We focus on systems subjected to sudden loading, with load values representing both subcritical and critical regimes. This approach makes it possible to systematically analyse the temporal evolution of the number of crushed pillars, providing detailed insight into the dynamics of successive bursts of failures in both regimes. In particular, it allows us to capture differences in failure progression and load redistribution mechanisms that emerge under distinct load transfer rules.

3.1. Strength of the System

In analysing the simulation results, we begin with the system strength

. It is well established that under the GLS rule, the mean system strength asymptotically converges to a finite, non-zero value [

10,

34,

35]. For large systems (

), with strength thresholds

uniformly distributed on the interval

, the mean strength is given by

In the case where the strength thresholds follow a Weibull distribution, the corresponding quantity reads [

36]

The GLS rule represents a mean-field approximation. Within the global load-sharing framework, the system strength, together with the associated critical load, is independent of the specific loading protocol.

In contrast, when the LLS rule is employed, the results differ significantly. Systems subjected to sudden loading under the LLS rule exhibit lower values of

and

compared to those obtained under quasi-static loading conditions. Generally, it is known that

[

11,

28]. The mean strength of LLS systems under sudden loading is well approximated by the following size-dependent formula [

19,

37]

where

and

are fitting parameters. The values of these parameters, obtained from our simulations for different system disorders, are summarised in

Table 1. A pronounced size effect is evident in LLS systems: the mean strength,

, decreases monotonically toward zero as

N keep growing.

Table 1 also reports the root mean square error (RMSE) as an indicator of fit quality. The consistently low RMSE values across all distributions of pillar strength thresholds confirm the accuracy of the fits. These supplementary statistics for the LLS systems are included both to validate the reliability of the estimated values and to provide a reference point for comparison with the results of our Voronoi-based model.

It turns out that the size-effect in the VLS rule is correctly approximated by the following formula:

This formula extends Equation (

4), which properly describes LLS systems, by introducing the factor,

, thus incorporating an additional parameter. The fitted values of the parameters

,

and

, together with the measure of the fit (RMSE), are presented in

Table 1. The values of the coefficients

and

are not the same for the VLS and LLS rules. This indicates that results generated by the VLS rule cannot be obtained by multiplying those obtained under the LLS rule by a simple multiplication by the factor

.

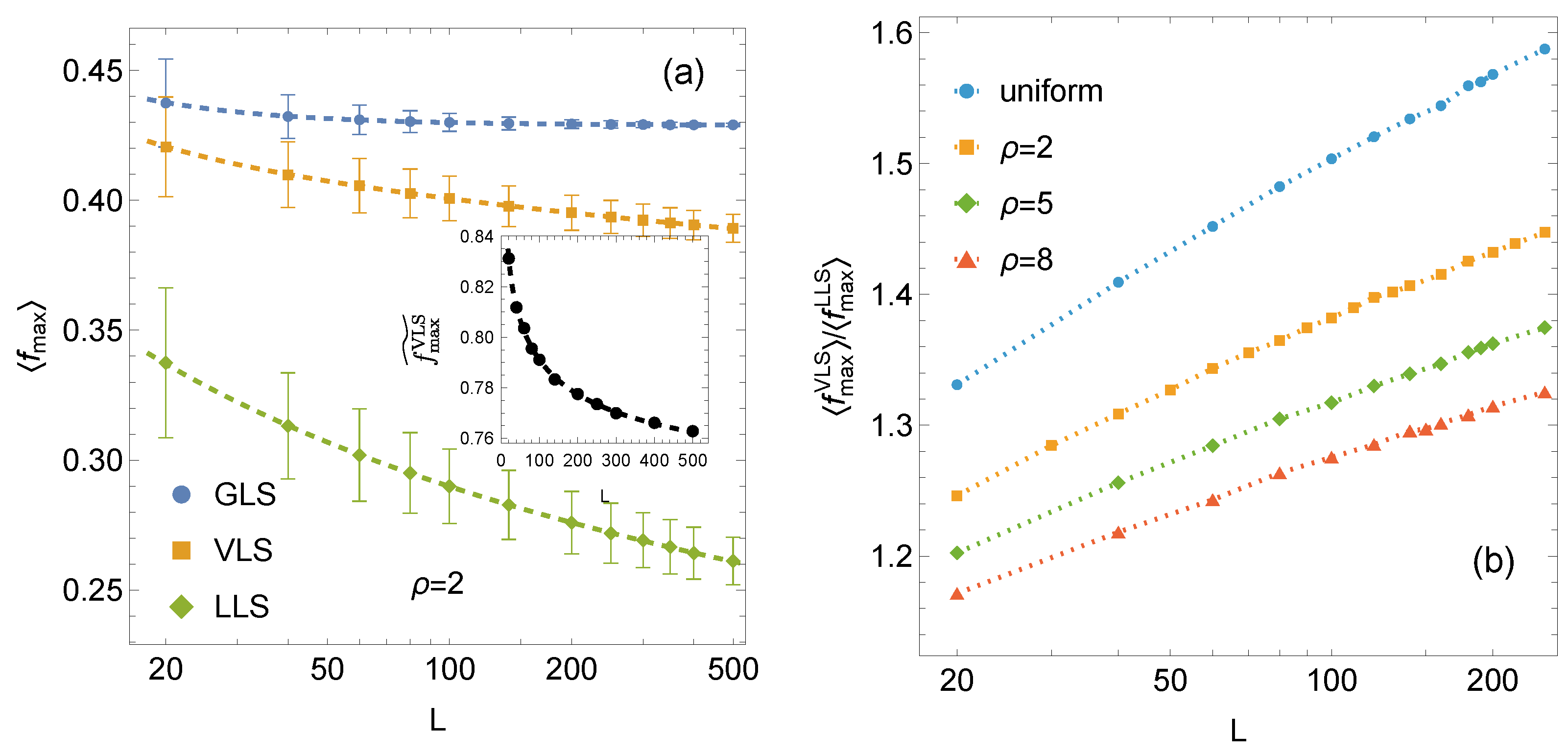

A graphical comparison of the mean system strength under the GLS, VLS, and LLS rules is shown in

