1. Introduction

Aramid fabrics are widely recognized as common materials for soft bulletproof applications. Regarding fabric structure, Islam et al. [

1] highlighted that satin/sateen fabrics surpass plain fabrics in performance due to their longer floating yarns, which facilitate faster stress propagation across the fabric. Further research by Chu et al. [

2] compared the ballistic performance of sateen, plain, and unidirectional (UD) fabrics. Their findings revealed that sateen fabric exhibits superior ballistic performance, particularly when the number of layers and the CIF are increased. This is attributed to its greater interpenetration compared to UD fabric and the increased number of straight joints compared to plain fabric, both of which contribute to energy absorption and dispersion. In addition to its ballistic advantages, satin/sateen fabric is also superior in terms of comfort. Limeneh et al. [

3] noted that satin/sateen structures offer higher air permeability, better water absorption, and lower thermal resistance and stiffness compared to twill and plain structures. These properties make satin/sateen fabrics particularly suitable for flexible body armor, meeting the dual requirements of softness and comfort. Thus, satin/sateen aramid fabrics represent an optimal choice for applications demanding both high ballistic protection and wearer comfort.

The CIF is one of the critical factors influencing ballistic performance [

4]. Wang et al. [

5] investigated the effect of the CIF on fabric ballistic performance using finite element (FE) simulation. Their findings indicated that within a certain range, increasing the inter-yarn friction coefficient enhanced the fabric’s bulletproof performance. Building on these results, researchers have explored various methods to increase the inter-yarn friction in fabrics. Shear thickening fluid (STF) has emerged as an effective energy-absorbing material solution due to its unique properties, while nanomaterials have gained significant attention in this field owing to their lightweight characteristics [

6]. Research demonstrates that STF treatment can remarkably enhance the frictional performance of Kevlar fabrics, with yarn pull-out force increasing by 213.2% compared to untreated samples [

7]. Notably, aramid fabrics treated with B

4C-modified STF exhibit superior ballistic protection performance, showing an increase in ballistic limit velocity from 114 m/s to 179 m/s (a 57% improvement). Further structural optimization reveals that a multi-layer configuration combining one layer of STF-treated fabric with five layers of untreated fabric achieves optimal energy absorption efficiency [

8]. In addition to STF treatment, other surface modification techniques have also proven effective in enhancing fabric performance. For instance, the glancing angle deposition technique has been employed to deposit aligned silver nanorods (AgNRs) onto aramid fabrics, significantly enhancing inter-yarn friction and improving ballistic performance. This nano-coating maintains the fabric’s flexibility and weight while increasing the inter-yarn friction force by 130% [

9]. Similarly, LaBarre et al. [

10] demonstrated that incorporating multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWNTs) into aramid fibers increases the inter-yarn force by 230%. Their study showed that Kevlar

® treated with MWNTs exhibited a 15% increase in yarn modulus, a 30% increase in the CKF, a 30% increase in yarn pull-out force, and an increase of approximately 50% in ballistic limit. Shao et al. [

11] further explored the friction properties of aramid woven fabrics modified with carboxylated cellulose nanofibers (CNF-C). Their experiments revealed that CNF-C modification significantly improved yarn pull-out force and fiber surface roughness. The optimal conditions—immersion for 0.5 h and a CNF-C concentration of 1 wt%—resulted in a pull-out force of 13.3 N, representing a 133.3% increase compared to untreated fabrics. These advancements highlight the potential of nanomaterials in enhancing the ballistic performance of aramid fabrics while keeping them lightweight and flexible.

Among the various nanomaterials available for surface modification, ZnO nanomaterials have garnered significant attention due to their ease of processing, low toxicity, cost-effectiveness, and compatibility with industrial-scale production. Xu et al. [

12] investigated the ballistic properties of ZnO-modified aramid fabrics and found that the ballistic limit velocity of ZnO-treated two-layer and three-layer fabrics increased by 16% and 35.6%, respectively, while their surface density decreased by 45.9% and 27.9%. The growth of ZnO nanowires on aramid fibers significantly enhances inter-yarn friction, resulting in peak yarn pull-out force and energy absorption that are 10.85 times and 22.70 times greater than untreated fabrics, respectively [

13]. Malakooti et al. [

14] demonstrated that ZnO-coated fabrics can effectively modulate inter-yarn friction and impact resistance, with the maximum impact force of a single aramid fabric improving by approximately 66% within a specific impact velocity range.

Further advancements have been made by Majumdar et al. [

15], who developed ZnO nanostructures on Kevlar

® fabrics, achieving an 85% increase in tensile strength for Kevlar

® fibers and a 24% increase for their composites. Additionally, the impact energy absorption of Kevlar

® fibers and their composites have been improved by 60% and 35%, respectively. Hazarika et al. [

16] grafted ZnO nanorods onto woven Kevlar

® fabrics, enhancing the interfacial strength of Kevlar

®/polyester resin composites and achieving up to a 60% increase in impact energy absorption. Steinke et al. [

17] explored the effects of zinc oxide nanowires (ZnO NWs) grown on UHMWPE woven fabrics, reporting a 663.5% increase in friction and an 822.9% increase in pull-out energy. These modifications led to a 59.13% increase in the V

50 ballistic limit and a 227% increase in energy absorption compared to untreated fabrics. Arora et al. [

18] analyzed the impact response of ZnO nanorod-grafted UHMWPE woven fabrics, noting significant increases in inter-yarn friction (44% to 329%) and yarn pull-out force. Castellanos et al. [

19] studied the low-velocity impact performance of ZnO nanowire-modified fabrics, observing strong resistance to damage during impact tests. Importantly, the flexibility of Kevlar

® fabric remained unchanged after ZnO nanowire coating, while the yarn pull-out force and energy under 100 N tension were increased by 266% and 293%, respectively [

18]. These findings underscore the potential of ZnO nanomaterials to enhance the mechanical and ballistic properties of fabrics while maintaining their flexibility and lightweight characteristics, making them a promising candidate for advanced protective materials.

