Identification of Factors Leading to Damage of Semi-Elliptical Leaf Springs

Abstract

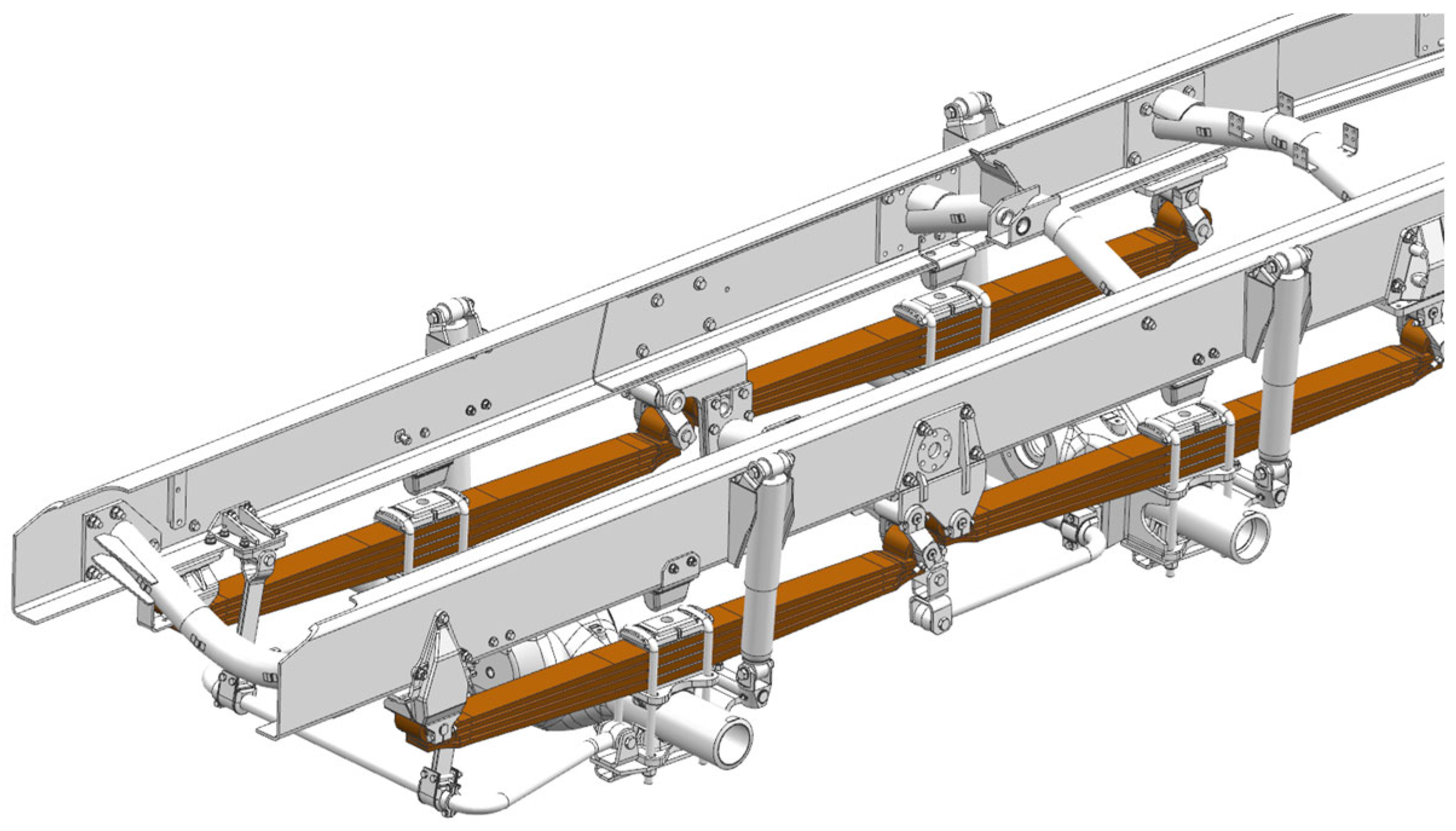

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

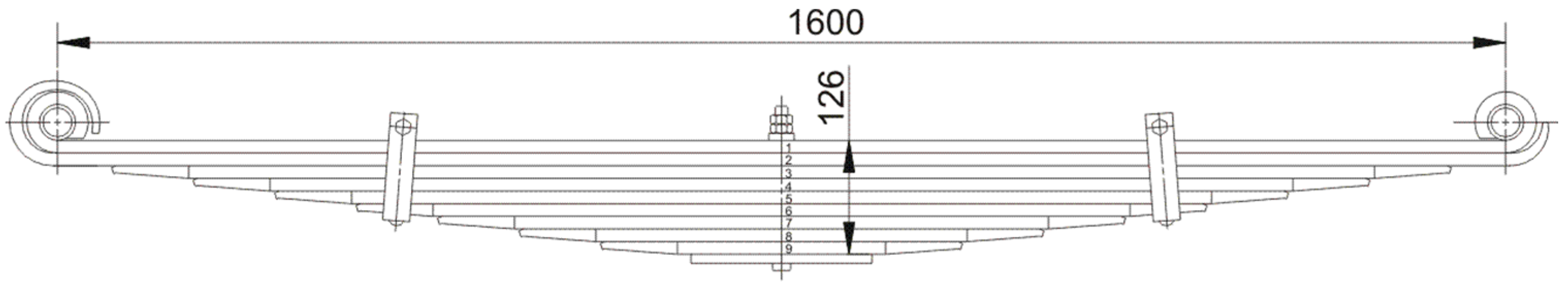

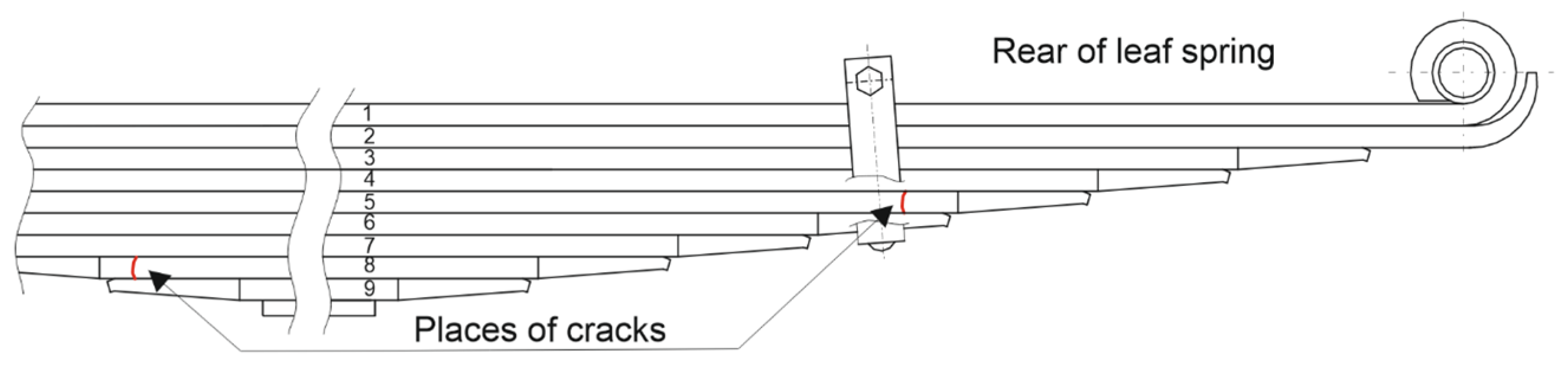

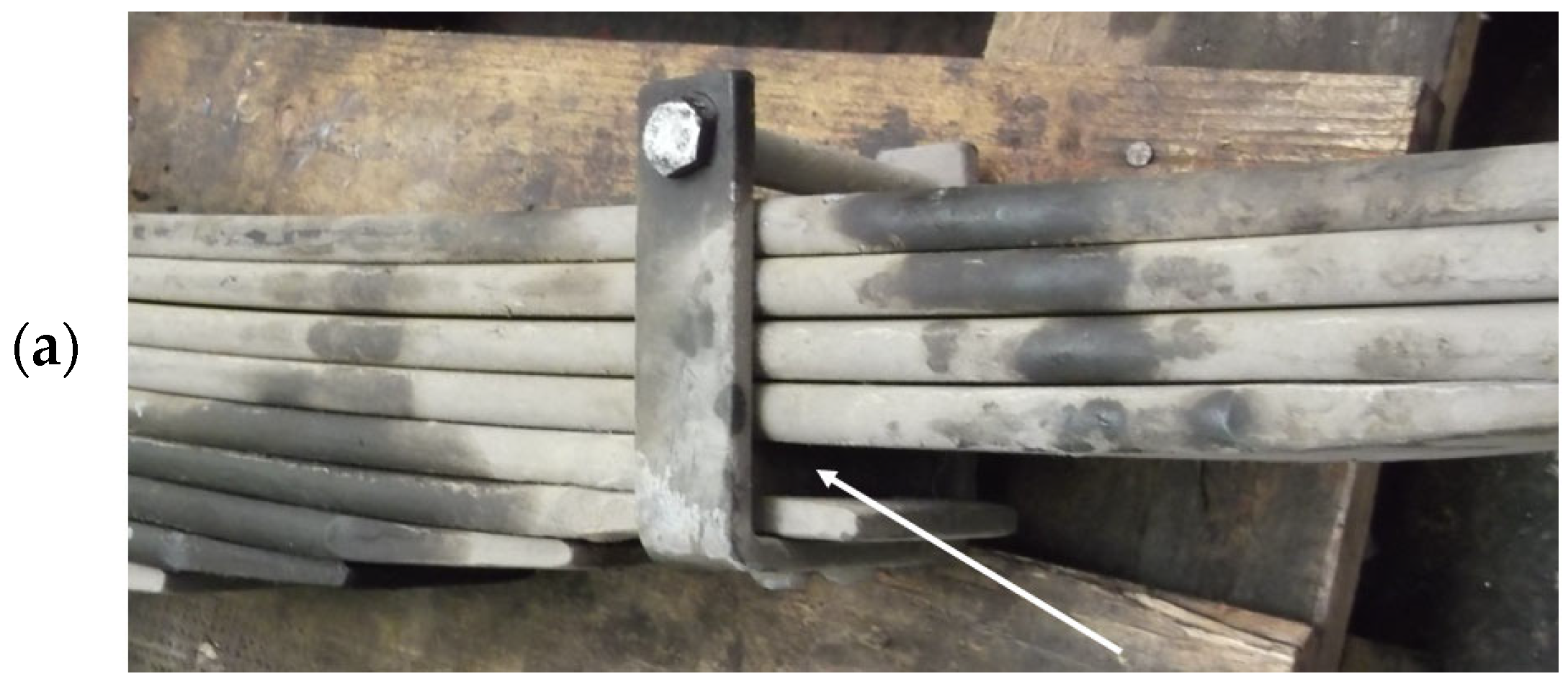

2.1. Analysis of Spring Geometry

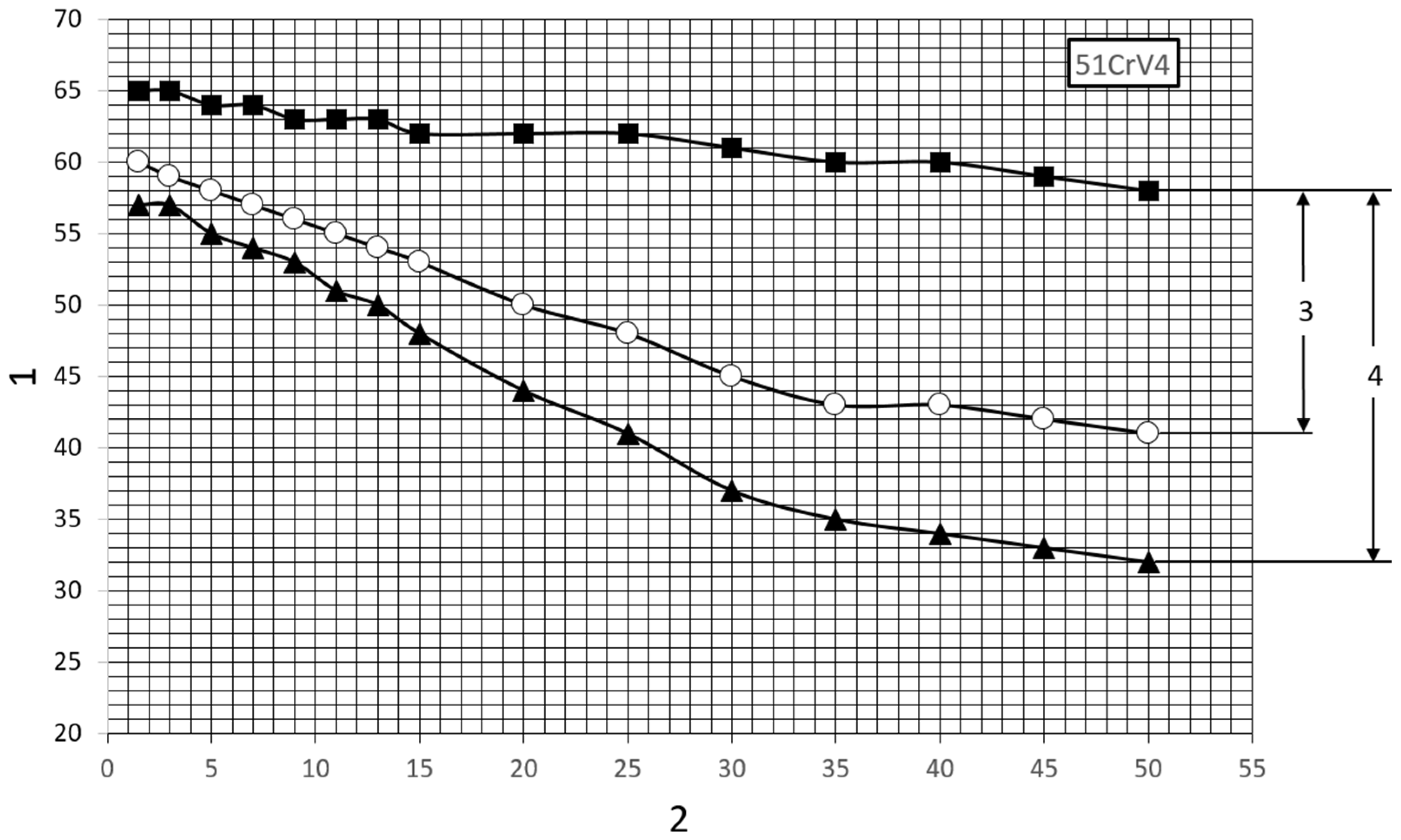

