Crystal-Plasticity-Based Micro-Mechanical Model for Simulating Plastic Deformation of TC4 Alloy

Abstract

1. Introduction

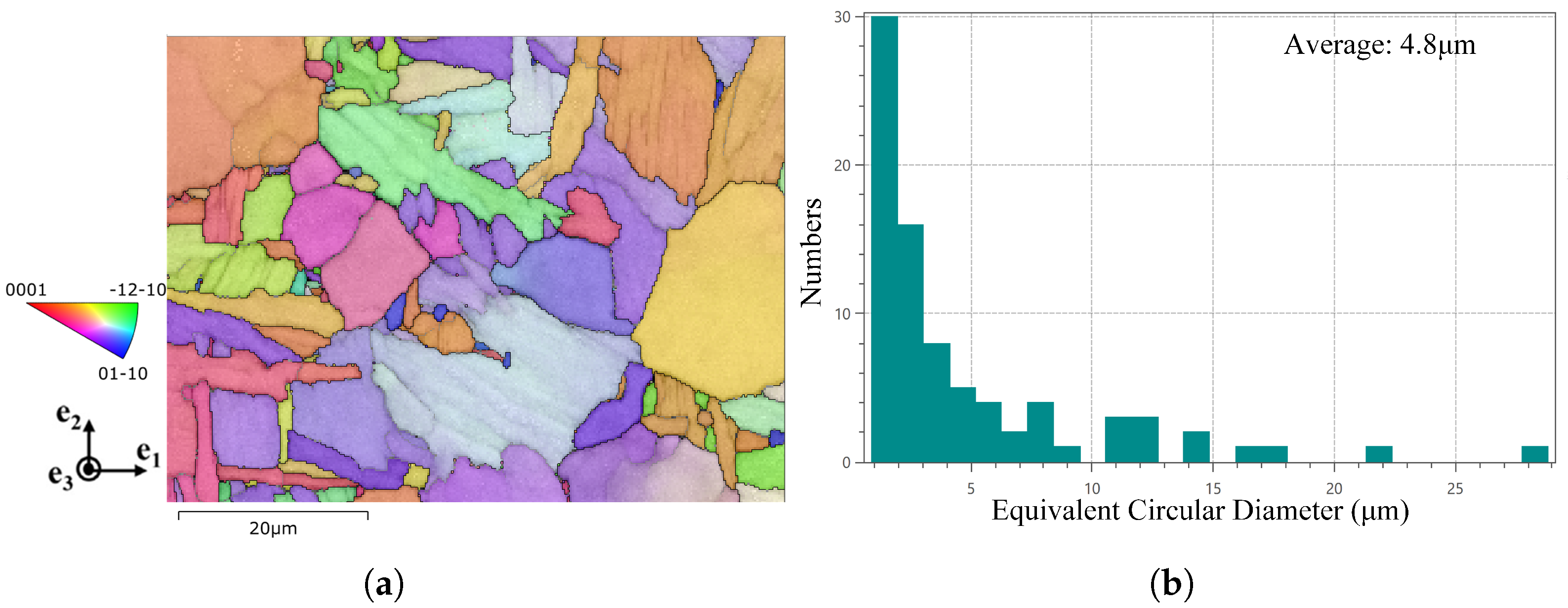

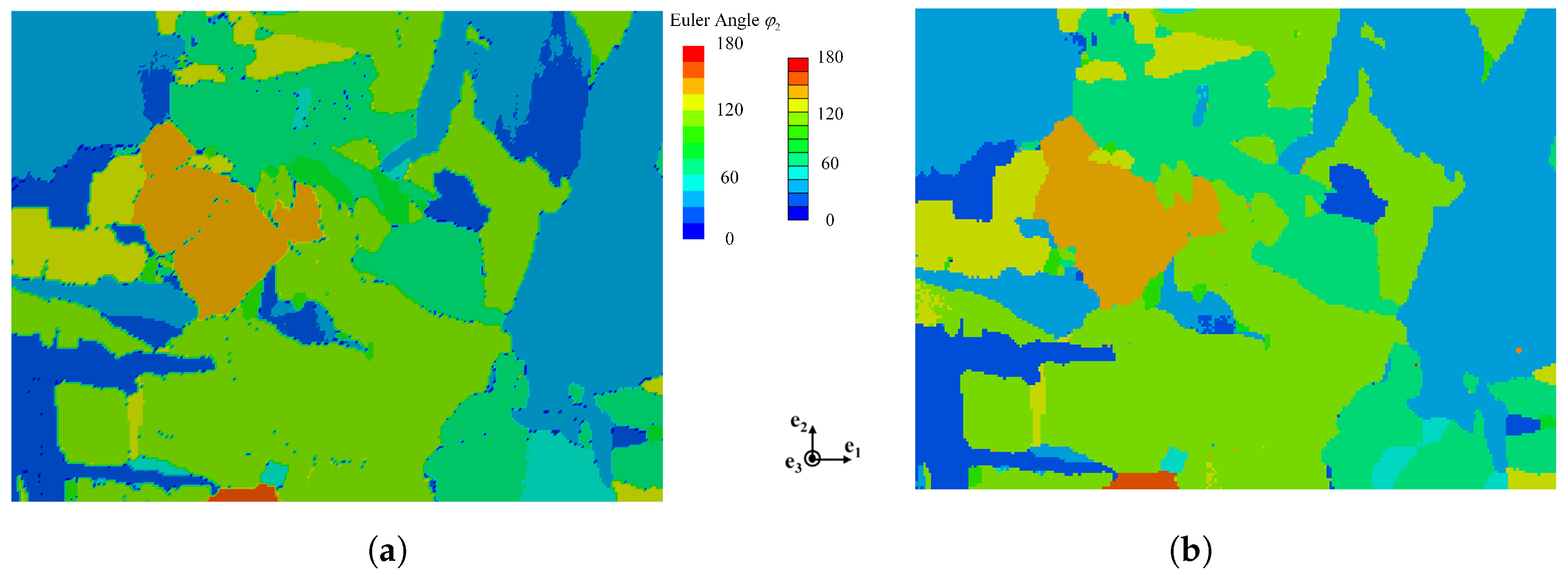

2. Experimental Procedures

3. Micromechanical Model for Polycrystals

3.1. Kinetic Formulation for a Single Crystal

3.2. Representative Volume Elements

