C15-Structured Zr-Ti-Fe-Ni-V Alloys for High-Pressure Hydrogen Compression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Alloy Preparation

2.2. Structural Characterization

2.3. Hydrogen Storage Measurement

3. Results and Discussion

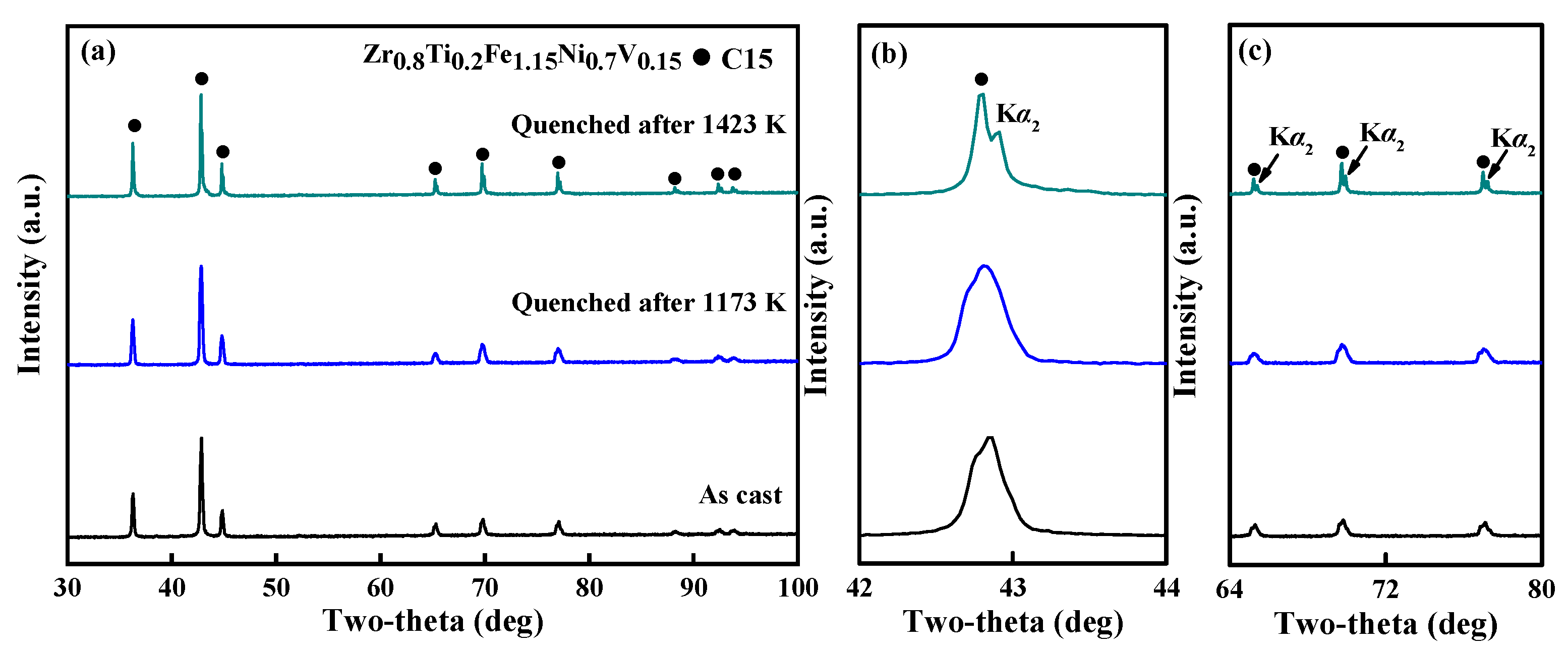

3.1. Microstructures of Alloys

| Alloys | e/a | RA/RB | Phase | a (Å) | c (Å) | V (Å3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 1.58 | 1.240 | C15 | 6.9994 | 342.91 | |

