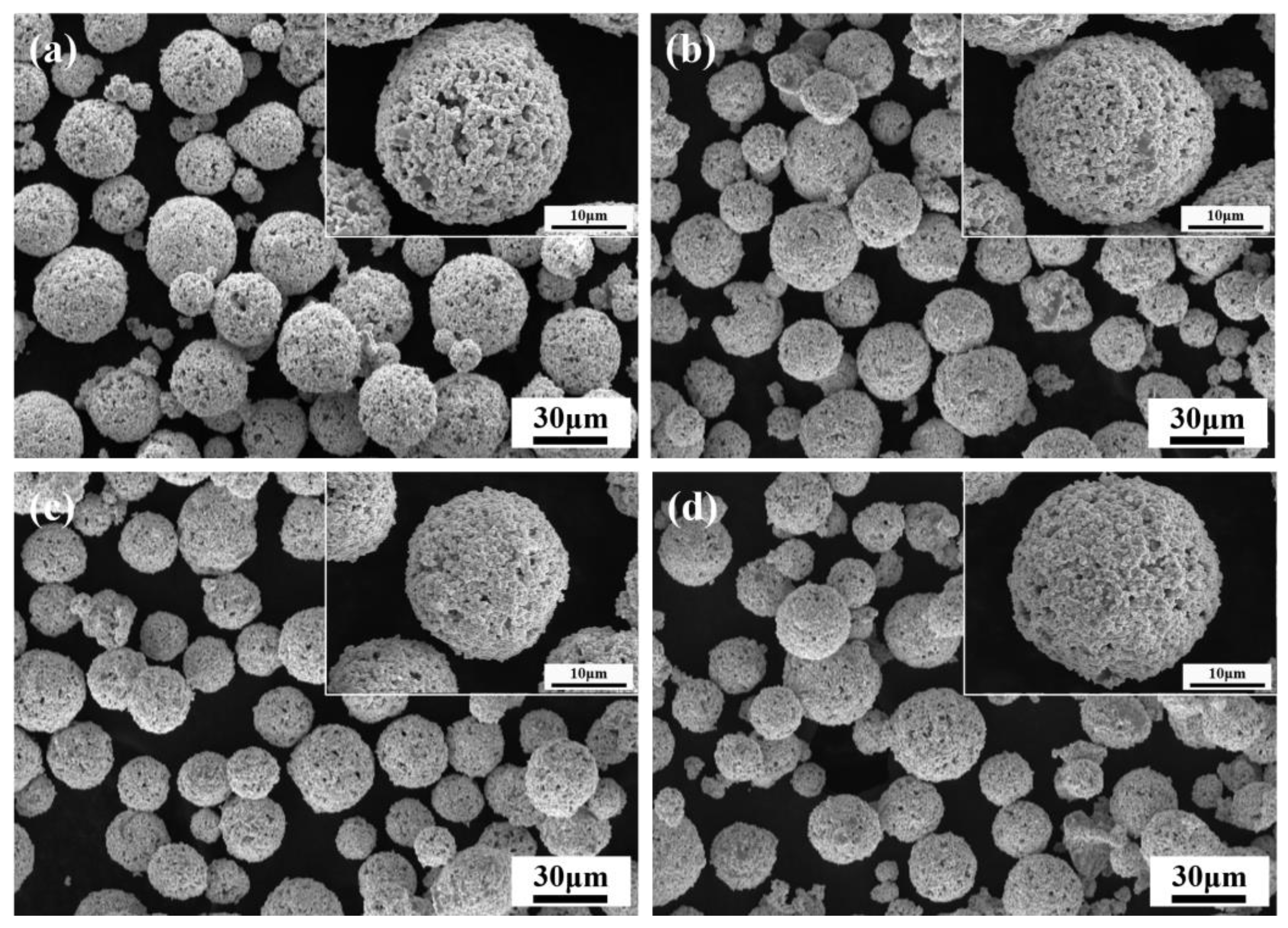

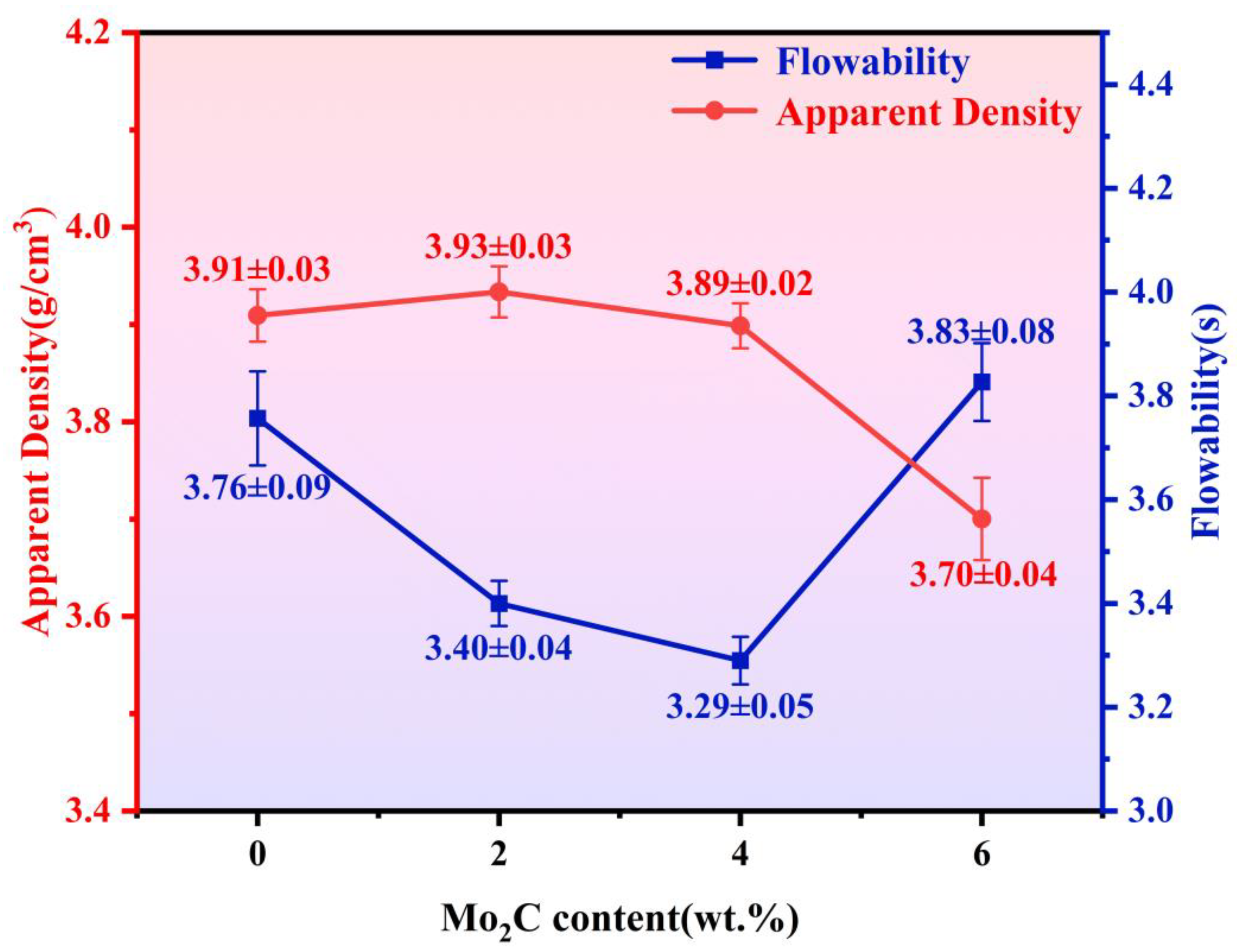

3.1. Characterization of Feedstock Powder

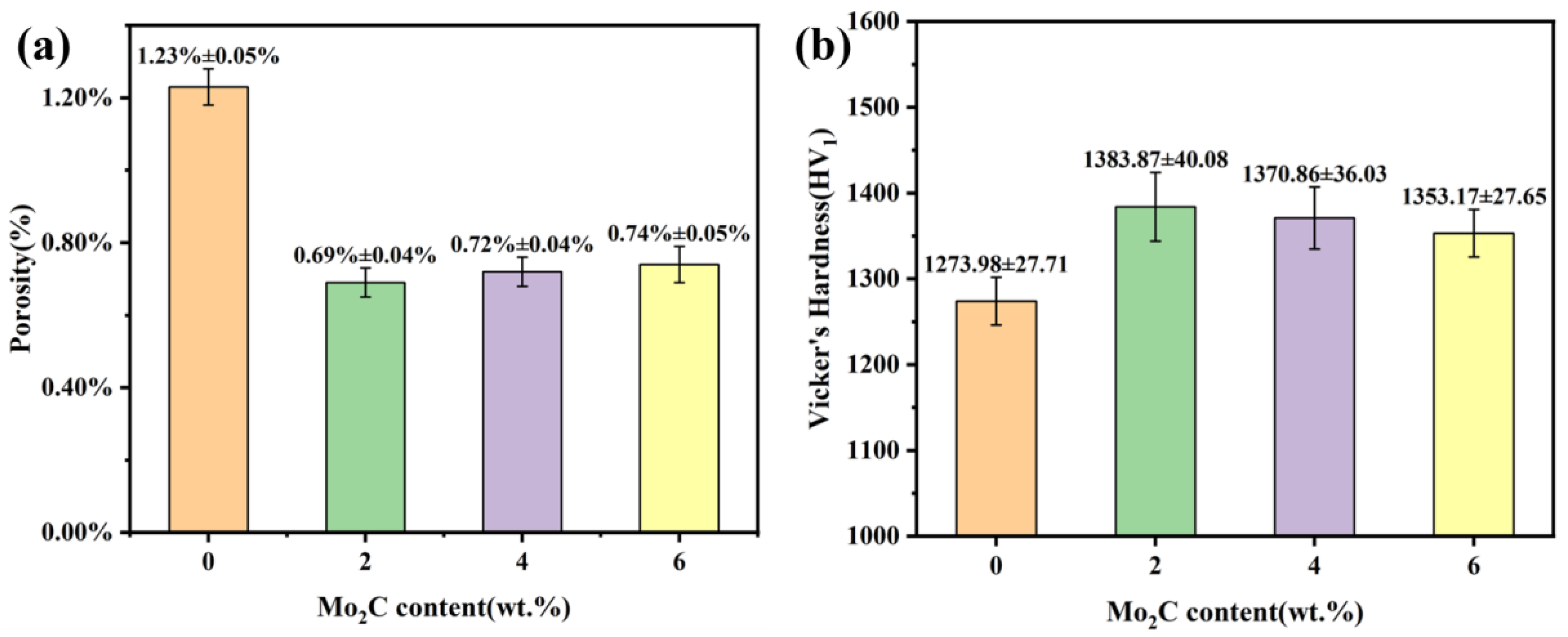

3.2. Microstructures and Properties of HVOF Coating

3.3. Wear Behavior of the HVOF Coatings

3.3.1. At Room Temperature

3.3.2. At 400 °C

3.3.3. Wear Mechanism

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mozetič, M. Surface Modification to Improve Properties of Materials. Materials 2019, 12, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huczko, A.; Dąbrowska, A.; Savchyn, V.; Popov, A.I.; Karbovnyk, I. Silicon carbide nanowires: Synthesis and cathodoluminescence. Phys. Status Solidi B 2009, 246, 2806–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, A.S.; Suzdal’tsev, A.V.; Anfilogov, V.N.; Farlenkov, A.S.; Porotnikova, N.M.; Vovkotrub, E.G.; Akashev, L.A. Carbothermal Synthesis, Properties, and Structure of Ultrafine SiC Fibers. Inorg. Mater. 2020, 56, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uglov, V.V.; Kholad, V.M.; Grinchuk, P.S.; Ivanov, I.A.; Kozlovsky, A.L.; Zdorovets, M.V. Study of the Microstructure and Phase Composition of Ceramics Based on Silicon Carbide Irradiated with Low-Energy Helium Ions. Inorg. Mater. Appl. Res. 2024, 15, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.; Yunhe, Z.; Jian, W.; Yong, T.; Jie, S. Study on the Interaction between Corrosion and Sliding Wear of Thermal Spraying WC-10Co4Cr Coating. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2025, 34, 1269–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolelli, G.; Berger, L.M.; Börner, T.; Koivuluoto, H.; Lusvarghi, L.; Lyphout, C.; Markocsan, N.; Matikainen, V.; Nylén, P.; Sassatelli, P.; et al. Tribology of HVOF- and HVAF-sprayed WC-10Co4Cr hardmetal coatings: A comparative assessment. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 265, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkashvand, K.; Selpol, V.K.; Gupta, M.; Joshi, S. Influence of Test Conditions on Sliding Wear Performance of High Velocity Air Fuel-Sprayed WC-CoCr Coatings. Materials 2021, 14, 3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Guo, Z.; Xiong, J.; Lei, Y.; Li, Y.; Tang, J.; Liu, J.; Ye, J. Corrosion behavior of HVOF sprayed hard face coatings in alkaline-sulfide solution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 416, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkashvand, K.; Gupta, M.; Björklund, S.; Marra, F.; Baiamonte, L.; Joshi, S. Influence of nozzle configuration and particle size on characteristics and sliding wear behaviour of HVAF-sprayed WC-CoCr coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 423, 127585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subba Rao, M.; Ramesh, M.R.; Ravikiran, K. Solid Particle Erosion Behavior of Partially Oxidized Al with NiCr Composite Coating at Elevated Temperature. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 30, 3749–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, A.A.; Dubey, A.K. Recent trends in laser cladding and surface alloying. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 134, 106619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.; Jiang, W.; Luzin, V.; Gong, T.; Feng, W.; Ruiz-Hervias, J.; Yao, P. Influence of WC Particle Size on the Mechanical Properties and Residual Stress of HVOF Thermally Sprayed WC-10Co-4Cr Coatings. Materials 2022, 15, 5537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Guo, Z.; Li, S.; Xiao, Y.; Chai, B.; Liu, J. Microstructure and properties of WC-17Co cermets prepared using different processing routes. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 9203–9210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Ge, Y.; Kong, D. Microstructure, dry sliding friction performances and wear mechanism of laser cladded WC-10Co4Cr coating with different Al2O3 mass fractions. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 406, 126749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, X.; Dejun, K. Microstructure and tribological properties of laser cladded TiC reinforced WC-10Co4Cr coatings at 500 °C. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 40, 109548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Guo, Z.; Shen, B.; Cao, D. The effect of WC, Mo2C, TaC content on the microstructure and properties of ultra-fine TiC0.7N0.3 cermet. Mater. Des. 2007, 28, 1689–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Xiong, J.; Yang, M.; Wang, J.; Sun, L.; Wu, Y.; Chen, J.; Xiong, S. Microstructure and properties of Ti(C,N)-Mo2C-Fe cermets. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2009, 27, 781–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Liu, H.; Li, S.; Gao, G.; Hassani, M.; Kou, Z. Effect of Ni, W and Mo on the microstructure, phases and high-temperature sliding wear performance of CoCr matrix alloys. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2020, 21, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behera, N.; Ramesh, M.R.; Rahman, M.R. Elevated temperature wear and friction performance of WC-CoCr/Mo and WC-Co/NiCr/Mo coated Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Mater. Charact. 2024, 215, 114207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Xiong, J.; Yang, M.; Song, X.; Jiang, C. Effect of Mo2C on the microstructure and properties of WC–TiC–Ni cemented carbide. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2008, 26, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.-C.; Lan, X.; Wang, Y.-L.; Zhang, G.-H. Effect of Mo2C on the microstructure and properties of (W,Mo)C-10Co cemented carbides. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2023, 111, 106103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K. The Co-Cr-Mo (Cobalt-Chromium-Molybdenum) System. J. Phase Equilib. Diffus. 2005, 26, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.-K.; Yeh, J.-W. Inhibition of grain coarsening up to 1000 °C in (AlCrNbSiTiV)N superhard coatings. Scr. Mater. 2010, 62, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, K.; Guo, Z.; Hua, T.; Xiong, J.; Liao, J.; Liang, L.; Yang, S.; Yi, J.; Zhang, H. Strengthening mechanism of cemented carbide containing Re. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 838, 142803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Yan, W.; Yi, J.; Wang, S.; Huang, X.; Yang, S.; Zhang, M.; Ye, Y. The optimization of mechanical property and corrosion resistance of WC-6Co cemented carbide by Mo2C content. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 17243–17251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Li, X.; Pan, C.; Fan, J. Effect of Mo2C Addition on the Tribological Behavior of Ti(C,N)-Based Cermets. Materials 2023, 16, 5645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genga, R.M.; Cornish, L.A.; Akdogan, G. Effect of Mo2C additions on the properties of SPS manufactured WC-TiC-Ni cemented carbides. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2013, 41, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.I.; Lee, K.H.; Ryu, H.J.; Hong, S.H. Analytical modeling to calculate the hardness of ultra-fine WC-Co cemented carbides. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 489, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, Z.; Feng, S. Effect of CeO2 on Impact Toughness and Corrosion Resistance of WC Reinforced Al-Based Coating by Laser Cladding. Materials 2019, 12, 2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Li, Q.; He, P.