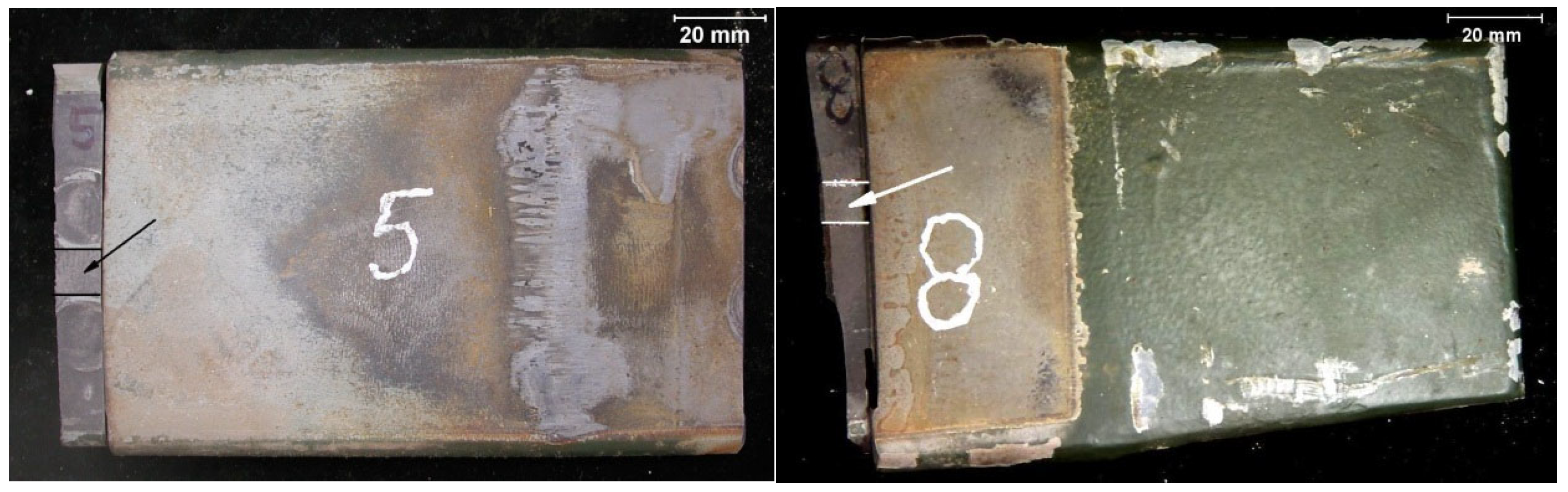

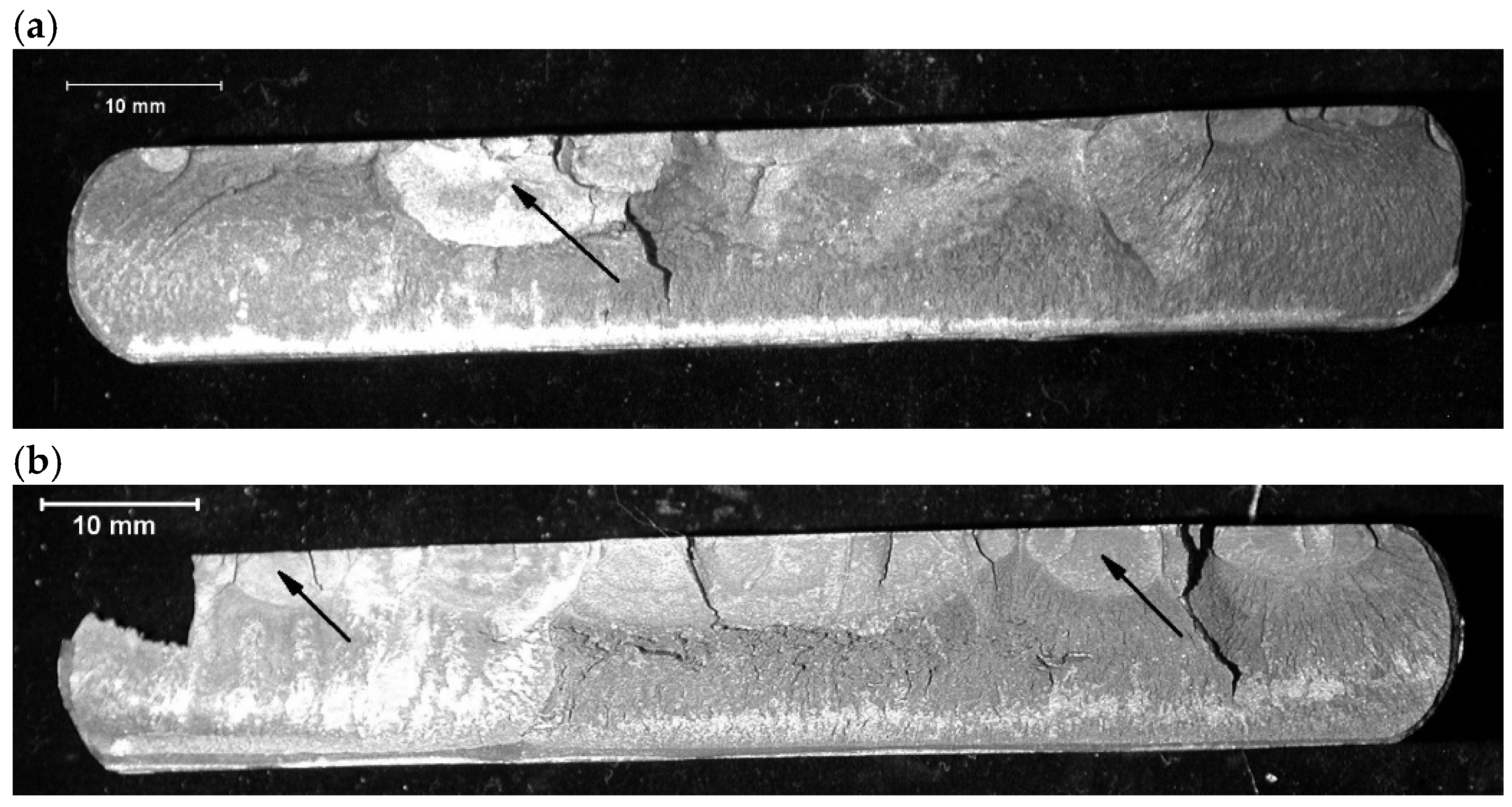

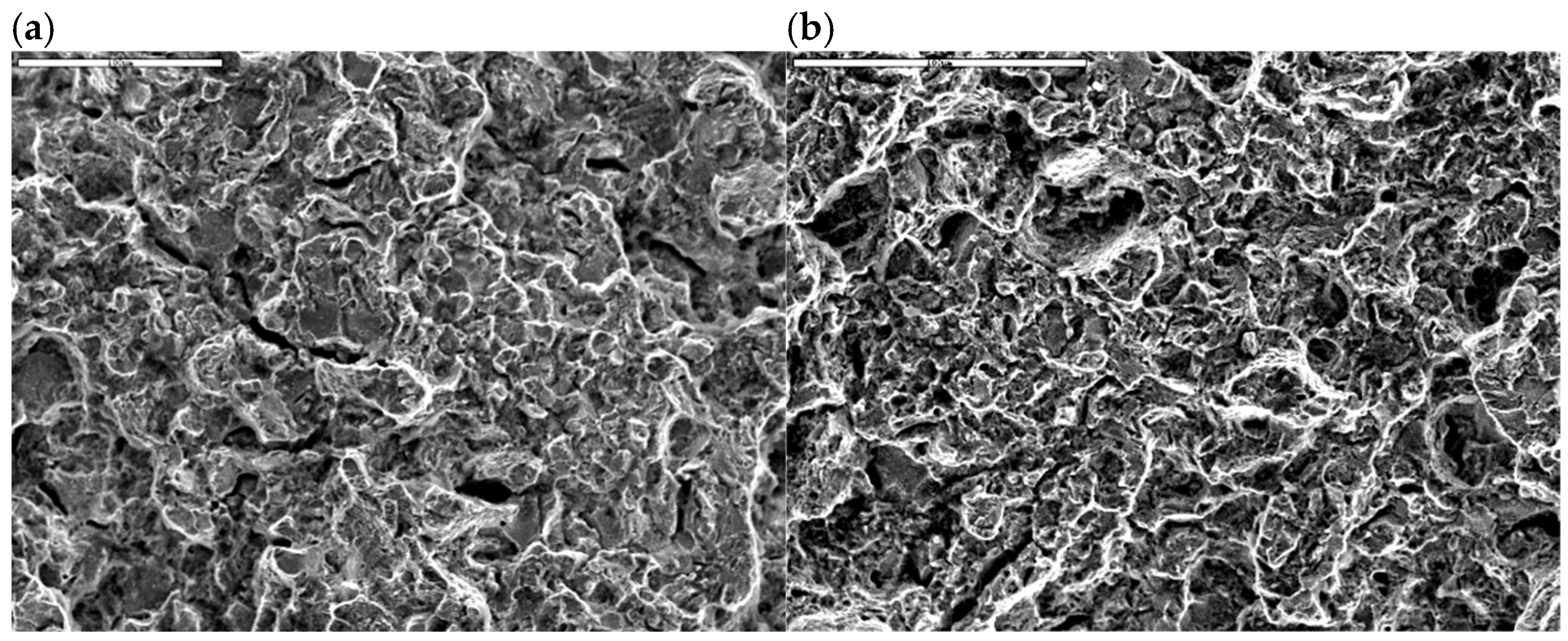

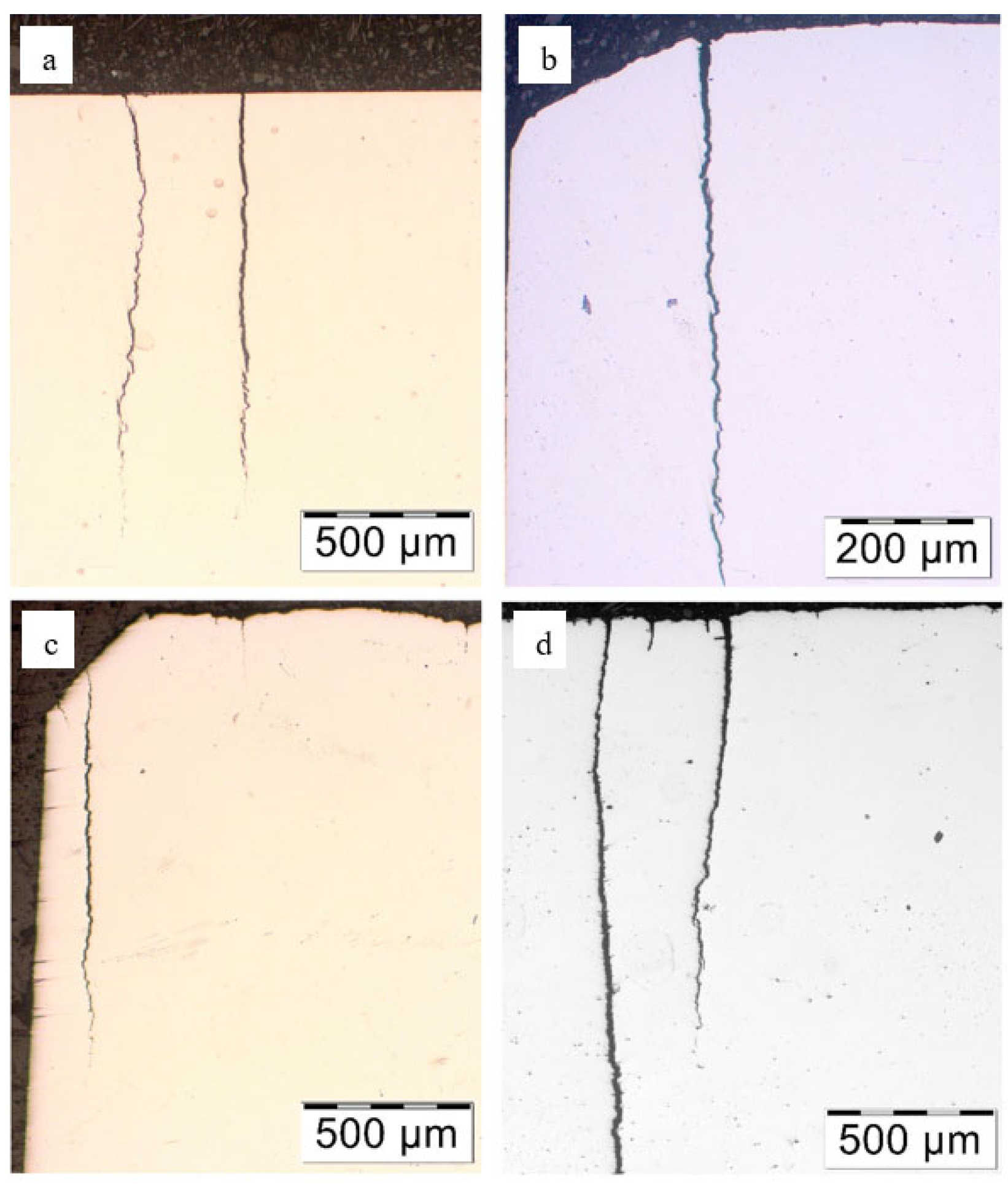

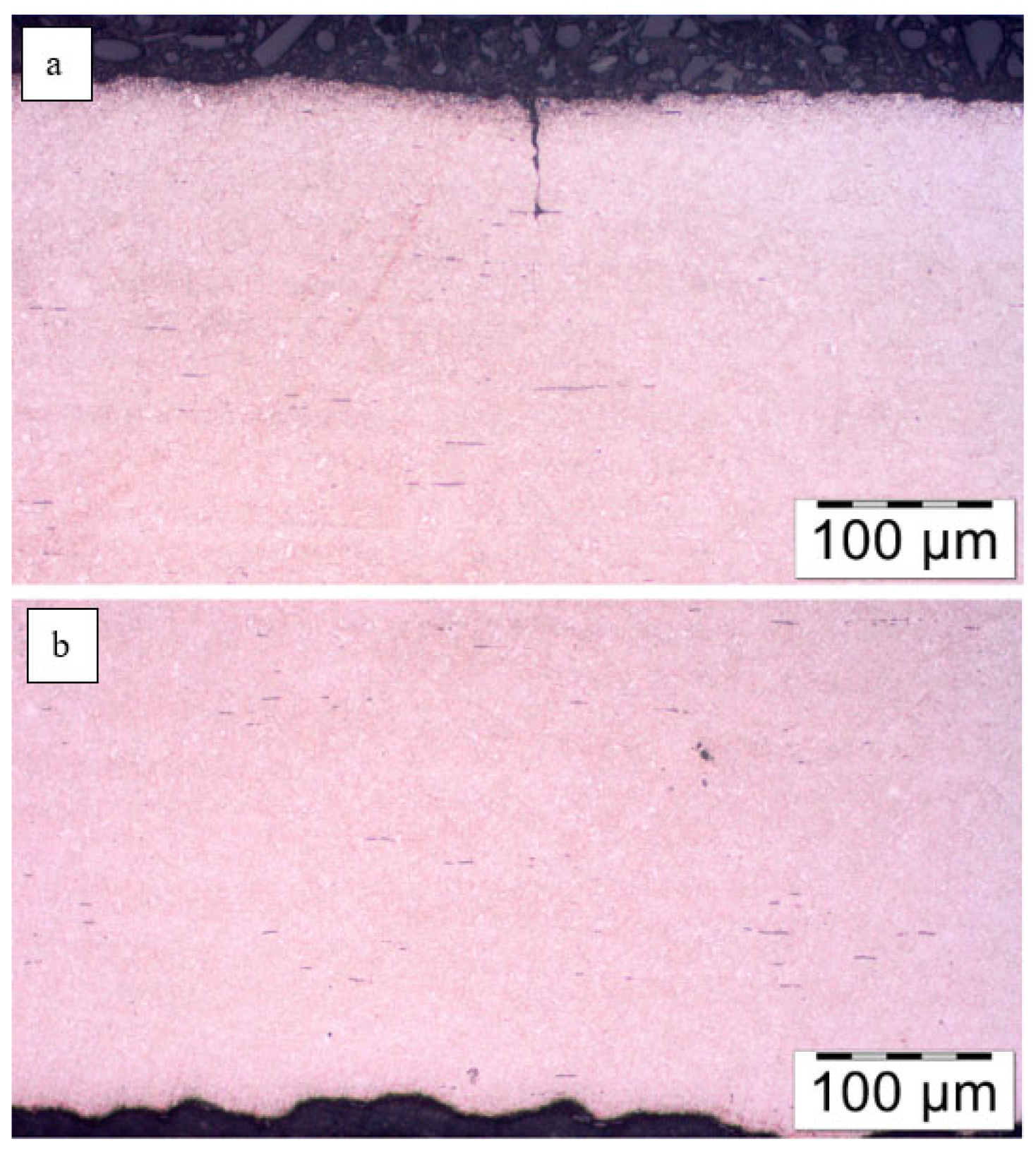

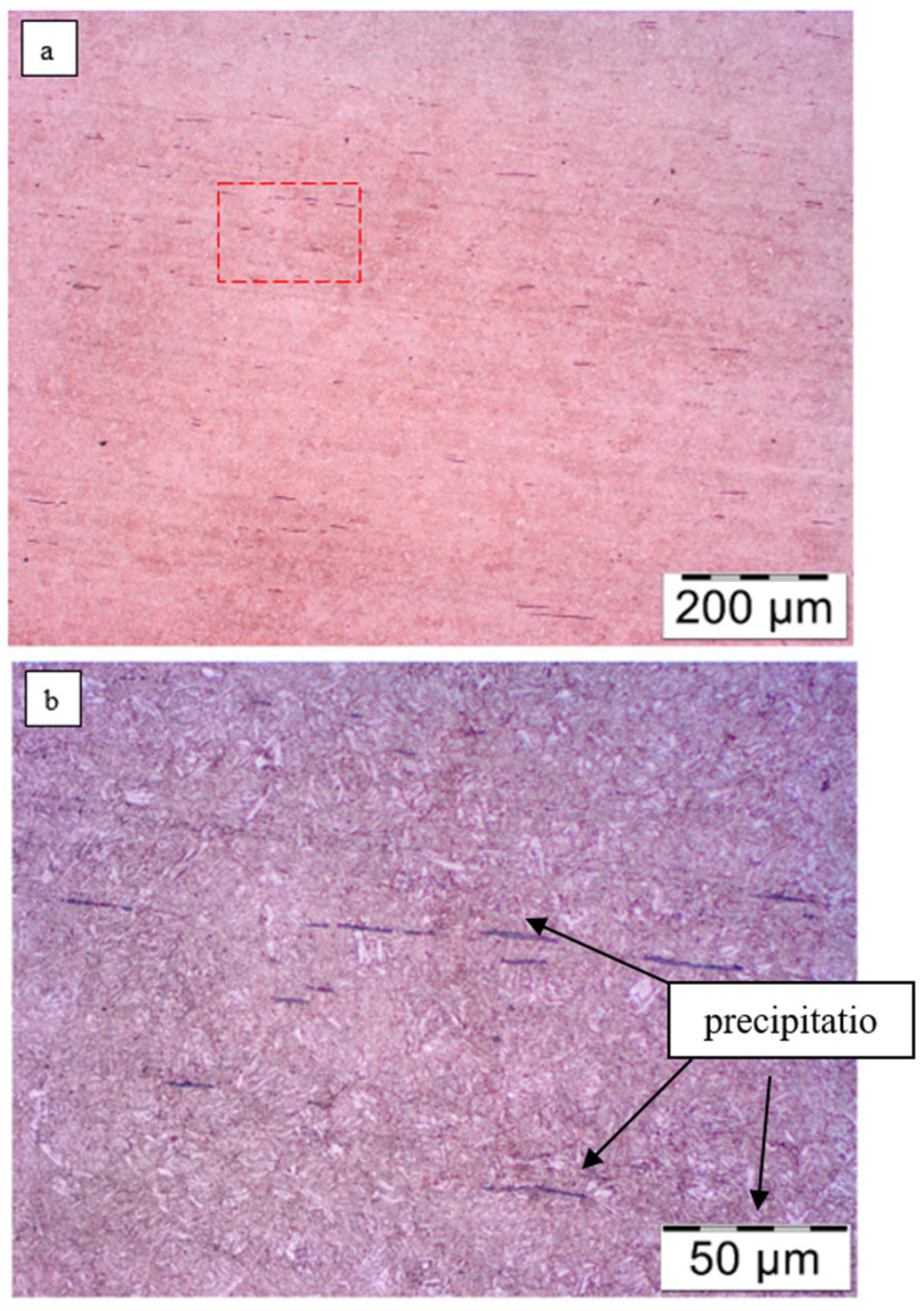

2.2. Metallographic Studies

- stereoscopic microscope: SMT-800

- scanning electron microscope: JEOL JSM 6610A equipped with an EX-230 probe

- light microscope: OLYMPUS GX51.

- The spring leaves, after shaping, should be subjected to heat treatment, which consists of hardening and tempering;

- The microstructure of spring leaves should be formed by highly tempered martensite (fine or medium needle-like), without traces of superheating, with no visible grain boundaries at ×500 magnification;

- Leaf decarburization should not exceed 0.3 mm from the surface [17].