| #2 | 1.67 | 1.234 | C15 | 6.9917 | 341.78 | |

| #3 | 1.75 | 1.239 | C15 | 7.0053 | 343.78 | |

| #4 | 1.75 | 1.225 | C14 | 4.9453 | 8.0605 | 170.72 |

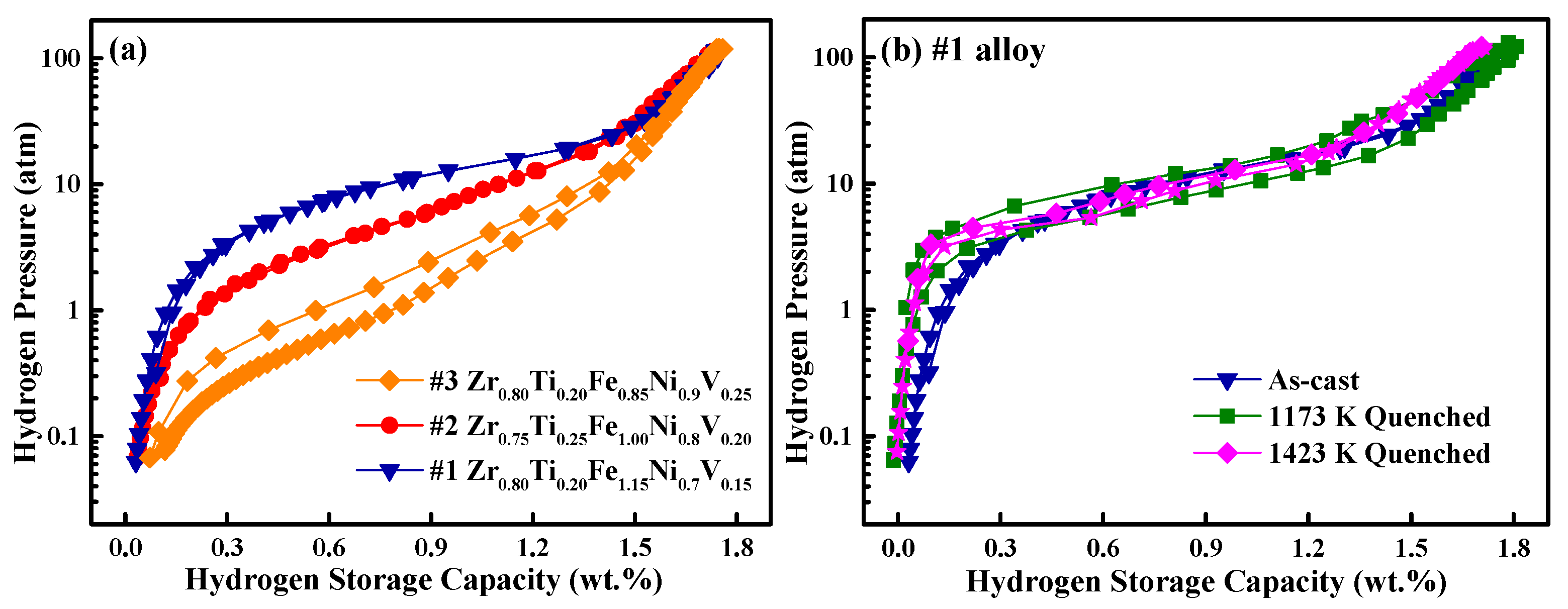

3.2. Hydrogen Storage Properties

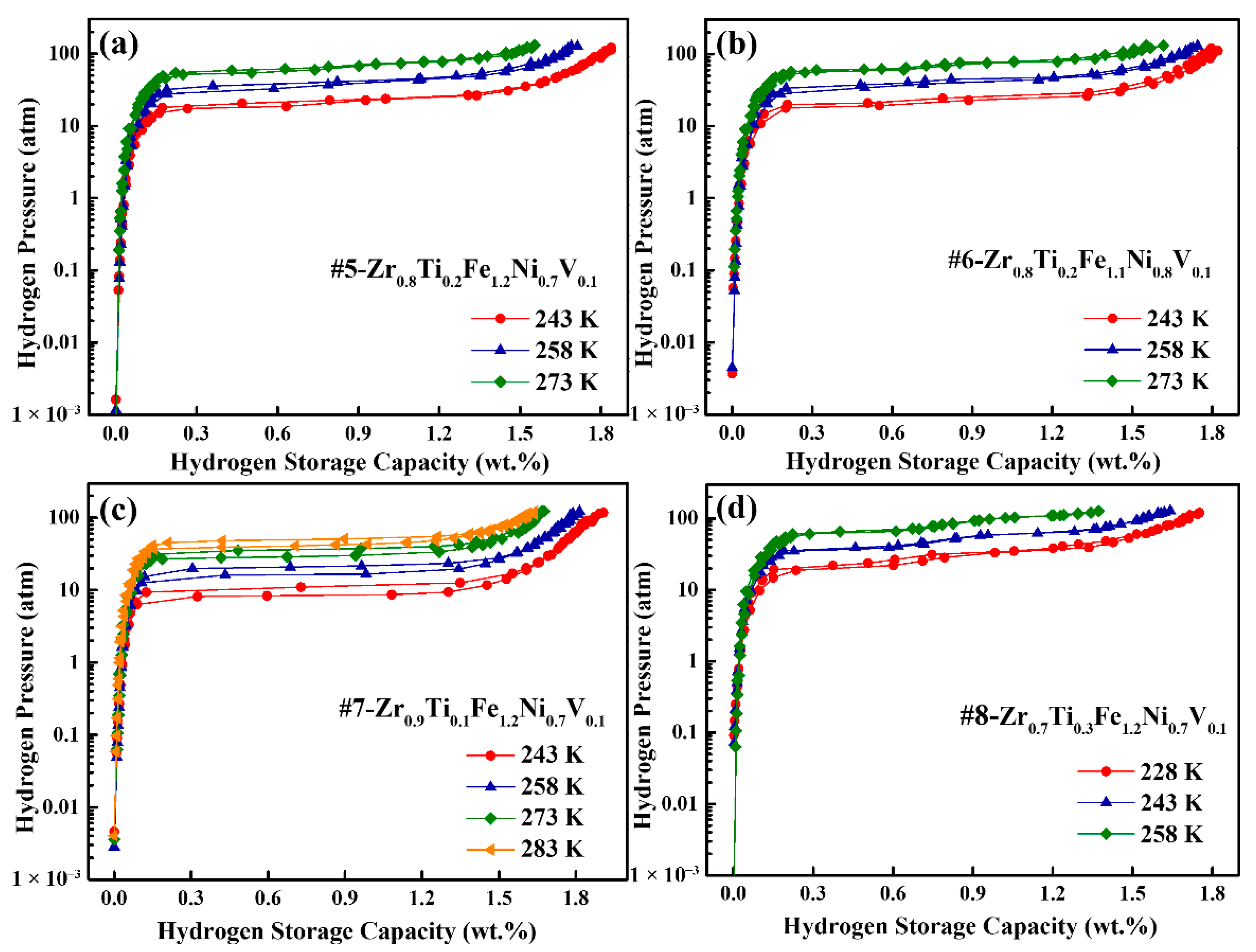

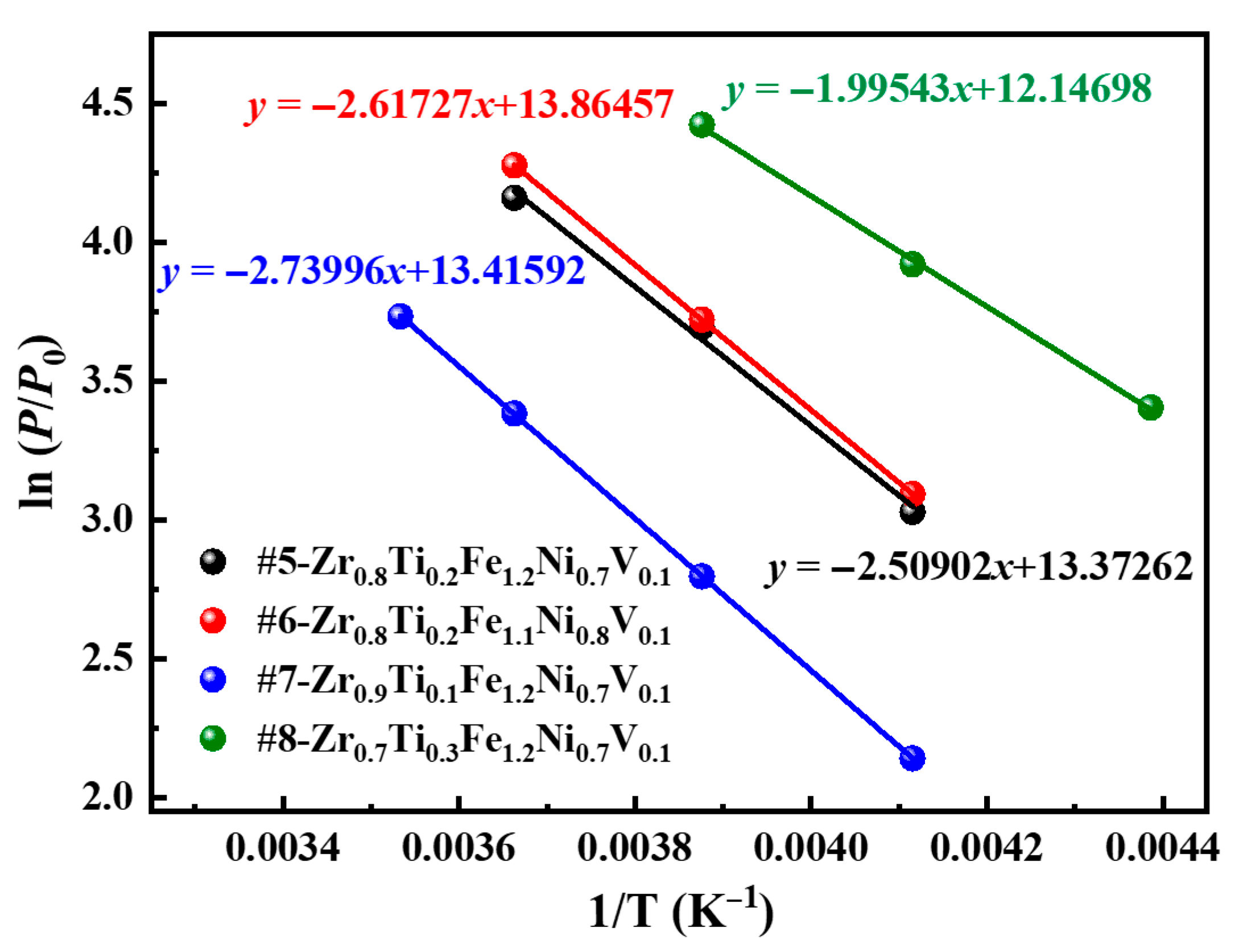

3.3. Optimization of Alloy’s Composition and Hydrogen Storage Performance

3.4. Hydrogen Compression Performance

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, X.W.; Shi, L.X.; Ma, C.; Zhang, W.T.; Xia, C.Q.; Yang, T. Effects of Ti Substitution by Zr on Microstructure and Hydrogen Storage Properties of Laves Phase AB2-Type Alloy. Materials 2025, 18, 3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asano, K.; Bannenberg, L.J.; Schreuders, H.; Hashimoto, H.; Isobe, S.; Nakahira, Y.; Machida, A.; Kim, H.; Sakaki, K. Distortion and Destabilization of Mg Hydride Facing High Entropy Alloy Matrix. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2024, 7, 11644–11651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebon, L.; Maynadier, A.; Gaillard, Y.; Chapelle, D. Multiscale Elastic Modulus Characterization of Ti0.5Fe0.45Mn0.05, an Iron–Titanium–Manganese Alloy Dedicated to Hydrogen Storage. Materials 2024, 17, 6100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, L.Z.; Dong, H.W.; Peng, C.H.; Sun, L.X.; Zhu, M. A new type of Mg-based metal hydride with promising hydrogen storage properties. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2007, 32, 3929–3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.P.; Jia, Y.X.; Xiao, X.Z.; Cao, Z.M.; Zhou, P.P.; Zhan, L.J.; Piao, M.Y.; Chu, F.; Yuan, S.C.; Chen, L.X. Development of Ti-Zr-Mn-Cr-(V-Fe) based alloys for hydrogen feeding system in hydrogen metallurgy application. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 86, 1376–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.Y.; Zhou, P.P.; Chen, S.L.; Shen, S.Y.; Liu, X.Y.; Xiao, X.Z.; Li, Z.N.; Ouyang, L.Z. Solid-state hydrogen storage alloys for production-storage and transportation-application coupling at ambient temperature: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2026, 167, 101089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdanghi, G.; Maranzana, G.; Celzard, A.; Fierro, V. Review of the current technologies and performances of hydrogen compression for stationary and automotive applications. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2019, 102, 150–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumar, P.; Patel, K.S.; Sachan, P.; Singhal, N. Computational study on metal hydride based three-stage hydrogen compressor. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 3797–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.K.; Kumar, E.A. Metal hydrides for energy applications-classification, PCI characterisation and simulation. Int. J. Energy Res. 2017, 41, 901–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lototsky, M.V.; Yartys, V.A.; Marinin, V.S.; Lototsky, N.M. Modelling of phase equilibria in metal-hydrogen systems. J. Alloys Compd. 2003, 356–357, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumar; Maiya, P.M.; Murthy, S.S. Parametric studies on a metal hydride based single hydrogen compressor. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2002, 27, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lototskyy, M.V.; Yartys, V.A.; Pollet, B.G.; Bowman, R.C., Jr. Metal hydride hydrogen compressors: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 5818–5851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvis, E.A.R.; Leardini, F.; Ares, J.R.; Cueva, F.; Fernandez, J.F. Experimental behavior of a three-stage metal hydride hydrogen compressor. J. Phys.-Energy 2020, 2, 034006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashbabu, D.; Kumar, E.A.; Jain, I.P. Thermodynamic analysis of a metal hydride hydrogen compressor with aluminum substituted LaNi5 hydrides. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 37886–37897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurencelle, F.; Dehouche, Z.; Morin, F.; Goyette, J. Experimental study on a metal hydride based hydrogen compressor. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 475, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Bei, Y.Y.; Song, X.C.; Fang, G.H.; Li, S.Q.; Chen, C.P.; Wang, Q.D. Investigation on high-pressure metal hydride hydrogen compressors. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2007, 32, 4011–4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, M.; Wang, Q.D. Rare earth-nickel alloy for hydrogen compression. J. Alloys Compd. 1993, 201, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Chen, R.G.