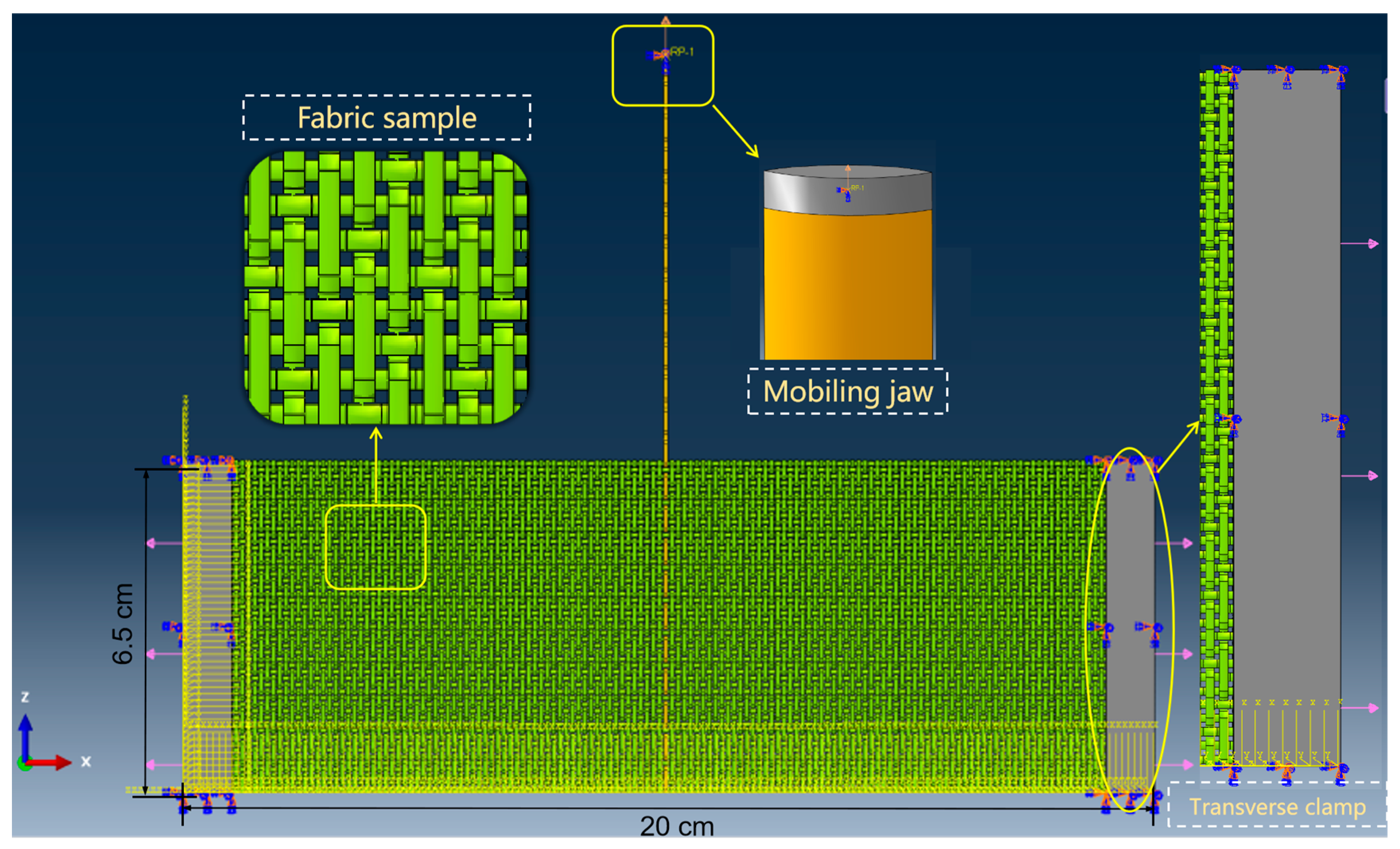

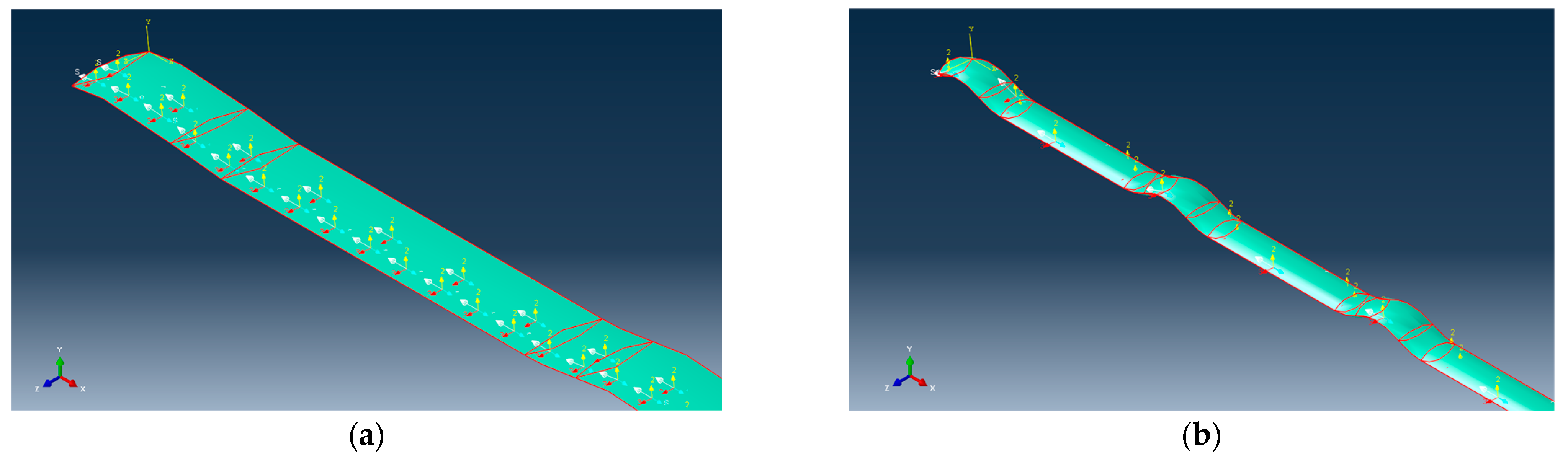

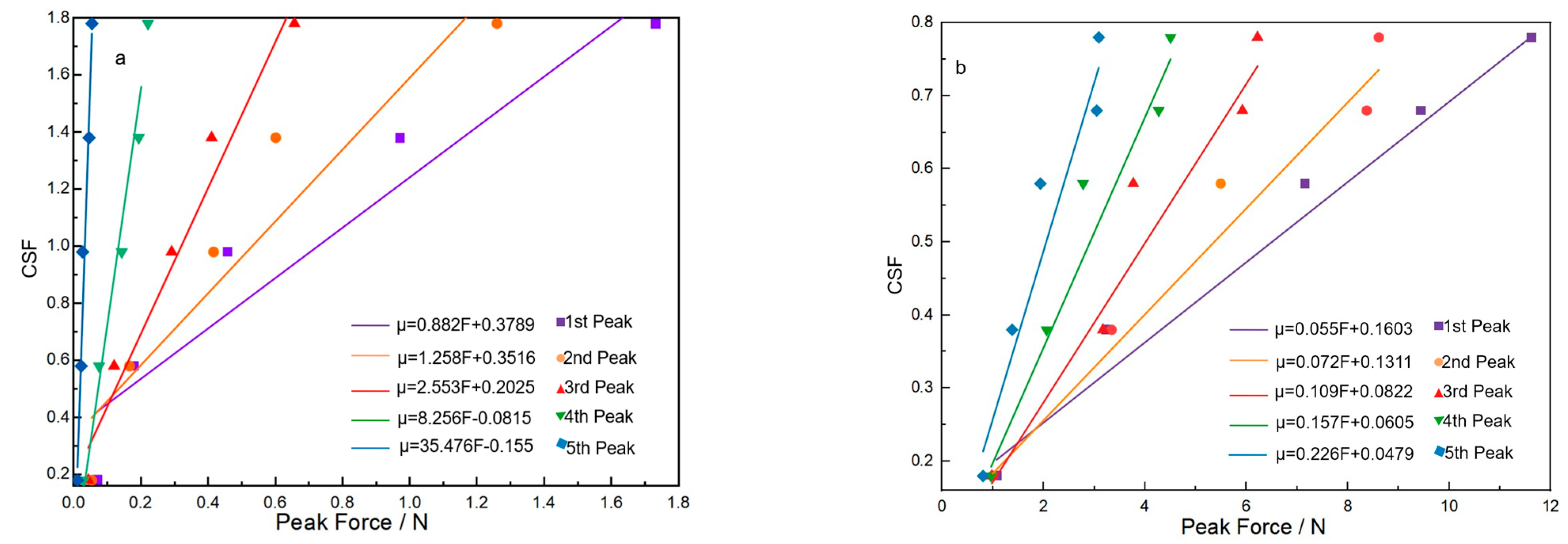

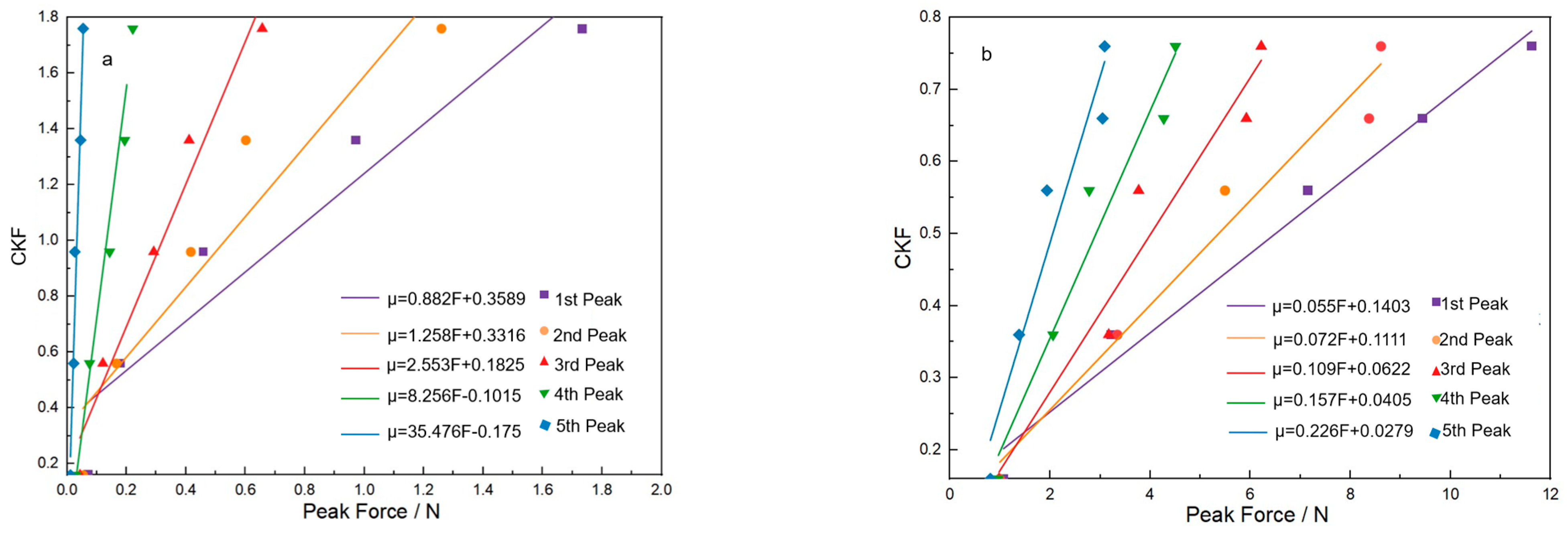

To simulate the ballistic performance of fabrics modified with nanomaterials through the FE method, we usually need to input the CIF. Chu et al. [

