Research on Creep Behaviors of GH3230 Superalloy Sheets with Side Notches

Highlights

- A series of creep tests on GH3230 superalloy smooth and notch specimens were conducted.

- The creep strain curves and creep life were predicted by the θ parameter method

- Notches exhibited a creep life enhancing effect on GH3230 superalloy under the same net stress level.

- The notched specimens exhibited a significantly accelerated tertiary creep stage.

- The creep strain curves and creep life predicted by the θ parameter method were in good agreement with the test results.

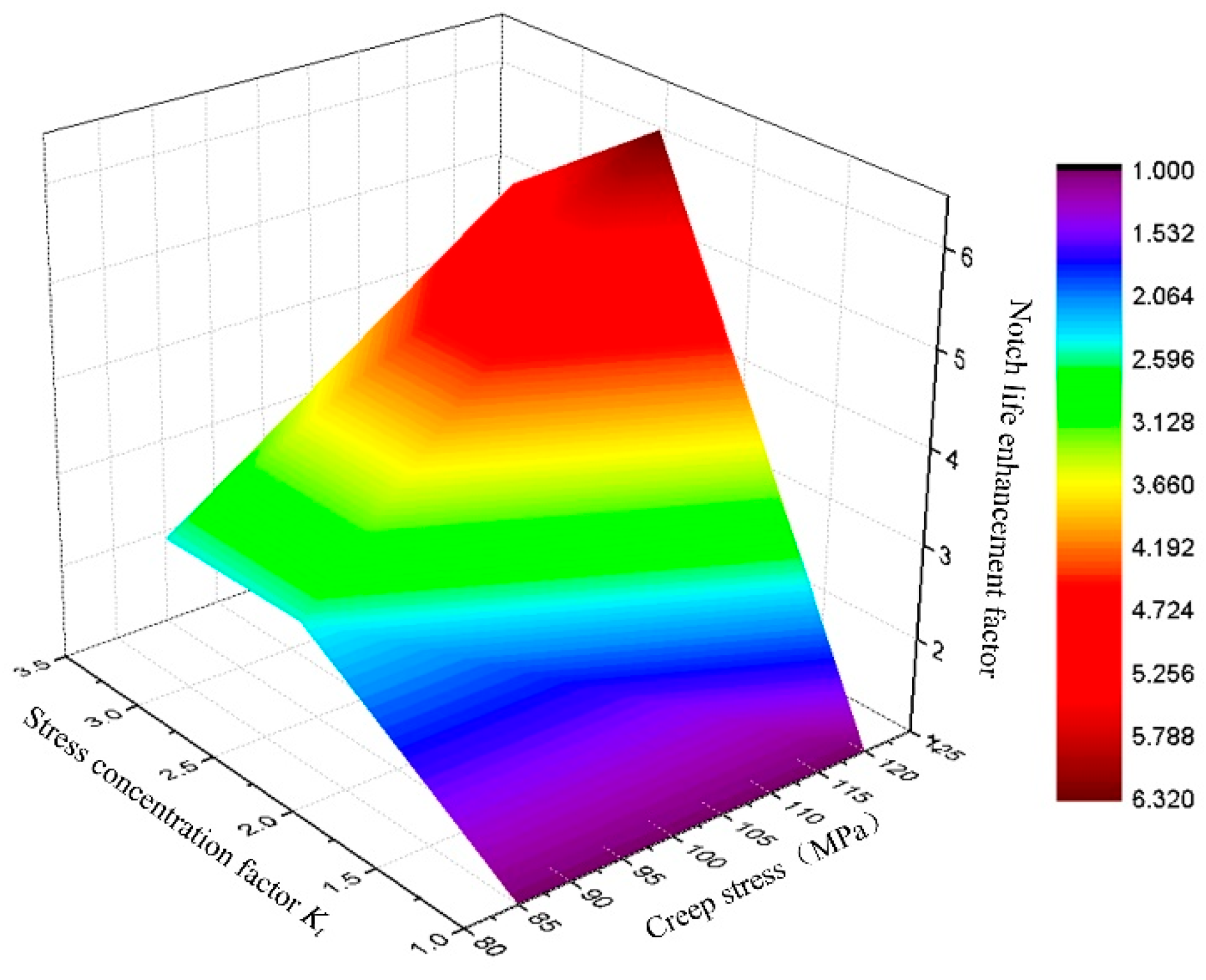

- Both stress concentration factor and the net stress collectively determined the notch life enhancement factor.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Experiments