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.P.P.; Wang, Q.D. Hydrogen storage alloys for high-pressure suprapure hydrogen compressor. J. Alloys Compd. 2006, 420, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhanen, J.P.; Hagström, M.T.; Lund, P.D. Combined hydrogen compressing and heat transforming through metal hydrides. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1999, 24, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, K.; Banerjee, T.; Witman, M.D.; Allendorf, M.D.; Stavila, V.; Singh, P. Design of lightweight BCC multi-principal element alloys with enhanced hydrogen storage using a machine learning-driven genetic algorithm. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 41274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, L.; Charbonnier, V.; Fadonougbo, J.; Clulow, R.; Lei, L.; Ling, S.; Grant, D.; Dornheim, M.; Banerjee, T.; Breunig, H.; et al. Efficiently predicting pressure-composition-temperature diagrams to discover low-stability metal hydrides. ChemRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.S.; Wang, H.; Jiang, W.; Liu, J.W.; Ouyang, L.Z.; Zhu, M. Comparative study of Ga and Al alloying with ZrFe2 for high-pressure hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 27, 13409–13417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Kumar, A.; Pillai, C.G.S. Improvement on the hydrogen storage properties of ZrFe2 Laves phase alloy by vanadium substitution. Intermetallics 2014, 51, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.B.; Wang, X.F.; Hu, R.; Li, J.S.; Yang, X.W.; Xue, X.Y.; Fu, H.Z. Hydrogen absorption properties of Zr(V1−xFex)2 intermetallic compounds. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 2328–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koultoukis, E.D.; Makridis, S.S.; Pavlidou, E.; Rango, P.D.; Stubos, A.K. Investigation of ZrFe2-type materials for metal hydride hydrogen compressor systems by substituting Fe with Cr or V. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 21380–21385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Jain, R.K.; Agarwal, S.; Sharma, R.K.; Kulshrestha, S.K.; Jain, I.P. Structural and Mossbauer spectroscopic study of cubic phase ZrFe2−xMnx hydrogen storage alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2008, 454, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaina, A.; Jaina, R.K.; Agarwala, S.; Ganesanb, V.; Lallab, N.P.; Phaseb, D.M.; Jaina, I.P. Synthesis, characterization and hydrogenation of ZrFe2−xNix (x = 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8) alloys. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2007, 32, 3965–3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivov, R.B.; Zotov, T.A.; Verbetsky, V.N.; Filimonov, D.S.; Pokholok, K.V. Synthesis, properties and Mössbauer study of ZrFe2−xNix hydrides (x = 0.2–0.8). J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boultif, A.; Louer, D. Powder pattern indexing with the dichotomy method. J. Appl. Cryst. 2004, 37, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, F.; Palm, M.; Sauthoff, G. Structure and stability of Laves phases. Part I. Critical assessment of factors controlling Laves phase stability. Intermetallics 2004, 12, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.S.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.W.; Ouyang, L.Z.; Zhu, M. Tuning hydrogen storage thermodynamic properties of ZrFe2 by partial substitution with rare earth element Y. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 18445–18452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.L.; Li, Z.M.; Zhou, C.; Wang, H.; Ouyang, L.Z.; Yuan, S.R.; Zhu, Y.J.Z.A.N.M. Achieving the dehydriding reversibility and elevating the equilibrium pressure of YFe2 alloy by partial Y substitution with Zr. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 14541–14549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.S.; Zhou, C.; Ouyang, L.Z.; Liu, J.W.; Zhu, M.; Sun, T.; Wang, H. High-pressure hydrogen storage performances of ZrFe2 based alloys with Mn, Ti, and V addition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 9836–9844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotov, T.A.; Sivov, R.B.; Movlaev, E.A.; Mitrokhin, S.V.; Verbetsky, V.N. IMC hydrides with high hydrogen dissociation pressure. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 5, S839–S843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, R. Hysteresis in metal–hydrogen systems. J. Alloys Compd. 1997, 253–254, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilov, A.L.; Efremenko, N.E. Effect of sloping pressure “plateau” in two-phase regions of hydride systems. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A+ 1986, 12, 3024–3028. [Google Scholar]

