Influence of Alkaline Electrolyzed Water on the Strength, Shrinkage Behavior, and Microstructure of Alkali-Activated Fly Ash/Slag Composites

Abstract

1. Introduction

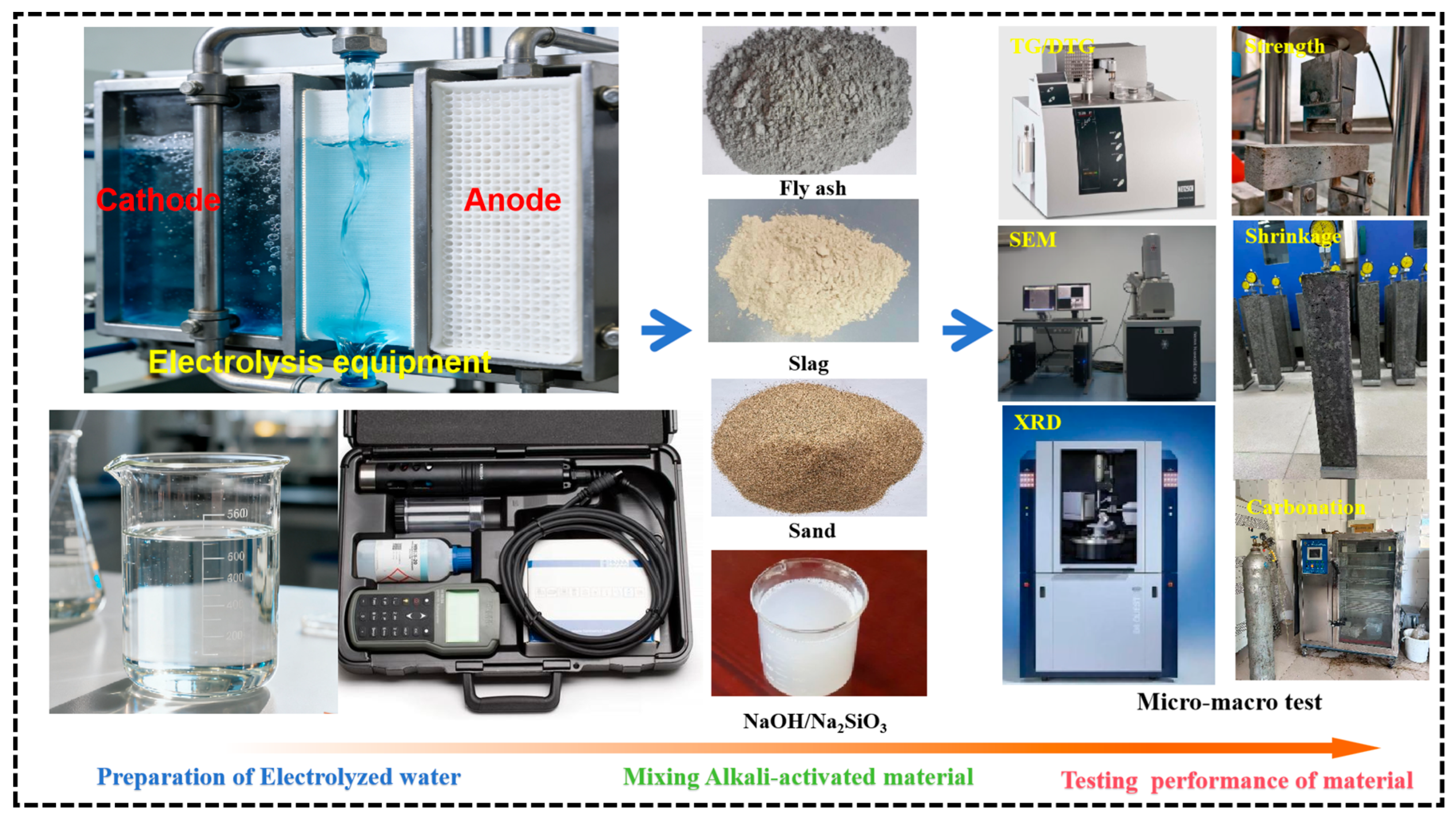

2. Experimental Program

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.1.1. Mineral Admixtures