Figure 2. The VLS curve lies between the two limiting cases. The

curve decreases monotonically toward zero, similarly to the LLS case, but at a considerably slower rate. Within the examined range of system sizes, the VLS results remain closer to the GLS curve, yet their asymptotic trend clearly differs from that of GLS, which does not decay to zero. Therefore, it is instructive to examine the relative strength of the VLS systems which we define as

As shown in the inset in

Figure 2, the relative strength

decreases with increasing system size signalising that VLS systems gradually approach the behavior of LLS systems as

N grows. At the same time, the ratio

increases with system size (see

Figure 2b). These trends together indicate that, although VLS systems exhibit a size effect, it is significantly weaker than that observed for LLS systems.

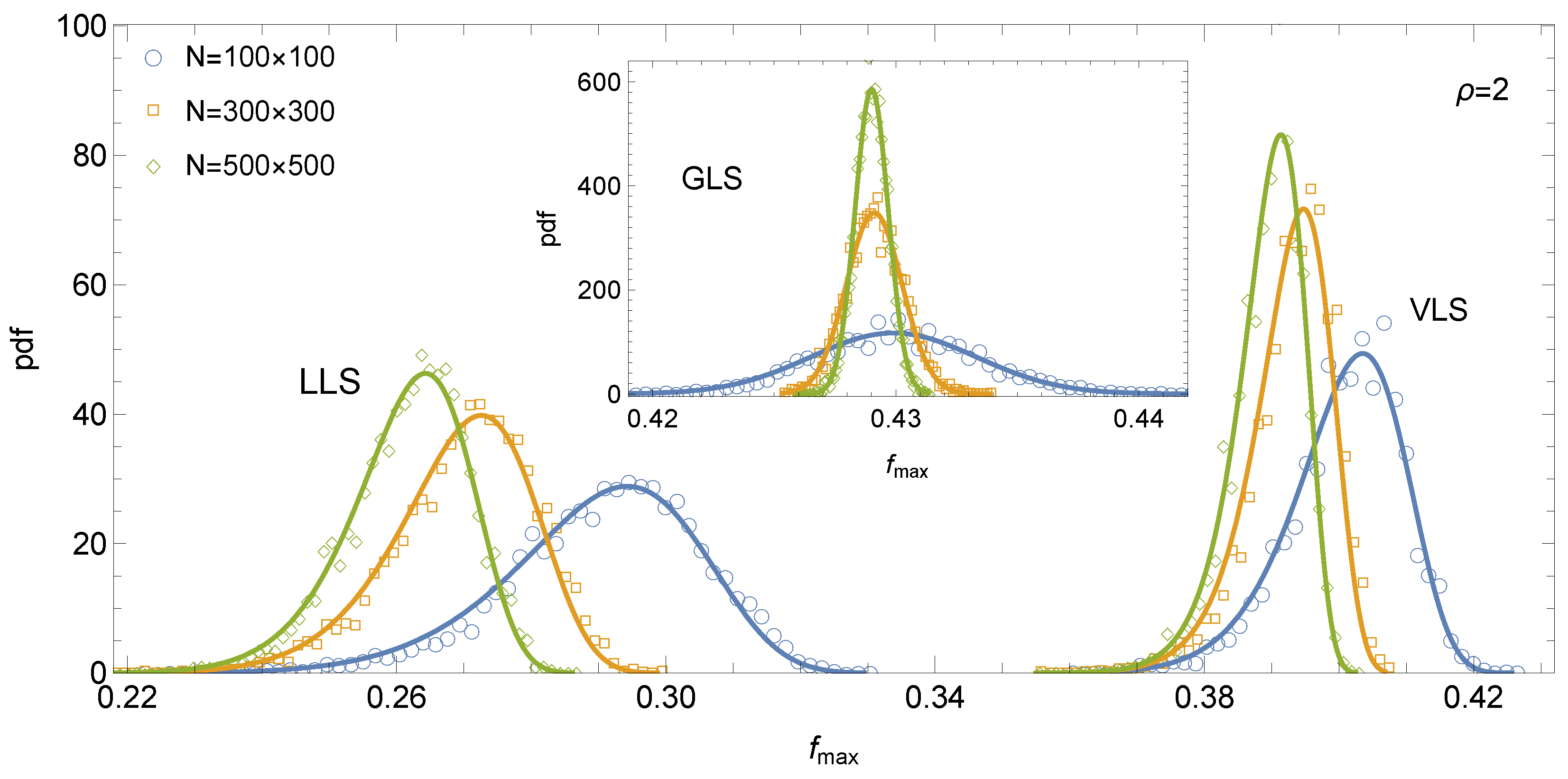

Analysis of the empirical distributions of system strength reveals clear distinctions among the three load-sharing rules. For GLS systems, the distribution of

is symmetric and well approximated by a Gaussian law (see inset in

Figure 3). In contrast, LLS systems display a moderately left-skewed distribution, which is accurately described by the three-parameter Weibull distribution (see

Figure 3). The VLS rule exhibits a qualitatively similar trend to LLS, as the distribution of

is also negatively skewed. Interestingly, the skewness in VLS systems, particularly for larger

N, tends to exceed that observed in LLS systems, although it generally remains within the range of moderate skewness. Consequently, the distribution of

—similarly to that of

—is modelled using the three-parameter Weibull distribution (see

Figure 3)

where

are the shape, scale, and location parameters, respectively.