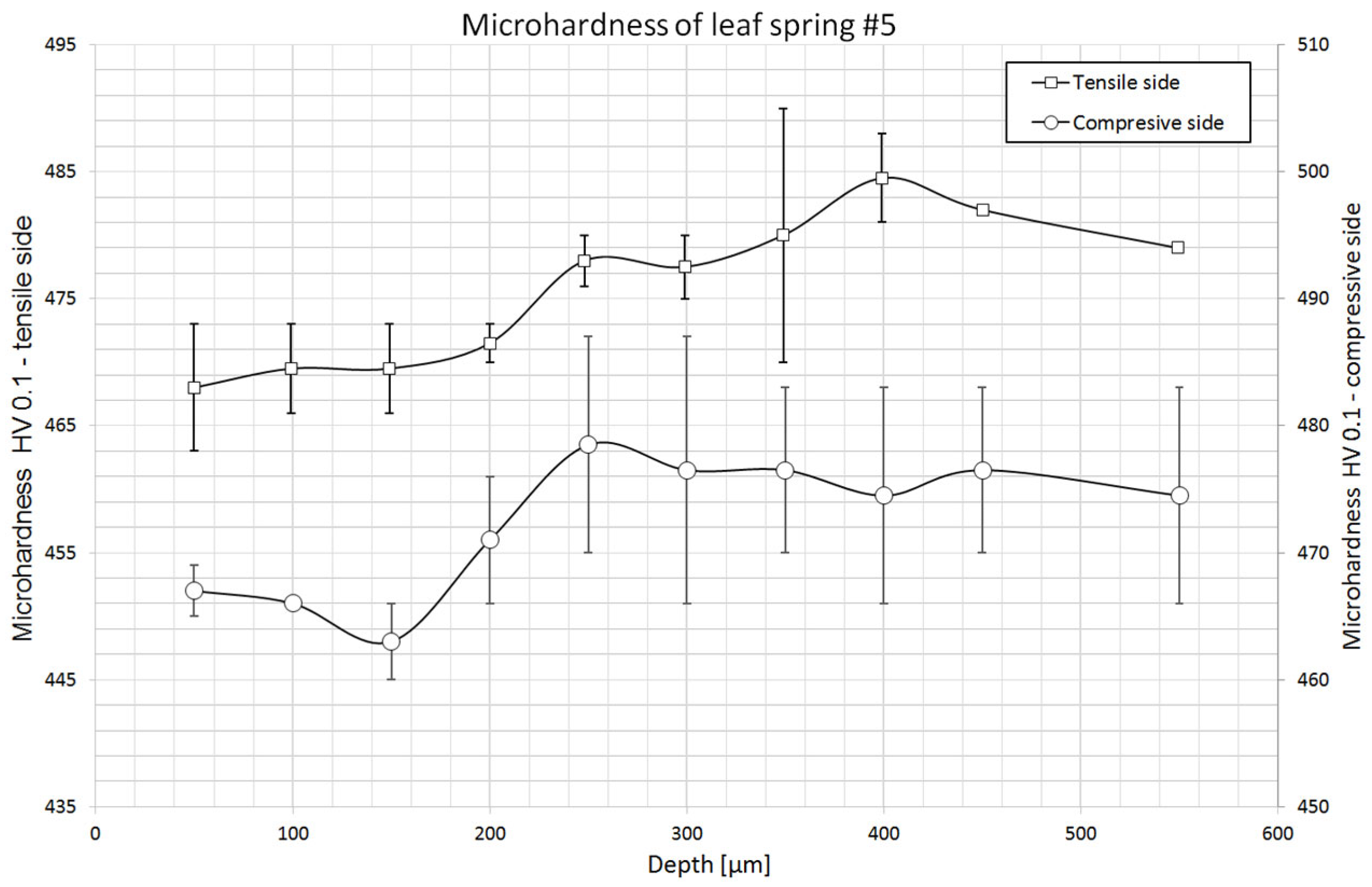

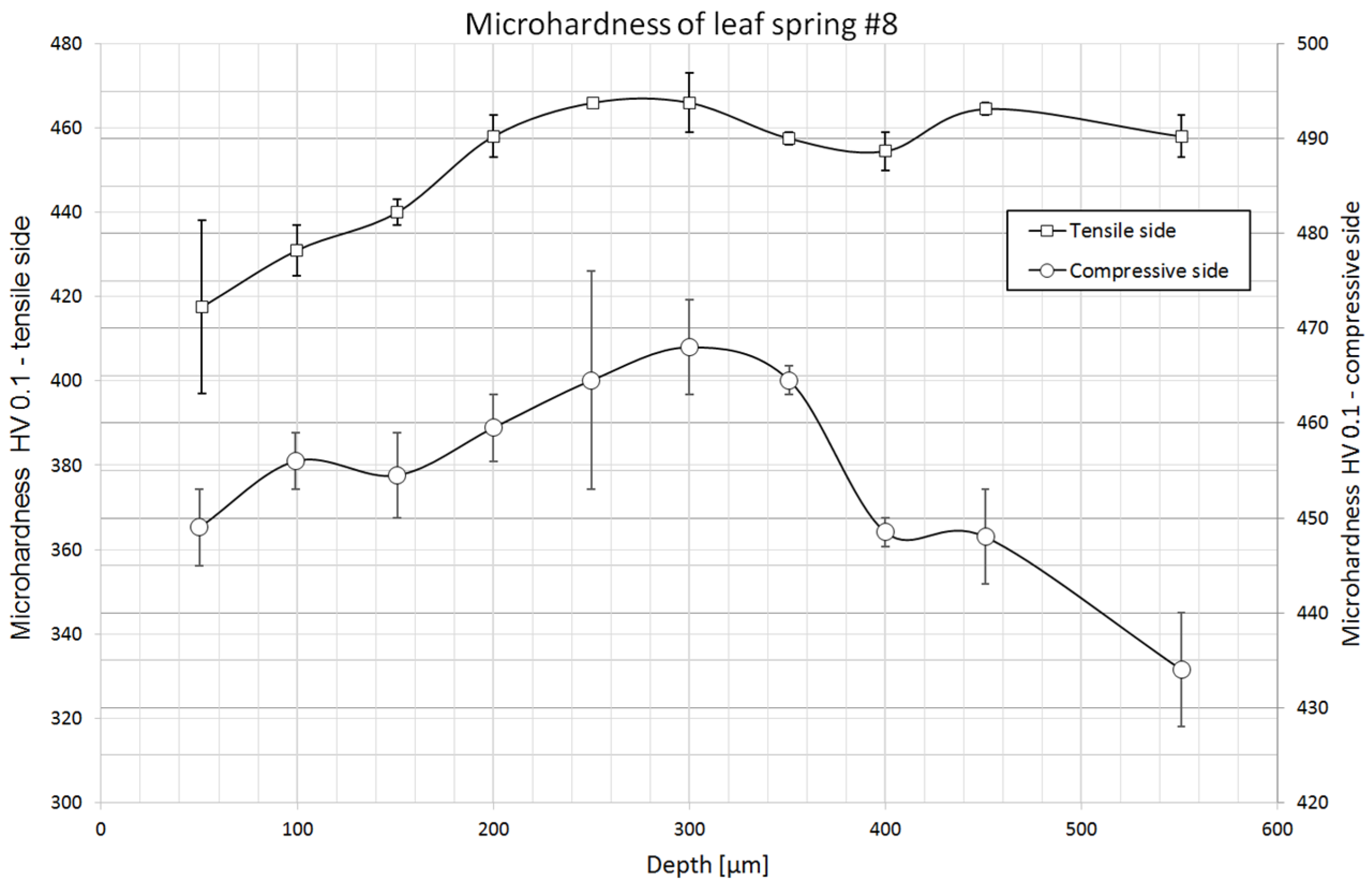

2.3. Hardness Measurements

- Summary of the Research Part

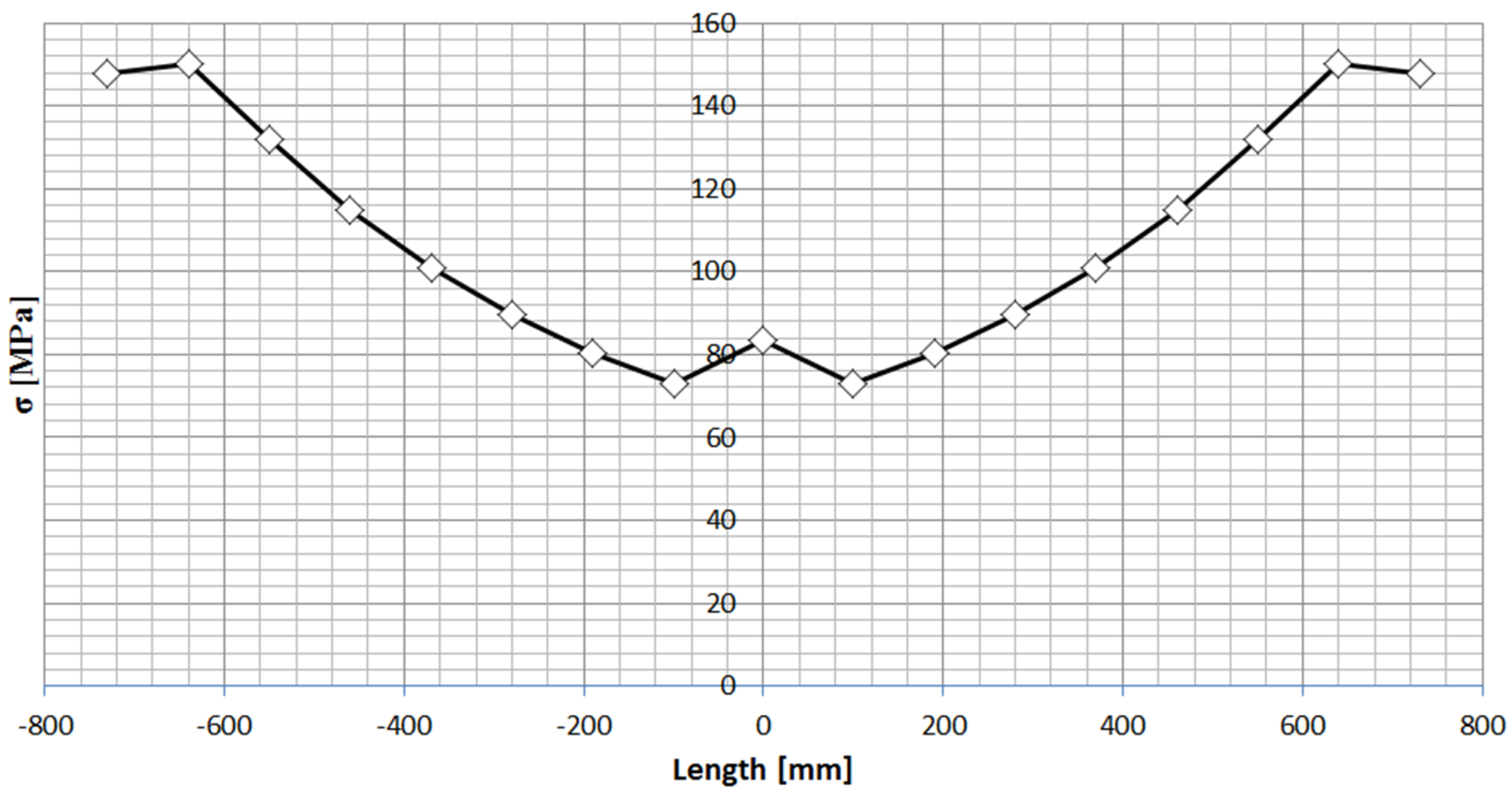

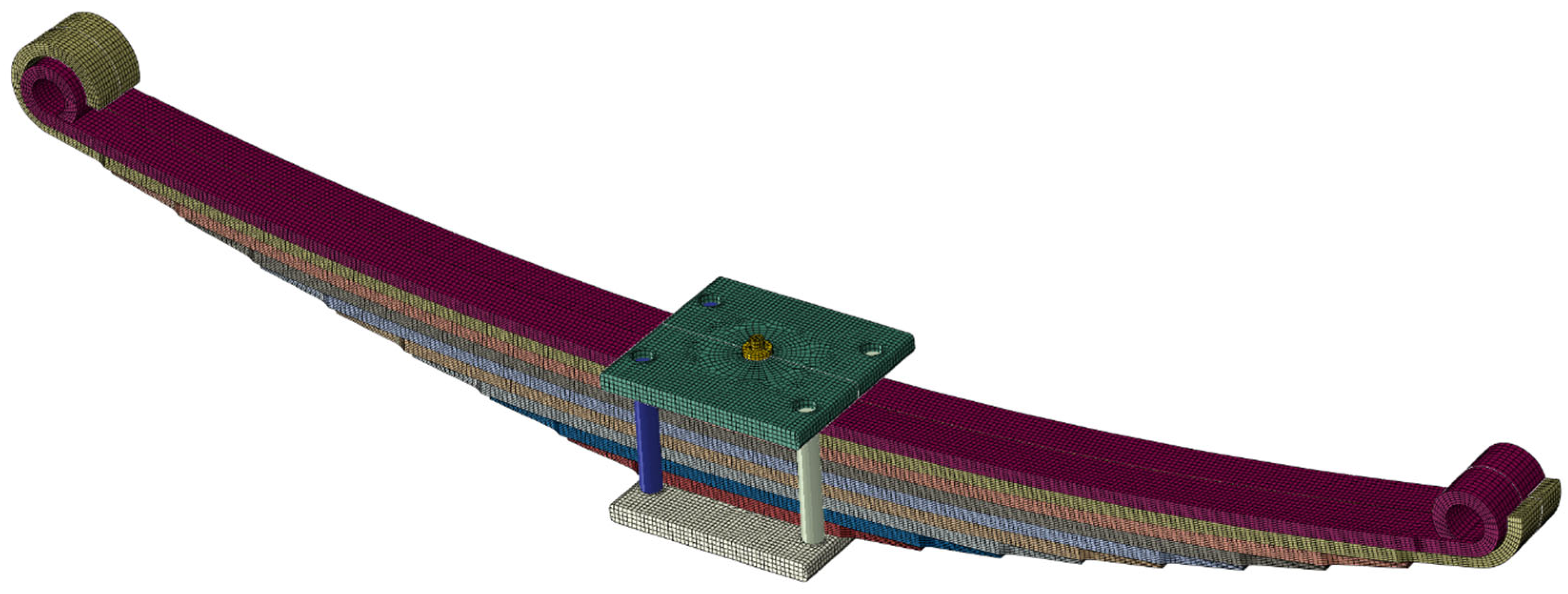

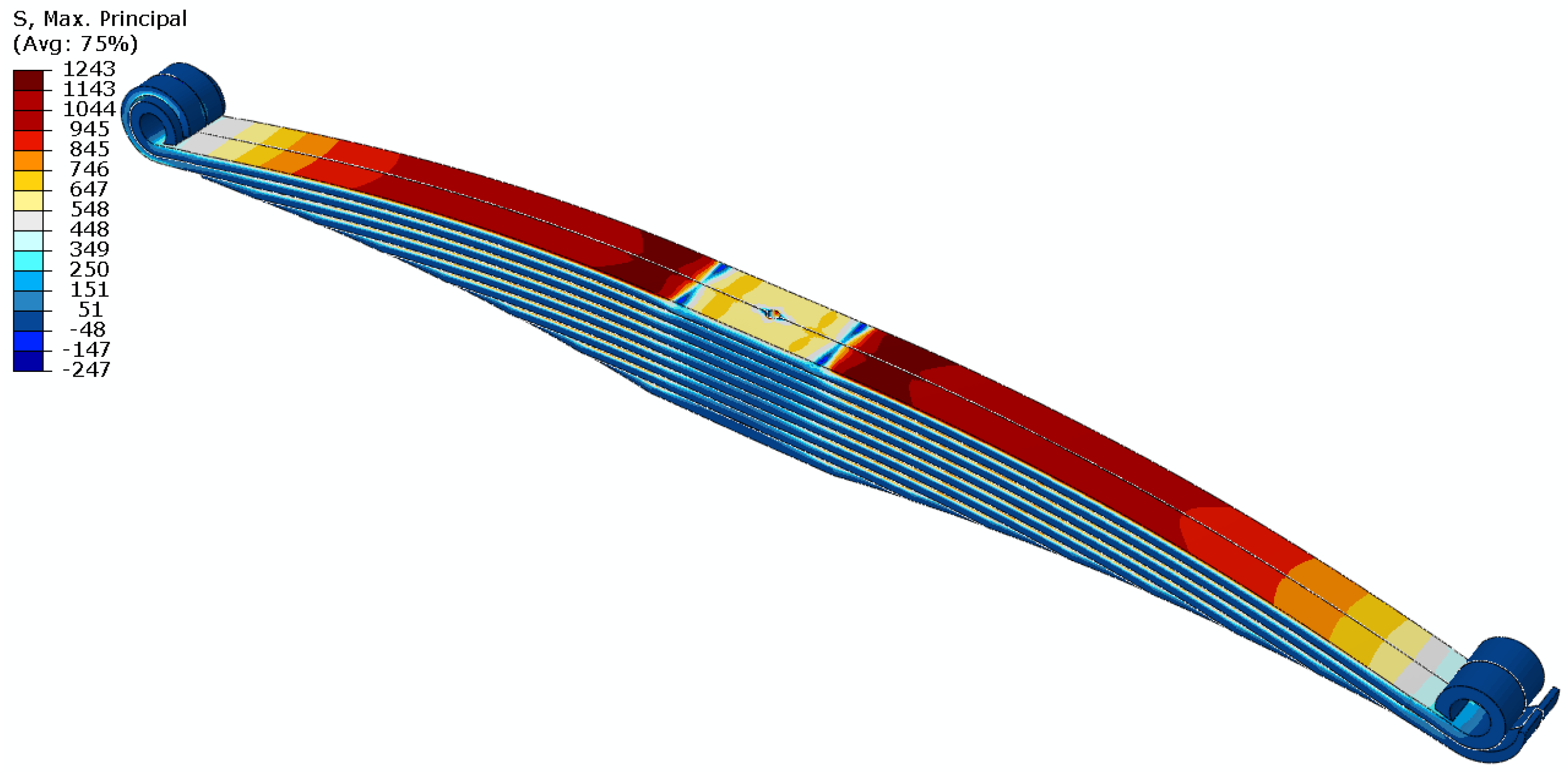

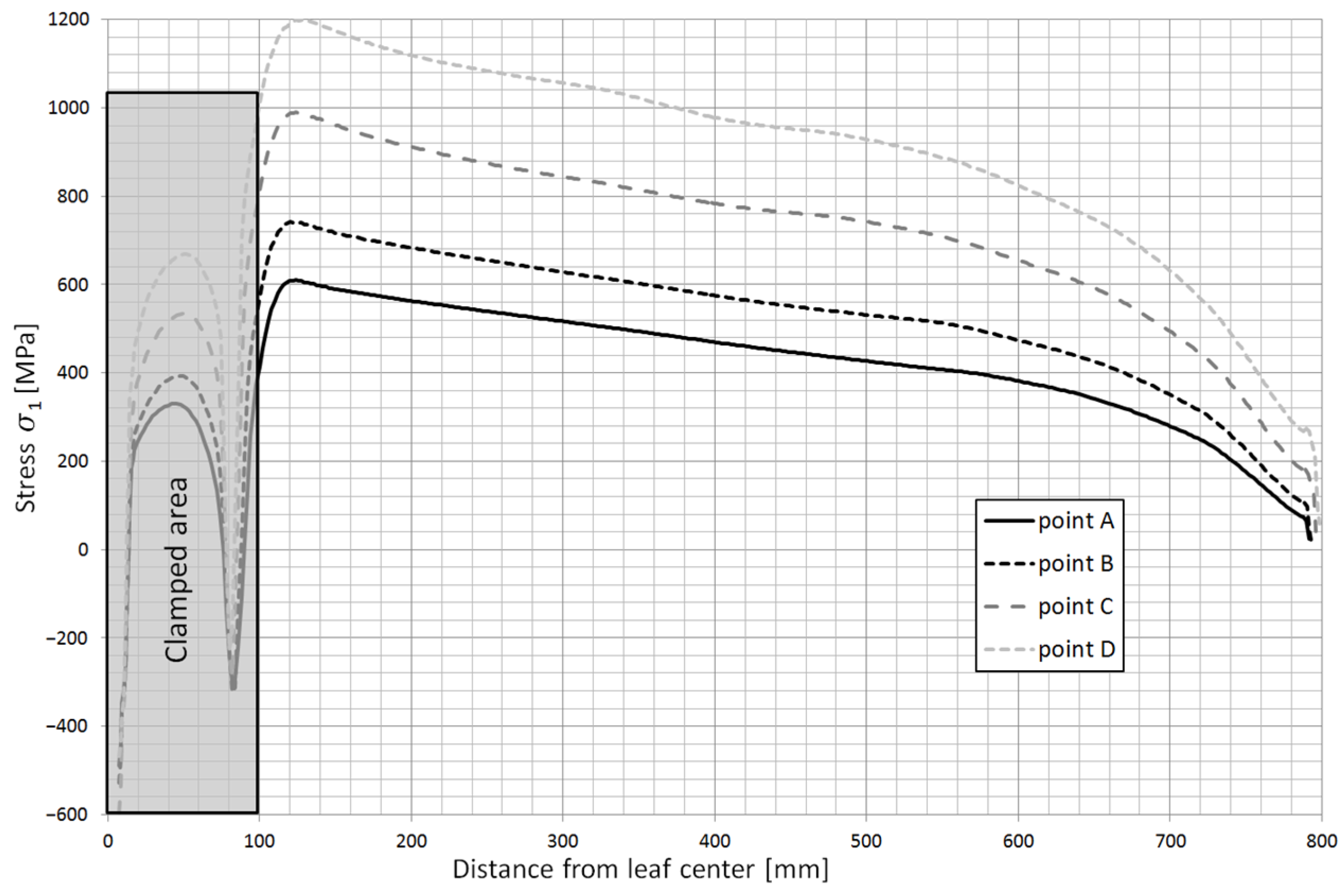

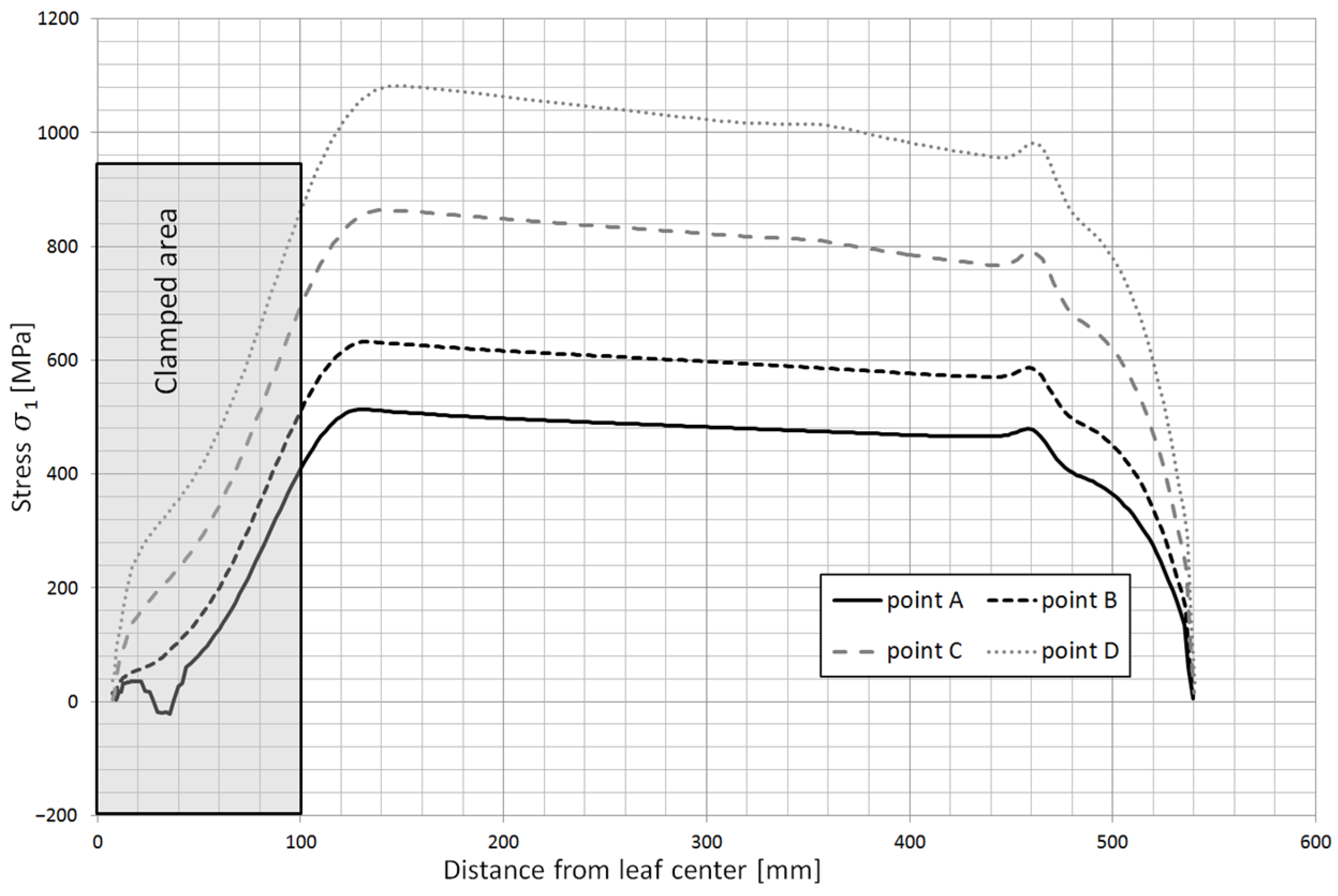

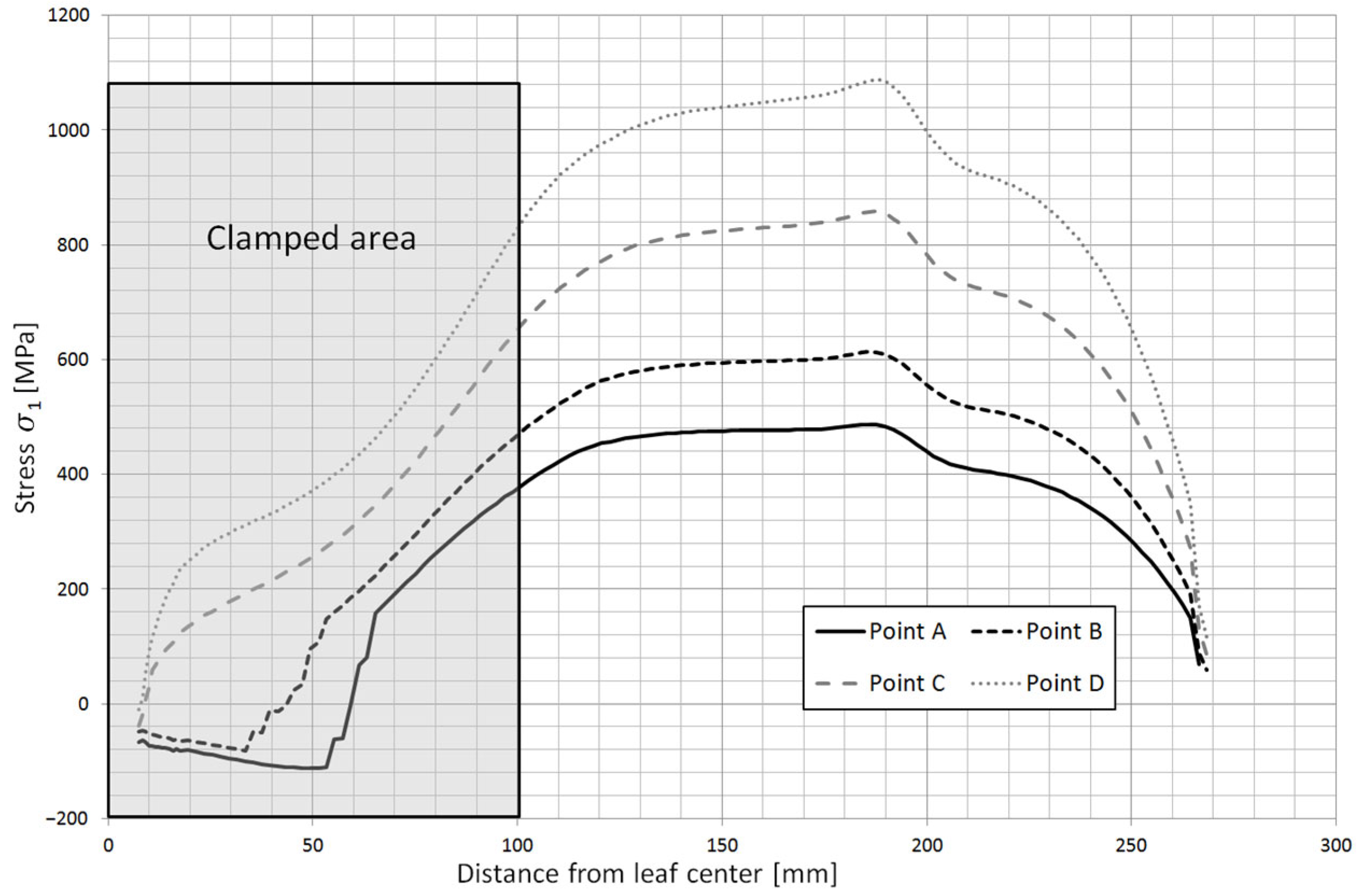

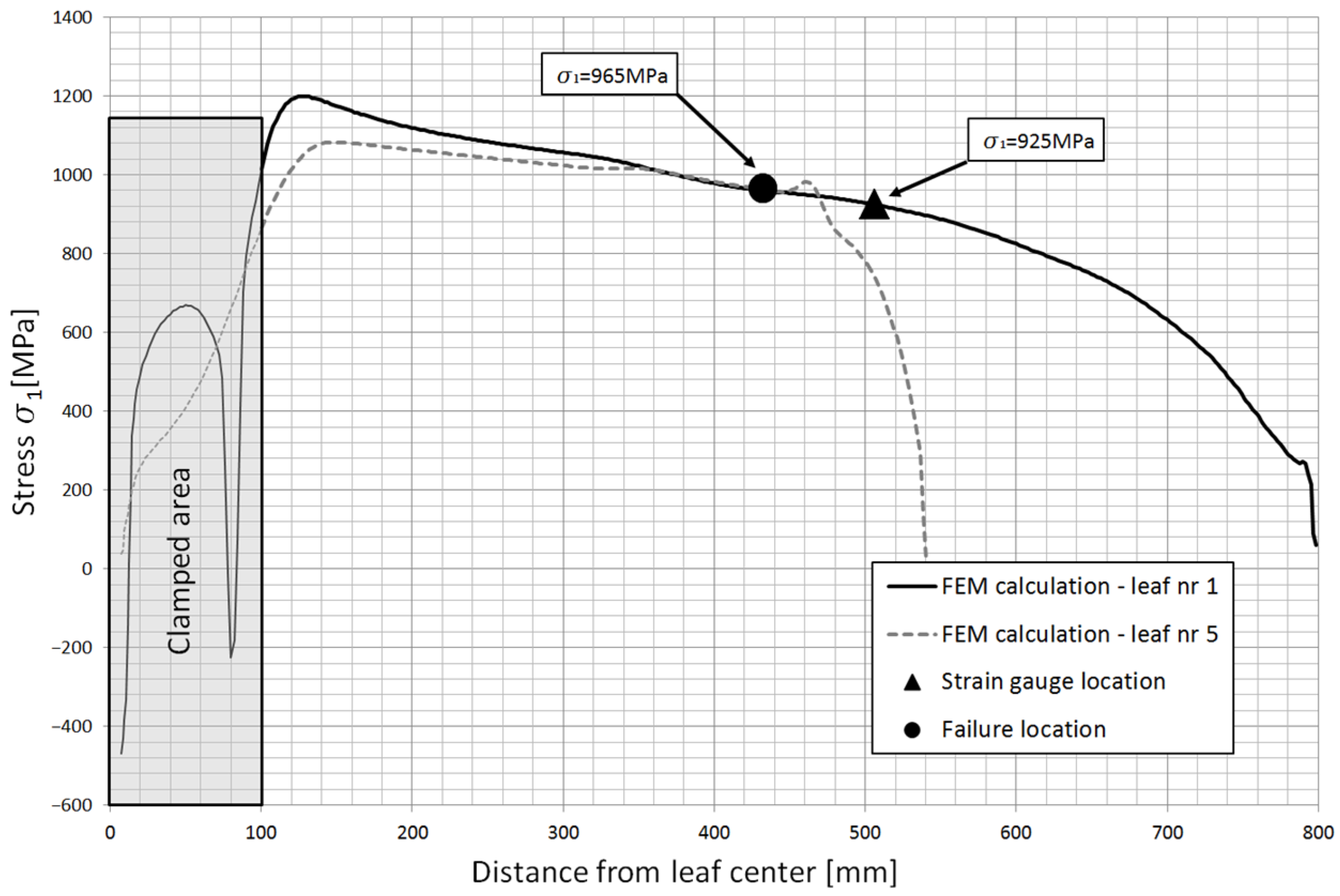

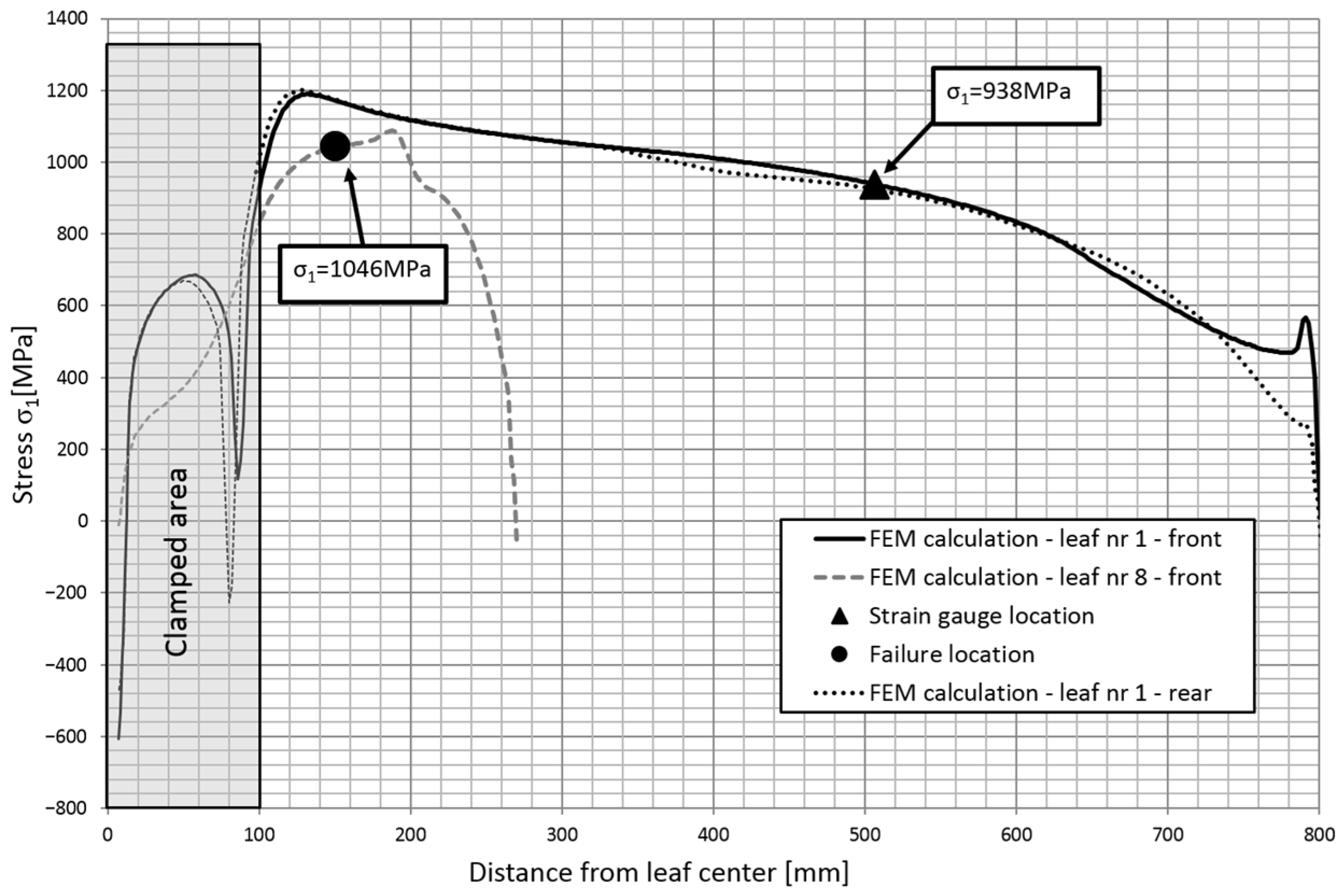

2.4. Numerical Analysis of Spring Geometry

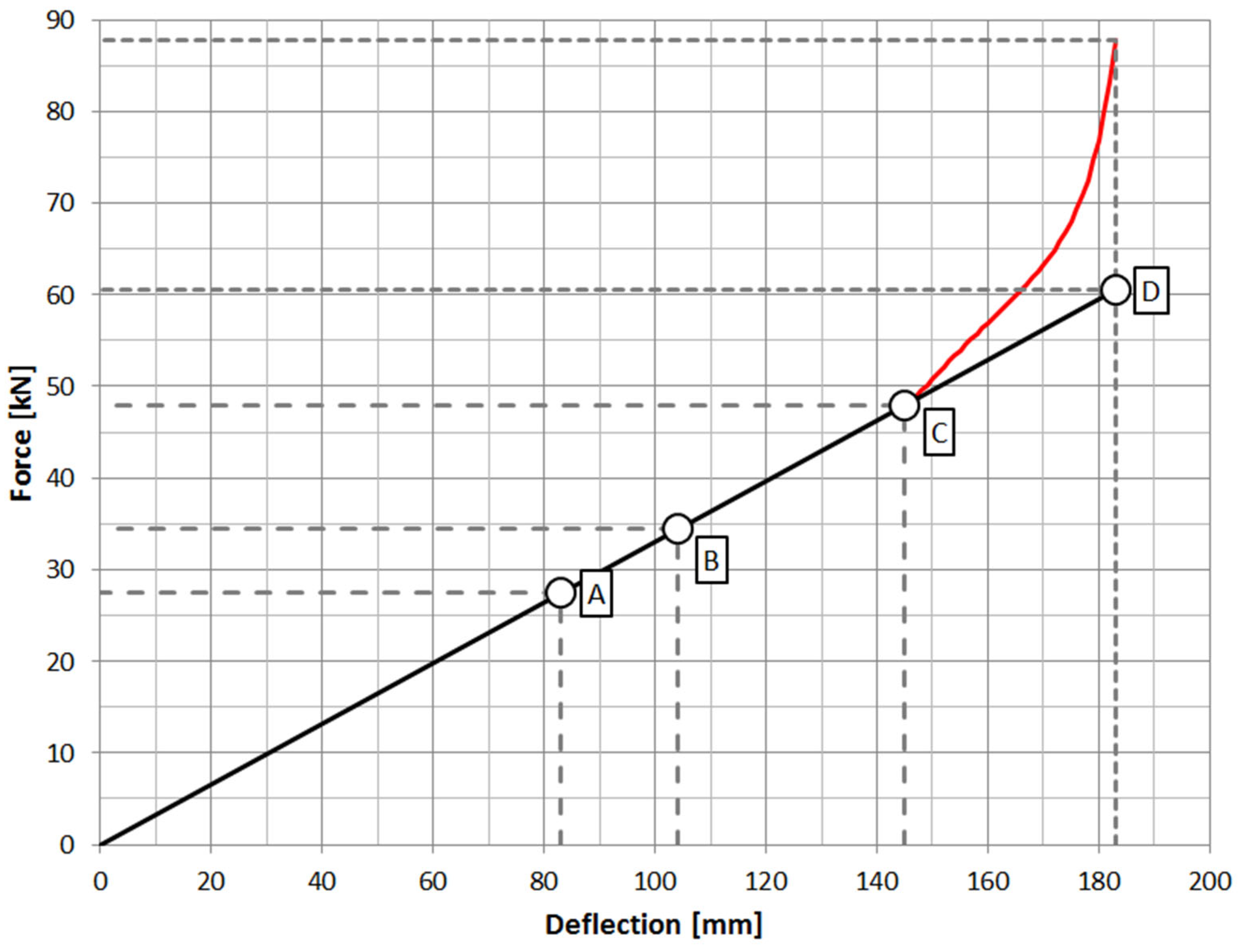

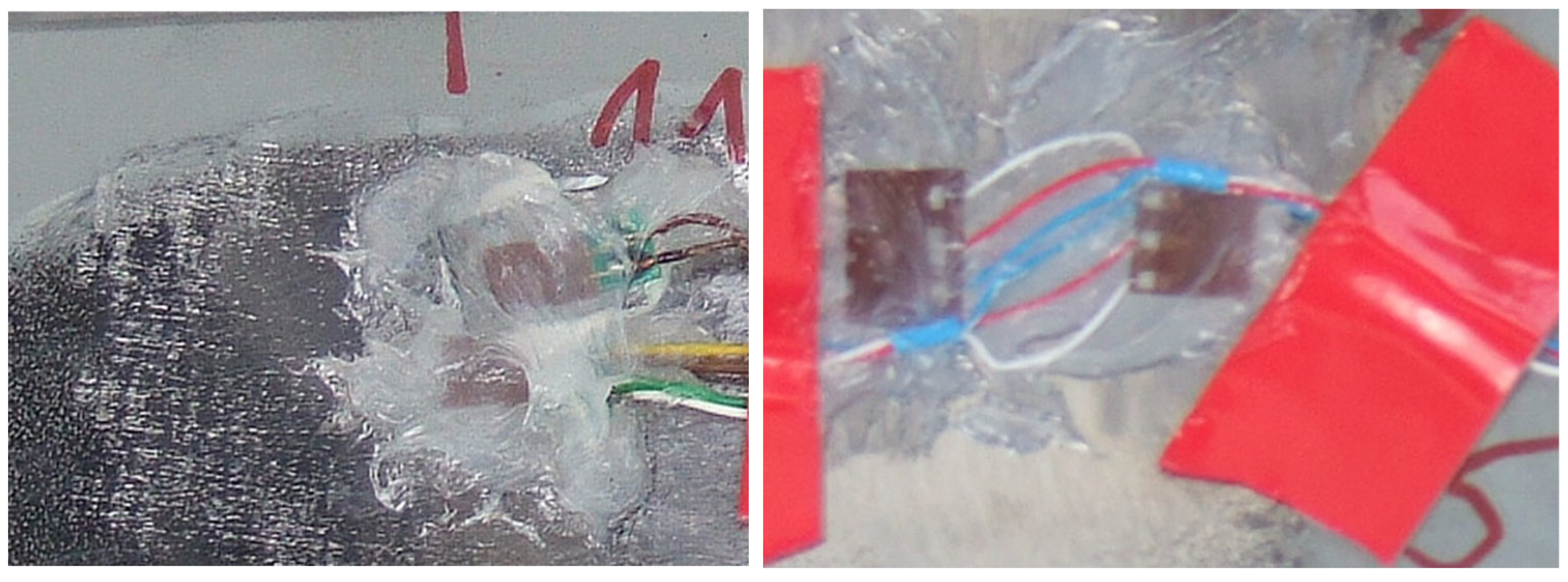

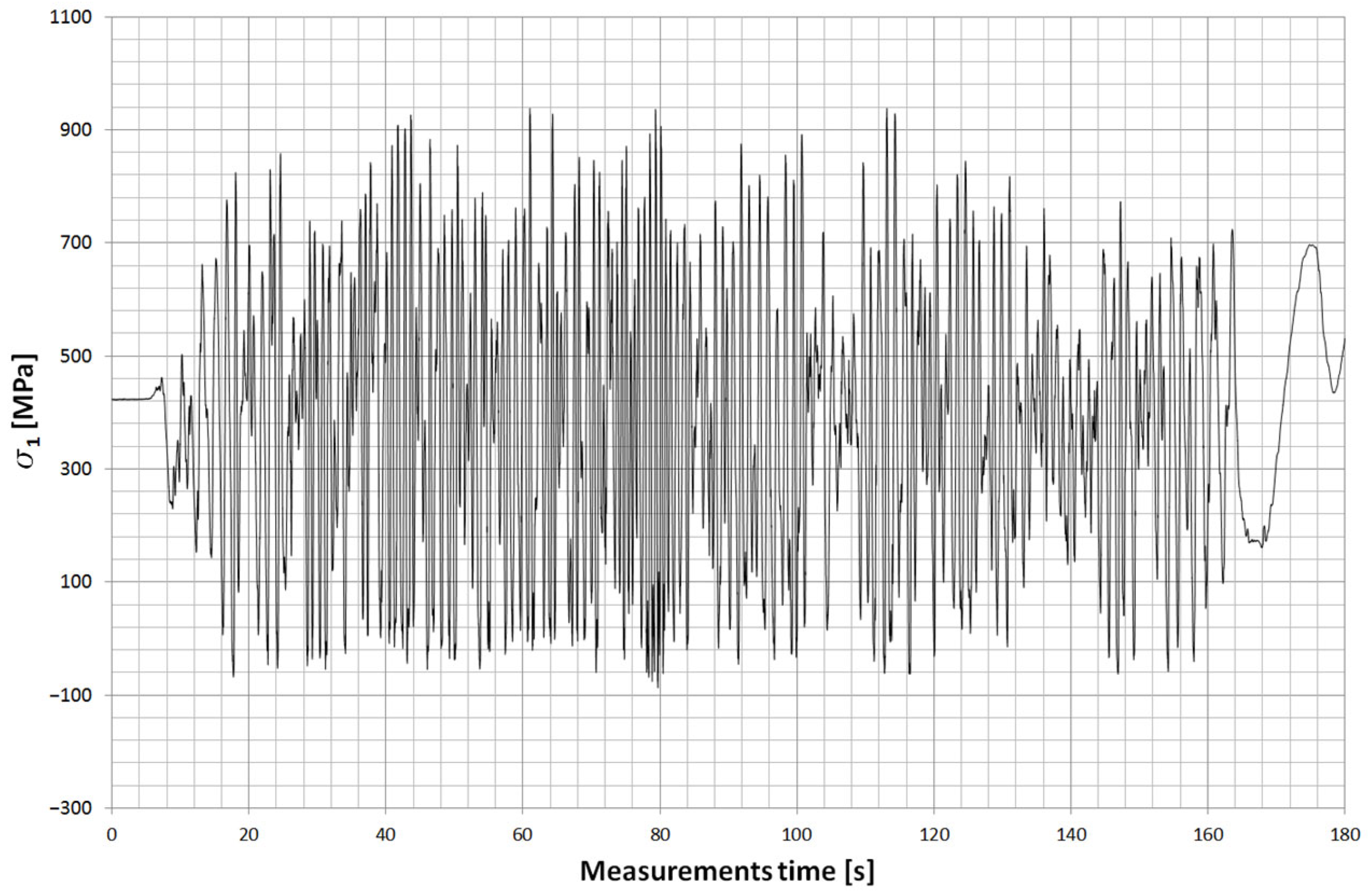

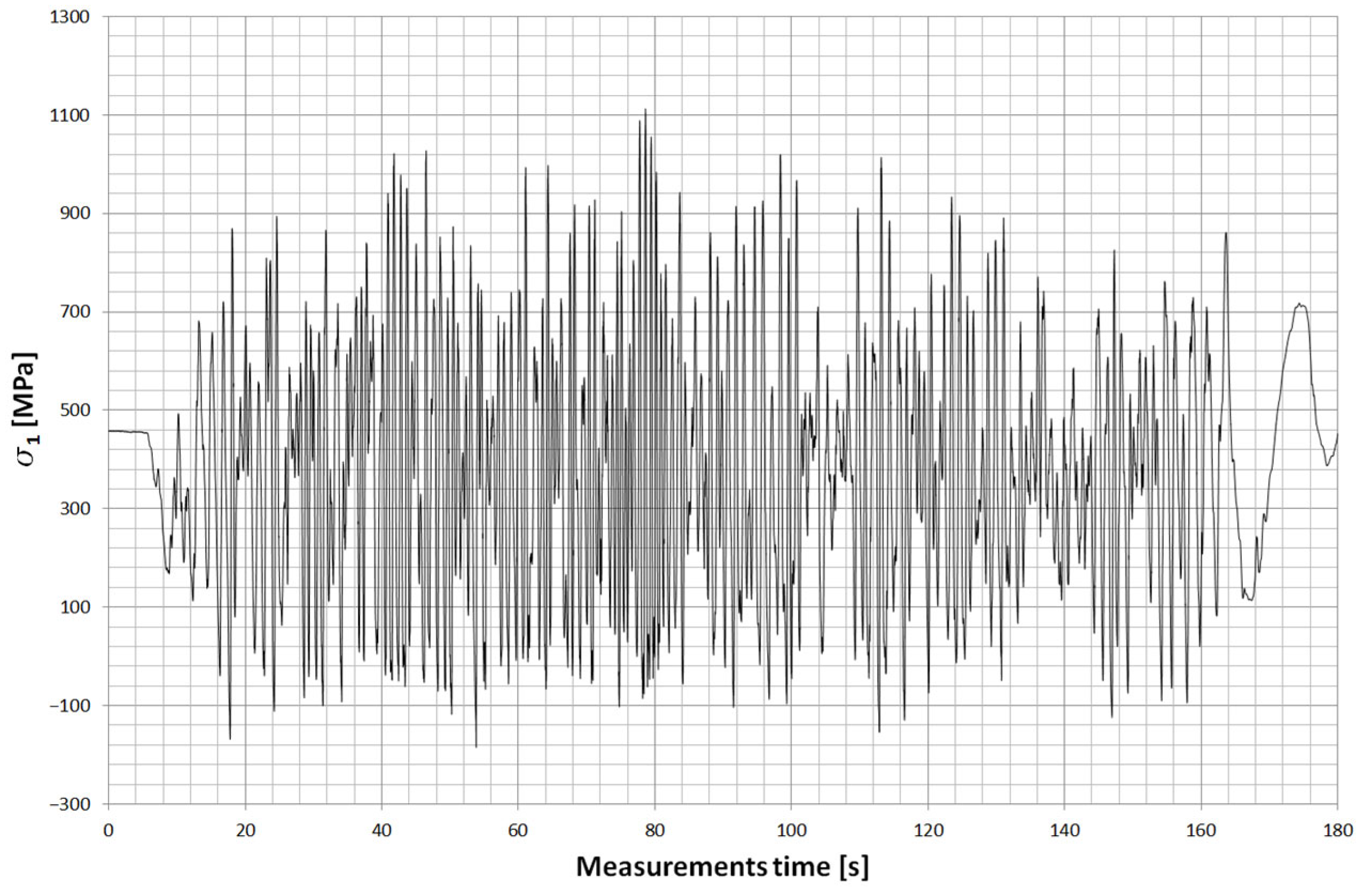

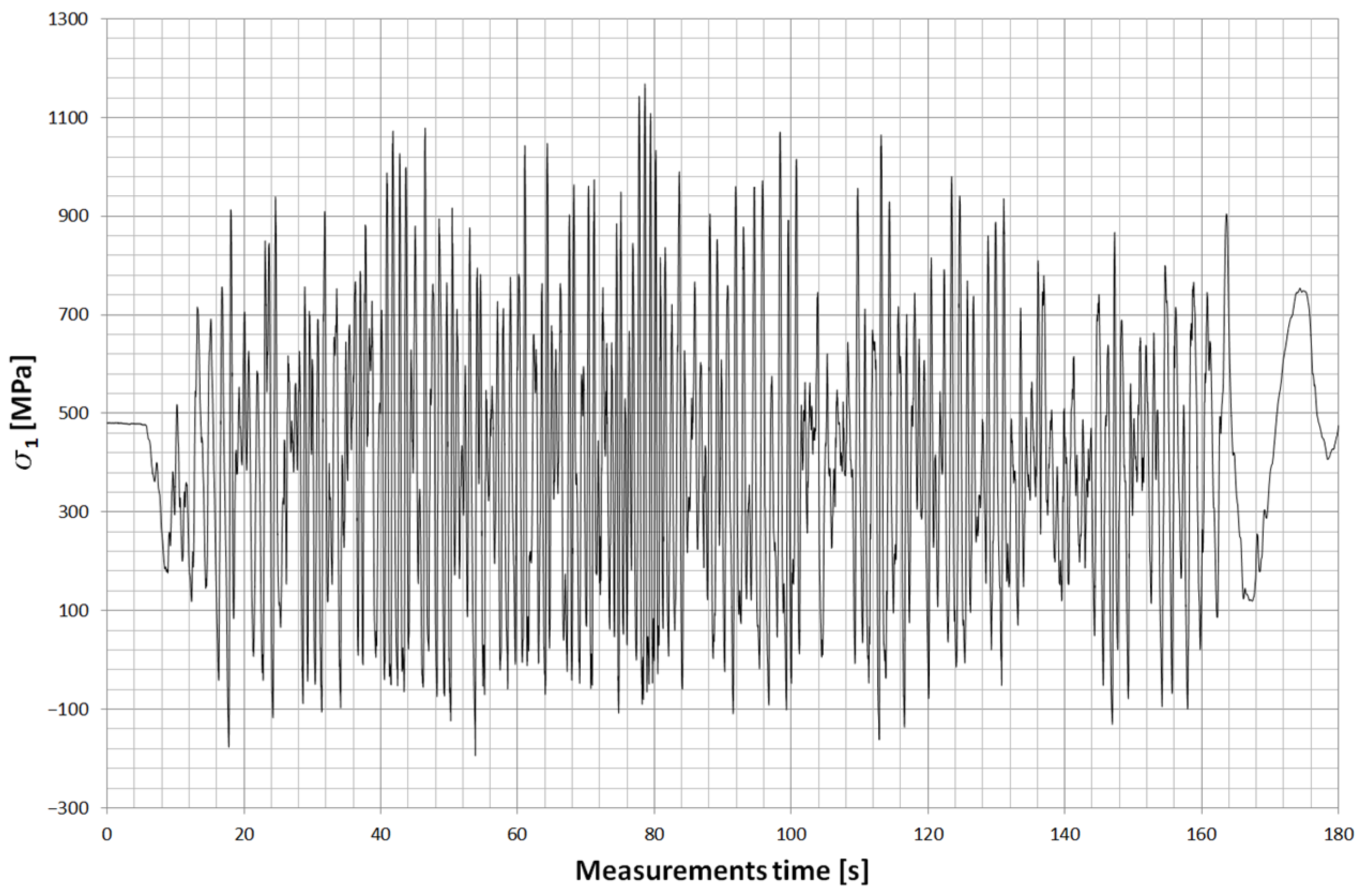

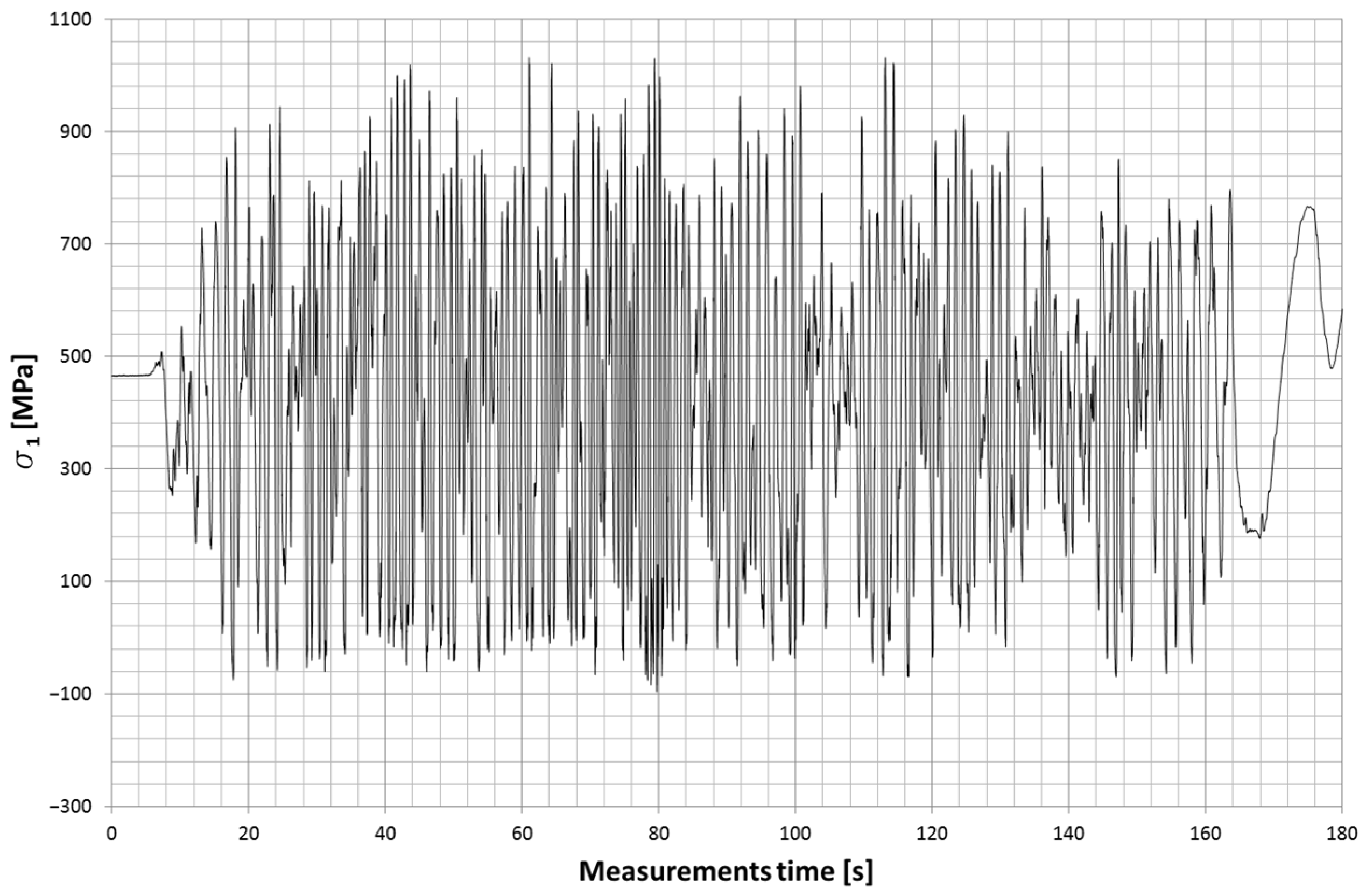

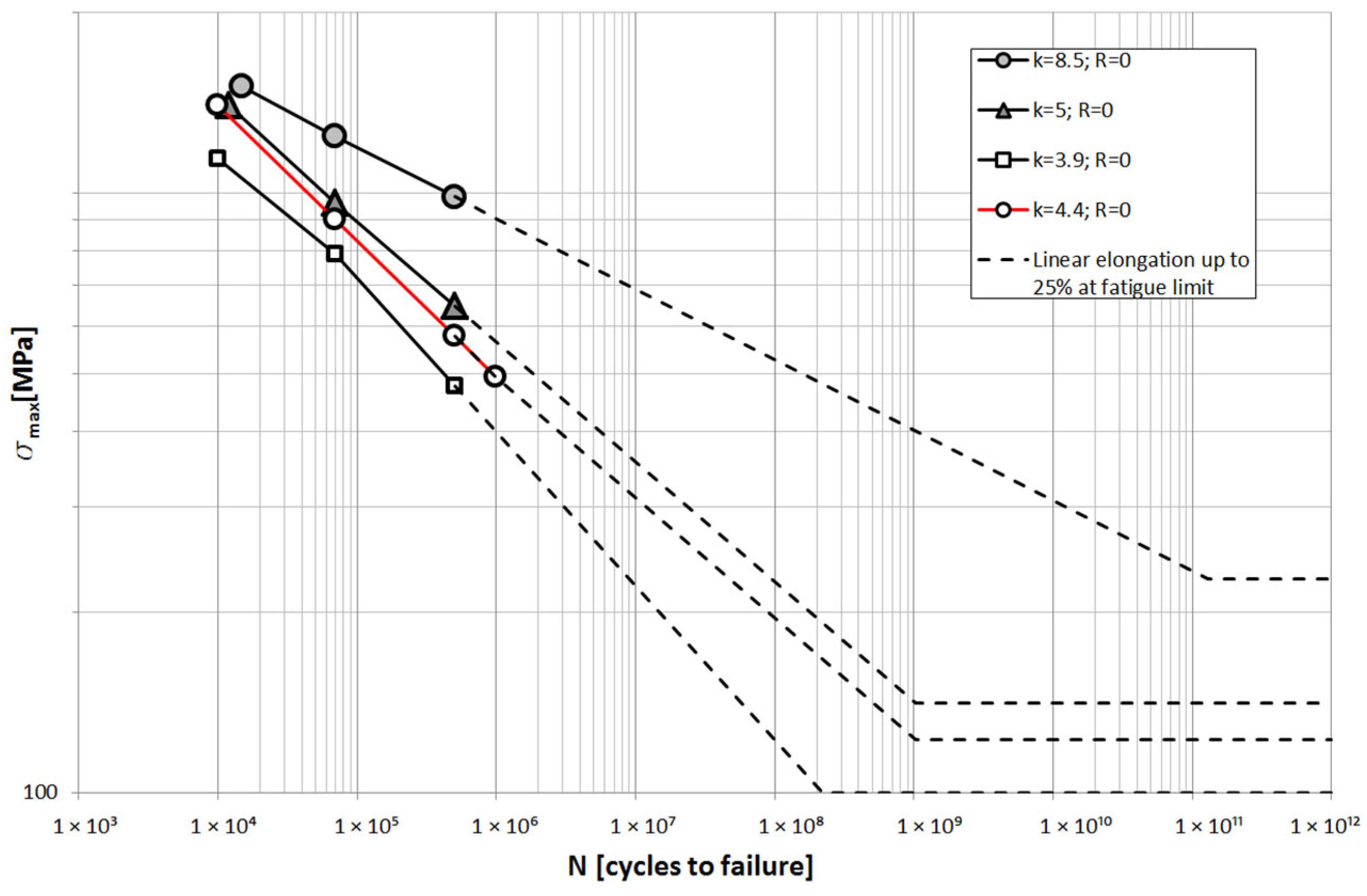

2.5. Experimental Tests

3. Summary and Conclusions

- Improperly matched spring to the operating load conditions of the car;

- Excessive strain on the spring during static loading—spring inflection;

- Inadequacy of heat treatment parameters to meet the temperature requirements for hardening and tempering of spring steels;

- Lack of properly executed finishing technology;

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ASTM E1926; Standard Practice for Computing International Roughness Index of Roads from Longitudinal Profile Measurements. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ISO 8608; Mechanical Mechanical vibration—Road surface profiles—Reporting of measured data. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Martínez-Hinojosa, R.; Garcia-Herrera, J.E.; Garduño, I.E.; Arcos-Gutiérrez, H.; Navarro-Rojero, M.G.; Mercado-Lemus, V.H.; Betancourt-Cantera, J.A. Optimization of Polymer Stake Geometry by FEA to Enhance the Retention Force of Automotive Door Panels. Adv. Eng. Lett. 2025, 4, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żak, S. Fatigue tests of heat-treated rails in the R350HT grade. Mater. Sci.-Pol. 2025, 43, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowicz, M.M. Insight into the microstructural stability and thermal fatigue behavior of nitrided layers on martensitic hot forging tools. Mater. Sci.