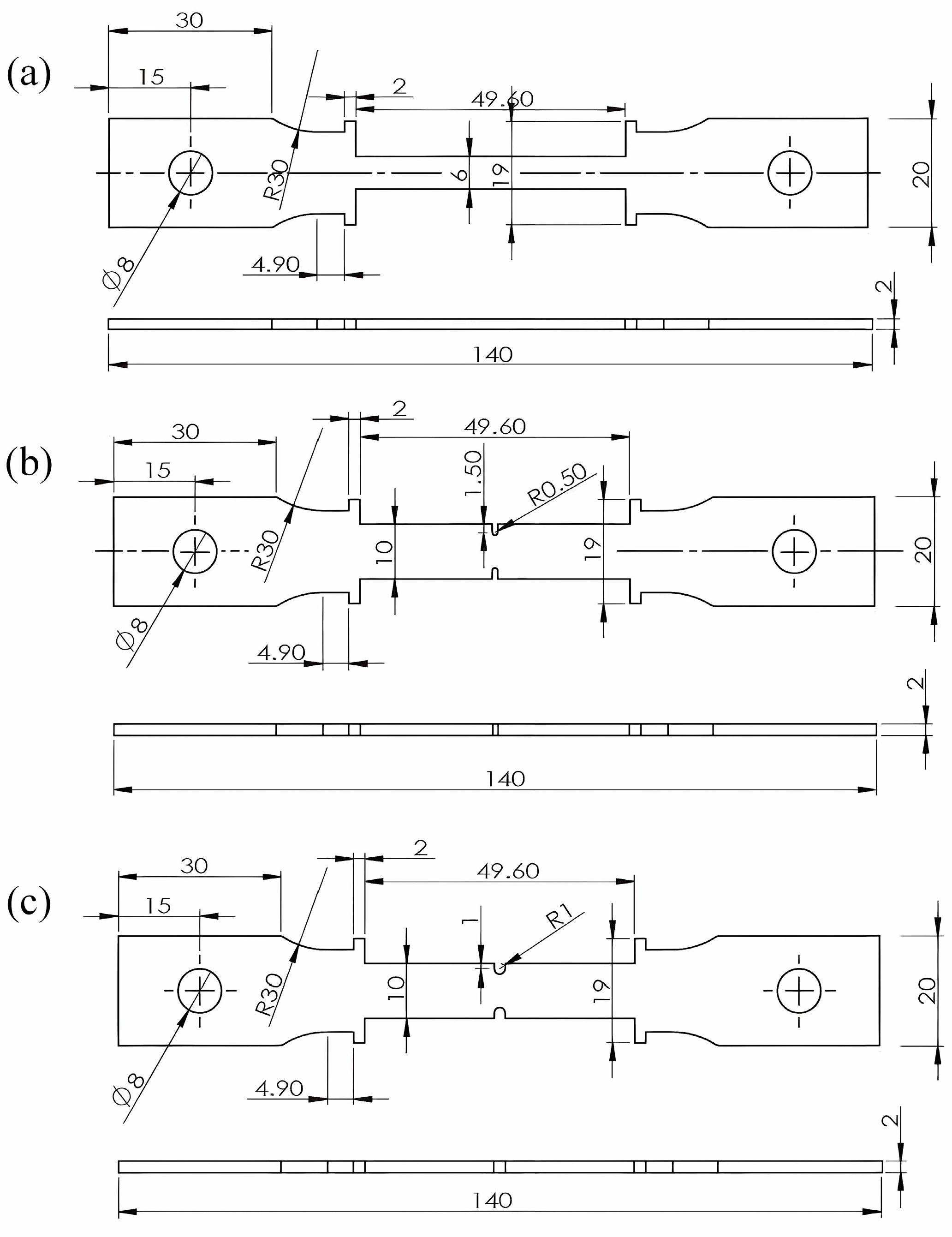

2.1. Materials and Specimens

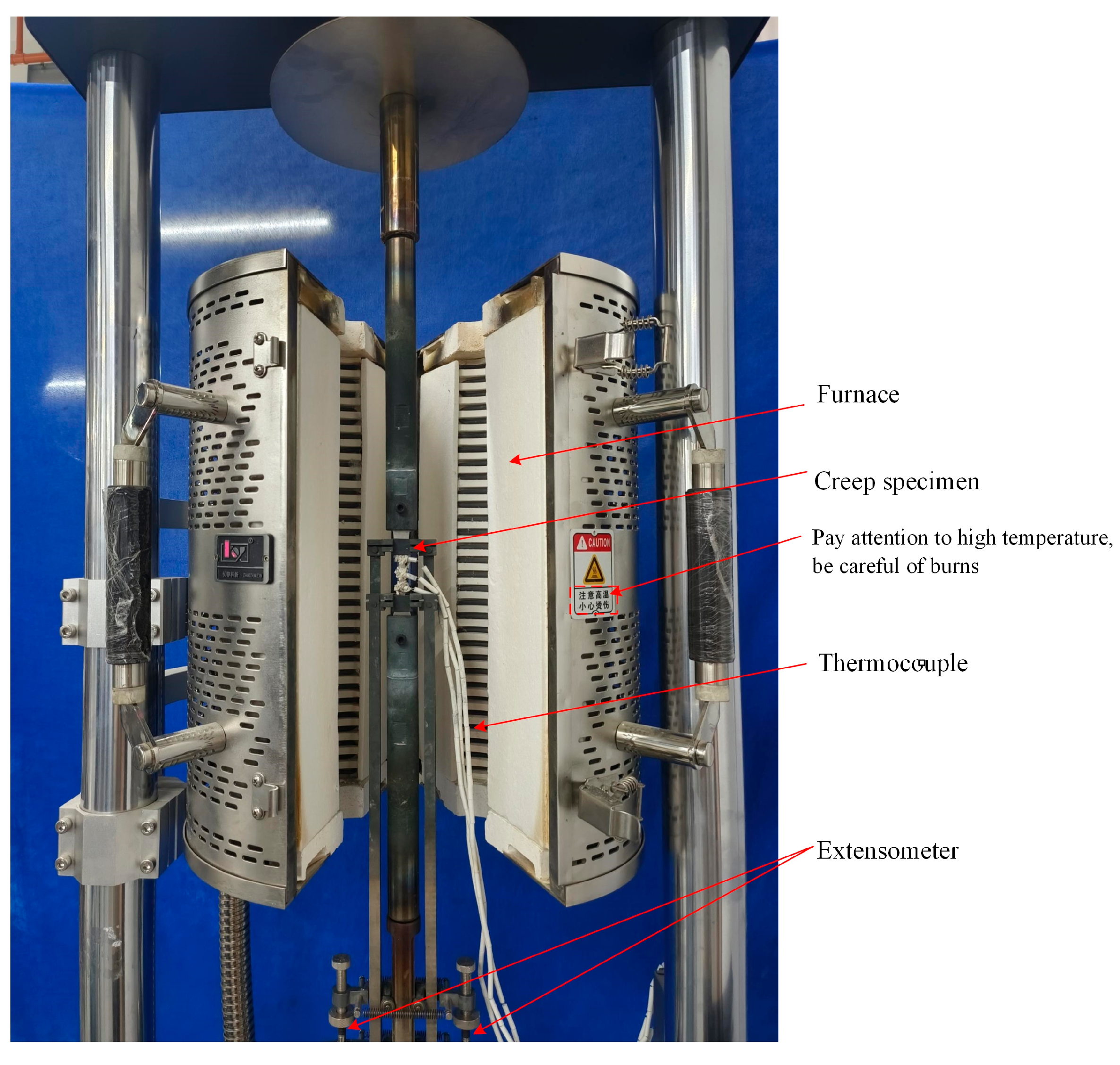

2.2. Creep Tests

3. Results and Discussion

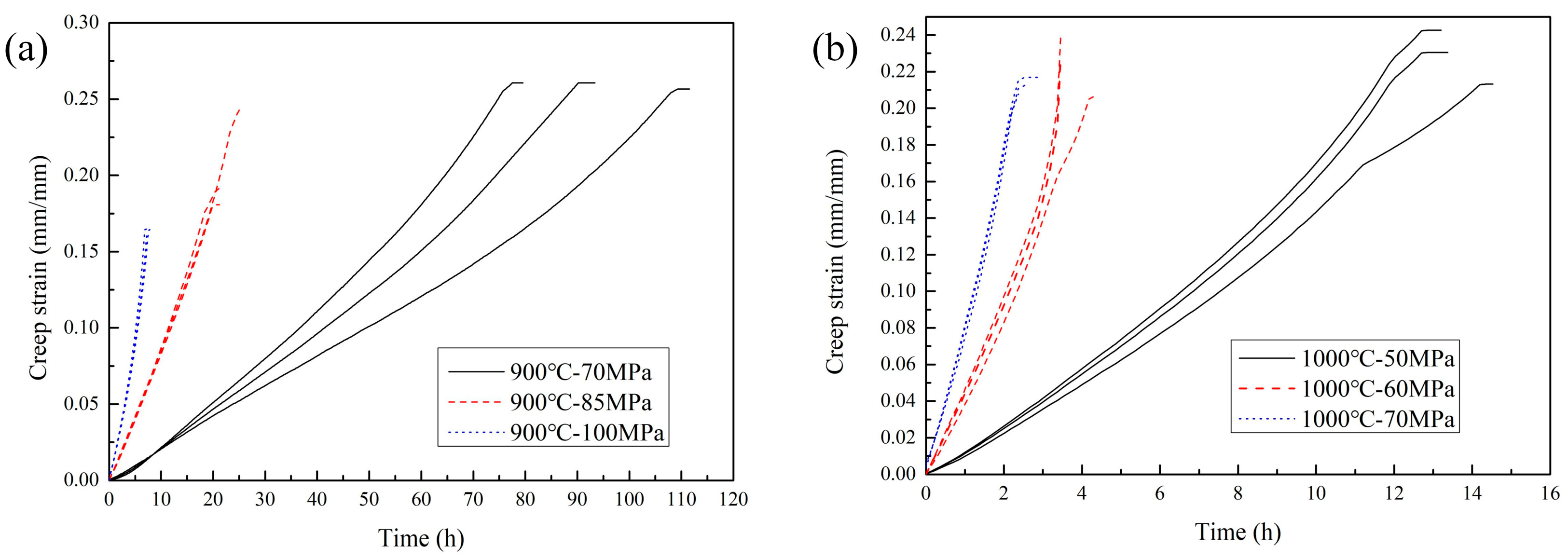

