Stabilization and Steam Activation of Petroleum-Based Pitch-Derived Activated Carbons for Siloxane and H2S Gas Removal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Activated Carbon Manufacturing with Pitch

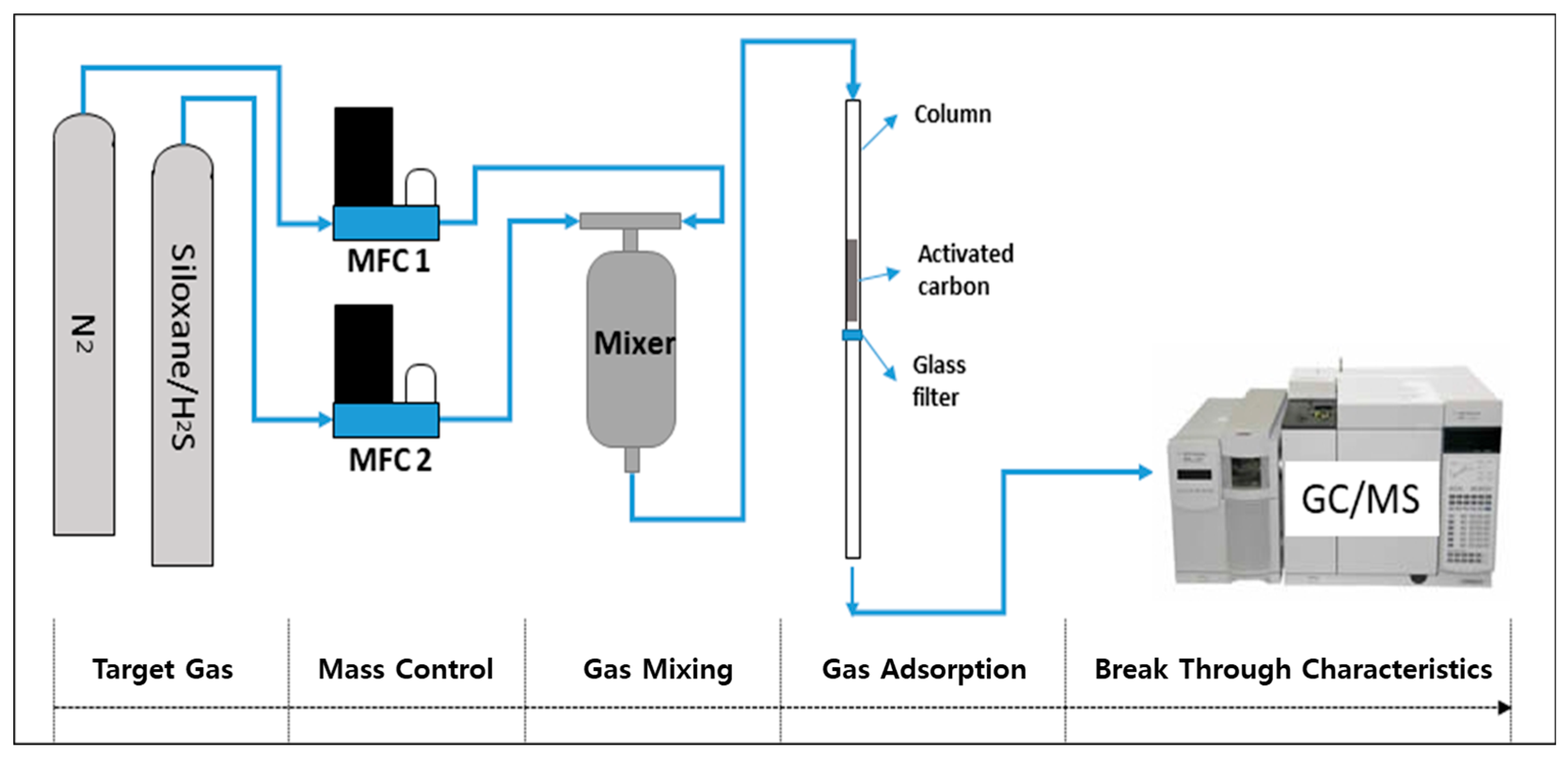

2.3. Siloxane and H2S Gas Adsorption

2.4. Characterization of ACs

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Stabilization Temperature on the Softening and Infusibility Behavior of Pitch