It is worth emphasising that selecting an appropriate distribution for the collected data is a crucial step. Several established methods are available for constructing confidence intervals and performing hypothesis tests, including the universal framework [

38]. With this in mind, the data sets were thoroughly examined using appropriate goodness-of-fit tests, through which we identified

, seen in Equation (

7), as the distribution that most accurately represents the empirical distributions of

. It should be noted, however, that a substantial portion of the data can also be satisfactorily described by the three-parameter skew-normal probability distribution. Nevertheless, we chose to represent all data using Equation (

7) because the Weibull distribution provides an adequate fit for nearly all data sets and, in cases where both models are acceptable, yields higher maximised likelihood values and greater

p-values than the skew-normal model.

A comparison of the corresponding probability density functions highlights a pronounced size effect in VLS systems: with increasing system size, the pdf shifts leftwards while its peak grows, reflecting decreasing mean strength and reduced dispersion. This trend closely resembles the behaviour observed in LLS systems. In contrast, GLS systems display virtually no size effect in terms of mean strength, exhibiting only a reduction in dispersion with increasing system size.

3.2. Fraction of Pillars Failing Under Subcritical Load

When a subcritical load is applied to an array of N pillars, a certain fraction of pillars fails. Let denote the fraction of intact pillars that remain capable of sustaining the load . The complementary fraction therefore represents the proportion of crushed pillars. An important question is how scales with system size N, that is, how large the fraction of failed pillars can become while the system remains marginally stable under the applied load.

For GLS systems, there exists an analytical solution to this question. Specifically, the fraction of failed pillars under

asymptotically converges to a nonzero value in the limit

:

for systems with Weibull-distributed strength thresholds, whereas for systems with uniformly distributed thresholds

the corresponding asymptotic value is

The quantity can be interpreted as a subcritical fraction, as it represents the largest proportion of pillars that may fail without triggering global failure when the applied load remains below the critical load . In this sense, characterises the maximum extent of local failure that the array can tolerate under sudden loading while still preserving overall stability.

Based on the simulation results, we find that the mean subcritical fraction

for both LLS and VLS systems is accurately captured by the empirical relation

where the parameters

,

, and

are determined by fitting the expression to the numerical data. The corresponding parameter estimates for LLS and VLS systems are summarised in

Table 2.

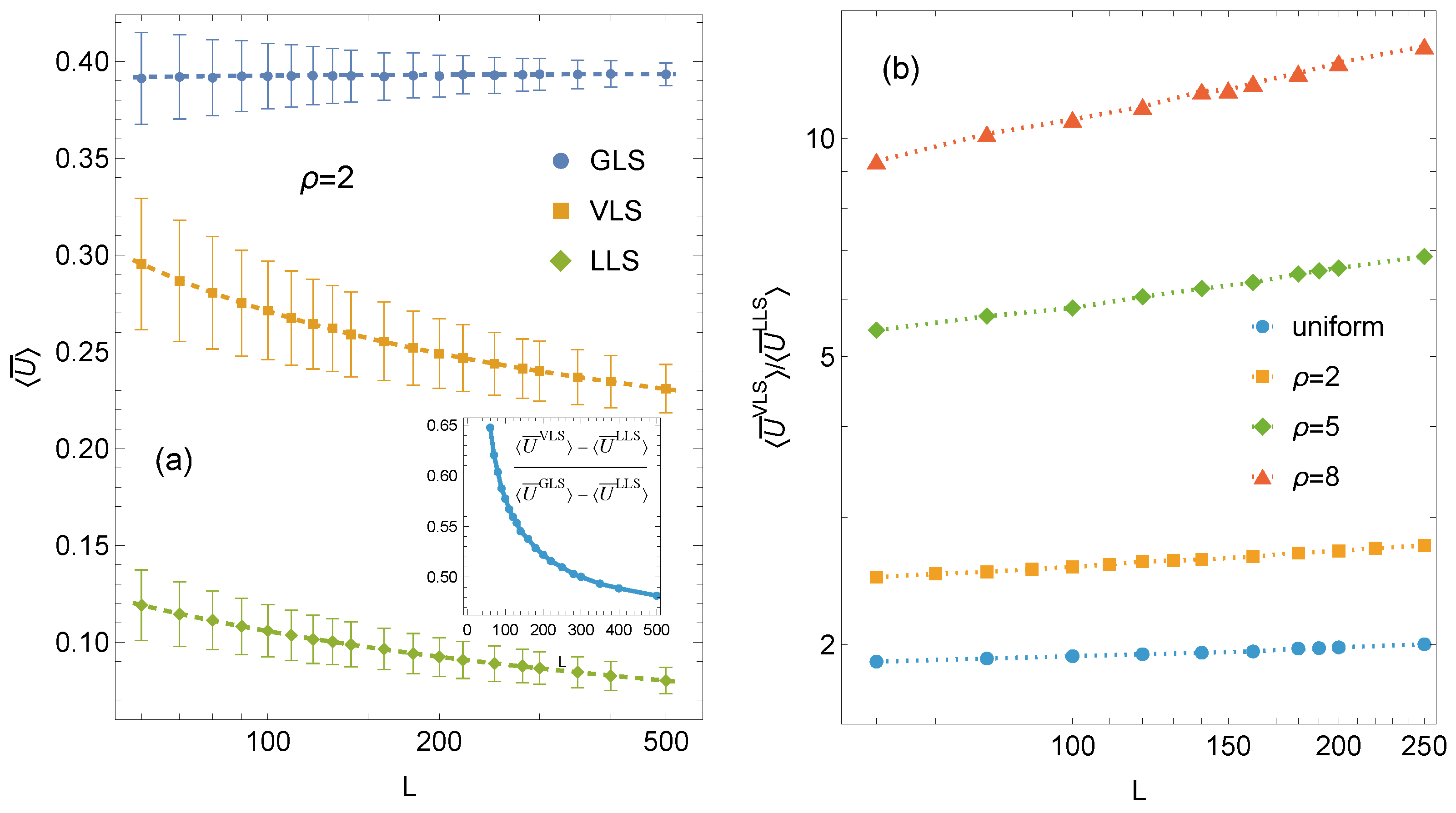

The dependence of the mean subcritical fraction of failed pillars on system size for GLS, VLS, and LLS systems is presented in

