Rapid Stress Relief of Ti-6Al-4V Titanium Alloy by Electropulsing Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Shot-Peened Ti-6Al-4V Plate

2.2. Residual Stress Measurement

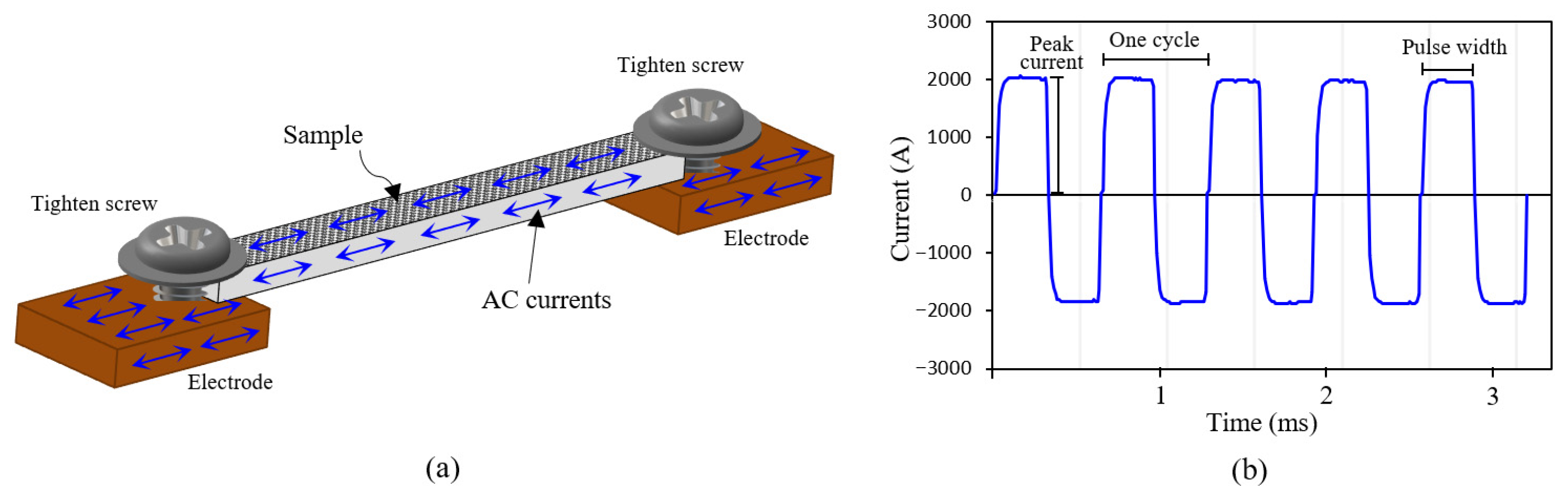

2.3. Electropulsing Treatment (EPT)

2.4. Microstructure Characterization

3. Results

3.1. Residual Stress Results

3.2. Microstructure Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Electropulsing Treatment of Ti-6Al-4V Titanium Alloy

4.2. Understanding Stress Relief Mechanisms of Electropulsing Treatment

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Electropulsing treatment of Ti-6Al-4V alloy for a short period of 114 ms (19 pulse cycles) can relieve approximately 90% of the compressive residual stress without resulting in any observable grain growth or phase transformation. Further optimization of treatment parameters such as current density and pulse width can be further explored to enhance the residual stress relief.

- (2)

- EBSD analysis showed reductions in low-angle grain boundaries (2–10°), local misorientation, and deformed grains in the electropulsed samples.

- (3)

