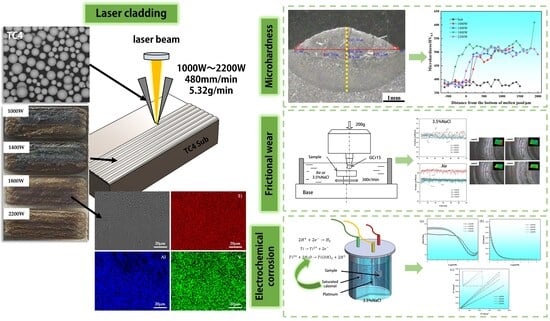

Effect of Laser Power on the Corrosion and Wear Resistance of Laser Cladding TC4 Alloy

Abstract

1. Introduction

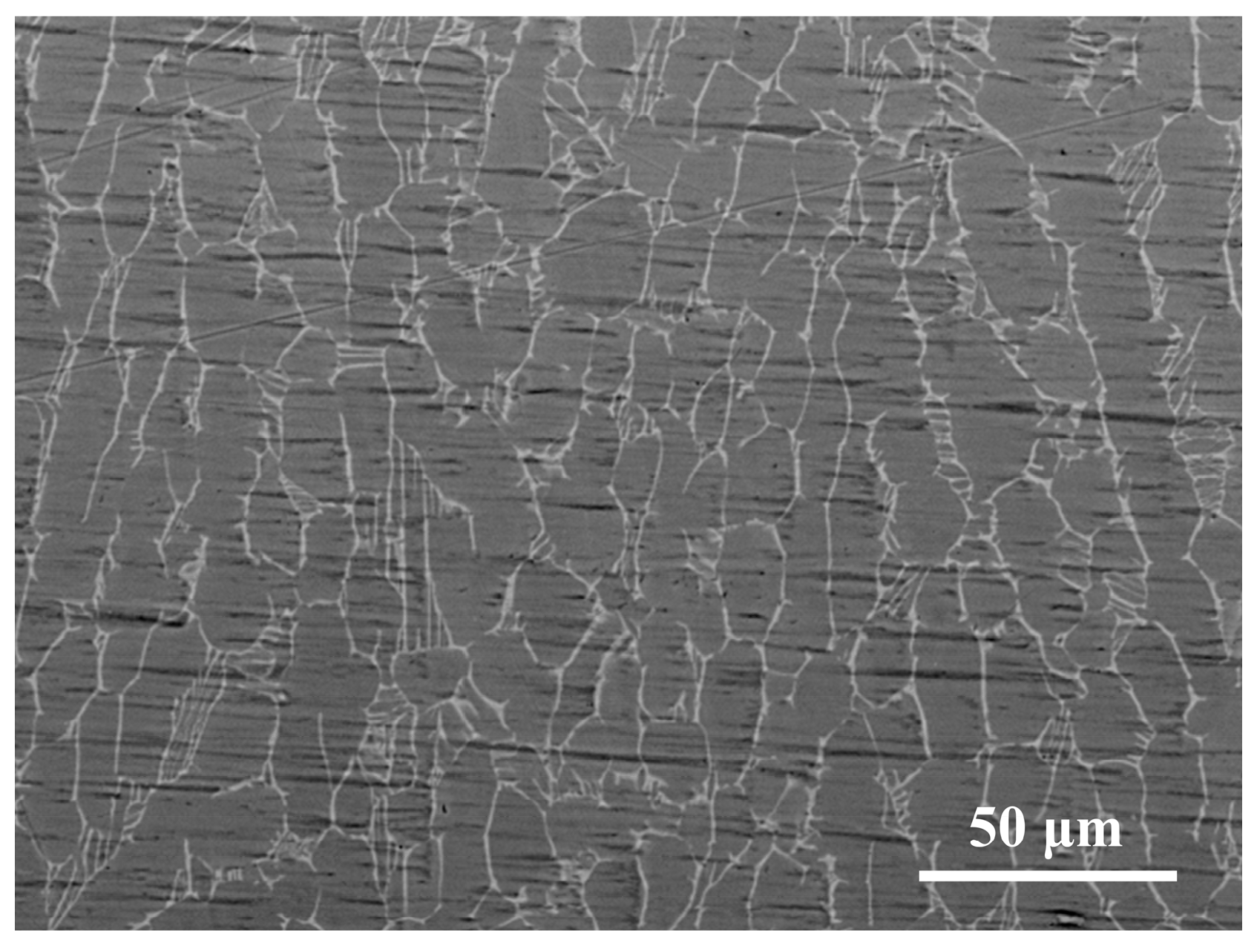

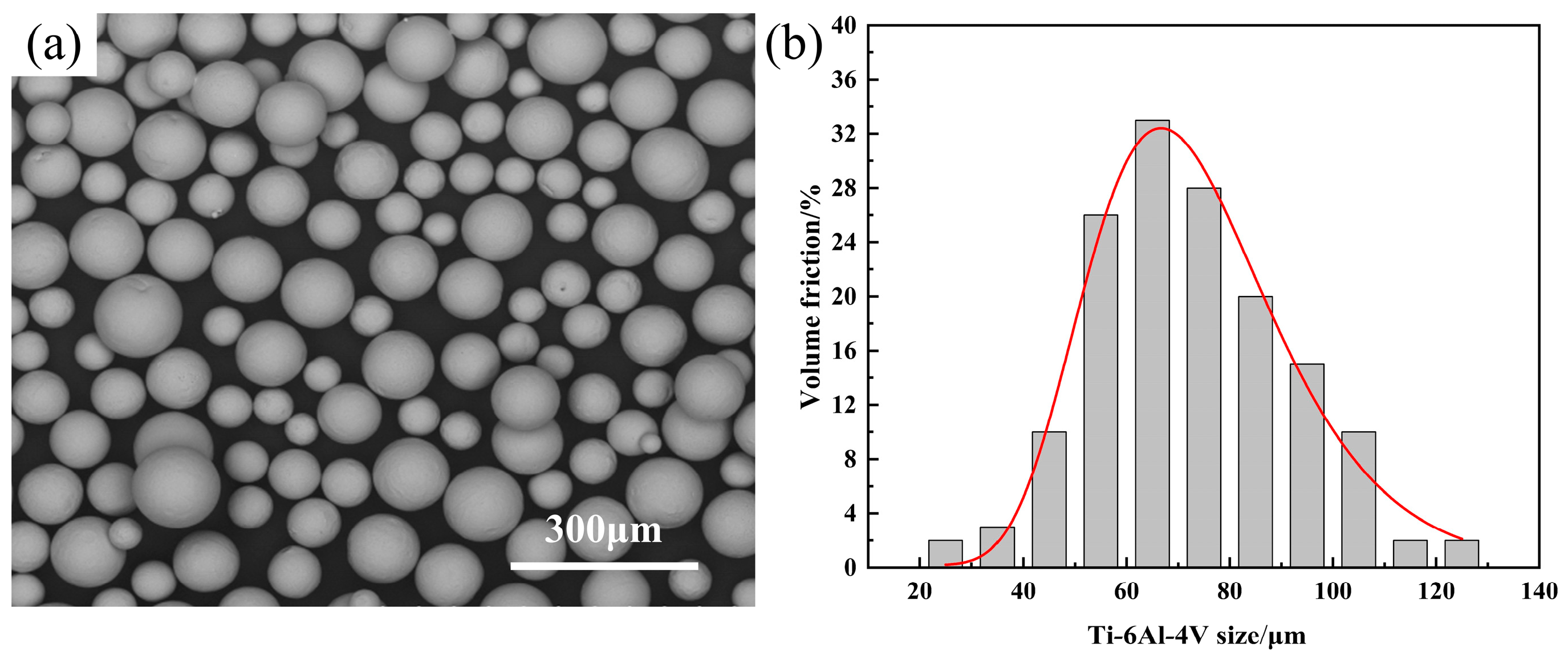

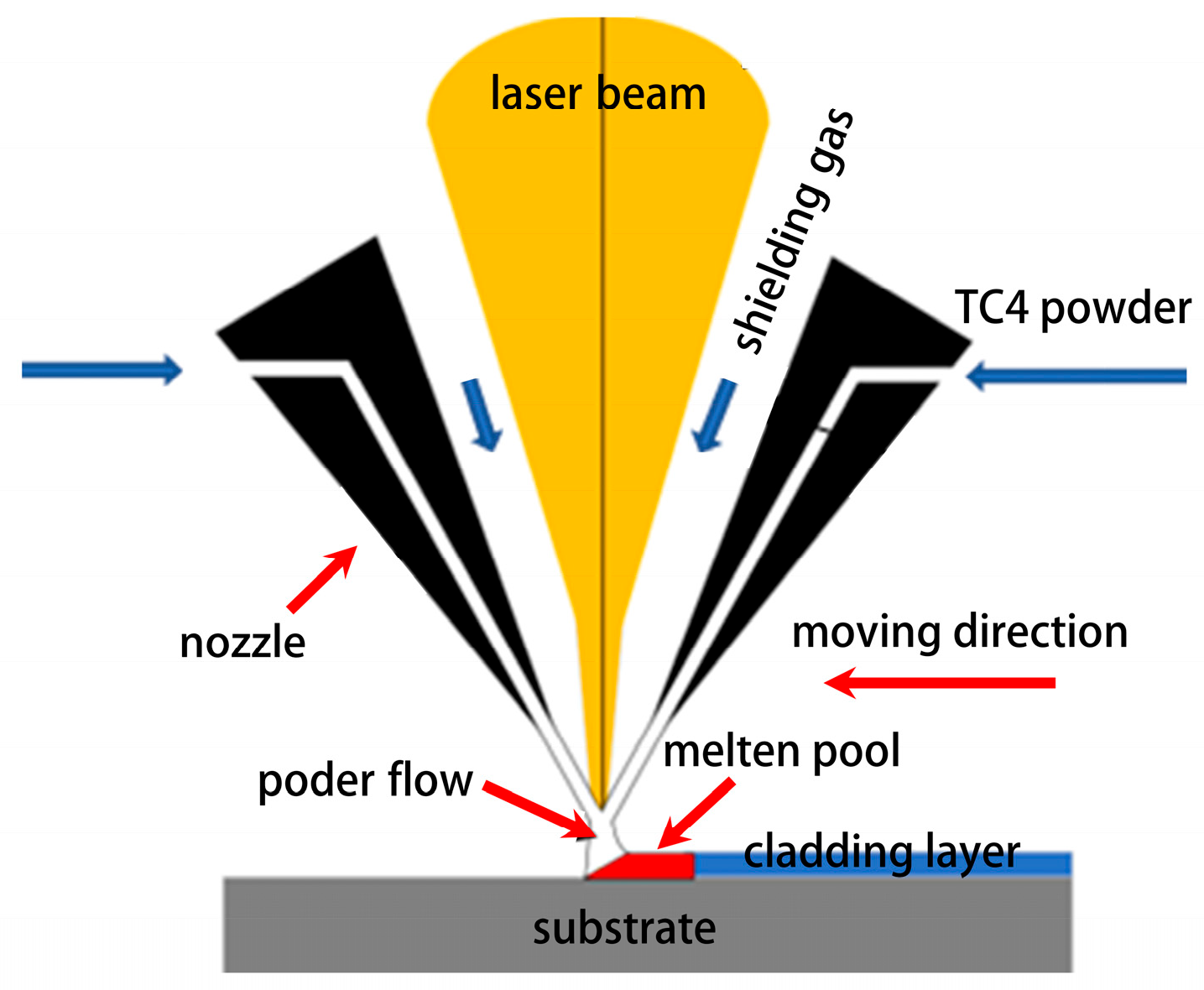

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. Experimental Materials and Equipment