Figure 4a. Analysis of the fitted curves reveals that the VLS rule represents an intermediate load-sharing scheme, although its trend closely follows that of the LLS system. Both curves decrease monotonically with increasing system size

N. In contrast, GLS systems display virtually no size effect—the mean subcritical fraction increases only slightly, reflecting the diminishing statistical fluctuations that accompany larger

N. In absolute terms, the mean subcritical fraction in VLS systems decreases more rapidly than in LLS systems, and the behaviour of VLS systems gradually converges toward that of LLS systems as

N increases (see inset in

Figure 4a). However, when relative values are considered, the LLS curve decays faster than the VLS curve, as shown in

Figure 4b, which presents the ratio

. This ratio increases with system size and becomes larger for weaker disorder. The latter observation reflects the tendency of LLS systems to exhibit increasingly brittle behaviour as disorder decreases. In the ideal brittle limit, any local failure triggers a self-sustaining cascade of bursts leading to complete system collapse, and consequently

under

.

The corresponding mean subcritical fractions of failed pillars are summarised in

Table 3. Owing to its perfectly homogeneous load redistribution, the GLS rule allows the largest fraction of failed pillars, resulting in the smallest proportion of surviving ones and the highest maximum load

among the three schemes. Conversely, LLS systems sustain the lowest

and exhibit the smallest subcritical fraction. The VLS rule, as expected, lies between those two limiting cases. Although the load redistribution in VLS systems is not uniform, the subcritical fraction of failed pillars remains significantly higher than in LLS systems across all analyzed sizes. This contrast becomes particularly pronounced in weakly disordered systems (

and

), where LLS systems become close to the brittle limit (

), whereas VLS systems maintain values several times higher. For

, in particular, the LLS response is nearly perfectly brittle, allowing only isolated failures under

, while the corresponding VLS values exceed them by more than an order of magnitude (see

Figure 4b).

3.3. Relaxation Time and Evolution of the Number of Failed Pillars

The loading process evolves through a sequence of failure bursts that occur between the initially intact configuration and the final stable configuration attained after loading. The total number of these bursts defines the relaxation time

, as introduced in

Section 2.5. Consequently, the sequence of bursts provides the distribution of failure sizes, representing the number of pillars that fail at each successive step.

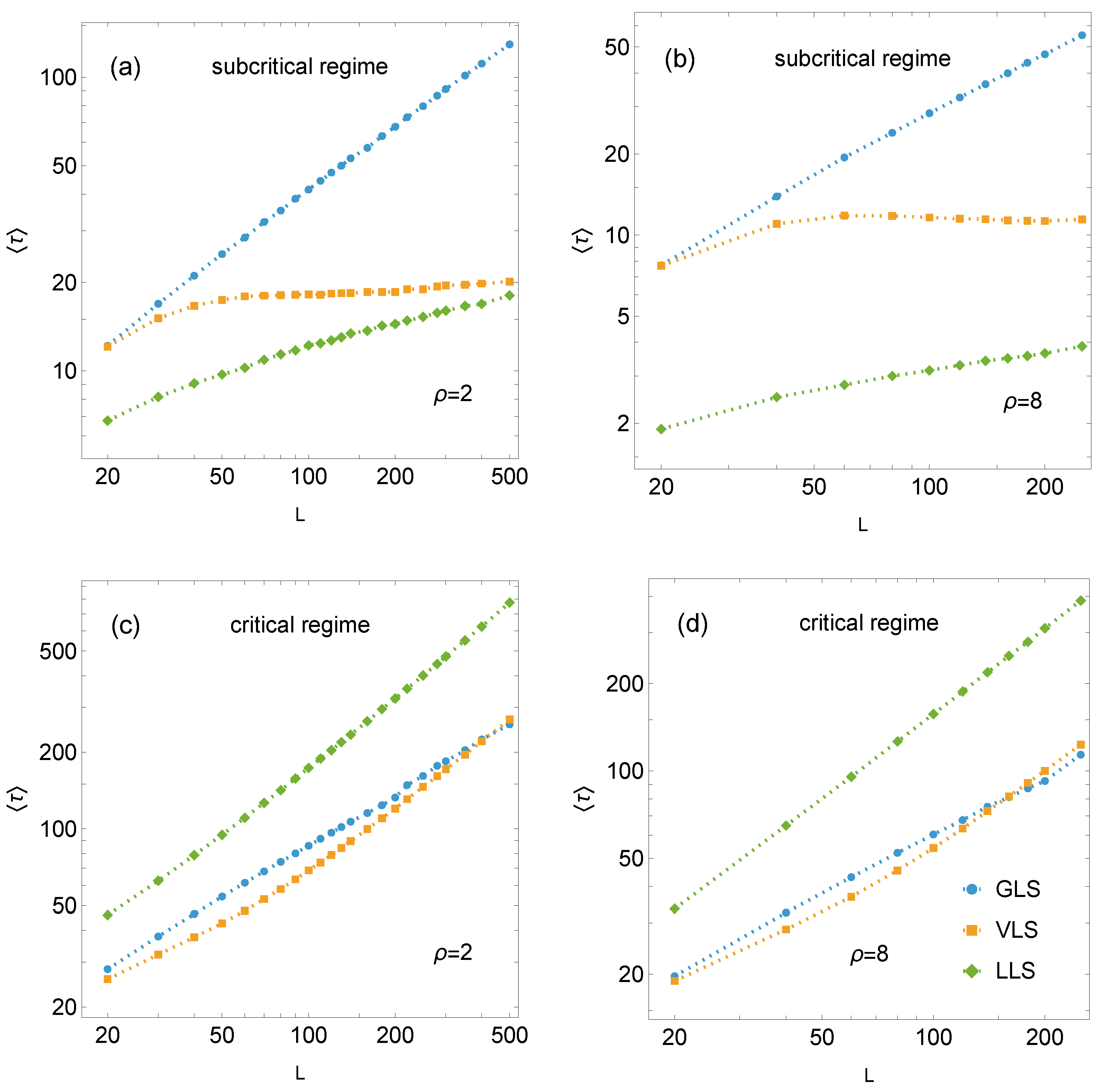

Figure 5 presents the mean relaxation times as a function of the linear system size

L for systems subjected to the subcritical load

(panels (a) and (b)) and the critical load

(panels (c) and (d)).