- Young, K.; Ouchi, T.; Reichman, B.; Koch, J.; Fetcenko, M.A. Improvement in the low-temperature performance of AB5 metal hydride alloys by Fe-addition. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 7611–7617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, T.B.; Park, C.N.; Oates, W.A. Hysteresis in solid state reactions. Prog. Solid State Chem. 1995, 23, 291–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.; Northwood, D.O. Hysteresis in metal-hydrogen systems: A critical review of the experimental observations and theoretical models. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1988, 13, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, T.; Ji, K.; Xia, W.Y.; Ouyang, G.Y.; Rose, T.D.; Hlova, I.Z.; Ueland, B.; Johnson, D.D.; Wang, C.Z.; Balasubramanian, G.; et al. Machine-learning and first-principles investigation of lightweight medium-entropy alloys for hydrogen-storage applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 154, 149916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.D.; Zhu, S.; Zhao, X.; Cheng, H.H.; Yan, K.; Liu, J.J. Effects of Ce/Y on the cycle stability and anti-plateau splitting of La5−xCexNi4Co (x = 0.4, 0.5) and La5−yYyNi4Co (y = 0.1, 0.2) hydrogen storage alloys. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2019, 236, 121725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.Y.; Li, Q.; Sun, J.Y.; Chen, K.; Jiang, W.B.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.W.; Ouyang, L.Z.; Zhu, M. Ti-Cr-Mn-Fe-based alloys optimized by orthogonal experiment for 85 MPa hydrogen compression materials. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 891, 161791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, X.H.; Dong, Z.H.; Xu, L.; Chen, C.P. A study on 70 MPa metal hydride hydrogen compressor. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 502, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yartys, V.A.; Lototskyy, M.V.; Tolj, I.; von Colbe, J.B.; Denys, R.V.; Davids, M.W.; Nyamsi, S.N.; Swanepoel, D.; Berezovets, V.V.; Zavaliy, I.Y.; et al. HYDRIDE4MOBILITY: An EU project on hydrogen powered forklift using metal hydrides for hydrogen storage and H2 compression. J. Energy Storage 2025, 109, 115192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotov, T.; Movlaev, E.; Mitrokhin, S.; Verbetsky, V. Interaction in (Ti,Sc)Fe2-H2 and (Zr,Sc)Fe2-H2 systems. J. Alloys Compd. 2008, 459, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Tu, Y.; Tu, H.; Chen, L. Microstructures and hydrogen storage properties of ZrFe2.05−xVx (x = 0.05–0.20) alloys with high dissociation pressures for hybrid hydrogen storage vessel application. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 627, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereznitsky, M.; Jacob, I.; Bloch, J.; Mintz, M.H. Thermodynamic and structural aspects of hydrogen absorption in the Zr(AlxFe1−x)2 system. J. Alloys Compd. 2003, 351, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wang, H.; Ouyang, L.Z.; Liu, J.W.; Zhu, M. Achieving high equilibrium pressure and low hysteresis of Zr-Fe based hydrogen storage alloy by Cr/V substitution. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 806, 1436–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivov, R.B.; Zotov, T.A.; Verbetsky, V.N. Interaction of ZrFe2 doped with Ti and Al with hydrogen. Inorg. Mater. 2010, 46, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Ouyang, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Sun, L.; Felderhoff, M.; Zhu, M. Development of ZrFeV alloys for hybrid hydrogen storage system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 11242–11253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Alloys | Cm (wt.%) | Cs (wt.%) | Pa (atm) | Pd (atm) | Hf | Sf (Pd) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 alloy | 1.78 | 0.29 | 10.01 | 9.84 | 0.02 | 2.18 |