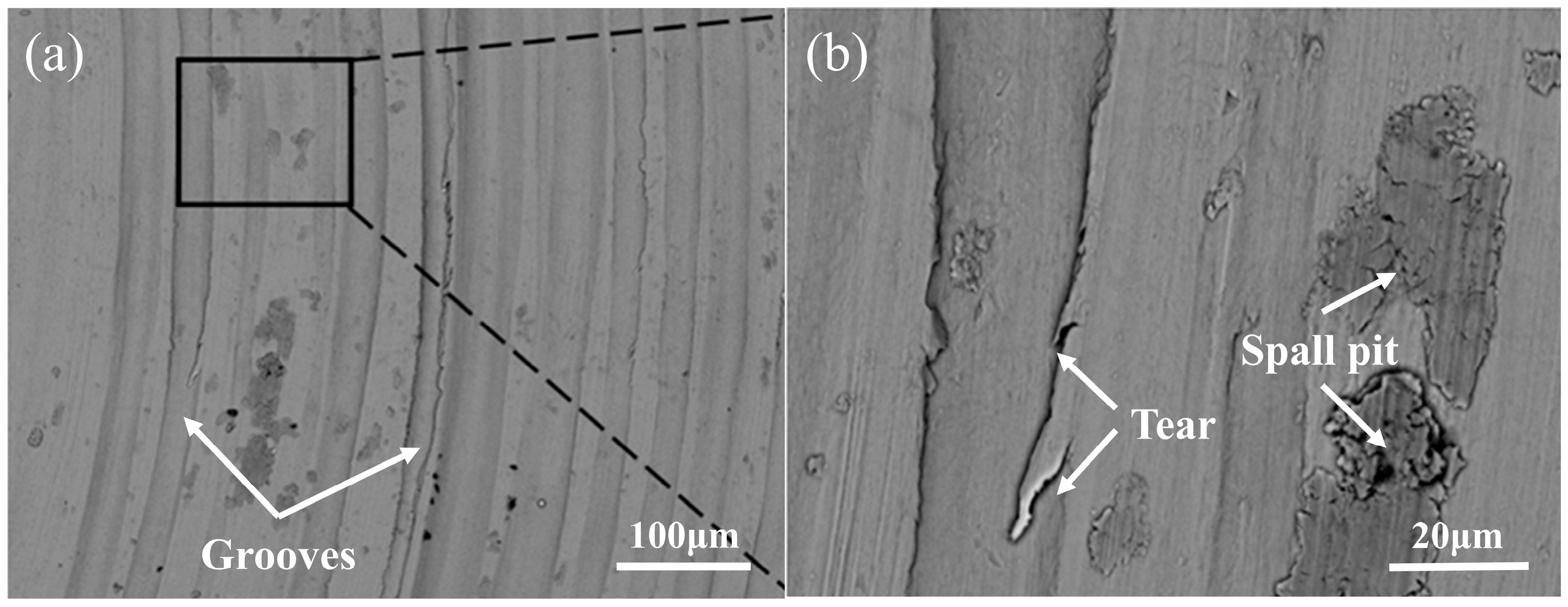

2.2. Performance Testing

3. Results and Discussion

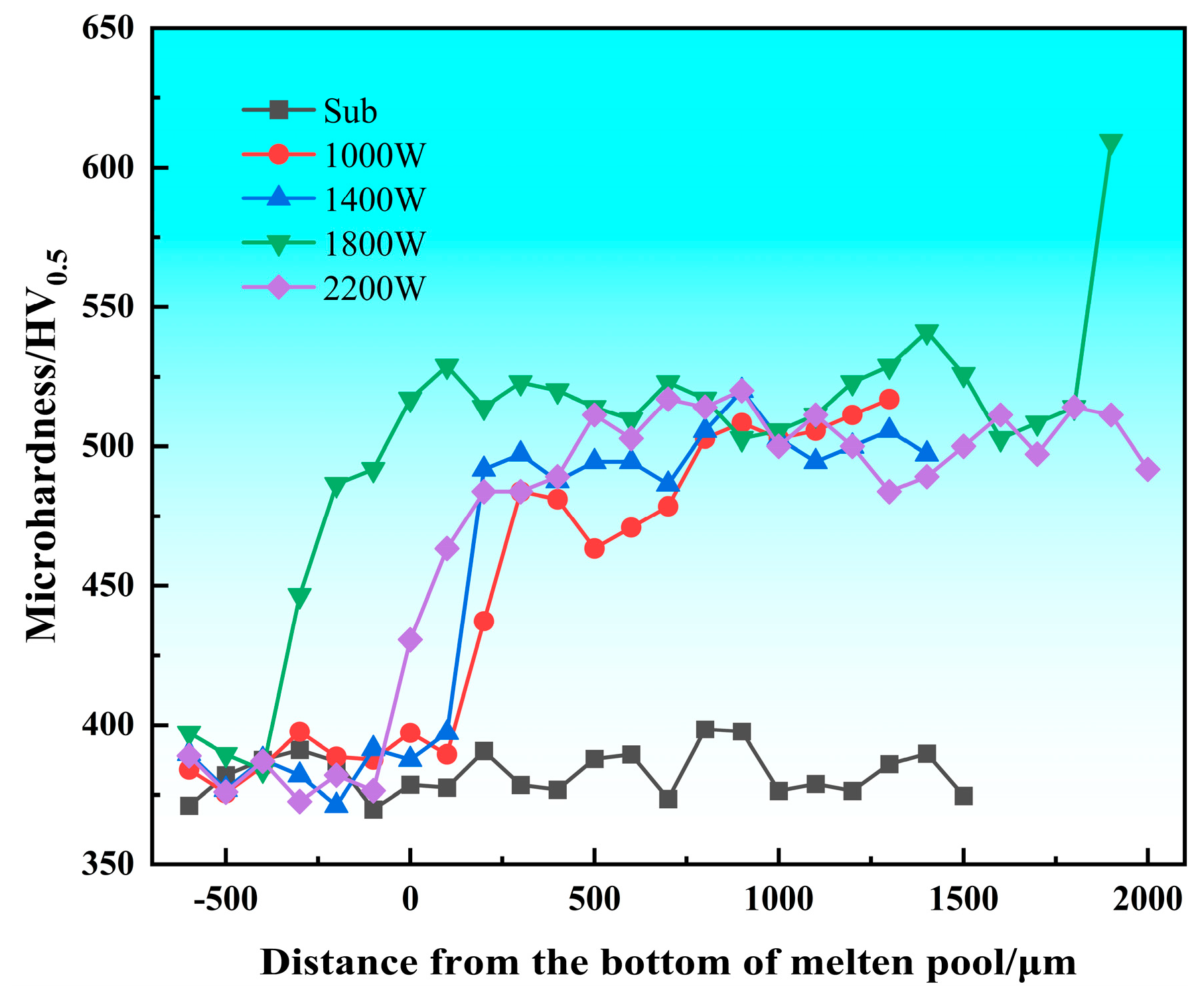

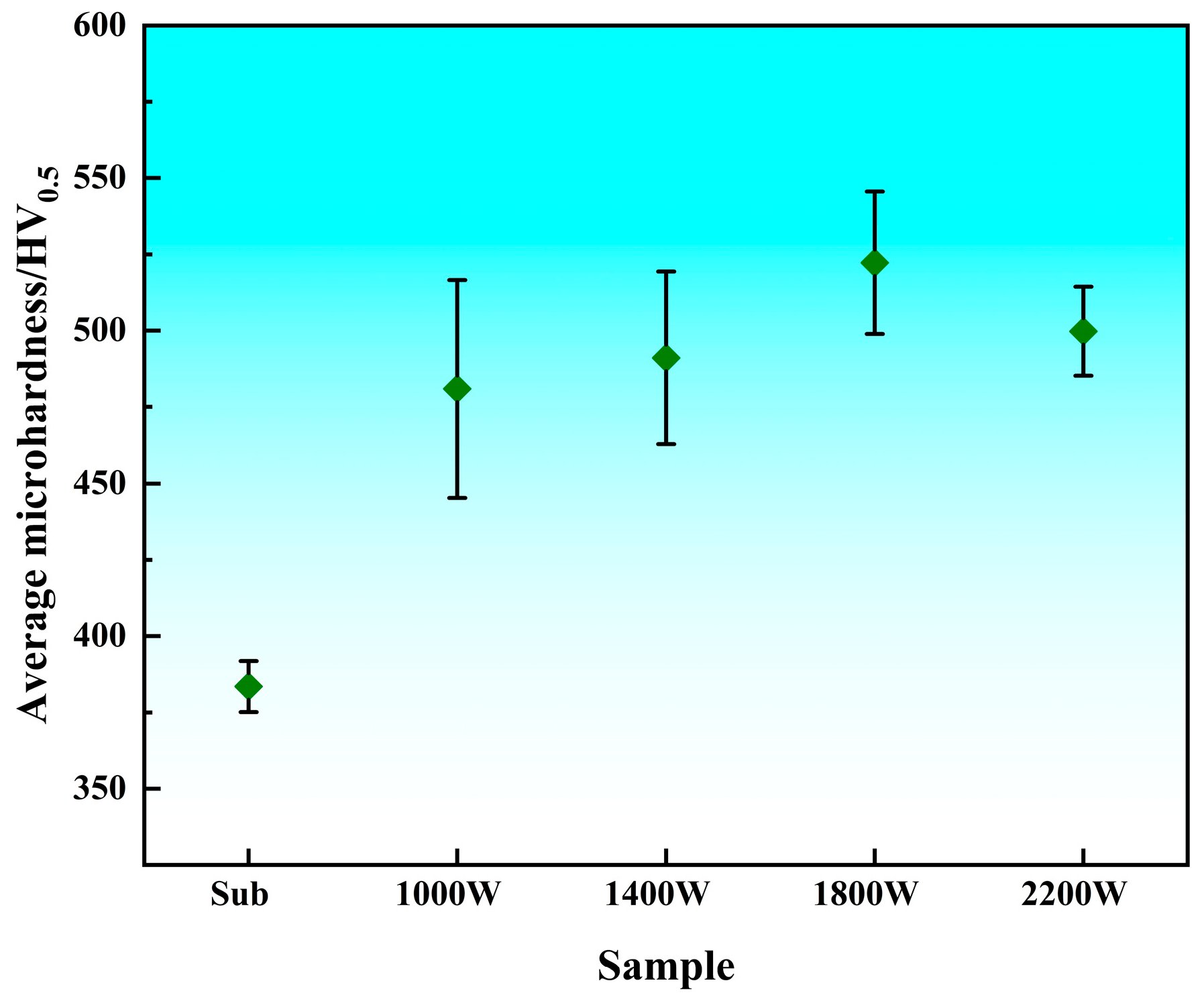

3.1. Microhardness Analysis

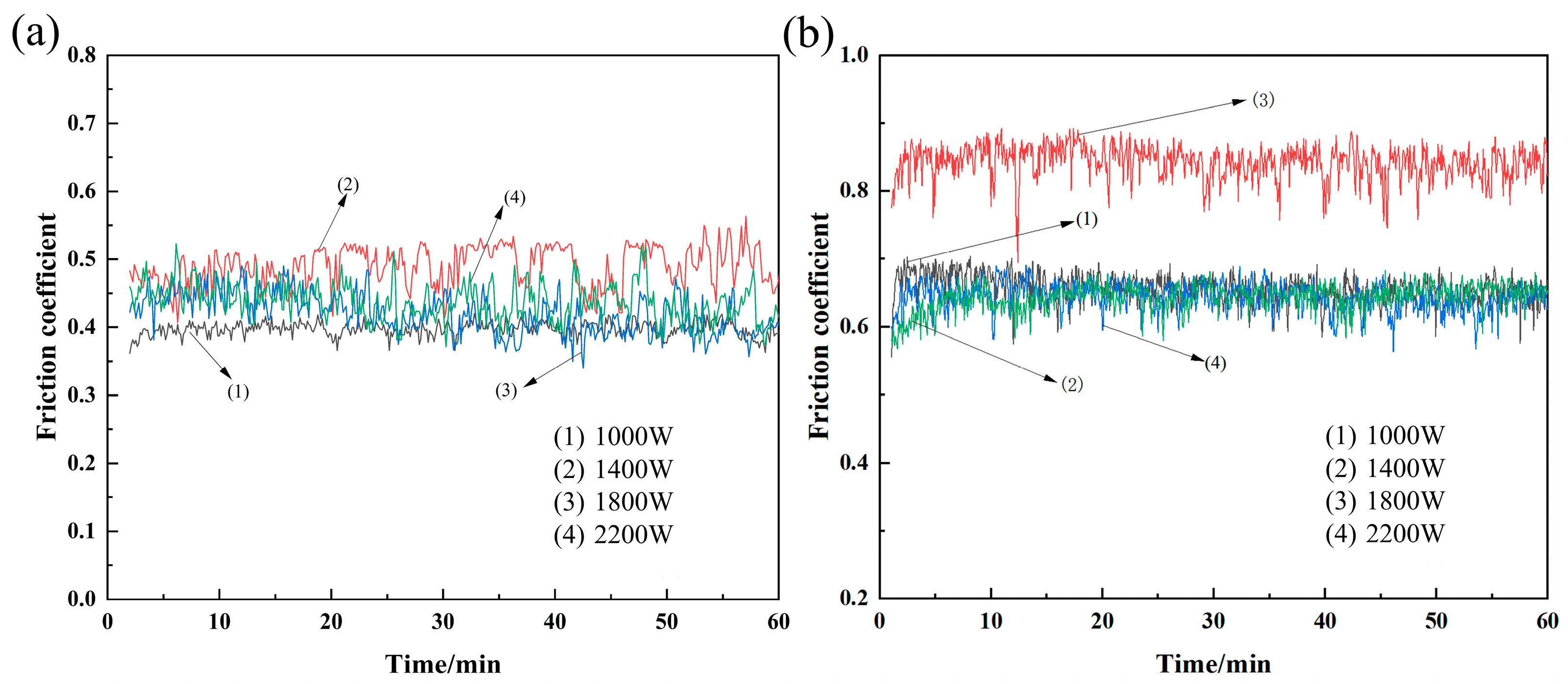

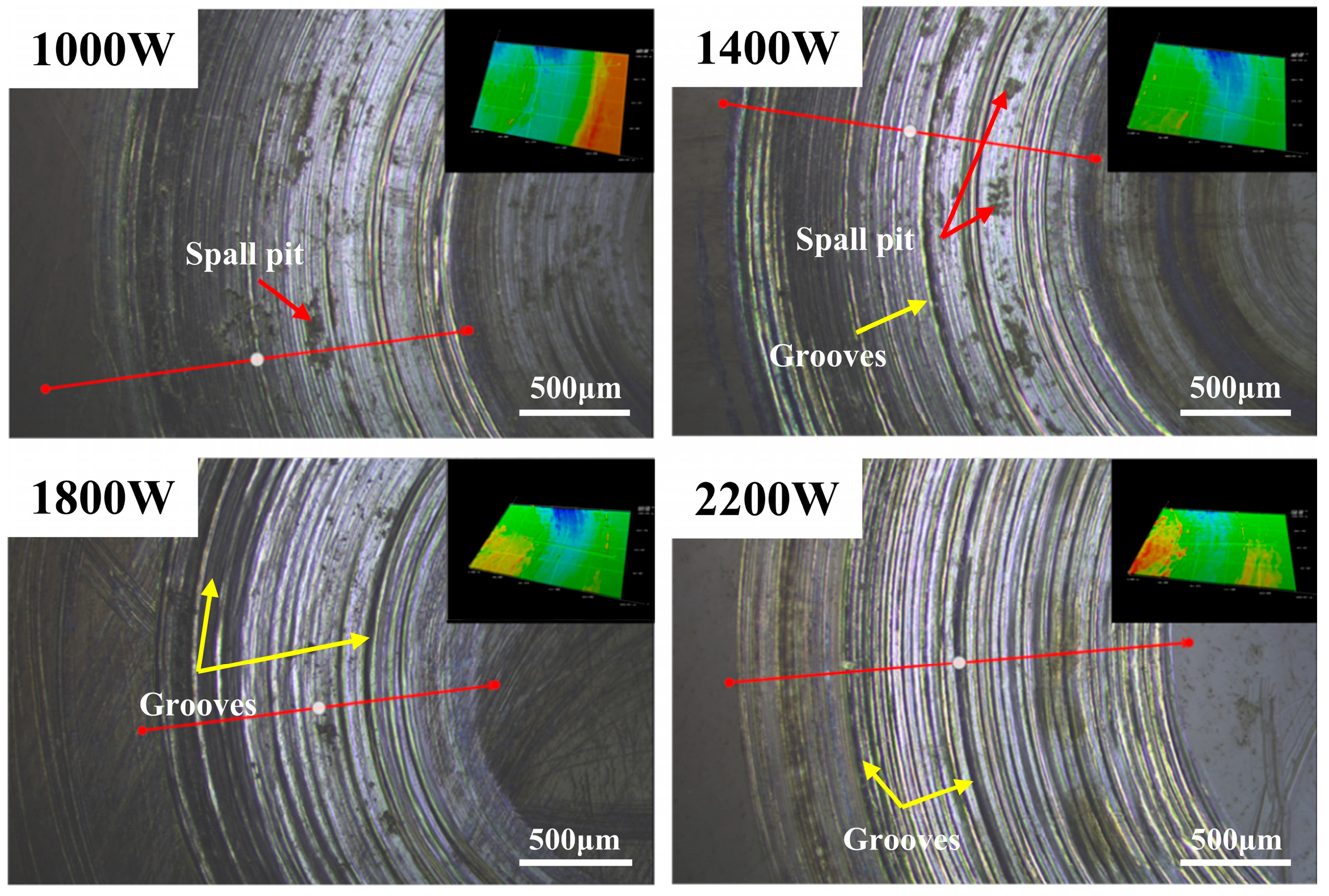

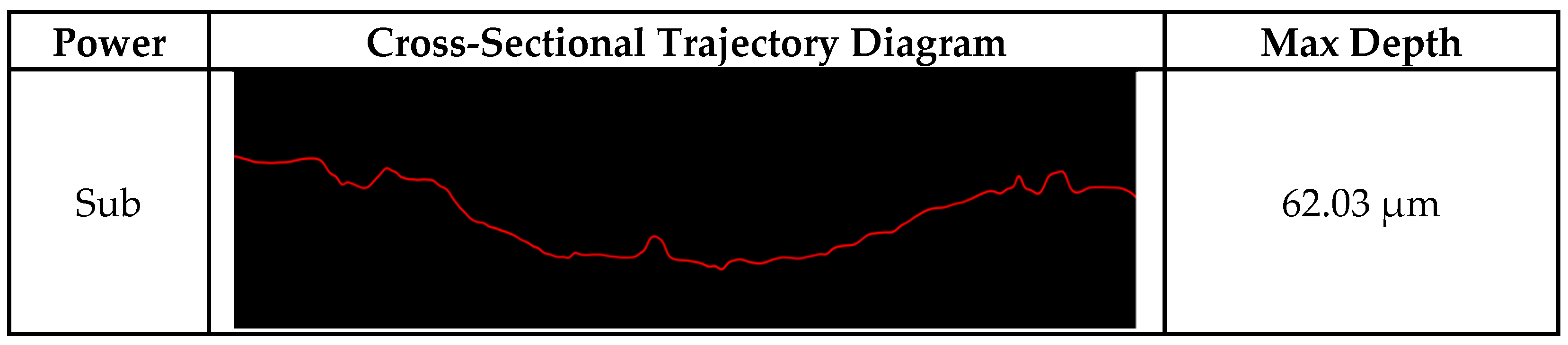