In the subcritical regime, the relaxation time of GLS systems is longer than that for the VLS and LLS systems, reflecting a greater number of bursts before reaching a stable configuration of partial failure. Within the analysed range of system sizes, the damage process is shortest in LLS systems, while the relaxation time for VLS systems lies between the two extremes. The mean relaxation time increases with system size for both GLS and LLS systems, although this growth is noticeably slower for the latter. The VLS rule exhibits a distinct pattern: for and uniform disorder, the mean relaxation time rises more slowly than in the local case, whereas for and , it becomes almost insensitive to system size. Consequently, for small to moderately large system sizes, the mean relaxation time of VLS systems resembles that of GLS systems and gradually approaches that of LLS systems as the system size increases.

A different pattern emerges in the critical regime (

Figure 5c,d). Here, LLS systems display markedly longer mean relaxation times than those observed for VLS and GLS systems. Interestingly, for most system sizes (except the largest), the critical failure process in VLS systems terminates in fewer bursts than in the GLS case. However, beyond a certain size – depending on the strength-threshold distribution –

grows faster than

, and for the largest simulated systems, the GLS rule yields the shortest relaxation time.

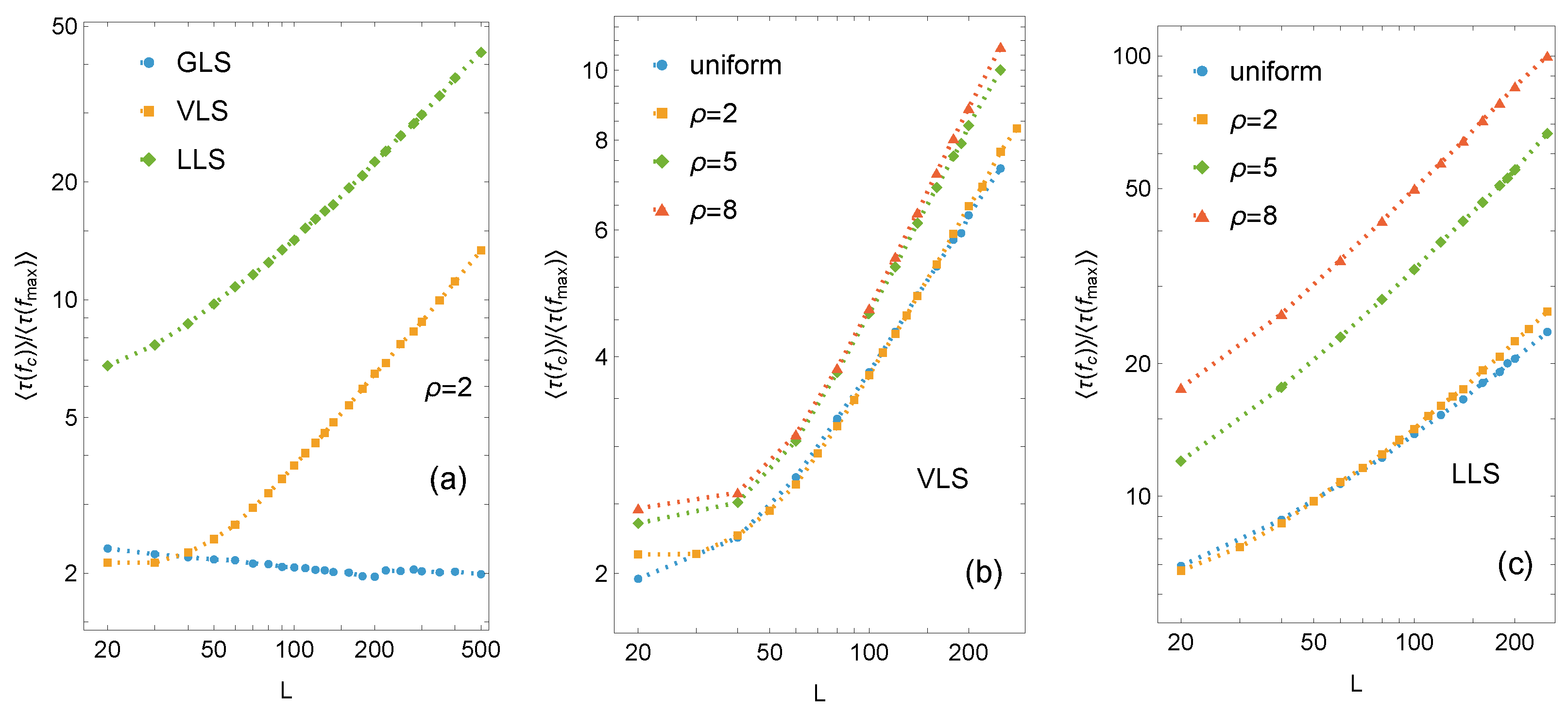

The ratio

is shown in

Figure 6. For GLS systems, this ratio remains approximately 2, with only minor statistical fluctuations across all strength distributions. Thus, the mean relaxation time under subcritical loading is roughly half that under the critical load. In contrast, a pronounced size effect is observed for LLS systems, where the ratio

increases rapidly with system size and clearly depends on the type of disorder (

Figure 6c). Voronoi-based systems also show dependence on system size and disorder, though both effects are far less pronounced than in LLS systems (

Figure 6b). Hence, the VLS behavior is clearly distinct from the global scheme but tends toward LLS dynamics while remaining less localised.

