Transformation of Waste Glasses in Hydroxide Solution

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials

3. Experimental and Methods of Characterization

4. Results and Discussion

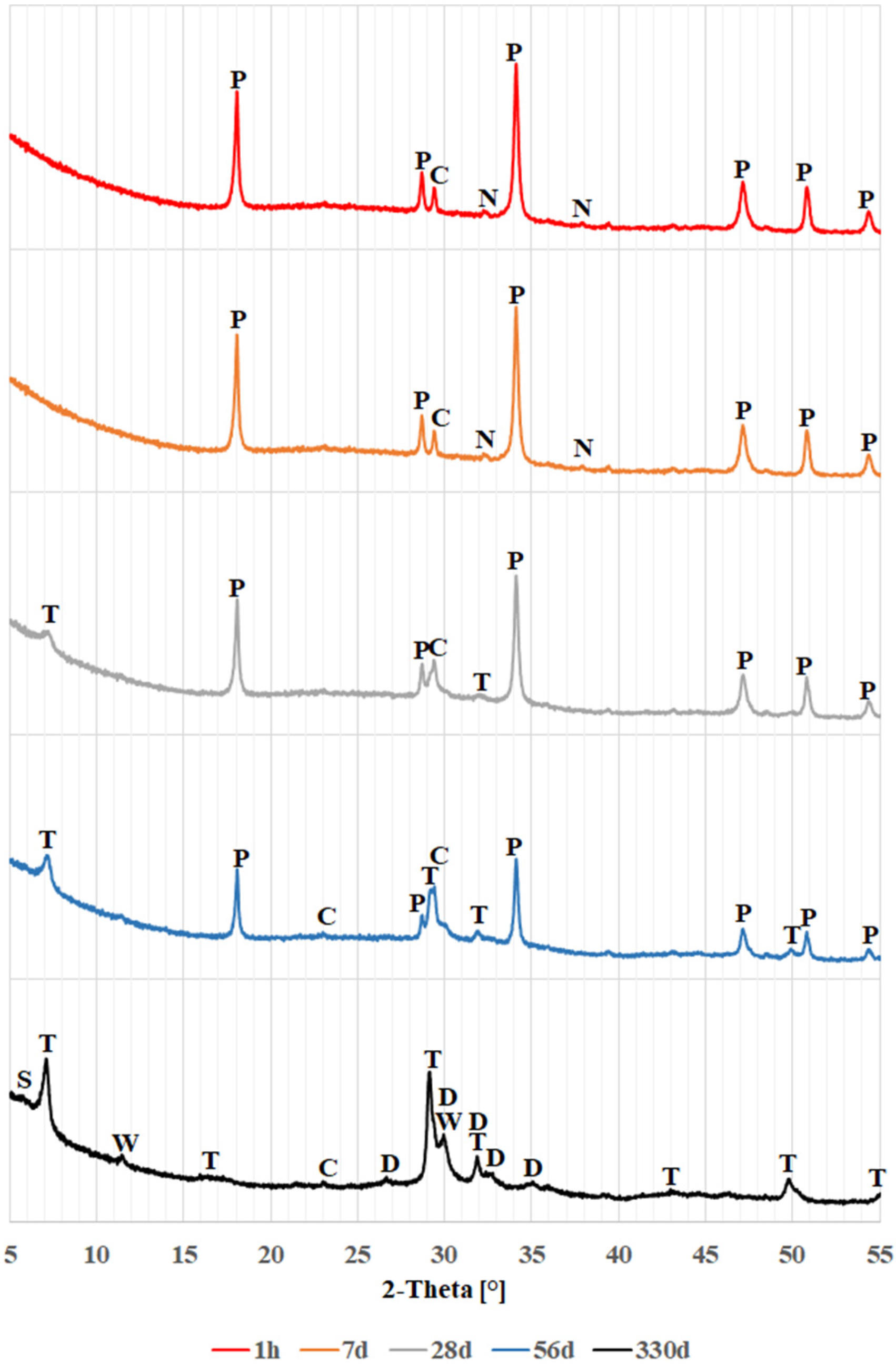

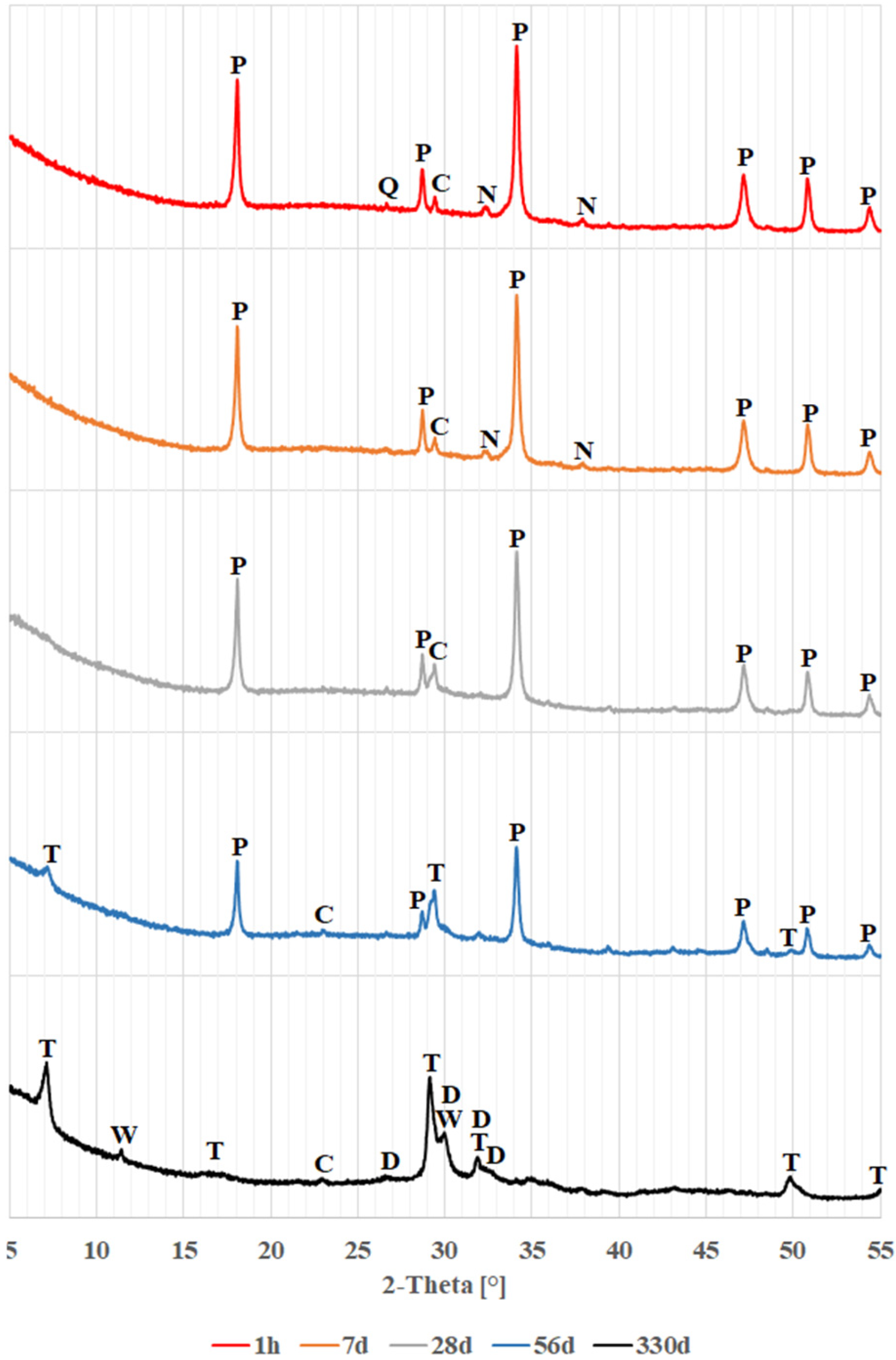