| #2 alloy | 1.74 | 0.25 | 6.06 | 5.99 | 0.01 | 2.33 |

| #3 alloy | 1.74 | 0.18 | 2.25 | 1.33 | 0.53 | 3.07 |

| #1-1173 K-quenched | 1.81 | 0.07 | 10.95 | 6.94 | 0.23 | 1.35 |

| #1-1423 K-quenched | 1.71 | 0.09 | 9.26 | 8.21 | 0.12 | 1.59 |

| Alloys | V (Å3) | T (K) | Cm (wt.%) | Pa (atm) | Pd (atm) | Hf | Sf | ΔHd (kJ/mol) | ΔSd (J/mol K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #5 | 341.92 | 243 | 1.84 | 23.20 | 20.64 | 0.12 | 0.41 | 20.86 | 111.18 |

| 258 | 1.71 | 42.66 | 40.18 | 0.06 | 0.48 | ±1.428 | ±5.553 | ||

| 273 | 1.55 | 69.18 | 64.01 | 0.08 | 0.50 | ||||

| #6 | 341.22 | 243 | 1.82 | 26.71 | 22.03 | 0.19 | 0.35 | 21.76 | 115.27 |

| 258 | 1.74 | 45.96 | 41.29 | 0.11 | 0.41 | ±0.043 | ±0.167 | ||

| 273 | 1.62 | 76.19 | 71.95 | 0.06 | 0.47 | ||||

| #7 | 345.55 | 243 | 1.90 | 11.82 | 8.50 | 0.33 | 0.19 | 22.78 | 111.54 |

| 258 | 1.81 | 21.22 | 16.38 | 0.26 | 0.19 | ±0.046 | ±0.176 | ||

| 273 | 1.67 | 36.37 | 29.44 | 0.21 | 0.06 | ||||

| #8 | 338.23 | 228 | 1.75 | 33.25 | 30.07 | 0.10 | 0.66 | 16.59 | 100.99 |

| 243 | 1.64 | 51.04 | 50.41 | 0.01 | 0.49 | ±0.452 | ±1.868 | ||

| 258 | 1.37 | 85.35 | 83.27 | 0.02 | 0.63 |

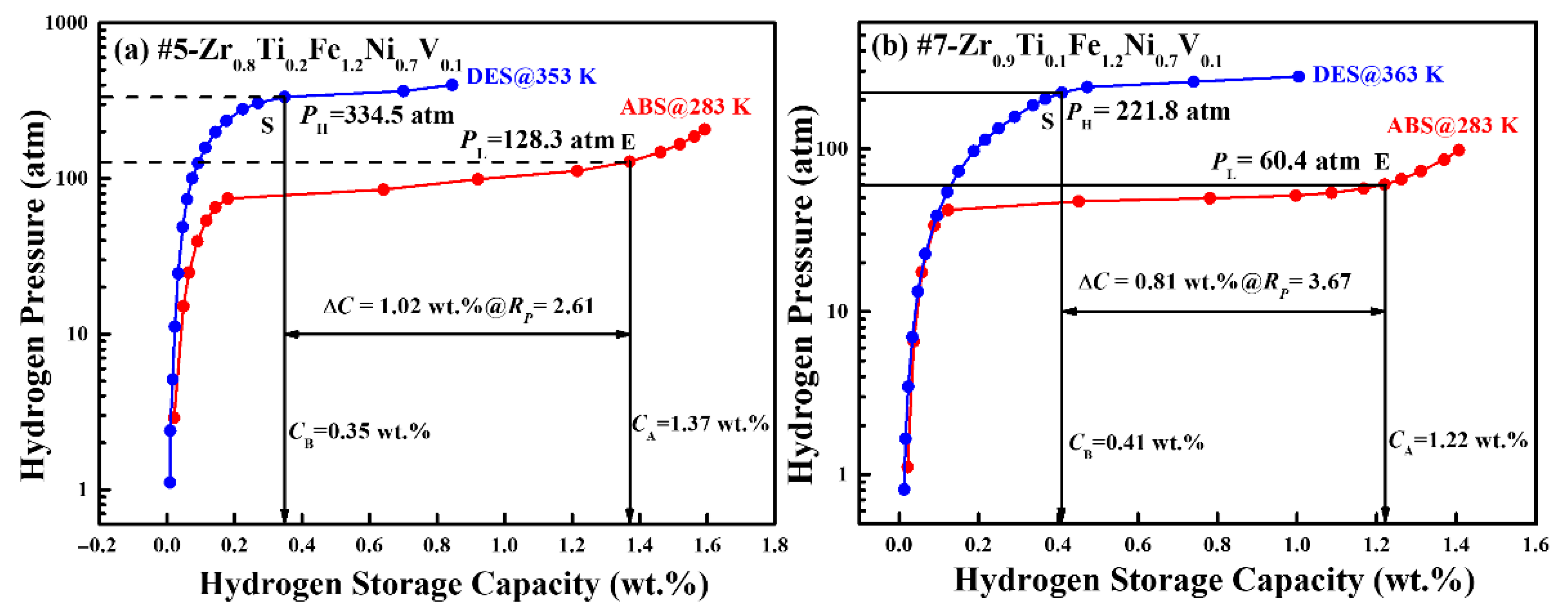

| Alloys | Temperature (K) | PL (atm) | PH (atm) | Rp | Cc (wt.%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #5-Zr0.8Ti0.2Fe1.2Ni0.7V0.1 | 283/353 | 128.3 | 334.5 | 2.61 | 1.02 | This work |

