Influence of the Si-Layer Thickness on the Structural, Compositional and Resistive Switching Properties of SiO2/Si/SiO2 Stack Layers for Resistive Switching Memories

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

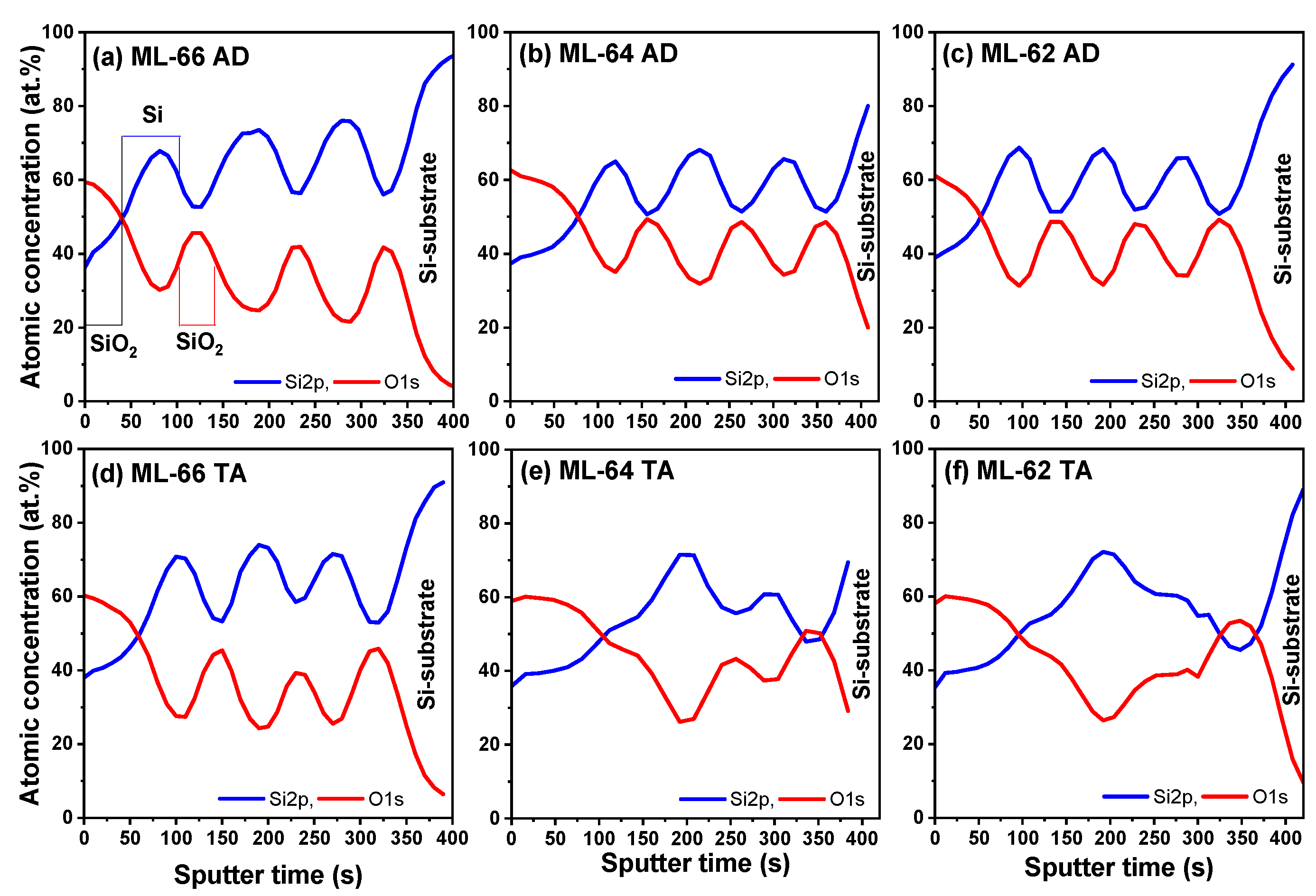

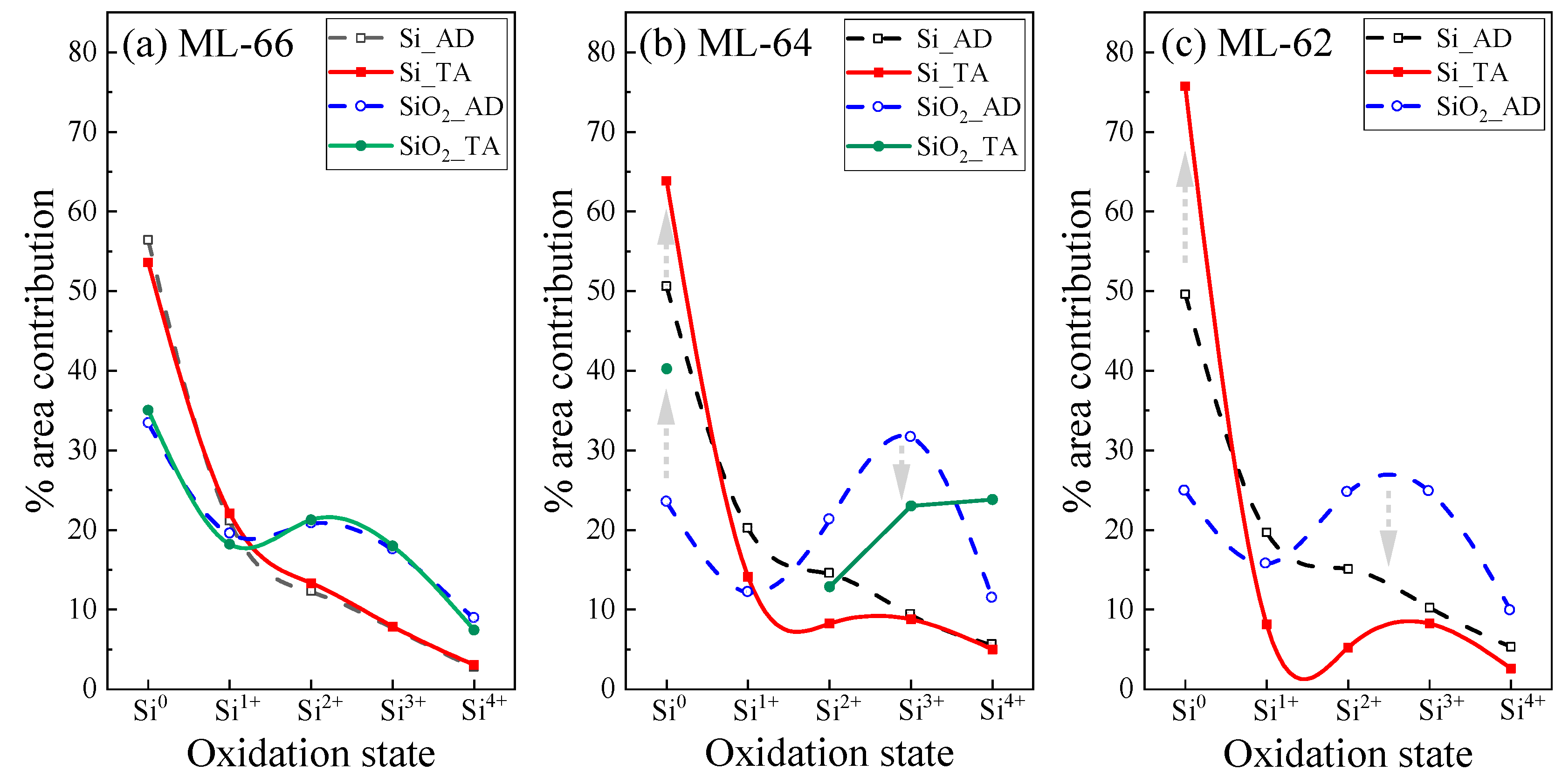

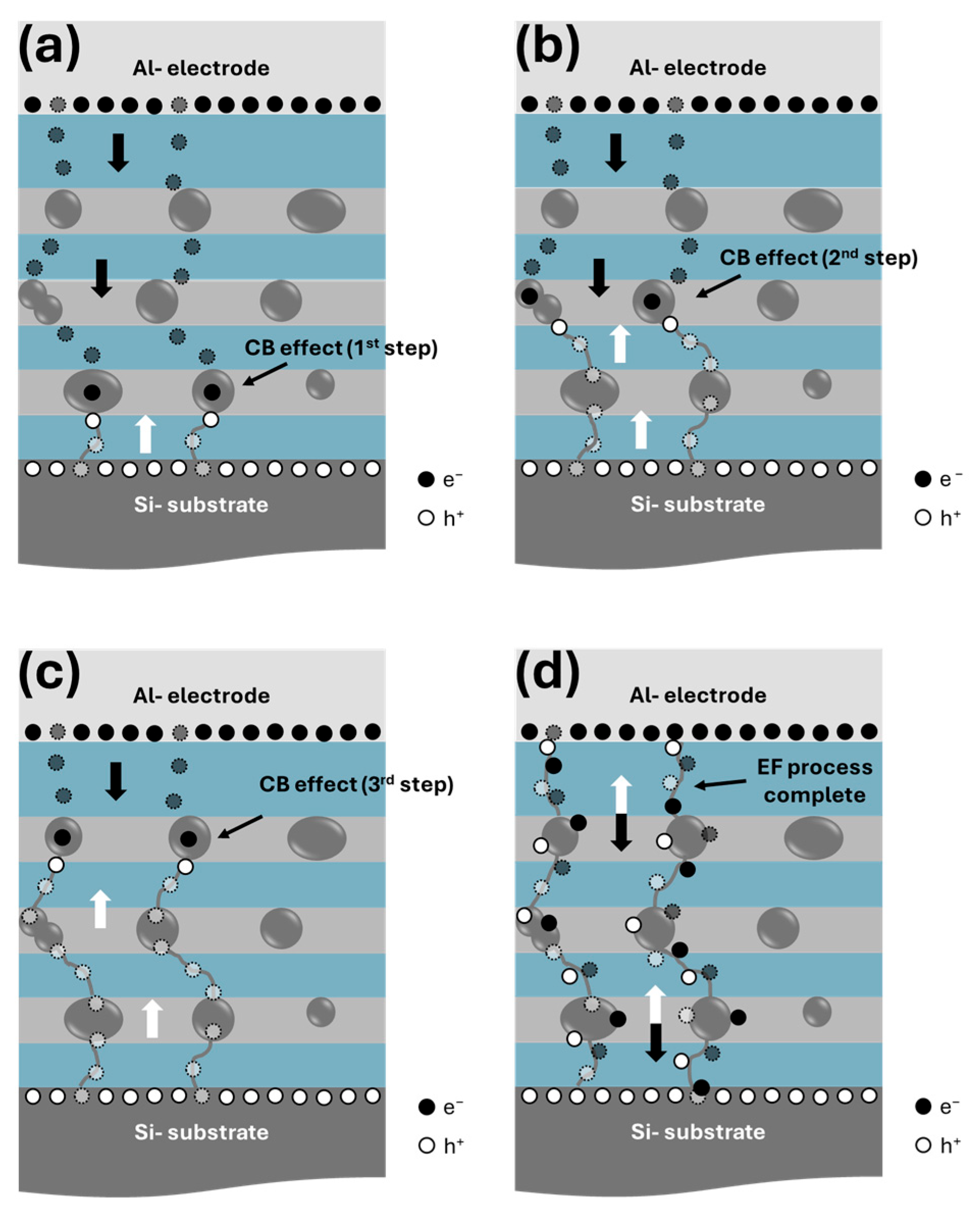

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jeong, H.; Shi, L. Memristor devices for neural networks. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2018, 52, 023003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, C.; Hwang, H.; Yoo, I.K. Perspective: A review on memristive hardware for neuromorphic computation. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 124, 151903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Midya, R.; Xia, Q.; Yang, J.J. Review of memristor devices in neuromorphic computing: Materials sciences and device challenges. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2018, 51, 503002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Yang, J.-Q.; Mao, J.-Y.; Wang, Z.-P.; Wu, S.; Zhou, M.; Chen, T.; Zhou, Y.; Han, S.-T. Recent advances of volatile memristors: Devices, mechanisms, and applications. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2020, 2, 2000055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawa, A. Resistive switching in transition metal oxides. Mater. Today 2008, 11, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Aluguri, R.; Chand, U.; Tseng, T.Y. Metal oxide resistive switching memory: Materials, properties and switching mechanisms. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, S547–S556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Meng, J.; Wang, T. Intelligent flexible memristors for artificial synapses and neuromorphic computing. FlexMat 2025, 2, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Y.; Ren, Y.; Luo, M.; Wang, H.; Zhang, G.; Zhai, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Development of Bio-Voltage Operated Humidity-Sensory Neurons Comprising Self-Assembled Peptide Memristors. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2405145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.S.; Lee, S.; Noh, T.W. Resistive switching phenomena: A review of statistical physics approaches. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2015, 2, 031303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Valle, J.; Ramírez, J.G.; Rozenberg, M.J.; Schuller, I.K. Challenges in materials and devices for resistive-switching-based neuromorphic computing. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 124, 211101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.J.; Pickett, M.D.; Li, X.; Ohlberg, D.A.A.; Stewart, D.R.; Williams, R.S. Memristive switching mechanism for metal/oxide/metal nanodevices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2008, 3, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waser, R.; Aono, M. Nanoionics-based resistive switching memories. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.S.P.; Lee, H.Y.; Yu, S.; Chen, Y.S.; Wu, Y.; Chen, P.S.; Lee, B.; Chen, F.T.; Tsai, M.J. Metal–oxide RRAM. Proc. IEEE 2012, 100, 1951–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ielmini, D. Resistive switching memories based on metal oxides: Mechanisms, reliability and scaling. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2016, 31, 063002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, I.H.; Yasuda, S.; Akinaga, H.; Takagi, H. Nonpolar resistance switching of metal/binary-transition-metal oxides/metal sandwiches: Homogeneous/inhomogeneous transition of current distribution. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77, 035105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatiev, A.; Wu, N.J.; Chen, X.; Liu, S.Q.; Papagianni, C.; Strozier, J. Resistance switching in perovskite thin films. Phys. Status Solidi B 2006, 243, 2089–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Hwang, H. Pr0.7Ca0.3MnO3 (PCMO)-Based Synaptic Devices. In Neuro-Inspired Computing Using Resistive Synaptic Devices; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Szot, K.; Speier, W.; Bihlmayer, G.; Waser, R. Switching the electrical resistance of individual dislocations in single-crystalline SrTiO3. Nat. Mater. 2006, 5, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Tang, Z.; Wang, G.; Fang, Y.; Huang, J.; Zheng, Y. Memristive artificial synapses based on Au-TiO2 composite thin film for neuromorphic computing. APL Mater. 2023, 11, 061103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenbrand, M.; Bakhit, B.; Dou, H.; Xiao, M.; Hill, M.O.; Sun, Z.; Mehonic, A.; Chen, A.; Jia, Q.; Wang, H.; et al. Thin Film Design of Amorphous Hafnium Oxide Nanocomposites Enabling Strong Interfacial Resistive Switching Uniformity. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadg1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Raziq, F.; Ahmad, I.; Ghosh, S.; Kheawhom, S.; Sangaraju, S. Reliable Resistive Switching and Multifunctional Synaptic Behavior in ZnO/NiO Nanocomposite Based Memristors for Neuromorphic Computing. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2025, 7, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliasov, A.; Emelyanov, A.V.; Rylkov, V.; Matsukatova, A.N.; Kukueva, E.V.; Kuchumov, I.D.; Forsh, P.A.; Sitnikov, A.; Demin, V.; Kashkarov, P.K.; et al. Highly reliable resistive switching based on Li intercalation in Cu/(Co–Fe–B)x(SiO2−z)100−x/LiNbO2−y/Cu nanocomposite memristors for neuromorphic computing. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2025, 58, 365305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Dou, H.; Gan, J.B.; Li, C.; Sheng, X.; Lu, J.; Choudhury, A.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Shang, Z.; et al. An Ultra-Robust Memristor Based on Vertically Aligned Nanocomposite with Highly Defective Vertical Channels for Neuromorphic Computing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, e12719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waser, R.; Dittmann, R.; Staikov, G.; Szot, K. Redox-Based Resistive Switching Memories-Nanoionic Mechanisms, Prospects, and Challenges. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 2632–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lu, W. Nanoscale resistive switching devices: Mechanisms and modeling. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 10076–10092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, D.-H.; Kim, K.M.; Jang, J.H.; Jeon, J.M.; Lee, M.H.; Kim, G.H.; Li, X.-S.; Park, G.-S.; Lee, B.; Han, S.; et al. Atomic structure of conducting nanofilaments in TiO2 resistive switching memory. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010, 5, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.-J.; Lee, C.B.; Lee, D.; Lee, S.R.; Chang, M.; Hur, J.H.; Kim, Y.-B.; Kim, C.-J.; Seo, D.H.; Seo, S.; et al. A fast, high-endurance and scalable non-volatile memory device made from asymmetric Ta2O5−x/TaO2−x bilayer structures. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X.; Yu, S.; Wong, H.-S.P. On the switching parameter variation of metal-oxide RRAM—Part I: Physical modeling and simulation methodology. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2012, 59, 1172–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arita, M.; Takahashi, A.; Ohno, Y.; Nakane, A.; Tsurumaki-Fukuchi, A.; Takahashi, Y. Switching operation and degradation of resistive random access memory composed of tungsten oxide and copper investigated using in-situ TEM. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Sánchez, A.; Barreto, J.; Domínguez-Horna, C.; Aceves-Mijares, M.; Luna-López, J. Optical characterization of silicon rich oxide films. Sensors Actuators A Phys. 2008, 142, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshinaga, S.; Ishikawa, Y.; Kawamura, Y.; Nakai, Y.; Uraoka, Y. The optical properties of silicon-rich silicon nitride prepared by plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2019, 90, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; He, L.; Guang, F.; Li, L.; Xin, Z.; Liu, R. A review: Preparation, performance, and applications of silicon oxynitride film. Micromachines 2019, 10, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, O.; Guo, D.; Reynolds, J.; Newbrook, D.; Han, Y.; Beanland, R.; Jiang, L.; de Groot, C.H.K.; Huang, R. An ultra high-endurance memristor using back-end-of-line amorphous SiC. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhong, L.; Natelson, D.; Tour, J.M. Resistive switches and memories from silicon oxide. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 4105–4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehonic, A.; Cueff, S.; Wojdak, M.; Hudziak, S.; Jambois, O.; Labbé, C.; Garrido, B.; Rizk, R.; Kenyon, A.J. Resistive switching in silicon suboxide films. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 111, 074507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehonic, A.; Cueff, S.; Wojdak, M.; Hudziak, S.; Labbé, C.; Rizk, R.; Kenyon, A.J. Electrically tailored resistance switching in silicon oxide. Nanotechnology 2012, 23, 455201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Zhong, L.; Natelson, D.; Tour, J.M. In situ imaging of the conducting filament in a silicon oxide resistive switch. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Jang, S.; Choi, J.-W.; Choi, S.; Jang, S.; Kim, T.-W.; Wang, G. Controllable switching filaments prepared via tunable and well-defined single truncated conical nanopore structures for fast and scalable SiOx memory. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 7462–7470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-T.; Fowler, B.; Wang, Y.; Xue, F.; Zhou, F.; Chang, Y.-F.; Chen, P.-Y.; Lee, J.C. Tristate Operation in Resistive Switching of SiO2 Thin Films. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2012, 33, 1702–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Sánchez, A.; González-Flores, K.E.; Pérez-García, S.A.; González-Torres, S.; Garrido-Fernández, B.; Hernández-Martínez, L.; Moreno-Moreno, M. Digital and Analog Resistive Switching Behavior in Si-ncs Embedded in a Si/SiO2 Multilayer Structure for Neuromorphic Systems. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Flores, K.E.; Palacios-Márquez, B.; Álvarez-Quintana, J.; Pérez-García, S.A.; Licea-Jiménez, L.; Horley, P.; Morales-Sánchez, A. Resistive switching control for conductive Si-nanocrystals embedded in Si/SiO2 multilayers. Nanotechnology 2018, 29, 395203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Flores, K.E.; Horley, P.; Cabañas-Tay, S.A.; Pérez-García, S.A.; Licea-Jiménez, L.; Palacios-Huerta, L.; Aceves-Mijares, M.; Moreno-Moreno, M.; Morales-Sánchez, A. Analysis of the conduction mechanisms responsible for multilevel bipolar resistive switching of SiO2/Si multilayer structures. Superlattices Microstruct. 2020, 137, 106347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zuo, W.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, X.; Wang, W.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, F.; et al. A light-influenced memristor based on Si nanocrystals by ion implantation technique. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 56, 2323–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Vidrier, J.; Frieiro, J.L.; Blázquez, O.; Yazicioglu, D.; Gutsch, S.; González-Flores, K.E.; Zacharias, M.; Hernández, S.; Garrido, B. Photoelectrical reading in ZnO/Si NCs/p-Si resistive switching devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2020, 116, 193503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpens, R.; Lesage, A.; Fujii, M.; Gregorkiewicz, T. Size confinement of Si nanocrystals in multinanolayer structures. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, F.G.; Ley, L. Photoemission study of SiOx (0 ≤ x ≤ 2) alloys. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 8383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipp, H.R. Optical properties of non-crystalline Si, SiO, SiOx and SiO2. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1971, 32, 1935–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, K.; Klinkenberg, E.; Stern, A. Theoretical study of the gradual chemical transition at the Si-SiO2 interface. Phys. Status Solidi B 1986, 135, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavilla, N.R.; Solanki, C.S.; Vasi, J. Raman spectroscopy of silicon-nanocrystals fabricated by inductively coupled plasma chemical vapor deposition. Phys. E 2013, 52, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wirth, A.; Downer, M.C.; Mendoza, B.S. Second-harmonic and linear optical spectroscopic study of silicon nanocrystals embedded in SiO2. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2011, 84, 165316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Xu, S.; Ostrikov, K. Single-step, rapid low-temperature synthesis of Si quantum dots embedded in an amorphous SiC matrix in high-density reactive plasmas. Acta Mater. 2010, 58, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslova, N.E.; Antonovsky, A.A.; Zhigunov, D.M.; Timoshenko, V.Y.; Glebov, V.N.; Seminogov, V.N. Raman studies of silicon nanocrystals embedded in silicon suboxide layers. Semiconductors 2010, 44, 1040–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatryb, G.; Podhorodecki, A.; Hao, X.J.; Misiewicz, J.; Shen, Y.S.; Green, M.A. Correlation between stress and carrier nonradiative recombination for silicon nanocrystals in an oxide matrix. Nanotechnology 2011, 22, 335703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisovyi, I.; Stonio, B.; Jasiński, J.; Wiśniewski, P. Study of RRAM devices with PECVD silicon-oxide resistive switching layer. Solid-State Electron. 2025, 229, 109208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewski, P.; Mazurak, A.; Kądziela, A.; Filipiak, M.; Stonio, B.; Beck, R.B. Silicon-oxide resistive switching memory based on the HSQ layer. Solid-State Electron. 2025, 230, 109223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller, D.; Goetze, S.; Zacharias, M. Rapid thermal annealing of size-controlled Si nanocrystals: Dependence of interface defect density on thermal budget. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 109, 054308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Th (nm) | TO2 (cm−1) | d (nm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | Si | |||