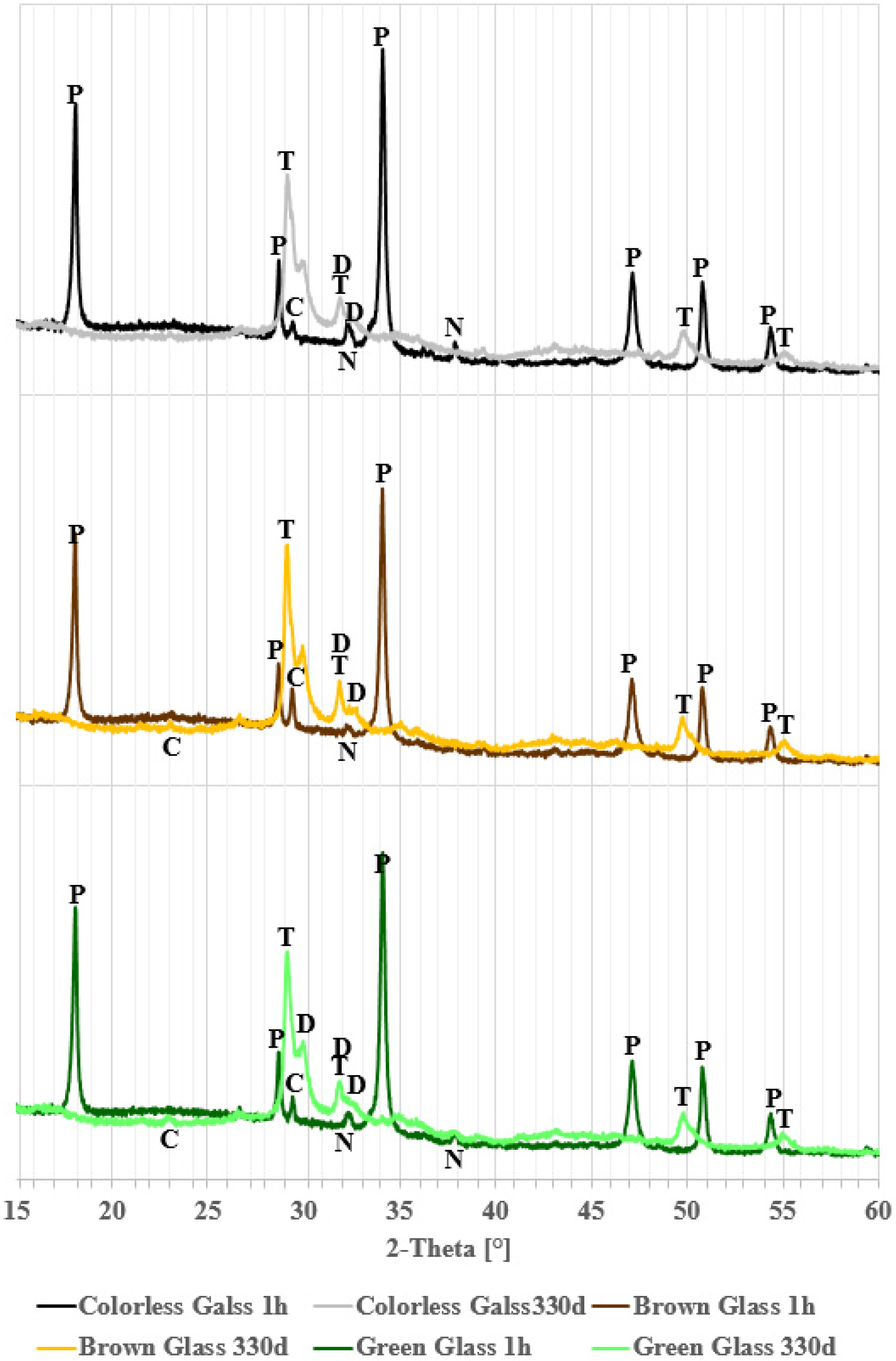

4.1. Phase Analysis (XRD)

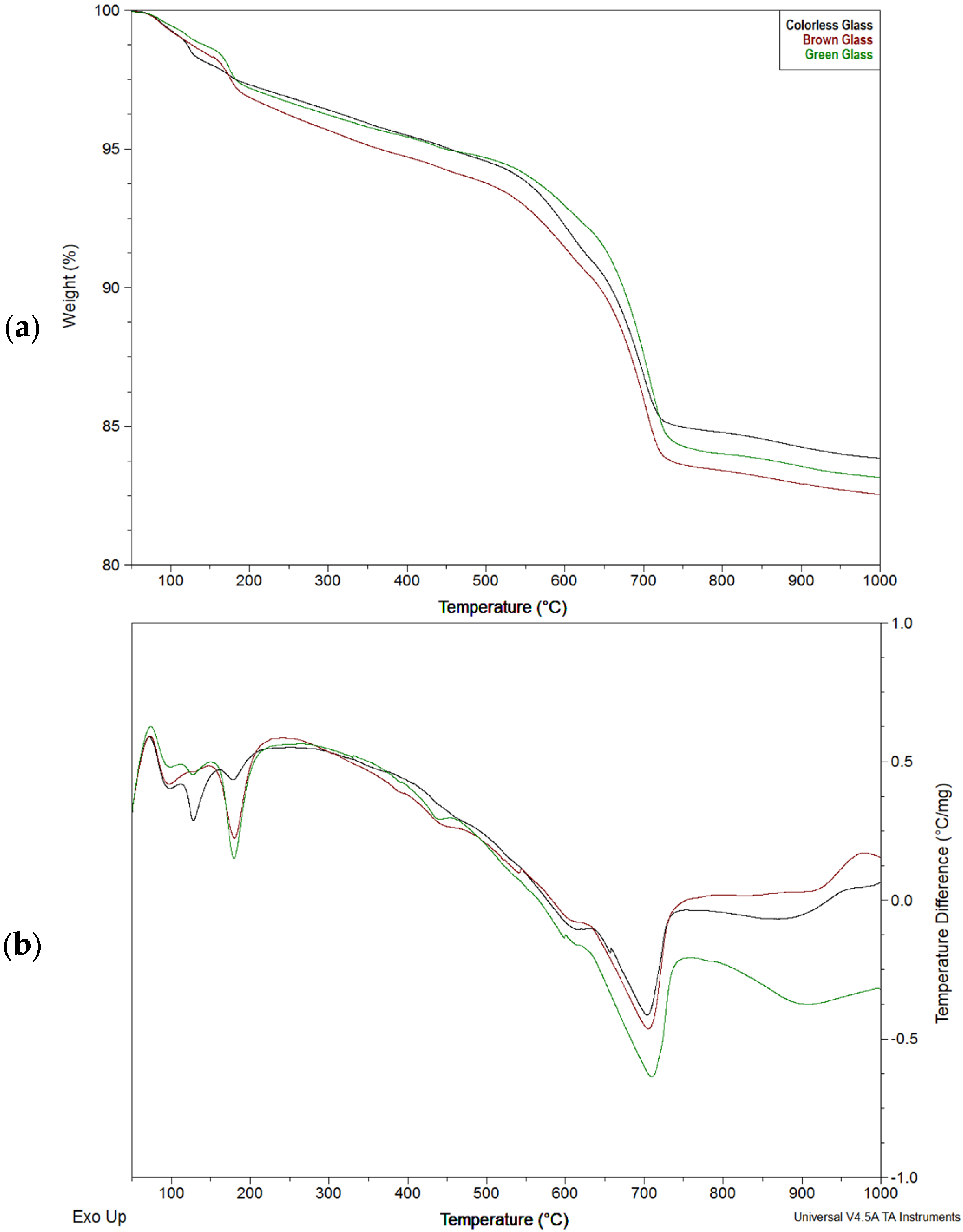

4.2. Phase Analysis (DTA–TG)

4.3. Microstructure Analysis (SEM-EDS)

5. Conclusions

- -

- Regardless of the color of the soda-lime glass, a pozzolanic reaction occurs when the glass powders come into contact with the calcium and sodium hydroxide solution, resulting in the formation of hydrated calcium silicates.

- -

- The pozzolanic reaction of glass powders first produces hydrated calcium silicates structurally similar to tobermorite, later transforming into dellaite. It remains unclear whether dellaite-like structures result from the transformation of tobermorite-like products or form directly from the glass powder. Simultaneously, the background related to amorphous glass decreases, while that associated with amorphous calcium silicates increases.