| #7-Zr0.9Ti0.1Fe1.2Ni0.7V0.1 | 283/363 | 60.4 | 221.8 | 3.67 | 0.81 | This work |

| Ti1.08Cr1.3Mn0.2Fe0.5 | 298/363 | 237.4 | 535.2 | 2.25 | 0.66 | [42] |

| Ti0.8Zr0.2Cr0.95Fe0.95V0.1 | 298/423 | 385 | 745 | 1.94 | [43] | |

| Ti0.86Mo0.14Cr1.9 | 293/363 | 830.9 | 1759 | 2.12 | [44] | |

| ZrFe1.8Ni0.2 | 293/363 | 461 | 922 | 2.00 | [44] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, J.; Qin, C.; Wang, H. C15-Structured Zr-Ti-Fe-Ni-V Alloys for High-Pressure Hydrogen Compression. Materials 2025, 18, 5482. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245482

Xu J, Qin C, Wang H. C15-Structured Zr-Ti-Fe-Ni-V Alloys for High-Pressure Hydrogen Compression. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5482. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245482

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Jie, Changsheng Qin, and Hui Wang. 2025. "C15-Structured Zr-Ti-Fe-Ni-V Alloys for High-Pressure Hydrogen Compression" Materials 18, no. 24: 5482. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245482

APA StyleXu, J., Qin, C., & Wang, H. (2025). C15-Structured Zr-Ti-Fe-Ni-V Alloys for High-Pressure Hydrogen Compression. Materials, 18(24), 5482. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245482