3.1. Creep Test Results

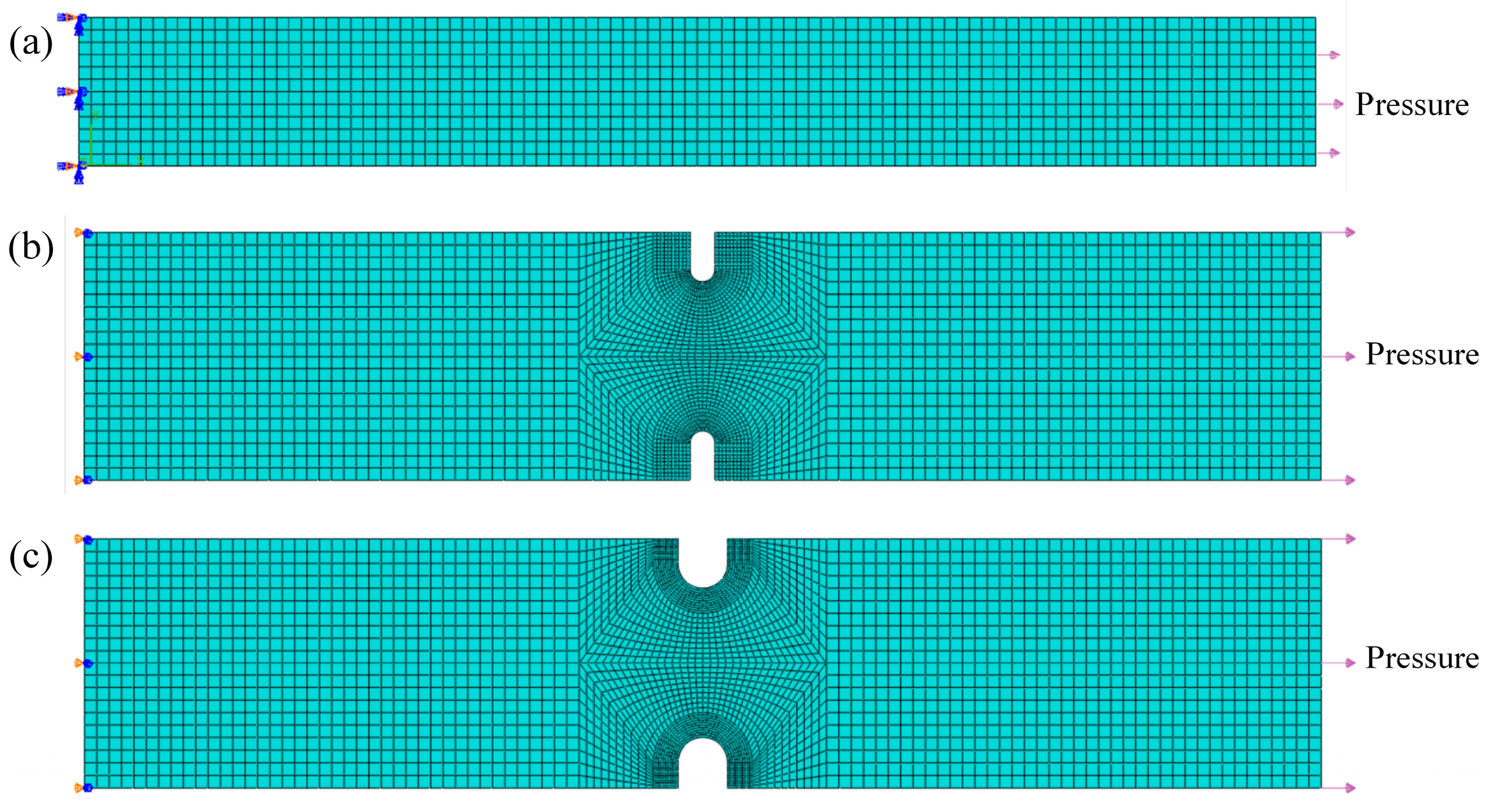

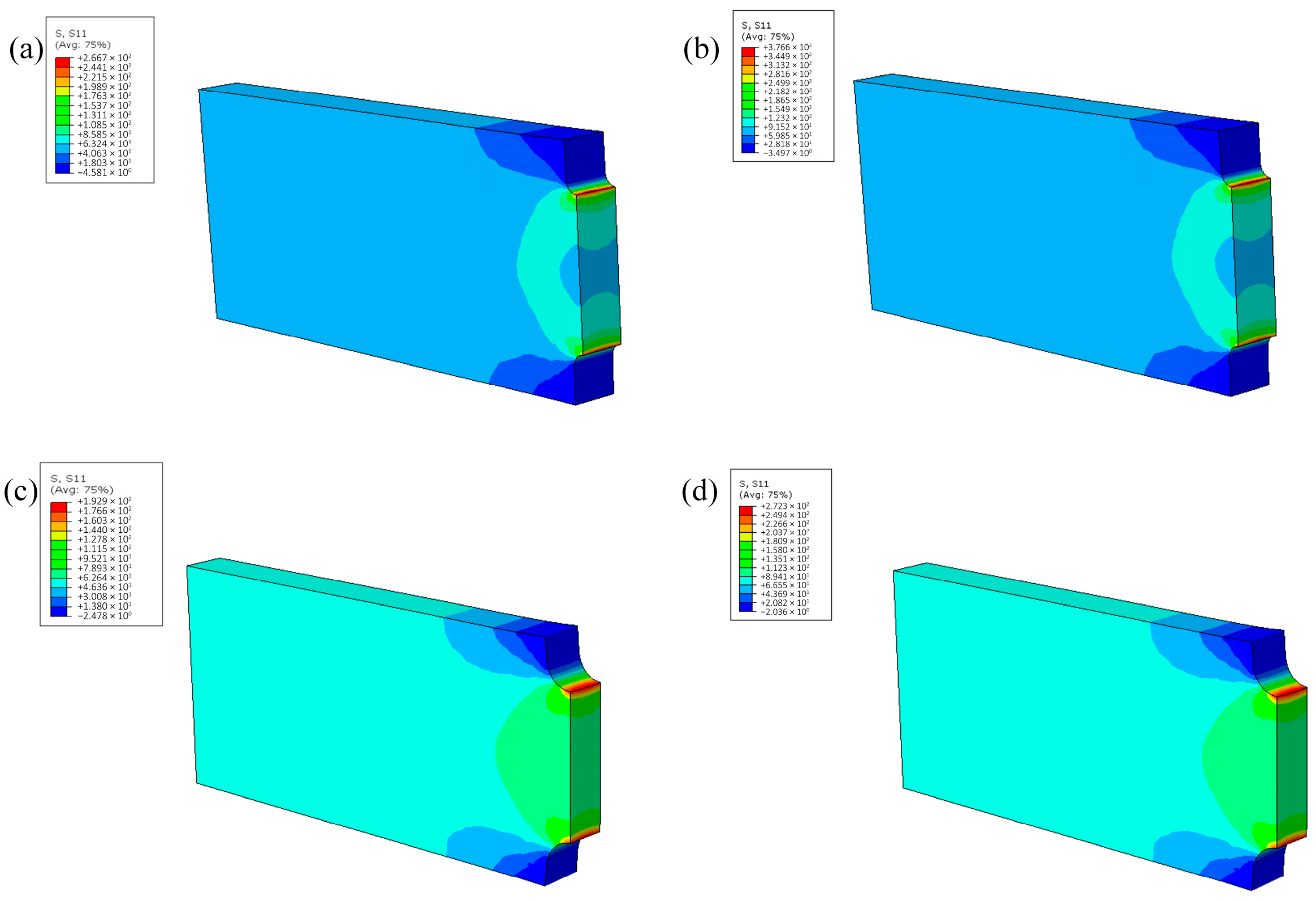

3.2. Stress Analysis of Creep Initial State

3.3. Creep Life Prediction