- -

- Higher levels of magnesium and iron oxides may lead to the formation of other products, such as saponite.

- -

- Green glass, rich in chromium, reacts more slowly than clear or brown glass but forms a denser microstructure.

- -

- For practical or performance evaluations, it could be beneficial to separate green glass from mixed cullet, due to its different characteristics.

- -

- After 330 days, the complete pozzolanic reaction is confirmed by the total consumption of calcium hydroxide, as shown by XRD and SEM analyses.

- -

- Additional detailed thermal studies are recommended to identify which decomposition phases produce maximum thermal effects at 125, 180, and 440 °C.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Handke, M. Crystallochemistry of Silicates; AGH: Krakow, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ziemba, B. Technologia Szkła; Arkady: Warsaw, Poland, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, A. Chemistry of Glasses; Chapman and Hall: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdowski, W. Cement and Concrete Chemistry; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Holleman, A.F.; Wyberg, E. Lehrbuch der Anorganishen Chemia; Walter Gruyter Verlag: Berlin, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Broekmans, M.A.T.M. Structural properties of quartz and their potential role for ASR. Mater. Charact. 2004, 53, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sordoń-Kulibaba, B. Zagospodarowanie odpadów szkła i opakowań szklanych. Recykling 2008, 3, 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kuśnierz, A. Glass recycling. Pr. Inst. Ceram. Mater. Bud. 2010, 3, 22–33. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-de-Oliveira, L.; Castro-Gomes, J.P.; Santos, P.M.S. The potential pozzolanic activity of glass and red-clay ceramic waste as cement mortars components. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 31, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.L.; Soares, S.M.; Freitas, T.O.G.; Oliveira Júnoir, A.; Ferraira, E.B.; Silva Ferreira, F.G. Evaluation of the Pozzolanic Activity of Glass Powder in Three Maximum Grain Sizes. Mater. Res. 2021, 24, e20200496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbu, O.; Ioani, A.M.; Abdullah, M.M.A.B.; Meiţă, V.; Szilagyi, H.; Sandu, A.V. The pozzoolanic activity level of powder waste glass in comparisons with other powders. Key Eng. Mater. 2015, 660, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idir, R.; Cyr, M.; Tagnit-Hamou, A. Pozzolanic properties of fine and coarse color-mixed glass cullet. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2011, 33, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khmiri, A.; Samet, B.; Chaabuoni, M. Assessement of the waste glass powder pozzolanic activity by different methods. IJRRAS Int. J. Res. Rev. Appl. Sci. 2012, 10, 322–328. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, C.M.; Scarponi, N.B.; Villagrán, Y.A.; Manzanal, D.G.; Piqué, T.M. Pozzolanic activity quantification of hollow glass microspheres. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 118, 103981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Tang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Yu, Z.; Cheng, Q.; Wang, Y. Amulti-objective optimisation approach for activity excitation of waste glass mortar. JMR&T J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 17, 2280–2304. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G.; Ling, T.-C.; Wong, Y.-L.; Poon, C.-S. Effect of crushed glass cullet sizes, casting methods and pozzolanic materials on ASR of concrete block. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 2611–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yannick, T.L.; Arnold, L.L.; Japhet, T.D.; Leroy, M.N.L.; Bruno, T.B.; Ismaïla, N. Properties of eco-friendly cement mortar designed with grounded lead glass used as supplementary cementitious material. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-EN 206+A2:2021-08; Beton-Wymagania, Właściwości Użytkowe, Produkcja i Zgodność. Polish Committee for Standarization: Warsaw, Poland, 2021.

