Numerical Investigation on Tensile and Compressive Properties of 3D Four-Directional Braided Composites

Abstract

1. Introduction

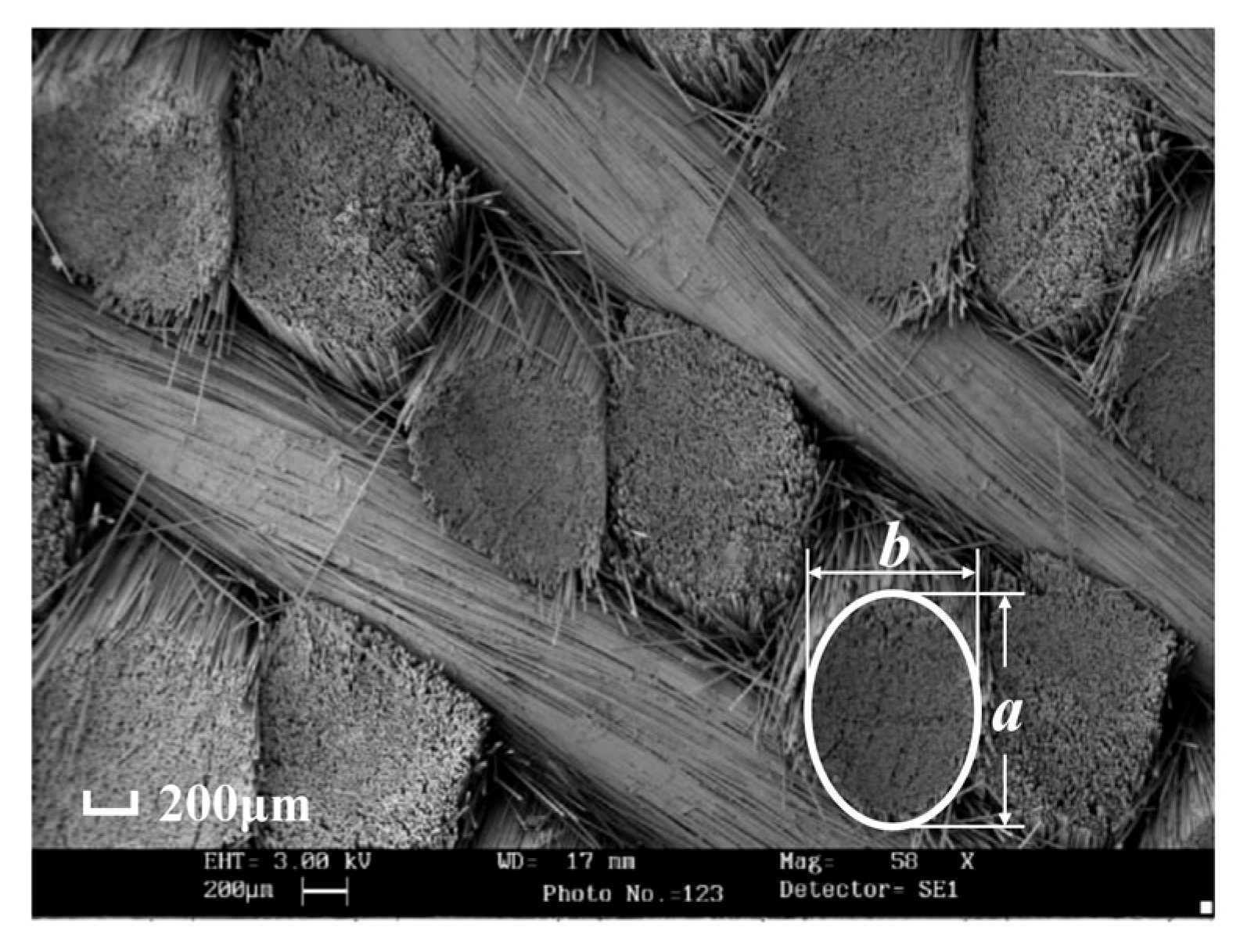

2. Materials and Tests

3. Methods

3.1. Material Properties

3.2. Progressive Damage Model

3.3. Damage Evolution Model

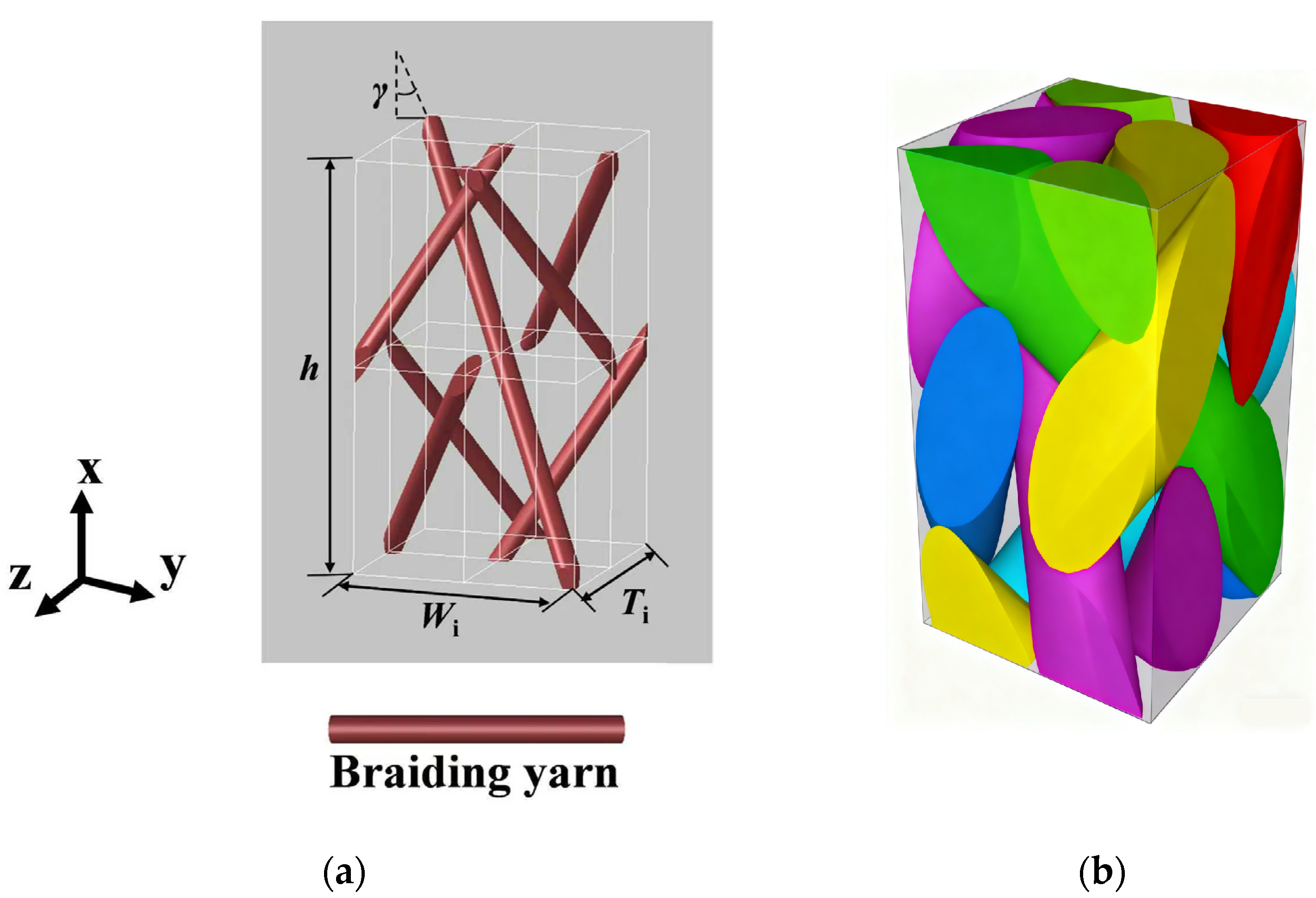

4. Mesoscopic FE Model

4.1. Geometric Structure of Unit-Cell

4.2. Boundary Conditions

4.3. Mesh Discretization

5. Results

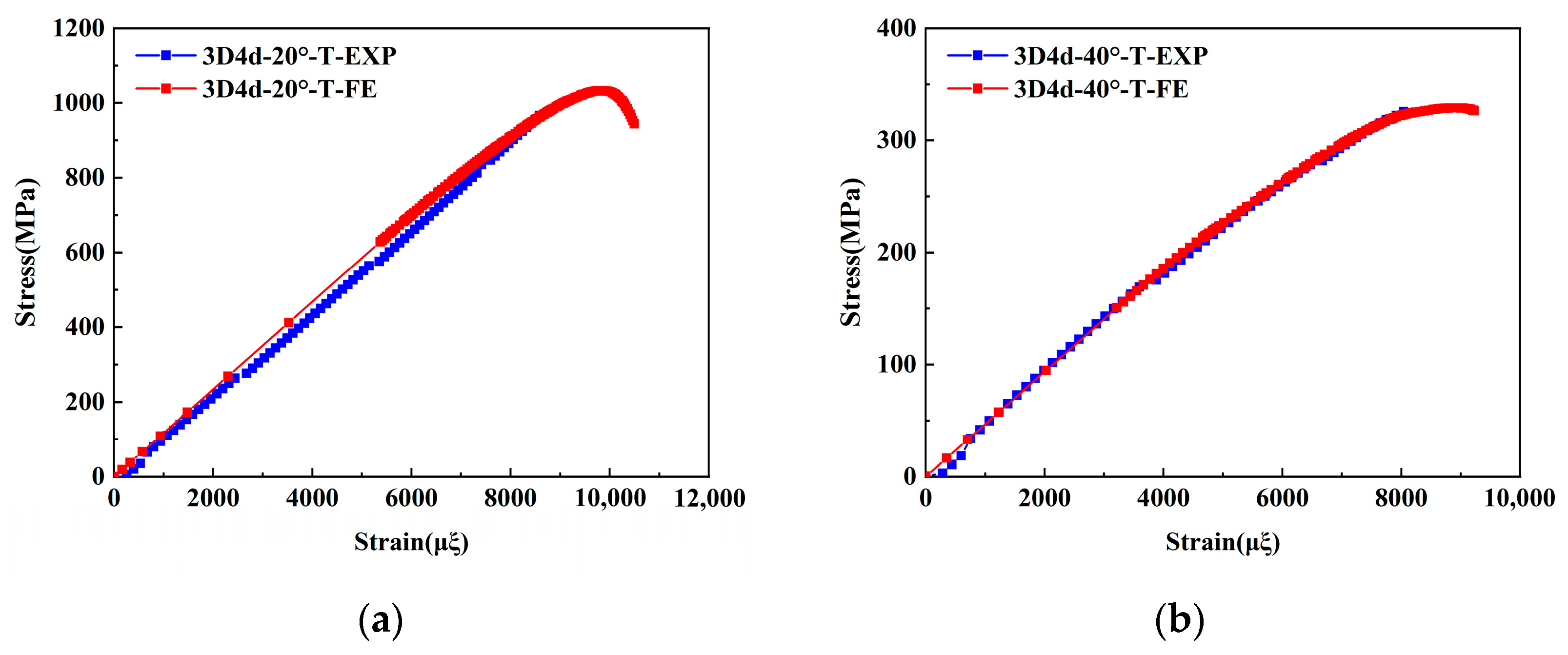

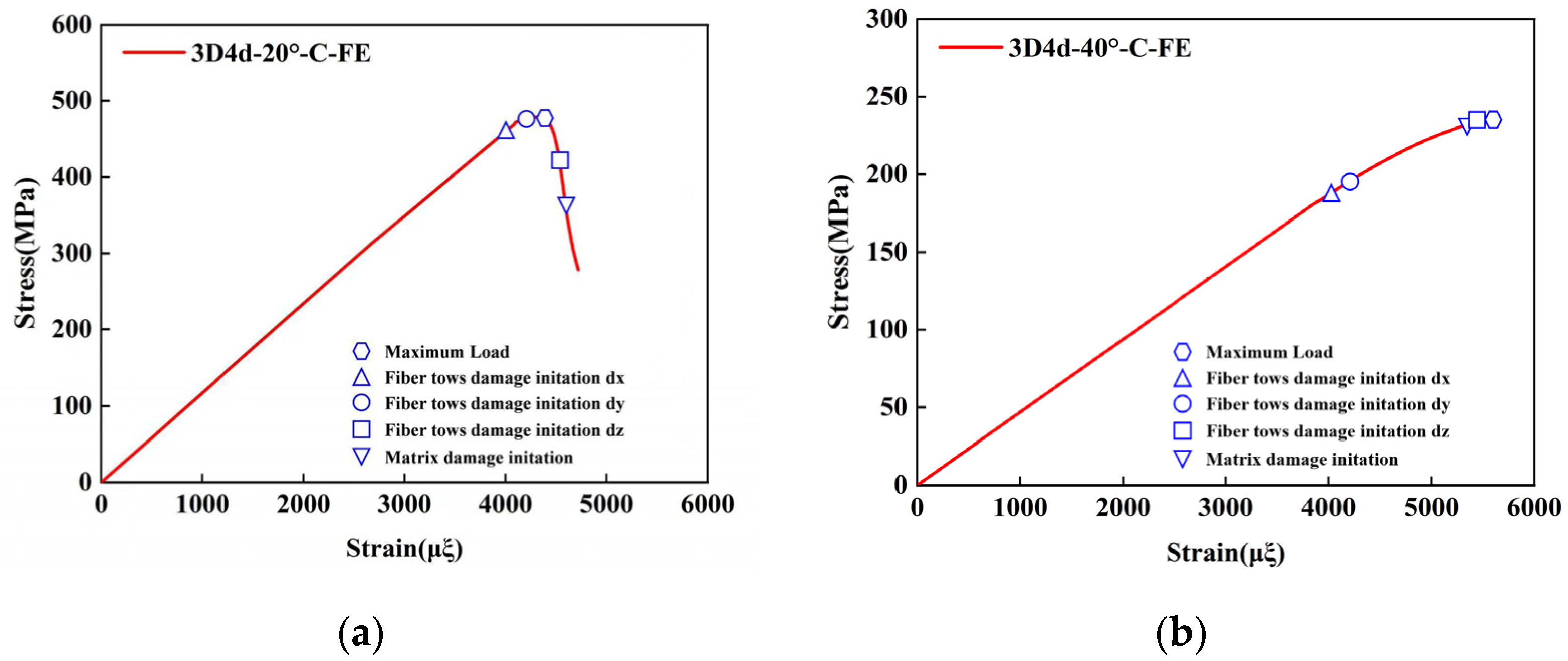

5.1. Mechanical Behavior

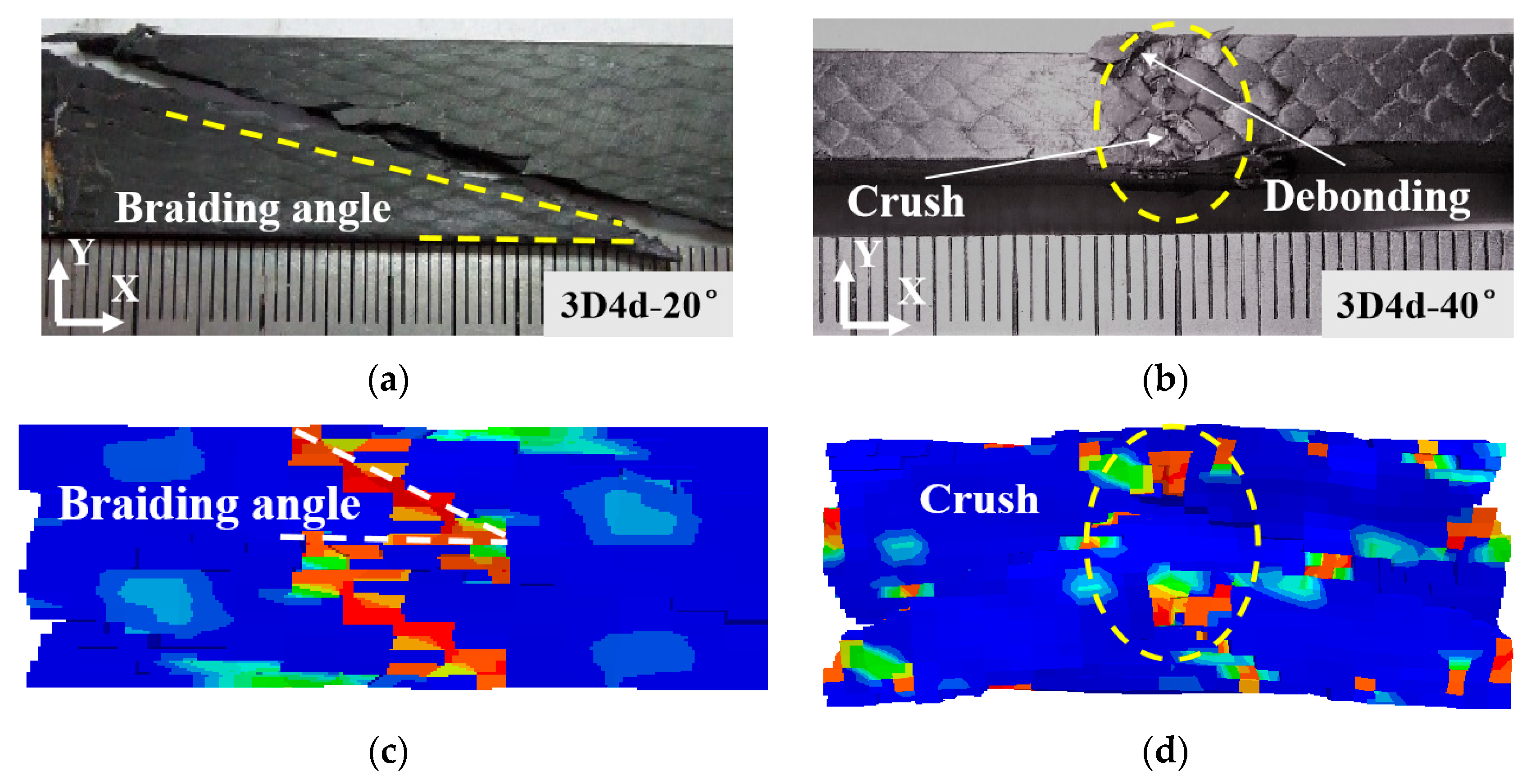

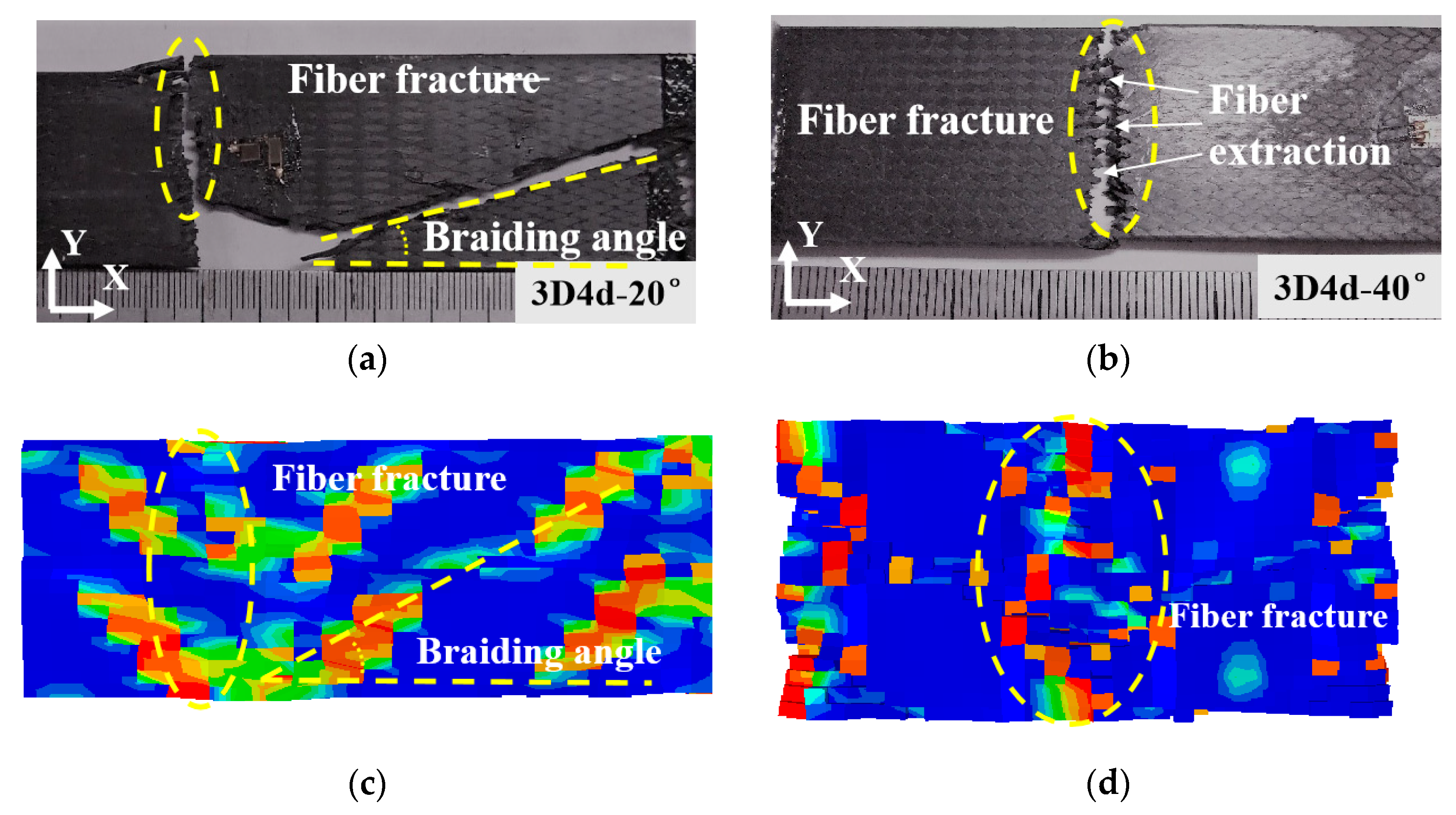

5.2. Failure Modes

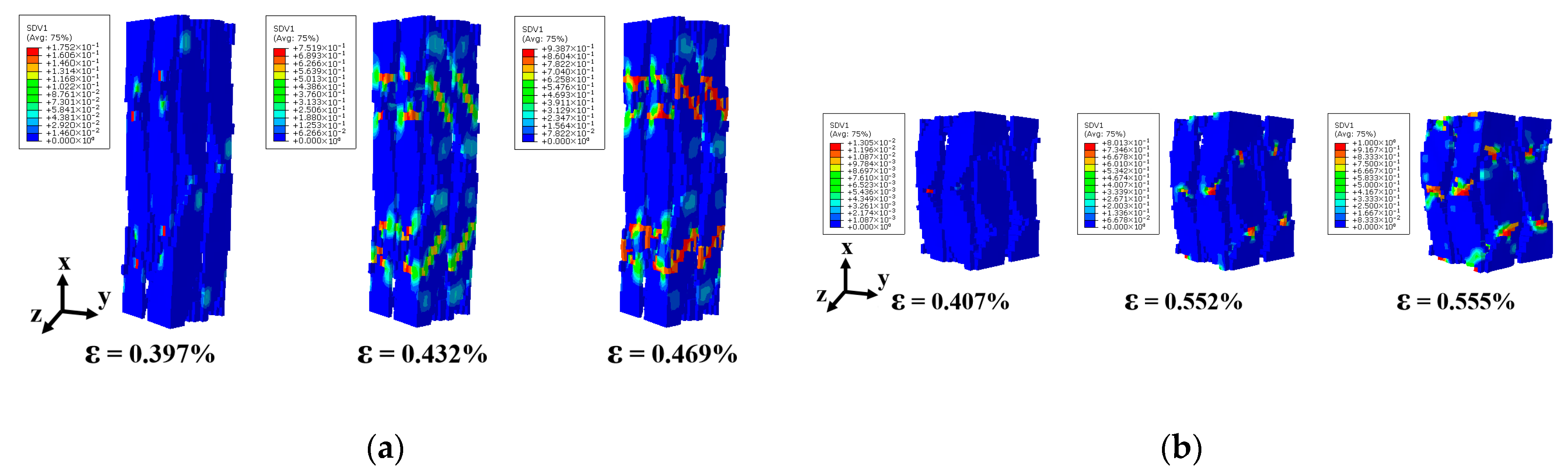

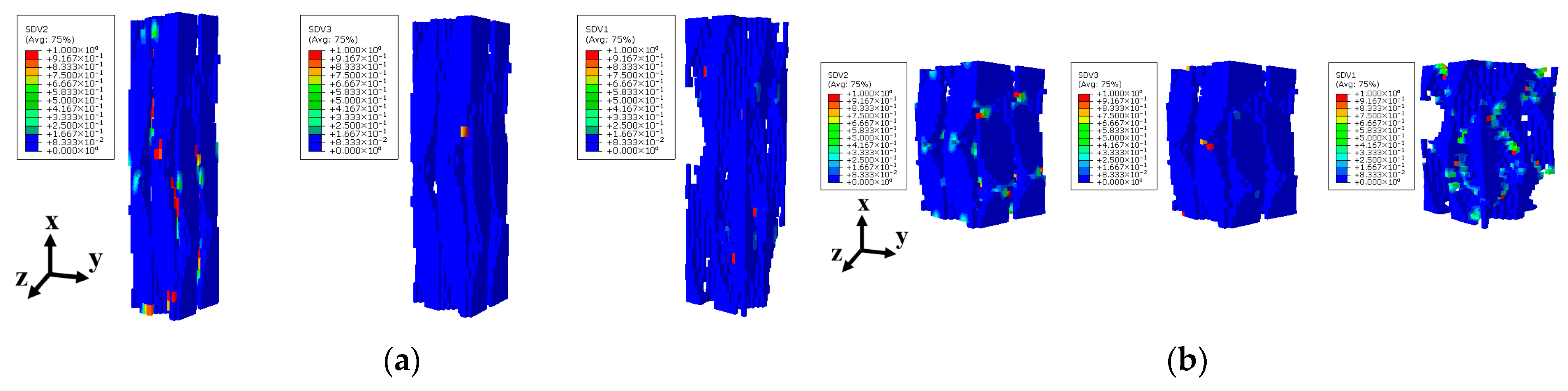

5.3. Prediction of Damage Mechanism

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The proposed micro-scale FE model accurately predicts the longitudinal compressive and tensile responses of 3D4d braided composites, with a maximum deviation of less than 8% from experimental data. This validates the model’s ability to capture the anisotropic mechanical behavior and brittle fracture characteristics of the composites under various loading conditions, providing a reliable computational tool for optimizing design parameters and reducing experimental costs.

