Identification of Key Factors Governing Compressive Strength in Cement-Stabilized Rammed Earth: A Controlled Assessment of Soil Powdering Prior to Mixing

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

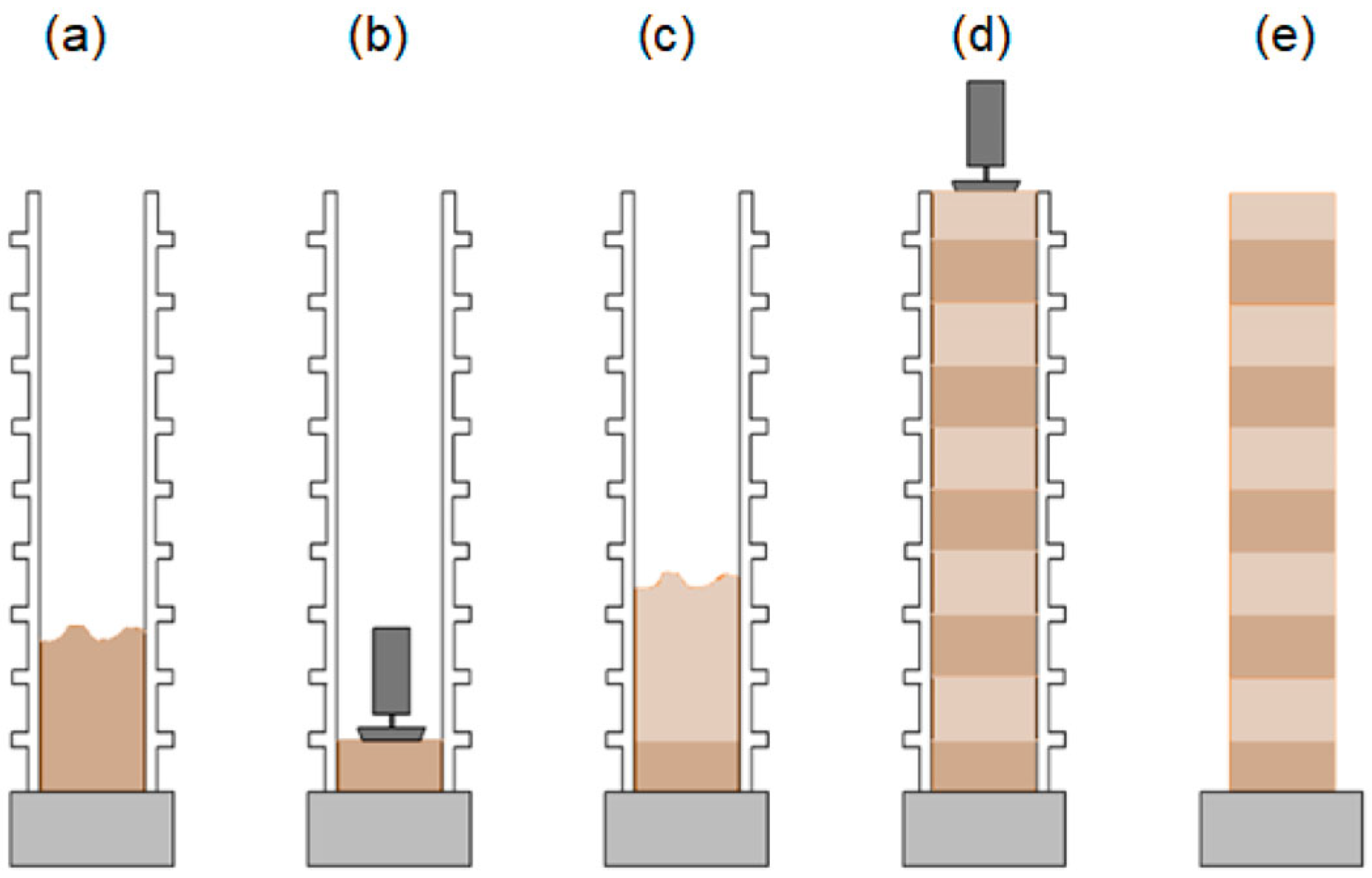

1.2. Construction Method

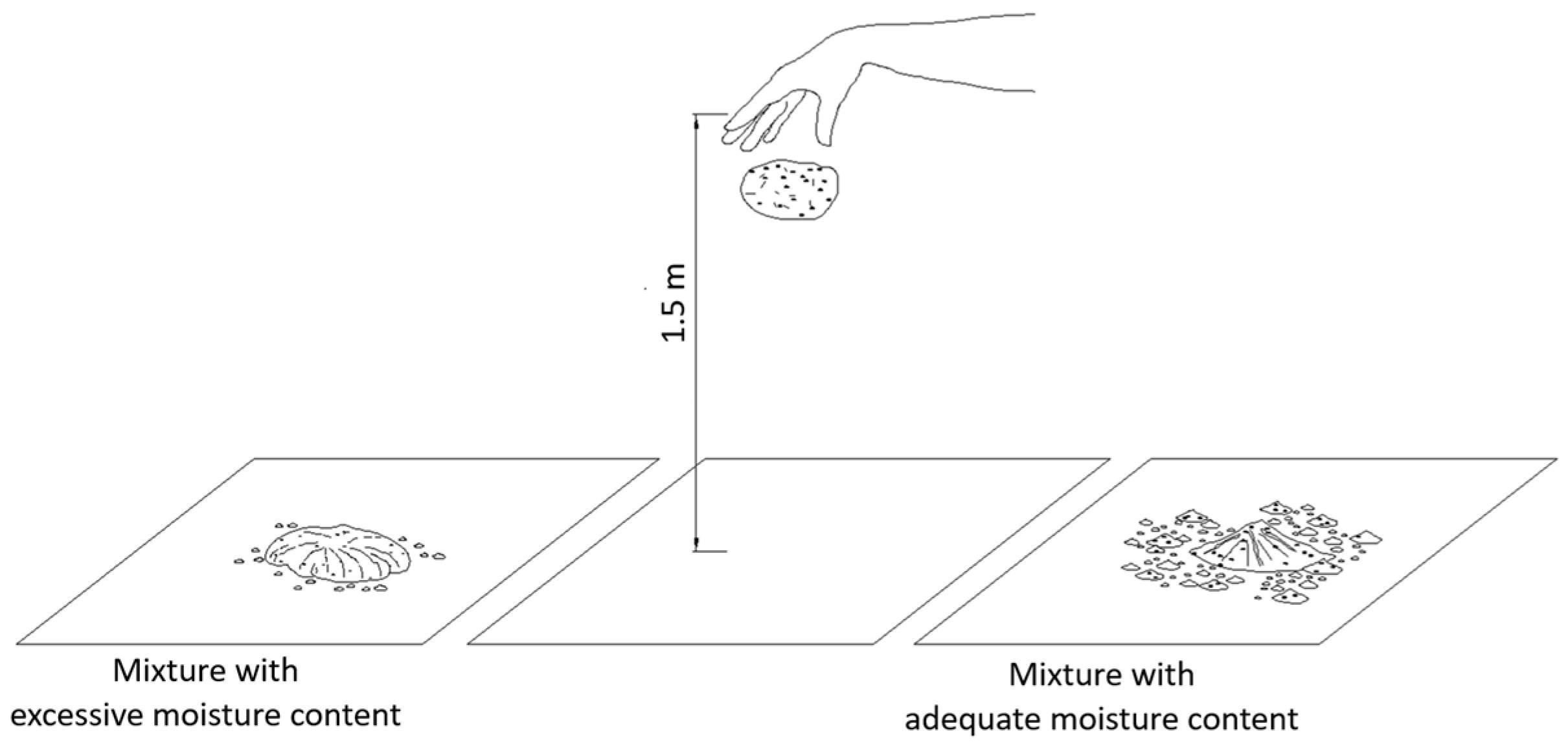

1.3. Empirical Field Method for Estimating Suitable Moisture Content

1.4. Compressive Strength Studies

| Ref. | Sample Geometry | Compaction Method | Binder Type & Content | Moisture Content | Curing Conditions | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Soil Processing Description | Soil Condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [15] | Cubes (100 × 100 × 100 mm) | Mechanical ramming | Cement (3–10%) | 6–14% | 28 days at ambient conditions | 2.4–13.0 | Soil sieved and blended with sand and gravel to achieve desired granulometry. | mechanically processed soil |

| [16] | Cubes and cored cylinders | Mechanical ramming | Cement (10–20%) | Optimum moisture content via Proctor test | 120 days at ambient conditions | Varies; strength increases over time | Soil stabilized with cement; specimens cured for extended periods to assess strength development. | no information |

| [17] | Cylinder (Ø150 × 150 mm) | Manual compaction | None; straw fibers (0.1–0.4%) | Moisture content of the raw material 15.33% | 28 days at ambient conditions | Up to 1.5 | Natural red soil mixed with straw fibers of varying lengths and contents. | natural soil |

| [18] | Prisms (40 × 40 × 160 mm) | Mechanical ramming | None | 9.58–9.9% | 28 days at ambient conditions | Approximately 1.5 | Soil sieved and blended with sand to optimize particle size distribution. | mechanically processed soil |

| [19] | Cubes (100 × 100 × 100 mm) | Mechanical ramming | Biopolymers (e.g., xanthan gum) | Not reported in source study | 28 days at ambient conditions | 1.2–2.0 | Natural soil stabilized with biopolymers to enhance cohesion and water resistance. | natural soil |

| [4] | Cubes (100 × 100 × 100 mm) | Mechanical ramming | Cement (6%) | 7–8% | 28 days at ambient conditions | 3.0–5.5 | Soil mineralogy varied; samples included montmorillonite, beidellite, and kaolinite. | no information |

| [20] | Cylinder (Ø150 × 150 mm) | Mechanical compaction | None; reinforced with straw fibers | 8.9% | 28 days at ambient conditions | 0.75–2.88 | Local soil mixed with straw fibers; focus on optimizing workability and mechanical properties. | natural soil |

| [21] | Various (cubes, cylinders) | Manual and mechanical ramming | None and various stabilizers | 0.7 to 12.0% | Varies (up to 90 days) | 1.0–3.5 | Studies conducted on traditional and modern rammed earth structures with varying compositions. | no information |

| [22] | Cylinder (Ø50 × 100 mm) | Mechanical compaction | None | Optimum water content | 28 days at ambient conditions | Approximately 1.0 | Soil compacted at optimum moisture; samples cored from larger Proctor molds. | no information |

| [23] | Not specified | Manual compaction with varying loads (1–3 MPa) | Polymer aqueous solution; cement | 10% and 20% | 1, 3, and 7 days at ambient conditions | 1.7–2.4 | Red soil mixed with polymer aqueous solution and cement; moisture content adjusted to 10% or 20%. | no information |

| [24] | Cube (50 × 50 × 50 mm) | Autonomous mechanical compaction | Epoxy emulsion (6.8%) | Not reported in source study | 3, 6, 12, and 24 h at ambient conditions | Up to 2.4 | Red soil stabilized with epoxy emulsion to enhance early-age strength for automated construction. | no information |

| [25] | Not specified | Mechanical compaction | Liquid polymer (various percentages) | Optimum moisture content via Proctor test | 7 days-open air | Over 13 | Natural soil modified with liquid polymer; optimum moisture content determined for stabilization. | natural soil |

| [26] | Cylinder (dimensions not specified) | Manual or pneumatic ramming | Natural mining by-products | 6.9–21.4% | 7.28 and 90 days ambient condition | 0.6–12.5 | Soil mixtures incorporating mining by-products evaluated for suitability in rammed earth construction. | no information |

| [27] | 40 × 40 × 160 mm | Not reported in source study | Cement (2–8%) | 18% (including the residual moisture content in the soil) | 28 days | 2.0 ± 0.2 (with 2% cement) | Soil stabilized with varying cement contents; compressive strength assessed using rebound hammer test. | no information |