2.1.2. Alkaline Activator

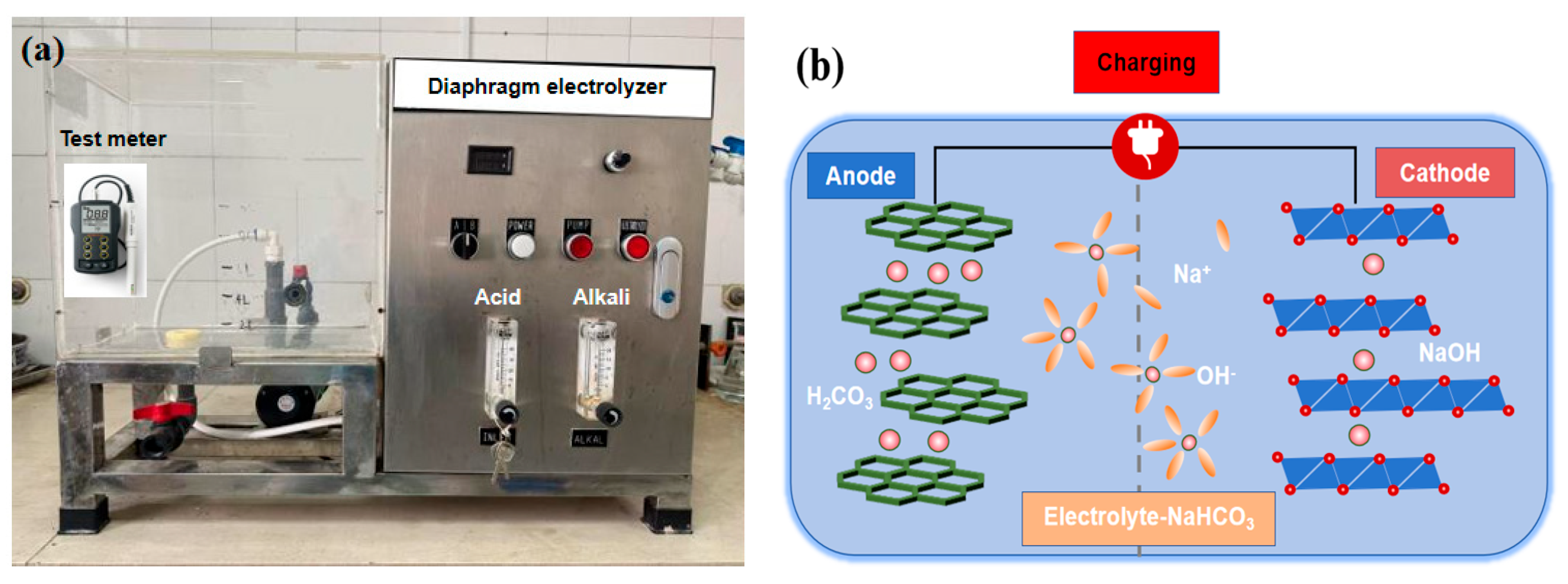

2.1.3. Alkaline Electrolyzed Water (AEW)

2.1.4. Fine Aggregate

2.1.5. Water-Reducing Admixture

2.2. Mix Proportion Design of Alkaline-Activated Material

2.3. Experimental Methods