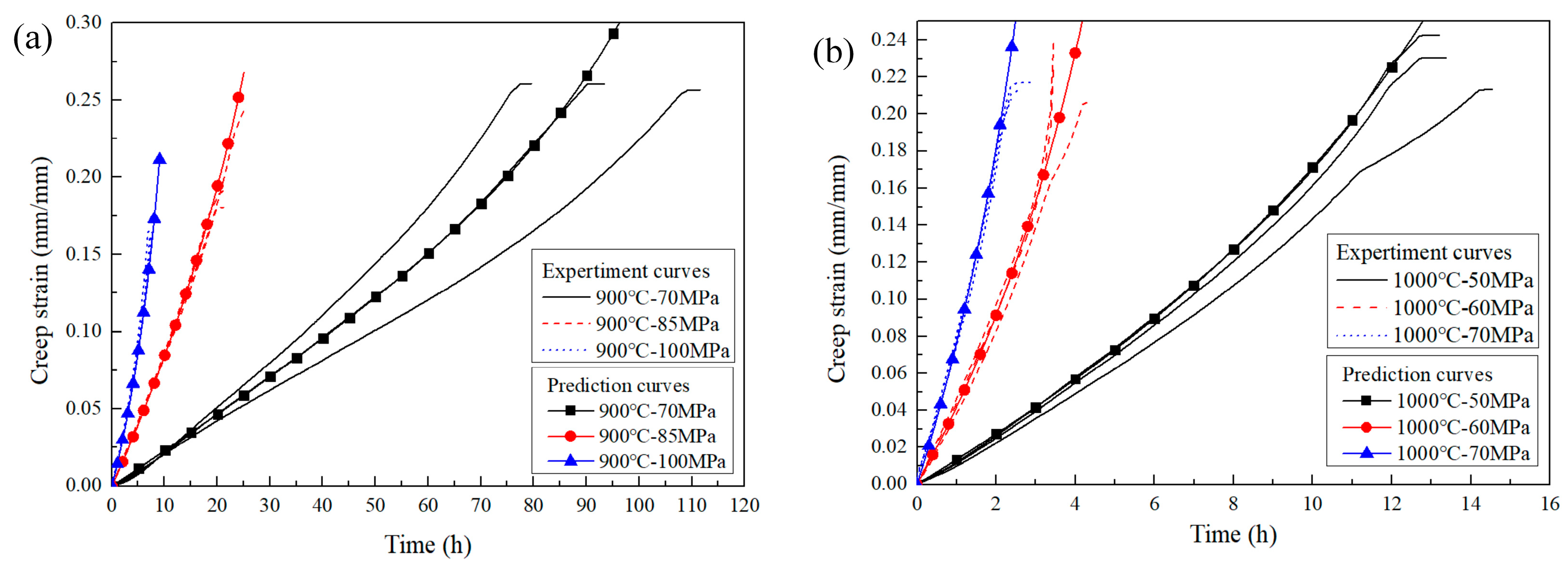

3.3.1. Prediction of Creep Strain Curves Based on θ Parameter Method

3.3.2. Creep Life Prediction for Smooth Flat Plate Specimens