A closer look at LLS systems reveals a sharp contrast between their subcritical (

) and critical (

) responses. Under

, they rapidly reach a stable configuration (short relaxation time) with a low subcritical fraction

of failed pillars (see

Table 3). However, under the critical load

, which exceeds

only by a small increment

, all pillars fail in a prolonged, self-sustaining catastrophic avalanche of bursts. Thus, the critical load

represents a bifurcation point at which the system transitions from a stable, partially failed configuration with residual load-bearing capacity to one of complete global failure.

Even though VLS systems exhibit size effects similar to those observed in LLS systems, the transition at the bifurcation point is less pronounced. This behaviour results from two factors: (i) the subcritical fraction is considerably larger than in LLS systems, and (ii) the associated catastrophic avalanche is noticeably shorter, as it develops over a substantially smaller number of bursts.

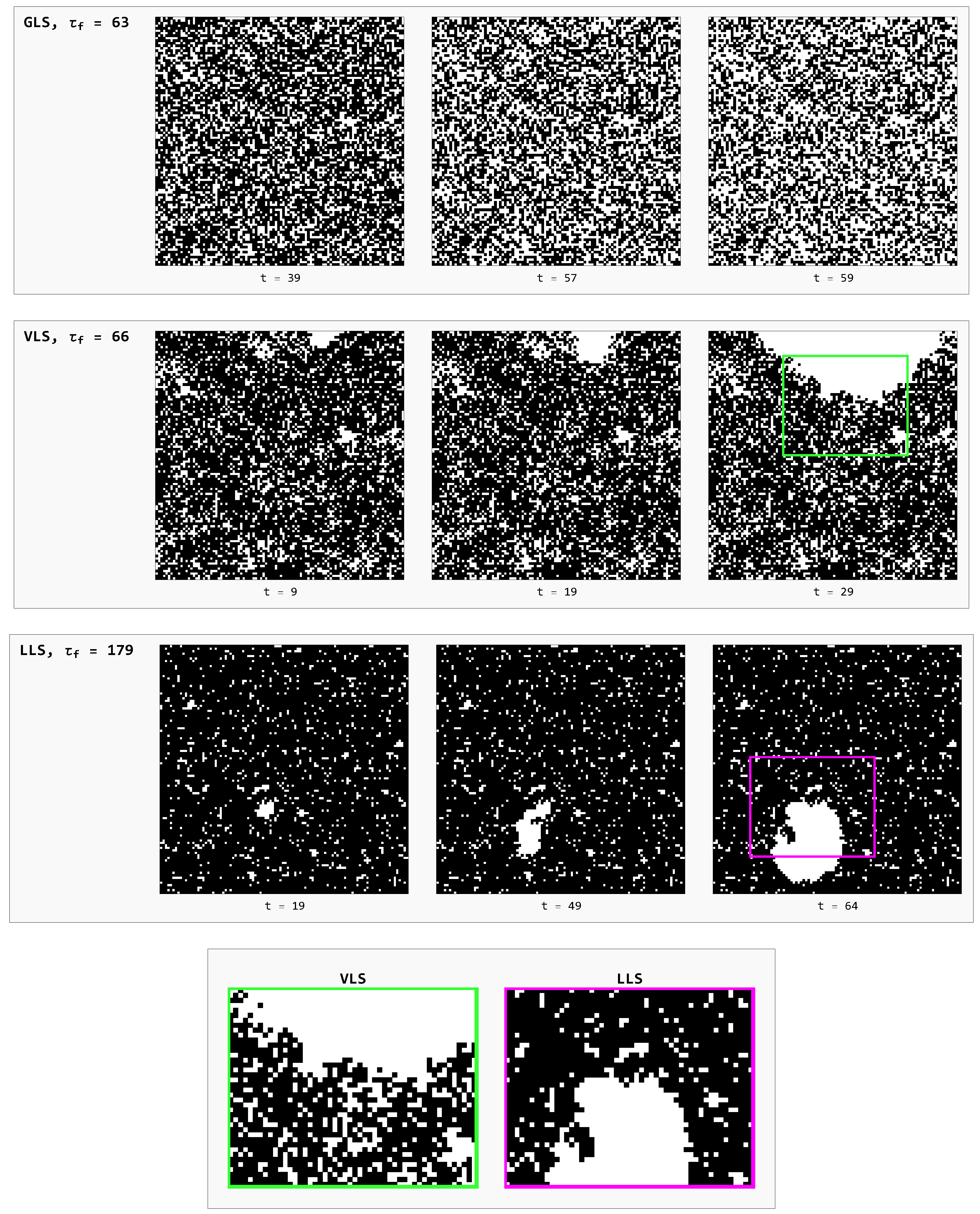

It is instructive to directly examine the spatio-temporal evolution of the failure process under critical loading for all considered load-sharing rules. This approach allows us to visualise how pillar crushing propagates through the array, as the system evolves from a state of localised, individual pillar failures (microscopic failure) to global system collapse (macroscopic failure).

Figure 7 shows snapshots of representative GLS, VLS, and LLS systems at selected time steps under

.

In GLS systems, the failure process is entirely random throughout its evolution—failures of pillars occur at random locations across the array (top row in

Figure 7). In this case, both the spatial arrangement of the pillars and the system geometry are irrelevant, as the GLS rule corresponds to a perfectly rigid substrate. The density of failed elements after the first time step (not included in

Figure 7) is the highest among all models, since the largest critical load

is required to initiate the catastrophic avalanche.

Concerning the snapshot of the LLS system (third row in

Figure 7), the onset of global failure occurs at the lowest critical load

, the fraction of failed elements at the initial step is minimal, and the degree of initial damage remains low. The first failures are randomly scattered throughout the system, as only pillars with

collapse. Subsequently, due to fully localised load redistribution, further failures predominantly occur in the neighbourhoods of previously crushed pillars, forming numerous small clusters. This process quickly stabilizes, leading to the nucleation of a single dominant cluster (see the white region slightly below and to the left of the centre at

in the third row of

Figure 7), which then expands over successive time steps by incorporating smaller clusters and ultimately drives global failure. Owing to the strong spatial correlations between local failures, the destruction propagates as a coherent wave with a smooth front, reflecting the initially low density of failed pillars prior to the growth of the dominant cluster.