3. Results and Discussion

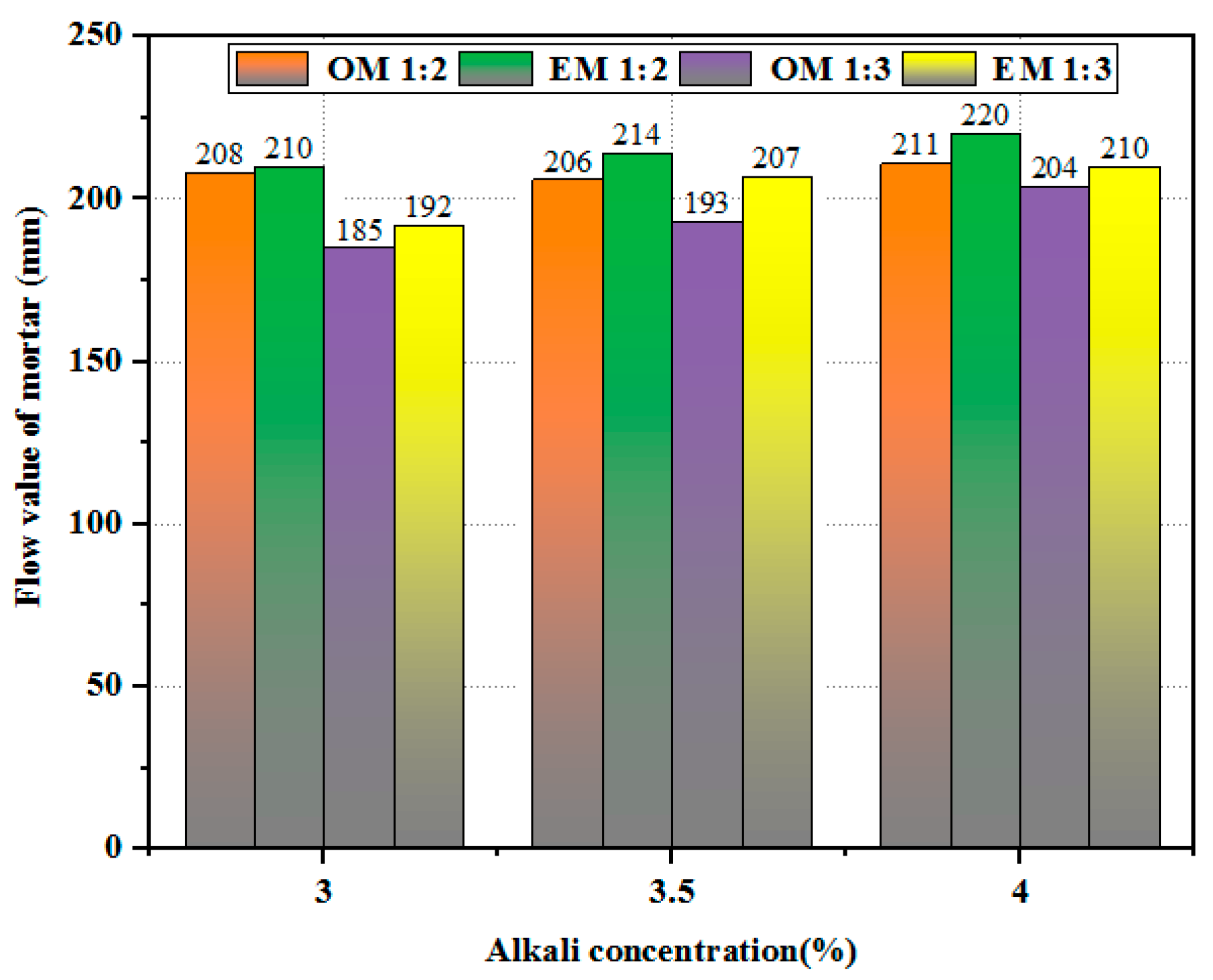

3.1. Workability of AEW-Based Alkali-Activated Composites

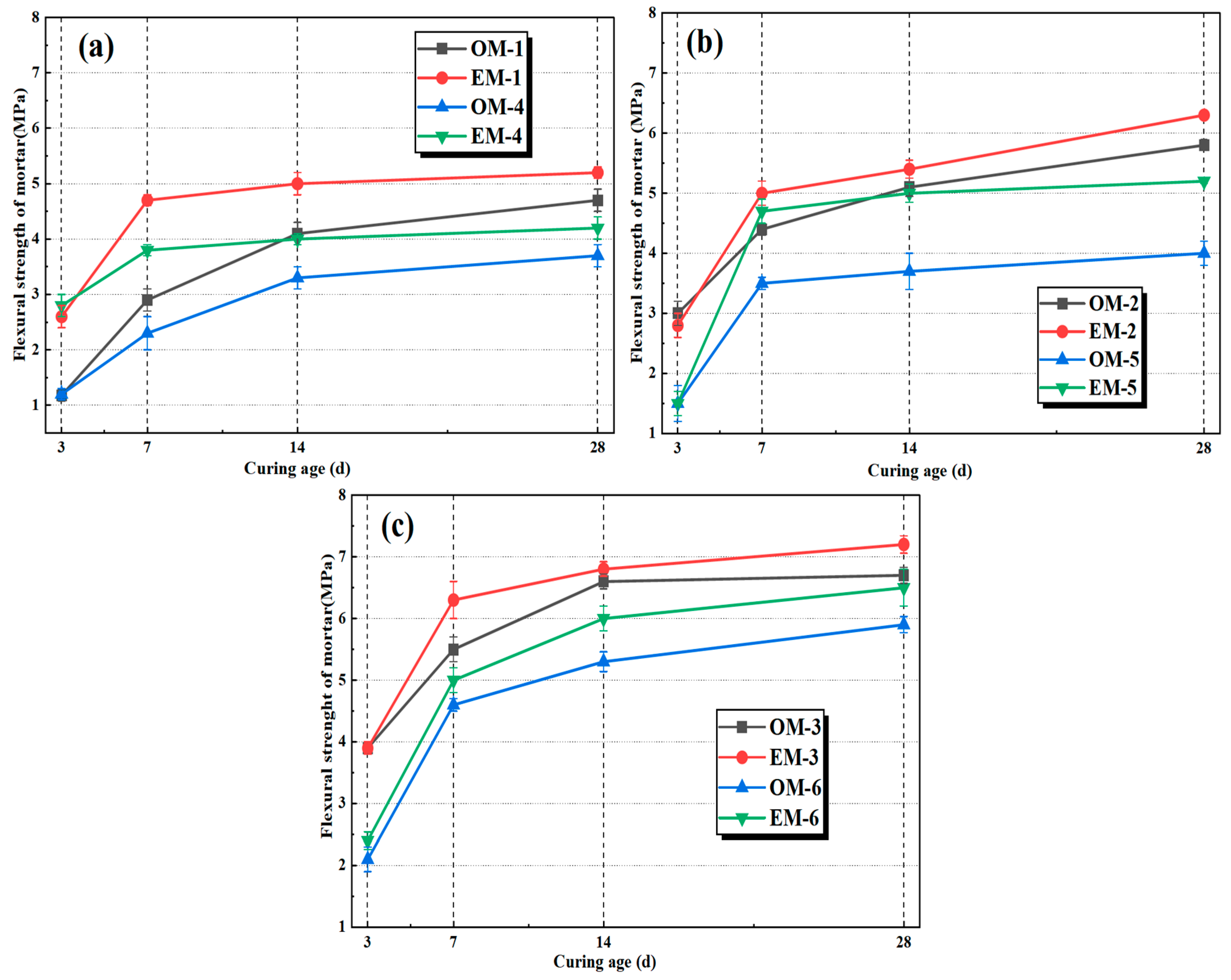

3.2. Flexural Strength of AEW-Based Alkali-Activated Composites

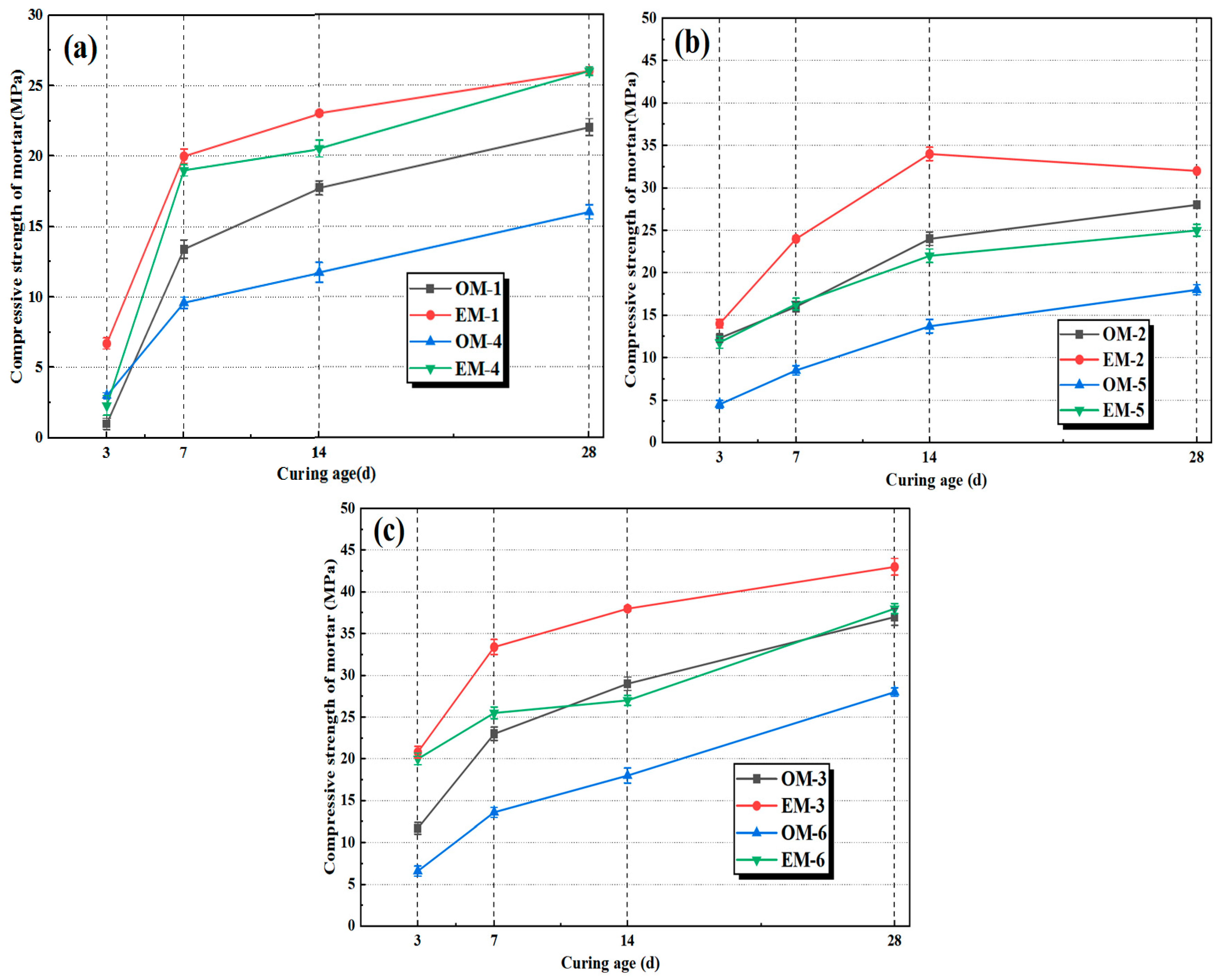