- Tkaczewska, E.; Sitarz, M. The effect of glass structure on the pozzolanic activity of siliceous fly ashes. Phys. Chem. Glas. 2013, 54, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Czapik, P. Microstructure and Degradation of Mortar Containing Waste Glass Aggregate as Evaluated by Various Microscopic Techniques. Materials 2020, 13, 2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollpracht, A.; Lothenbach, B.; Snellings, R.; Haufe, J. The pore solution of blended cements: A review. Mater. Struct. 2016, 49, 3341–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayan, A.; Xu, A. Value-added utilisation of waste glass in concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004, 34, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraghechi, H.; Shafaatian, S.-M.-H.; Fischer, G.; Rajabipour, F. The role of residual cracks on alkali silica reactivity of recycled glass aggregates. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2012, 34, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mass, A.J.; Ideker, J.H.; Juenger, M.C.G. Alkali silica reactivity of agglomerated silica fume. Cem. Concr. Res. 2007, 37, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C441/C441M; Standard Test Method for Effectiveness of Pozzolans or Ground Blast-Furnace Slag in Preventing Excessive Expansion of Concrete Due to the Alkali-Silica Reaction. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- Owsiak, Z.; Czapik, P.; Zapała-Sławeta, J.; Leks, A. Possibility of assessing cements with non-clinker constituents in terms of alkali reactivity with silica aggregate. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2025, 71, 607–617. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdowski, W. Podstawy Chemiczne Mineralnych Materiałów Budowlanych i Ich Właściwości; Polski Cement: Kraków, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Neville, A.M. Properties of Concrete, 5th ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, R.A.; Fazlizan, A.; Asim, N.; Thongtha, A. A Review on the Utilization of Waste Material for Autoclaved Aerated Concrete Production. J. Renew. Mater. 2021, 9, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borek, K.; Czapik, P. Utilization of Waste Glass in Autoclaved Silica–Lime Materials. Materials 2022, 15, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borek, K.; Czapik, P.; Dachowski, R. Recycled Glass as a Substitute for Quartz Sand in Silicate Products. Materials 2020, 13, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahi, S.; Leklou, N.; Khelidj, A.; Ouddjit, M.N.; Zenati, A. Properties of cement pastes and mortars containing green glass powder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 262, 120875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, A.; Younsi, A.; Hamami, A.E.A.; Bastidas-Arteaga, E. Effect of recycled waste glass color on the propertiwes of high-volume glass powder cement pastes. Results Eng. 2025, 28, 107910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 29581-2:2010; Cement—Test Methods—Part 2: Chemical Analysis by X-Ray Fluorescence. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- PN-EN 196-2:2013-11; Metody Badania Cementu—Część 2: Analiza Chemiczna Cementu. Polish Committee for Standarization: Warsaw, Poland, 2013.

- Borek, K. Lime-silica product based on waste packing glass. Constr. Optim. Energy Potential 2024, 13, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Zubaidi, A.B.; Al-Tabbakh, A.A. Recycling Glass Powder and its use as Cement Mortar applications. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2016, 7, 555–564. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, J.M.; Letelier, V.; Solas, C.; Miró, M.; Moriconi, G.; Climent, M.Á.; Sánchez, I. Influence of Waste Glass Powder Addition on the Pore Structure and Service Properties of Cement Mortars. Sustainability 2018, 10, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski, W.; Genevois, C.; Veron, E.; Allix, M. Experimental evidence concerning the significant information depth of X-ray diffraction (XRD) in the Bragg-Brentano configuration. Powder Diffr. 2023, 38, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogirigbo, O. Influence of Slag Composition and Temperature on the Hydration and Performance of Slag Blends in Chloride Environments. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Czapik, P. The Impact of Ions Contained in Concrete Pore Solutions on Natural Zeolites. Materials 2023, 16, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.; Meawad, A. Assessment of waste packaging glass bottles as supplementary cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 182, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Fami, N.E.; Ez-zaki, H.; Diouri, A.; Sassi, O.; Boukhari, A. Improvement of hydraulic and mechanical properties of dicalcium silicate by alkaline activation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 247, 118589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbev, K.; Gasharova, B.; Beuchle, G.; Kreisz, S.; Stemmermann, P. First Observation of α-Ca2[SiO3(OH)](OH)–Ca6[Si2O7][SiO4](OH)2 Phase Transformation upon Thermal Treatment in Air. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2008, 91, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Shen, J.; Yang, R.; Ji, H.; Ding, J. Effect of Curing Age on the Microstructure and Hydration Behavior of Oil Well Cement Paste Cured at High Temperature. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2021, 33, 04021006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, M.M. Crystallization of Synthetic Wollastonite Prepared from Local Raw Materials. Int. J. Mater. Chem. 2014, 4, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Mohsen, A.; Aiad, I.; El-Hossiny, F.I.; Habib, A.O. Evaluating the Mechanical Properties of Admixed Blended Cement Pastes and Estimating its Kinetics of Hydration by Different Techniques. Egypt. J. Pet. 2020, 2, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrowski, A.; Gawliczki, M.; Łagosz, A.; Nocuń-Wczelik, W. Cement: Metody Badań, Wybrane Kieunki Stosowania; AGH: Krakow, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri, A.; Rad, M.S.K.; Goodarznia, I. Experimental investigation of nano-boric acid effects as retarding agent on physical/chemical properties of cement slurries for high-pressure high-temperature oil and gas wells. Int. J. Pet. Geosci. Eng. 2021, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Nocuń-Wczelik, W.; Czapik, P. Use of calorimetry and other methods in the studies of water reducers and set retarders interaction with hydrating cement paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 38, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Oxide Glass | Colorless | Brown | Green |