3.2. Oxygen Incorporation Behavior of SP 215 Pitch During Stabilization

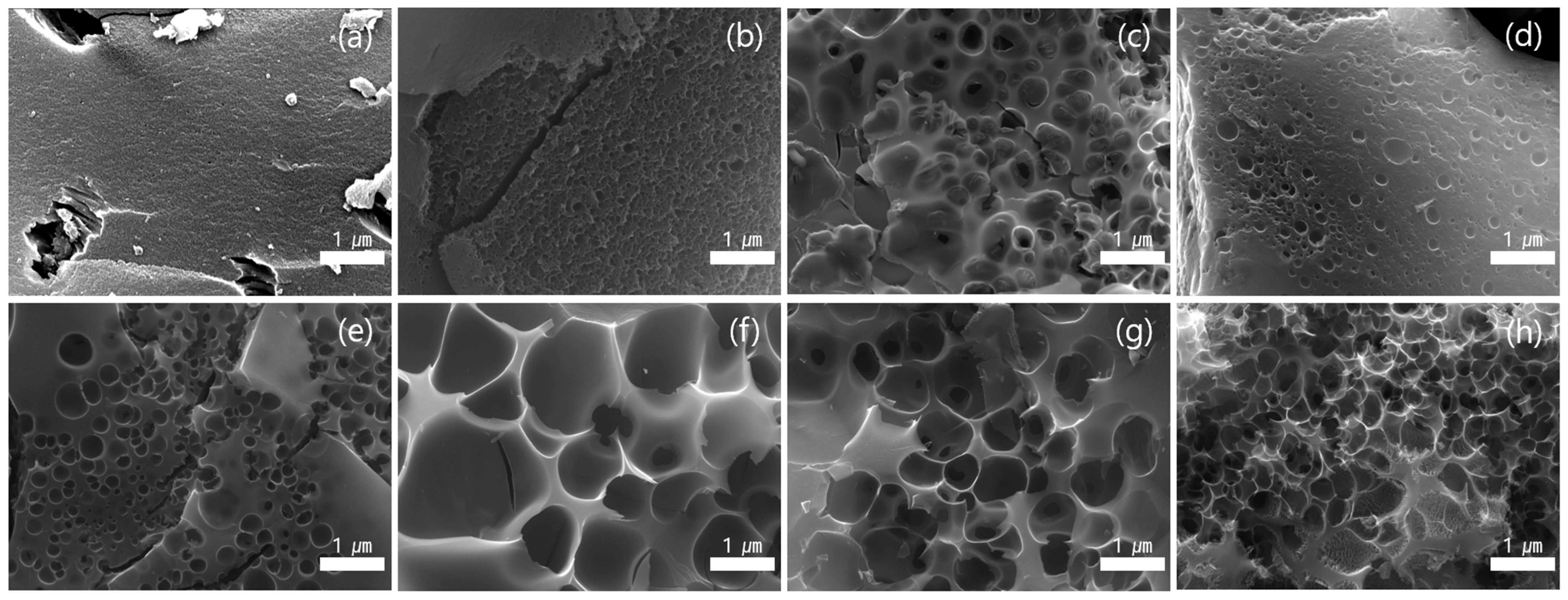

3.3. Morphological Evolution and Pore Formation Behavior of SP 215 Pitch