3.3. Compressive Strength of AEW-Based Alkali-Activated Composites

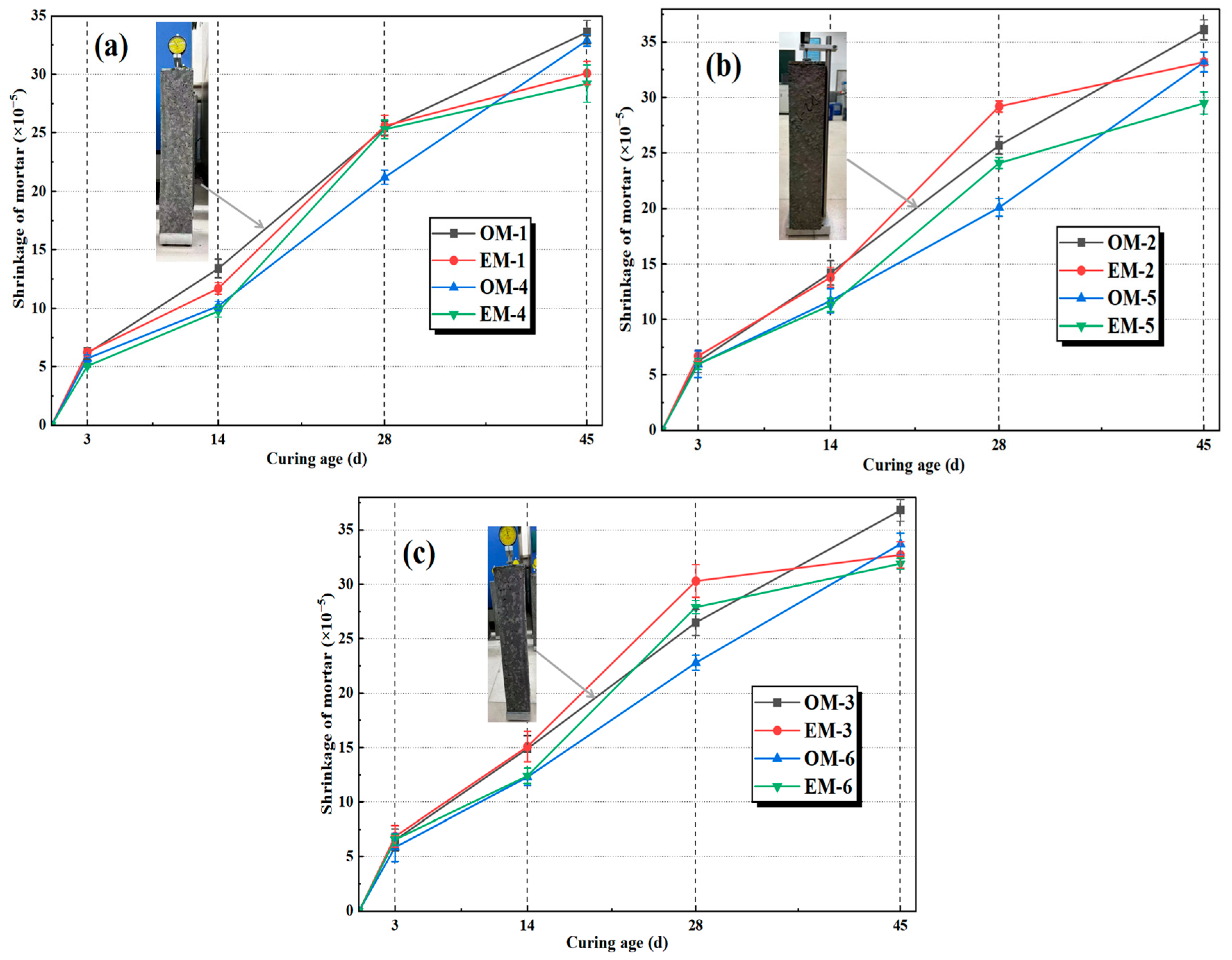

3.4. Shrinkage of AEW-Based Alkali-Activated Composites

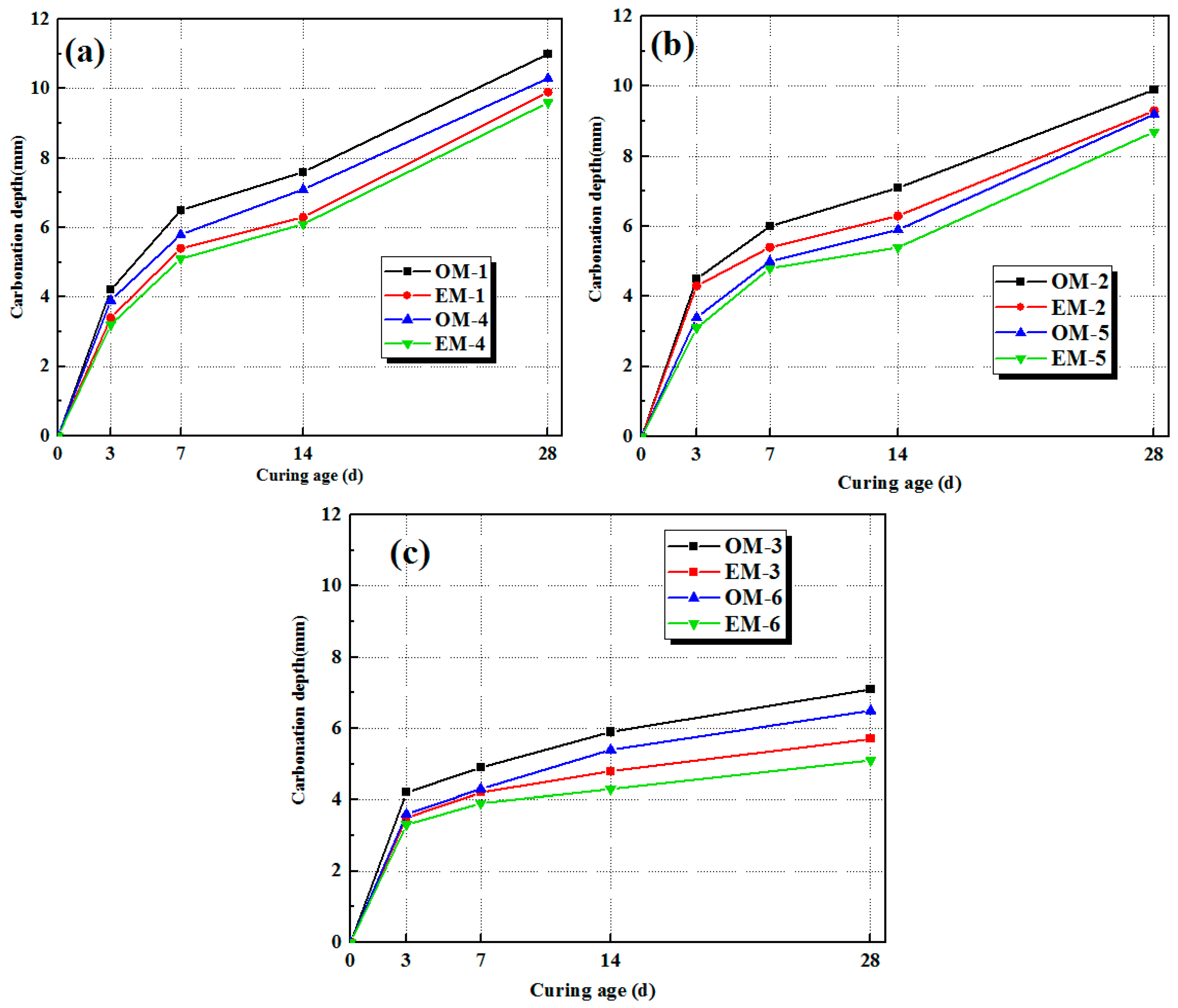

3.5. Carbonation of AEW-Based Alkali-Activated Composites

