Quantitative Evaluation of the Blending Between Virgin and Aged Aggregates in Hot-Mix Recycled Asphalt Mixtures

Abstract

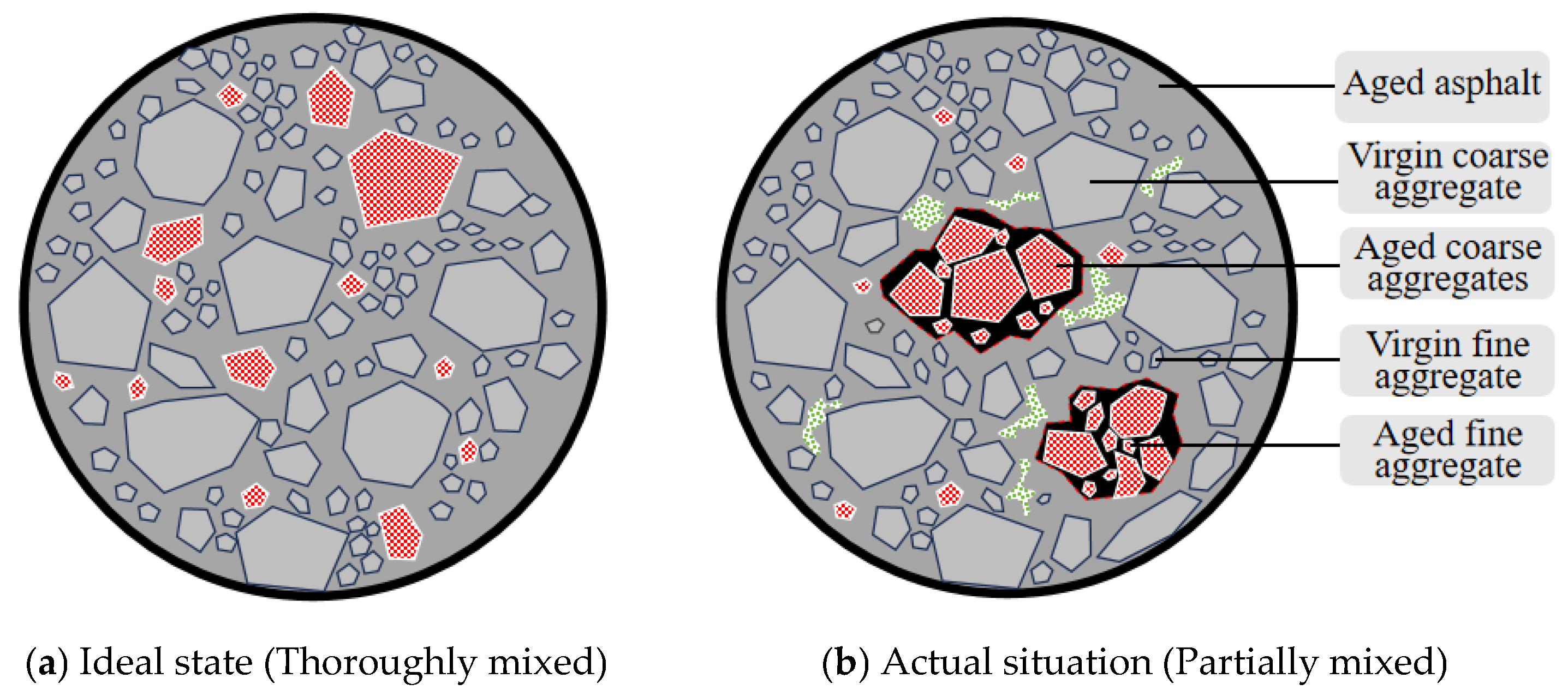

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Experimental Design

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Virgin Asphalt

2.1.2. Virgin Aggregates

2.1.3. RAP

2.2. Experimental Procedure

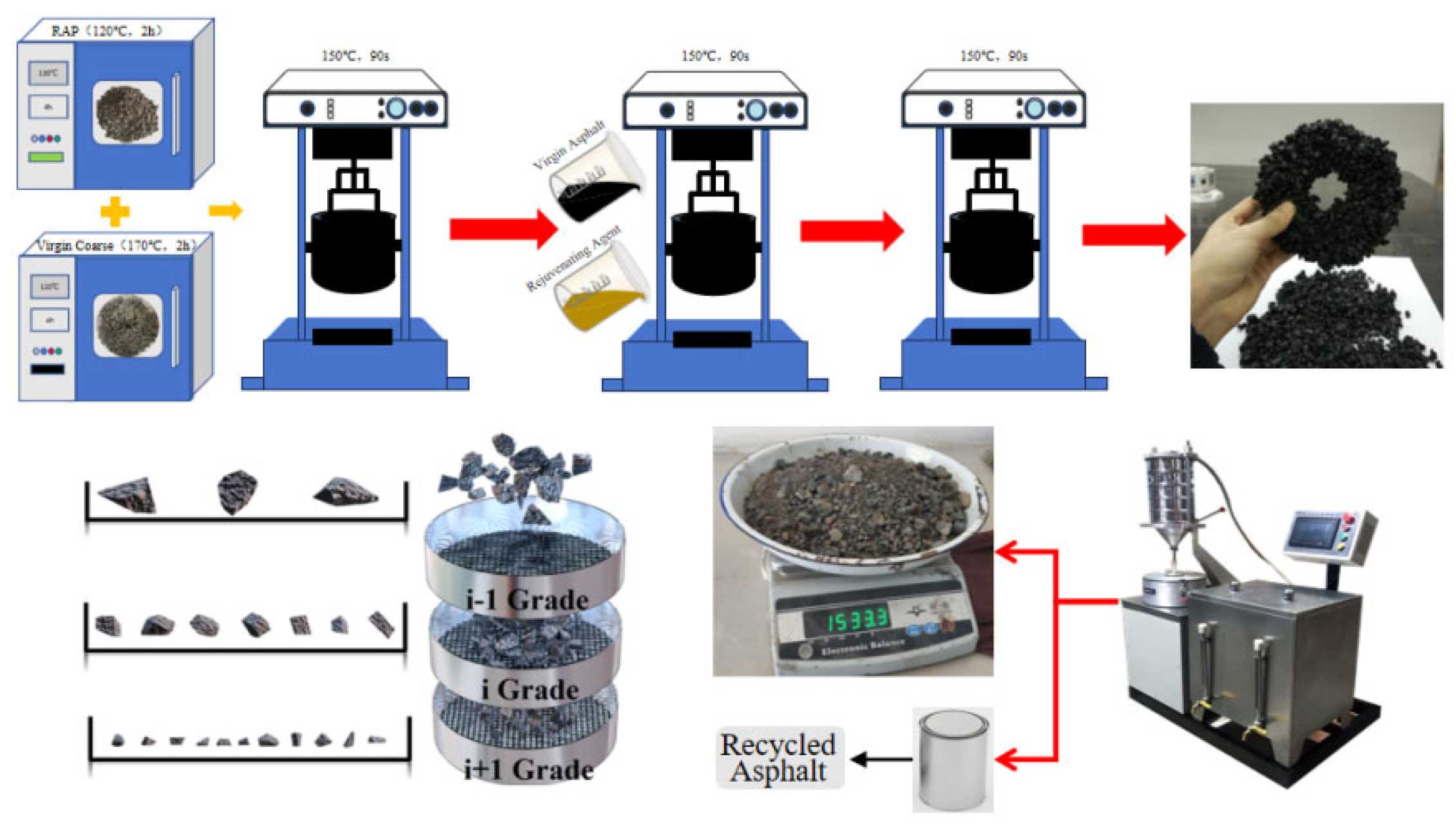

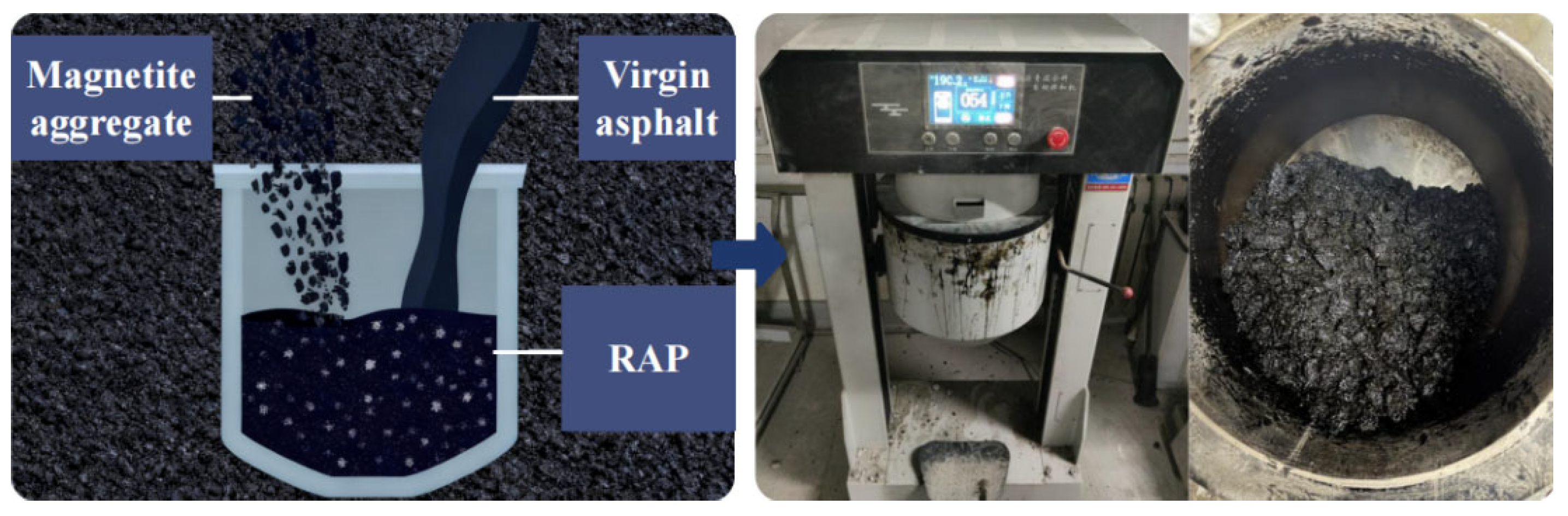

2.2.1. Preparing Asphalt Mixtures

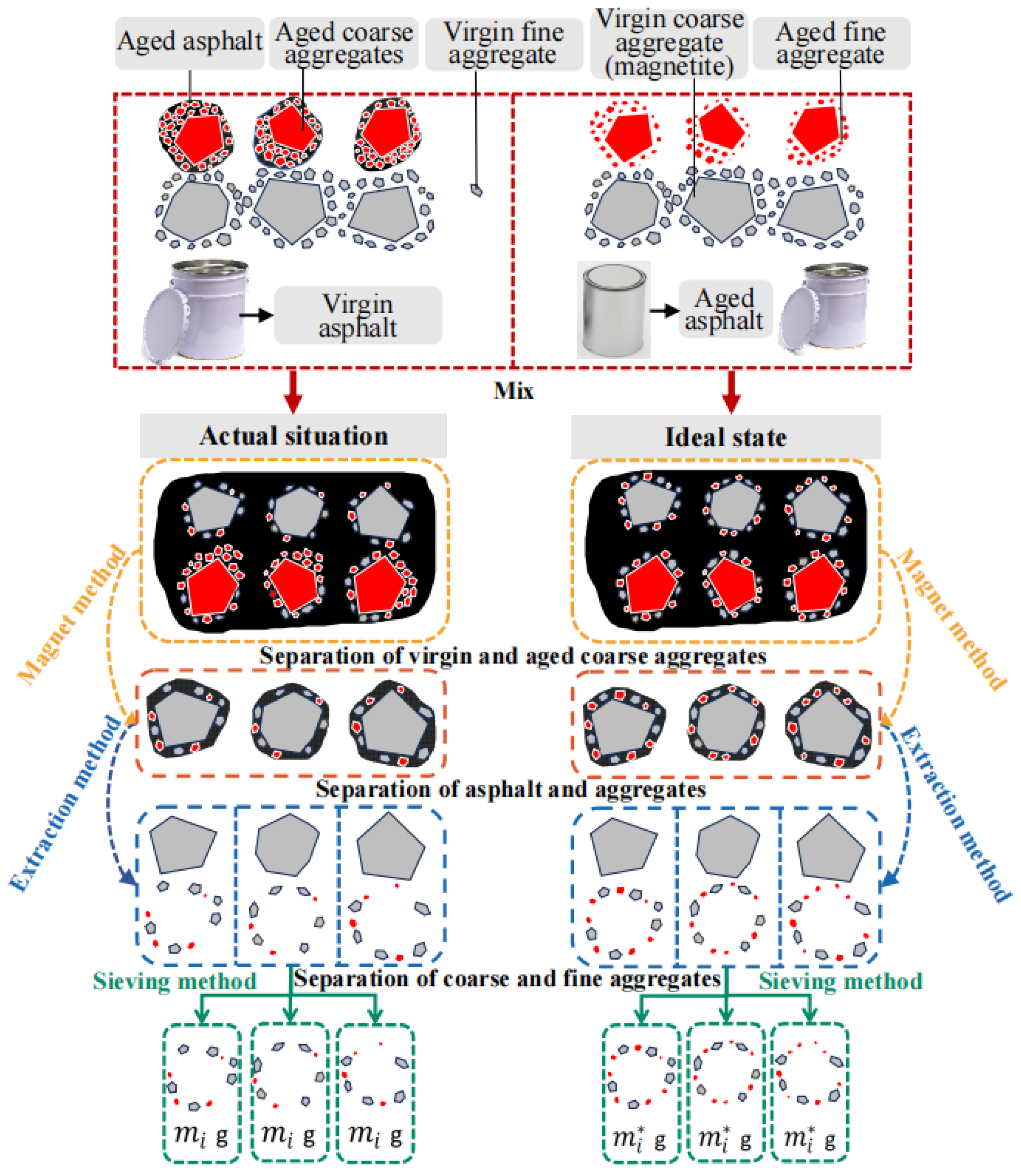

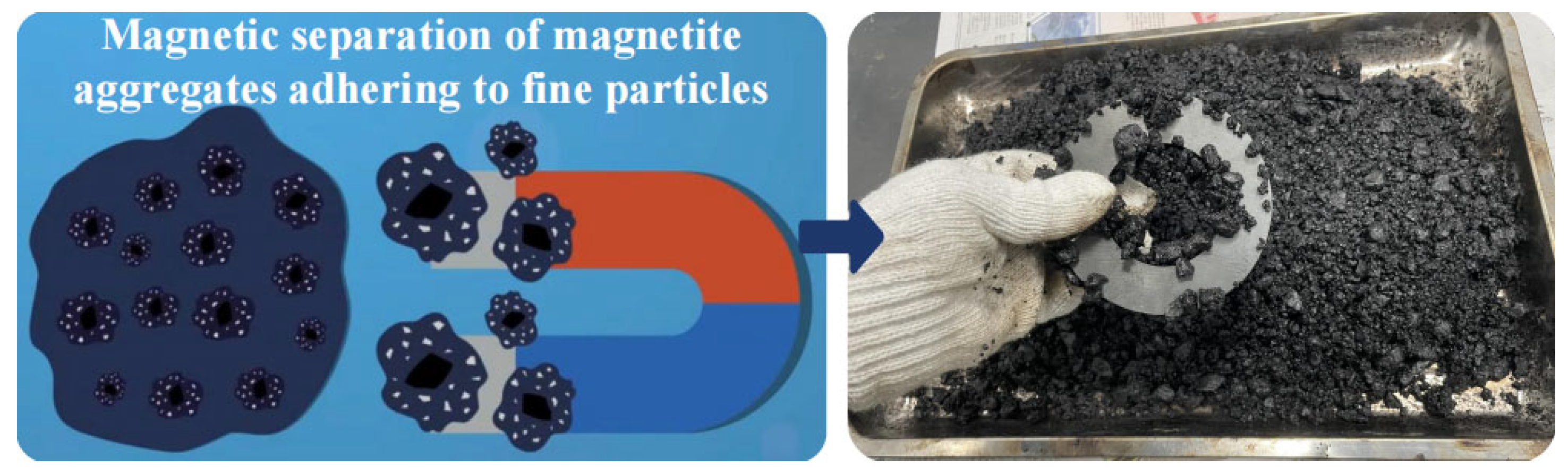

2.2.2. Separating Virgin and Aged Materials

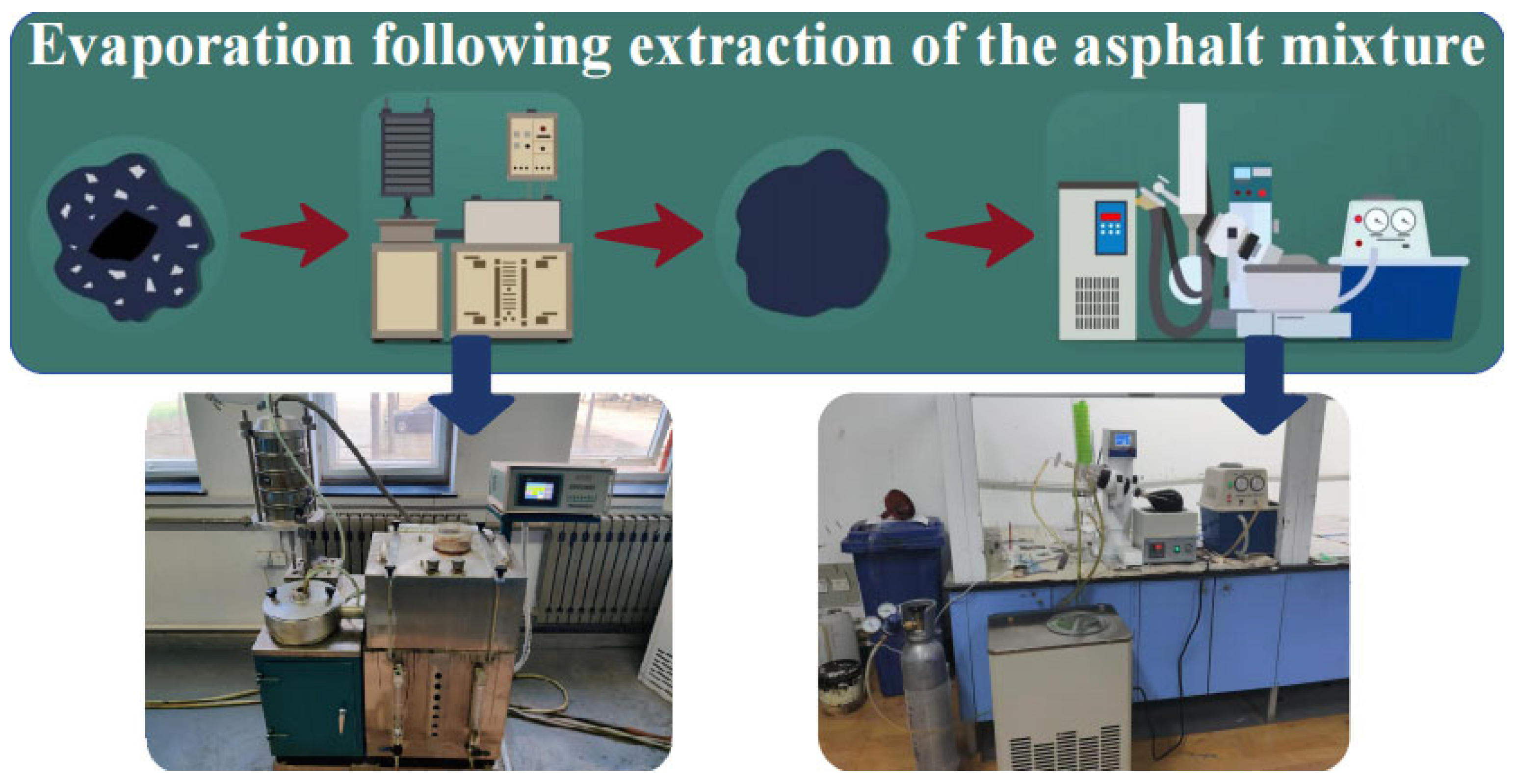

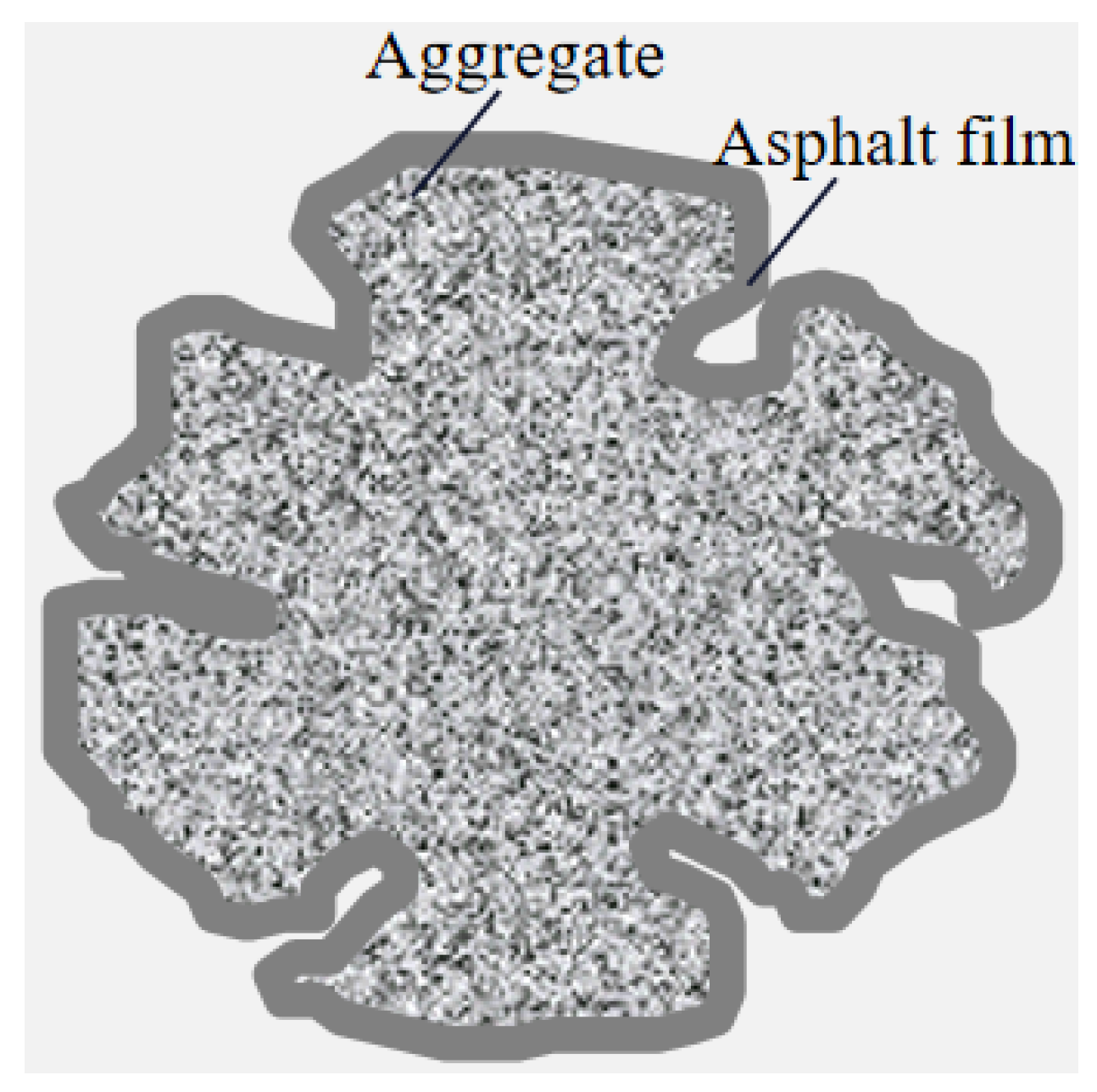

2.2.3. Separating Asphalt from Aggregates

2.2.4. Calculating the Blending Degree

2.3. Experimental Design

3. Results and Discussion

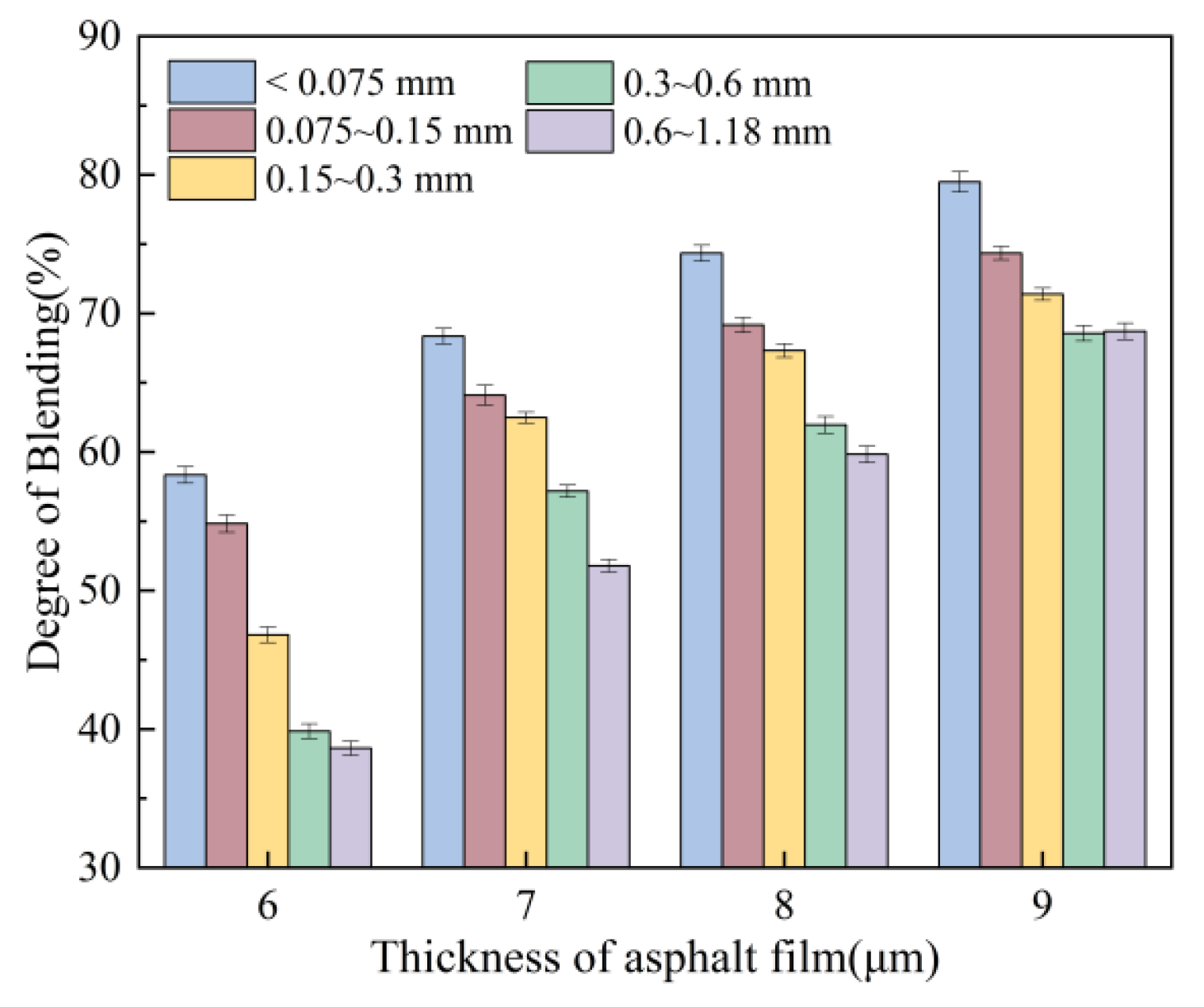

3.1. Effect of Experimental Parameters on Degree of Blending

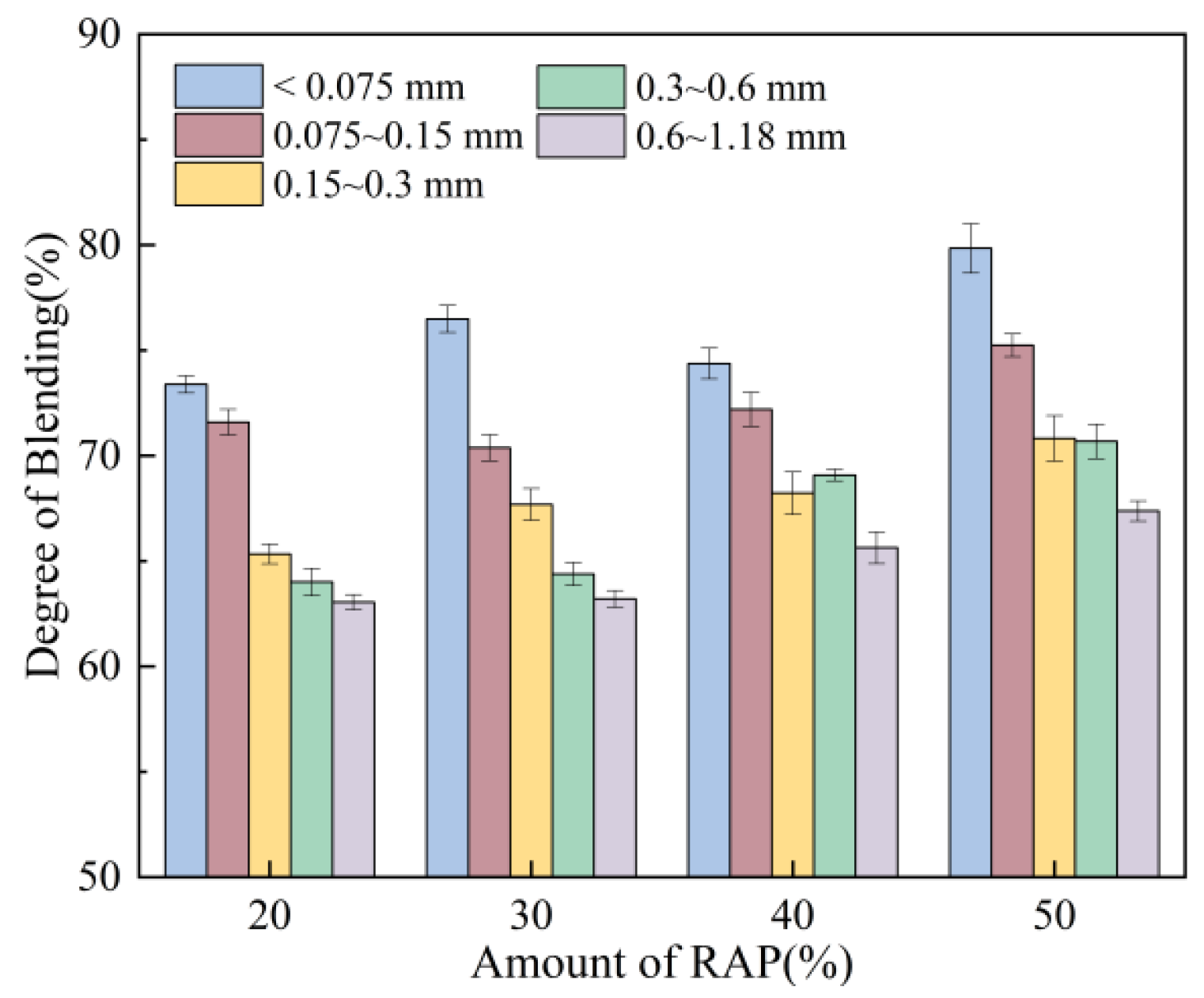

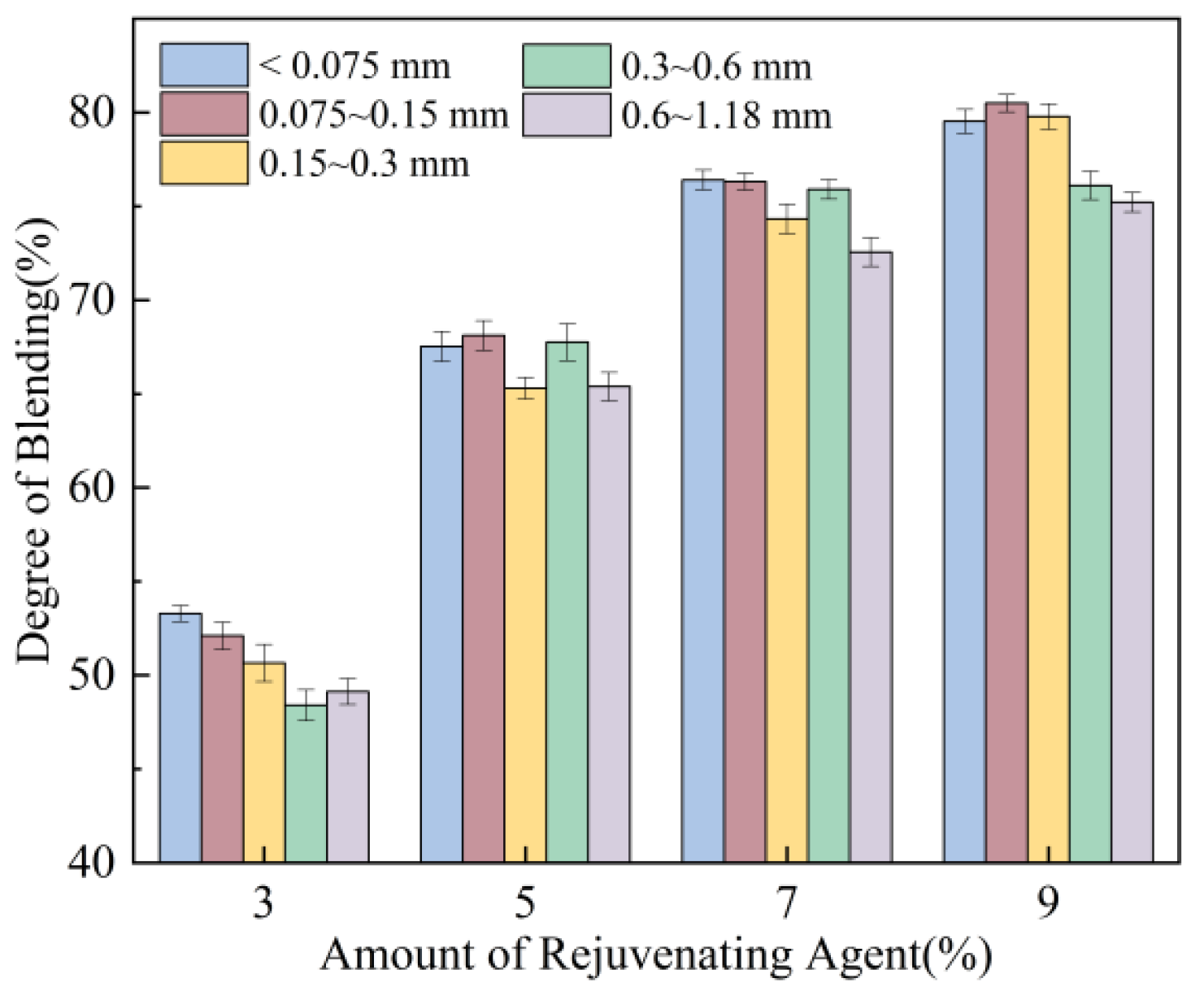

3.1.1. Effect of Amount of RAP and Rejuvenating Agent

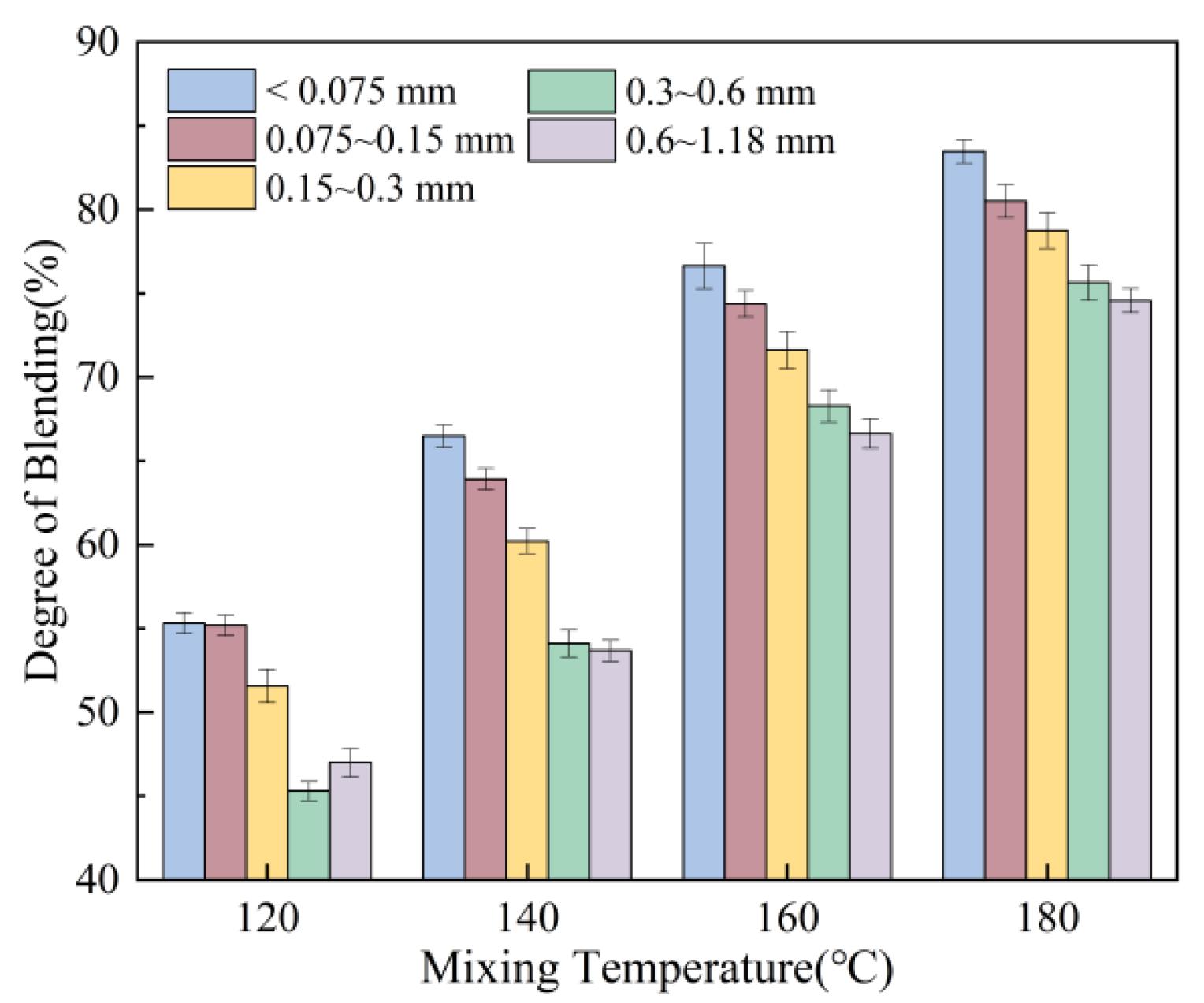

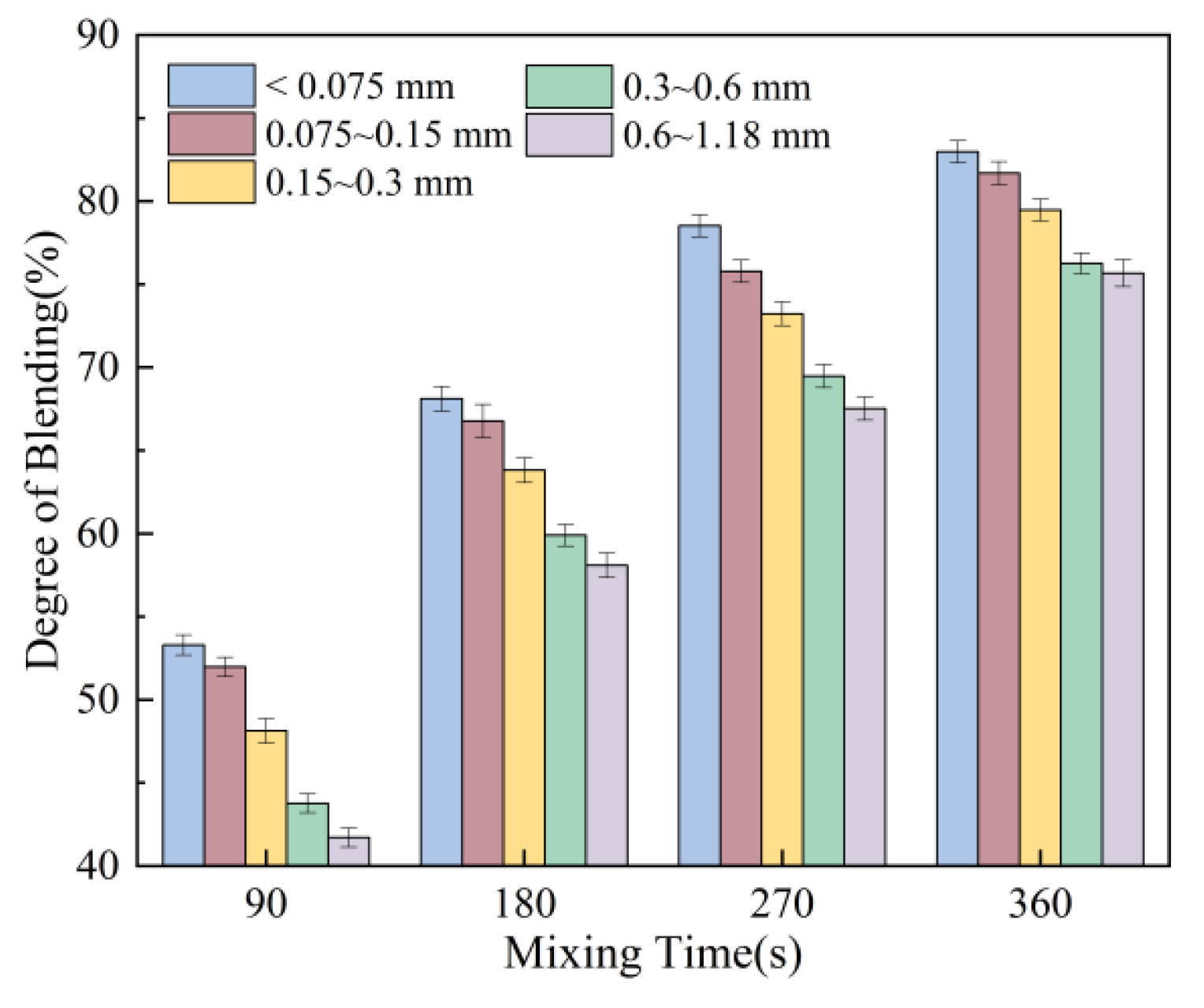

3.1.2. Effect of Mixing Temperature and Mixing Time

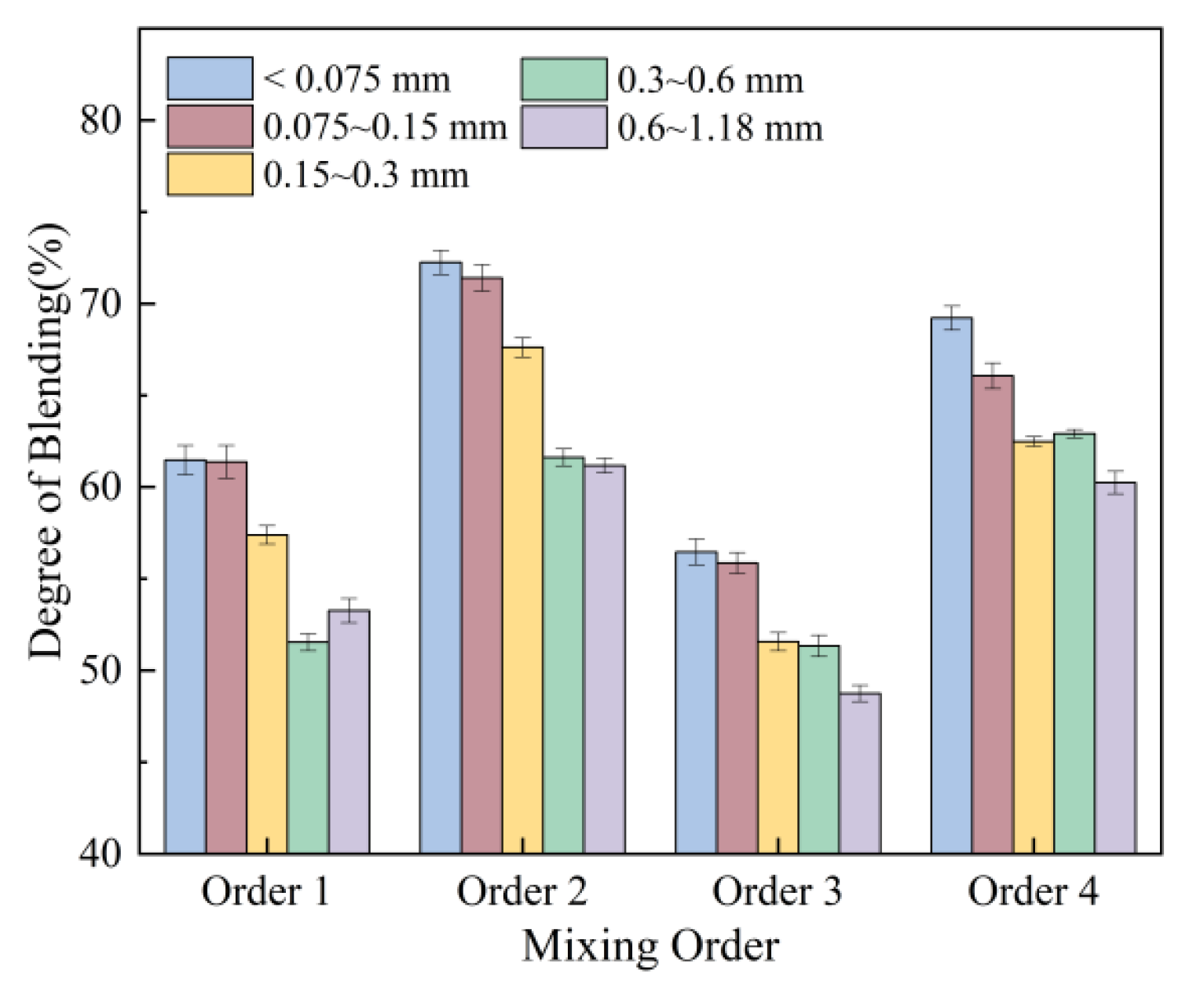