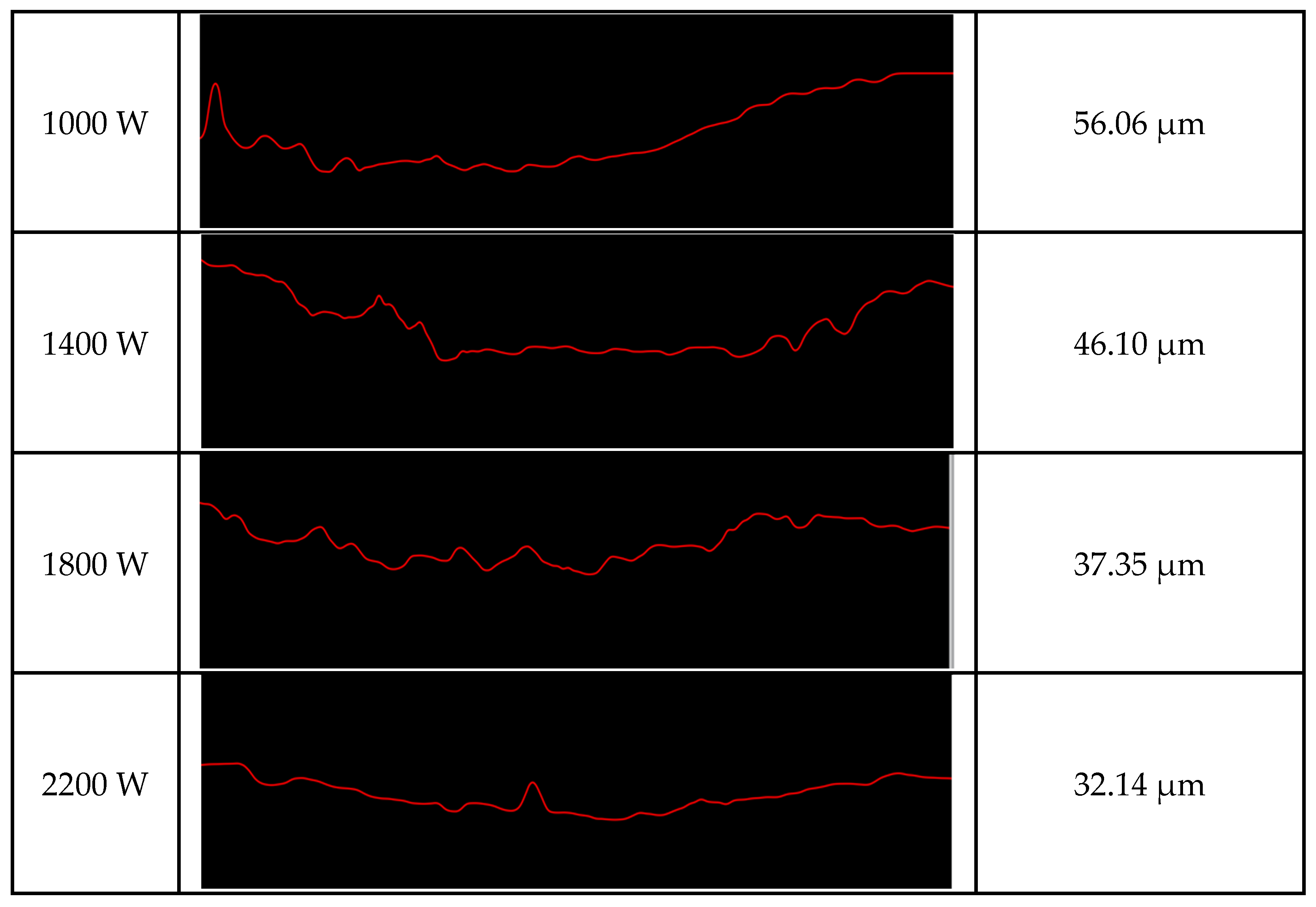

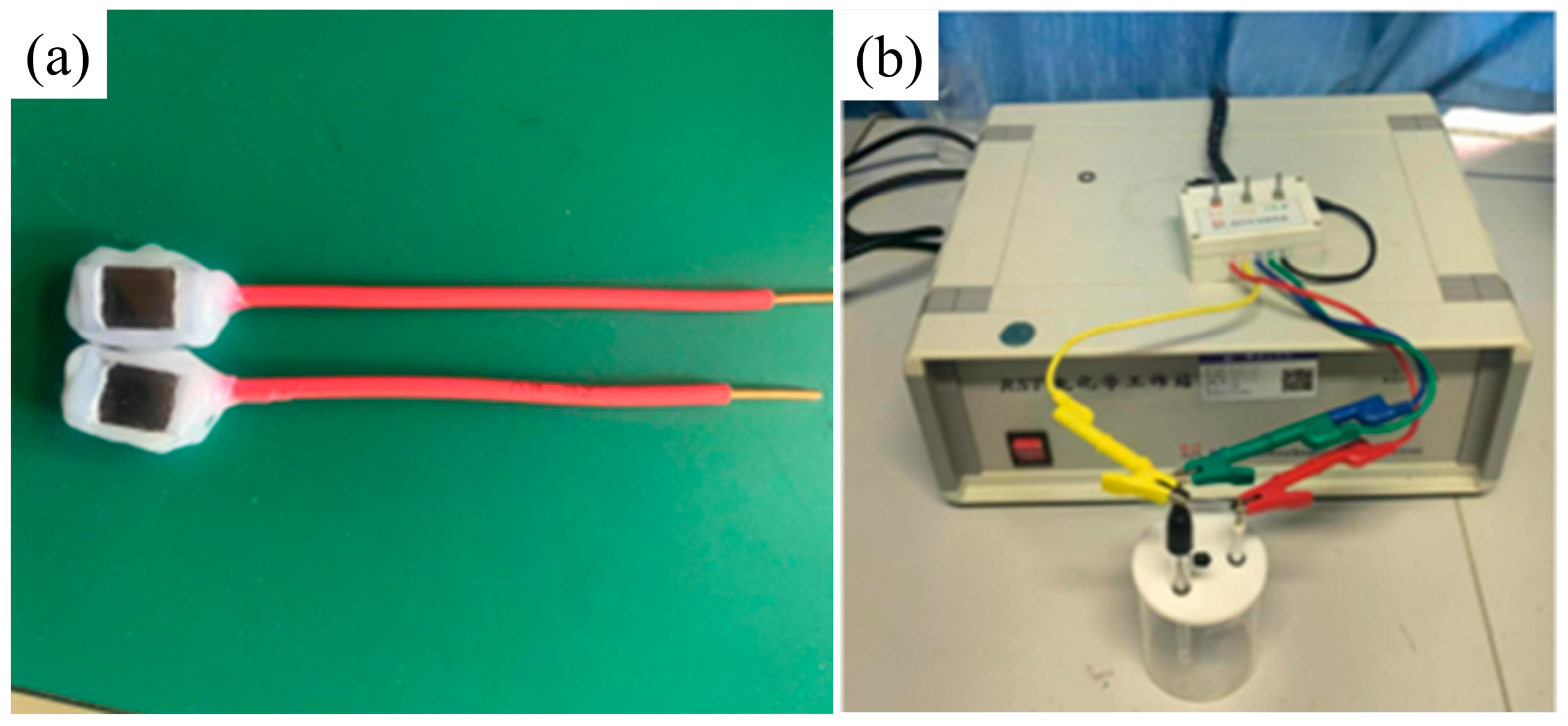

3.2. Cladding Layer Friction and Wear Experiment

3.3. Electrochemical Corrosion Behavior of Cladding Layers

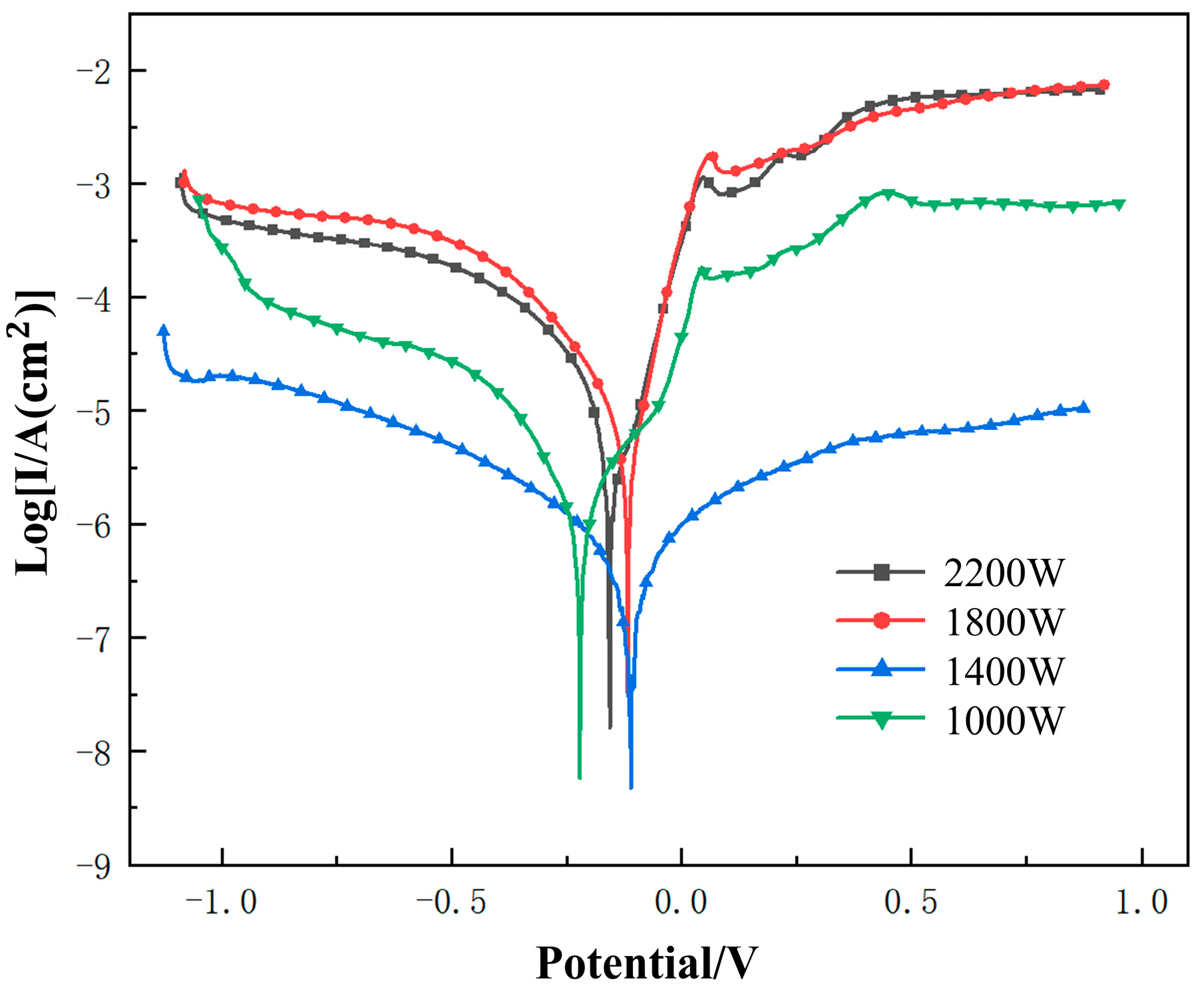

3.3.1. Potentiodynamic Polarization Curve

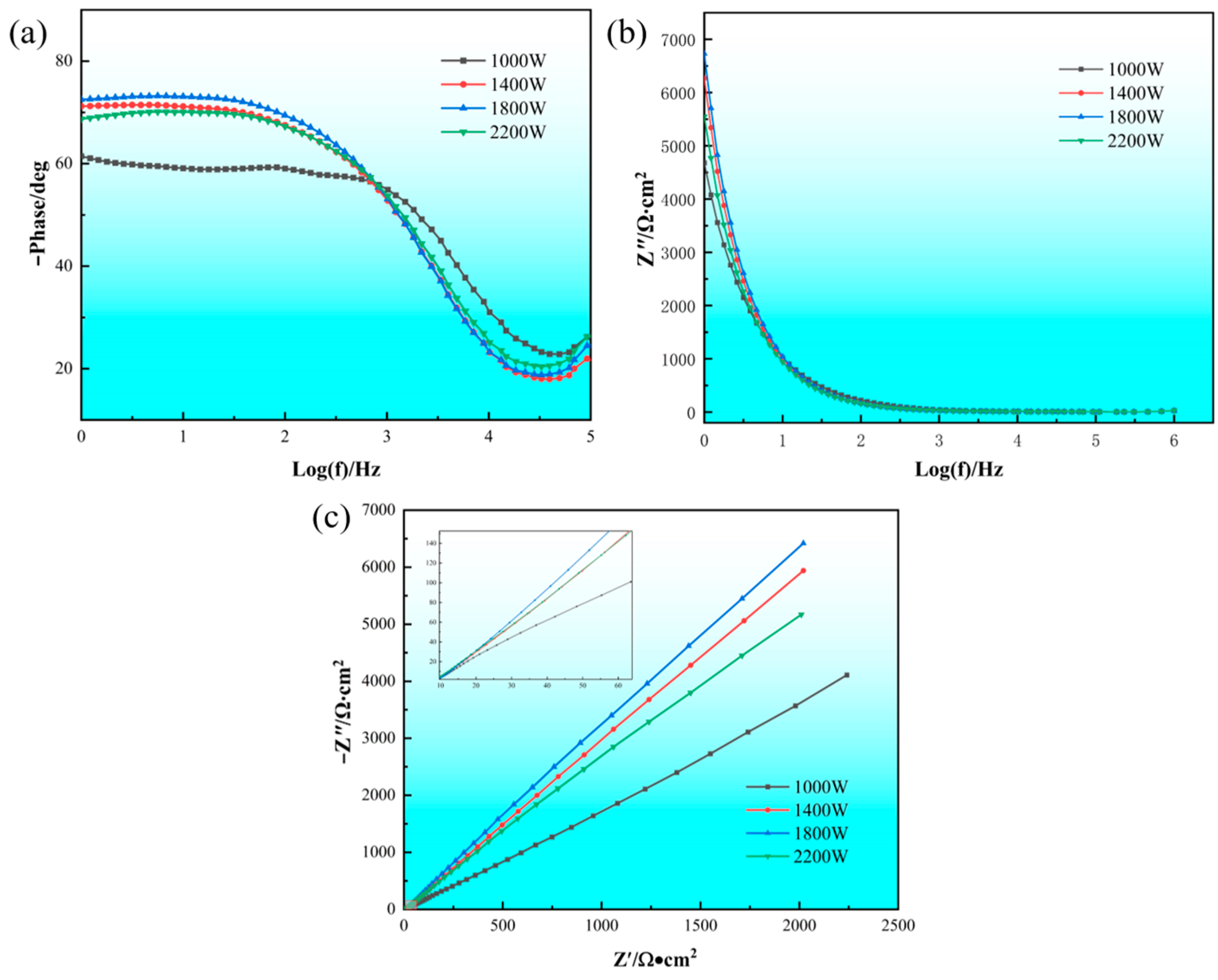

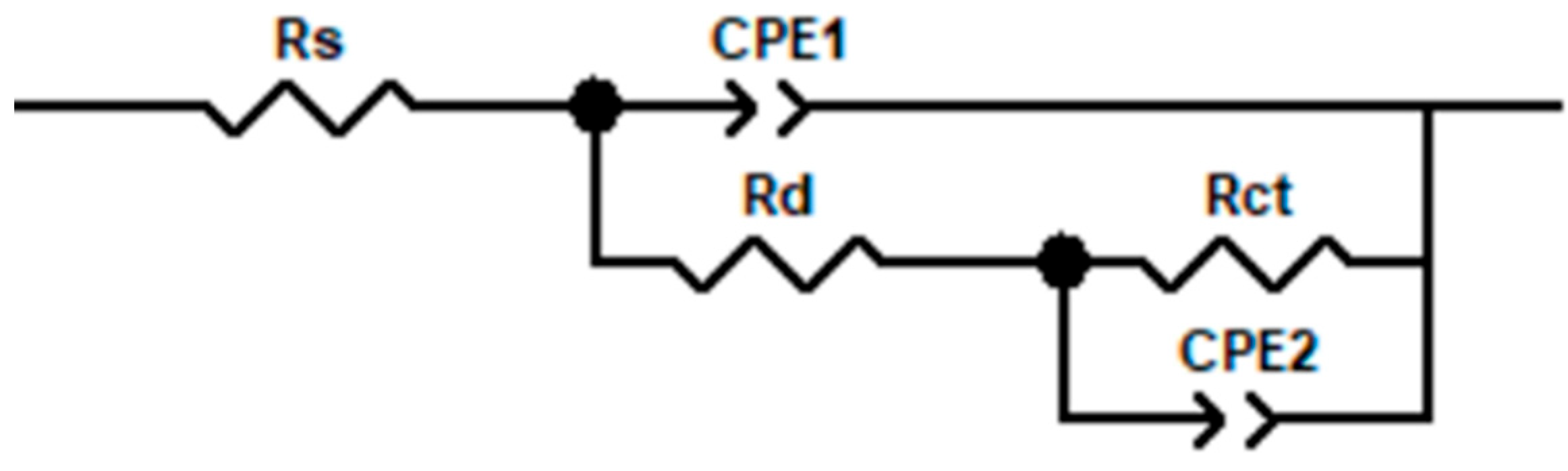