| [28] | Cubes (70.7 mm, 100 mm, 150 mm) and cylinders | Not reported in source study | None | 18.2–23% | 14, 21, and 28 days at ambient conditions | Not reported in source study | Soil passed through a 2-mm sieve to remove debris; uniaxial compression tests conducted to develop constitutive equations. | no information |

| [29] | Not specified | Mechanical compaction | Natural stabilizers (e.g., agricultural by-products) | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Soil mixed with local waste and recycled materials to enhance mechanical strength without compromising recyclability. | no information |

| [30] | Blocks (10 cm (depth) × 20 cm (length) × 30 cm (height)) | Manual compaction | None | Controlled moisture content 14.0% | Not reported in source study | 0.9–4.17 | Soil compacted using historical techniques; study highlights variability in compressive strength across different wall regions. | no information |

| [31] | Small cylinders (diameter 10.1cm, height 11.5cm) Prisms (50 × 50 × 10 cm) | Mechanical compaction | None | Optimum moisture content 13% | Not reported in source study | 1.36–1.4 | Unstabilized soil compacted into prismatic samples; mechanical properties assessed through experimental and numerical methods. | no information |

| [32] | Cubes (150 mm) | Mechanical compaction | Metakaolin (various percentages) | Determined via compaction tests | 7, 14, and 28 days at ambient conditions | 0.3–1.2 | Soil stabilized with metakaolin; compressive strength evaluated over different curing periods. | no information |

| [33] | Not specified | Not specified | Various chemical stabilisers and fibres cement contents of 7% and 10% along with 0.5%, 1%, 1.5% and 2% fibre content | Not reported in source study | 28 days | Highest value 6.87 | Comprehensive review of chemical stabilisation and fibre reinforcement methods to improve mechanical properties of rammed earth. | no information |

| [34] | Cylinder for UCS (39.1 (diameter × 80 height, mm) | static compaction method per ASTM D 2166 | Varied clay contents | optimum moisture Content via Proctor test | Ambient conditions in the laboratory 28 days | 0.73–1.35 | Study on how varying soil content affects the engineering properties of unstabilized rammed earth. | no information |