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, J.; Cheng, J. Microstructure and properties of plasma-sprayed AlCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy coatings via CeO2 doping. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 38, 4351–4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantetti, A.; Tamatam, L.R.; Volvert, M.; Lawal, I.; Liu, L.; Salles, L.; Brake, M.R.W.; Schwingshackl, C.W.; Nowell, D. The impact of fretting wear on structural dynamics: Experiment and Simulation. Tribol. Int. 2019, 138, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motallebzadeh, A.; Atar, E.; Cimenoglu, H. Sliding wear characteristics of molybdenum containing Stellite 12 coating at elevated temperatures. Tribol. Int. 2015, 91, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilawary, S.A.A.; Motallebzadeh, A.; Atar, E.; Cimenoglu, H. Influence of Mo on the high temperature wear performance of NiCrBSi hardfacings. Tribol. Int. 2018, 127, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhai, W.; Dong, H.; Wang, Y.; He, L. Improvement of High Temperature Wear Behavior of In-Situ Cr3C2-20 wt.% Ni Cermet by Adding Mo. Crystals 2020, 10, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashishtha, N.; Sapate, S.G. Abrasive wear maps for High Velocity Oxy Fuel (HVOF) sprayed WC-12Co and Cr3C2−25NiCr coatings. Tribol. Int. 2017, 114, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Liu, R.; Lu, X.; Zhang, S.; Liu, S. Tribological Behavior of Lamellar Molybdenum Trioxide as a Lubricant Additive. Materials 2018, 11, 2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lu, X.; Luo, J. Tribological properties of rare earth oxide added Cr3C2-NiCr coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2007, 253, 4377–4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Number | WC (wt.%) | Co (wt.%) | Cr (wt.%) | Mo2C (wt.%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | Bal | 10 | 4 | 0 |