3.6. Microscopic Properties of AEW-Based Alkali-Activated Composites

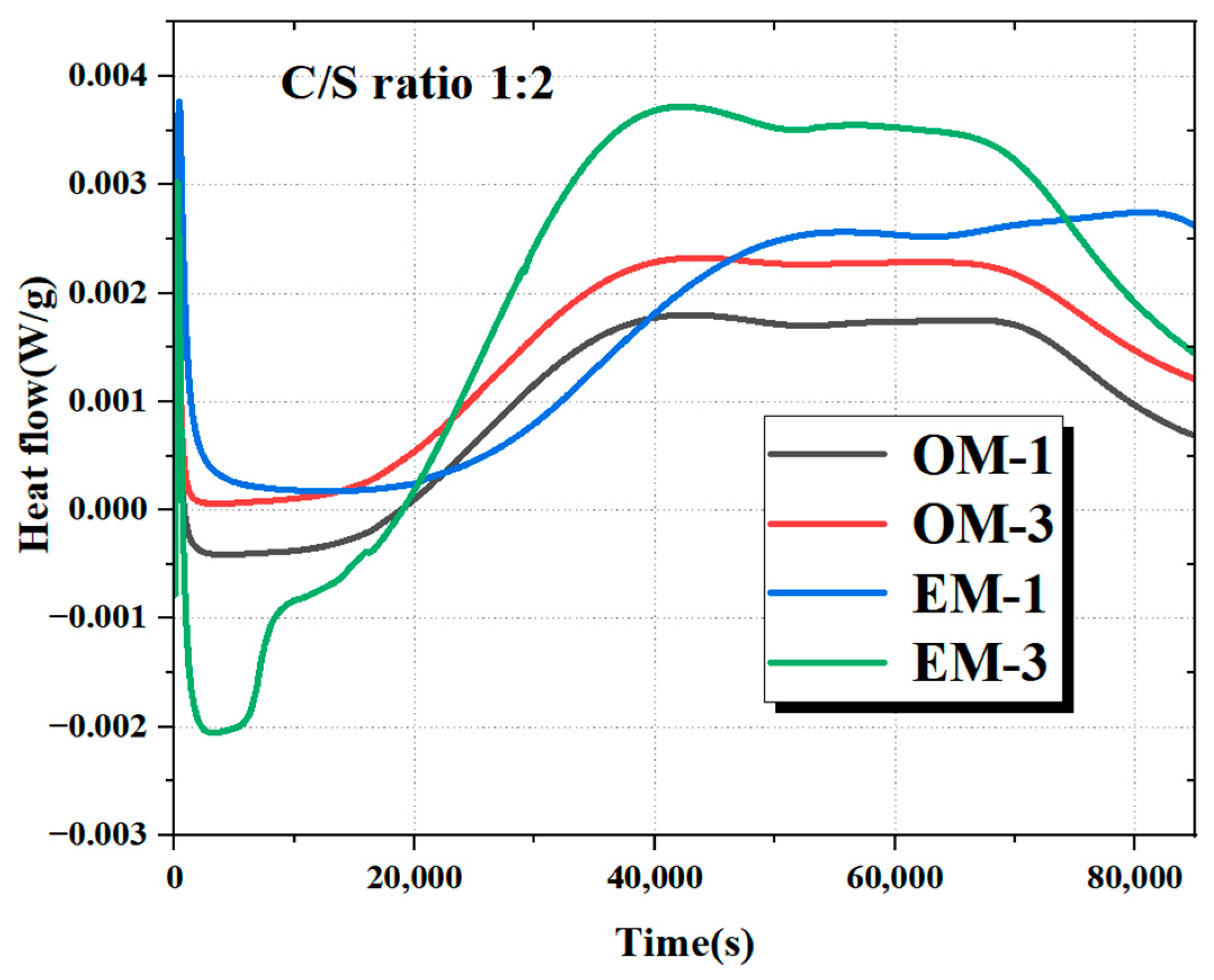

3.6.1. Alkali Activation Reaction Characteristics

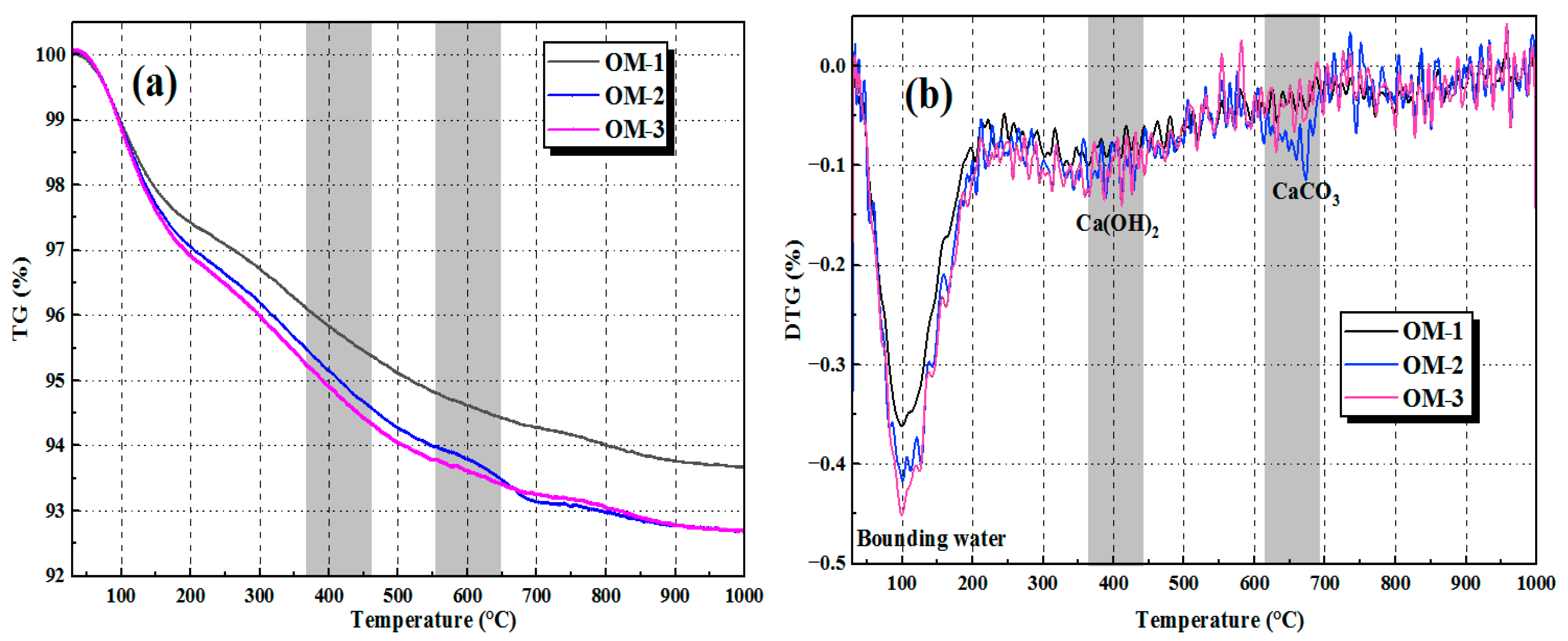

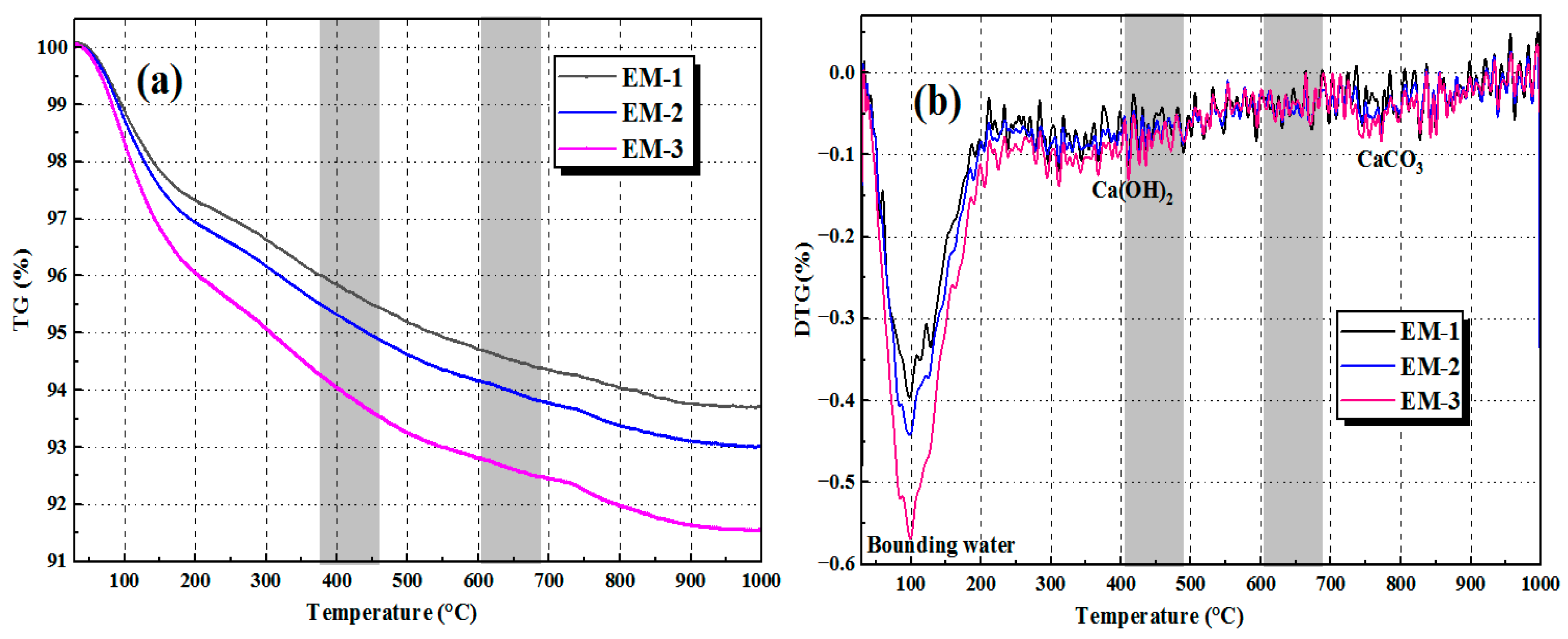

3.6.2. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TG/DTG)