3.3.2. AC Impedance Spectroscopy

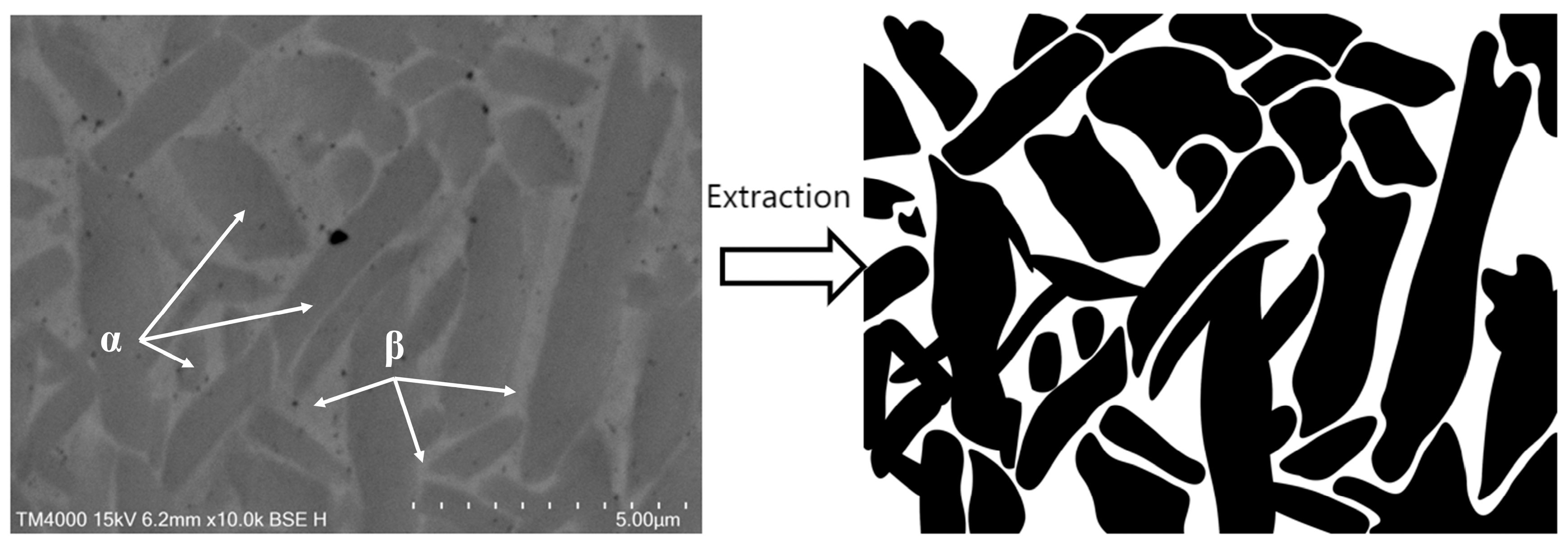

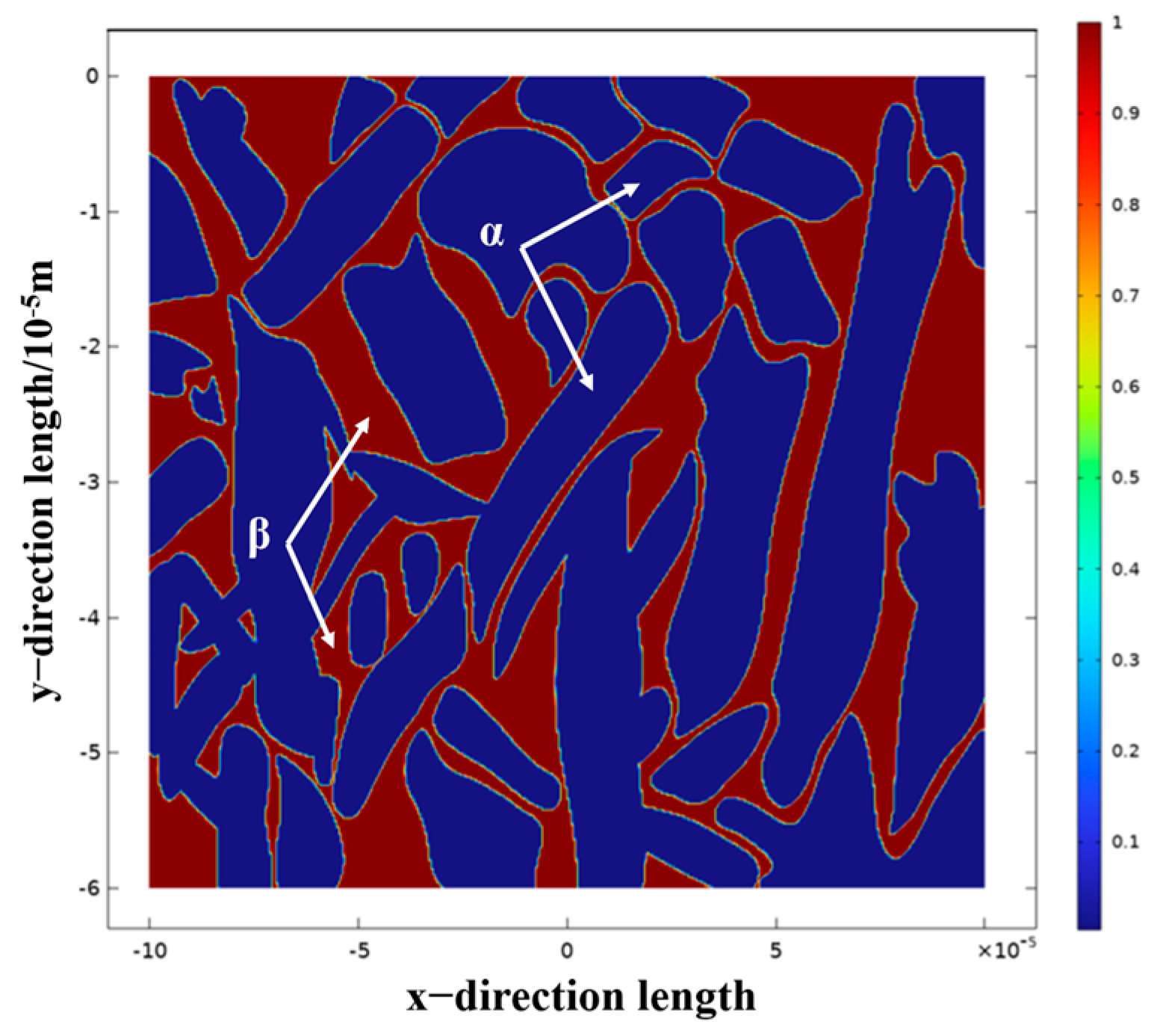

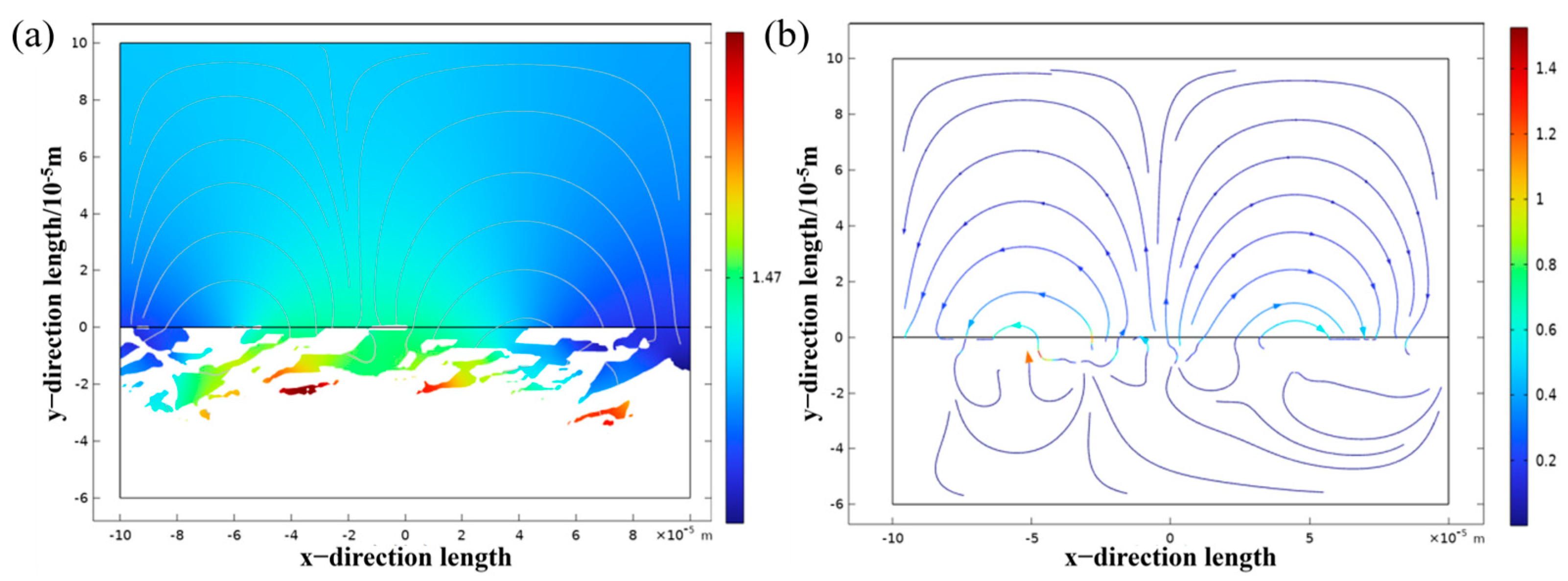

3.3.3. Simulation Analysis of TC4 Titanium Alloy α and β Two-Phase Corrosion

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The hardness of the cladding layer after laser cladding is about 35.17% higher than that of the substrate, and the average hardness inside the cladding layer can reach about 500 HV. The average hardness of the laser power of 1800 W is the highest, indicating that the hardness distribution in the cladding layer is relatively uniform. Conversely, when the laser power is 1000 W, the average hardness is lower, and the internal hardness of the cladding layer fluctuates the most.

- (2)

- When the laser power is 1400 W, the cladding layer has the highest self-corrosion potential (−0.110 V), the lowest corrosion current (0.125 μA·cm−2), the largest polarization resistance (2,056,570 Ω), and the macroscopic performance is the best corrosion resistance. As the laser power increases, the Rct increases first and then decreases. When the laser power increases from 1000 W to 1800 W, the resistance value of Rct gradually increases. When the laser power is 1800 W, the cladding layer has a maximum charge transfer resistance Rct ((5.8864 ± 0.22) × 105), which is much higher than that of the other three groups of experiments.

- (3)