-Pol. 2025, 43, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kader, E.E.; Abed, A.M.; Radojković, M.; Savić, S.; Milojević, S.; Stojanović, B. Design of a Copolymer-Reinforced Composite Material for Leaf Springs Inside the Elastic Suspension Systems of Light-Duty Trucks. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Shi, W.; Chen, Z.; Yang, S.; Song, Q. Fatigue reliability design of composite leaf springs based on ply scheme optimization. Compos. Struct. 2017, 168, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawryluk, M.; Marzec, J.; Lachowicz, M.; Makuła, P.; Nowak, K. Evaluation of the possibility of improving the durability of tools made of X153CrMoV12 steel used in the extrusion of a clay band in ceramic roof tile production. Mater. Sci.-Pol. 2023, 41, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Wu, Z.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, X. Effect of heat treatment and cooling rate on microstructure and properties of T92 welded joint. Mater. Sci.-Pol. 2023, 41, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civi, C.; Yurddaskal, M.; Atik, E.; Celik, E. Quenching and tempering of 51CrV4 (SAE-AISI 6150) steel via medium and low frequency induction. Mater./Mater. Test. 2018, 60, 614–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, C.K.; Borowski, G.E. Evaluation of a leaf spring failure. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2005, 5, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozd, K. Analiza możliwości wykazania przyczyn uszkodzeń piór resorowych. Eksploat. Niezawodn. 2003, 2, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Drozd, K. Fractographic and metallographic studies of vehicle suspension spring failures. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2011, 11, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Stańco, M.; Działak, P. Effect of the semi-elliptic spring mounting on its stiffness. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 32, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanco, M.; Działak, P.; Żędzianowski, B. Numerical and experimental analysis of the rubber bumper stiffness. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 12 Pt 2, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 10089:2005; Hot-Rolled Steels for Tempered Springs. Technical Terms of Delivery. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warszawa, Poland, 2005.