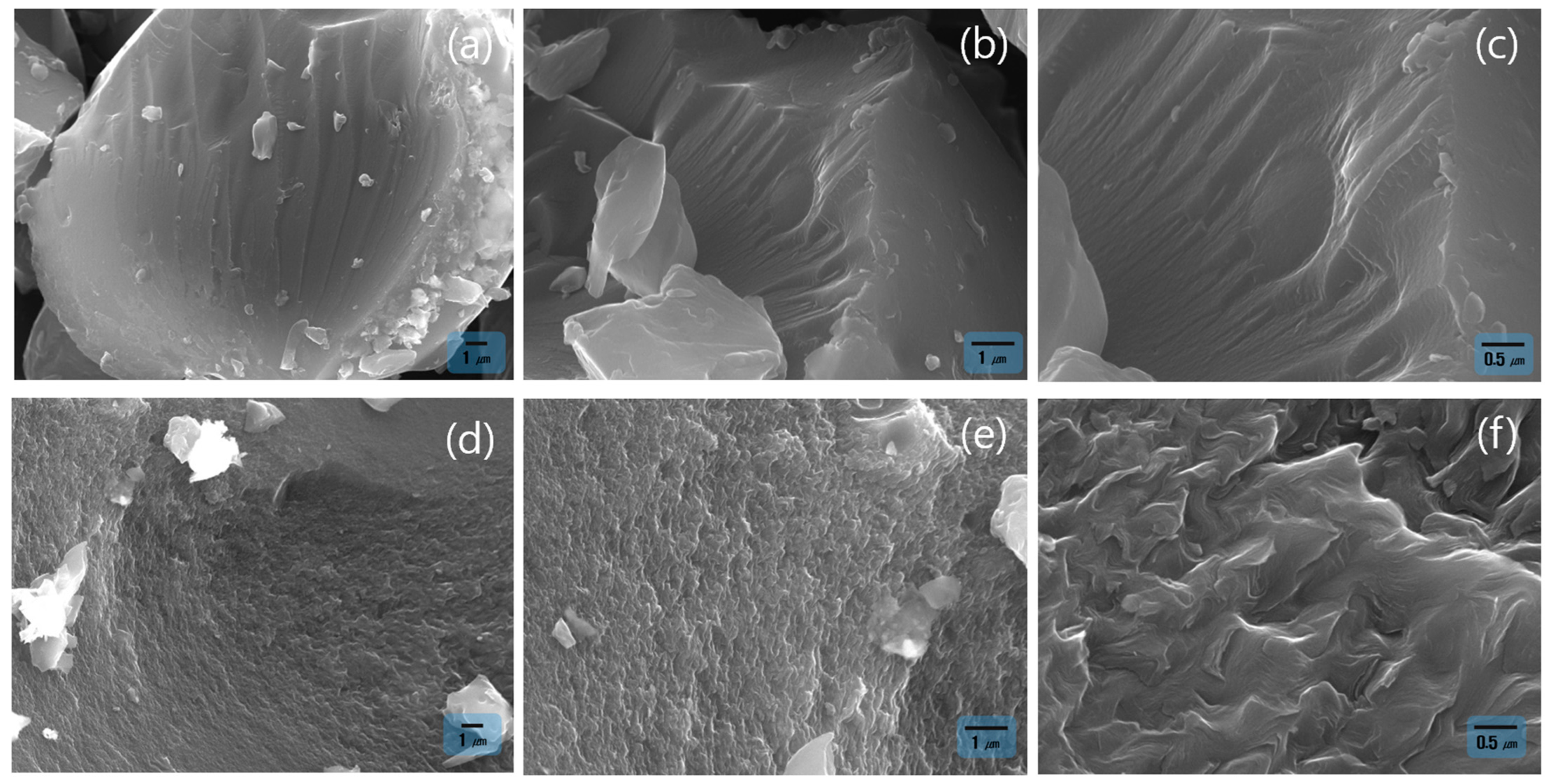

3.4. Surface Morphology of Activated Carbon Under Different Activation Times

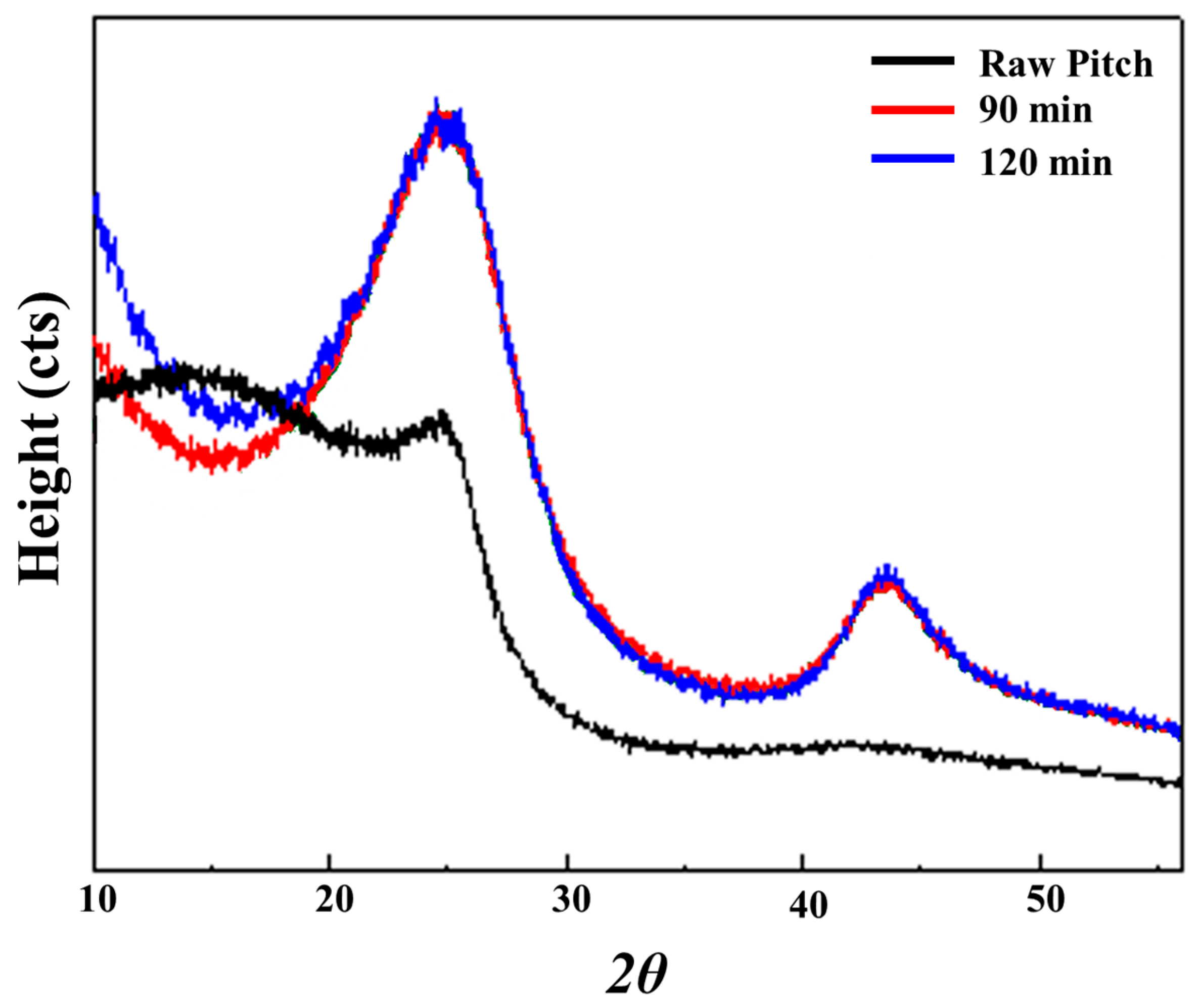

3.5. XRD Analysis of Activated