4. Results and Discussion

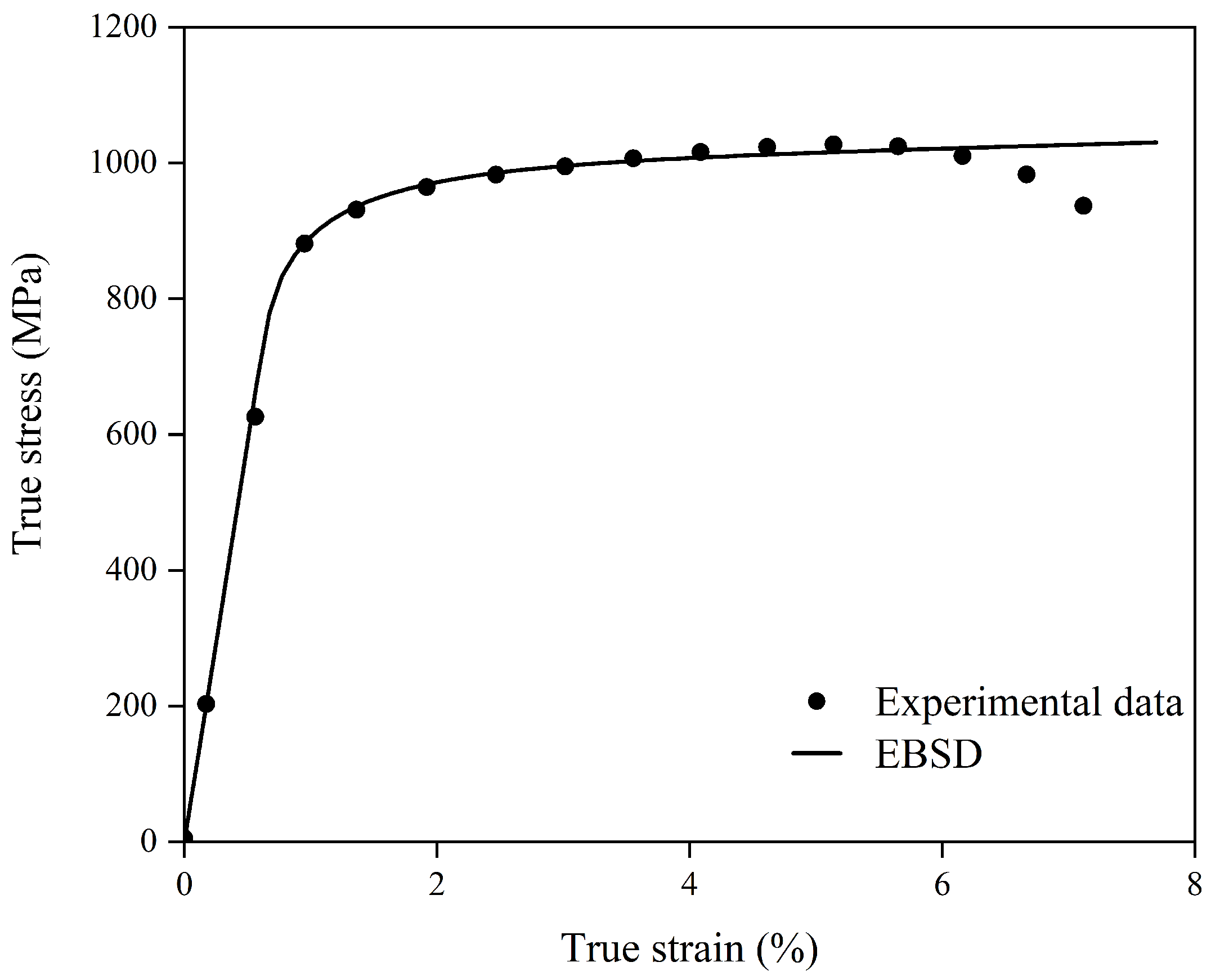

4.1. Calibrations of the Material Parameters in the Crystal Plasticity Model

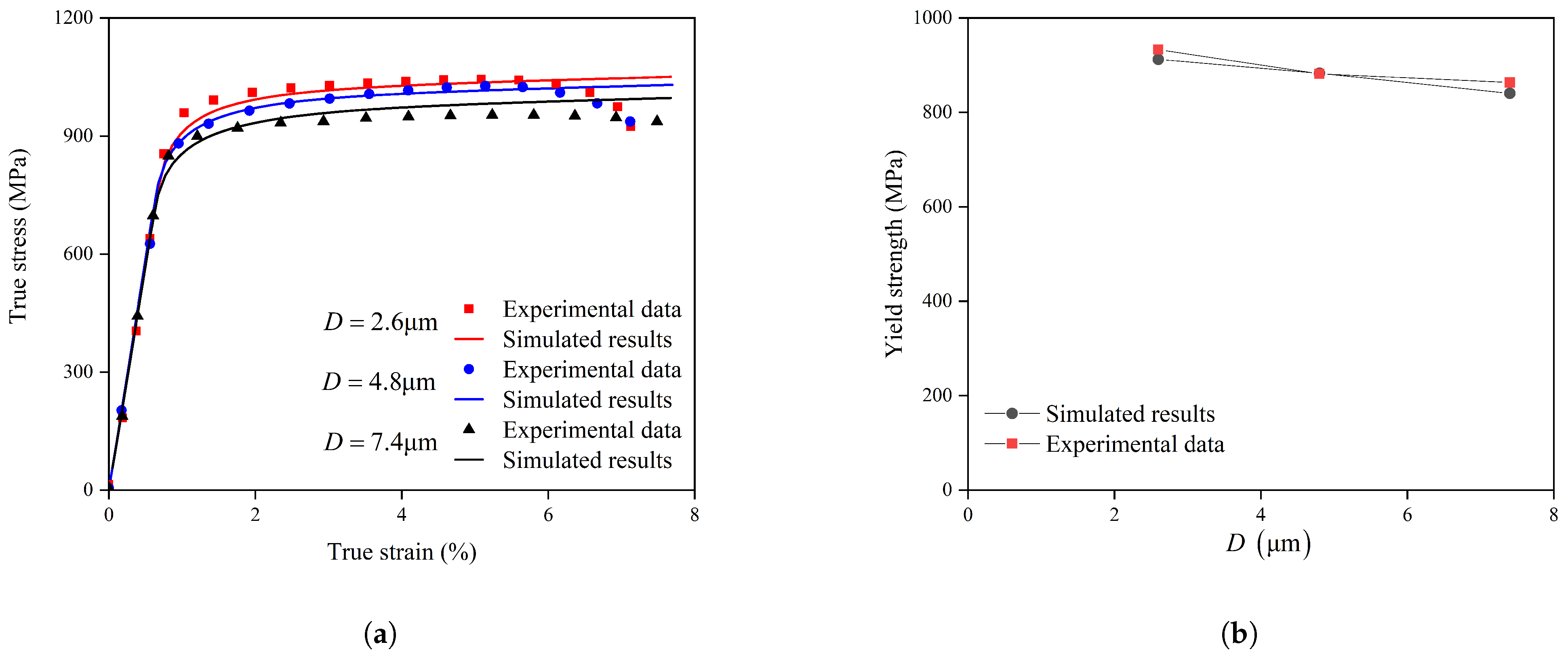

4.2. Grain-Size Model Validation

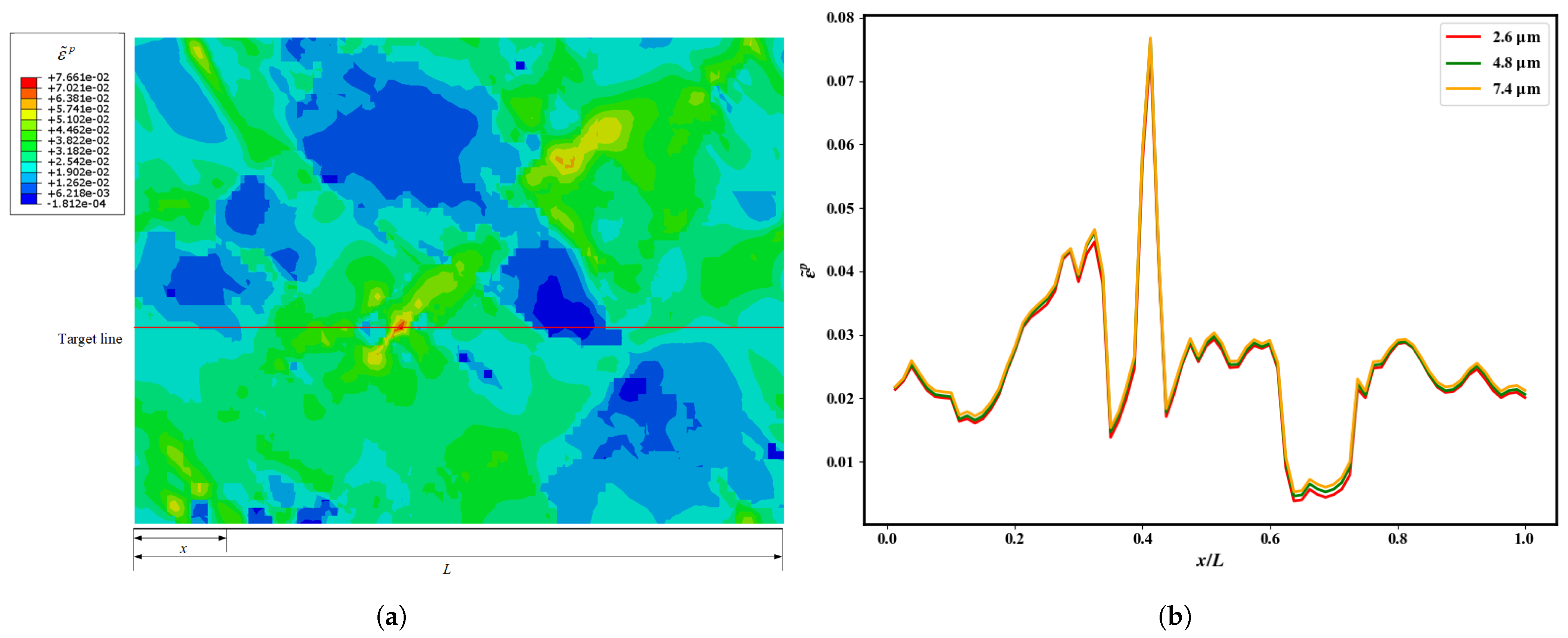

4.3. Effect of Grain Size

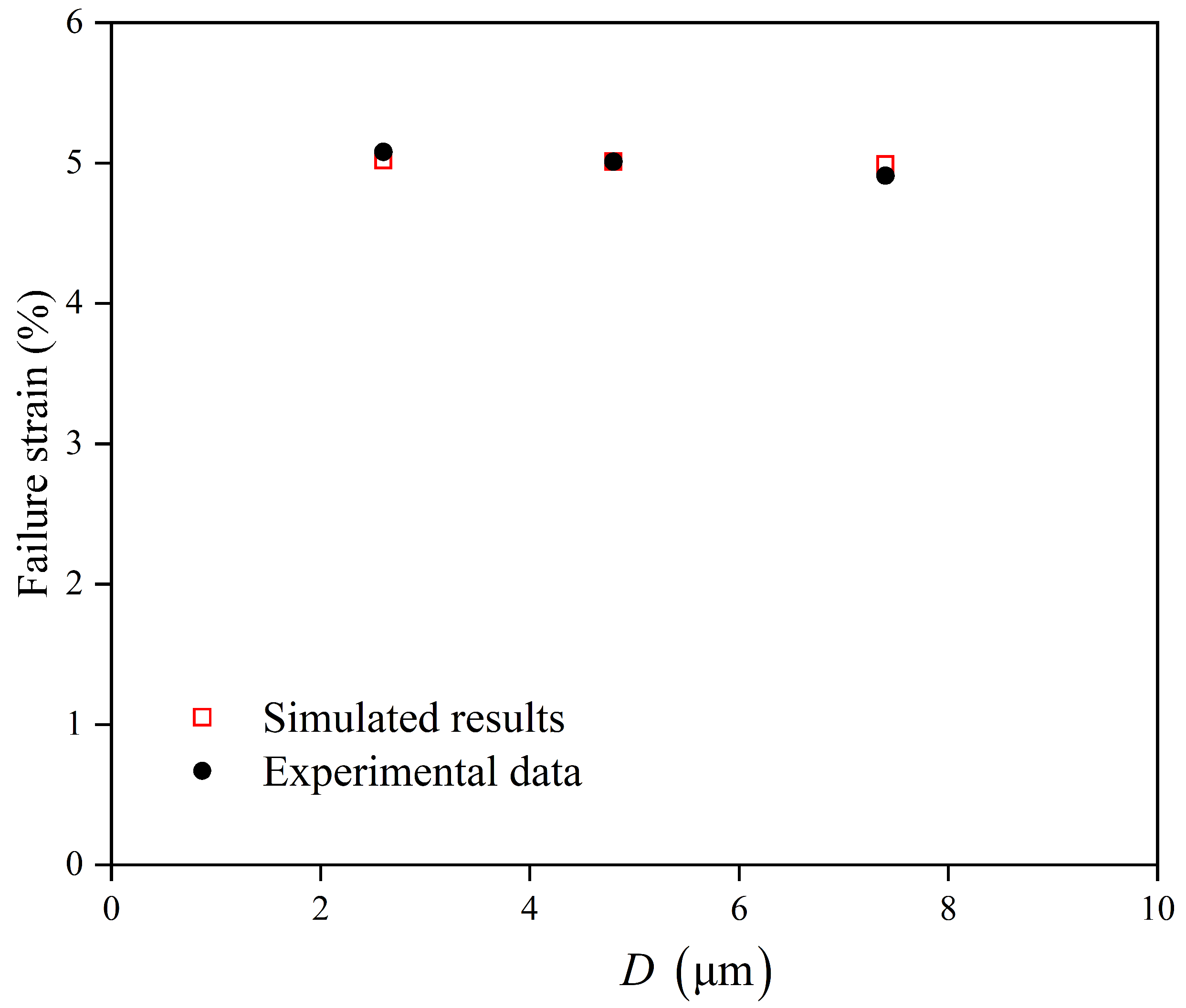

4.4. Failure Prediction

5. Summary and Conclusions

- (1)

- A thermally activated crystal plasticity model, which explicitly incorporates a Hall–Petch relationship for the initial slip resistance, was successfully developed and calibrated. The model demonstrates high fidelity in predicting the flow stress and strain-hardening behavior of TC4 alloy under uniaxial tension at room temperature.

- (2)

- The model quantitatively captures the grain-size-strengthening effect. Simulations and experiments consistently showed that a reduction in grain size from 7.4 µm to 2.6 µm leads to a significant increase in yield strength, validating the integrated Hall–Petch parameters.

- (3)

- Grain size has a profound influence on strain localization. The numerical results reveal that coarser-grained microstructures develop more intense and heterogeneous local plastic strain concentrations, which act as potential sites for damage initiation.

- (4)

- A local failure initiation criterion, defined by a critical value of accumulated equivalent plastic strain (PEEQcrit = 0.14), was established based on the experimental ultimate tensile strength. This criterion successfully predicts the macroscopic failure strain for different grain sizes.

- (5)

- The predicted failure strain decreases with an increasing grain size. This trend is associated with strain localization phenomena that lead to accelerated damage accumulation in coarser-grained microstructures.

- (6)