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

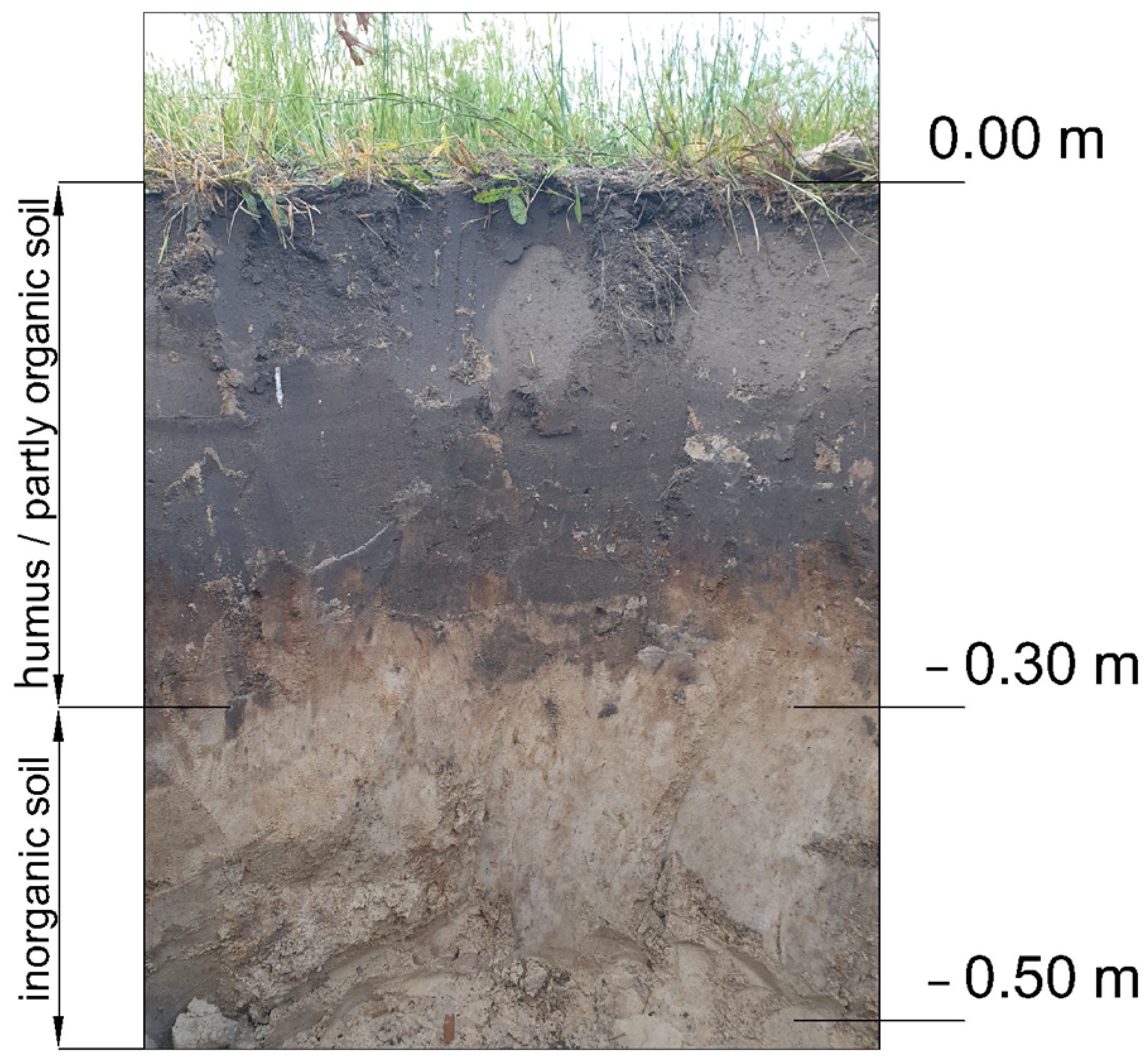

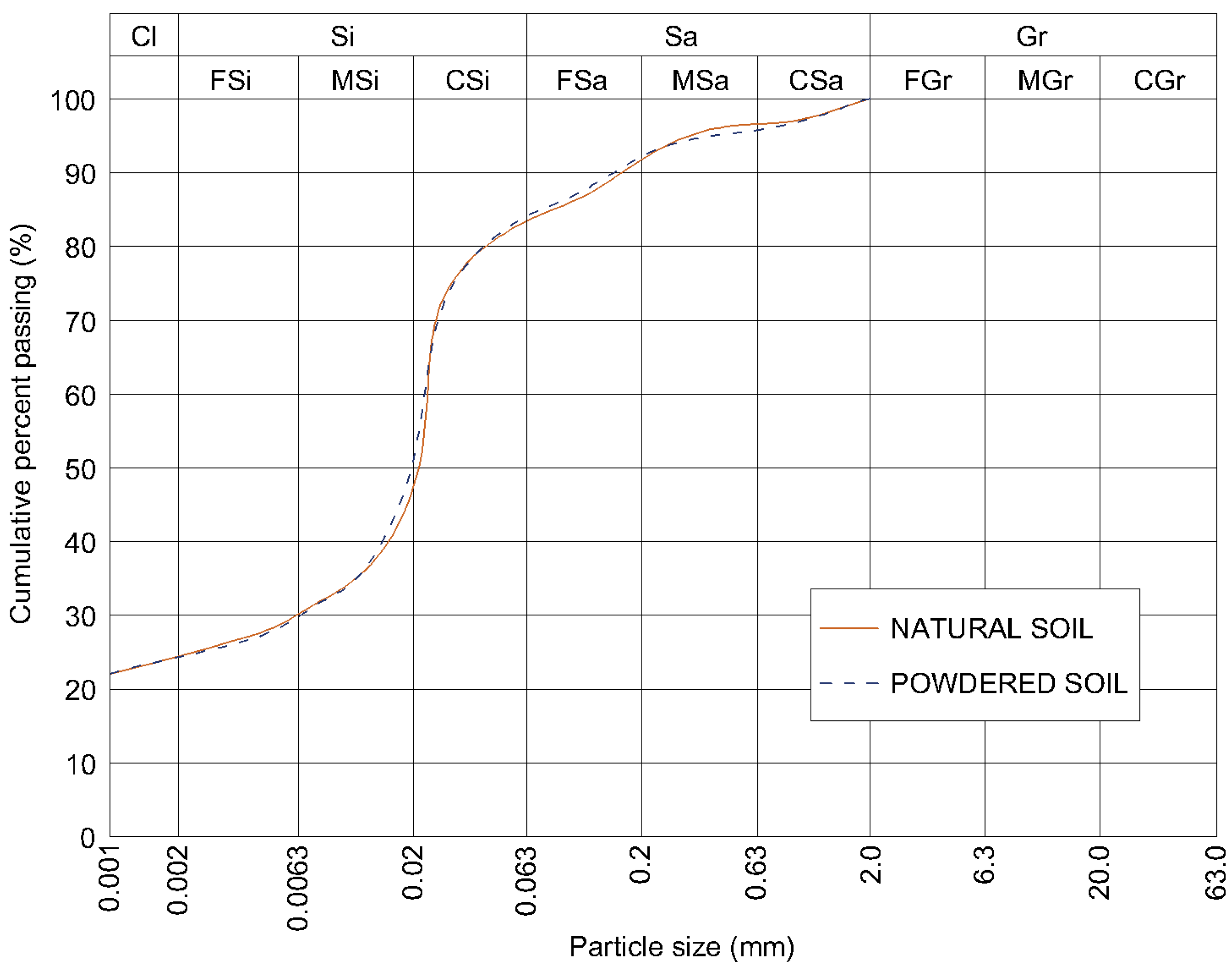

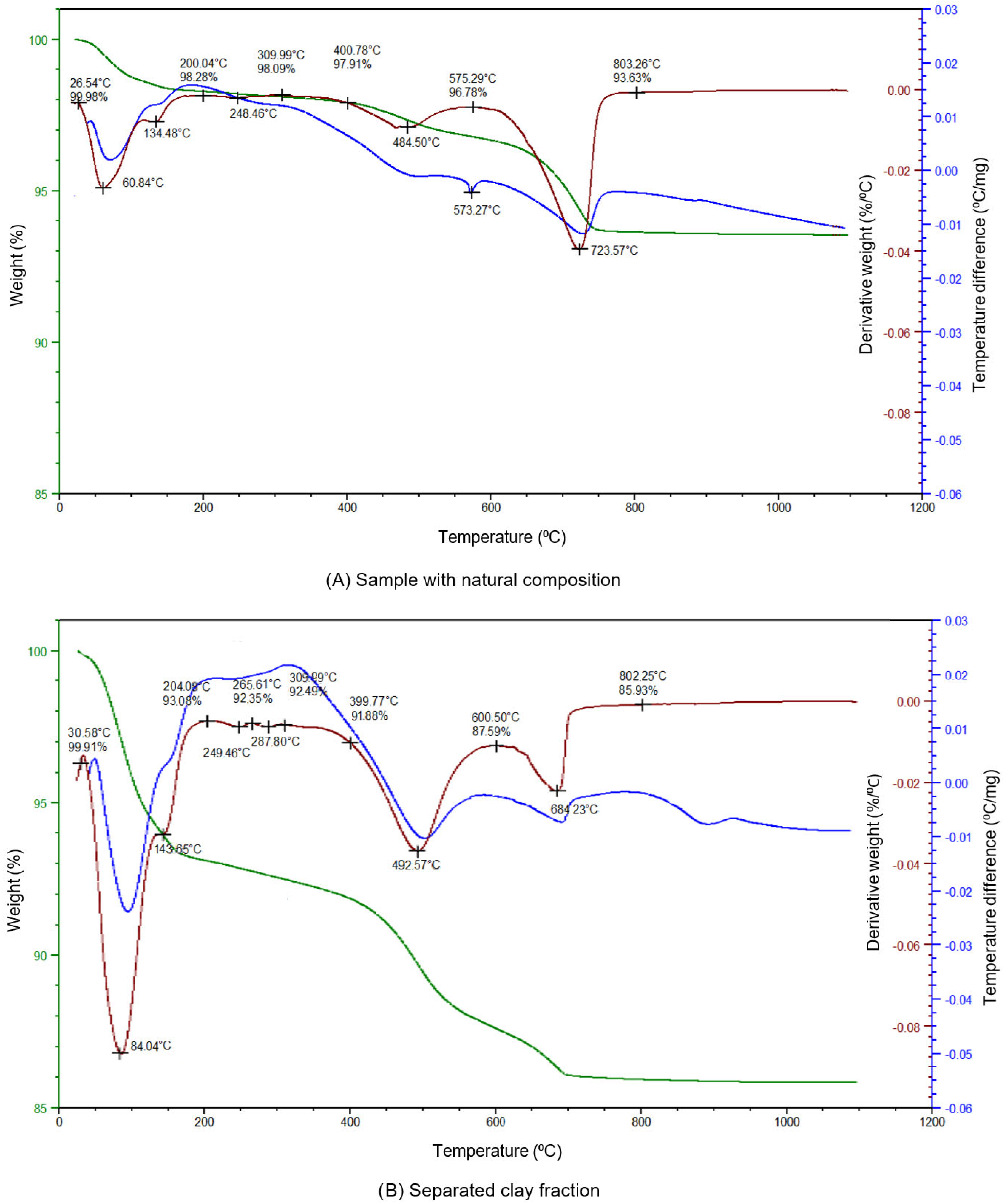

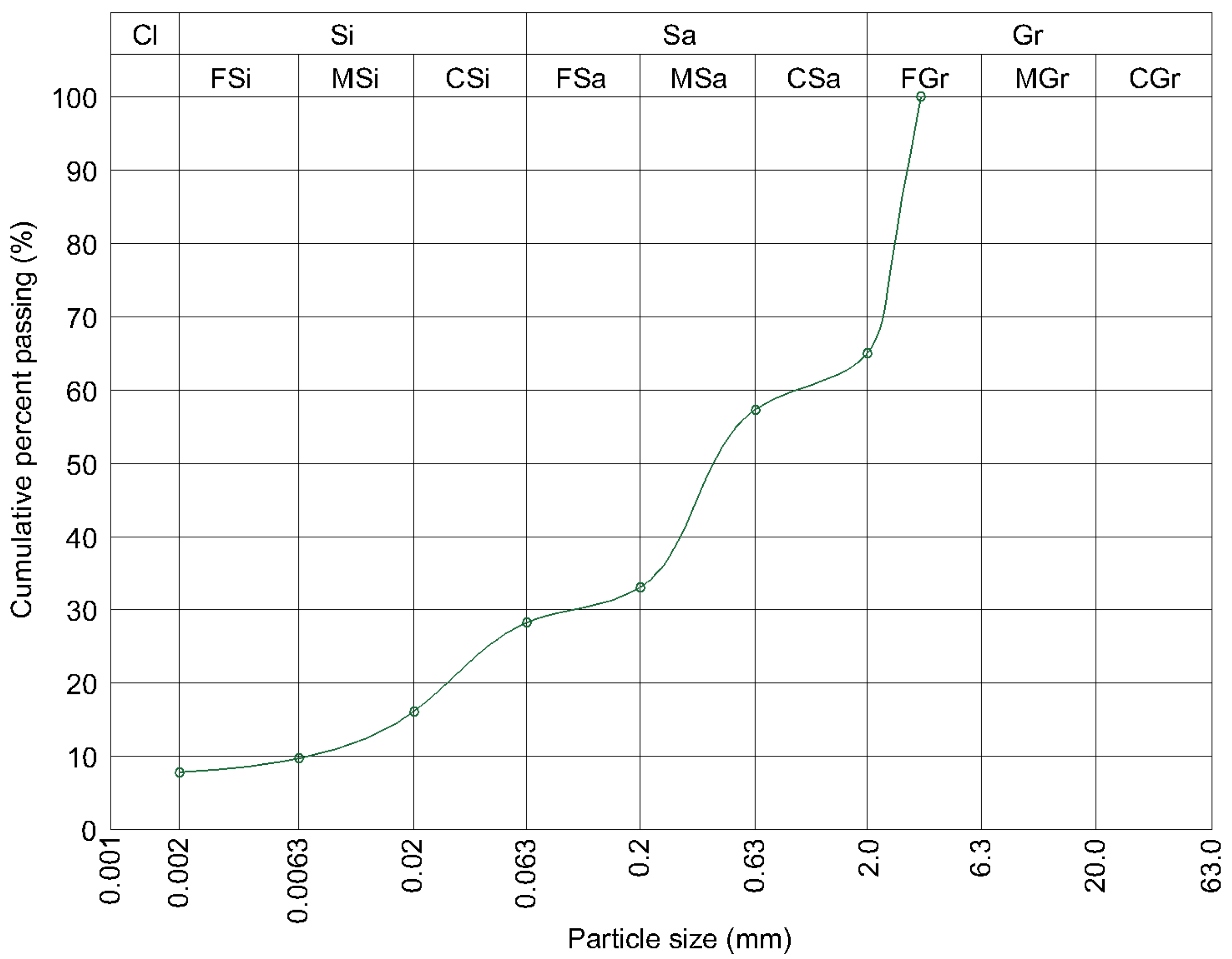

2.1.1. Soils Used in the Study

2.1.2. Rammed Earth Mix Design

2.2. Methods

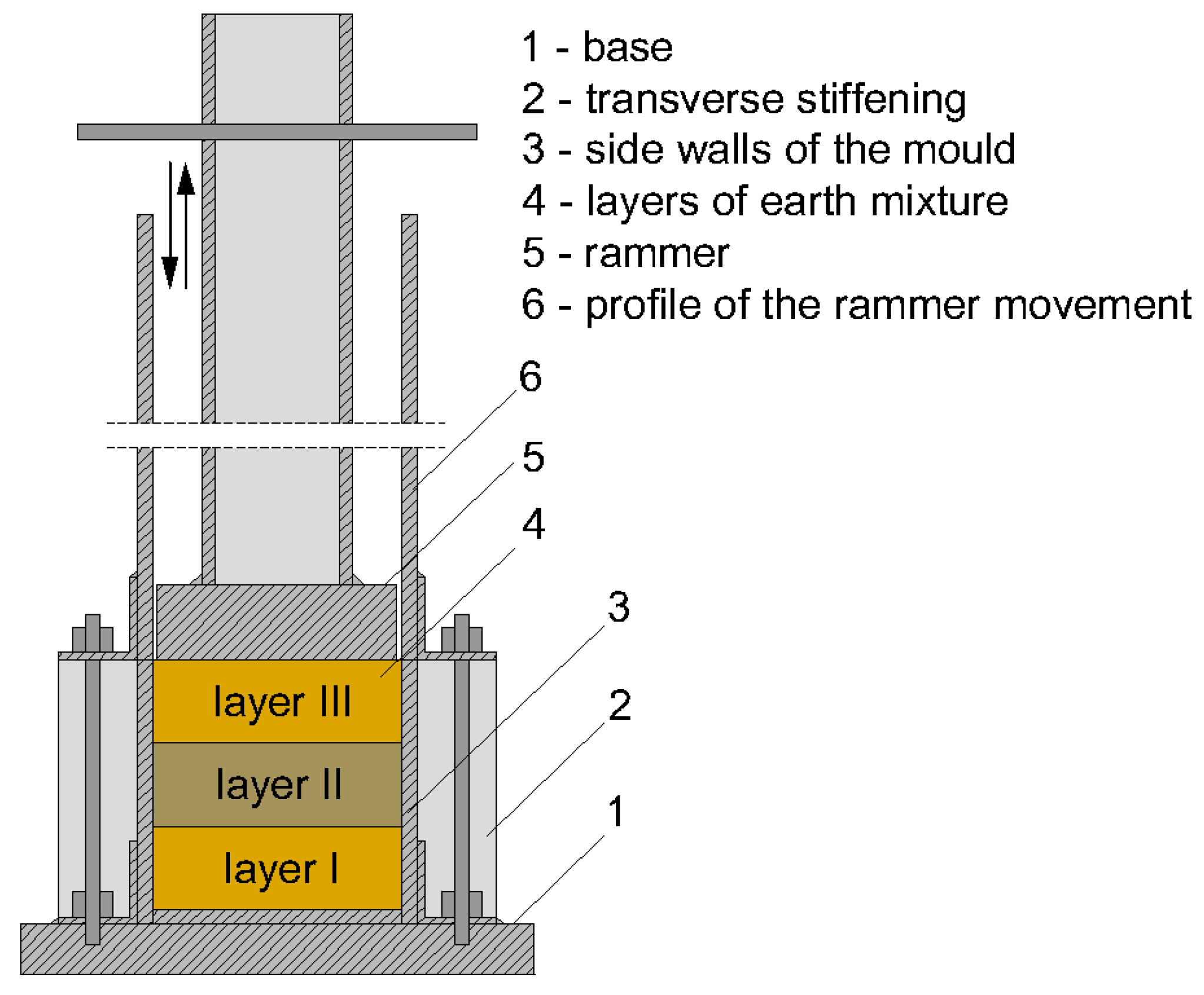

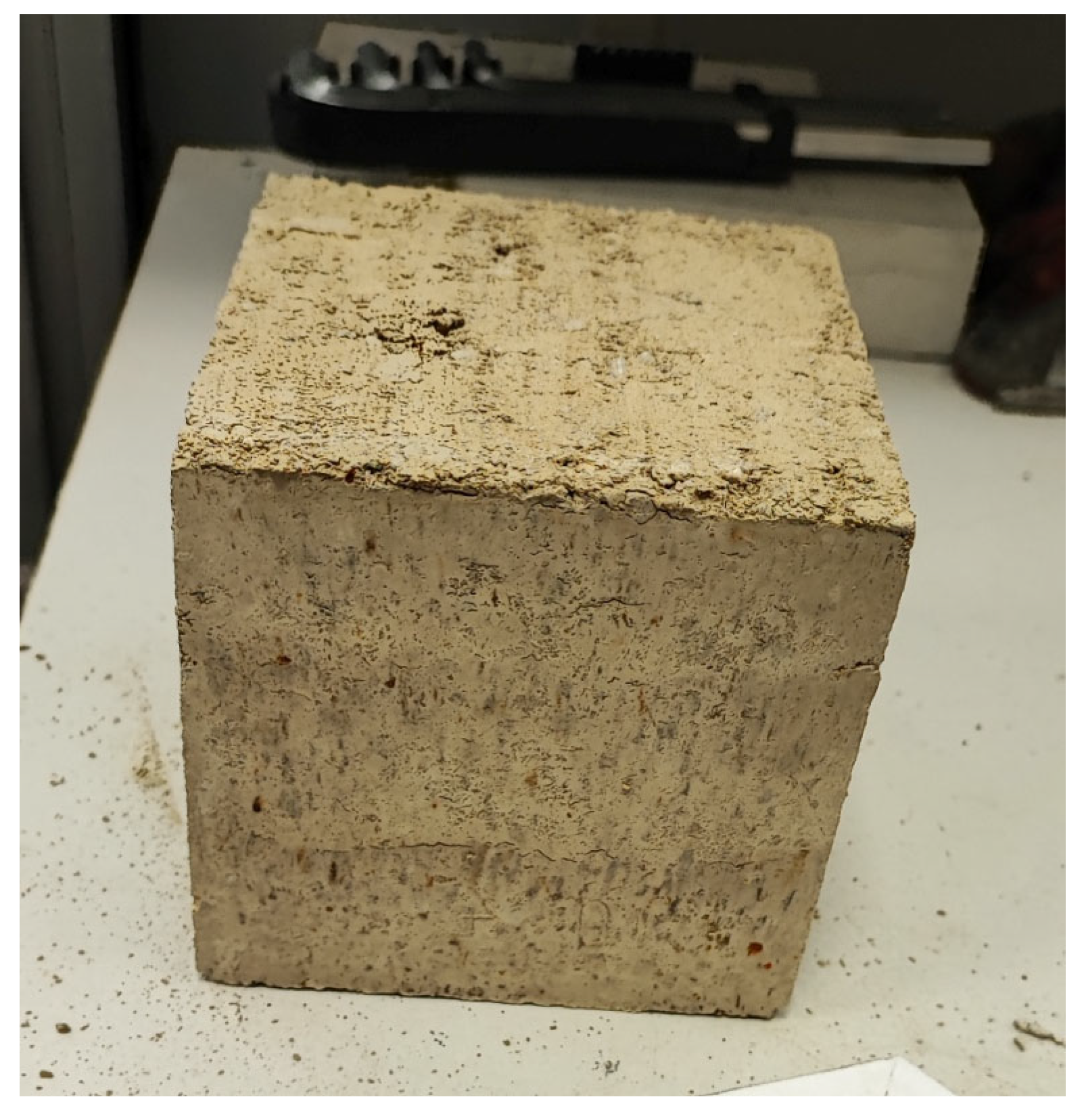

2.2.1. Specimen Preparation

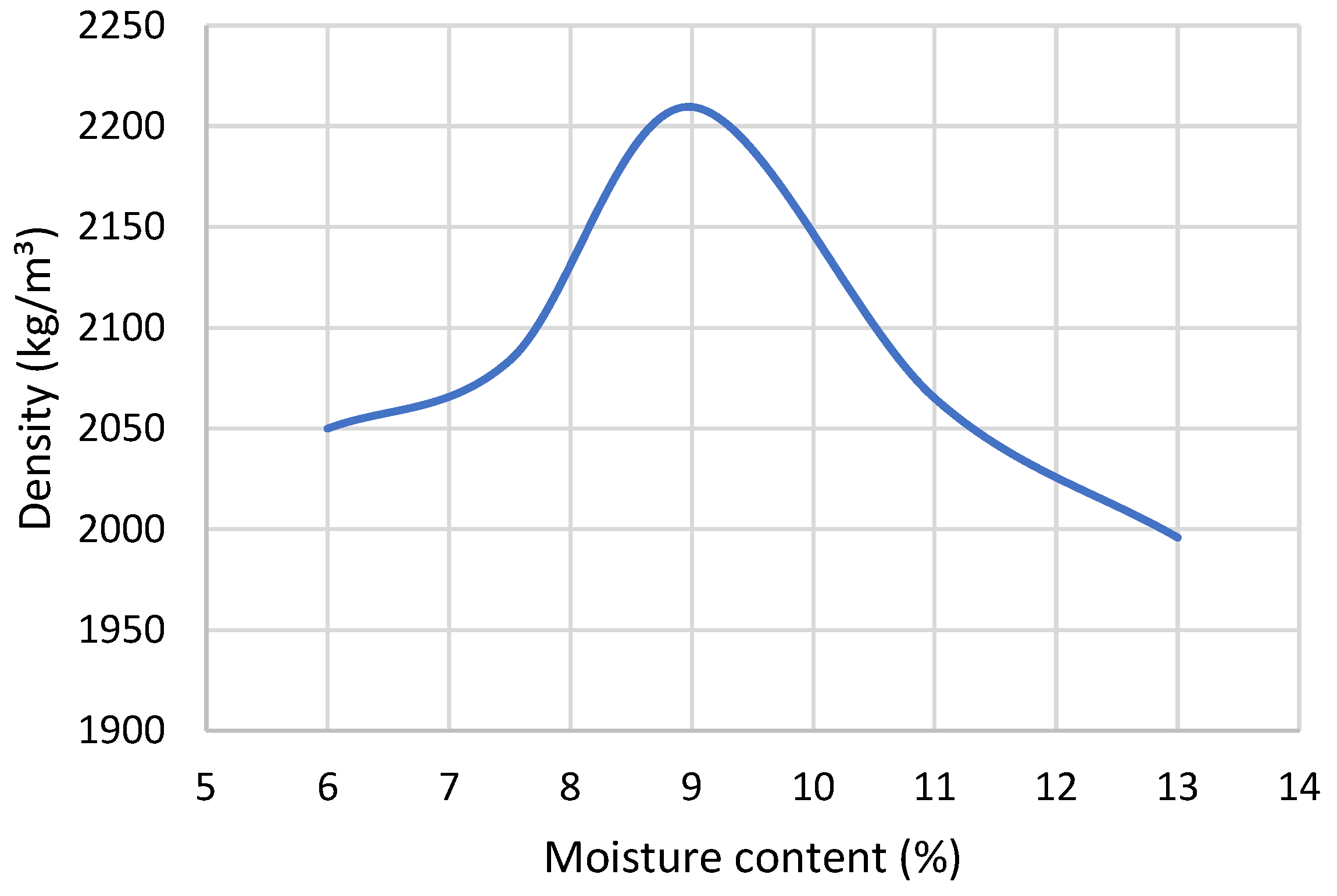

2.2.2. Optimum Moisture Content of the CSRE Mixture

2.2.3. Ball Drop Test for CSRE

2.2.4. Compressive Strength Test

2.2.5. Theoretical Background on Statistical Methods Used

3. Results

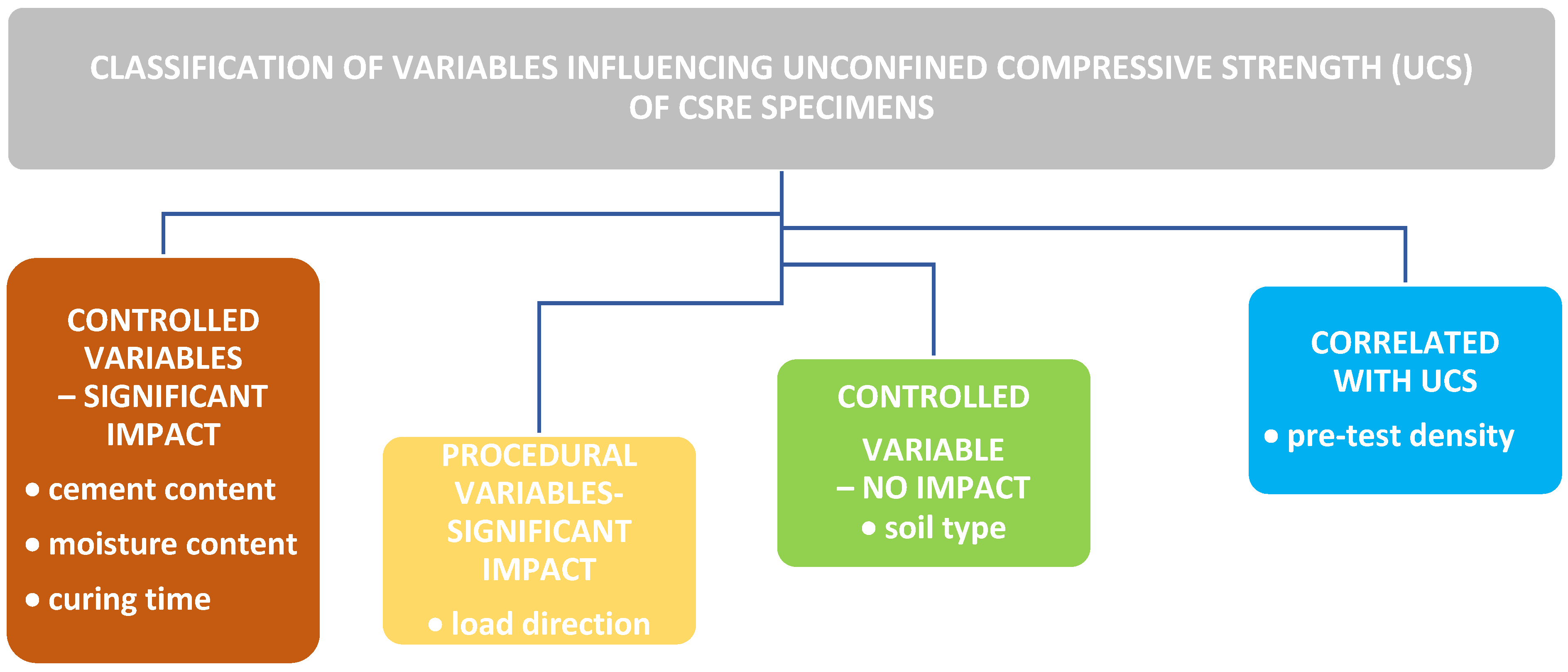

4. Results Analysis

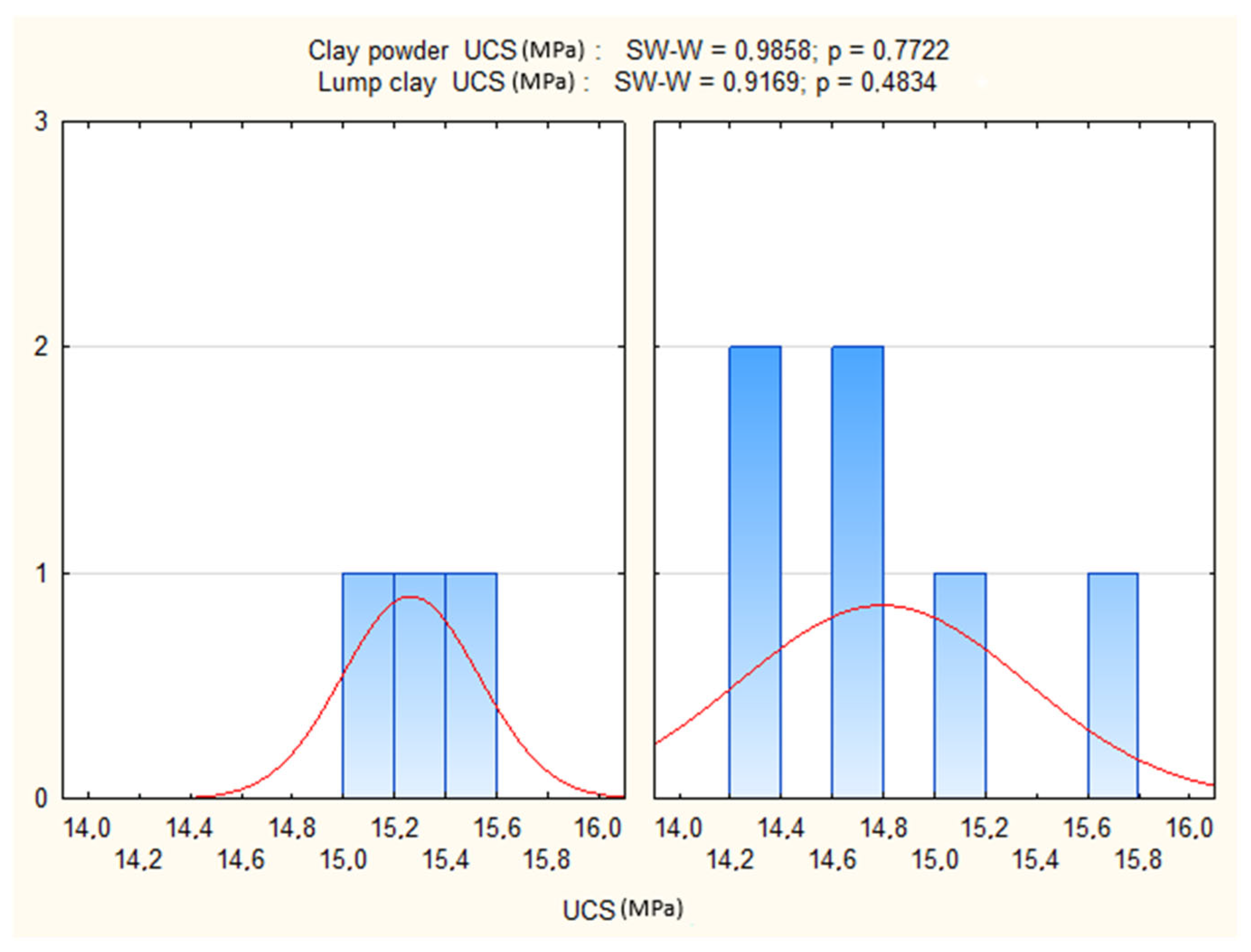

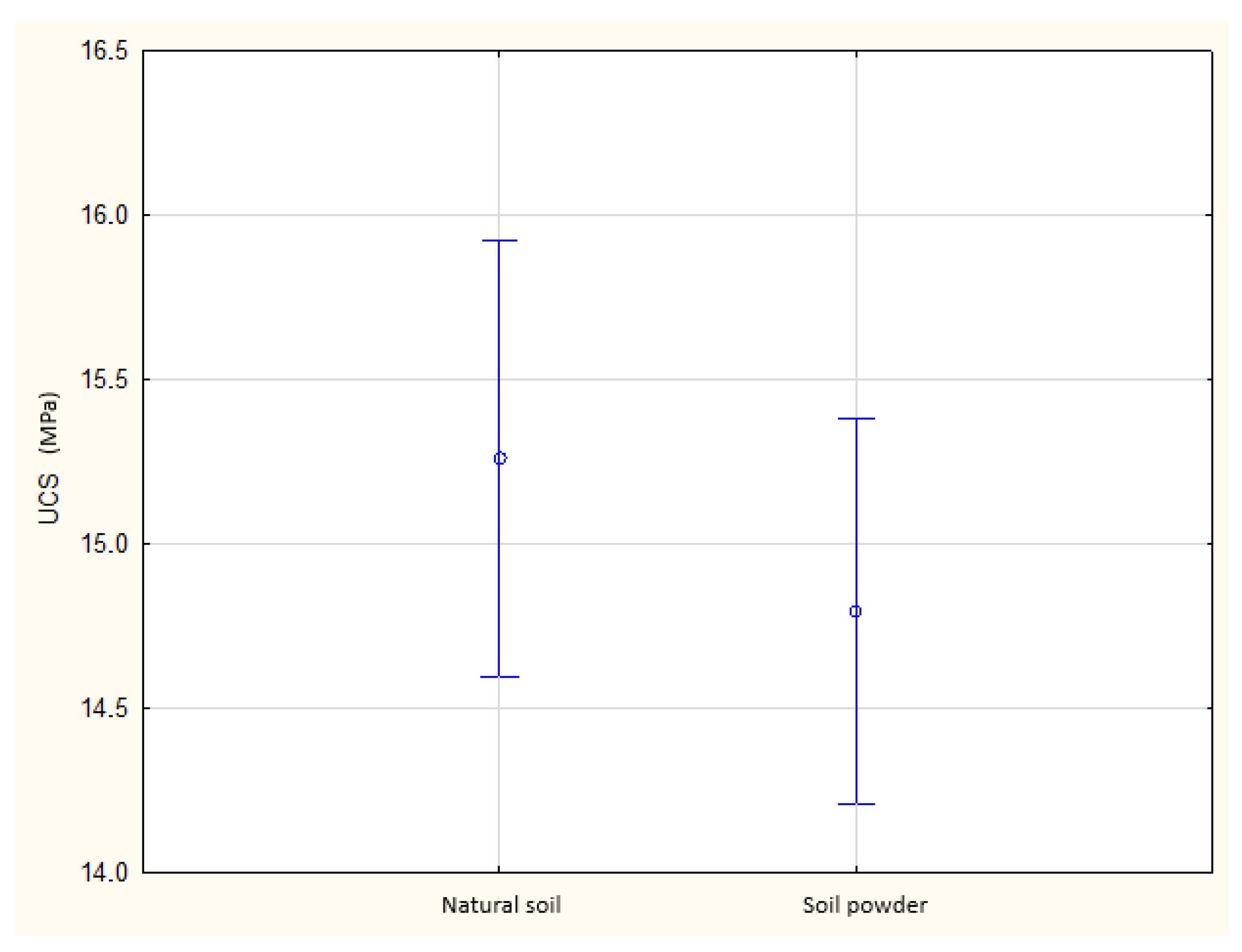

4.1. Effect of Soil Type

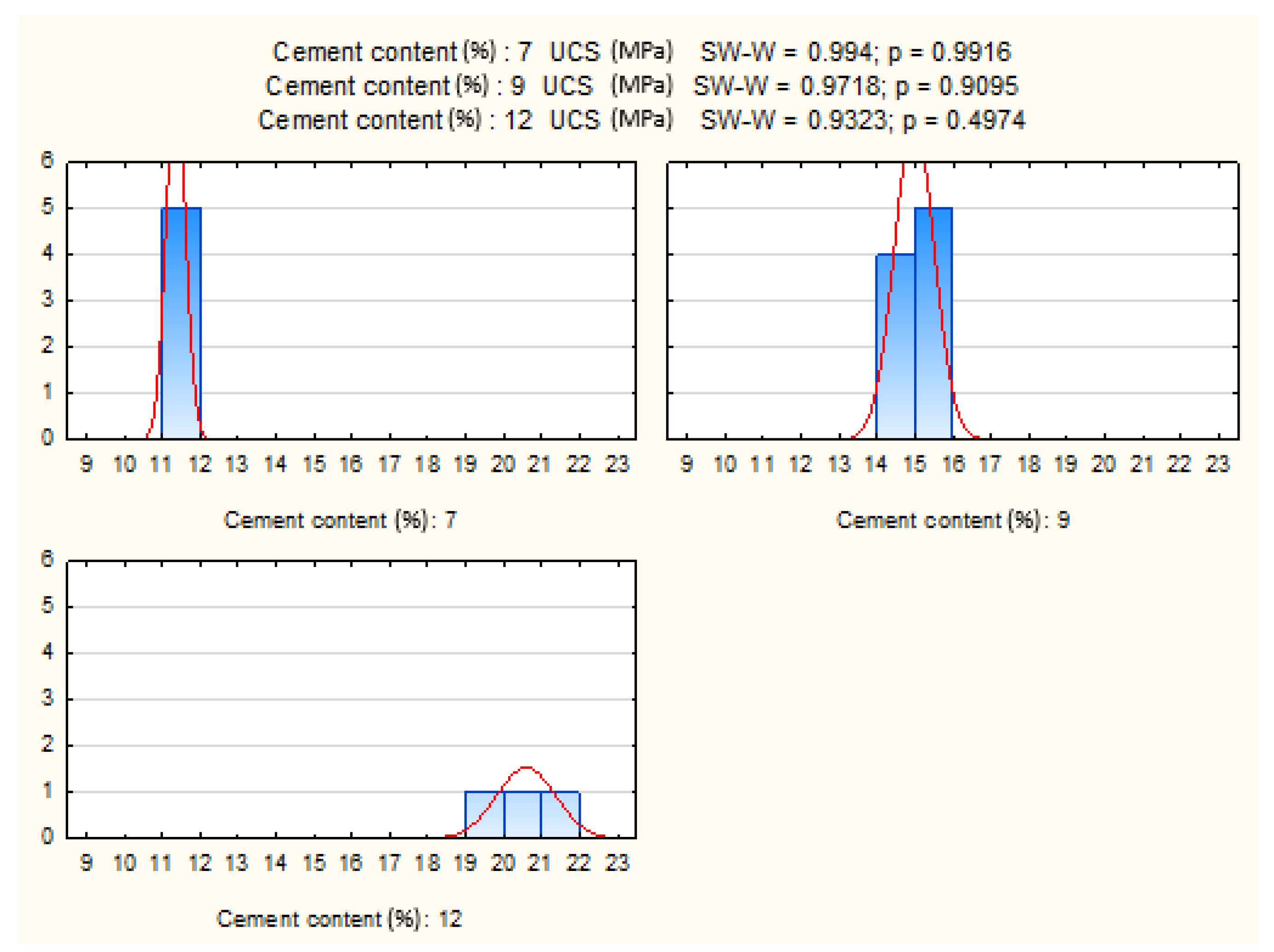

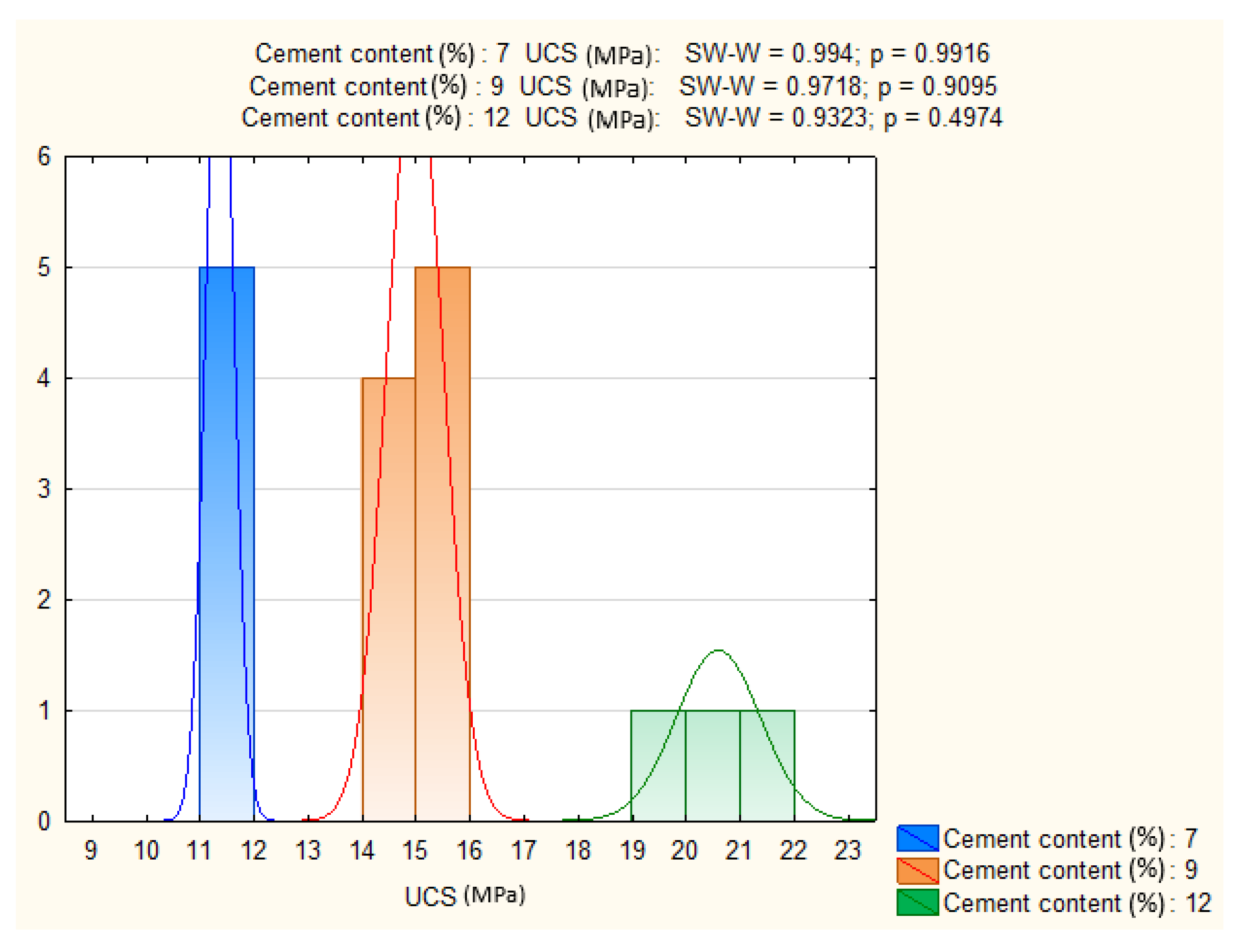

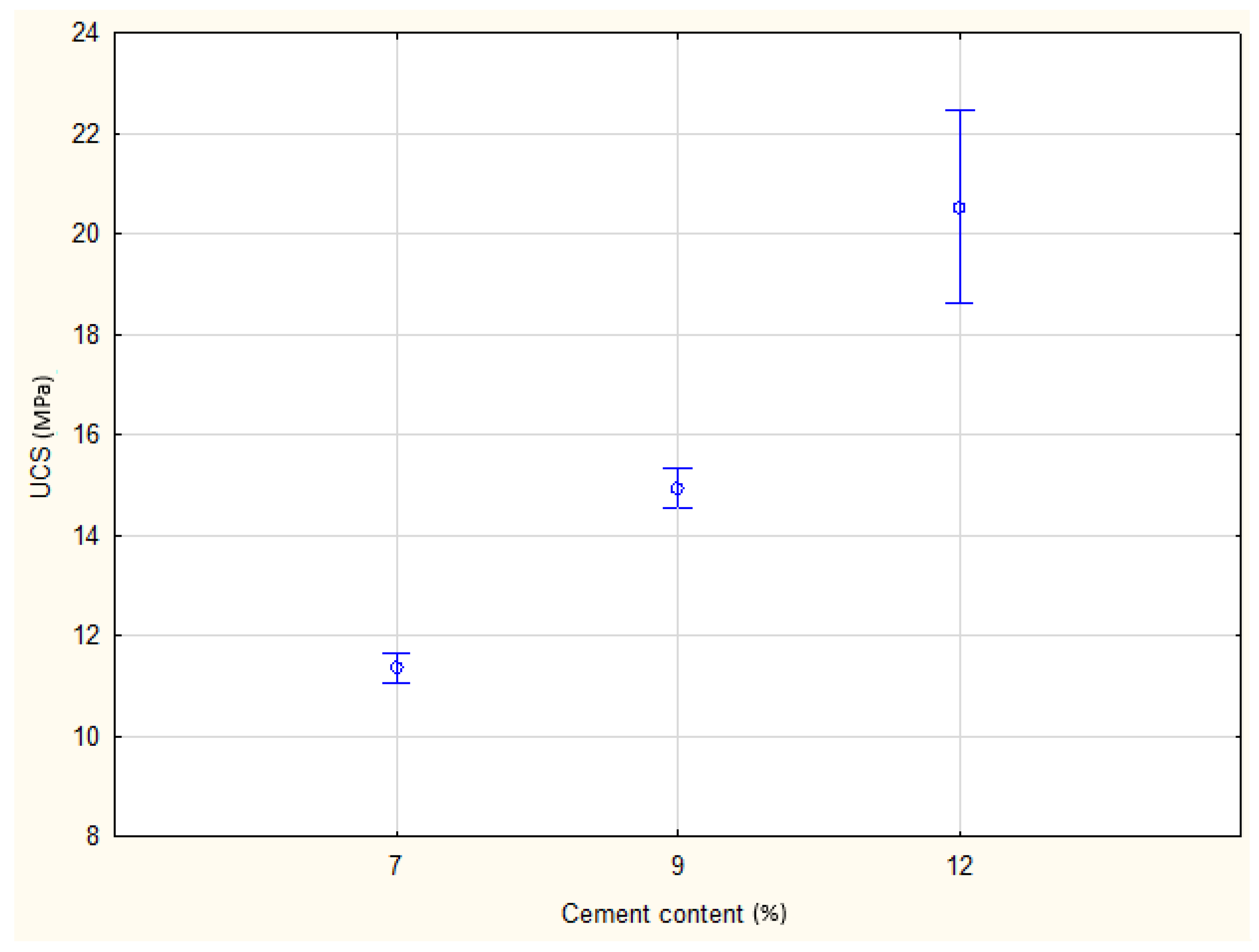

4.2. Effect of Cement Content

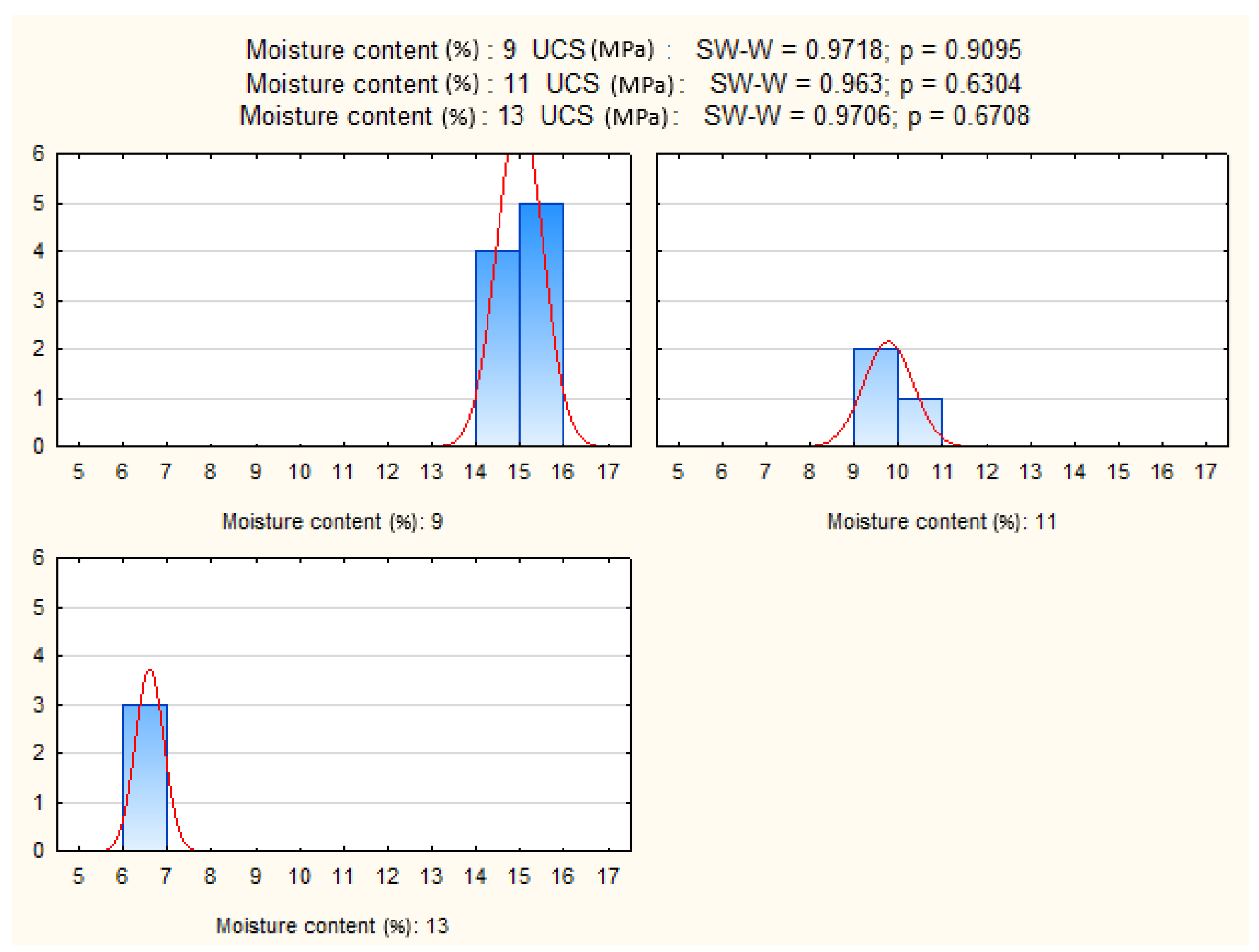

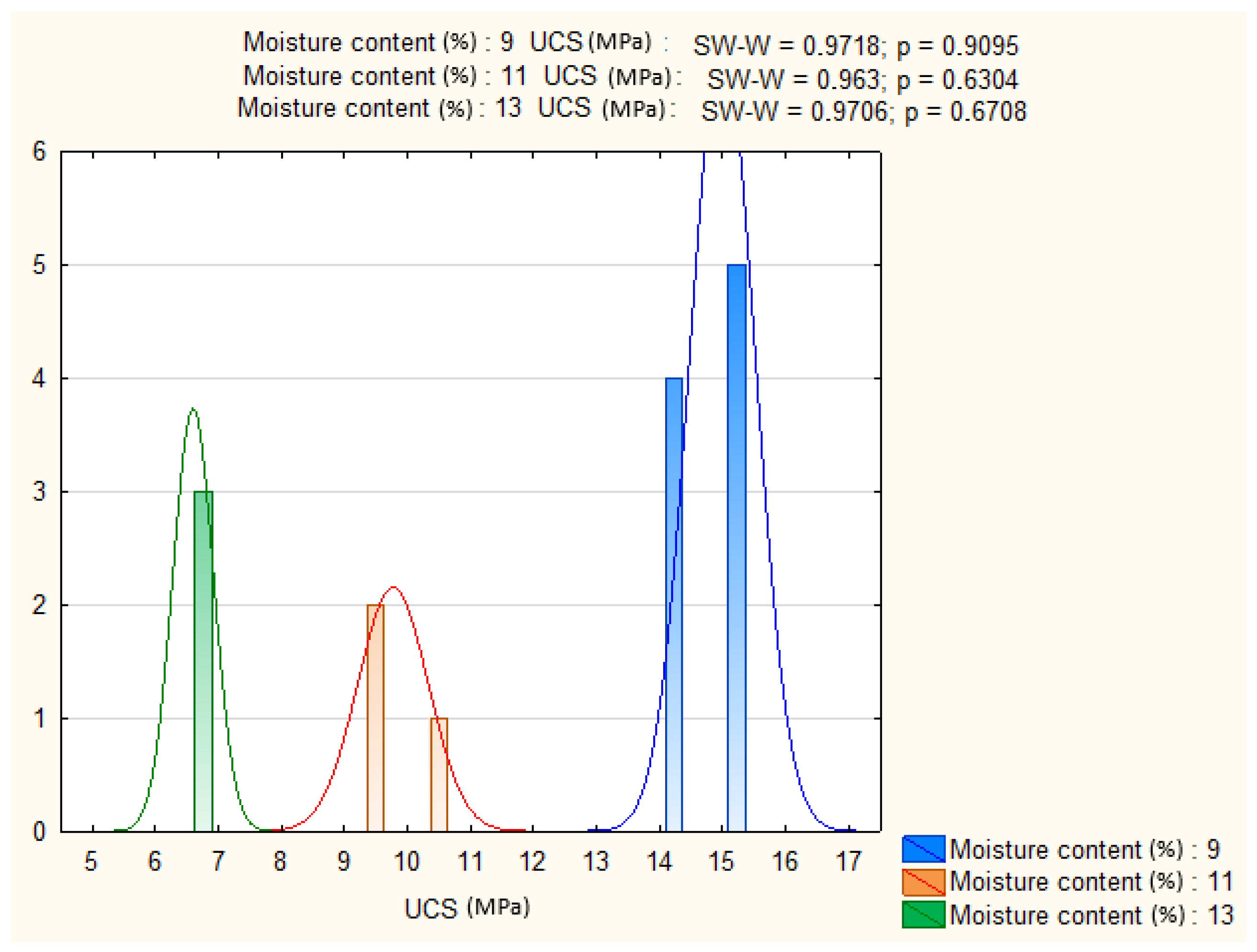

4.3. Effect of Moisture Content

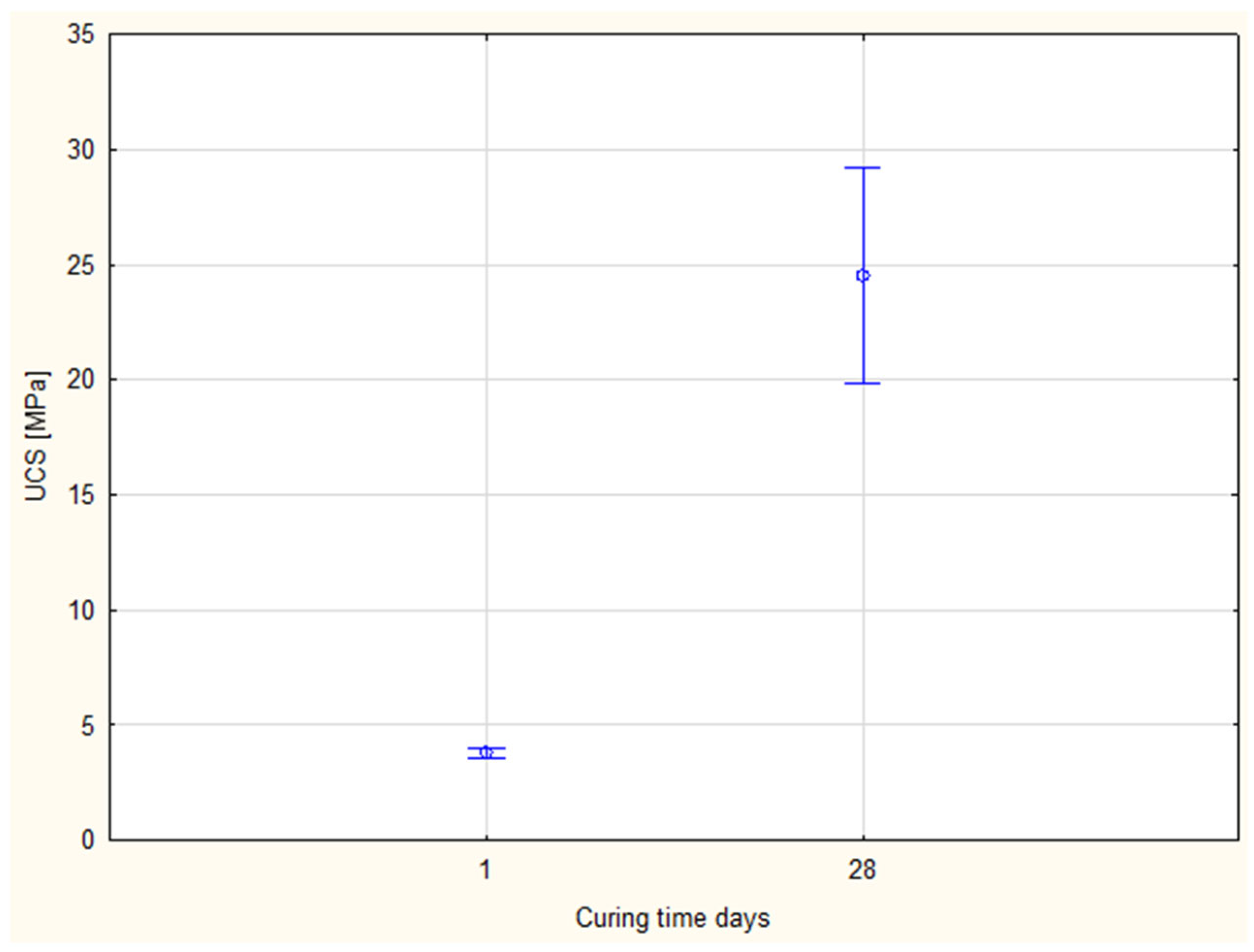

4.4. Effect of Curing Time

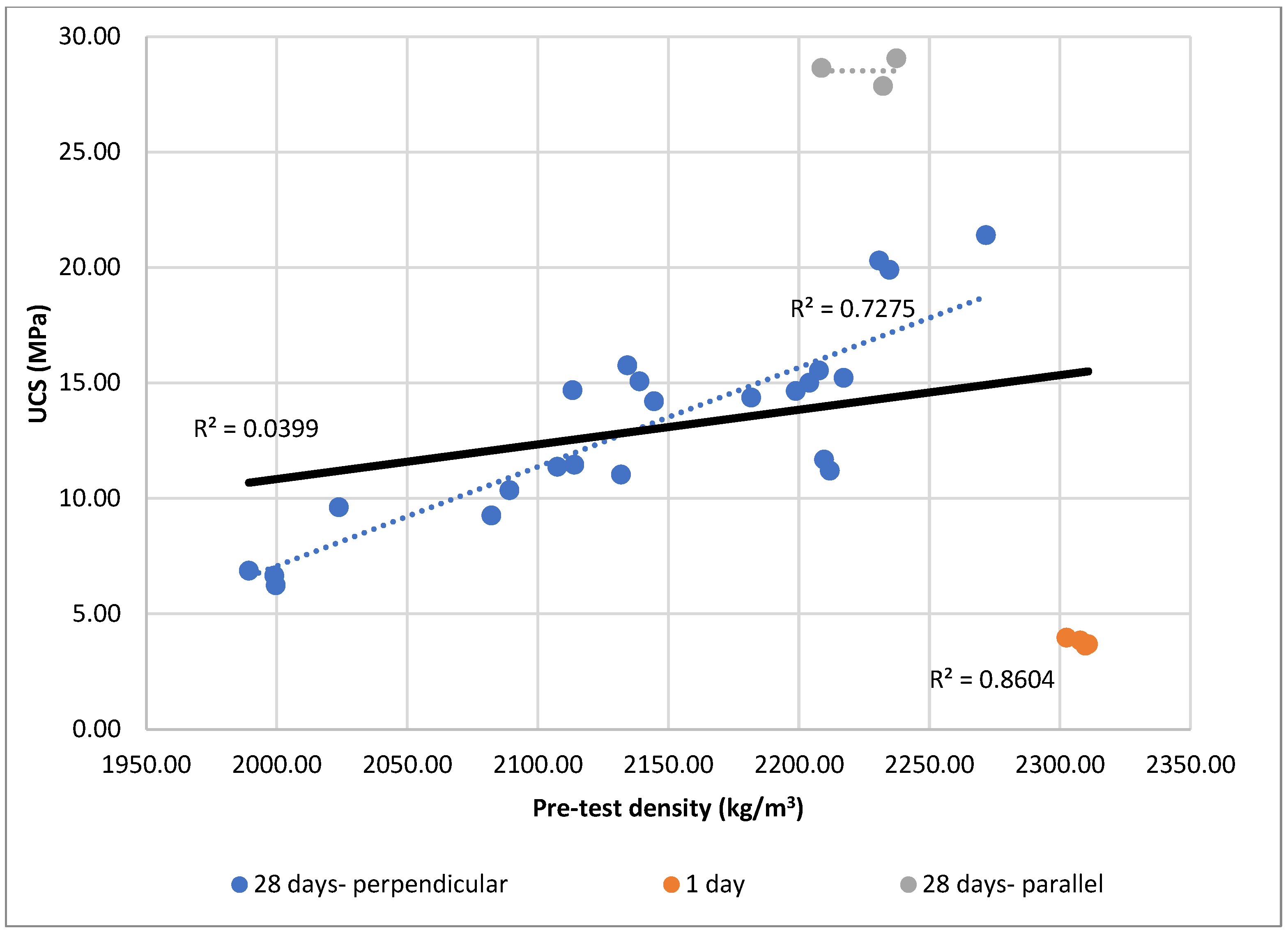

4.5. Correlation Analysis of Physical Parameters

4.6. Effect of Loading Direction

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Matajinimvar, S.; Choobbasti, A.J.; Kutanaei, S.S. The Effect of Construction Moisture Content on the Mechanical, Shear and Environmental Characteristics of Clay Stabilized with Cement and CS: A Micro and Macro Study. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raftari, M.; Dehghanbanadaki, A.; Rashid, A.S.A.; Kassim, K.A.; Mahjoub, R. Long-Term Compressibility and Shear Strength Properties of Cement-Treated Clay in Deep Cement Mixing Method. Transp. Infrastruct. Geotechnol. 