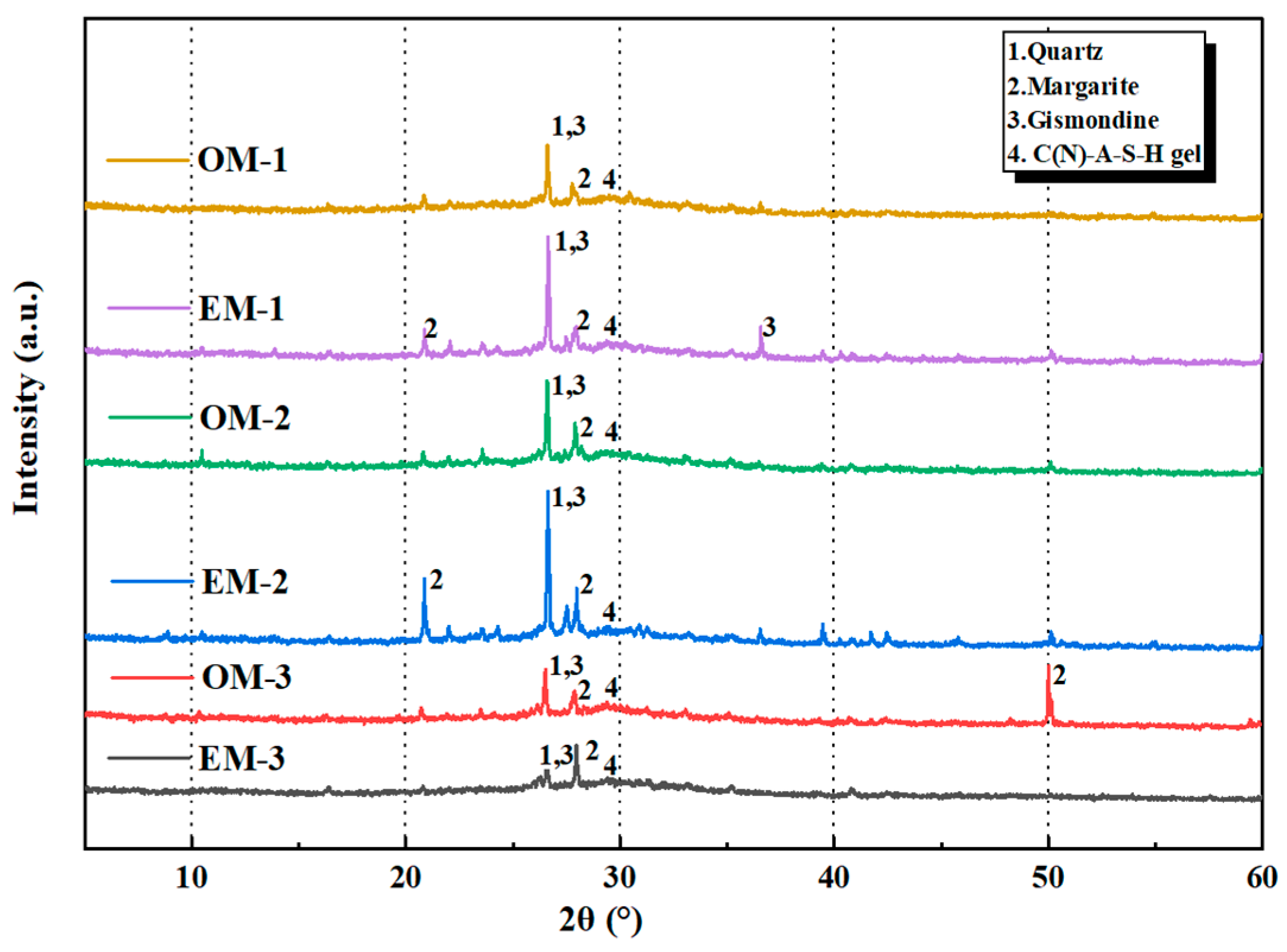

3.6.3. XRD Analysis

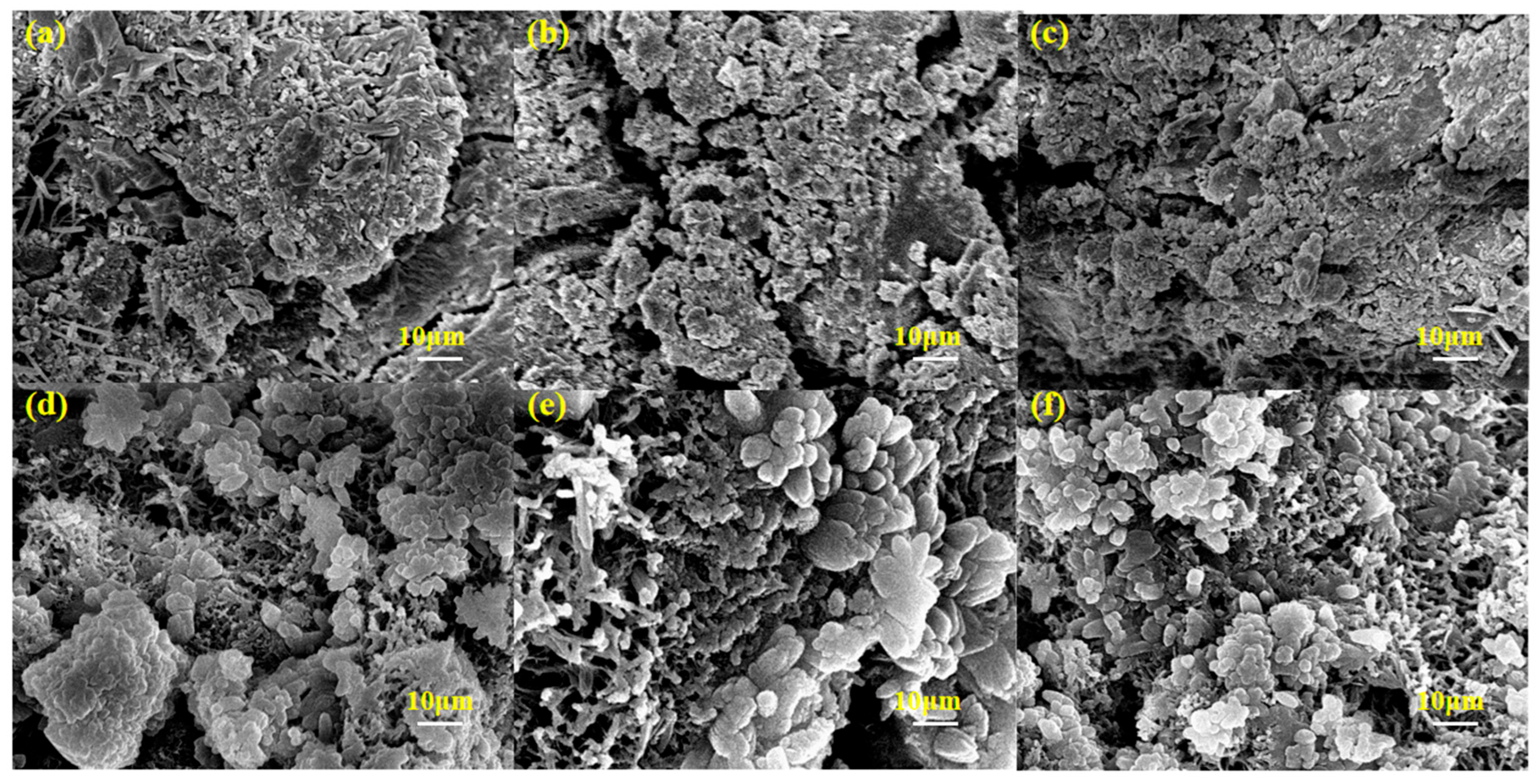

3.6.4. SEM Microscopic Morphology

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Highly active alkaline electrolyzed water can enhance the mechanical properties of alkali-activated fly ash/slag mortar (AAFSM). At the same alkali concentration, the EM group outperforms the OM group in both compressive and flexural strengths. The EM mortar at an alkali concentration of 4.0% achieves the optimal performance, and 28 d compressive and flexural strength increased by 13.5% and 7.5%, respectively. The 28 d drying shrinkage rate of the EM group is reduced by 7.4–11.2% more than the OM group.

- (2)

- AEW promotes the alkali activation reaction process and optimizes the microstructure of AAFSM. TG/DTG results show the EM group has higher bound water mass loss and lower Ca(OH)2/CaCO3 mass loss. XRD analysis confirms the EM group has stronger N-A-S-H/C-A-S-H gel peaks and weaker peaks of unreacted minerals, verifying a more adequate alkali activation reaction.

- (3)

- A critical finding is that 4.0% alkali concentration maximizes AEW’s activation efficacy, balancing strength improvement and shrinkage inhibition. This concentration maximizes the acceleration of silicon–aluminum component dissolution in fly ash and slag by AEW’s high ion activity, promotes the formation of high-quality N-A-S-H/C-A-S-H gels, and constructs a dense microstructure, thereby comprehensively improving the strength, shrinkage resistance, and durability of AAFSM.

- (4)

- This study validated AEW as a high-efficiency, eco-friendly activator for alkali-activated materials (AAMs), addressing the need for performance enhancement of solid waste-based AAMs and advancing low-carbon construction materials. However, this study focuses on mortar under standard conditions; future research will further optimize AEW preparation parameters to extend AEW’s application to alkali-activated concrete with other industrial solid wastes to broaden its sustainability value.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kang, I.; Kim, G.; An, T.; Lee, J.; Shin, S.; Kim, J. Carbon neutrality in the Korean cement industry: Reducing carbon emissions by increasing supplementary cementitious material content in ordinary Portland cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 494, 143391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellet-Plamondon, C.; Habert, G. 25-Life cycle assessment (LCA) of alkali-activated cements and concretes. In Handbook of Alkali-Activated Cements, Mortars and Concretes; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2015; pp. 663–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Zhang, H.; Deng, T.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, T.; Corr, D. Experimental and theoretical investigation of low-shrinkage alkali-activated materials permanent formwork reinforced concrete prisms under axial load. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 500, 144156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wu, J.; Song, N.; Zheng, Y.; Lu, Y.; Chi, Y. Time-dependent drying shrinkage model for alkali-activated slag/fly ash-based concrete modified with multi-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 111, 113082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Bao, L.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, R.; Li, G.; Cui, J. The mechanical properties, shrinkage mitigation, and bond performance of recycled powder based alkali-activated paste for surface enhancement of recycled concrete aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 486, 141993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Wei, H.; Liu, G.; Gao, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, K. Nano-silica modified alkali activated multi-solid waste concrete: Mechanisms of hydration and seawater corrosion. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 492, 142884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, S.; Huang, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Shi, Y. Carbonation performance and environmental assessment of alkali-activated slag-fly ash-steel slag mortars: Precursor composition effects revealed by quantitative carbonate zoning. Environ. Res. 2025, 288, 123252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Li, S.; Su, M.; Feng, J. Research on thermoelectric seebeck effect and water-ion interaction mechanism of alkali-activated fly ash/slag materials. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 113, 114082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Z.; Lu, Z. Influence of fly ash content on pore structure regulation in alkali-activated slag under alkaline conditions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 485, 141863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, L.; Souza, M.; Melo, A.; Costa, H.; Babadopulos, L.; Cabral, A.; Pileggi, R. High-strength self-compacting alkali-activated concrete produced with fly ash and steel slag: Rheological behavior and mixing rheology comparisons with a Portland cement concrete. Cement 2025, 22, 100156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Li, S.; Lei, Z.; Wu, J.; Yuan, X.; Feng, J. Research on the conductivity characteristics and water-ion interaction mechanism of alkali-activated fly ash-slag. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 112, 113915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, D.; Li, B.; Li, S.; Tian, W.; Ouyang, X.; Yao, Z.; Niu, K.; et al. Alkali-activated ternary cementitious materials with ground granulated blast furnace slag, fly ash, and desert sand: Hydration property, drying shrinkage, and pore structure. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 114, 114311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wu, M.; Shen, W.; Zhou, M.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, W.; Ye, J.; Zhang, B.; Li, J.; Wang, G. Optimization of mix design and hydration mechanism of the sodium hydroxide/sodium carbonate alkali-activated slag-fly ash cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 491, 142747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, S.; Zheng, D.; Ren, J.; Bu, Y.; Pang, X. The excellent adaptability to large temperature differences of alkali-activated slag using Na2SO4+ Ca(OH)2 as the activator. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 431, 136514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Tang, D.; Yang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Q.; Pan, Q.; Yang, C. Effect of Ca(OH)2 on shrinkage characteristics and microstructures of alkali-activated slag concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 175, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Gawwad, H.; Hirsch, T.; Lehmann, C.; Stephan, D. High early strength alkali-activated mortar from artificial slag blended with high-volume limestone powder: Reaction kinetics and thermodynamic modeling. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 161, 106108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jin, Z.; Liu, G.; Dong, W.; Pang, B.; Ding, X. Mechanisms of chloride transport in low carbon marine concrete: An alkali-activated slag system with high limestone powder. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 72, 106539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, J.; Hu, J.; Fu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H. Chloride diffusion in alkali-activated fly ash/slag concretes: Role of slag content, water/binder ratio, alkali content and sand-aggregate ratio. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 261, 119940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Fan, C.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, X.; Liang, S.; Wang, X. Effect of magnetization conditions on the slump and compressive strength of magnetized water concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshta, M.; Elshikh, M.; Kaloop, M.; Hu, J.; ELMohsen, I. Effect of magnetized water on characteristics of sustainable concrete using volcanic ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 361, 129640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Feng, M.; Li, M.; Tian, D.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, G. Enhancing the carbonation and chloride resistance of concrete by nano-modified eco-friendly water-based organic coatings. Mater. Commun. 2023, 37, 107284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Shu, F.; Yan, S.; Shi, B.; Yao, K.; Dong, Q. Design, preparation, and performance of a nano-modified organic-inorganic composite hydrophobic surface treatment agent for concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 496, 143821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Yue, G.; Guo, Y.; Xie, Z.; Li, Q.; Chen, M.; Wang, L. Development of different alkaline electrolysed water on early strength enhancement and hydration acceleration of cement based materials. Mater. Lett. 2023, 349, 134891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Su, D.; Liu, C.; Yue, G.; Guo, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, M.; Wang, L. The adaptability of polycarboxylate superplasticizer in alkaline electrolyzed water (AEW)-based cement composites containing clay: Workability and mechanical properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 444, 137872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumit, C.; Romio, M.; Subrata, C.; Guadagnini, M.; Pilakoutas, K. Chemical attack and corrosion resistance of concrete prepared with electrolyzed water. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 11, 1193–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Wang, M.; Chen, J.; Wang, F.; Li, Y.; Yue, G.; Guo, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, M.; Wang, L. Preparation and application of a novel alkaline electrolyzed water for the adsorption resistance of superplasticizer and rapid hydration in cement composites. Mater. Lett. 2023, 331, 133470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romio, M.; Sumit, C.; Prasanta, C.; Chakraborty, S. Development of the electrolyzed water based set accelerated greener cement paste. Mater. Lett. 2019, 243, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Meng, X.; Shang, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, R.; Song, H. Molecularly engineered phenazine-piperidone anion exchange membranes for high-performance alkaline water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 191, 152328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmig, R.; Gillemot, P.; Kretschmer, A.; Günther, K.; Baltruschat, H.; Witzleben, S. Challenges in the determination of reactive oxygen species evolving during membrane water electrolysis for in situ ozone production. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 64, 105623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swathi, B.; Vidjeapriya, R. Stimulation of calcium (Sodium)-alumina-silicate-hydrate (C(N)-A-S-H) gel by nano-alumina in the cleaner production of agro-based alkali-activated concrete. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2025, 46, 102100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Guan, L.; He, C.; Shi, X.; Wang, L.; Tao, H.; Liu, C.; Chi, L.; Zhu, Y.; Wen, X.; et al. Utilization of corn stover ash in alkali-activated slag pastes: Impact on mechanical; Shrinkage and hydration properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 481, 141665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zheng, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, X.; Rao, F.; Zhong, L. Durability of alkali-activated materials with different C-S-H and N-A-S-H gels in acid and alkaline environment. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 16, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Wang, E.; Li, Z.; Shi, X. Ultrafine rice husk ash in alkali-activated slag systems: Synergistic modulation of Si/Ca and Si/Al ratios to improve mechanical performance and dimensional stability. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 492, 142969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Zhang, S.; Banthia, N. Interpreting the early-age reaction process of alkali-activated slag by using combined embedded ultrasonic measurement, thermal analysis, XRD, FTIR and SEM. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 186, 107840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Ma, C.; Wu, D.; Xu, L.; Zhao, F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, M.; Chen, M. pH-dependent performance of alkaline electrolyzed water concrete: A comprehensive analysis of strength, durability, and microstructural evolution. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 37, 760–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical Composition | CaO | Al2O3 | SO3 | SiO2 | MgO | Fe2O3 | TiO2 | Na2O | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fly ash | 2.56 | 29.71 | 0.37 | 56.49 | 1.48 | 4.33 | 1.75 | 0.48 | 2.83 |