Carbon with Different Activation Times

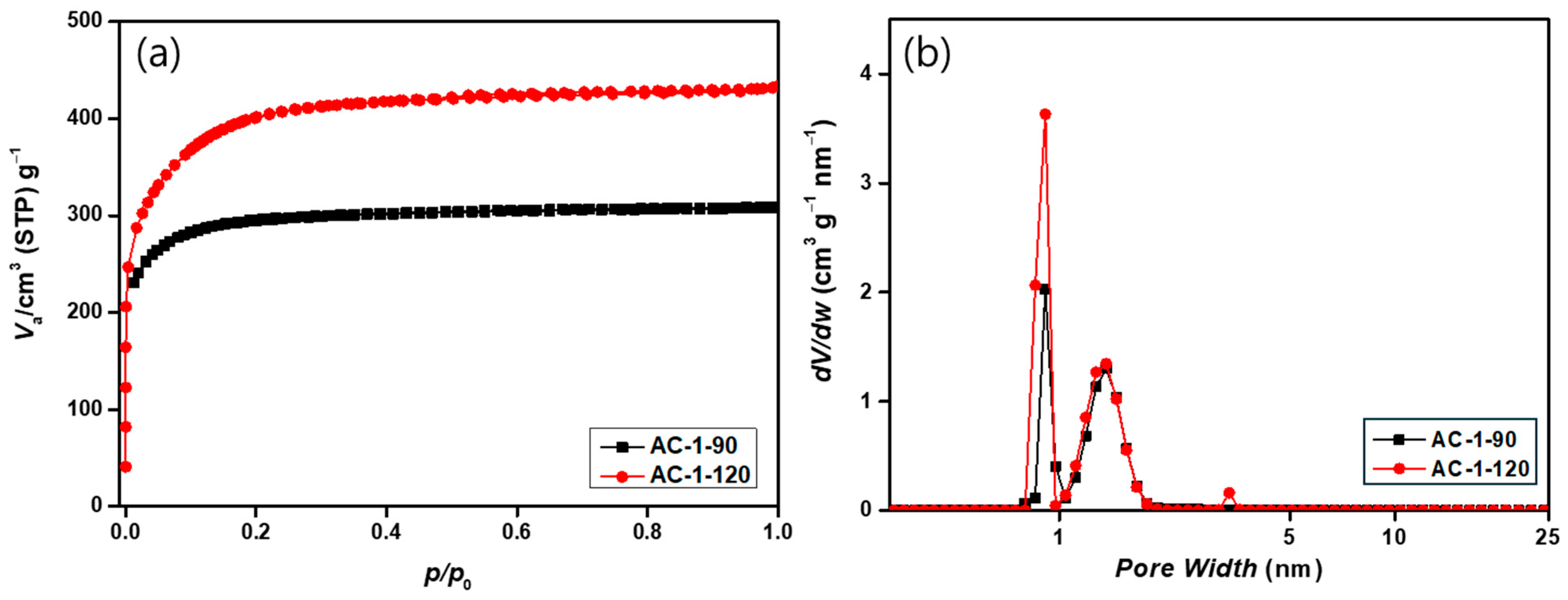

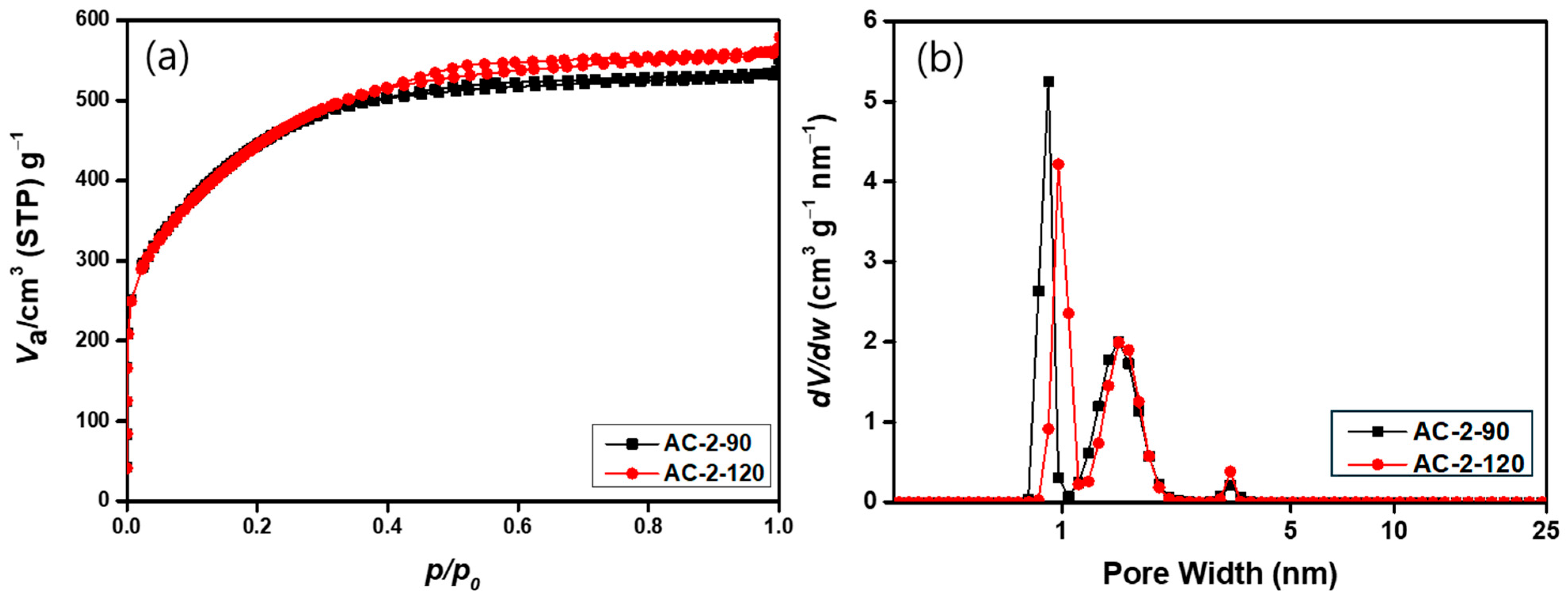

3.6. Textural Properties of Activated Carbon Under Different Activation Conditions

