The Effect of Applied Hydrostatic Pressures in Ferromagnetic Ordered HoM2 [M = (Al, Ni)] Laves Phases: A DFT Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

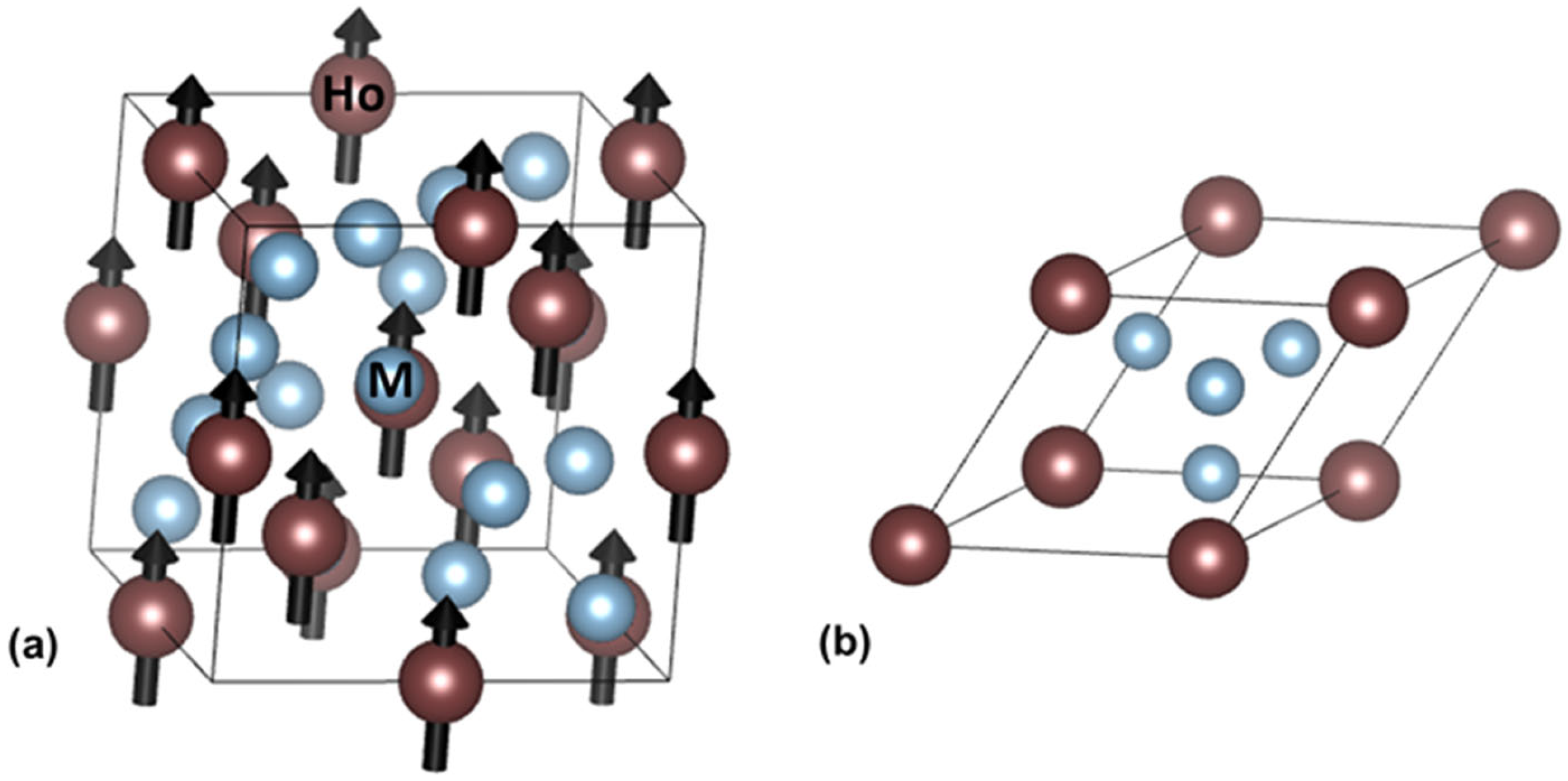

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

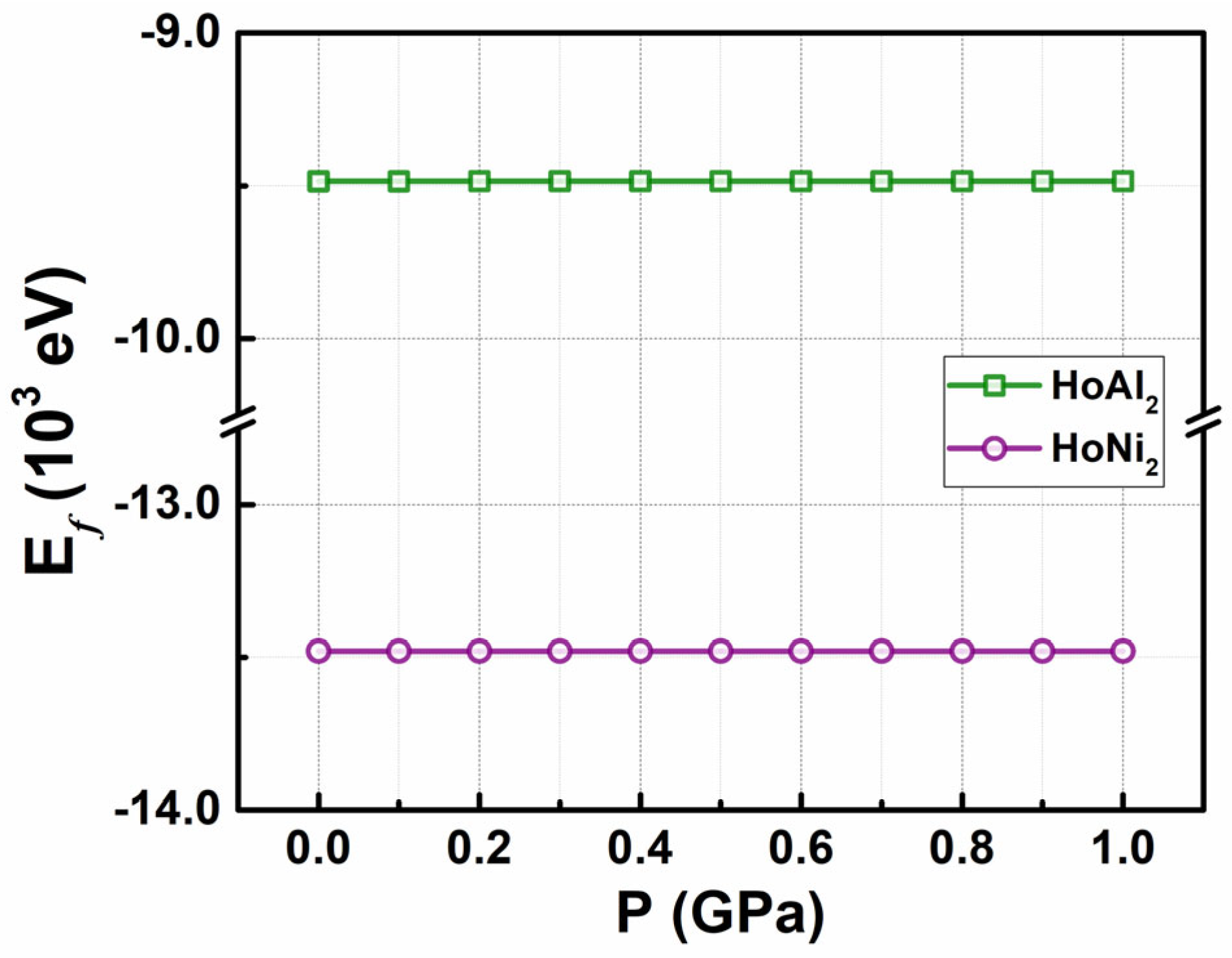

3.1. Electronic Properties