2024, 11, 3381–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Zhang, X.; Cai, S.; Zhou, Z.; An, R.; Zhang, X. Mechanical Characteristics and Damage Constitutive Model of Fiber-Reinforced Cement-Stabilized Soft Clay. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narloch, P.; Woyciechowski, P.; Kotowski, J.; Gawriuczenkow, I.; Wójcik, E. The Effect of Soil Mineral Composition on the Compressive Strength of Cement Stabilized Rammed Earth. Materials 2020, 13, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, T.S.; Miura, N. Soft Clay Behaviour: Analysis and Assessment, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, J.; Mesbah, A.; Oggero, M.; Walker, P. Building houses with local materials: Means to drastically reduce the environmental impact of construction. Build. Environ. 2001, 36, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, P. Earth Building: Methods and Materials, Repair and Conservation; Standards Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Cheng, X.; Huang, S.; Jiang, M. Identifying technology for structural damage based on the impedance analysis of piezoelectric sensor. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 2522–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guettala, A.; Abibsi, A.; Houari, H. Durability study of stabilized earth concrete under both laboratory and climatic conditions exposure. Constr. Build. Mater. 2006, 20, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anysz, H.; Narloch, P. Designing the Composition of Cement Stabilized Rammed Earth Using Artificial Neural Networks. Materials 2019, 12, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NZS 4298:1998; Materials and Workmanship for Earth Buildings. Standards New Zealand, 1998.