3.1.3. Effect of Mixing Order and Asphalt Content

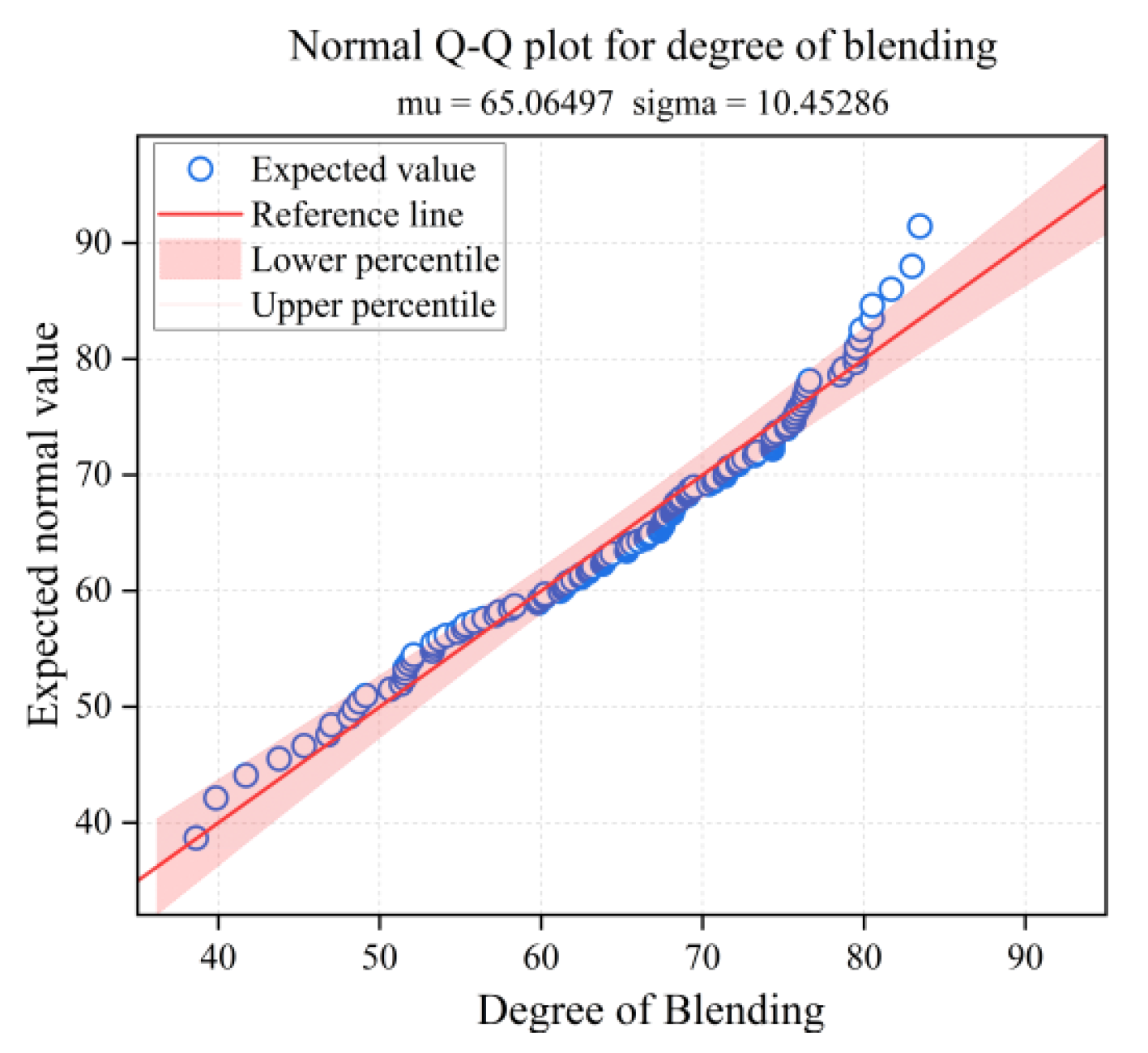

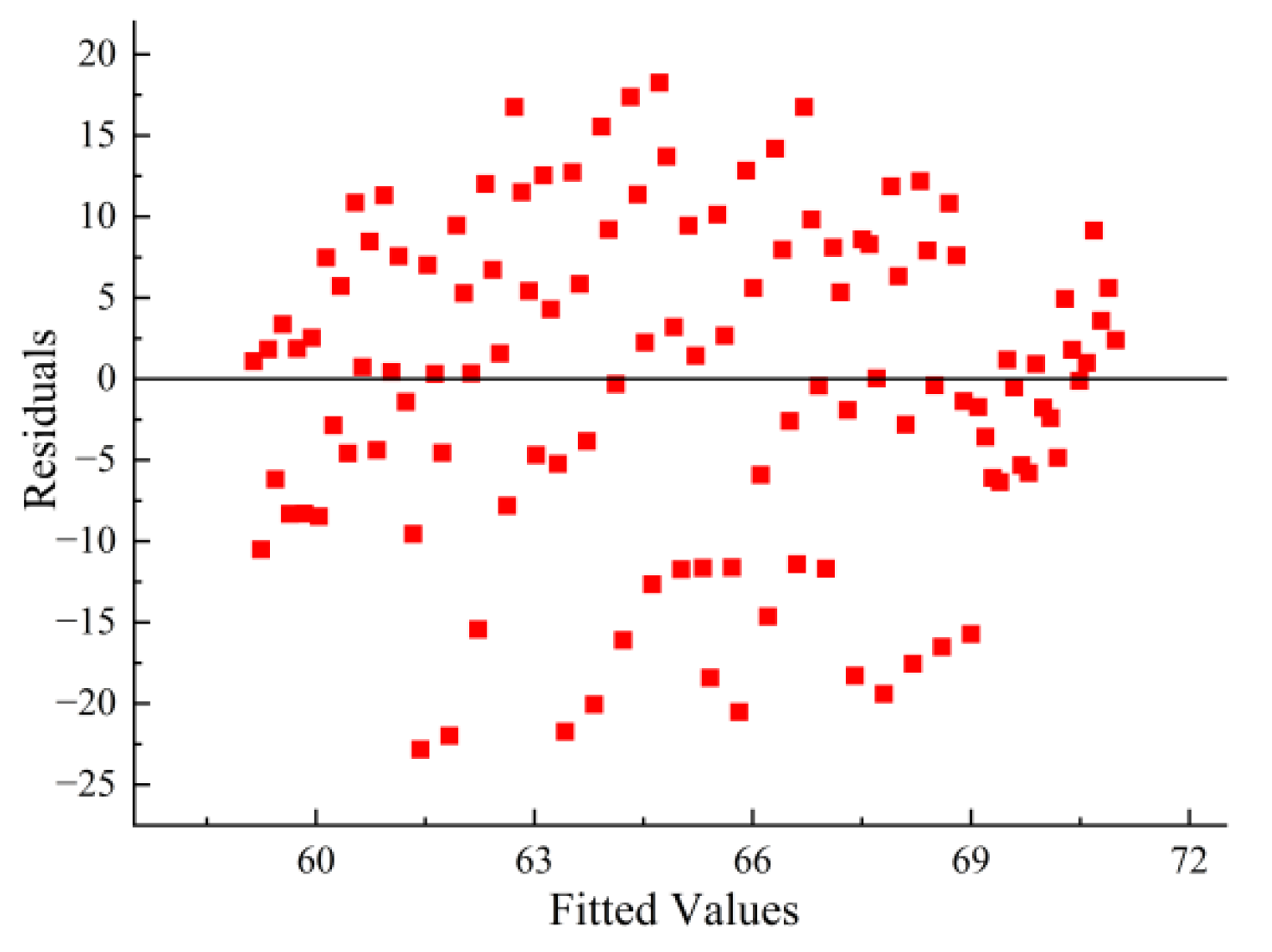

3.2. Analysis of Variance

3.3. Blending Rules of Virgin and Aged Aggregates

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dong, P.; Yuan, Y.; Cao, X. Numerical investigation of dynamic stresses in asphalt pavement under the combined action of temperature, moisture and traffic loading. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 417, 135131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Ren, X.; Jiao, Y.B.; Lian, M.S. Review of Aging and Antiaging of Asphalt and Asphalt Mixture. China J. Highw. Transp. 2022, 35, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellner, F.; Liang, N.X. Structure ife of Highway Pavement. J. Chongqing Jiaotong Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2018, 37, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Q.; Tang, B.M.; Yang, X.Y.; Li, J.; Cao, X.J.; Zhu, H.Z. Risk assessment of volatile organic compounds from aged asphalt: Implications for environment and human health. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 440, 141001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Huang, Z.; He, X.; Su, Y.; Chen, W.; Chen, S.; Jin, Z.; Qi, H.; Tian, C.; Liu, Q. Treating