- (2)

- The compressive modulus and strength of 3D4d braided composites decrease with increasing internal braiding angle, while the compressive failure strain increases. This is attributed to the irregular spatial arrangement of fibers at larger braiding angles, which reduces the effective stiffness but enhances the strain capacity. Conversely, under tensile loading, the tensile modulus and strength decrease with increasing braiding angle, attributed to reduced fiber alignment along the loading axis. Smaller braiding angles enhance fiber continuity and increase the tensile failure strain, while larger angles promote matrix cracking and interfacial debonding. These findings highlight the trade-off between stiffness and ductility governed by braiding geometry, offering valuable guidance for optimizing material performance in engineering applications.

- (3)

- The tensile-to-compressive strength ratio of 3D four-directional braided composites exhibits a significant decrease with increasing braiding angle. This reduction stems from a fundamental transition in failure mechanisms: at low braiding angles, failure is dominated by fiber fracture in tension and fiber micro-buckling in compression, representing distinct mechanisms. In contrast, at high braiding angles, both tensile and compressive failures become governed by matrix shear and interfacial debonding, resulting in convergent failure modes.

- (4)

- Distinct damage mechanisms are observed in composites with different braiding angles: 3D4d-20° composites exhibit fiber bundle axial fracture and matrix cracking under compression, whereas 3D4d-40° composites show matrix-dominated damage and central crushing. Under tensile loading, 3D4d-20° composites experience fiber pull-out and shear failure, whereas 3D4d-40° composites exhibit perpendicular fiber fracture. These differences underscore the critical role of braiding angle in governing damage propagation paths and failure mechanisms, which is essential for predicting service-life performance and enhancing structural reliability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jin, F.; Zhao, Z.H.; Liu, L.L.; Zhu, X.Y.; Chen, W.; Luo, G. Multi-scale prediction method for ice impact resistance of 3D braided composites based on surface-inner cell model. Compos. Struct. 