- Rui, A.; Daniel, V.; Tiago, F.; Carolina, M.; Nuno, M.; Real, V. Rammed Earth: Feasibility of a Global Concept Applied Locally. In Proceedings of the 13th National Congress of Geotechnics, Lisbon, Portugal, 17–20 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Aalborg Universitet Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciancio, D.; Jaquin, P. An Overview of Some Surrent Recommendations on the Suistability of Soils for Rammed Earth. Int. Work. Rammed Earth Mater. Sustain. Struct. Hakka Tulou Forum 2011, 2011, 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rogala, W.; Anysz, H.; Narloch, P. Designing the Composition of Cement-stabilized Rammed Earth with the Association Analysis Application. Materials 2021, 14, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anysz, H.; Rosicki, Ł.; Narloch, P. Compressive Strengths of Cube vs. Cored Specimens of Cement Stabilized Rammed Earth Compared with ANOVA. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Cao, H. Experimental Study on the Mechanical Properties of Rammed Red Clay Reinforced with Straw Fibers. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dialmy, A.; Rguig, M.; Meliani, M. Optimization of the Granular Mixture of Natural Rammed Earth Using Compressible Packing Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesay, T.; Xie, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xue, J. Bio-Based Stabilization of Natural Soil for Rammed Earth Construction: A Review on Mechanical and Water Durability Performance. Polymers 2025, 17, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbà, M.F.; Tesoro, M.; Falcicchio, C.; Foti, D. Rammed Earth with Straw Fibers and Earth Mortar: Mix Design and Mechanical Characteristics Determination. Fibers 2021, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perić, A.; Kraus, I.; Kaluđer, J.; Kraus, L. Experimental Campaigns on Mechanical Properties and Seismic Performance of Unstabilized Rammed Earth—A Literature