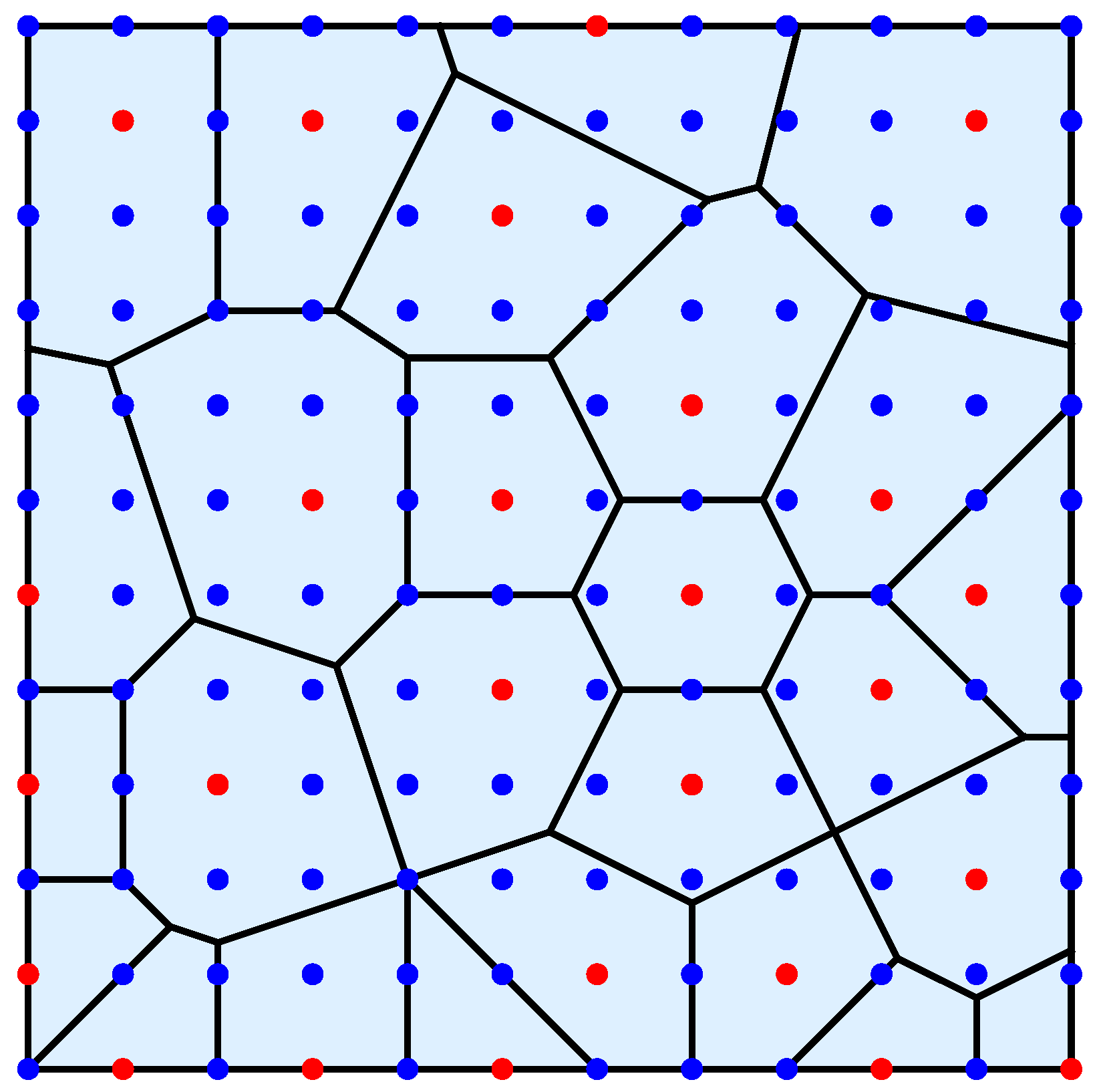

Although the spatial evolution of failures in VLS model, as seen in the second row in

Figure 7, partially resembles that of LLS systems, there are significant quantitative and qualitative differences. In particular, the catastrophic avalanche in the VLS model is triggered at a substantially higher critical load than in the LLS case. Consequently, a considerably larger fraction of pillars becomes damaged already after the initial time step, initiating a burst of secondary failures in subsequent steps. These secondary failures tend to coalesce into significantly larger clusters than those observed under the LLS rule. Similar to the LLS case, a dominant cluster eventually emerges in VLS systems; however, its formation occurs at a later stage of avalanche development. Furthermore, because load transfer in the VLS rule is less localised, failures are not confined solely to the dominant cluster. The resulting destruction front in VLS systems is therefore rough and irregular, in sharp contrast to the smooth, well-defined front characteristic of LLS systems (see bottom row of

Figure 7).

From a temporal perspective, the evolution of critically loaded VLS systems, measured in terms of relaxation time, closely resembles that of GLS systems. Taken together, the spatio-temporal characteristics reveal that the VLS rule combines features of both LLS and GLS models. In particular, critically loaded VLS systems exhibit an interplay between the critical load—substantially higher than in LLS yet lower than in GLS—and the effective range of load redistribution, which is neither fully localised nor entirely global. This interplay produces relaxation times that are significantly shorter than in LLS systems and approach those of GLS systems, despite the much higher critical load observed in the latter. The underlying reason is that failure progression in VLS systems remains cluster-like, in contrast to the cluster-free dynamics of GLS systems, where redistributed load is shared equally among all surviving pillars.