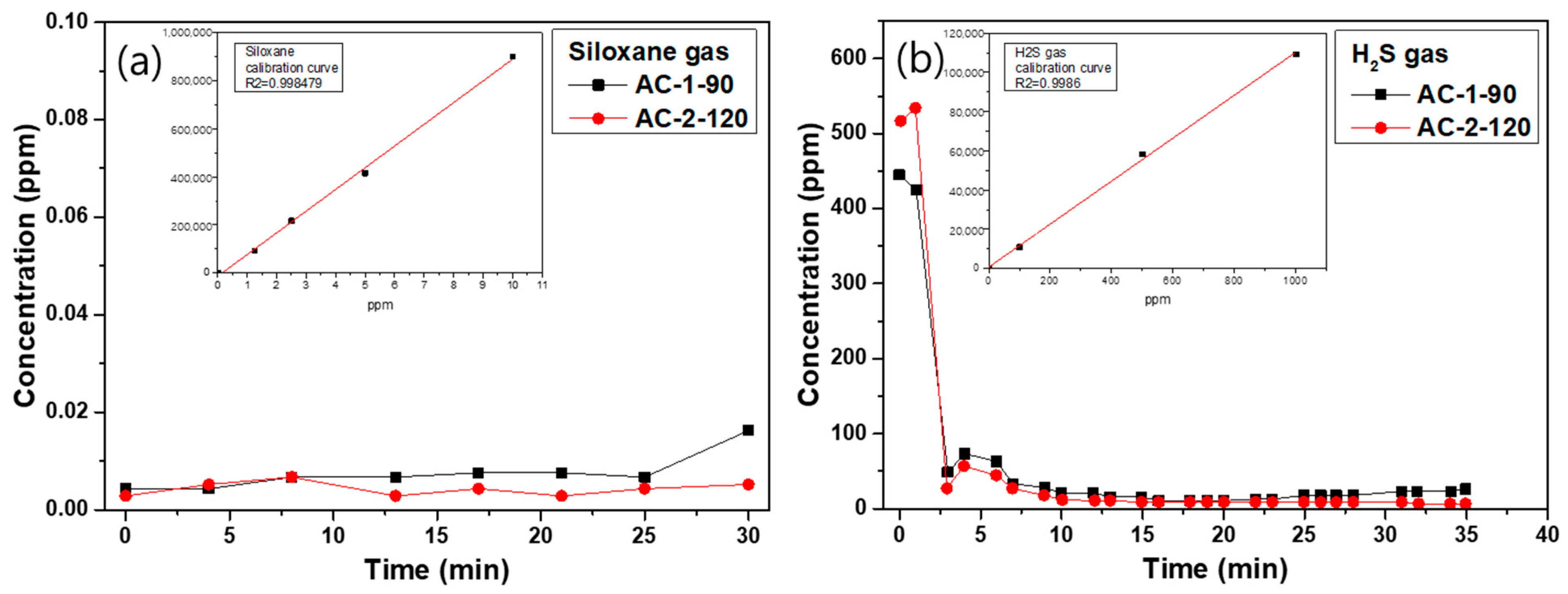

3.7. Adsorption Characteristics of Siloxane and H2S Gases on Activated Carbon

- (1)

- Siloxane gas adsorption behavior

- (2)