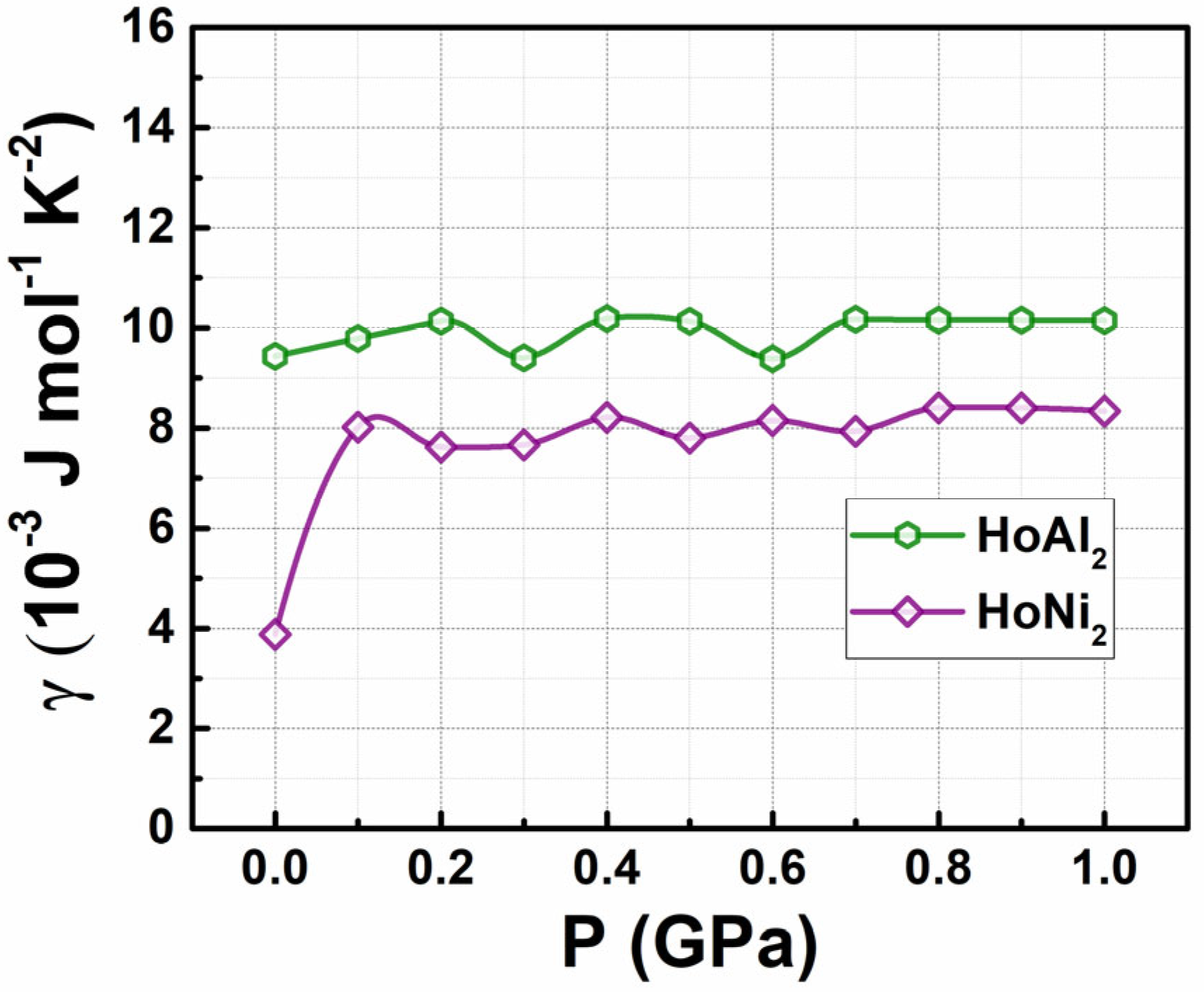

3.2. Determination of Electronic Coefficient in Specific Heat Capacity

| Laves Phases or Elements | N/V (×1028 m−3) | (eV) | (×104 K) | (×10–3 J mol–1 K–2) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HoAl2 | 1.678 | 2.392 | 2.777 | 0.984 | this work |