2] used the Coulomb friction to determine the CIF after TiO

2/ZnO treatment. Khodadadi et al. [

20] and Alikarami et al. [

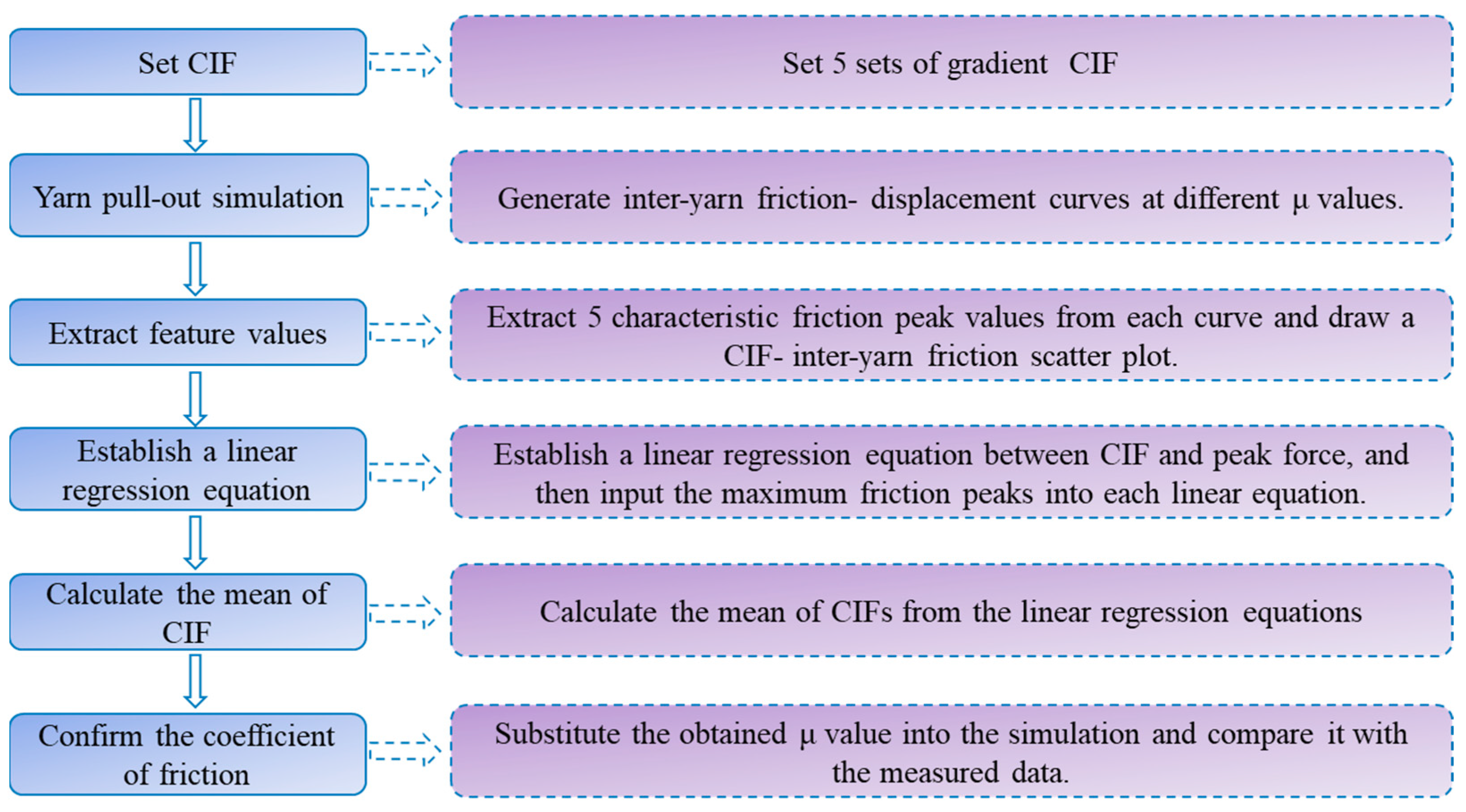

21] developed an analytical model for calculating the CIF in STF fabric based on the yarn pull-out force, number of crossovers in the direction of the pulled yarn, and normal load at each crossover. Previous studies have employed different approaches to determine the CIF in ballistic fabrics. López-Gálvez et al. [

22] proposed the linear method, which assumes a range of the CIF with specific gradients. These assumed coefficients are then input into a yarn pull-out finite element model, and linear regression is used to establish the relationship between the CIF and peak pull-out force, ultimately determining the friction coefficient range for modified plain weave fabrics. A novel measurement method was developed for carbon fiber bundles, detecting micro-forces of approximately 2 mN during fiber extraction while accounting for the bundle packing state (void fraction) and compressive stress (3–9 kPa). Stable measurements were obtained at fiber bundle volume fractions between 0.4 and 0.5, yielding a dynamic friction coefficient of 0.13 ± 0.1. Furthermore, based on Howell’s power law [

23], Vu et al. [

24] proposed an anisotropic friction model. By employing a constant-force spring device to maintain a consistent contact area, they achieved a precise measurement of the CIF. The experimental study utilized a combination of carbon fibers and glass fibers. Tests conducted under both dry and wet conditions revealed that both the yarn intersection angle and normal force significantly influenced the friction coefficients. Notably, under wet conditions, the capillary forces generated by water bridges between fibers resulted in a higher CIF compared to dry conditions.

It should be noted that existing studies have primarily focused on plain weave fabrics. Currently, no studies that evaluate the CIF of surface-modified aramid sateen fabrics have been found. This paper aims to accurately determine the friction coefficients for sateen fabrics, providing valuable reference data for further research in ballistic protection and related fields. The findings will contribute to a better understanding of sateen fabric behavior under ballistic impact and support the development of more accurate simulation models for protective applications.