- It is important to note that the Hall–Petch relationship is typically valid for grain sizes ranging from approximately 1 to 30 µm in titanium alloys. The current model was calibrated and validated within a specific subset (2.6–7.4 µm) of this established range, where its predictive accuracy is high. Extrapolation to grain sizes significantly outside this validated range (particularly to ultra-fine grains < 1 µm or very coarse grains > 30 µm) may require the incorporation of additional physical mechanisms into the constitutive model.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bambach, M.; Sizova, I.; Szyndler, J.; Bennett, J.; Hyatt, G.; Cao, J.; Papke, T.; Merklein, M. On the hot deformation behavior of Ti-6Al-4V made by additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2021, 288, 116840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murr, L.E.; Esquivel, E.V.; Quinones, S.A.; Gaytan, S.M.; Lopez, M.I.; Martinez, E.Y.; Medina, F.; Hernandez, D.H.; Martinez, E.; Martinez, J.L.; et al. Microstructures mechanical properties of electron beam-rapid manufactured Ti-6Al-4V biomedical prototypes compared to wrought Ti-6Al-4V. Mater. Charact. 2009, 60, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Chen, C.; Wang, W.; Cao, T.; Shuai, S.; Xu, S.; Hu, T.; Liao, H.; Wang, J.; Ren, Z. On the role of volumetric energy density in the microstructure and mechanical properties of laser powder bed fusion Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 51, 102605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.F.; O’Dowd, N.P. On the evolution of lattice deformation in austenitic stainless steels—The role of work hardening at finite strains. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2011, 59, 2421–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, C.; Besson, J.; Forest, S.; Tanguy, B.; Latourte, F.; Bosso, E. An elastoviscoplastic model for porous single crystals at finite strains and its assessment based on unit cell simulations. Int. J. Plast. 2016, 84, 58–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somlo, K.; Poulios, K.; Funch, C.V.; Niordson, C.F. Anisotropic tensile behaviour of additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V simulated with crystal plasticity. Mech. Mater. 2021, 162, 104034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Kazim, S.M.; Prasad, K.; Chakraborty, P. Crystal plasticity modeling of a titanium alloy under thermo-mechanical fatigue. Mech. Res. Commun. 2021, 111, 103647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, M.F.; Violatos, I.; Rahimi, S. Predicting Fatigue Crack Initiation in Milled Aerospace Grade Ti-6Al-4Vparts Using CPFEM. In Proceedings of the 9th Engineering Integrity Society International Conference on Durability & Fatigue, Cambridge, UK, 19–21 June 2024; pp. 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Hu, L.; Ji, D. Investigation on Anisotropic Behavior of Additively Manufactured Ti-6Al-4V Based on Cellular Automaton CPFEM. Met. Mater. Int. 2025, 31, 2578–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roters, F.; Eisenlohr, P.; Hantcherli, L.; Tjahjanto, D.D.; Bieler, T.R.; Raabe, D. Overview of constitutive laws, kinematics, homogenization and multiscale methods in crystal plasticity finite-element modeling: Theory, experiments, applications. Acta Mater. 2010, 58, 1152–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Umezawa, O. Crystal plasticity analysis of temperature-sensitive dwell fatigue in Ti-6Al-4V titanium alloy for an aero-engine fan disc. Int. J. Fatigue 2022, 156, 106688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dunne, F.P.E. The mechanistic link between macrozones and dwell fatigue in titanium alloys. Int. J. Fatigue 2021, 142, 105971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Adande, S.; Britton, T.B.; Dunne, F.P.E. Cold dwell fatigue analyses integrating crystal-level strain rate sensitivity and microstructural heterogeneity. Int. J. Fatigue 2021, 151, 106398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roters, F. Advanced Material Models for the Crystal Plasticity Finite Element Method: Development of a General CPFEM Framework. Ph.D. Thesis, RWTH Aachen University, Aachen, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, G.I. Plastic strain in metals. J. Inst. Met. 1938, 62, 307–324. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, J.W.; Hill, R. Elastic-plastic behaviour of polycrystalline metals and composites. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1997, 319, 247–272. [Google Scholar]