- H2S gas adsorption behavior

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moreno-Andrade, I.; Moreno, G.; Quijano, G. Theoretical framework for the estimation of H2S concentration in biogas produced from complex sulfur-rich substrates. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 15959–15966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konkol, I.; Cebula, J.; Świerczek, L.; Piechaczek-Wereszczyńska, M.; Cenian, A. Biogas pollution and mineral deposits formed on the elements of landfill gas engines. Materials 2022, 15, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Pera, A.; Sellaro, M.; Pellegrino, C.; Limonti, C.; Siciliano, A. Combined pre-treatment technologies for cleaning biogas before its upgrading to biomethane: An Italian full-scale anaerobic digester case Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Tan, L.; Xie, L.; Wang, Y.; Ellis, T. Investigation of volatile methyl siloxanes in biogas and the ambient environment in a landfill. J. Environ. Sci. 2020, 91, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inaba, M.; Kuramoto, K.; Soneda, Y. Effect of coexistence of H2S on production of hydrogen and solid carbon by methane decomposition using Fe catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 15077–15091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kim, K.H.; Lim, C.; Lee, Y.S. Carbon-coated SiOx anode materials via PVD and pyrolyzed fuel oil to achieve lithium-ion batteries with high cycling stability. Carbon Lett. 2022, 32, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwood, M. The scientific basis for occupational exposure limits for hydrogen sulphide—A critical commentary. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Q. Advances in adsorption, absorption, and catalytic materials for VOCs generated in typical industries. Energies 2024, 17, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasichnyk, M.; Stanovsky, P.; Polezhaev, P.; Zach, B.; Šyc, M.; Bobák, M.; Jansen, J.C.; Přibyl, M.; Bara, J.E.; Friess, K.; et al. Membrane technology for challenging separations: Removal of CO2, SO2 and NOx from flue and waste gases. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 323, 124436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Segato, T.; Delplancke, M.P.; Terryn, H.; Baron, G.V.; Denayer, J.F.; Cousin-Saint-Remi, J. Hydrogen chloride removal from hydrogen gas by adsorption on hydrated ion-exchanged zeolites. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 381, 122512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Xia, L.; Wang, L.; Xiang, S. Promotional effect of Sr modification on the catalytic oxidation of hydrogen chloride to chlorine over Cu/Y zeolite catalyst. Chem. Phys. 2024, 587, 112410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Bai, L.; Zhao, F.; Bai, L. Activated carbon fibers derived from natural cattail fibers for supercapacitors. Carbon Lett. 2022, 32, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; Kwak, C.H.; Jeong, S.G.; Kim, D.; Lee, Y.S. Enhanced CO2 adsorption of activated carbon with simultaneous surface etching and functionalization by nitrogen plasma treatment. Carbon Lett. 2023, 33, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tan, X.; Li, H.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, G.; Guo, M. Investigation on pore structure regulation of activated carbon derived from sargassum and its application in supercapacitor. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Sun, J.; Ma, C.; Luo, S.; Wu, Z.; Li, W.; Liu, S. Effects of the pore structure of commercial activated carbon on the electrochemical performance of supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 2022, 45, 103457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, O.F., Jr.; Campello-Gómez, I.; Casco, M.E.; Serafin, J.; Silvestre-Albero, J.; Martínez-Escandell, M.; Hotza, D.; Rambo, C.R. Enhanced CO2 capture by cupuassu shell-derived activated carbon with high microporous volume. Carbon Lett. 2023, 33, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaj, K. Adsorptive biogas purification from siloxanes—A critical review. Energies 2020, 13, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundneider, T.; Alonso, V.A.; Abbt-Braun, G.; Wick, A.; Albrecht, D.; Lackner, S. Empty bed contact time: The key for micropollutant removal in activated carbon filters. Water Res. 2021, 191, 116765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altwala, A.; Mokaya, R. Modulating the porosity of activated carbons via pre-mixed precursors for simultaneously enhanced gravimetric and volumetric methane uptake. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 13744–13757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosavi, S.; Lai, C.W.; Gan, S.; Zamiri, G.; Akbarzadeh Pivehzhani, O.; Johan, M.R. Application of efficient magnetic particles and activated carbon for dye removal from wastewater. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 20684–20697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.I.; Seo, S.W.; Kwak, C.H.; Cho, J.H.; Im, J.S. The effect of oxidation on the physical activation of pitch: Crystal structure of carbonized pitch and textural properties of activated carbon after pitch oxidation. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 267, 124591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Wu, Y.C.; Lin, Z.; Taberna, P.L.; Simon, P. Nanoporous carbon for electrochemical capacitive energy storage. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 3005–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.H.; Yang, T.; Song, Y.; Chen, W.S.; Duan, C.F.; Song, H.H.; Tian, X.J.; Gong, Z.Y.; Liu, Z.Y.; Liu, Z.J. A review of the catalytic preparation of mesophase pitch. New Carbon Mater. 2024, 39, 583–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negara, D.N.K.P.; Widiyarta, I.M.; Suriadi, I.G.A.K.; Dwijana, I.G.K.; Penindra, I.M.D.B.; Tenaya, I.G.N.P.; Sukadana, I.G.K.; Ferdinand, A.S. Development of mesoporous activated carbons derived from brewed coffee waste for CO2 adsorption. EUREKA Phys. Eng. 2023, 2, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.T.L.; Gélin, P.; Ferronato, C.; Mascunan, P.; Rac, V.; Chovelon, J.-M.; Postole, G. Siloxane adsorption on activated carbons: Role of the surface chemistry on sorption properties in humid atmosphere and regenerability issues. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 371, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choleva, E.; Mitsopoulos, A.; Dimitropoulou, G.; Romanos, G.E.; Kouvelos, E.; Pilatos, G.; Beltsios, K.; Stefanidis, S.; Lappas, A.; Sfetsas, T. Adsorption of hydrogen sulfide on activated carbon materials derived from the solid fibrous digestate. Materials 2023, 16, 5119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vali, S.A.; Moral-Vico, J.; Font, X.; Sánchez, A. Adsorptive removal of siloxanes from biogas: Recent advances in catalyst reusability and water content effect. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 14, 23259–23273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Li, X.; Xiong, X.; Dong, Z.; Westwood, A.; Li, B.; Ye, C.; Ma, G.; Cui, Z.; Cong, Y.; et al. A comprehensive study on the oxidative stabilization of mesophase pitch-based tape-shaped thick fibers with oxygen. Carbon 2017, 115, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Lee, S.H.; Jung, D.-H. Surface oxidation of petroleum pitch to improve mesopore ratio and specific surface area of activated carbon. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Kim, S.-H.; Kim, B.-J.; Lee, H.-M. Effects of oxygen-containing functional groups on the electrochemical performance of activated carbon for EDLCs. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.; Du, Q.; Yue, C.; Feng, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, A. Hierarchical porosity engineering of biomass-activated carbon cathodes via dual-etching: Directional control of H2O2 electrogeneration and antibiotics degradation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2026, 382, 125953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziejarski, B.; Serafin, J.; Hernández-Barreto, D.F.; Naumovska, E.; Sreńscek-Nazzal, J.; Klomkliang, N.; Tam, E.; Krzyżyńska, R.; Andersson, K.; Knutsson, P. Tailoring highly surface and microporous activated carbons (ACs) from biomass via KOH, K2C2O4 and KOH/K2C2O4 activation for efficient CO2 capture and CO2/N2 selectivity: Characterization, experimental and molecular simulation insights. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 524, 169677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Tan, L.; Zhu, T.; Zhu, H.; Guo, J.; Li, X.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Cong, Y. Engineering optimal pore architecture and defect-rich structure in pitch-derived carbon for efficient sodium-ion storage. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 520, 166230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fu, W.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Sui, Z.; Xu, X. Modulation of pore structure in a microporous carbon for enhanced adsorption of perfluorinated electron specialty gases with efficient separation. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 477, 147128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, K.; Wang, H.; Lin, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, P.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, J.; Cui, H. Advances in micro-/mesopore regulation methods for plant-derived carbon materials. Polymers 2022, 14, 4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Lu, L.; Kottapalli, A.G.P.; Pei, Y. Status and perspectives of hierarchical porous carbon materials in terms of high-performance lithium-sulfur batteries. Carbon Energy 2022, 4, 346–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, M.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Insight into the adsorption behaviors of siloxane on activated carbon fibers. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2025, 387, 113527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yuan, J.; Li, T.; Jiang, X.; Ma, S.; Cen, W.; Jiang, W. A Regenerable N-rich hierarchical porous carbon synthesized from waste biomass for H2S removal at room temperature. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 768, 144452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| NO.1 (°C) | NO.2 (°C) | Average (°C) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 215-180 | 317.7 | 327.6 | 322.7 |