- Stress relief during electropulsing treatment is attributed to a combination of three possible mechanisms: EWF-induced stress, dislocation creep, and dislocation glide by local yielding. The increase of material temperature in electropulsing treatment is an important aspect of the stress relief, as it enables dislocation creep and local yielding to occur.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sala, S.T.; Keller, S.; Chupakhin, S.; Pöltl, D.; Klusemann, B.; Kashaev, N. Effect of laser peen forming process parameters on bending and surface quality of Ti-6Al-4V sheets. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2022, 305, 117578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, N.; Subramaniyan, A.K.; Mondi, P.R. Evaluation methods for residual stress measurement in large components. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 44, 4239–4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhang, M.; Ye, J.L.; Liu, C. Experimental investigation on residual stress distribution in zirconium/titanium/steel tri-metal explosively welded composite plate after cutting and welding of a cover plate. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 64, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshawish, N.; Malinov, S.; Sha, W.; Walls, P. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Ti-6Al-4V manufactured by selective laser melting after stress relieving, hot isostatic pressing treatment and post-heat treatment. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 30, 5290–5296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuelli, L.; Molinari, A.; Facchini, L.; Sbettega, E.; Carmignato, S.; Bandini, M.; Benedetti, M. Effect of heat treatment temperature and turning residual stresses on the plain and notch fatigue strength of Ti-6Al-4V additively manufactured via laser powder bed fusion. Int. J. Fatigue 2022, 162, 107009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalchuk, D.; Melnyk, V.; Melnyk, I.; Savvakin, D.; Dekhtyar, O.; Stasiuk, O.; Markovsky, P. Microstructure and properties of Ti-6Al-4V articles 3D-printed with co-axial electron beam and wire technology. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 30, 5307–5322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Zhao, H.; Wu, B.; Gong, S. Evaluation of residual stresses relaxation by post weld heat treatment using contour method and X-ray diffraction method. Exp. Mech. 2015, 55, 1329–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyankar, V.D.; Chudasama, G. Effect of post weld heat treatment on mechanical properties of pressure vessel steels. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 24675–24684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMS2801C; Heat Treatment of Titanium Alloy Parts. SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2022.

- Pan, L.; Wang, B.; Xu, Z. Effects of electropulsing treatment on residual stresses of high elastic cobalt-base alloy ISO 5832-7. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 792, 994–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.; Sherbondy, J.; Warywoba, D.; Hsu, P.; Roy, S. Room-temperature stress reduction in welded joints through electropulsing. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2022, 299, 117391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.; Zhang, X. Dislocation structure evolution under electroplastic effect. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 761, 138026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudur, S.; Simhambhatla, S.; Reddy, N.V. Residual stress reduction in wire arc additively manufactured parts using in-situ electric pulses. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2023, 28, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, A.; Tan, J.L.; Yang, Y.; Aprilia, A.; Chia, N.; Williams, P.; Jones, M.; Zhou, W. Misorientation and dislocation evolution in rapid residual stress relaxation by electropulsing. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 209, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivaprasad, C.; Subrahmanyam, A.; Reddy, N.V. Effect of electric path in electric pulse aided V-bending of Ti-6Al-4V: An experimental and numerical study. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 100, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subrahmanyam, A.; Saurabh, S.; Praveen, K.; Ramu, G.; Reddy, N.V. Electric pulse aided draw-bending of Ti-6Al-4V. In Proceedings of the Flexible Automation and Intelligent Manufacturing, Detroit, MI, USA, 19–23 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, W.; Zhao, S.; Chen, J. Effect of pulse current on bending behavior of Ti6Al4V alloy. Procedia Eng. 2014, 81, 1799–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, D.; Chu, X.; Yang, Y.; Lin, S.; Gao, J. Effect of electropulsing treatment on microstructure and mechanical behavior of Ti-6Al-4V alloy sheet under argon gas protection. Vacuum 2018, 148, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E2860-20; Standard Test Method for Residual Stress Measurement by X-Ray Diffraction for Bearing Steels. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- Pederson, R. Microstructure and Phase Transformation of Ti-6Al-4V. Ph.D. Dissertation, Luleå University of Technology, Luleå, Sweden, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Neikter, M.; Åkerfeldt, P.; Pederson, R.; Antti, M.L. Microstructure characterization of Ti-6Al-4V from different additive manufacturing processes. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 258, 012007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprecher, A.F.; Mannan, S.L.; Conrad, H. Overview no. 49: On the mechanisms for the electroplastic effect in metals. Acta Metall. 1986, 34, 1145–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Shen, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Xie, C. Non-octahedral-like dislocation glides in aluminum induced by athermal effect of electric pulse. J. Mater. Res. 2016, 31, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, W.B.; Barnett, M.R. Effective values of critical resolved shear stress for slip in polycrystalline magnesium and other hcp metals. Scr. Mater. 2010, 63, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, A.A.; Semiatin, S.L. Anisotropy of the hot plastic deformation of Ti-6Al-4V single-colony samples. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2009, 508, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, R.; Chong, Y.; Li, X.; Abu-Odeh, A.; Rothchild, E.; Chrzan, D.C.; Asta, M.; Morris, J.M.; Minor, A.M. Defect reconfiguration in a Ti-Al alloy via electroplasticity. Nat. Mater. 2021, 20, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milošević, N.; Aleksic, I. Thermophysical properties of solid phase Ti-6Al-4V alloy over a wide temperature range. Int. J. Mater. Res. 2012, 103, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Zhan, M. Mechanism for the macro and micro behaviors of the Ni-based superalloy during electrically-assisted tension: Local joule heating effect. J. Alloy Compd. 2018, 742, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnert, A.A.; Capolungo, L. The kinetics of static recovery by dislocation climb. NPJ Comput. Mater. 2022, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Peak Current (A) | Pulse Width (ms) | Number of Cycles | Thermocouple Measured Peak Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPT1 | 2000 | 3 | 10 | 333 |