2025, 363, 119142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.N.; Quan, Z.Z.; Ren, W.; Qin, X.H.; Yu, J.Y. Multifunctional 3D carbon fiber/epoxy braided composites with excellent compression performance and electromagnetic interference shielding. Mater. Lett. 2024, 372, 137036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.H.; Liu, L.L.; Xu, K.L.; Luo, G.; Zhao, Z.H. Ice-ball impact analysis method and verification of three-dimensional braided composites based on surface unit-cell and interior unit-cell modeling. J. Aeronaut. Mater. 2023, 43, 106–114. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, M.Y.; Zhang, D.T.; Qian, K. Quantitative characterization of low-velocity impact damage in three dimensional five-directional braided composites. Acta Mater. Compos. Sin. 2023, 40, 5411–5422. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, Y.J.; Kim, J.-H.; Lee, D.H.; Chon, J.S.; Lee, S.J.; Kwon, D.-J. Comprehensive analysis of the effect of braiding angle on the wettability and mechanical properties of 3D braided carbon fiber fabric-reinforced composites. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Bai, L.T.; Yang, X.H.; Xue, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, S.H.; Chen, X.F.; Guan, Z.W.; et al. Multi-scale characterisation and damage analysis of 3D braided composites under off-axis tensile loading. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2025, 261, 111017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wen, D.Y.; Shen, Q.L.; Liang, J.H.; Chen, Y.; Fang, Z.; Zhang, M.Y.; Cheng, S.Q.; Gao, Y.X.; Gao, X.Z. A novel modeling method to study compressive behaviors of 3D braided composites considering effects of fiber breakage and waviness defects. Compos. Struct. 2024, 340, 118206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.X.; Chen, L.; Du, Q. Technical difficulties and thoughts of Ma8 scramjet engine. J. Rocket Propuls. 2025, 51, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Xiong, J.-J. Nonlinear thermo-mechanical coupling behaviours and damage mechanisms of 3D braided composites subjected to longitudinal and transverse tensile at room and elevated temperatures. Forces Mech. 2025, 21, 100336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, K.; Xu, X.W.; Bui, T.Q.; Sun, T.; Zhang, C. Mechanical properties and macro–meso coupled damage behavior of three-dimensional four-directional braided composites under bending loading. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2023, 31, 3829–3843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.X.; Hu, Q. Experimental investigation into the compressive mechanical properties of three dimensional braided composites. Acta Mater. Compos. Sin. 2003, 20, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, S.; Sun, Y.G.; Wu, L.Z.; Du, S.Y. Compressive experimental investigation of 3D 4-directional braided composites board on mesoscopic failure mechanism. Acta Mater. Compos. Sin. 2007, 24, 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.S.; Liu, Z.X.; Lu, Z.X.; Feng, Z.H. Compressive properties and failure mechanism of three dimensional and five directional carbon fiber/phenolic braided composites. Acta Mater. Compos. Sin. 2008, 25, 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Wu, L.Z.; Yang, Y.H.; Zhou, Z.G. Experimental investigation on tensile mechanical properties of 3D six-directional braided composite. J. Astronaut. 2012, 33, 669–674. [Google Scholar]