| ML-66 | 6 | 6 | 517.7 | ~6.0 |

| ML-64 | 4 | 518.7 | ~8.5 | |

| ML-62 | 2 | 518.7 | ~8.5 | |

| Device | SET Voltage | HRS SET | LRS SET | LRS/HRS Ratio | RESET Voltage | HRS RESET | LRS RESET | LRS/HRS Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V | A | ON ↑ | V | A | OFF ↓ | |||

| ML-66 | −3.1 ± 0.5 | 1.6 × 10−11 | 2.7 × 10−4 | 1.6 × 107 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 5.2 × 10−12 | 8.2 × 10−5 | 1.6 × 107 |

| ML-64 | 7.1 ± 1.1 | 2.5 × 10−5 | 7.4 × 10−5 | 3.0 | −4.7 ± 0.9 | 1.0 × 10−6 | 6.6 × 10−4 | 6.7 × 102 |

| ML-62 | −3.8 ± 1.2 | 5.5 × 10−9 | 9.7 × 10−5 | 1.8 × 104 | 2.1 ± 1.3 | 1.9 × 10−9 | 4.3 × 10−5 | 2.2 × 104 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morales-Sánchez, A.; González-Flores, K.E.; Germán-Martínez, J.M.; Palacios-Márquez, B.; Ramírez-Rios, J.F.; Flores-Méndez, J.; Benítez-Lara, A.; Ramos-Serrano, J.R.; Hernández-Martínez, L.; Moreno-Moreno, M. Influence of the Si-Layer Thickness on the Structural, Compositional and Resistive Switching Properties of SiO2/Si/SiO2 Stack Layers for Resistive Switching Memories. Materials 2025, 18, 5539. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245539

Morales-Sánchez A, González-Flores KE, Germán-Martínez JM, Palacios-Márquez B, Ramírez-Rios JF, Flores-Méndez J, Benítez-Lara A, Ramos-Serrano JR, Hernández-Martínez L, Moreno-Moreno M. Influence of the Si-Layer Thickness on the Structural, Compositional and Resistive Switching Properties of SiO2/Si/SiO2 Stack Layers for Resistive Switching Memories. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5539. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245539

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorales-Sánchez, Alfredo, Karla E. González-Flores, Jesús M. Germán-Martínez, Braulio Palacios-Márquez, Juan F. Ramírez-Rios, Javier Flores-Méndez, Alfredo Benítez-Lara, Juan R. Ramos-Serrano, Luis Hernández-Martínez, and Mario Moreno-Moreno. 2025. "Influence of the Si-Layer Thickness on the Structural, Compositional and Resistive Switching Properties of SiO2/Si/SiO2 Stack Layers for Resistive Switching Memories" Materials 18, no. 24: 5539. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245539

APA StyleMorales-Sánchez, A., González-Flores, K. E., Germán-Martínez, J. M., Palacios-Márquez, B., Ramírez-Rios, J. F., Flores-Méndez, J., Benítez-Lara, A., Ramos-Serrano, J. R., Hernández-Martínez, L., & Moreno-Moreno, M. (2025). Influence of the Si-Layer Thickness on the Structural, Compositional and Resistive Switching Properties of SiO2/Si/SiO2 Stack Layers for Resistive Switching Memories. Materials, 18(24), 5539. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245539