| C2 | Bal | 10 | 4 | 2 |

| C3 | Bal | 10 | 4 | 4 |

| C4 | Bal | 10 | 4 | 6 |

| Points | Elements (wt.%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | W | Co | Cr | O | Zr | Mo | |

| A | 8.67 | 73.95 | 10.19 | 2.02 | 4.29 | 0.88 | 0 |

| B | 4.78 | 56.53 | 7.81 | 20.67 | 8.11 | 2.10 | 0 |

| C | 6.72 | 70.87 | 11.50 | 1.50 | 6.35 | 3.06 | 0 |

| D | 4.49 | 57.66 | 7.83 | 5.53 | 11.20 | 12.45 | 0.85 |

| E | 6.30 | 33.69 | 6.15 | 2.51 | 21.79 | 28.10 | 1.47 |

| F | 9.18 | 76.73 | 9.31 | 1.24 | 1.72 | 0.82 | 1.00 |

| G | 7.28 | 64.89 | 9.24 | 4.63 | 8.24 | 1.95 | 3.76 |

| H | 5.13 | 73.17 | 9.77 | 2.59 | 2.14 | 0.47 | 6.73 |

| Points | Elements (wt.%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | W | Co | Cr | O | Zr | Mo | |

| A | 4.74 | 13.26 | 4.13 | 1.25 | 11.7 | 64.91 | 0 |

| B | 13.25 | 66.80 | 16.17 | 1.08 | 2.00 | 0.69 | 0 |

| C | 5.01 | 37.04 | 1.94 | 0.64 | 16.23 | 40.14 | 0 |

| D | 4.60 | 54.81 | 21.73 | 5.07 | 9.92 | 2.31 | 1.56 |

| E | 3.90 | 58.59 | 8.22 | 3.31 | 16.67 | 8.36 | 0.96 |

| F | 5.89 | 50.38 | 9.37 | 4.07 | 18.87 | 9.87 | 1.55 |

| G | 7.40 | 10.43 | 2.55 | 0.98 | 21.44 | 57.19 | 0 |

| H | 5.79 | 24.86 | 3.86 | 0.91 | 15.01 | 49.15 | 0.42 |

| I | 6.14 | 69.18 | 7.48 | 1.99 | 6.07 | 7.68 | 1.47 |

| J | 6.01 | 34.53 | 4.89 | 3.07 | 15.34 | 34.07 | 2.10 |

| K | 7.87 | 13.44 | 3.03 | 1.13 | 21.18 | 53.10 | 0.26 |

| L | 5.13 | 52.70 | 4.04 | 2.25 | 11.42 | 18.58 | 5.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, F.; Xia, X.; Wang, W.; Gong, X.; Yuan, X.; Tang, C.; Lou, X.; Guo, Z.; Wang, L.; Wu, B.; et al. Effect of Mo2C Addition on Microstructure and Wear Behavior of HVOF Carbide-Metal Composite Coatings. Materials 2025, 18, 5622. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245622

Chen F, Xia X, Wang W, Gong X, Yuan X, Tang C, Lou X, Guo Z, Wang L, Wu B, et al. Effect of Mo2C Addition on Microstructure and Wear Behavior of HVOF Carbide-Metal Composite Coatings. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5622. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245622

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Feichi, Xiang Xia, Wei Wang, Xiufang Gong, Xiaohu Yuan, Chunmei Tang, Xia Lou, Zhixing Guo, Longgang Wang, Bin Wu, and et al. 2025. "Effect of Mo2C Addition on Microstructure and Wear Behavior of HVOF Carbide-Metal Composite Coatings" Materials 18, no. 24: 5622. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245622

APA StyleChen, F., Xia, X., Wang, W., Gong, X., Yuan, X., Tang, C., Lou, X., Guo, Z., Wang, L., Wu, B., Zhu, Y., & Yang, M. (2025). Effect of Mo2C Addition on Microstructure and Wear Behavior of HVOF Carbide-Metal Composite Coatings. Materials, 18(24), 5622. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245622