waste with waste: Innovative application of maltenes derived from reclaimed asphalt for the efficient rejuvenation of aged asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 477, 141385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, H.A.; Manasrah, A.D.; Carbognani, L.; Sebakhy, K.O.; Nokab, M.E.H.E.; Hacini, M.; Nassar, N.N. A study on the characteristics of Algerian Hassi-Messaoud asphaltenes: Solubility and precipitation. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2022, 40, 1279–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, L.; Huang, W.; Wang, H. Study on the mixing process improvement for hot recycled asphalt mixture. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 365, 130068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.X.; Ma, Y.T.; Zheng, K.P.; Cheng, Z.Q.; Xie, S.J.; Xiao, R.; Huang, B.S. Quantifying the agglomeration effect of reclaimed asphalt pavement on performance of recycled hot mix asphalt. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 442, 141044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.T.; Jiao, Y.; Xia, X.Q.; Yang, S.; Wang, Z.X. Analysis on cluster quantification in hot recycled asphalt mixtures based on sieve tests. J. Southeast Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 52, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Yang, R.; Yang, J.; Fan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tan, J.H. Effect of degree of blending on the fatigue performance of epoxy-recycled mixtures with high reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) content. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 489, 142227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.Z.; Zhang, Y.; Sang, T.; Ye, S.; Gong, Z.; Ding, W.; Chen, H. Research on the Influence of High RAP Contenton Road Performance of Hot-in-place Recycled Asphalt Mixtur. Highway 2025, 70, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Yu, X.; Dong, F.; Zu, Y.; Huang, J. Influence of asphalt mixture workability on the distribution uniformity of asphalt, aggregate particles and asphalt film during mixing process. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 377, 131128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, Y.; Huang, S. Accurate detection and evaluation method for aggregate distribution uniformity of asphalt pavement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 152, 715–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yuan, L.; Wang, Z.; Jing, H.; Shao, T.; Chen, H. A new method for evaluating the uniformity of steel slag distribution in steel slag asphalt mixture based on deep learning. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 400, 132766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Sun, L.J.; Yang, Y.L.; Dong, R.K. A New Way to Study Homogeneity of HAM Based on Digital Image Disposal Technology. J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev. 2004, 21, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Sun, L.J.; Dong, R.K. Discussion about New Method for Evaluating Homogeneity of Hot-mix Asphalt. J. Tongji Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2005, 173, 166–168+173. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Sun, L.J.; Wang, Y.Q.; Shi, Y.J. Application of digital i mage processing in evaluating homogeneity of asphalt mixture. J. Jilin Univ. (Eng. Technol. Ed.) 2007, 37, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.L.; Liang, N.X.; Zeng, S. Influence of Acquisition Methods on Segregation Evaluation of Digital Image of Asphalt Mixture. J. Chongqing Jiaotong Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2021, 40, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.S.; You, Z.P.; Tan, Y.Q.; Zhao, Y.H.; Jing, H.L. Evaluation Method for Homogeneity of Asphalt MixturesBased on CT Technique. China J. Highw. Transp. 2017, 30, 1–9+55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Huang, W.; Lv, Q. Study on bond properties between RAP aggregates and virgin asphalt using Binder Bond Strength test and Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 124, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, S.; Lu, C.; Shi, J.; Yang, X.; Yang, M. Multi-scale investigation of temperature, water intrusion, rubber content, and bitumen aging effects on fluorescence tracing characteristics of bitumen. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 487, 142059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.W.; Ma, T.; Bian, G.J.; Jin, J.; Huang, X.M. Proposed Testing Procedure for Estimation of Effective Reeycling Ratio of Aged Asphalt in Hot Recycling Technical Conditions. J. Build. Mater. 2011, 14, 418–422. [Google Scholar]

- Navaro, J.; Bruneau, D.; Drouadaine, I.; Colin, A.; Cournet, J. Observation and evaluation of the degree of blending of reclaimed asphalt concretes using microscopy image analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 37, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Jiang, J.; Liu, T.; Zhou, Z. Investigation of the homogeneity of aggregate contact characteristics and thickness distribution of mortar in hot recycled asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 478, 141448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Li, N.; Zhan, H.; Yu, X.; Wang, Z.Y. Evaluation of Aggregate Dispersion Uniformity of Reclaimed Asphalt Mixtures Using DIP Technique. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2022, 34, 04022290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Li, N.; Yu, X.; Xie, Z.; Wang, D. Aggregate uniformity of recycled asphalt mixtures with RAP from refined decomposition process: Comparison with routine crushing method. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 442, 137665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.L.; Huang, G.; He, Z.Y.; Wang, G.W.; Chen, X.Y. Influence of RAP Segregation on Performance of Recycled Asphalt Mixture. J. Chongqing Jiaotong Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2013, 32, 953–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.L.; Huang, X.M. Evaluation of dispersive performance of asphalt mixture during mixing of hot in-place recycling. J. Harbin Inst. Technol. 2011, 43, 128–131. [Google Scholar]

- JTG E20-2011; Standard Test Methods of Bitumen and Bituminous Mixtures for Highway Engineering. Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2011.