- DIN 4620; Spring Steel; Hot Rolled, with Rounded Edges for Leaf Springs; Dimensions, Tolerances, Masses, Sectional Properties. German Institute for Standardization: Berlin, Germany, 1992.

- PN-90/S-47250:1990; Motor Vehicles and Trailers. Leaf Springs Requirements and Tests. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warszawa, Poland, 1990.

- Sustarsic, B.; Borkovic, P.; Echlseder, W.; Gerstmayr, G.; Javidi, A.; Sencic, B. Fatigue strength and microstructural features of spring steel. Struct. Integr. Life 2011, 11, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hauserova, D.; Dlouhy, J.; Kotous, J. Structure reinfement of spring steel 51crv4 after accelerated spheroidisation. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2017, 3, 1473–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusiński, E.; Czmochowski, J.; Smolnicki, T. Zawansowana Metoda Elementów Skończonych; Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wrocławskiej: Wrocław, Poland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zienkiewicz, O.C.; Taylor, R.L. The Finite Element Method; McGraw-Hill Bool Company: London, UK, 1991; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Karditsas, S.; Savaidis, G.; Mihailidis, A. Leaf springs-Design, calculation and testing requirements. Mater. Test. 1999, 41, 234–240. [Google Scholar]

- Stańco, M.; Działak, P.; Hejduk, M. Failure Analysis of a Damaged U-Bolt Top Plate in a Leaf Spring. In Proceedings of the 14th International Scientific Conference: Computer Aided Engineering, CAE 2018, Wrocław, Poland, 20–23 June 2018; Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering. Rusinski, E., Pietrusiak, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kosobudzki, M. Preliminary Selection of Road Test Sections for High-Mobility Wheeled Vehicle Testing under Proving Ground Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosobudzki, M.; Zając, P.; Gardyński, L. A