Review. Buildings 2021, 11, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losini, A.E.; Grillet, A.C.; Woloszyn, M.; Lavrik, L.; Moletti, C.; Dotelli, G.; Caruso, M. Mechanical and Microstructural Characterization of Rammed Earth Stabilized with Five Biopolymers. Materials 2022, 15, 3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Choi, H.; Rye, H.M.; Yoon, K.B.; Lee, D.E. A Study on the Red Clay Binder Stabilized with a Polymer Aqueous Solution. Polymers 2021, 13, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Choi, H.; Yoon, K.B.; Lee, D.E. Performance Evaluation of Red Clay Binder with Epoxy Emulsion for Autonomous Rammed Earth Construction. Polymers 2020, 12, 2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocak, S.; Grant, A. Enhancing the Mechanical Properties of Polymer-Stabilized Rammed Earth Construction. Constr. Mater. 2023, 3, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Antunes, M.A.; Perlot, C.; Villanueva, P.; Abdallah, R.; Seco, A. Evaluation of the Potential of Natural Mining By-Products as Constituents of Stabilized Rammed Earth Building Materials. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, Q.B. Assessing the Rebound Hammer Test for Rammed Earth Material. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Yuan, K.; Zhang, F.; Guo, L. Study on Mechanical Properties and Constitutive Equation of Earth Materials under Uniaxial Compression. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losini, A.E.; Lavrik, L.; Caruso, M.; Woloszyn, M.; Grillet, A.C.; Dotelli, G.; Gallo Stampino, P. Mechanical Properties of Rammed Earth Stabilized with Local Waste and Recycled Materials. Bio-Based Build. Mater. 