| HoNi2 | 2.203 | 2.869 | 3.331 | 0.820 | this work |

| K | 1.40 | 2.13 | 2.47 | 1.106 a | [42] |

| Ag | 5.86 | 5.53 | 6.41 | 0.426 a | [42] |

| Cu | 8.47 | 7.06 | 8.19 | 0.333 a | [42] |

| LaAl2 | - | - | - | 10.6 c | [44] |

| LuAl2 | - | - | - | 5.5 c | [44] |

| LaNi2.2 | - | - | - | 4.8 c | [44] |

| LuNi2 | - | - | - | 4.6 c | [44] |

| LuAl2 b | - | - | - | 5.4 c | [45] |

| HoAl2 bulk polycrystalline | - | - | - | 7.0 a | [46] |

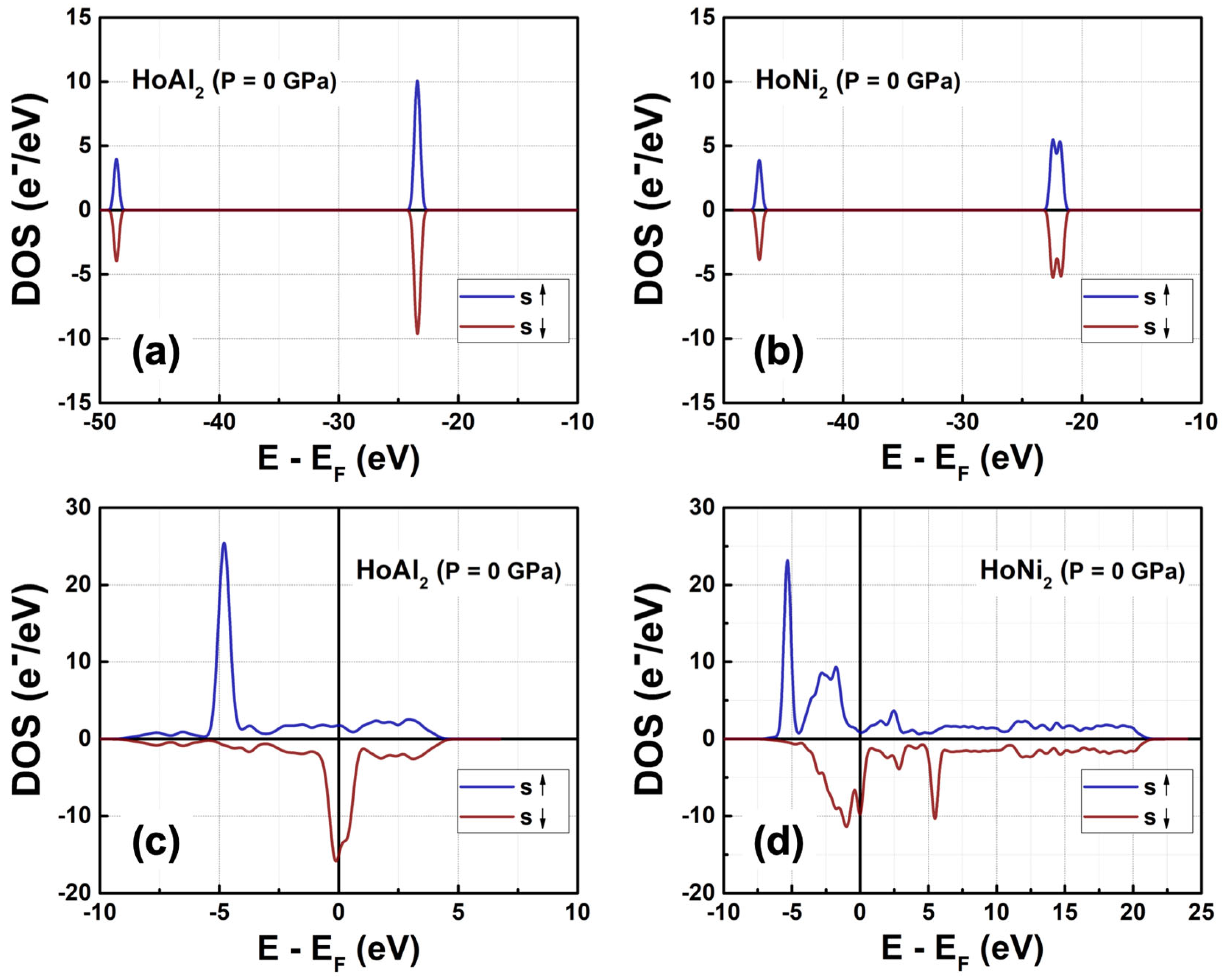

3.3. Electronic Density of States

3.3.1. Total Density of Electronic States at P = 0 GPa

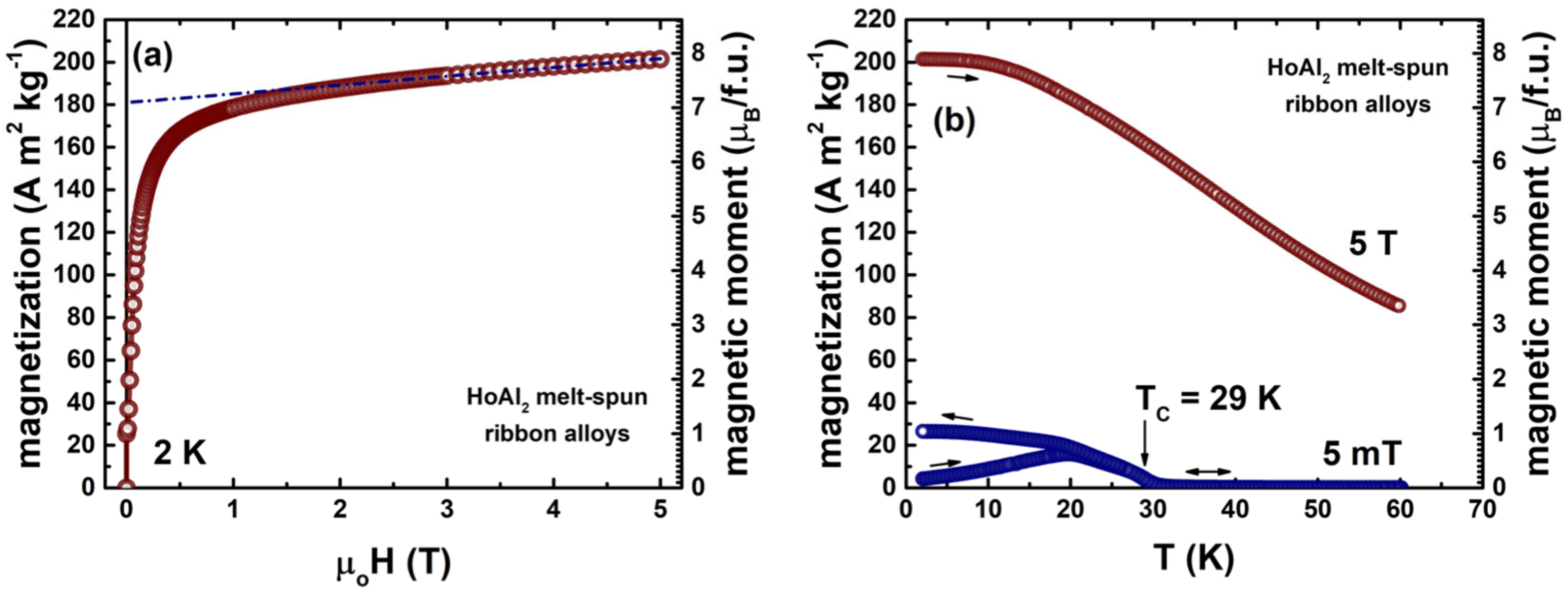

| Laves Phase | Alloy Type | a (Å) | µT (µB/f.u.) | (K) | MS (Am2kg−1) | Magnetization Axis | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HoAl2 | DFT+U framework | 7.810 | 8.61 a | - | 220 a | <001>; intermediate | this work |

| single-crystal | 7.816 c 7.838 | 9.18 b 9.15 c | 31.5 29.0 | 235 b 234 c | <011>; easy | [16] [22] | |

| bulk polycrystalline | 7.8024 | 7.86 | 27.0 | 201 | close to <001>; intermediate | [47] | |

| polycrystalline ribbons (20 m/s) | 7.8109 | 7.08 c, e | 24.0 | 181 c, e | close to <001>; intermediate | [14] | |

| HoNi2 | DFT+U framework | 7.130 | 8.12 a | - | 161 a | <001>; easy | this work |

| single-crystal | - | 8.52 d | 13.4 | 168 d | <001>; easy | [17] | |

| bulk polycrystalline | 7.1318 | 8.40 | 22.0 | 167 | very close to <001>; easy | [47,48] | |

| polycrystalline ribbons (20 m/s) | 7.1497 | 8.02 c | 13.9 | 159 c | close to <001>; easy | [15] |