3.3.3. Creep Life Prediction for Notched Specimens

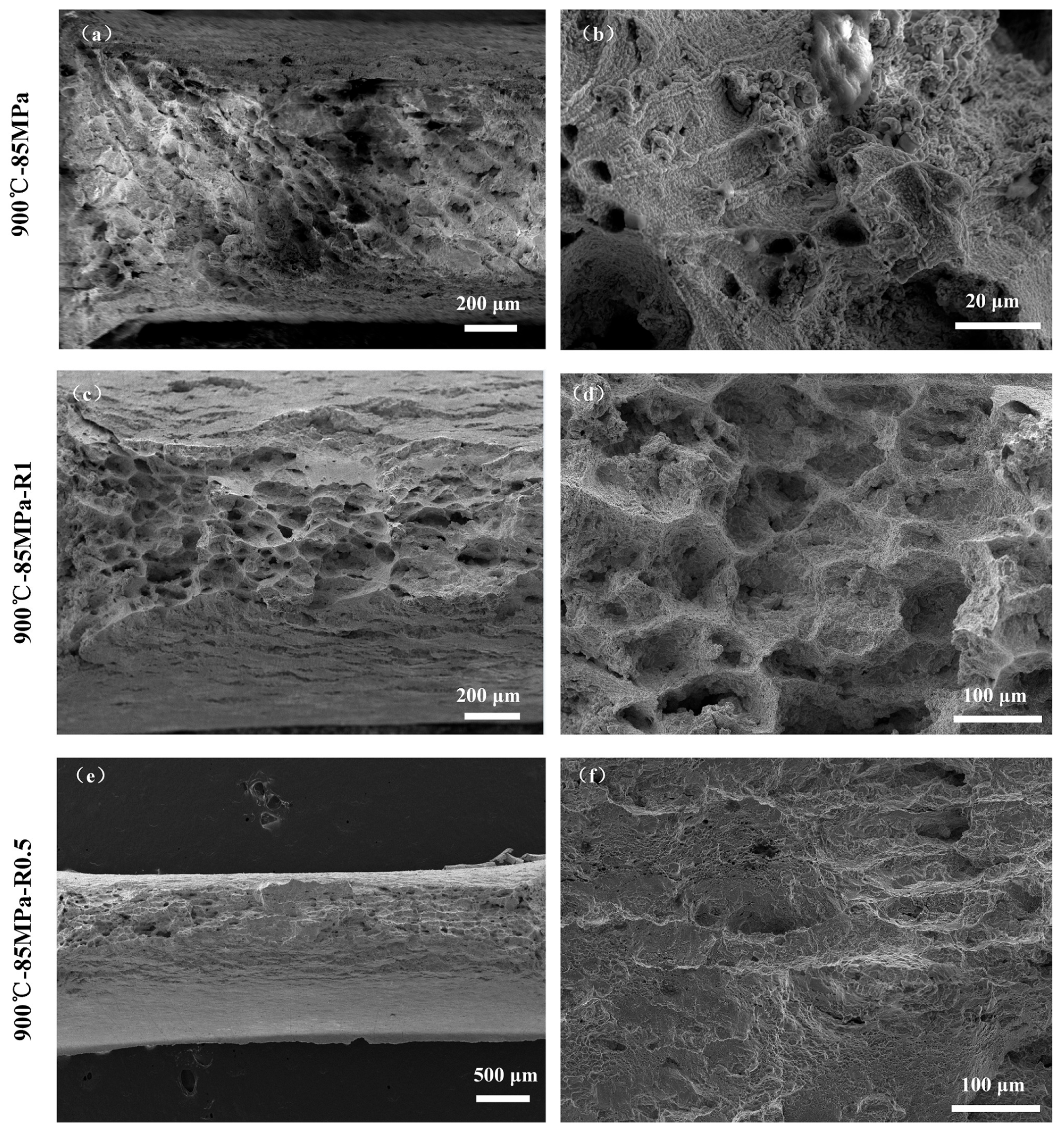

3.4. Fracture Analysis

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The creep process in smooth flat plate specimens was dominated by the secondary creep stage, whereas the notched specimens exhibited a significantly accelerated tertiary creep stage. The creep fracture strain decreased with increasing load.