| EPT2 | 2000 | 3 | 13 | 475 |

| EPT3 | 2000 | 3 | 19 | 636 |

| EPT4 | 2000 | 3 | 23 | 741 |

| EPT5 | 2000 | 3 | 31 | 877 |

| Sample | Pre-EPT RS (MPa) | Post-EPT RS (MPa) | RS Reduction a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal | Transverse | Longitudinal | Transverse | Longitudinal | Transverse | |

| EPT1 | −521 ± 17 | −591 ± 26 | −401 ± 8 | −421 ± 7 | 23% | 29% |

| EPT2 | −506 ± 26 | −530 ± 17 | −238 ± 39 | −205 ± 15 | 53% | 61% |

| EPT3 | −489 ± 1 | −502 ± 2 | −47 ± 8 | −43 ± 5 | 90% | 91% |

| EPT4 | −513 ± 9 | −523 ± 11 | 6 ± 7 | −16 ± 6 | 99% * | 97% |

| EPT5 | −513 ± 6 | −527 ± 30 | 40 ± 6 | 13 ± 4 | 92% * | 98% * |

| Sample | Observed Microstructure | Average β-Phase Size (µm) |

|---|---|---|

| As-peened | Equiaxed α grains + intergranular β-phases | 0.73 |

| EPT1 | Equiaxed α grains + intergranular β-phases | 0.77 |

| EPT2 | Equiaxed α grains + intergranular β-phases | 0.78 |

| EPT3 | Equiaxed α grains + intergranular β-phases | 0.77 |

| EPT4 | Equiaxed α grains + intergranular β-phases | 0.95 |

| EPT5 | Lamellar α colonies within prior β grains | - |

| Sample | Treatment Duration (ms) | Thermocouple-Measured Peak Temperature (°C) | Simulation-Computed Peak Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EPT1 | 60 | 333 | 451 |

| EPT2 | 78 | 475 | 571 |

| EPT3 | 114 | 636 | 785 |

| EPT4 | 138 | 741 | 969 |

| EPT5 | 186 | 877 | 1270 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aprilia, A.; Tan, J.L.; Ling, Z.; Gill, V.; Williams, P.; Jones, M.A.; Zhou, W. Rapid Stress Relief of Ti-6Al-4V Titanium Alloy by Electropulsing Treatment. Materials 2025, 18, 5555. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245555

Aprilia A, Tan JL, Ling Z, Gill V, Williams P, Jones MA, Zhou W. Rapid Stress Relief of Ti-6Al-4V Titanium Alloy by Electropulsing Treatment. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5555. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245555

Chicago/Turabian StyleAprilia, Aprilia, Jin Lee Tan, Zixuan Ling, Vincent Gill, Paul Williams, Martyn A. Jones, and Wei Zhou. 2025. "Rapid Stress Relief of Ti-6Al-4V Titanium Alloy by Electropulsing Treatment" Materials 18, no. 24: 5555. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245555

APA StyleAprilia, A., Tan, J. L., Ling, Z., Gill, V., Williams, P., Jones, M. A., & Zhou, W. (2025). Rapid Stress Relief of Ti-6Al-4V Titanium Alloy by Electropulsing Treatment. Materials, 18(24), 5555. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245555