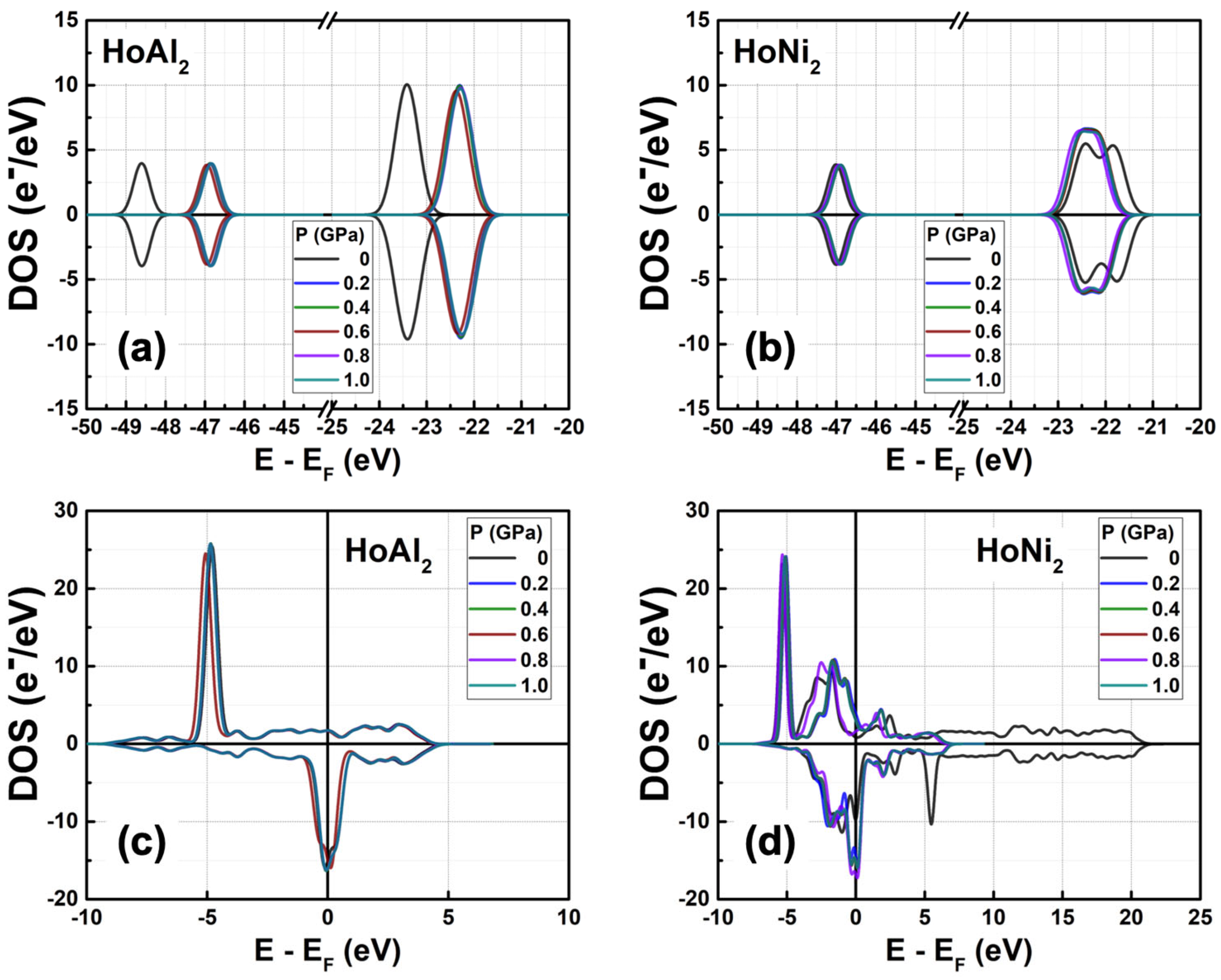

3.3.2. Total Electronic Density of States at 0 GPa < P ≤ 1.0 GPa

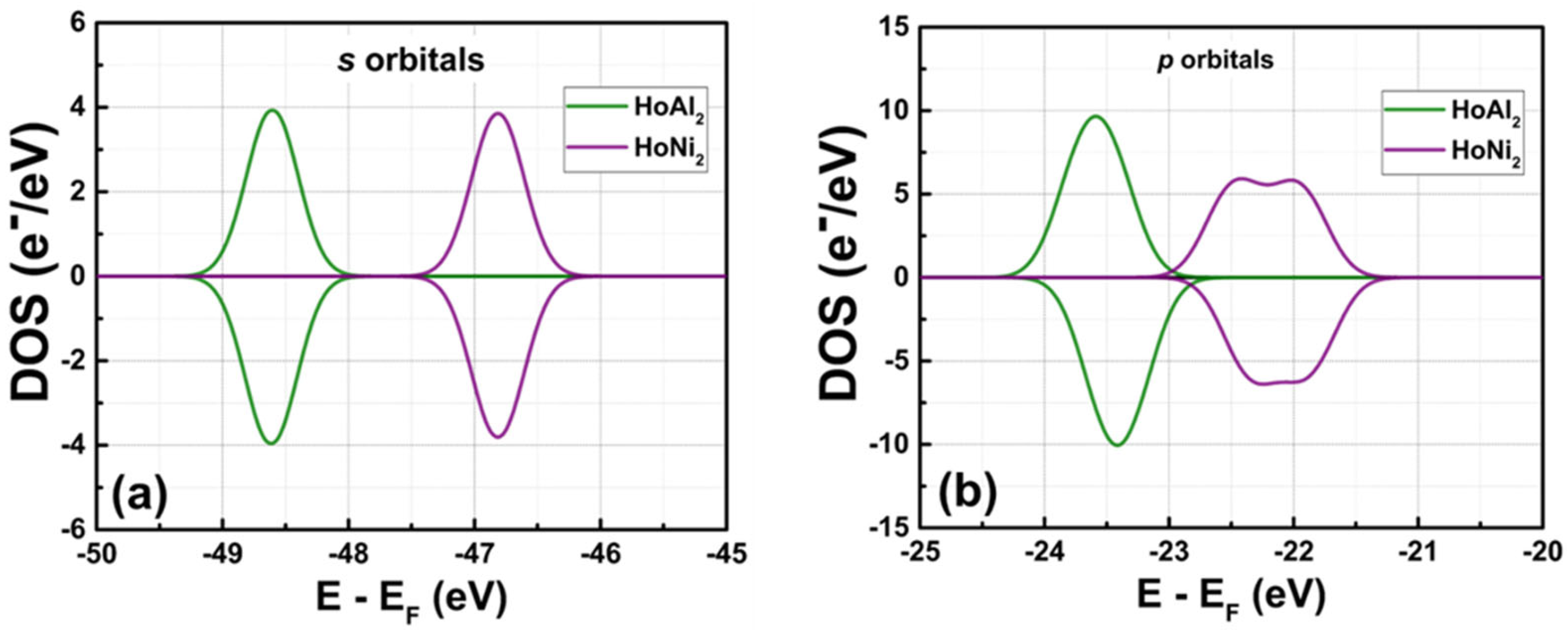

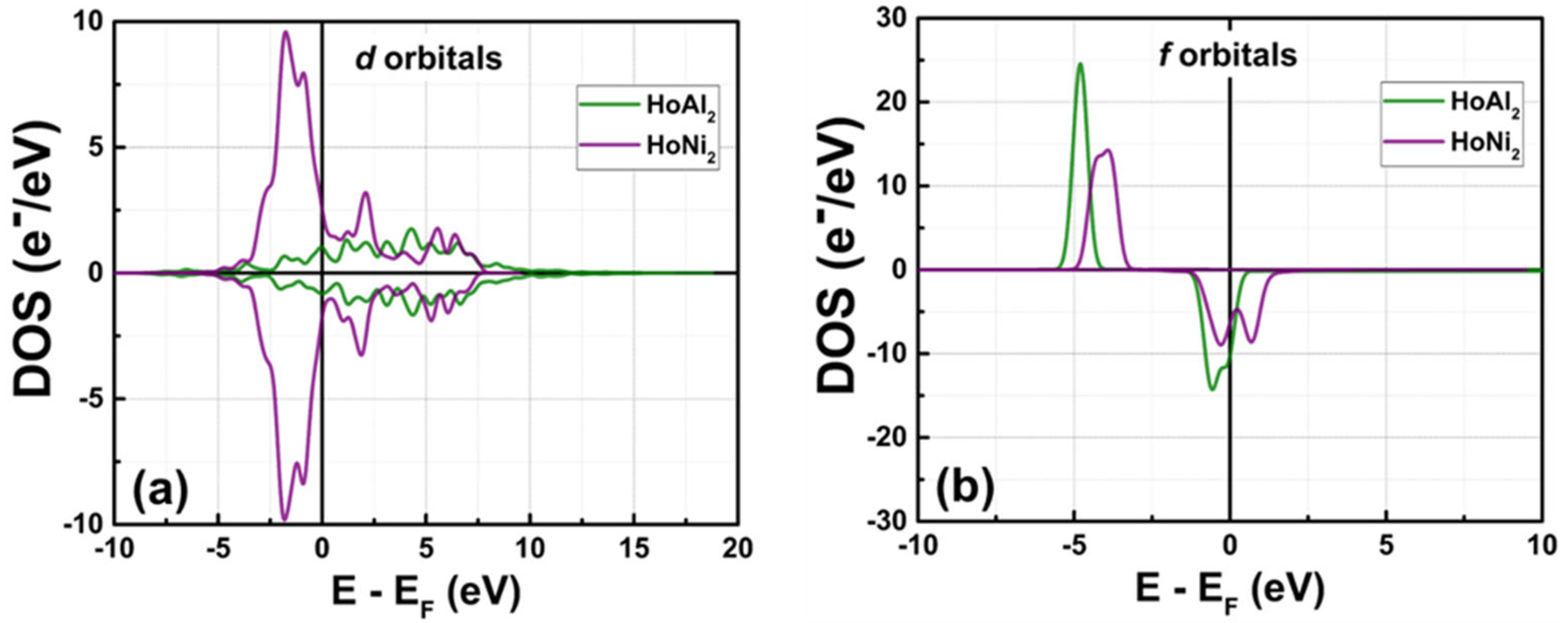

3.3.3. Electronic Partial Density of States at P = 0 GPa

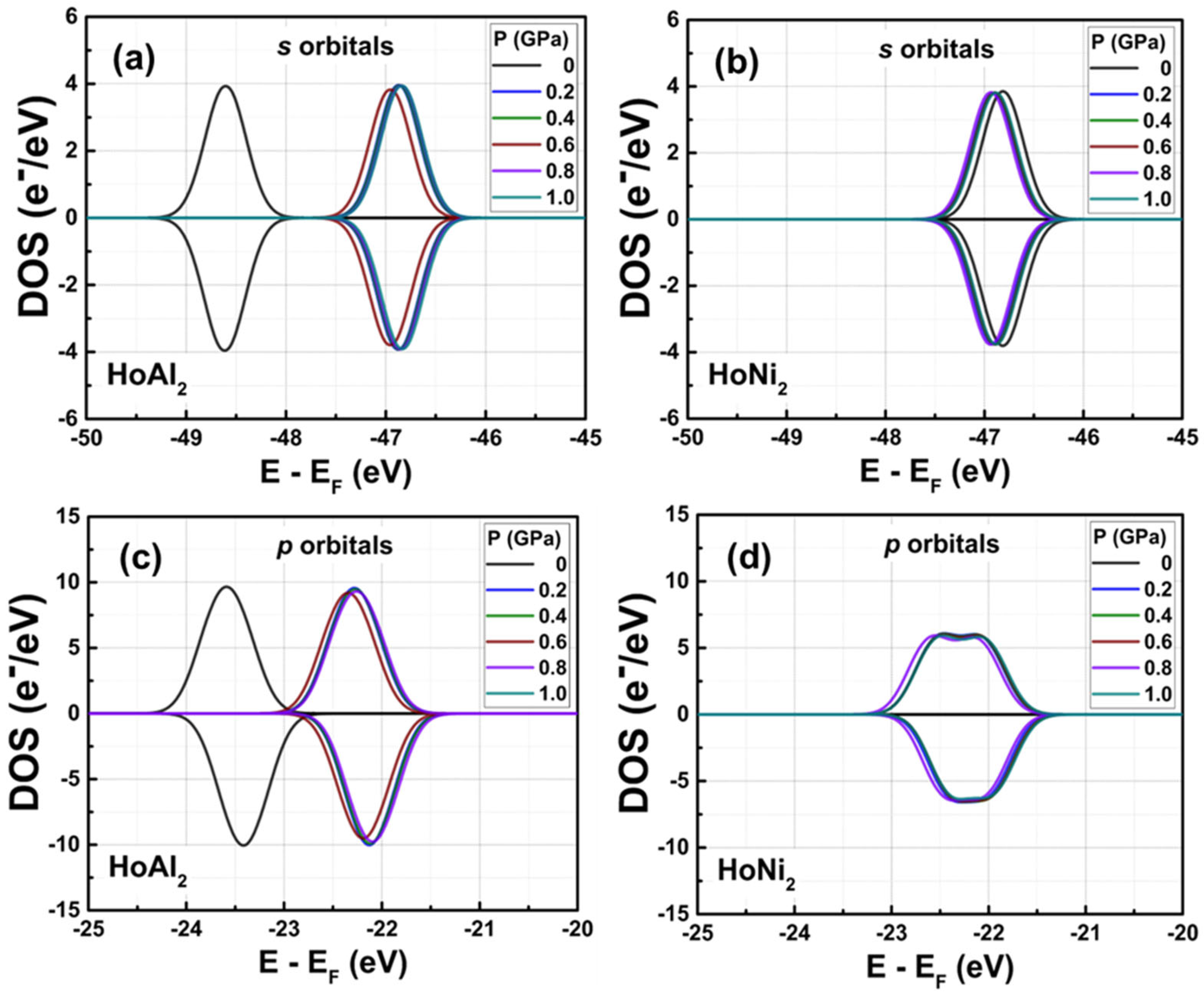

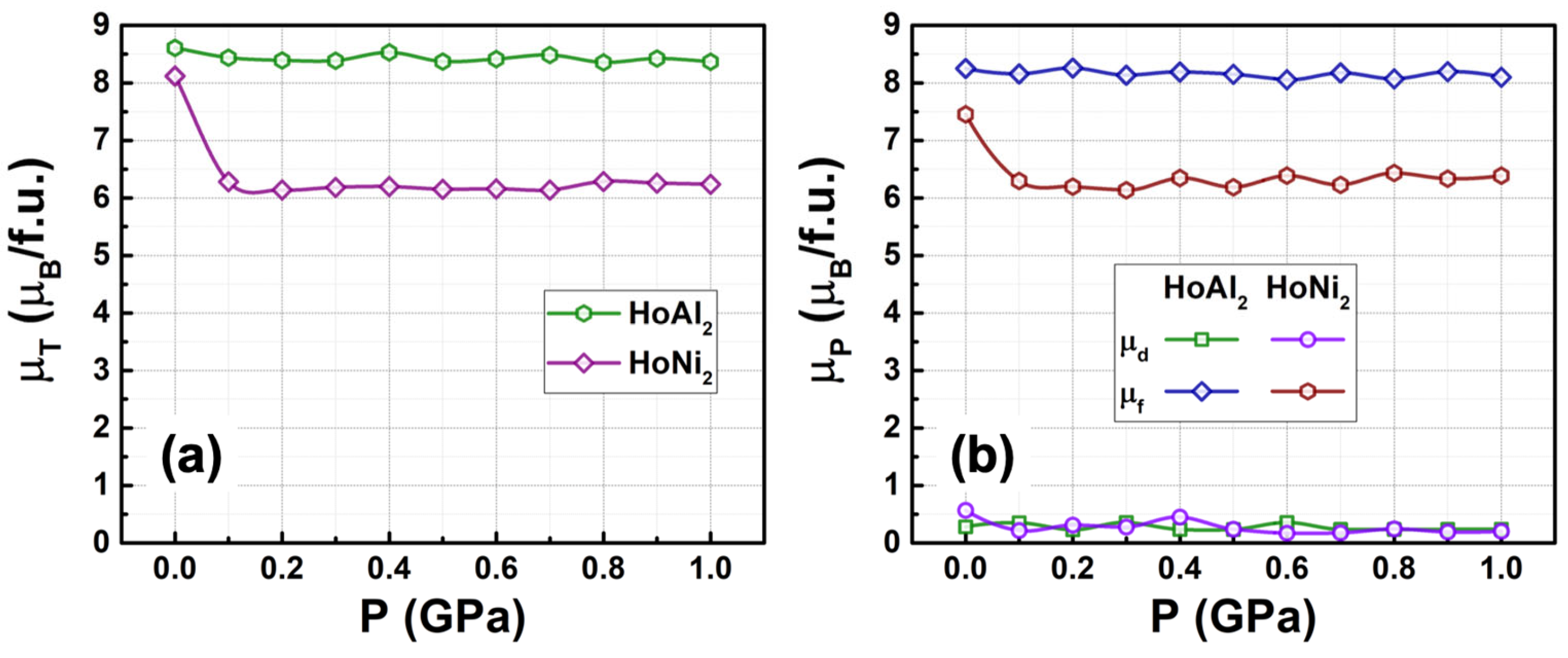

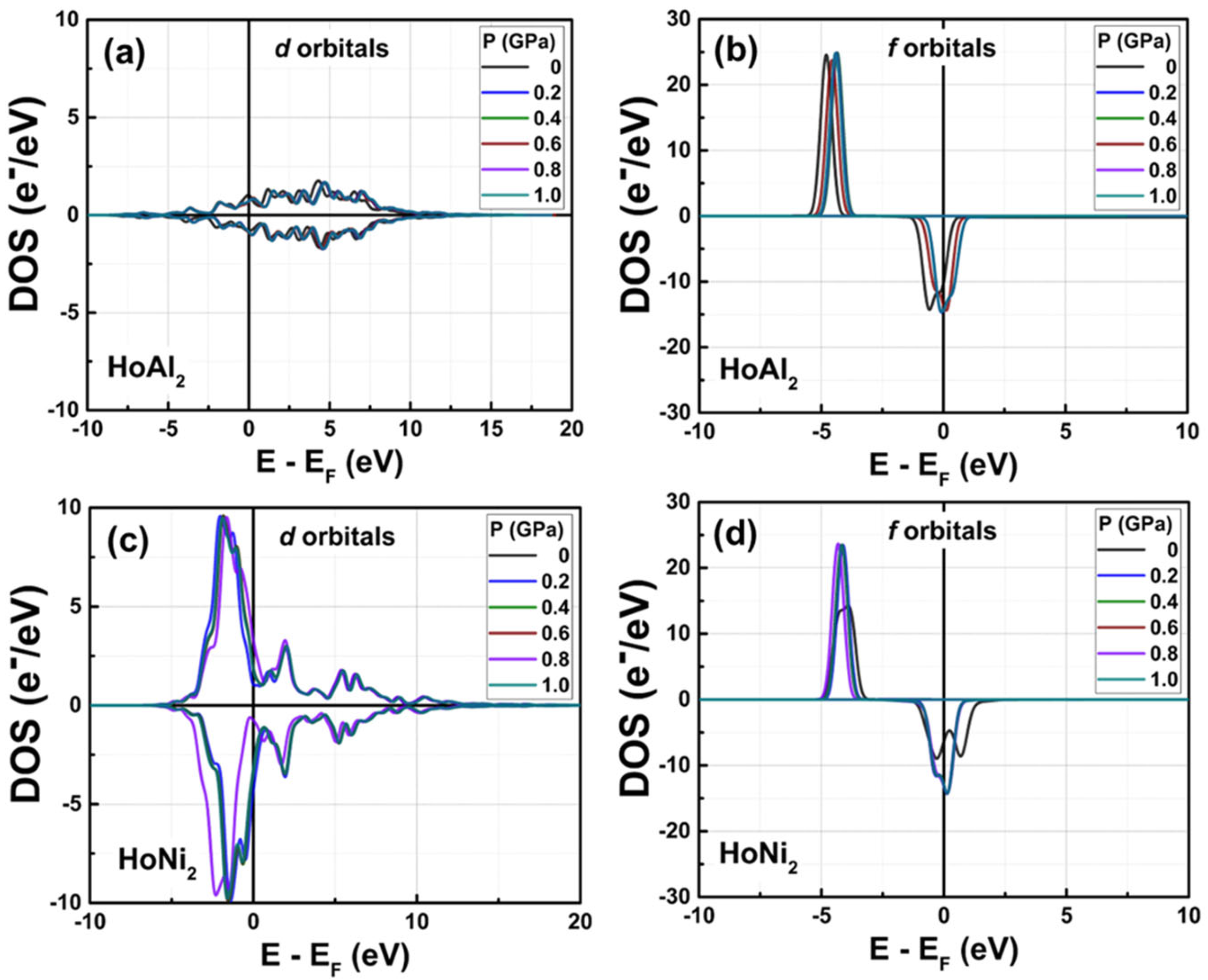

3.3.4. Electronic Partial Density of States at 0 GPa < P ≤ 1.0 GPa

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Pecharsky, V.K.; Gschneider, K.A., Jr. Magnetocaloric effect and magnetic refrigeration. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1999, 200, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, X.; Mathur, N.D. Caloric materials for cooling and heating. Science 2020, 370, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, X.; Kar-Narayan, S.; Mathur, N.D. Caloric materials near ferroic phase transitions. Nat. Mater. 2014, 14, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, V.; Blázquez, J.S.; Ipus, J.J.; Law, J.Y.; Moreno-Ramírez, L.M.; Conde, A. Magnetocaloric effect: From materials research to refrigeration devices. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 93, 112–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Bahl, C.R.H.; Bjørk, R.; Engelbrecht, K.; Nielsen, K.K.; Pryds, N. Materials challenges for high performance magnetocaloric refrigeration devices. Adv. Energy Mater. 2012, 2, 1288–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecharsky, V.K.; Gschneidner, K.A., Jr. Giant magnetocaloric effect in Gd5(Si2Ge2). Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitanovski, A. Energy applications of magnetocaloric materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 1903741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubina, J. Magnetocaloric materials for energy efficient cooling. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 2017, 50, 053002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotani, Y.; Takeya, H.; Lai, J.; Matsushita, Y.; Ohkubo, T.; Miura, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Hono, K. Magnetic refrigeration material operating at a full temperature range required for hydrogen liquefaction. Nat. Comm. 2022, 13, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Batalla, R.U.; Sánchez-Valdés, C.F.; Padrón-Alemán, K.; Sánchez Llamazares, J.L. High-performance spark plasma sintered HoNi2 and ErAl2 Laves