- (2)

- Predictions from the θ parameter method agreed well with the experimental creep strain curves and the creep life for both smooth and notched specimens. All experimental results fell within the double dispersion band of the predictions.

- (3)

- Notches exhibited a creep life enhancing effect on GH3230 superalloy under the same net stress level. The degree of this notch life enhancement was governed by both the stress concentration factor and the applied net stress, with the effect being more pronounced at higher stress levels.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, L.S.; Shi, Z.F.; Wang, Y.C.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Li, P.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, R.; Dong, H. Strong correlation on multiscale microstructure and mechanical properties of selective laser melting fabricated GH3230-superalloy deformed at a wide temperature range. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1044, 184575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.L.; Liang, J.Y.; Long, X.J.; Zhang, N.; Chen, M.; Tang, J.; Liu, W.; Chen, L.; Yan, D.; Li, Q.; et al. Effects of heat treatment on microstructure and high-temperature tensile performance of Ni-based GH3230 superalloy processed by Laser powder bed fusion. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1021, 179619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Hou, C.; Jin, X.C.; Li, D.; Zhao, L.; Yang, L.; Fan, X. Thermal fatigue crack initiation and propagation behaviors of GH3230 nickel-based superalloy. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2024, 47, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.X.; Wen, Z.X.; Yue, Z.F. Effects of strain rate and temperature on mechanical property of nickel-based superalloy GH3230. Rare Met. Mater. Eng. 2015, 44, 2601–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.P.; Hou, C.; Ren, X.D.; Yang, J.; Jin, X.; Yang, Q.; Fan, X. Study on creep behaviors of GH3230 superalloy with side notches or a center inclined hole at 900 °C and 1000 °C. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2025, 48, 14498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, H.Q.; Wang, S.S.; Zhang, H.; Yu, H.; Shi, X.; Yang, Y.; Wen, Z.; Yue, Z. Oxidation-creep damage assessment of Ni-based single-crystal superalloy and coated system. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 260, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.J.; Yu, H.; Wang, Z.R.; Xue, H.; Zhang, F.; Wang, G.; Zhang, X.; Qu, J. Effect of solution temperature on short-term creep behavior and microstructural evolution of GH4738 Ni-based superalloy. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 49, 114207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Kim, K.M.; Jeon, Y.H.; Shin, S.; Park, J.S.; Cho, H.H. Effect of thermal stress on creep lifetime for a gas turbine combustion liner. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2015, 47, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.M.; Yun, N.; Jeon, Y.H.; Lee, D.H.; Cho, H.H.; Kang, S.-H. Conjugated heat transfer and temperature distributions in a gas turbine combustion liner under base-load operation. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2010, 24, 1939–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.S.; Li, B. Creep Notch Effect in Dd6 Ni-Based Single Crystal Superalloy: Experimental and Modeling Studies. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 931, 148221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Qin, H.J.; Li, R.H.; He, Z.; Song, J.; Fu, Z.; Lv, Y.; Sun, Y.; Ji, P.; Dai, T. Influence of loading sequence on notch creep behavior of Ni-based single crystal superalloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 939, 148472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.X.; Song, Z.Y.; Liu, H.H.; Hu, D.; Huang, D.; Yan, X.; Yan, W. A dislocation-based damage-coupled constitutive model for single crystal superalloy: Unveiling the effect of secondary orientation on creep life of circular hole. Int. J. Plast. 2024, 173, 103874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Laha, K. Creep life prediction of 9Cr–1Mo steel under multiaxial state of stress. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2014, 615, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Laha, K.; Das, C.R.; Panneerselvi, S.; Mathew, M.D. Effect of constraint on creep behavior of 9Cr-1Mo steel. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2014, 45, 619–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Laha, K.; Das, C.R.; Mathew, M.D. Analysis of creep rupture behavior of Cr-Mo ferritic steels in the presence of notch. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2015, 46, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.G.; Guo, S.S.; Gao, F.H.; Niu, T.-Y.; Xuan, F.-Z. Creep damage and interaction behavior of neighboring notches in components at elevated temperature. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2021, 256, 107996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, G.Z.; Xuan, F.Z.; Tu, S.T. Effects of creep ductility and notch constraint on creep fracture behavior in notched bar specimens. Mater. High Temp. 2016, 33, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, X.F.; Li, J.R.; Dong, J.X. China Superalloys Handbook; Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- IS0 204: 2009; Metallic Materials-Uniaxial Creep Testing in Tension Method of Test, MOD. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Brown, S.G.R.; Evans, R.W.; Wilshire, B. A Comparison of Extrapolation Techniques for Long-Term Creep Strain and Creep Life Prediction Based on Equations Designed to Represent Creep Curve Shape. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 1986, 24, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, B.F.; Gibbons, T. Tertiary creep in nickel-base superalloys: Analysis of experimental data and theoretical synthesis. Acta Metall. 1987, 35, 2355–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elements | C | Cr | Ni | Co | W | Mo | Al | Ti |