Model-Based Approach for Setting the Initial Angle of the Drive Axles in a 4 × 4 High Mobility Wheeled Vehicle. Energies 2023, 16, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosobudzki, M.; Stańco, M. The Experimental Identification of Torsional Angle on a Load-Carrying Truck Frame During static and Dynamic Tests. Eksploat. Niezawodn.-Maint. Reliab. 2016, 18, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragoudakis, R.; Saigal, A.; Savaidis, G.; Malikoutsakis, M.; Bazios, I.; Savaidis, A.; Pappas, G.; Karditsas, S. Fatigue assessment and failure analysis of shot-peened leaf springs. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2012, 36, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kömeç, A.; Dikçi, K.; Atapek, Ş.H.; Polat, Ş.; Çelik, G.A. Microstructural and mechanical characterization of the parabolic spring steel 51CrV4. Mater. Test. 2017, 59, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malikoutsakis, M.; Gakias, C.; Makris, I.; Kinzel, P.; Müller, E.; Pappa, M.; Michailidis, N.; Savaidis, G. On the effects of heat and surface treatment on the fatigue performance of high-strength leaf springs. MATEC Web Conf. 2021, 349, 04007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stańco, M.; Kowalczyk, M. Analysis of Experimental Results Regarding the Selection of Spring Elements in the Front Suspension of a Four-Axle Truck. Materials 2022, 15, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bathias, C.; Drouillac, L.; Le François, P. How and why the fatigue S–N curve does not approach a horizontal asymptote. Int. J. Fatigue 2001, 23 (Suppl. S1), 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonsino, C.M. Course of SN-curves especially in the high-cycle fatigue regime with regard to component design and safety. Int. J. Fatigue 2007, 29, 2246–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element Content [%] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | Si | Mn | Cr | V | Smax. | Pmax. |

| 0.47 ÷ 0.55 | ≤0.40 | 0.70 ÷ 1.10 | 0.90 ÷ 1.20 | 0.10 ÷ 0.25 | 0.025 | 0.025 |