|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 72.53 | 71.56 | 72.11 |

| Na2O | 13.03 | 13.13 | 13.15 |

| CaO | 10.53 | 10.28 | 10.01 |

| Al2O3 | 1.93 | 1.72 | 1.73 |

| MgO | 1.19 | 2.14 | 1.44 |

| K2O | 0.36 | 0.47 | 0.57 |

| SO3 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Fe2O3 | 0.08 | 0.41 | 0.43 |

| TiO2 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.14 |

| SrO | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| ZrO2 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| P2O5 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Mn2O3 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| Cr2O3 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.25 |

| Time Phase | 1 h | 7 d | 28 d | 56 d | 330 d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| calcite | |||||

| portlandite | - | ||||

| - | |||||

| - | |||||

| thermonatrite | - | - | - | ||

| - | - | - | |||

| - | - | - | |||

| tobermorite | - | - | |||

| - | - | ||||

| - | - | - | |||

| dellaite | - | - | - | - | |

| - | - | - | - | ||

| - | - | - | - | ||

| wollastonite | - | - | - | - | |

| - | - | - | - | ||

| - | - | - | - | ||

| saponite | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | ||

| - | - | - | - | - | |

| The presence of the phase in the sample: | |||||

| colorless glass | brown glass | green glass | |||

| No | Temperature Range [°C] | Maximum [°C] | Loss for Colorless Glass [%] | Loss for Brown Glass [%] | Loss for Green Glass [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50–100 | 98 | 0.767 | 0.848 | 0.557 |

| 2 | 100–150 | 125 | 1.162 | 0.768 | 0.624 |

| 3 | 150–200 | 180 | 0.740 | 1.525 | 1.572 |

| 2 + 3 | 100–200 | - | 1.902 | 2.293 | 2.196 |

| 1 + 2 + 3 | 50–200 | - | 2.669 | 3.097 | 2.753 |

| 4 | 400–470 | 440 | 0.578 | 0.498 | 0.562 |

| Calculated Ca(OH)2 | 2.375 | 2.049 | 2.309 | ||

| 5 | 480-630 | 610 | 3.659 | 3.491 | 2.479 |

| 6 | 630-770 | 705 | 6.123 | 7.034 | 8.105 |

| Calculated CaCO3 | 13.925 | 15.997 | 18.433 | ||

| Amount of Ca(OH)2 needed to form CaCO3 | 10.309 | 11.843 | 13.646 | ||

| 5 + 6 | 480–770 | - | 9.782 | 10.525 | 10.584 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Czapik, P.; Borek, K. Transformation of Waste Glasses in Hydroxide Solution. Materials 2025, 18, 5565. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245565

Czapik P, Borek K. Transformation of Waste Glasses in Hydroxide Solution. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5565. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245565

Chicago/Turabian StyleCzapik, Przemysław, and Katarzyna Borek. 2025. "Transformation of Waste Glasses in Hydroxide Solution" Materials 18, no. 24: 5565. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245565

APA StyleCzapik, P., & Borek, K. (2025). Transformation of Waste Glasses in Hydroxide Solution. Materials, 18(24), 5565. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245565