| Mass fraction/% | 0.05–0.15 | 20.00–24.00 | balance | ≤5.00 | 13.00–15.00 | 1.00–3.00 | 0.20–0.50 | ≤0.10 |

| Elements | Fe | La | B | Si | Mn | S | P | Co |

| Mass fraction/% | ≤3.00 | 0.005–0.05 | ≤0.015 | 0.25–0.75 | 0.30–1.00 | ≤0.015 | ≤0.05 | ≤0.50 |

| Temperature/°C | Elasticity Modulus E/GPa | Poisson Ratio v | Yield Strength/MPa | Tensile Strength/MPa | Thermal Expansion Coefficient α/10−6 °C−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 215 | 0.31 | 389.5 | 905~910 | / |

| 600 | 182 | 0.32 | 316.6 | 735~740 | 14.7 |

| 700 | 176 | 0.33 | 289.9 | 620~635 | 15.3 |

| 800 | 168 | 0.33 | 234.2 | 405~410 | 15.7 |

| 900 | 160 | 0.34 | 142.7 | 250~285 | 16.0 |

| 1000 | 150 | 0.35 | 71.5 | 151~157 | 16.3 |

| Temperature/°C | Notch | Net Stress/MPa | Number of Specimens |

|---|---|---|---|

| 900 | Smooth flat plate specimen | 100 | 3 |

| 85 | 3 | ||

| 70 | 3 | ||

| 1000 | Smooth flat plate specimen | 70 | 3 |

| 60 | 3 | ||

| 50 | 3 | ||

| 900 | R = 0.5 mm | 120 | 3 |

| 85 | 3 | ||

| R = 1 mm | 120 | 3 | |

| 85 | 3 | ||

| Total | 30 | ||

| Temperature/°C | Stress/MPa | θ1 | θ2 | θ3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 900 | 70 | 0.0023 | 0.0012 | 0.0443 |

| 85 | 0.0068 | 0.0126 | 0.0873 | |

| 100 | 0.0093 | 0.0217 | 0.2149 | |

| 1000 | 50 | 0.0113 | 0.0107 | 0.1872 |

| 60 | 0.0281 | 0.0245 | 0.4448 | |

| 70 | 0.0440 | 0.0370 | 0.6300 |

| θ | ai | bi | ci | di |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| θ1 | −10.729 | 0.00574 | −0.09642 | 0.00010 |

| θ2 | −33.419 | 0.02363 | 0.20371 | −0.00014 |

| θ3 | −4.5575 | 0.00164 | −0.16337 | 0.00016 |

| Temperature/°C | Net Stress/MPa | /h−1 | tr/h | C | n | εr | tf/h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 900 | 70 | 0.0023 | 92.8 | 4.66 | 4.21 | 0.25 | 86.6 |

| 85 | 0.0079 | 22.0 | 5.79 | 4.21 | 0.22 | 22.0 | |

| 100 | 0.0139 | 7.3 | 9.83 | 4.21 | 0.16 | 7.6 | |

| 1000 | 50 | 0.0133 | 12.9 | 5.87 | 4.25 | 0.22 | 11.9 |

| 60 | 0.0390 | 3.7 | 6.92 | 4.25 | 0.20 | 3.6 | |

| 70 | 0.0673 | 2.4 | 6.32 | 4.25 | 0.21 | 2.2 |

| Stress/MPa | Notch Radius/mm | Life/h | Stress Concentration Factor Kt | Notch Life Enhancement Factor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 85 | R = 1 | 54.71 | 2.27 | 2.489 | 2.485 |

| 85 | R = 0.5 | 54.53 | 3.13 | 2.481 | |

| 120 | R = 1 | 11.20 | 2.27 | 6.32 | 5.71 |

| 120 | R = 0.5 | 9.03 | 3.13 | 5.1 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, H.; Cheng, D.; Chen, M.; Xiao, W.; Hou, C. Research on Creep Behaviors of GH3230 Superalloy Sheets with Side Notches. Materials 2025, 18, 5509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245509

Zhao H, Cheng D, Chen M, Xiao W, Hou C. Research on Creep Behaviors of GH3230 Superalloy Sheets with Side Notches. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245509

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Honghua, Dingnan Cheng, Minmin Chen, Wei Xiao, and Cheng Hou. 2025. "Research on Creep Behaviors of GH3230 Superalloy Sheets with Side Notches" Materials 18, no. 24: 5509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245509

APA StyleZhao, H., Cheng, D., Chen, M., Xiao, W., & Hou, C. (2025). Research on Creep Behaviors of GH3230 Superalloy Sheets with Side Notches. Materials, 18(24), 5509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245509