- Boris, D.; Xavier, L.; Damien, S. The tensile behaviour of biaxial and triaxial braided fabrics. J. Ind. Text. 2018, 47, 2184–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zheng, X.T.; Zhou, J.; Song, X.Y.; Jia, P.; Liu, H.B.; Liu, X.H. Effect of braiding architectures on the mechanical and failure behavior of 3D braided composites:Experimental investigation. Polymers 2022, 14, 1916. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, J.R.; He, C.; Liang, J.; Chen, Y.F. A coupled elastic-plastic damage model for the mechanical behavior of three-dimensional (3D) braided composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2018, 157, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.; Wang, B.; Liang, J. A coupled FE-FFT multiscale method for progressive damage analysis of 3D braided composite beam under bending load. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2019, 181, 107691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.Z.; Fan, J. Progressive damage simulation of 3D four-directional braided composites based on surface-interior unit-cells models. Acta Mater. Compos. Sin. 2021, 38, 545–556. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.Y.; Chen, L. A review of multi-scale numerical modeling of three-dimensional woven fabric. Compos. Struct. 2021, 263, 113685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereke, T.; Cherif, C. A review of numerical models for 3d woven composite reinforcements. Compos. Struct. 2019, 209, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.J.; Kong, X.X.; Zhai, J.J.; Zhang, N.X.; Guo, Z.T.; Yan, S.; Guo, H.Y. Advances in diversified structural design, modeling and modification of 3D braided composites. Thin-Walled Struct. 2025, 218 Pt B, 114071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.Y.; Zhou, J.; Yeoh, K.M.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, S.H.; Raju, K.; Chen, X.F.; Guan, Z.W.; Cantwell, W.J.; Tan, V.B.C. Multiscale modelling of residual thermal stresses and off-axis bending in 3D braided composites. Compos. Part B 2025, 308, 112972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.Y.; Li, C.G.; Chi, X.F.; Sun, Y.Z. Influence of process configuration and mandrel geometry variations on the mechanical behavior of 3D braided composites subjected to quasi-static loads. Compos. Part B 2025, 306, 112794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Gu, B.H.; Sun, B.Z. Dielectric breakdown behaviors and high-voltage damages of 3D braided carbon fiber/epoxy resin composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2025, 272, 111388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.; Hahn, H. Designing with 4-step braided fabric composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1996, 56, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D3039; Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Polymer Matrix Composite Materials. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