phases for hydrogen magnetocaloric liquefaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 172, 151283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Llamazares, J.L.; Ibarra-Gaytán, P.; Sánchez-Valdés, C.F.; Ríos-Jara, D.; Álvarez-Alonso, P. Magnetocaloric effect in ErNi2 melt-spun ribbons. J. Rare Earths 2020, 38, 612–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gschneidner, K.A., Jr.; Pecharsky, V.K. Binary rare earth Laves phases—An overview. Z. Kristallogr. 2006, 221, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, F.; Leineweber, A. Laves phases: A review of their functional and structural applications and an improved fundamental understanding of stability and properties. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 5321–5427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Llamazares, J.L.; Zamora, J.; Sánchez-Valdés, C.F.; Álvarez-Alonso, P. Design and fabrication of a cryogenic magnetocaloric composite by spark plasma sintering based on the RAl2 Laves phases (R = Ho, Er). J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 831, 154779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Llamazares, J.L.; Ibarra Gaytán, P.; Sánchez-Valdés, C.F.; Álvarez-Alonso, P.; Varga, R. Enhanced magnetocaloric effect in rapidly solidified HoNi2 melt spun. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 774, 700–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelp, W.; Leson, A.; Drewes, W.; Purwins, H.G. Magnetization and magnetic excitations in HoAl2. Z. Phys. B—Condens. Matter 1983, 51, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignoux, D.; Givord, F.; Lemaire, R. Magnetic properties of single crystals of GdCo2, HoNi2, and HoCo2. Phys. Rev. B 1975, 12, 3878–3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Bykov, E.; Taskaev, S.; Bogush, M.; Khovaylo, V.; Fortunato, N.; Aubert, A.; Zhang, H.; Gottschall, T.; Wosnitza, J.; et al. A study on rare-earth Laves phases for magnetocaloric liquefaction of hydrogen. Appl. Mat. Today 2022, 29, 101624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gschneidner, K.A., Jr.; Pecharsky, V.K.; Tsokol, A.O. Recent developments in magnetocaloric materials. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2005, 68, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.S.; Hazzledine, P.M. Polytypic transformations in Laves phases. Intermetallics 2004, 12, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Pathak, A.K.; Zarkevich, N.A.; Liu, X.; Mudryk, Y.; Balema, V.; Johnson, D.D.; Pecharsky, V.K. Designed materials with the giant magnetocaloric effect near room temperature. Acta Mater. 