- Guo, D.D.; Sha, A.M. Techniques for snow-melting and deiced based on microwave and magnet coupling effect. J. Shandong Univ. (Eng. Sci.) 2012, 42, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JTG F40-2004; Technical Specifications for Construction of Highway Asphalt Pavements. Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2004.

- Li, M.; Liu, L.; Xing, C.; Liu, L.; Wang, H. Influence of rejuvenator preheating temperature and recycled mixture’s curing time on performance of hot recycled mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 295, 123616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazi, A.; Alaa, S.; Waleed, Z.; Helal, E. Microscopy-based approach for measuring asphalt film thickness and its impact on hot-mix asphalt performance. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e01711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Jiang, W.; Xiao, J.; Guo, D.; Yuan, D.; Wu, W.; Wang, W. Study on the blending behavior of asphalt binder in mixing process of hot recycling. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Testing Index | Test Method [29] | Technical Requirements | Virgin Asphalt |

|---|---|---|---|

| Penetration (25 °C, 100 g, 5 s, 10−1 mm) | T 0604-2011 | 60~80 | 71.3 |

| Ductility (5 cm/min, 10 °C, cm) | T 0605-2011 | ≥25 | 34.5 |

| Softening point (ring and ball method, °C) | T 0606-2011 | ≥46 | 50.7 |

| Density (15 °C, g·cm−3) | T 0603-2011 | — | 1.048 |

| Testing Index | Technical Requirements | Test Results |

|---|---|---|

| Crushing value (%) | ≤28 | 10.2 |

| Los Angeles coefficient (%) | ≤30 | 8.9 |

| Apparent specific gravity (g/cm3) | ≥2.5 | 3.91 |

| Water absorption (%) | ≤3.0 | 0.34 |

| Ruggedness (%) | ≤12 | 0.3 |

| Adhesion to asphalt | ≥4 | Level 5 |

| Polished stone value | ≥42 | 44 |

| Testing Index | Test Method [29] | Technical Requirements | Aged Asphalt |

|---|---|---|---|

| Penetration (25 °C, 100 g, 5 s, 10−1 mm) | T 0604-2011 | 60~80 | 30.8 |

| Ductility (5 cm/min, 10 °C, cm) | T 0605-2011 | ≥25 | 2.3 |

| Softening point (ring and ball method, °C) | T 0606-2011 | ≥46 | 66.4 |

| Density (15 °C, g·cm−3) | T 0603-2011 | — | 1.042 |

| Screen Hole Diameter | 10~20 mm | 5~10 mm | 0~5 mm | Fillers | 0~10 mm RAP | 10~20 mm RAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26.5 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 19 | 90.3 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 16 | 62.7 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 97.4 |

| 13.2 | 29.5 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 91.6 |

| 9.5 | 3.2 | 90.1 | 100 | 100 | 90.8 | 60.0 |

| 4.75 | 0.4 | 13.5 | 98.7 | 100 | 53.2 | 34.4 |

| 2.36 | 0.4 | 2.6 | 72.3 | 100 | 26.4 | 18.2 |

| 1.18 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 53.0 | 100 | 17.4 | 13.9 |

| 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 32.6 | 100 | 11.6 | 9.2 |

| 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 18.7 | 100 | 8.0 | 7.6 |

| 0.15 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 11.8 | 100 | 6.4 | 6.2 |

| 0.075 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 3.8 | 90.6 | 4.7 | 5.0 |

| Sieve Mesh (mm) | 26.5 | 19.0 | 16.0 | 13.2 | 9.5 | 4.75 | 2.36 | 1.18 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.15 | 0.075 |

| Aggregate passing rate | 100 | 90 | 78 | 62 | 50 | 26 | 16 | 12 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ||

| 100 | 92 | 80 | 72 | 52 | 44 | 33 | 24 | 17 | 13 | 7 |

| Aggregate | 10–20 mm | 5–10 mm | 0–5 mm | Filler | 0–10 mm RAP | 10–20 mm RAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20% RAP | 35 | 14 | 27 | 4 | 10 | 10 |

| 30% RAP | 32 | 11 | 23 | 4 | 15 | 15 |

| 40% RAP | 28 | 8 | 20 | 4 | 20 | 20 |

| 50% RAP | 28 | 5 | 13 | 4 | 25 | 25 |

| Test Group | Amount of RAP (%) | Amount of Rejuvenating Agent (%) | Mixing Temperature (°C) | Mixing Time (s) | Mixing Orders | Thickness of Asphalt Film (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 | 3 | 120 | 90 | Order 1 | 6 |

| 2 | 30 | 5 | 140 | 180 | Order 2 | 7 |

| 3 | 40 | 7 | 160 | 270 | Order 3 | 8 |

| 4 | 50 | 9 | 180 | 360 | Order 4 | 9 |

| Dependent Variable: Degree of Blending | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Type III SS | DF | MS | F | P | ηp2 |

| Calibration model | 2388.369 a | 22 | 108.562 | 5.721 | 0.019 | 0.954 |

| Intercept | 308.414 | 1 | 308.414 | 16.253 | 0.007 | 0.730 |

| Particle size | 59.103 | 3 | 19.701 | 1.038 | 0.045 | 0.342 |

| Amount of RAP | 501.688 | 3 | 167.229 | 8.813 | 0.441 | 0.815 |

| Amount of rejuvenating agent | 475.414 | 3 | 158.471 | 8.351 | 0.013 | 0.807 |

| Mixing temperature | 535.624 | 3 | 178.541 | 9.409 | 0.015 | 0.825 |

| Mixing time | 330.04 | 3 | 110.013 | 5.798 | 0.011 | 0.744 |

| Mixing order | 457.861 | 3 | 152.62 | 8.043 | 0.033 | 0.801 |

| Asphalt content | 361.744 | 4 | 90.436 | 4.766 | 0.016 | 0.761 |

| Error | 113.854 | 6 | 18.976 | — | — | — |

| Grand total | 120,179.055 | 29 | — | — | — | — |

| Total correction | 2502.223 | 28 | — | — | — | — |

| Influencing Factor | Trends in Influencing Factors | Trends in the Degree of Blending | Ranking of Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amount of RAP | Increase | Enhance | 6 |

| Amount of rejuvenating agent | Increase | Enhance | 2 |

| Mixing temperature | Increase | Enhance | 3 |

| Mixing time | Increase | Enhance | 1 |

| Mixing orders | RAP + virgin aggregate + Virgin asphalt | Enhance | 5 |

| Asphalt content | Increase | Enhance | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zou, H.; Sui, Y.; Lu, W.; Wang, T.; Guo, D.; Sun, X.; Liu, Z. Quantitative Evaluation of the Blending Between Virgin and Aged Aggregates in Hot-Mix Recycled Asphalt Mixtures. Materials 2025, 18, 5439. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235439

Zou H, Sui Y, Lu W, Wang T, Guo D, Sun X, Liu Z. Quantitative Evaluation of the Blending Between Virgin and Aged Aggregates in Hot-Mix Recycled Asphalt Mixtures. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5439. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235439

Chicago/Turabian StyleZou, Haoyang, Yunlong Sui, Wei Lu, Teng Wang, Dedong Guo, Xupeng Sun, and Zhiye Liu. 2025. "Quantitative Evaluation of the Blending Between Virgin and Aged Aggregates in Hot-Mix Recycled Asphalt Mixtures" Materials 18, no. 23: 5439. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235439

APA StyleZou, H., Sui, Y., Lu, W., Wang, T., Guo, D., Sun, X., & Liu, Z. (2025). Quantitative Evaluation of the Blending Between Virgin and Aged Aggregates in Hot-Mix Recycled Asphalt Mixtures. Materials, 18(23), 5439. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235439