2022, 1, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, M.V.; Rezende, M.A.; Carrasco, E.; Alves, R.C.; Barbosa, M.T.; Pires Carvalho, E.; Santos, W. Variability in Compression Strength of Rammed Earth Walls. Concilium 2024, 24, 360–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, F.; Fagone, M.; Gallego, R.; Puertas, E.; Ranocchiai, G. Experimental and Numerical Evaluation of the Compressive and Shear Behavior of Unstabilized Rammed Earth. Mater. Struct. Constr. 2023, 56, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiviya, S.K.; Krishnan, A.G.; Kalathuru, M.; Sharma, A.K.; Kolathayar, S. Strength Behavior of Rammed Earth Stabilized with Metakaolin. Lect. Notes Civ. Eng. 2020, 71, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.; Augarde, C.; Pablo, J. A Review of Chemical Stabilisation and Fibre Reinforcement Techniques Used to Enhance the Mechanical Properties of Rammed Earth. Discov. Civ. Eng. 2025, 2, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Tong, L. Engineering Properties of Unstabilized Rammed Earth with Different Clay Contents. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Mater. Sci. Ed. 2017, 32, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 17892-4:2016; Geotechnical Investigation and Testing—Laboratory Testing of Soil—Part 4: Determination of Particle Size Distribution. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 14688-1:2017; Geotechnical Investigation and Testing—Identification and Classification of Soil—Part 1: Identification and Description. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- RILEM TC 274-TCE. Recommendations for the Testing and Characterisation of Earth-Based Materials; RILEM Publications: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Houben, H.; Guillaud, H. Earth Construction: A Comprehensive Guide; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D1633; Standard Test Methods for Compressive Strength of Molded Soil-Cement Cylinders. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2007.