2019, 180, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikugawa, N.; Kato, T.; Hayashi, M.; Yamaguchi, H. Single-crystal growth of a cubic Laves-phase ferromagnet HoAl2 by a laser floating-zone method. Crystals 2023, 13, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, M.V.; Plaza, E.J.R.; Campoy, J.C.P. Anisotropic magnetoresistivity and magnetic entropy change in HoAl2. Intermetallics 2016, 715, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, L.A.; Campoy, J.C.P.; Plaza, E.J.R.; de Souza, M.V. Conventional and anisotropic magnetic entropy change in HoAl2 ferromagnetic compound. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2016, 409, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, M.R.; Moze, O.; Algarabel, P.A.; Arnaudas, J.I.; Abell, J.S.; del Moral, A. Magnetoelastic behavior and the spin-reorientation transition in HoAl2. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1988, 21, 2735–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschauer, U.; Braddell, R.; Brechbuhl, S.A.; Derlet, P.M.; Spaldin, N.A. Strain-induced structural instability in FeRh. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 94, 014109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L. First-principles study of Structural phase transition, electronic, elastic and thermodynamic properties of C15-type Laves phases TiCr2 under pressure. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2018, 531, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.D.; Shinde, S.; Gupta, S.D. First principle calculation of structural, electronic and magnetic properties of Mn2RhSi Heusler alloy. AIP Conf. Proc. 2018, 2005, 040004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. First-principles prediction of ferromagnetism in transition-metal doped monolayer AlN. Superlattices Microstruct. 2019, 122, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odkhuu, D.; Tsevelmaa, T.; Sangaa, D.; Tsogbadrakh, N.; Rhim, S.H.; Hong, S.C. First-principles study of magnetization reorientation and perpendicular magnetic anisotropy in CuFe2O4/MgO heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 98, 094408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cococcioni, M.; de Gironcoli, S. Linear response approach to the calculation of the effective interaction parameters in the LDA+U method. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 71, 035105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimov, V.I.; Zaanen, J.; Andersen, O.K. Band theory and Mott insulators: Hubbard U instead of Stoner I. Phys. Rev. B 1991, 44, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moroni, E.G.; Kresse, G.; Hafner, J.; Furthmüller, J. Ultrasoft pseudopotentials applied to magnetic Fe, Co, and Ni: From atoms to solids. Phys. Rev. B 1997, 56, 15629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, J.; Wolverton, C.; Ceder, G. Toward computational materials design: The impact of density functional theory on materials research. MRS Bull. 2006, 31, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staroverov, V.N.; Scuseria, G.E.; Tao, J.; Perdew, J.P. Test of the ladder of density functionals for bulk solids and surfaces. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 69, 075102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelling, D.D.; Harmon, B.N. A technique for relativistic spin-polarised calculations. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1977, 10, 3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewars, E. Computational Chemistry: Introduction to the Theory and Applications of Molecular and Quantum Mechanics, 1st ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2004; ISBN 0-306-48391-2. Print ISBN: 1-4020-7285-6. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, S.J.; Seagall, M.D.; Pickard, C.J.; Hasnip, P.J.; Probert, M.I.J.; Refson, K.; Payne, M.C. First principles methods using CASTEP. Z. Kristallogr. 2005, 220, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, R.F.W. The density in density functional theory. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM 2010, 943, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monkhorst, H.J.; Pack, J.D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 1976, 13, 5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villars, P.; Cenzual, K.; Okamoto, H.; Hulliger, F.; Iwata, S. HoNi2 Crystal Structure: Datasheet from “PAULING FILE MULTINARIES EDITION—2012”; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tipler, P.A.; Llewellyn, R. Modern Physics, 5th ed.; W.H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN-13: 978-0-7167-7550-8; ISBN-10: 0-7167-7550-6. [Google Scholar]