- Neil, C.J.; Wollmershauser, J.A.; Clausen, B.; Tomé, C.N.; Agnew, S.R. Modeling lattice strain evolution at finite strains and experimental verification for copper and stainless steel using in situ neutron diffraction. Int. J. Plast. 2010, 26, 1772–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, P.D.; Tomé, C.N.; Huang, Y. A finite strain elastic–viscoplastic self-consistent model for polycrystalline materials. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2010, 58, 594–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshelby, J.D.; Peierls, R.E. The determination of the elastic field of an ellipsoidal inclusion, and related problems. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1957, 241, 376–396. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W.; Sun, C.; Wang, C.; Qian, L.; Li, Y.; Fu, M.W. Modelling of the intergranular fracture of TWIP steels working at high temperature by using CZM–CPFE method. Int. J. Plast. 2022, 156, 103366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Geng, S.; Qiu, Y.; Xu, B.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, P.; Hu, Y.; Li, S. In-situ EBSD-DIC simulation of microstructure evolution of aluminum alloy welds. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 284, 109741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, A.; Chakraborty, P.; Jain, R.; Sahu, V.K.; Gurao, N.P.; Bar, H.N.; Khutia, N. Influence of Scanning and Building Strategies on the Deformation Behavior of Additively Manufactured AlSi10Mg: CPFEM and Finite Element Studies. Met. Mater. Int. 2023, 29, 2978–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.Z.; Demkowicz, M.J.; Fu, E.G.; Wang, Y.Q.; Misra, A. Effect of grain boundary character on sink efficiency. Acta Mater. 2012, 60, 6341–6351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allain-Bonasso, N.; Wagner, F.; Berbenni, S.; Field, D.P. Astudy of the heterogeneity of plastic deformation in IF steel by EBSD. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 548, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.P.; Ng, T.-S.; Kuo, J.-C.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-L.; Ding, S.-X. EBSD study on crystallographic texture and microstructure development of cold-rolled FePd alloy. Mater. Charact. 2014, 93, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, S.; Anand, L. Plasticity of initially textured hexagonal polycrystals at high homologous temperatures: Application to titanium. Acta Mater. 2002, 50, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, M.; Anand, L. Elasto-viscoplastic constitutive equations for polycrystalline metals: Application to tantalum. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1998, 46, 51–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.H. Elastic-Plastic Deformation at Finite Strains. J. Appl. Mech. 1969, 36, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaro, R.J.; Rice, J.R. Strain localization in ductile single crystals. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1977, 25, 309–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busso, E.P.; McClintock, F.A. A dislocation mechanics-based crystallographic model of a B2-type intermetallic alloy. Int. J. Plast. 1996, 12, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatramani, G.; Ghosh, S.; Mills, M. A size-dependent crystal plasticity finite-element model for creep and load shedding in polycrystalline titanium alloys. Acta Mater. 2007, 55, 3971–3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Chakraborty, P. Microstructure and load sensitive fatigue crack nucleation in Ti-6242 using accelerated crystal plasticity FEM simulations. Int. J. Fatigue 2013, 48, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.-D.; Wang, L.; Zhu, B.-Y.; Jin, X.; Li, C.-F.; Busso, E.P.; Li, D.-F. Experimental and micromechanical investigation of precipitate size effects on the creep behaviour of a high chromium martensitic steel. Eur. J. Mech. A/Solids 2025, 111, 105591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.-J.; Ling, C.; Li, D.-F.; Li, C.-F.; Sun, Y.; Busso, E.P. A data-driven approach to predicting the anisotropic mechanical behaviour of voided single crystals. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2022, 159, 104700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, G. Single Crystal Elastic Constants and Caluculated Aggregate Properties: A Handbook; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Benmessaoud, F.; Cheikh, M.; Velay, V.; Vidal, V.; Matsumoto, H. Role of grain size and crystallographic texture on tensile behavior induced by sliding mechanism in Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 774, 138835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Al | V | Fe | O | C | N | Ti |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content | 5.5–6.5 | 3.5–4.5 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.20 | ≤0.08 | ≤0.05 | Bal. |

| Slip Systems | Slip Plane | Slip Direction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basal |  | ||

| Prismatic |  | ||

| Pyramidal |  | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, H.; Li, W.; Qian, Z.; Mi, D.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wu, C.; Li, K.; Tang, T.; Li, D. Crystal-Plasticity-Based Micro-Mechanical Model for Simulating Plastic Deformation of TC4 Alloy. Materials 2025, 18, 5486. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245486

Chen H, Li W, Qian Z, Mi D, Wu Y, Zhang S, Wu C, Li K, Tang T, Li D. Crystal-Plasticity-Based Micro-Mechanical Model for Simulating Plastic Deformation of TC4 Alloy. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5486. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245486

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Huanhuan, Wei Li, Zhengming Qian, Dong Mi, Yangyang Wu, Siqi Zhang, Can Wu, Keke Li, Tiezheng Tang, and Dongfeng Li. 2025. "Crystal-Plasticity-Based Micro-Mechanical Model for Simulating Plastic Deformation of TC4 Alloy" Materials 18, no. 24: 5486. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245486

APA StyleChen, H., Li, W., Qian, Z., Mi, D., Wu, Y., Zhang, S., Wu, C., Li, K., Tang, T., & Li, D. (2025). Crystal-Plasticity-Based Micro-Mechanical Model for Simulating Plastic Deformation of TC4 Alloy. Materials, 18(24), 5486. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245486