- Tefa, L.; Bassani, M.; Coppola, B.; Palmero, P. Strength Development and Environmental Assessment of Alkali-Activated Construction and Demolition Waste Fines as Stabilizer for Recycled Road Materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 289, 123017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aygörmez, Y. Evaluation of the Red Mud and Quartz Sand on Reinforced Metazeolite-Based Geopolymer Composites. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 43, 102528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, Q.B.; Morel, J.C.; Hans, S.; Meunier, N. Compression Behaviour of Non-Industrial Materials in Civil Engineering by Three Scale Experiments: The Case of Rammed Earth. Mater. Struct. Constr. 2009, 42, 1101–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciancio, D.; Gibbings, J. Experimental Investigation on the Compressive Strength of Cored and Molded Cement-Stabilized Rammed Earth Samples. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 28, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.; Djerbib, Y. Rammed Earth Sample Production: Context, Recommendations and Consistency. Constr. Build. Mater. 2004, 18, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, C.; Ciancio, D. Effect of Compaction Water Content on the Strength of Cement-Stabilized Rammed Earth Materials. Can. Geotech. J. 2014, 51, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 12390-3:2019; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 3: Compressive Strength of Test Specimens. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An Analysis of Variance Test for Normality (Complete Samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Razali, N.; Bee Wah, Y. Power Comparisons of Shapiro-Wilk, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Lilliefors and Anderson-Darling Tests. J. Stat. Model. Anal. 2011, 2, 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Levene, H. Robust Tests for Equality of Variances. In Contributions to Probability and Statistics: Essays in Honor of Harold Hotellin; Olkin, I., Sudhist, G.G., Hoeffding, W., Madow, W.G., Henry, B.M., Eds.; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1960; pp. 278–292. ISBN 9780804705967. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, D.C. Design and Analysis of Experiments, 10th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; Volume 106, ISBN 978-1-119-11347-8. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, B.L. On the Comparison of Several Mean Values: An Alternative Approach. Biometrika 1951, 38, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruxton, G.D. The Unequal Variance T-Test Is an Underused Alternative to Student’s t-Test and the Mann–Whitney U Test. Behav. Ecol. 2006, 17, 688–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K. Note on Regression and Inheritance in the Case of Two Parents. Proc. R. Soc. London 1895, 58, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; SAGE Publications: Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; ISBN 9781446263914. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserstein, R.L.; Lazar, N.A. The ASA’s Statement on p-Values: Context, Process, and Purpose. Am. Stat. 2016, 70, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Beyond Significance Testing: Statistics Reform in the Behavioral Sciences; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anysz, H.; Brzozowski, Ł.; Kretowicz, W.; Narloch, P. Feature Importance of Stabilised Rammed Earth Components Affecting the Compressive Strength Calculated with Explainable Artificial Intelligence Tools. Materials 2020, 13, 2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Clay Minerals | Quartz (%) | Calcite (%) | Goethite (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (%) | Kaolinite (%) | Beidellite (%) | Illite (%) | |||

| 24.3 | 2.2 | 4.7 | 17.4 | 66.9 | 7 | 1.8 |

| Clay Minerals | Quartz and Others (%) | Calcite (%) | Goethite (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (%) | Kaolinite (%) | Beidellite (%) | Illite (%) | |||

| 8.1 | 0.73 | 1.57 | 5.8 | 83.3 | 8 | 0.6 |

| Sample ID | Earth Type: 1—Soil Powder; 0—Natural Soil | Cement Content (%) | Moisture Content (%) | Curing Time (Days) | Direction of Force: 1—Perpendicular; 0—Parallel | Number of Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-s-C9-W9 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 28 | 1 | 6 |

| 4-w-C9-W9 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 28 | 1 | 3 |

| 4-w-C9-W11 | 0 | 9 | 11 | 28 | 1 | 3 |

| 4-w-C9-W13 | 0 | 9 | 13 | 28 | 1 | 3 |

| 3-w-C12-W9 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 28 | 1 | 3 |

| 3-w-C12-W9 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 28 | 1 | 3 |

| 3a-w-C12-W9 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 28 | 0 | 3 |

| 5a-w-C12-W9 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 7a-w-C7-W9 | 0 | 7 | 9 | 28 | 1 | 5 |

| Drop-ball test results |  |  |  |  |  |

| Cracking behaviour | Ball shatters into many small angular fragments; brittle disintegration indicating mixture too dry. | Ball breaks into several medium fragments with visible sharp cracking planes; moisture still insufficient for cohesion. | Ball fractures into a few large compact fragments; cracking pattern consistent with optimum moisture. | Ball remains mostly cohesive with only 2–3 major cracks; onset of over-wetting with reduced brittleness. | Ball deforms plastically and remains largely intact; cohesive failure without distinct cracking planes, indicating excessive moisture. |

| Moisture content | 7% | 8% | 9% | 10% | 11% |

| Sample ID | Earth Type: 1—Soil Powder; 0—Natural Soil | Cement Content (%) | Moisture Content (%) | Curing Time (days) | Pre-Test Density (kg/m3) | UCS (MPa) | Direction of Force: 1—Perpendicular; 0—Parallel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-s-C9-W9-1 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 28 | 2113.34 | 14.69 | 1 |

| 1-s-C9-W9-2 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 28 | 2134.35 | 15.76 | 1 |

| 1-s-C9-W9-3 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 28 | 2144.56 | 14.21 | 1 |

| 1-s-C9-W9-4 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 28 | 2181.80 | 14.37 | 1 |

| 1-s-C9-W9-5 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 28 | 2198.86 | 14.65 | 1 |

| 1-s-C9-W9-6 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 28 | 2138.96 | 15.07 | 1 |

| 4-w-C9-W9-1 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 28 | 2204.06 | 15.01 | 1 |

| 4-w-C9-W9-2 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 28 | 2217.14 | 15.22 | 1 |

| 4-w-C9-W9-3 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 28 | 2207.71 | 15.54 | 1 |

| 4-w-C9-W11-1 | 0 | 9 | 11 | 28 | 2082.24 | 9.26 | 1 |

| 4-w-C9-W11-2 | 0 | 9 | 11 | 28 | 2023.78 | 9.62 | 1 |

| 4-w-C9-W11-3 | 0 | 9 | 11 | 28 | 2089.17 | 10.35 | 1 |

| 4-w-C9-W13-1 | 0 | 9 | 13 | 28 | 1989.31 | 6.87 | 1 |

| 4-w-C9-W13-2 | 0 | 9 | 13 | 28 | 1999.66 | 6.24 | 1 |

| 4-w-C9-W13-3 | 0 | 9 | 13 | 28 | 1999.06 | 6.65 | 1 |

| 3-w-C12-W9-1 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 28 | 2234.71 | 19.90 | 1 |

| 3-w-C12-W9-2 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 28 | 2271.67 | 21.40 | 1 |

| 3-w-C12-W9-3 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 28 | 2230.75 | 20.30 | 1 |

| 3a-w-C12-W9-1 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 28 | 2208.64 | 28.64 | 0 |

| 3a-w-C12-W9-2 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 28 | 2237.40 | 29.06 | 0 |

| 3a-w-C12-W9-3 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 28 | 2232.27 | 27.86 | 0 |

| 5a-w-C12-W9-1 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 1 | 2309.80 | 3.62 | 1 |

| 5a-w-C12-W9-2 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 1 | 2302.53 | 3.97 | 1 |

| 5a-w-C12-W9-3 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 1 | 2307.77 | 3.84 | 1 |

| 5a-w-C12-W9-4 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 1 | 2310.77 | 3.68 | 1 |

| 7a-w-C7-W9-1 | 0 | 7 | 9 | 28 | 2131.90 | 11.03 | 1 |

| 7a-w-C7-W9-2 | 0 | 7 | 9 | 28 | 2107.52 | 11.37 | 1 |

| 7a-w-C7-W9-3 | 0 | 7 | 9 | 28 | 2209.69 | 11.68 | 1 |

| 7a-w-C7-W9-4 | 0 | 7 | 9 | 28 | 2211.86 | 11.20 | 1 |

| 7a-w-C7-W9-5 | 0 | 7 | 9 | 28 | 2114.03 | 11.46 | 1 |

| Variable | Tested Groups | Shapiro–Wilk | Levene’s Test | ANOVA | Welch’s Test | Pearson Correlation (with UCS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cement content | Samples with equal moisture, curing time, load direction | Passed | Passed p = 0.1136 | Significant p = 0 | N/A | N/A |

| Moisture content | Samples with 9% cement, equal curing time and load direction | Passed | Passed p = 0.55196 | Significant p = 0 | N/A | N/A |

| Curing time | Samples with 12% cement, curing 1vs. 28 days | Passed | Failed p = 0.0000 | Significant p = 0.000016 | Significant p = 0.000085 | N/A |

| Soiltype | Samples with equal moisture and cement content | Passed | Passed p = 0.2947 | Not significant p = 0.2243 | N/A | N/A |

| Density | All samples/Excluding 1-day samples/Excluding parallel loading direction | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.200/0.758/0.853 |

| Loading direction | Samples with 12% cement, 28 days curing | Passed | Passed p = 6067 | Significant p = 0.0002 | N/A | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Narloch, P.; Rosicki, Ł. Identification of Key Factors Governing Compressive Strength in Cement-Stabilized Rammed Earth: A Controlled Assessment of Soil Powdering Prior to Mixing. Materials 2026, 19, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010088

Narloch P, Rosicki Ł. Identification of Key Factors Governing Compressive Strength in Cement-Stabilized Rammed Earth: A Controlled Assessment of Soil Powdering Prior to Mixing. Materials. 2026; 19(1):88. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010088

Chicago/Turabian StyleNarloch, Piotr, and Łukasz Rosicki. 2026. "Identification of Key Factors Governing Compressive Strength in Cement-Stabilized Rammed Earth: A Controlled Assessment of Soil Powdering Prior to Mixing" Materials 19, no. 1: 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010088

APA StyleNarloch, P., & Rosicki, Ł. (2026). Identification of Key Factors Governing Compressive Strength in Cement-Stabilized Rammed Earth: A Controlled Assessment of Soil Powdering Prior to Mixing. Materials, 19(1), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010088