- The results of numerical simulation show that the current density of the β phase is larger than that of the α phase, and the β phase is more susceptible to corrosion. When the α phase and the β phase form a galvanic cell in the electrolyte, the potential of the β phase is lower than that of the α phase, so the electrolyte is always finitely dissolved. Due to the high potential of the α phase, it belongs to the protected party, and no corrosion occurs.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, H.; Zhao, C.; Xie, W.; Wu, D.; Du, B.; Zhang, X.; Wen, M.; Ma, R.; Li, R.; Jiao, J.; et al. Research Progress of Laser Cladding on the Surface of Titanium and Its Alloys. Materials 2023, 16, 3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haochen, L.I.; Lin, F.A.; Haibing, Z.H.; Yingying, W.A.; Junlei, T.A.; Xuehan, B.A.; Mingxian, S.U. Research Progress of Stress Corrosion Cracking of Ti-alloy in Deep Sea Environments. J. Chin. Soc. Corros. Prot. 2022, 42, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, M.; Huang, F.; Wang, Y. Brief Analysis of the application of titanium and titanium alloys in marine equipment. Metal World 2021, 5, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, K.; Radhakrishnan, R.; Wereley, N.M. Advances in gamma titanium aluminides and their manufacturing techniques. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2012, 55, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, F.; Chen, C.; Yu, H. Research status of laser cladding on titanium and its alloys: A review. Mater. Des. 2014, 58, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottam, R.; Brandt, M. Laser cladding of Ti-6Al-4V powder on Ti-6Al-4V substrate: Effect of laser cladding parameters on mi-crostructure. Phys. Procedia 2011, 12, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrasiabi, M.; Keller, D.; Lüthi, C.; Bambach, M.; Wegener, K. Effect of process parameters on melt pool geometry in laser powder bed fusion of metals: A numerical investigation. Procedia CIRP 2022, 113, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinlong, W.; Wenjie, P.; Tianlong, L.; Qingyuan, W.; Zeyu, S.; Gang, Y. Fatigue failure analysis for marine propeller used titanium alloy under salty-water environment with the effect of corrosion durations. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 179, 109805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabhani, M.; Razavi, R.S.; Barekat, M. Corrosion study of laser cladded Ti-6Al-4V alloy in different corrosive environments. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 97, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, P.; Takadoum, J.; Berçot, P. Tribocorrosion of 316L stainless steel and TA6V4 alloy in H2SO4 media. Corros. Sci. 2009, 51, 1308–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, M.; Thanki, A.; Mohanty, S.; Witvrouw, A.; Yang, S.; Thorborg, J.; Tiedje, N.S.; Hattel, J.H. Keyhole-induced porosities in Laser-based Powder Bed Fusion (L-PBF) of Ti6Al4V: High-fidelity modelling and experimental validation. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 30, 100835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paydas, H.; Mertens, A.; Carrus, R.; Lecomte-Beckers, J.; Tchuindjang, J.T. Laser cladding as repair technology for Ti–6Al–4V alloy: Influence of building strategy on microstructure and hardness. Mater. Des. 2015, 85, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.B.; Meng, X.J.; Liu, H.Q.; Shi, G.L.; Wu, S.H.; Sun, C.F.; Wang, M.D.; Qi, L.H. Development and characterization of laser clad high temperature self-lubricating wear resistant composite coatings on Ti–6Al–4V alloy. Mater. Des. 2014, 55, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohidul Alam, M.; Haseeb, A. Response of Ti-6Al-4V and Ti-24Al-11Nb alloys to dry sliding wear against hardened steel. Tri-Bol. Int. 2002, 35, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, A.; Straffelini, G.; Tesi, B.; Bacci, T. Dry sliding wear mechanisms of the Ti6Al4V alloy. Wear 1997, 208, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.X.; Li, Y.; Wang, S. Study on the wear behavior and wear mechanism of TC4 alloy in different environmental media. Rare Met. 2015, 39, 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.Y.; Hu, Y.L.; Tong, Y.; Cai, Z.H.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.D.; Liao, J.Z.; Xu, S.; Li, L.K. Wear-resistant NbMoTaWTi high entropy alloy coating prepared by laser cladding on TC4 titanium alloy. Tribol. Int. 2023, 182, 108366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, M.; Geary, A.L. Electrochemical polarization: I. A theoretical analysis of the shape of polarization curves. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1957, 104, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, Q. Effect of electrochemical state on corrosion–wear behaviors of TC4 alloy in artificial seawater. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2016, 26, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, D.T.; Day, R.J. Kinetics for oxygen reduction at platinum, palladium and silver electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 1963, 8, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, N. Green Corrosion Chemistry and Engineering; Sharma, S.K., Ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2011; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, P.; Song, R.; Li, X.J.; Deng, J.; Chen, Z.Y.; Li, Q.W.; Wang, K.S.; Cao, W.C.; Liu, D.X.; Yu, H.L. Influence of concentrations of chloride ions on electrochemical corrosion behavior of titanium-zirconium-molybdenum alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 708, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linqing, W.; Yongtao, Z.; Junjun, W.; Zhongwei, W.A.; Weijiu, H.U. Corrosion-wear interaction behavior of TC4 titanium alloy in simulated seawater. Tribology 2019, 39, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Song, Y.; Dong, K.; Han, E.H. Research progress on the corrosion behavior of titanium alloys. Corros. Rev. 2023, 41, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.F.; Hu, J.N.; Shi, J.J.; Gao, X.W.; Li, J.Z. Effect of heat treatment on microstructure and corrosion resistance of TC4 titanium alloy manufactured by additive. Trans. Mater. Heat Treat. 2023, 44, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.Q.; Li, L.; Wang, Q.; Xin, C.; Gao, Q.; Li, J.C.; Xue, H.T.; Lu, X.F.; Tang, F.L. Effect of environmental media on the growth rate of fatigue crack in TC4 titanium alloy: Seawater and air. Corros. Sci. 2024, 230, 111941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Song, Y.; Dong, K.; Shan, D.; Han, E.H. Corrosion behavior of dual-phase Ti–6Al–4V alloys: A discussion on the impact of Fe content. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 858, 157708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Huang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Alexandrov, I.V.; Chang, H.; Dan, Z.; Ma, L.; Zhou, L. Stress corrosion cracking of TC4 ELI alloy with different microstructure in 3.5% NaCl solution. Mater. Charact. 2022, 194, 112357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Density | Melting Point | Tensile Strength | Yield Strength | Coefficient of Linear Expansion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.5 g/cm3 | 1660 °C | 950 MPa | 880 MPa | 8.8 × 10−6/K |

| Element | Al | V | Fe | O | Ti |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wt. % | 5.5–6.76 | 3.5–4.5 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.2 | Bal. |

| Element | Ti | Al | V | Fe | C | N | H | O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wt. % | Bal. | 5.5–6.8 | 3.5–4.5 | ≤0.3 | ≤0.1 | ≤0.05 | ≤0.015 | ≤0.20 |

| P/W | Ecorr/V | icorr/μA·cm−2 | βa | βc | Rp/Ω·cm2 | vcorr/mm·a−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub | −0.469 | 0.247 | 5.887 | 4.101 | 237,669 | 3.019 × 10−3 |

| 1000 | −0.221 | 0.664 | 8.879 | 5.665 | 2.165 × 106 | 6.691 × 10−4 |

| 1400 | −0.110 | 0.125 | 8.125 | 7.368 | 2.057 × 106 | 9.299 × 10−4 |

| 1800 | −0.118 | 2.970 | 5.893 | 6.564 | 1.784 × 106 | 2.823 × 10−4 |

| 2200 | −0.156 | 2.605 | 6.786 | 7.457 | 2.563 × 106 | 2.356 × 10−4 |

| P/W | Rs/ Ω·cm−2 | (Q1 − Y)/ 10−5·Ω−1·s−n·cm−2 | n1 | Rd/ 105 Ω·cm−2 | (Q2 − Y)/ 10−5·Ω−1·s−n·cm−2 | n2 | Rct/ 105·Ω·cm−2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 | 66.16 ± 2.5 | 1.06 ± 0.08 | 0.86 ± 0.02 | 0.936 ± 0.05 | (5.71 ± 0.12) | 0.87 ± 0.01 | 4.5854 ± 0.15 |

| 1400 | 63.33 ± 2.1 | 3.75 ± 0.15 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 1.323 ± 0.07 | (5.65 ± 0.10) | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 5.5496 ± 0.18 |

| 1800 | 64.98 ± 2.3 | 6.39 ± 0.20 | 0.89 ± 0.01 | 4.117 ± 0.12 | (3.45 ± 0.08) | 0.89 ± 0.01 | 5.8864 ± 0.22 |

| 2200 | 62.35 ± 2.0 | 1.00 ± 0.05 | 0.79 ± 0.02 | 3.797 ± 0.10 | (4.48 ± 0.11) | 0.77 ± 0.02 | 3.8318 ± 0.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, K.; Cui, L.; Guo, S.; Zheng, B.; Cui, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, C. Effect of Laser Power on the Corrosion and Wear Resistance of Laser Cladding TC4 Alloy. Materials 2025, 18, 5609. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245609

Li X, Zhao S, Zhang K, Cui L, Guo S, Zheng B, Cui Y, Chen Y, Zhao Y, Xu C. Effect of Laser Power on the Corrosion and Wear Resistance of Laser Cladding TC4 Alloy. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5609. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245609

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiaolei, Sen Zhao, Kelun Zhang, Lujun Cui, Shirui Guo, Bo Zheng, Yinghao Cui, Yongqian Chen, Yue Zhao, and Chunjie Xu. 2025. "Effect of Laser Power on the Corrosion and Wear Resistance of Laser Cladding TC4 Alloy" Materials 18, no. 24: 5609. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245609

APA StyleLi, X., Zhao, S., Zhang, K., Cui, L., Guo, S., Zheng, B., Cui, Y., Chen, Y., Zhao, Y., & Xu, C. (2025). Effect of Laser Power on the Corrosion and Wear Resistance of Laser Cladding TC4 Alloy. Materials, 18(24), 5609. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245609