- Cyrot, M.; Lavagna, M. Density of states and magnetic properties of the rare-earth compounds RFe2, RCo2 and RNi2. J. de Phys. 1979, 40, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Ranke, P.J.; Pecharsky, V.K.; Gschneidner, K.A., Jr. Influence of the crystalline electrical field on the magnetocaloric effect of DyAl2, ErAl2 and DyNi2. Phys. Rev. B 1998, 58, 12110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, I.G.; Garcia, D.C.; von Ranke, P.J. Spin reorientation and magnetocaloric effect study in HoAl2 by a microscopic model Hamiltonian. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 102, 073907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campoy, J.C.P.; Plaza, E.J.R.; Coelho, A.A.; Gama, S. Magnetoresistivity as a probe to the field-induced change of magnetic entropy in RAl2 compounds (R = Pr, Nd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er). Phys. Rev. B 2006, 74, 134410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.N.R. Intermetallic rare-earth compounds. Adv. Phys. 1971, 20, 551–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, J.; Wallace, W.E. Magnetic properties of intermetallic compounds between the lanthanides and nickel or cobalt. Inorg. Chem. 1966, 5, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Alloy | HoAl2 | HoNi2 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P (GPa) | B (GPa) | σij (GPa) | a (Å) | dAl-Al (Å) | dHo-Al (Å) | VP (Å3) | Δ (%) | B (GPa) | σij (GPa) | a (Å) | dNi-Ni (Å) | dHo-Ni (Å) | VP (Å3) | Δ (%) |

| 0.0 | 40.66 | −0.00005 | 5.652 | 2.826 | 3.314 | 127.675 | 0.000 | 49.79 | −0.00115 | 5.262 | 2.631 | 3.086 | 103.066 | 0.000 |

| 0.1 | 45.68 | −0.10067 | 5.646 | 2.823 | 3.311 | 127.299 | −0.294 | 56.58 | −0.10030 | 5.258 | 2.629 | 3.083 | 102.840 | −0.219 |

| 0.2 | 52.56 | −0.19968 | 5.640 | 2.820 | 3.307 | 126.908 | −0.600 | 58.98 | −0.19724 | 5.255 | 2.628 | 3.081 | 102.655 | −0.399 |

| 0.3 | 56.69 | −0.29771 | 5.635 | 2.818 | 3.304 | 126.533 | −0.894 | 60.33 | −0.30162 | 5.252 | 2.626 | 3.080 | 102.480 | −0.569 |

| 0.4 | 58.00 | −0.39932 | 5.629 | 2.815 | 3.301 | 126.165 | −1.182 | 68.79 | −0.40011 | 5.248 | 2.624 | 3.077 | 102.241 | −0.801 |

| 0.5 | 60.58 | −0.49793 | 5.623 | 2.812 | 3.297 | 125.780 | −1.484 | 71.50 | −0.50638 | 5.245 | 2.623 | 3.076 | 102.072 | −0.964 |

| 0.6 | 64.07 | −0.60178 | 5.618 | 2.809 | 3.294 | 125.380 | −1.797 | 76.23 | −0.60287 | 5.242 | 2.621 | 3.074 | 101.868 | −1.162 |

| 0.7 | 65.22 | −0.70149 | 5.613 | 2.807 | 3.291 | 125.055 | −2.052 | 82.56 | −0.69933 | 5.239 | 2.620 | 3.072 | 101.703 | −1.322 |

| 0.8 | 66.65 | −0.80276 | 5.607 | 2.804 | 3.288 | 124.681 | −2.345 | 84.36 | −0.80034 | 5.235 | 2.618 | 3.070 | 101.479 | −1.540 |

| 0.9 | 68.37 | −0.89994 | 5.602 | 2.801 | 3.285 | 124.328 | −2.621 | 91.47 | −0.89917 | 5.232 | 2.616 | 3.068 | 101.321 | −1.693 |

| 1.0 | 70.89 | −0.99911 | 5.597 | 2.799 | 3.282 | 123.992 | −2.884 | 98.45 | −0.99998 | 5.229 | 2.615 | 3.066 | 101.132 | −1.876 |

| Physical Magnitude | Alloy | |

|---|---|---|

| HoAl2 | HoNi2 | |

| nS↑ (EF) (e−/eV) | 1.76 | 14.59 |

| nS↓ (EF) (e−/eV) | −15.10 | −9.11 |

| Δn (EF) (e−/eV) | −13.34 | 5.48 |

| (µB/f.u.) | 31.30 | 37.08 |

| (µB/f.u.) | −22.69 | −28.96 |

| (µB/f.u.) | 8.61 | 8.12 |

| (µB/f.u.) | 9.18 † | 8.52 ‡ |

| μs (μB/f.u.) | −0.03 | 0.11 |

| μp (μB/f.u.) | 0.04 | −0.17 |

| μd (μB/f.u.) | 0.28 | 0.57 |

| μf (μB/f.u.) | 8.79 | 7.45 |

| μP (μB/f.u.) | 9.08 | 7.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López-Solenzal, T.; Ríos-Jara, D.; Ramos, M.; Sánchez-Valdés, C.F. The Effect of Applied Hydrostatic Pressures in Ferromagnetic Ordered HoM2 [M = (Al, Ni)] Laves Phases: A DFT Study. Materials 2025, 18, 5510. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245510

López-Solenzal T, Ríos-Jara D, Ramos M, Sánchez-Valdés CF. The Effect of Applied Hydrostatic Pressures in Ferromagnetic Ordered HoM2 [M = (Al, Ni)] Laves Phases: A DFT Study. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5510. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245510

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-Solenzal, Tomás, David Ríos-Jara, Manuel Ramos, and César Fidel Sánchez-Valdés. 2025. "The Effect of Applied Hydrostatic Pressures in Ferromagnetic Ordered HoM2 [M = (Al, Ni)] Laves Phases: A DFT Study" Materials 18, no. 24: 5510. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245510

APA StyleLópez-Solenzal, T., Ríos-Jara, D., Ramos, M., & Sánchez-Valdés, C. F. (2025). The Effect of Applied Hydrostatic Pressures in Ferromagnetic Ordered HoM2 [M = (Al, Ni)] Laves Phases: A DFT Study. Materials, 18(24), 5510. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245510