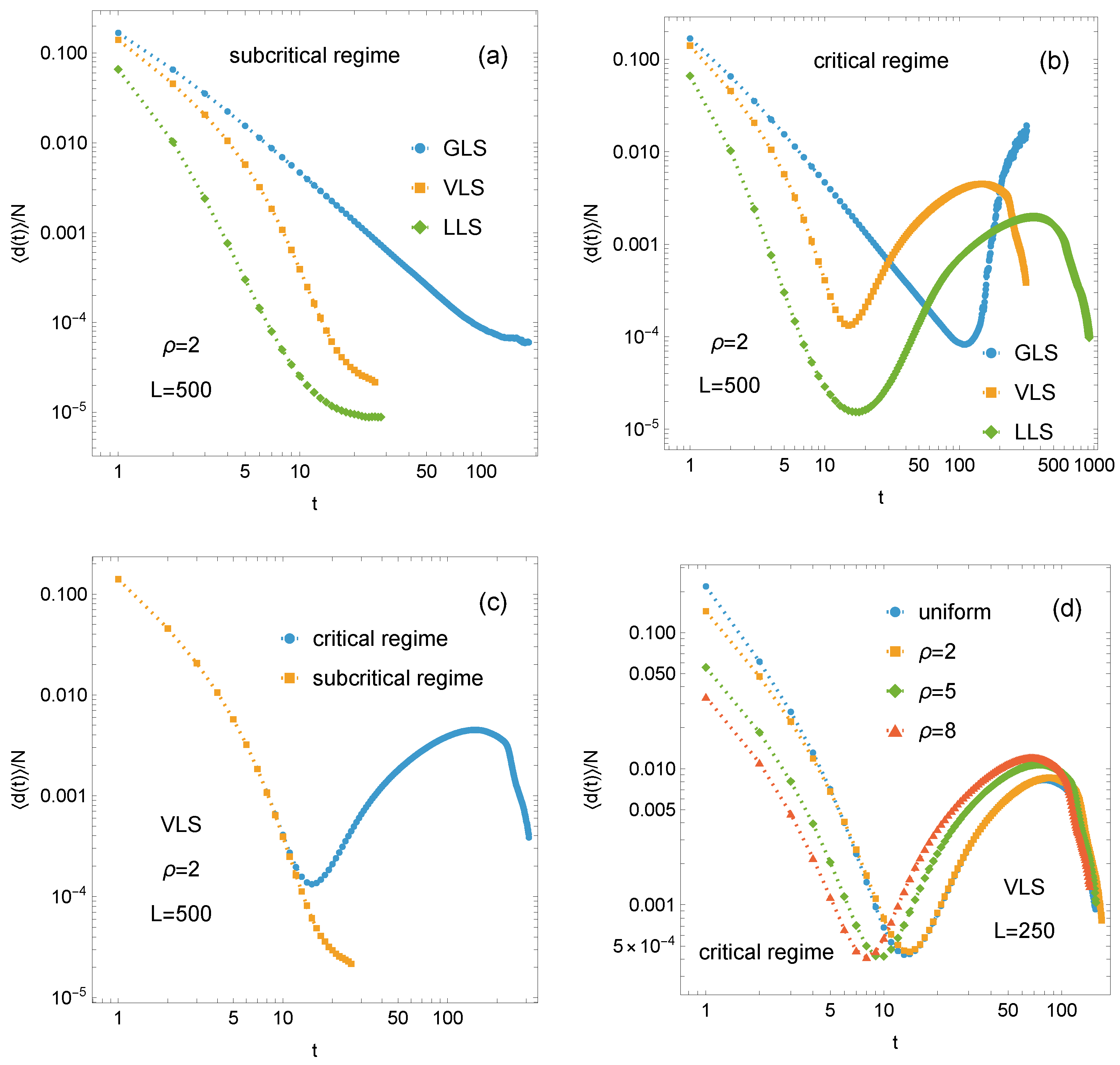

Finally, we examine the evolution of the failure process, averaged over all samples for each configuration.

Figure 8 presents the mean fraction of failed pillars at successive time steps as a function of time for both the subcritical and critical regimes. The following observations are worth noting:

(i) The results for the subcritical regime are shown in

Figure 8a. It is observed that the curves of

decrease with time

t for all load-sharing rules, with the most rapid decline occurring in the LLS systems. The mean number of failed pillars decreases monotonically, particularly in the LLS and VLS systems, until the failure process ceases. The intermediate nature of the VLS rule is clearly visible, as the corresponding

curve consistently lies between the two limiting cases represented by the GLS and LLS systems.

(ii)

Figure 8b presents the mean fraction of failed pillars at successive time steps under critical loading. Initially,

decreases for all load-sharing rules. However, unlike in the subcritical regime, the curves exhibit an upturn once a minimum is reached. For GLS systems, this upturn develops into a monotonic increase that continues until global failure occurs. In contrast, VLS and LLS systems display a distinct pattern: after reaching their global minima,

increases toward a local maximum and subsequently decreases during the final stage of failure. Despite quantitative differences, such as in relaxation times, the LLS and VLS curves exhibit qualitatively similar behaviour. Panel (c) of

Figure 8 combines the information presented in panels (a) and (b), focusing exclusively on the VLS systems.

(iii) Regardless of whether the system is in the subcritical or critical regime, the early-stage dynamics of VLS and, in particular, LLS systems are characterised by a rapid decrease in the fraction of failed pillars, with no apparent distinction between the two regimes, as shown in panels (a), (b), and (c) of

Figure 8. Divergence appears only near the minimum of the critical-regime curve: while the subcritical curve continues to fall steeply, the critical curve slows, signalling imminent system collapse. Importantly, the characteristic shape of the critical-regime VLS curve in

Figure 8b is independent of the assumed strength-threshold distribution. The same qualitative behaviour is observed for both the uniform case and for Weibull distributions with

, 5, and 8 (see

Figure 8d).