- ASTM D6641; Standard Test Method for Compressive Properties of Polymer Matrix Composite Materials Using a Combined Loading Compression (CLC) Test Fixture. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- Huang, Z.M. A bridging model prediction of the ultimate strength of composite laminates subjected to biaxial loads. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2004, 64, 395–448, Erratum in Compos. Sci. Technol. 2004, 64, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamis, C.C. Mechanics of composite materials: Past, present, and future. J. Compos. Technol. Res. 1989, 11, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, R.M. 2013 timoshenko medal award paper—Completion and closure on failure criteria for unidirectional fiber composite materials. J. Appl. Mech. 2014, 81, 011011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddour, A.S.; Hinton, M.J. Maturity of 3d failure criteria for fibre-reinforced composites: Comparison between theories and experiments: Part B of WWFE-II. J. Compos. Mater. 2013, 47, 925–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddour, A.S.; Hinton, M.J.; Smith, P.A.; Li, S. A comparison between the predictive capability of matrix cracking, damage and failure criteria for fibre reinforced composite laminates: Part a of the third world-wide failure exercise. J. Compos. Mater. 2013, 47, 2749–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashin, Z. Failure criteria for unidirectional fiber composites. J. Appl. Mech. 1980, 47, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.P.; Petrinic, N.; Ruiz, C.; Achard, F. Prediction of impact damage in composite plates. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2000, 60, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, R.M. A comprehensive theory of yielding and failure for isotropic materials. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 2007, 129, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.H.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, D.; Song, X.Y.; Yang, X.H.; Bai, L.T.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.F.; Guan, Z.W.; Cantwell, W.J. Effect of braiding architecture on the tensile properties and damage mechanisms of 3D braided composites. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, 678–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Liu, Z.L.; Xia, B.; Duan, S.H.; Nie, X.H.; Zhuang, Z. Development of a new constitutive model considering the shearing effect for aniso-tropic progressive damage in fiber-reinforced composites. Compos. Part B 2015, 75, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, S. Mechanical modeling of material damage. J. Appl. Mech. 1988, 55, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, J.; Chen, X.F.; Zhang, S.H.; Bai, L.T.; Yang, X.H.; Du, F.P.; Guan, Z.W.; Zheng, X.T.; et al. Hierarchical multi-scale analysis of the effect of varying fiber bundle geometric properties on the mechanical properties of 3D braided composites. Compos. Struct. 2023, 322, 117375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.L. Three-cell model and 5D braided structural composite. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1996, 56, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.G.; Wongsto, A. Unit cells for micromechanical analyses of particle-reinforced composites. Mech. Mater. 2004, 36, 543–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.G. Boundary conditions for unit cells from periodic microstructures and their implications. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2008, 68, 1962–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Du, X.B.; Li, D.S.; Jiang, L. Investigation of parameterized braiding parameters and loading directions on compressive behavior and failure mechanism of 3D four-directional braided composites. Compos. Struct. 2022, 287, 115357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.D.; Liang, J.; Han, J.C. Experimental and Numerical Study of Mechanical Properties of Three Dimensional Four Directional Braided Composites. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Composites Materials, ICCM 2011, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 21–26 August 2011; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282676143 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Xu, K.; Xu, X.W. Nonlinear numerical analysis of progressive damage of 3d braided composites. Chin. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2007, 39, 398–407. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.G.; Zou, S.M.; Zhou, W.X.; Huang, Y.; Shao, L.W.; Yuan, J.; Gou, X.N.; Jin, W.; Wang, Z.B.; Chen, X.; et al. Clinically applicable histopathological diagnosis system for gastric cancer detection using deep learning. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, H.; Wu, J.; Dahal, S.; Joo, T.; Garg, N. Automated estimation of cementitious sorptivity via computer vision. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| T700 | |

|---|---|

| /GPa | 230 |

| /GPa | 18.2 |

| 0.27 | |

| 0.30 | |

| /GPa | 36.6 |

| /GPa | 7.0 |

| /GPa | 4.9 |

| /GPa | 1.4 |

| GXt (N/mm) | GXc (N/mm) | GYt (N/mm) | GYc (N/mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12.78 | 6.26 | 0.13 | 1.15 |

| Gmt (N/mm) | Gmc (N/mm) |

|---|---|

| 1.0 | 1.0 |

| TDE86 | |

|---|---|

| /GPa | 3.45 |

| 0.35 | |

| /GPa | 0.08 |

| /GPa | 0.180 |

| /GPa | 0.2 |

| Modulus (GPa) | Strength (MPa) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | FE | EXP | Relative Error | FE | EXP | Relative Error |

| 3D4d-20°-C | 114.8 | 108.7 | 5.6% | 478.4 | 453.9 | 5.4% |

| 3D4d-40°-C | 46.9 | 43.6 | 7.6% | 236 | 226.6 | 4.1% |

| 3D4d-20°-T | 117.2 | 110.7 | 6.0% | 1032.5 | 966.3 | 6.4% |

| 3D4d-40°-T | 49.5 | 46.8 | 5.4% | 326.2 | 325.5 | 0.3% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, L.; Dou, F.; Wang, J.; Li, G.; Li, B.; Zhou, J.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, D. Numerical Investigation on Tensile and Compressive Properties of 3D Four-Directional Braided Composites. Materials 2025, 18, 5592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245592

Chen L, Dou F, Wang J, Li G, Li B, Zhou J, Xue Y, Zhang S, Zhang D. Numerical Investigation on Tensile and Compressive Properties of 3D Four-Directional Braided Composites. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245592

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Longcan, Feilong Dou, Jun Wang, Guangxi Li, Binchao Li, Jin Zhou, Yong Xue, Shenghao Zhang, and Di Zhang. 2025. "Numerical Investigation on Tensile and Compressive Properties of 3D Four-Directional Braided Composites" Materials 18, no. 24: 5592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245592

APA StyleChen, L., Dou, F., Wang, J., Li, G., Li, B., Zhou, J., Xue, Y., Zhang, S., & Zhang, D. (2025). Numerical Investigation on Tensile and Compressive Properties of 3D Four-Directional Braided Composites. Materials, 18(24), 5592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245592