| Rp0.2 min. [MPa] | Rm [MPa] | Amin. [%] | Zmin. [%] | Impact Strength at 20 °C Ku Min. [J] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1200 | 1350 ÷ 1650 | 6 | 30 | 8 |

| Hardening Temperature | Hardening Medium | Tempering Temperature |

|---|---|---|

| 850 ± 10 °C | oil | 450 ± 10 °C |

| No. | Hardening | Tempering | HV Hardness |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 [19] | 870 °C/10’ | 475 °C/1 h | 446 |

| 2 [20] | 860 °C/30’ | 450 °C/2 h | 434 |

| Sample no. 5 | - | - | 475 ± 11 |

| Sample no. 8 | - | - | 467 ± 9 |

| Guidelines of the standard | - | - | 382 ÷ 490 |

| Core Microhardness HV 0.1 | |

|---|---|

| leaf #5 | leaf #8 |

| 475 ± 11 | 467 ± 9 |

| m = 3.9 | m = 4.4 | m = 5 | m = 8.5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P5 Leaf | P8 Leaf | P5 Leaf | P8 Leaf | P5 Leaf | P8 Leaf | P5 Leaf | P8 Leaf | |

| Total number of cycles N [-] | 326,400 | 441,600 | 326,400 | 441,600 | 326,400 | 441,600 | 326,400 | 441,600 |

| Number of cycles considered for fatigue life estimation [-] | 165,600 | 172,800 | 153,600 | 158,400 | 144,000 | 154,400 | 114,400 | 124,000 |

| Degree of fatigue life depletion D [%] | 119 | 137 | 70 | 81 | 50 | 58 | 5 | 6 |

| Predicted number of kilometers until failure [km] | 841 | 728 | 1429 | 1235 | 1981 | 1713 | 18,523 | 16,498 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stańco, M.; Kaszuba, M.; Herbik, I. Identification of Factors Leading to Damage of Semi-Elliptical Leaf Springs. Materials 2025, 18, 5426. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235426

Stańco M, Kaszuba M, Herbik I. Identification of Factors Leading to Damage of Semi-Elliptical Leaf Springs. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5426. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235426

Chicago/Turabian StyleStańco, Mariusz, Marcin Kaszuba, and Iwona Herbik. 2025. "Identification of Factors Leading to Damage of Semi-Elliptical Leaf Springs" Materials 18, no. 23: 5426. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235426

APA StyleStańco, M., Kaszuba, M., & Herbik, I. (2025). Identification of Factors Leading to Damage of Semi-Elliptical Leaf Springs. Materials, 18(23), 5426. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235426