| Blast furnace slag | 38.32 | 12.28 | 1.14 | 32.07 | 7.64 | 0.47 | 1.63 | 0.25 | 6.20 |

| Performance Parameters | Ordinary Tap Water | Acid Electrolyzed Water | Alkaline Electrolyzed Water |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH value | 7.8 | 6.7 | 10.0 |

| ORP value (oxidation–reduction potential) | 317 | 353 | −226 |

| TDS (mg/L) | 69 | 30 | 107 |

| Cementitious- Sand Ratio | Alkali Concentration (%) | Mark | Slag (kg/m3) | Fly Ash (kg/m3) | Sand (kg/m3) | NaOH (kg/m3) | Water Glass (kg/m3) | Water (kg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:2 | 3.0 | OM-1 | 480 | 120 | 1200 | 16.1 | 64.4 | 279.5 |

| 3.5 | OM-2 | 480 | 120 | 1200 | 18.8 | 75.2 | 266 | |

| 4.0 | OM-3 | 480 | 120 | 1200 | 21.5 | 85.9 | 252.6 | |

| 1:3 | 3.0 | OM-4 | 400 | 100 | 1500 | 13.4 | 53.7 | 232.9 |

| 3.5 | OM-5 | 400 | 100 | 1500 | 15.7 | 62.6 | 221.7 | |

| 4.0 | OM-6 | 400 | 100 | 1500 | 17.9 | 71.6 | 210.5 | |

| 1:2 | 3.0 | EM-1 | 480 | 120 | 1200 | 16.1 | 64.4 | 279.5 |

| 3.5 | EM-2 | 480 | 120 | 1200 | 18.8 | 75.2 | 266 | |

| 4.0 | EM-3 | 480 | 120 | 1200 | 21.5 | 85.9 | 252.6 | |

| 1:3 | 3.0 | EM-4 | 400 | 100 | 1500 | 13.4 | 53.7 | 232.9 |

| 3.5 | EM-5 | 400 | 100 | 1500 | 15.7 | 62.6 | 221.7 | |

| 4.0 | EM-6 | 400 | 100 | 1500 | 17.9 | 71.6 | 210.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, L.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, D.; Wang, L.; Wang, N. Influence of Alkaline Electrolyzed Water on the Strength, Shrinkage Behavior, and Microstructure of Alkali-Activated Fly Ash/Slag Composites. Materials 2025, 18, 5493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245493

Li L, Wu Y, Wang H, Zhu Z, Wu D, Wang L, Wang N. Influence of Alkaline Electrolyzed Water on the Strength, Shrinkage Behavior, and Microstructure of Alkali-Activated Fly Ash/Slag Composites. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245493

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Lili, Yaning Wu, Haozhe Wang, Zhen Zhu, Dingyuan Wu, Liang Wang, and Ning Wang. 2025. "Influence of Alkaline Electrolyzed Water on the Strength, Shrinkage Behavior, and Microstructure of Alkali-Activated Fly Ash/Slag Composites" Materials 18, no. 24: 5493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245493

APA StyleLi, L., Wu, Y., Wang, H., Zhu, Z., Wu, D., Wang, L., & Wang, N. (2025). Influence of Alkaline Electrolyzed Water on the Strength, Shrinkage Behavior, and Microstructure of Alkali-Activated Fly Ash/Slag Composites. Materials, 18(24), 5493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245493