| 215-200 | N.D. | N.D. | - |

| 215-220 | N.D. | N.D. | - |

| 215-240 | N.D. | N.D. | - |

| 215-260 | N.D. | N.D. | - |

| 215-280 | N.D. | N.D. | - |

| 215-300 | N.D. | N.D. | - |

| Weight Before Stabilization (g) | Weight After Stabilization (g) | Difference (g) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 215-180 | 10.000 | 10.261 | 0.261 |

| 215-200 | 9.999 | 10.275 | 0.276 |

| 215-220 | 10.000 | 10.367 | 0.367 |

| 215-240 | 10.002 | 10.427 | 0.425 |

| 215-260 | 10.000 | 10.546 | 0.546 |

| 215-280 | 10.000 | 10.478 | 0.478 |

| 215-300 | 10.000 | 10.610 | 0.610 |

| SP 215 | 215-180 | 215-200 | 215-220 | 215-240 | 215-260 | 215-280 | 215-300 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C (wt.%) | 93.75 | 91.28 | 90.36 | 88.51 | 87.93 | 85.26 | 85.20 | 82.56 |

| H (wt.%) | 5.38 | 4.97 | 4.78 | 4.45 | 4.28 | 3.98 | 3.97 | 3.45 |

| N (wt.%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S (wt.%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| O (wt.%) | 0.87 | 3.75 | 4.86 | 7.04 | 7.79 | 10.76 | 10.83 | 13.99 |

| 90 min | 120 min | |

|---|---|---|

| 2θ | 24.75 | 24.60 |

| Height (cts) | 3128.02 | 2840.29 |

| FWHM | 6.9 | 7.18 |

| d-space (Å) | 3.593 | 3.616 |

| Amount of Steam (cm3/min) | 1 | |

|---|---|---|

| Activation Time (min) | 90 | 120 |

| Sample Name | AC-1-90 | AC-1-120 |

| BET Surface Area (m2/g) | 1145.9 | 1402.1 |

| Total Pore Volume (cm3/g) | 0.4775 | 0.6141 |

| Micropore Volume (cm3/g) | 0.3963 | 0.5036 |

| Mesopore Volume (cm3/g) | 0.0812 | 0.1105 |

| Mesoporosity (%) | 16.6 | 18.9 |

| Average Pore Size (Å) | 8.8 | 9.2 |

| Amount of Steam (cm3/min) | 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Activation Time (min) | 90 | 120 |

| Sample Name | AC-2-90 | AC-2-120 |

| BET Surface Area (m2/g) | 1617.7 | 1620.9 |

| Total Pore Volume (cm3/g) | 0.8216 | 0.8638 |

| Micropore Volume (cm3/g) | 0.6418 | 0.6496 |

| Mesopore Volume (cm3/g) | 0.1798 | 0.2142 |

| Mesoporosity (%) | 21.9 | 24.8 |

| Average Pore Size (Å) | 9.2 | 9.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, G.-H.; Kang, J.K.; Bai, B.C.; Park, Y.-W. Stabilization and Steam Activation of Petroleum-Based Pitch-Derived Activated Carbons for Siloxane and H2S Gas Removal. Materials 2025, 18, 5563. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245563

Lee G-H, Kang JK, Bai BC, Park Y-W. Stabilization and Steam Activation of Petroleum-Based Pitch-Derived Activated Carbons for Siloxane and H2S Gas Removal. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5563. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245563

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Geon-Hee, Jin Kyun Kang, Byong Chol Bai, and Yong-Wan Park. 2025. "Stabilization and Steam Activation of Petroleum-Based Pitch-Derived Activated Carbons for Siloxane and H2S Gas Removal" Materials 18, no. 24: 5563. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245563

APA StyleLee, G.-H., Kang, J. K., Bai, B. C., & Park, Y.-W. (2025). Stabilization and Steam Activation of Petroleum-Based Pitch-Derived Activated Carbons for Siloxane and H2S Gas Removal. Materials, 18(24), 5563. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245563