6. Conclusions

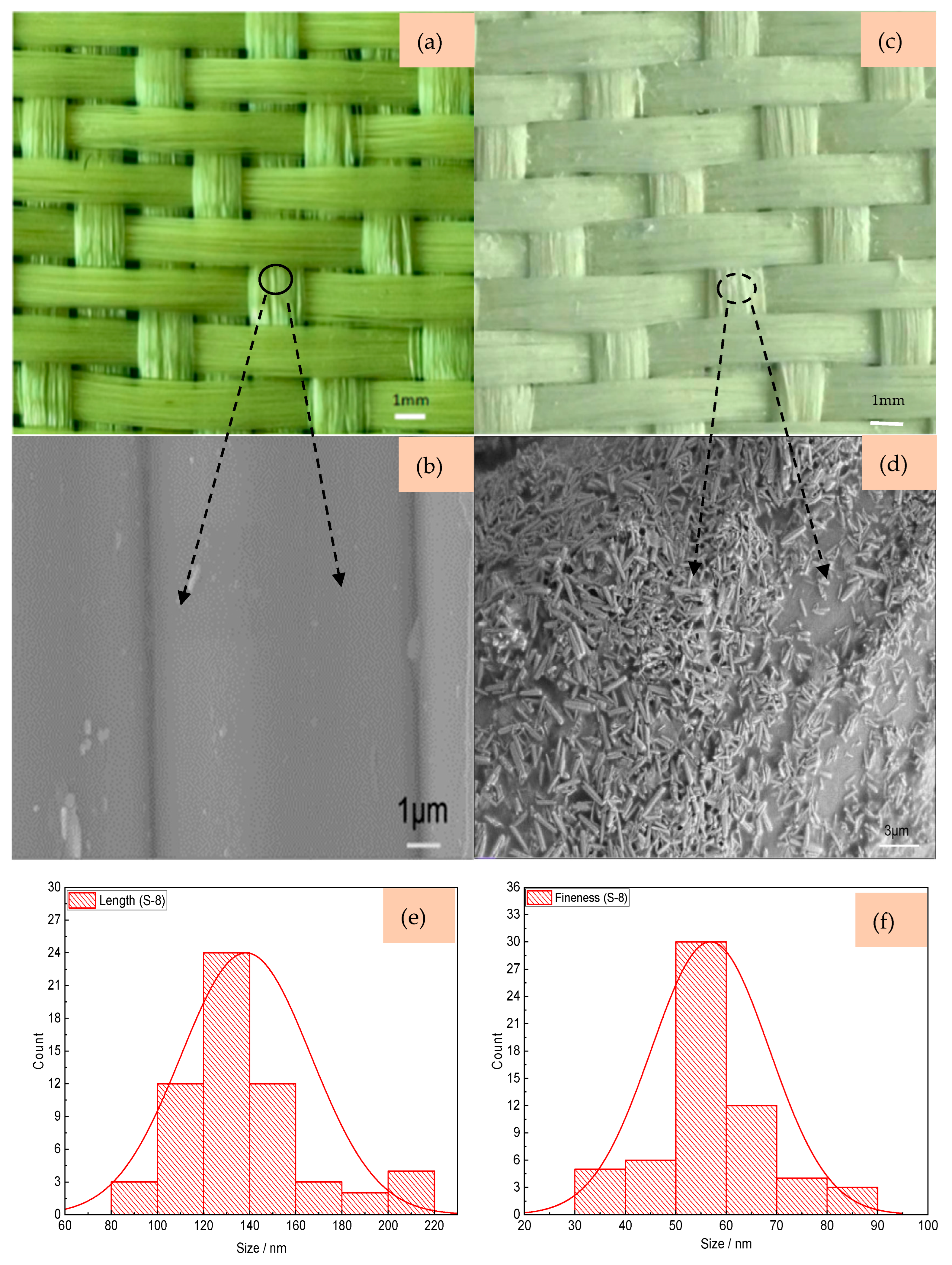

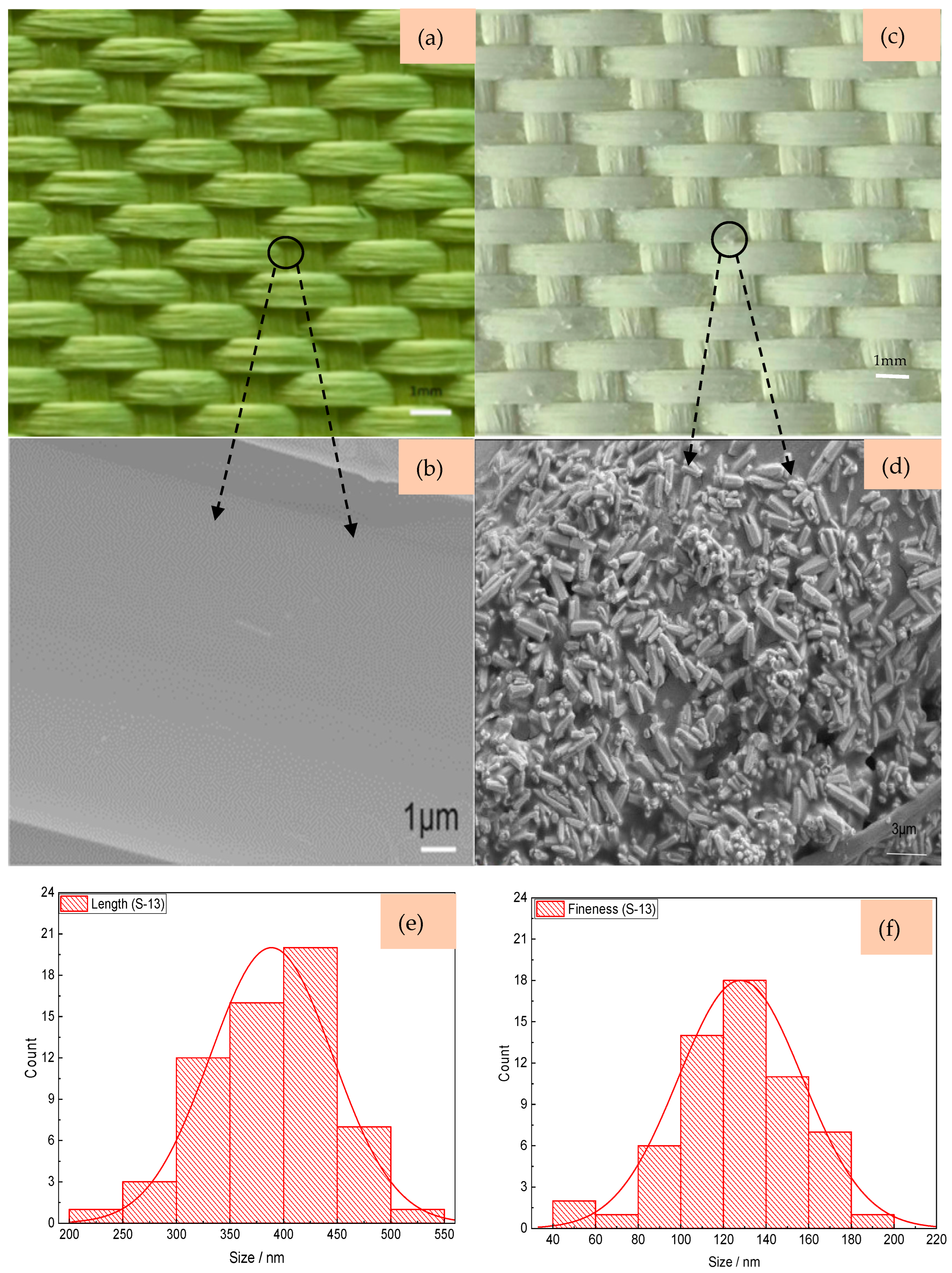

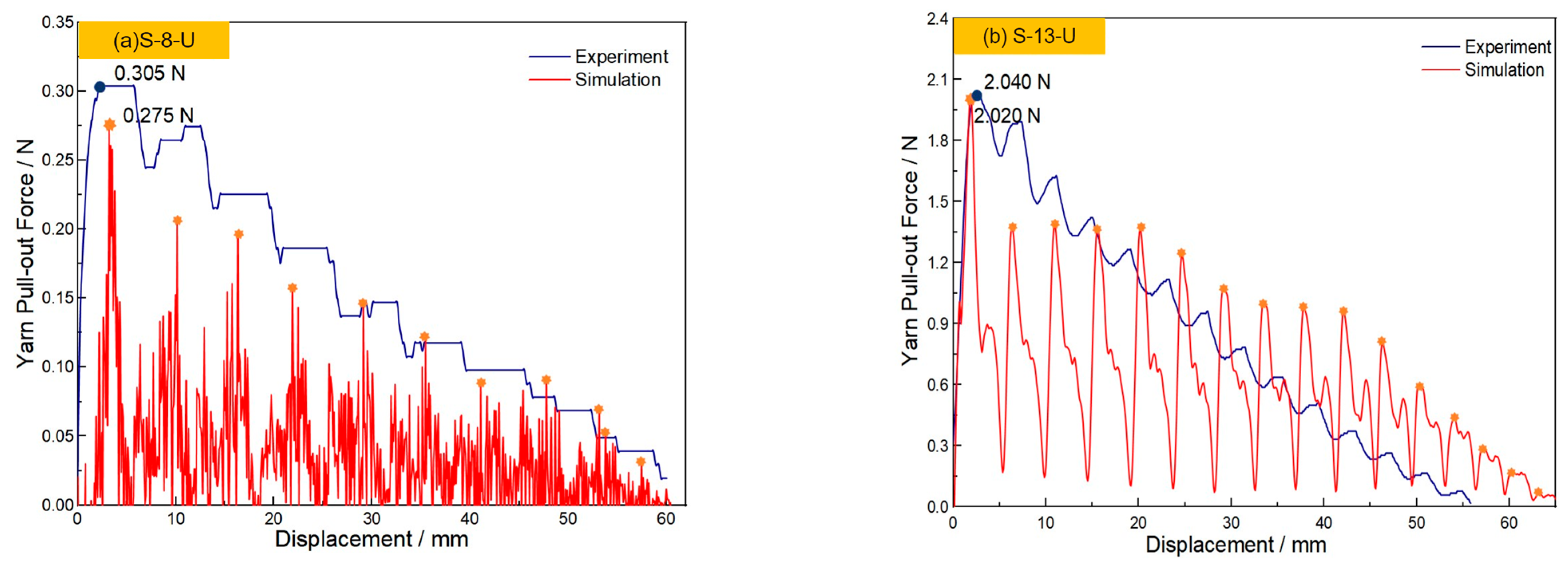

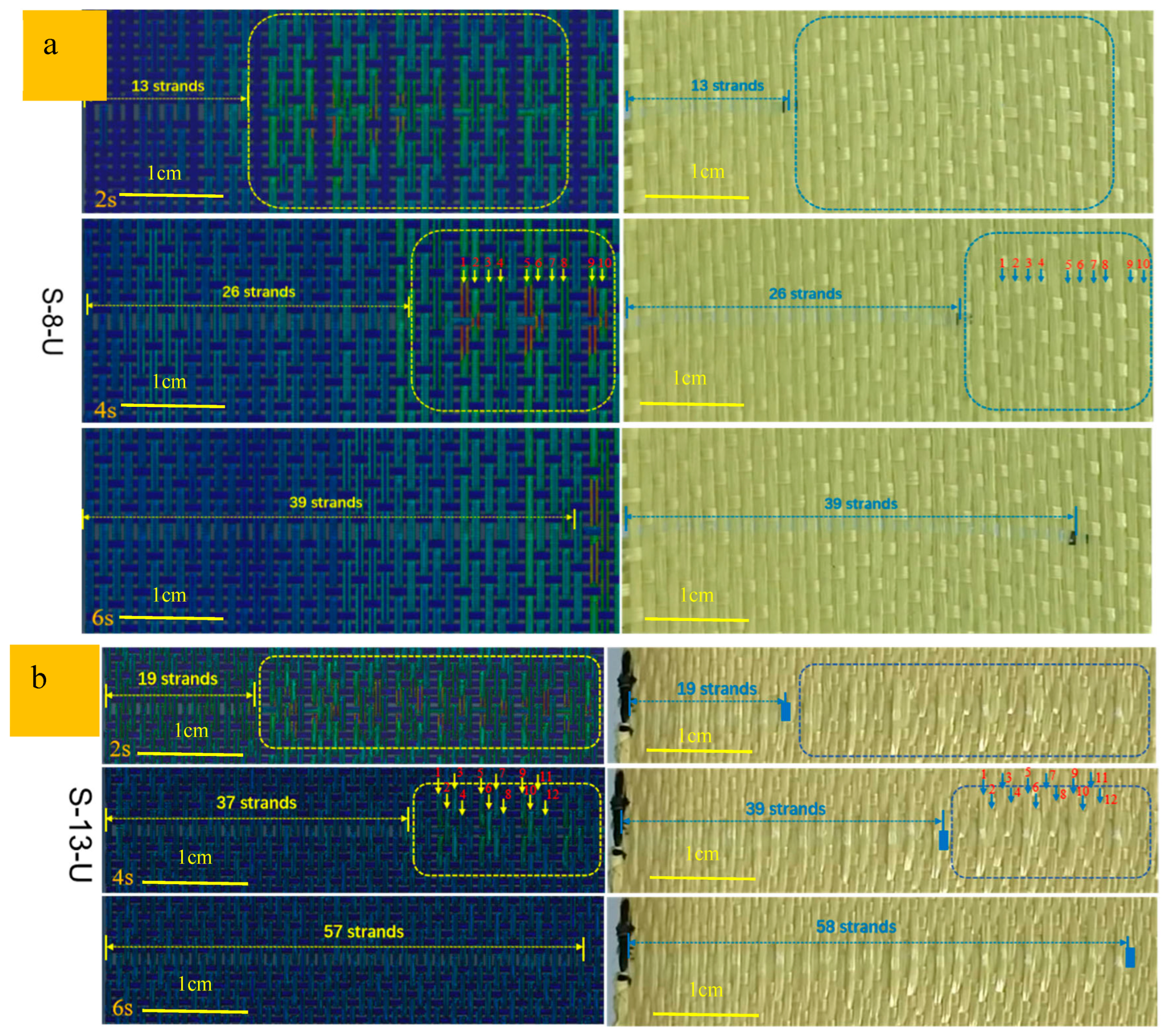

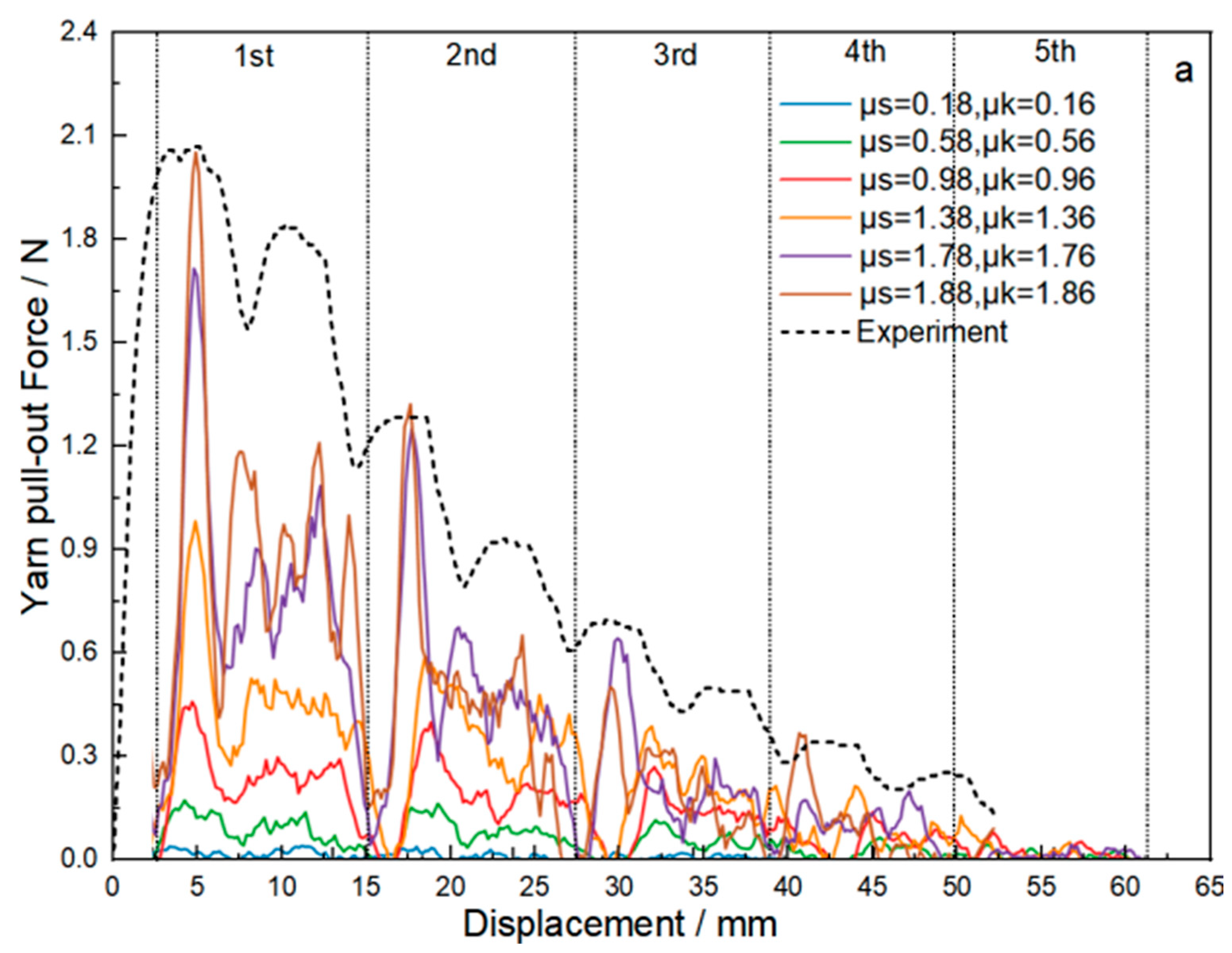

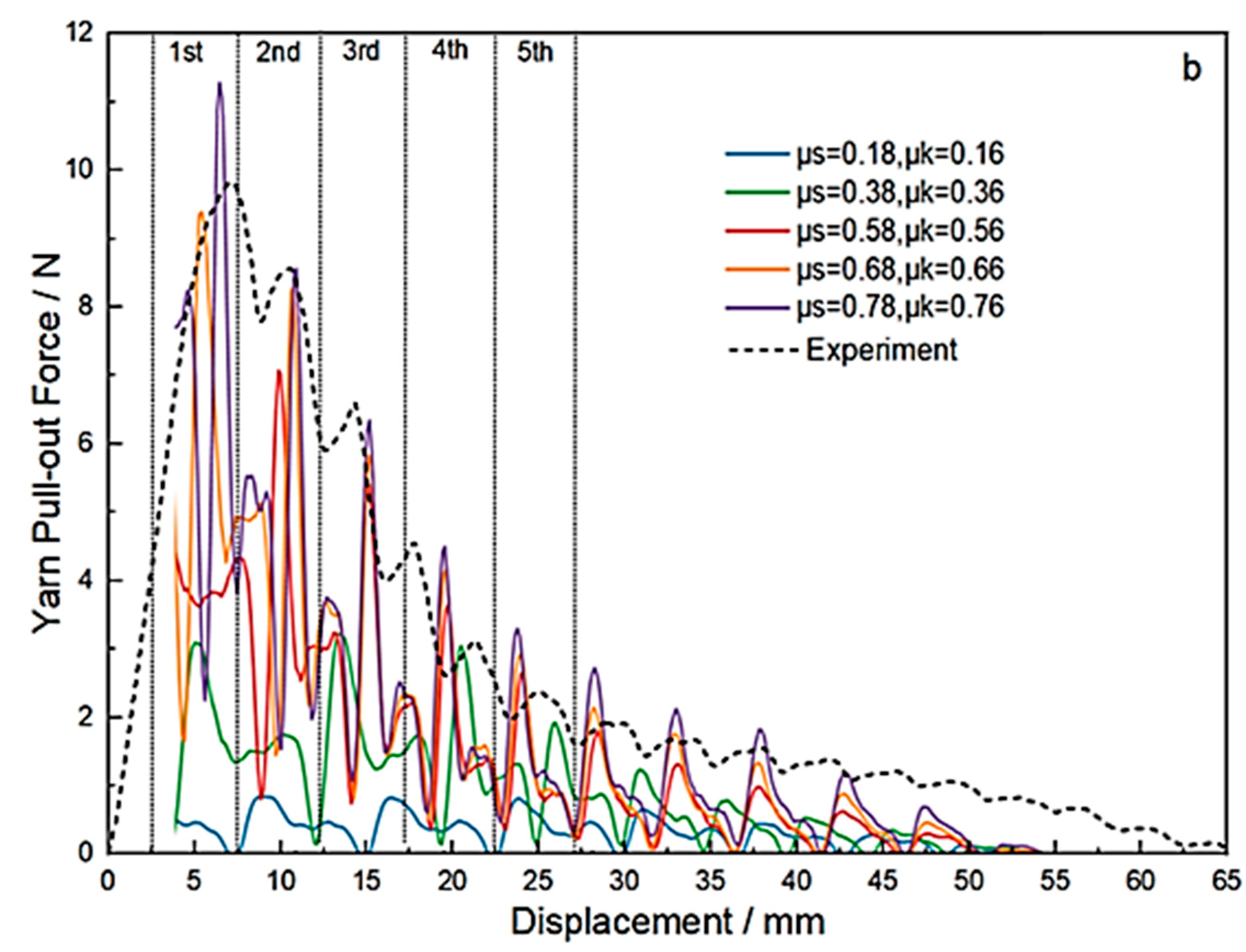

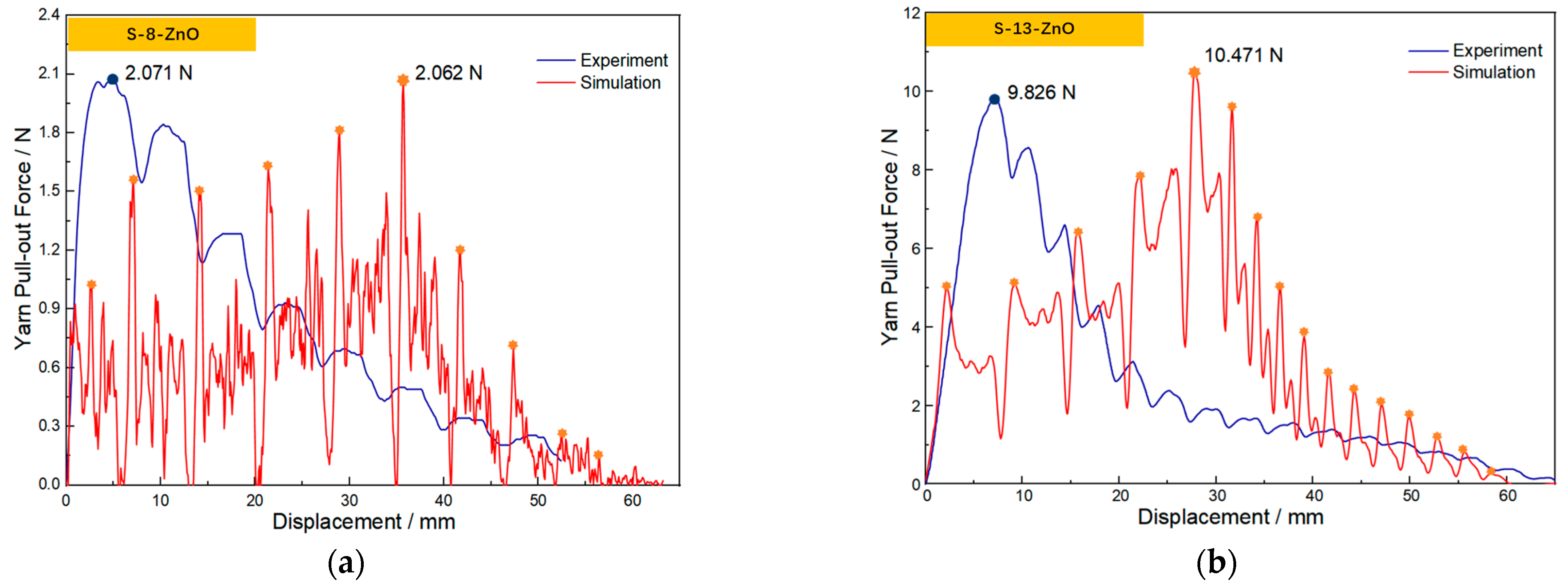

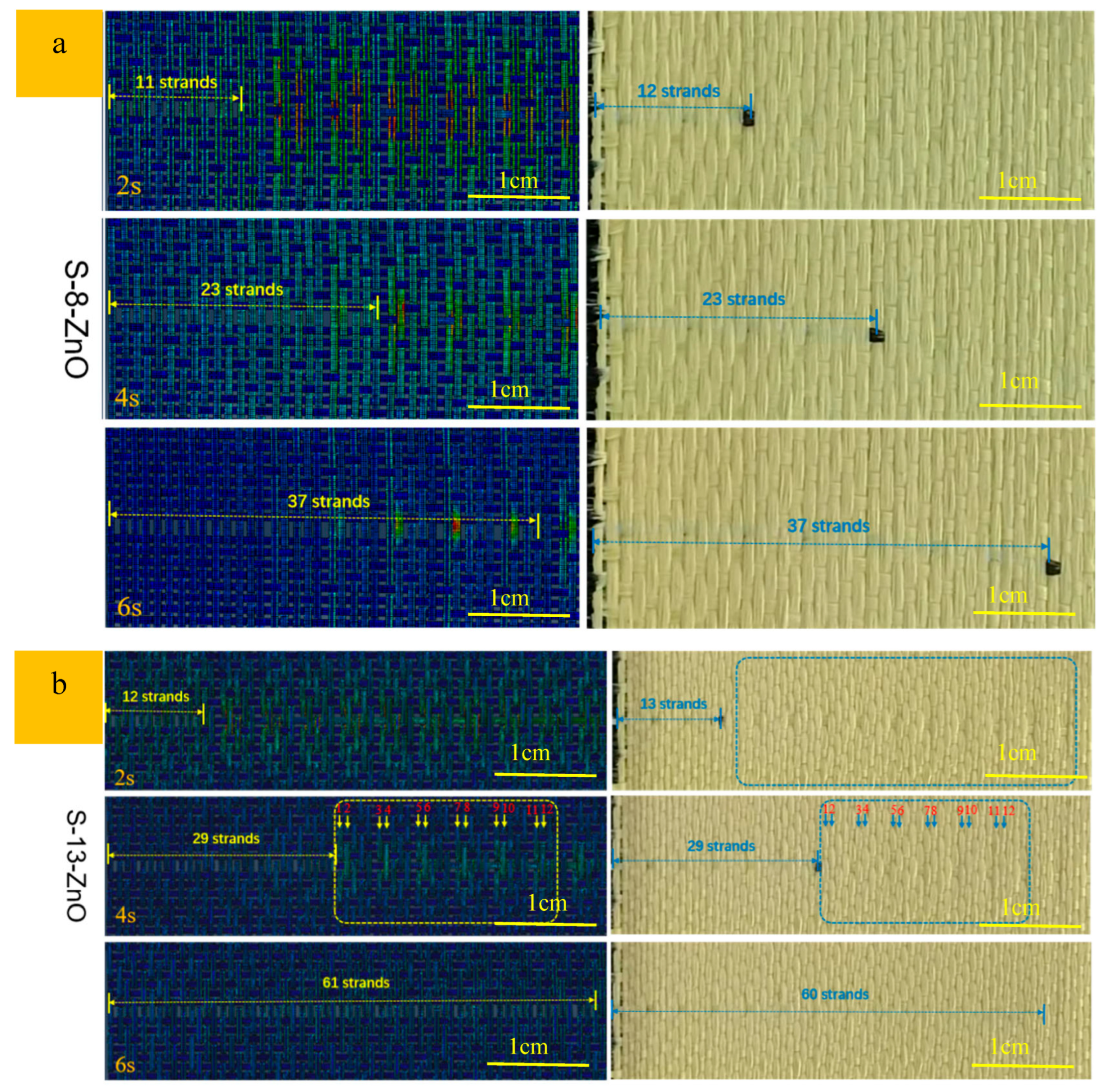

This paper studies the method for determining the CIF of sateen fabrics with different thread densities after ZnO nanowire growth. Through an analysis of the accuracy of the linear method, the following conclusions are drawn:

The CSF and CKF of S-8-ZnO sateen fabric obtained by the linear method are 1.85 and 1.83, respectively, while those of S-13-ZnO sateen fabric are 0.76 and 0.74, respectively. When inputting these CIFs into the yarn pull-out models of the two sateen fabrics, the error between the simulated peak pull-out force and the experimentally measured pull-out force is 0.43% for S-8-ZnO fabric and 6.56% for S-13-ZnO fabric. In summary, the linear method is suitable for evaluating the CIF of sateen fabrics treated with nanowires and is of great significance for subsequent finite element analyses of the ballistic impact. The current research has verified how to accurately obtain the CIF of sateen fabric with ZnO nanowire, which provides a key parameter input method for the finite element method to study the ballistic impact performance of modified fabric. The linear regression method established in this study is not only suitable for sateen fabric with ZnO nanowires, but it can also be applied to other fabric structures, such as plain weave, twill, and so on. In future studies, the method used in this paper can be integrated into the multi-scale finite element model, providing more accurate parameter support for ballistic impact simulations of bulletproof fabrics.